Abstract

One-dimensional SnO2- and Li+-doped SnO2 porous nanofibers were easily fabricated via electrospinning and a subsequent calcination procedure for ultrafast humidity sensing. Different Li dopant concentrations were introduced to investigate the dopant’s role in sensing performance. The response properties were studied under different relative humidity levels by both statistic and dynamic tests. The best response was obtained with respect to the optimal doping of Li+ into SnO2 porous nanofibers with a maximum 15 times higher response than that of pristine SnO2 porous nanofibers, at a relative humidity level of 85%. Most importantly, the ultrafast response and recovery time within 1 s was also obtained with the 1.0 wt % doping of Li+ into SnO2 porous nanofibers at 5 V and at room temperature, benefiting from the co-contributions of Li-doping and the one-dimensional porous structure. This work provides an effective method of developing ultrafast sensors for practical applications—especially fast breathing sensors.

Keywords: humidity sensor, electrospun porous nanofibers, lithium doping, response-recovery behavior

1. Introduction

Humidity sensors are of great importance in many fields, including environmental monitoring, industrial production, agricultural planting, aviation, and medical and chemical monitoring [1,2,3]. Until now, various transduction techniques have been used to develop humidity sensors, such as capacitance [4], impedance [5], optical fiber [6,7], and surface acoustic wave (SAW) [8]. Nanostructured metal oxides are ideal materials for the fabrication of humidity sensors because of the ability to tailor their surface and charge-transport properties, as well as their chemical and physical stability and high mechanical strength [9,10,11]. Remarkably, as one of the most important typical n-type metal oxide semiconductors, SnO2 materials have attracted much attention as chemical sensing materials but have suffered from the obvious drawbacks of low conductivity, long response/recovery time, and narrow measuring range [8,12,13]. Especially, the slow response and recovery speed hindered the applications of SnO2-structured materials as humidity sensors.

The response of SnO2-based humidity sensors depends upon reactions between water molecules and SnO2 surfaces, which have stimulated the interest of researchers in tailoring the microstructure and morphology of SnO2 nanostructures [14,15]. One-dimensional (1D) nanostructures, such as nanowires, nanorods, and nanobelts, have attracted much attention, since, benefiting from their geometric advantages, they can make aimed molecule access easy and provide excellent electron transport and efficient response and recovery properties, [13,16,17,18]. Wang et al. synthesized high-yield SnO2 nanowires that demonstrate very high response performances on humidity sensing and a short reaction speed [16]. One-dimensional SnO2/TiO2 heterostructures were also successfully synthesized through the hydrothermal assembly of single-crystalline SnO2 nanocubes on TiO2 electrospun nanofibers, where the response and recovery times could reach ~2.4 s and ~30.2 s, respectively [19]. The SnO2 nanowire networks made from 1-D nanostructures were synthesized by a simple and versatile flame transport synthesis approach, exhibiting promising sensing performances [14]. Additionally, another approach for enhancing the sensing properties of SnO2 lies in its modification with metal nanoparticles, such as Ag, Fe, and Cu [20,21,22]. M. Sabarilakshmi synthesized W-doping SnO2 nanopowders and found that W-doping improves sensitivity along with a better response (38 s) and recovery time (25 s) toward open air at room temperature, leading to the synergic electronic interactions between the dispersed W and the characteristic formation of the SnO2 nanoparticles [23]. Ag-SnO2/SBA-15 also exhibited ultrahigh sensitivity over the entire RH range, along with rapid response (5 s) and recovery times (8 s), relatively low hysteresis (0.9%), and excellent stability (1.1%) in the 11%–98% RH range [24]. However, up to now, the response and recovery times of the reported sensors, even based on the nanostructured materials, are usually beyond 5 s (the time should be no more than 5 s in fast breathing sensors), which hinders ultrafast sensing applications [15].

In our work, in order to achieve the ultrafast humidity sensors, we provided a combined strategy of structured construction and doping. The main focus in our work was directed toward the design of a novel additive and structure of 1D nanostructured SnO2 that can increase and activate the interaction between sensing materials and moisture surroundings. Li+-doped SnO2 porous nanofibers (PNFs) were developed as a high-efficiency and ultrafast humidity sensor via electrospinning for the very first time. Excellent humidity sensing properties such as high sensitivity, especially fast response-recovery behavior (within 1 s), were achieved with the Li+-doped SnO2 1D porous nanofibers. We thus offer here an effective approach toward an understanding, and the design, of SnO2-based humidity sensing materials.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Morphological and Structural Characteristics

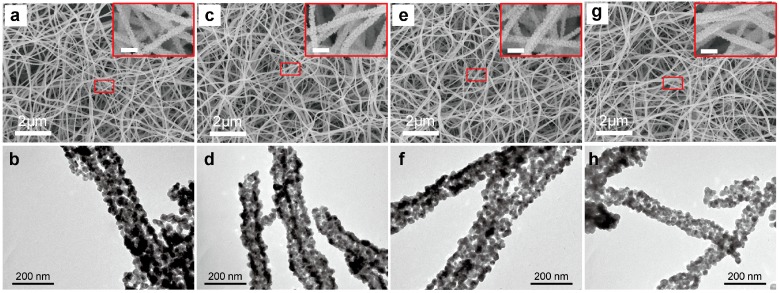

A scanning electron microscope and transmission electron microscope were used to characterize the morphologies of pristine SnO2 and Li+-doped SnO2 PNFs with different amounts of Li+ by electrospinning and post-calcination at 600 °C, as shown in Figure 1. All the as-prepared pristine SnO2 and the doped SnO2 display a uniform fiber-like structure. Simultaneously, the PVP will be removed with the post-calcination procedure, which results in the formation of high porosity and bended fibrous morphologies. The average diameters of the final nanofibers range from 80 to 100 nm, and the small nanocrystals composing these nanofibers are 10–20 nm. The large voids between the adjacent fibers and small pores within the final fibers will provide an easy pathway for water molecules to penetrate easily into the whole membranes, benefiting the humidity sensing properties. It can be concluded that SnO2 with a porous fiber-like morphology was successfully synthesized in this study via a simple electrospinning technique.

Figure 1.

Scanning electron microscope images (a,c,e,g) and transmission electron microscope images (b,d,f,h) images of (a,b) pristine SnO2 porous nanofibers as well as (c,d) 1.0 wt %, (e,f) 4.0 wt %, (g,h) 8.0 wt % Li+-doped SnO2 porous nanofibers prepared by electrospinning and post-calcination at 600 °C in air for 5 h. The insets are high-resolution SEM images (Scale bar: 200 nm). The pristine SnO2 porous nanofibers and Li+-doped SnO2 porous nanofibers showed a porous structure. The Li+-doped SnO2 porous nanofibers can be controlled by changing the ratio of lithium chloride hydrate in precursors.

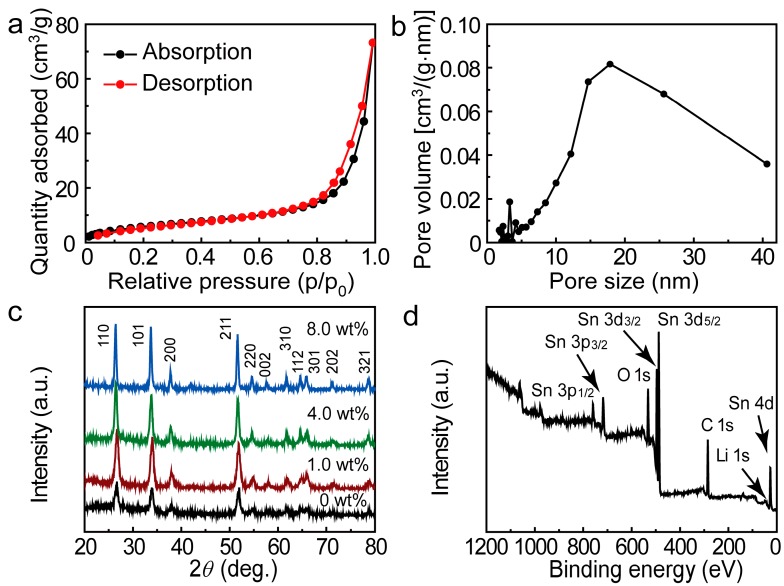

The porosity of the as-prepared porous nanofibers was then studied by nitrogen adsorption and desorption isotherms (ASAP 2020 HD88, Micromertitics instruments, Norcross, GA, USA). Based on the Barret-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) method and the adsorption branch of the nitrogen isotherm, the calculated pore size distribution indicates two correspondingly pore size distribution centers at about 3.2 nm and 17.9 nm. The BET surface area of the as-prepared nanofibers is calculated to be 22.53 m2/g (shown as Figure 2a,b). Figure 2c shows the XRD patterns of the as-prepared SnO2 PNFs with different Li doping levels. All of them display clear reflections from (110), (101), (200), (111), (210), (211), and (220) crystallographic planes of the rutile structure SnO2 crystalline phase (JCPDS 41-1445) [14,25]. No phase ascribed to Li oxides can be seen, indicating the possible entrance of Li into tin oxide lattice, which can be deduced from the lattice change of SnO2. As the Li dopant increases, the diffraction peaks of SnO2 were found to shift left, indicating the increased lattice constant by Li doping. To confirm the existence of Li in the Li+-doped SnO2 PNFs, an XPS spectrum was used to investigate the composition of the doping sample (shown in Figure 2d), which confirm the presence of Li 1s (~55.0 eV) [26] in the doping sample, as well as the presence of Sn 4d, Sn 3d3/2, Sn 3d5/2, Sn 3p1/2, Sn 3p3/2, C 1s, and O 1s [27].

Figure 2.

(a) Nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherms; (b) DFT pore-size distribution plot of 1.0 wt % Li+-doped SnO2 porous nanofibers; (c) XRD patterns of pristine and Li+-doped SnO2 porous nanofibers; (d) XPS full spectrum of 1.0 wt % Li+-doped SnO2 porous nanofibers, which confirmed the presence of Li 1s (~55.0 eV) in the doping sample.

2.2. Humidity Sensing Properties

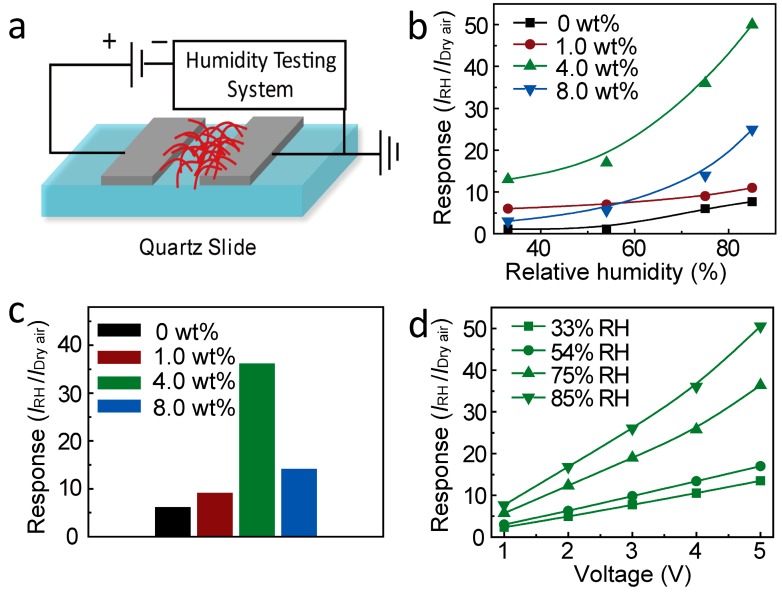

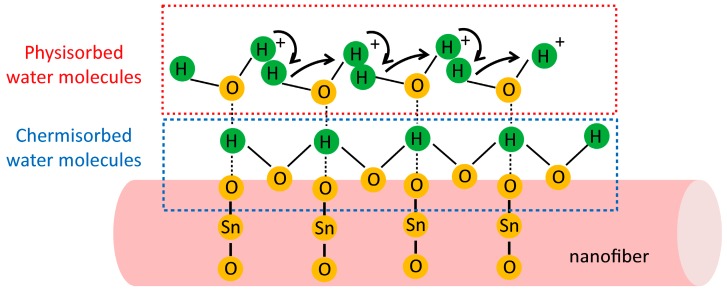

The SnO2-based humidity sensor was then constructed by depositing a pair of Al electrodes, as illustrated in Figure 3a. The response of SnO2 PNF-based sensors at different humidity levels is defined as the ratio of the measured currents at selected RH value and that under dry air. In other words, it can be estimated as S = IRH/Idry air [28], where the IRH is the current of the sensor at the selected humidity level, and Idry air is the current of the sensor at dry air condition. Figure 3b shows the response properties of different doping levels of Li+-doped SnO2 PNFs under different RH values. For the pristine SnO2 PNFs, the responses are 1.1, 1.2, 7.2, and 10.0 at the 33%, 54%, 75%, and 85% RH, respectively. The relatively low response, especially under low RH, e.g., 33% and 54%, is limited mainly by a poor adsorption ability of water molecules. Obviously, the water concentration in air has a strong influence on the humidity response of SnO2. The basic humidity sensing mechanism on the SnO2 is explained by the sorption of water molecules onto the surface, which is usually described by the condensation of water molecules onto the sensor surface, inducing the proton conduction and consequently causing a change in the net conductivity of the sensor [29]. At a relatively low RH value, the chemisorption occurs to form two surface hydroxyls per water molecule [30]. With increasing humidity levels, the physisorption of water molecules takes place, resulting in capillary condensation and conduction by the Grotthuss transport mechanism [31], further enhancing the humidity sensing properties. Therefore, humidity sensing was detected as increasing with the increasing RH value. The schematic representation of SnO2 PNFs on the humidity sensing performance is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

(a) Schematic illustration of the SnO2 porous nanofiber-based sensor; (b) the response vs. the relative humidity (RH) of different doping levels of Li+-doped SnO2 porous nanofibers at 5 V under room temperature; (c) the response comparison of different Li+-doped SnO2 porous nanofibers under 75% relative humidity; (d) the response sensitivity–driving voltage properties for 4.0 wt % Li+-doped SnO2 porous nanofiber sensors under various relative humidity levels.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation or the benefit of the one-dimensional characteristic structure of SnO2 porous nanofibers on humidity sensing performance.

As Li+ was introduced to SnO2, the response sensitivity was obviously increased, which can be inferred from the curves in Figure 3b. A response comparison of different Li+-doped SnO2 PNFs under 75% RH value can be made based on Figure 3c, which clearly indicates the volcano-shape of the response with the Li doping content. The humidity response first increased as the Li+ doping content increased from 1.0 to 4.0 wt %, and then decreased as the Li+ doping content continued increasing to 8.0 wt %. The 4.0 wt % doped SnO2 showed the best response sensitivity, with values of 13.4, 17.0, 36.3, and 50.5 at 33%, 54%, 75%, and 85% RH, respectively, which is 5 times higher than that of the pristine SnO2 PNFs at high RH values of 75% and 85%, and around 15 times higher than that of the pristine PNFs at low RH values of 33% and 54%.

The enhanced response can be mainly attributed to the alkaline Li+ bonding interface to create a strong adhesion to water molecules, which can effectively induce a current change [32]. The similar enhanced sensing performance was also reported for Li+-TiO2 nanofibers, which were demonstrated to act as a highly sensitive humidity sensor [17]. In our Li-SnO2 system, the responses of doped sensing nanofibers could be enhanced, even at low RH levels, also proving the important tuning ability of water molecular adsorption of Li doping on SnO2. However, the Li doping has optimal content. As the doping level increased to 8.0 wt %, worse performance was unfortunately detected, which may be attributed to the excess of the conduction carriers (Li+ ions) resulting in an increased value of Idry air and the consequently a declined response value (IRH/Idry air). However, the humidity response is still higher than that of the pristine SnO2 PNFs. Figure 3d shows the response-driving voltage properties of the 4.0 wt % Li+-doped SnO2 PNFs sensor under various relative humidity levels. The linear behavior of the humidity response with driving voltage suggests optimum ohmic contact between SnO2 and the Al electrodes. The humidity sensing responses for all sensors increased as the RH value increased, indicating that water vapor has a strong influence on conductivity.

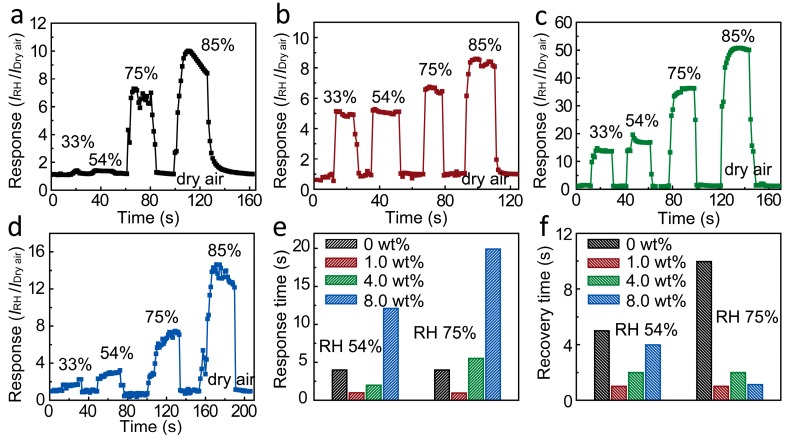

The dynamic tests were also characterized to show the water vapor influence on the conductivity of SnO2 NWs, as shown in Figure 5a–d. It was found that a conductivity change resulting from the fluctuation of RH is always reversible. When the sensor was exposed to the moist air in reference to dry air, the current promptly increased through the SnO2 and then gradually reached a relatively stable value. When the sensor was switched to dry air again, the current abruptly decreased and rapidly reached a relatively stable value. The responses of all sensor materials gradually increased as the RH value increased from 33 to 85%. The results coincided with the response results in Figure 3. The response and recovery behavior is the important characteristics for evaluating the performance of humidity sensors. Figure 5e,f illustrate the response time and recovery time (defined as the time required to reach 90% of the final equilibrium value) comparison under 54% and 75% RH values for different Li+-doped SnO2 PNFs, respectively. The response time of the SnO2 PNFs is ~4 s under both 54% and 75% RH. As Li was doped to SnO2, the 1.0 wt % Li+-doped SnO2 PNFs showed a response time of as low as 1 s under both 54% and 75% RH, much faster than that of 4 s on the pristine SnO2 PNFs. The 4.0 wt % Li+-doped SnO2 PNFs also showed the low response time of ~2 s under a 54% RH value. The recovery time is also an important characteristic for the ultrafast humidity sensor. The recovery time of SnO2 PNFs is ~5 s under 54% RH and 10 s under 75% RH. The fast recovery time of 1 s was found on the 1.0 wt % Li+-doped SnO2 PNFs under both 54% and 75% RH. The 4.0 wt % Li+-doped SnO2 PNFs also show the fast recovery time of 2 s under both 54% and 75% RH. The Li+-doped SnO2 PNFs show a recovery time lower than that of the pristine SnO2 PNFs. The ultrafast response/recovery speed (within 1 s) of 1.0 wt % Li+-doped SnO2 nanospheres enables its novel application as a human breathing sensor because human breathing intervals are within 5 s.

Figure 5.

The response and recovery properties at DC 5 V with an Li doping level of (a) 0, (b) 1.0, (c) 4.0, and (d) 8.0 wt %, respectively, at different relative humidity values; The comparison of (e) the response time and (f) the recovery time of different Li+-doped SnO2 PNFs at relative humidity levels of 54% and 75%, respectively.

The enhanced response, the ultrafast response, and the recovery speed of 1 s could be attributed to the co-contribution of the doping of Li+ ions and the 1D characteristic structure of PNFs. The alkaline Li+ bonding interface altered the surface correlation with water molecules, which subsequently vary the response and recovery behavior of Li+-doped SnO2. There is a suitable doping content. Furthermore, the characteristic structure of 1D PNFs has a large surface-to-volume ratio, which makes the absorption of water molecules on the surface of the sensors easy. The 1D nanoporous structure of the fibers can facilitate the aggregation of water molecules and fast mass transfer of the water molecules to and from the interaction region and can improve the rate for charge carriers in PNFs to transverse the barriers induced by molecular recognition along the fibers.

3. Materials and Methods

Chemicals were purchased from Aladdin Industrial (Shanghai, China) and used as received without any further purification. Exactly 5.0 wt % of tin (II) chloride dihydrate was dissolved in 40 wt % of N’,N’-dimethylformamide (DMF) and 45 wt % of ethanol under vigorous stirring for 10 min. Subsequently, 10 wt % of poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) (PVP, Mw = 1,300,000, Sigma-Aldrich, Shanghai, China) and a suitable amount of lithium chloride hydrate was added into the above solution under vigorous stirring for 30 min. The mixture was loaded into a glass syringe with a needle of 1 mm in diameter at the tip and was electrified using a high-voltage direct current (DC) supply. Fifteen kilovolts were provided between the tip of the spinning nozzle and the collector at a distance of 20 cm. Finally, the nanofiber mats were peeled off from the collector and placed in a crucible. Calcination (600 °C in air for 5 h) was performed to remove PVP, and get crystallized SnO2. The pristine SnO2 PNFs were also obtained with a free addition of lithium chloride hydrate by the same procedure.

Most of humidity sensors are investigated in alternating current (AC) conditions by evaluating the impedance change, which can avoid the polarization effects of absorbed water. However, the corresponding signal processing circuits are complicated. In our work, the direct current humidity sensors were fabricated as follows. The pristine and Li+-doped SnO2 PNFs were separately mixed with deionized water (5:100 by weight) to form a paste, and the paste was then dipcoated onto an 1 cm × 1 cm quartz substrate with a pair of Al electrodes (a length of 2 mm and a gap width of 100 μm). The conductivity of the PNFs was measured using a programmable DC voltage/current generator (Keithley 4200, Tektronix, Inc., Beaverton, OR, USA). The different relative humidity levels were controlled by salt solutions. Two chambers were used in our experiment, and the quick response sensors were measured by switching sensors between the two chambers [17,28,33,34]. Each chamber was stabilized at 25 °C for 12 h to ensure that the air in the chamber reached the equilibrate state, with a standard humidity sensor to monitor the RH in the chambers at the same time. The four different saturated salt solutions were MgCl2, Mg(NO3)2, NaCl, and KCl, were chosen to prepare the atmospheres with the different relative humidity levels. Compared with other salts, MgCl2, Mg(NO3)2, NaCl, and KCl are easy to obtain, stable, and with proper corresponding relative humidity values of 33%, 54%, 75%, and 85% at 25 °C, respectively.

4. Conclusions

Pristine SnO2 and Li+-doped SnO2 composite porous nanofibers with various dopant concentrations were fabricated by a simple electrospinning method. The humidity sensing properties of the as-prepared samples were also studied. It was found that the introduction of alkali ion Li+ into the one-dimensional SnO2 porous nanofiber improves humidity sensing properties. Compared with the pristine SnO2 porous nanofibers, the optimized Li+-doped SnO2 porous nanofibers exhibited an up to 15 times higher response (85% RH) when tested at 5 V and room temperature. Most importantly, the response and recovery times of the Li+-doped SnO2 porous nanofibers were both below 1 s, which is extremely attractive for ultrafast breathing applications. The high humidity sensitivity, the ultrafast response, and the recovery properties could be attributed to the co-contributions of the doping of Li+ ions and the 1D characteristic structure of SnO2 porous nanofibers. This work can highly improve the development of Li+-doped SnO2 porous nanofiber-based direct-current humidity sensors and provide an effective way of developing ultrafast humidity sensors.

Acknowledgments

The work has been supported by research grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51003036) and the Shenzhen Science and Technology Research Grant (No. JCYJ20150629144328079).

Author Contributions

X.X., M.Y., and Z.L. conceived the idea and designed the experiments. X.X., M.Y., and Z.L. led the experiments (with assistance from F.Y.). X.X., M.Y., Z.W., M.Z., and M.L. contributed to data analysis and interpretation. X.X. and M.Y. wrote the paper, and all authors provided feedback.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted without any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Pattananuwat P., Tagaya M., Kobayashi T. A novel highly sensitive humidity sensor based on poly (pyrrole-co-formyl pyrrole) copolymer film: AC and DC impedance analysis. Sens. Actuators B. 2015;209:186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2014.11.111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borini S., White R., Wei D., Astley M., Haque S., Spigone E., Harris N., Kivioja J., Ryhänen T. Ultrafast graphene oxide humidity sensors. ACS Nano. 2013;7:11166–11173. doi: 10.1021/nn404889b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mogera U., Sagade A.A., George S.J., Kulkarni G.U. Ultrafast response humidity sensor using supramolecular nanofibre and its application in monitoring breath humidity and flow. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:4103. doi: 10.1038/srep04103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hong H.P., Lee M.J., Jung K.H., Park C.W., Min N.K. Random networked multi-walled carbon nanotube film as an upper electrode for high-speed capacitive humidity sensors. Thin Solid Films. 2013;546:73–76. doi: 10.1016/j.tsf.2013.04.087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geng W., Yuan Q., Jiang X., Tu J., Duan L., Gu J., Zhang Q. Humidity sensing mechanism of mesoporous MgO/KCl-SiO2 composites analyzed by complex impedance spectra and bode diagrams. Sens. Actuators B. 2012;174:513–520. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2012.08.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shukla S.K., Parashar G.K., Mishra A.P., Misra P., Yadav B.C., Shukla R.K., Bali L.M., Dubey G.C. Nano-like magnesium oxide films and its significance in optical fiber humidity sensor. Sens. Actuator B. 2004;98:5–11. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2003.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Camposeo A., Persano L., Pisignano D. Light-emitting electrospun nanofibers for nanophotonics and optoelectronics. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2013;298:487–503. doi: 10.1002/mame.201200277. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang Y., Li Z., Ma J., Wang L., Yang J., Du B., Yu Q., Zu X. Highly sensitive surface acoustic wave (SAW) humidity sensors based on sol-gel SiO2 films: Investigations on the sensing property and mechanism. Sens. Actuator B. 2015;215:283–291. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2015.03.069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soldano C., Comini E., Baratto C., Ferroni M., Faglia G., Sberveglieri G. Metal oxides mono-dimensional nanostructures for gas sensing and light emission. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2012;95:831–850. doi: 10.1111/j.1551-2916.2011.05056.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maier K., Helwig A., Müller G., Hille P., Eickhoff M. Effect of water vapor and surface morphology on the low temperature response of metal oxide semiconductor gas sensors. Materials. 2015;8:6570–6588. doi: 10.3390/ma8095323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lupan O., Braniste T., Deng M., Ghimpu L., Paulowicz I., Mishra Y.K., Kienle L., Adelung R., Tiginyanu I. Rapid switching and ultra-responsive nanosensors based on individual shell-core Ga2O3/GaN:Ox@SnO2 nanobelt with nanocrystalline shell in mixed phases. Sens. Actuator B. 2015;221:544–555. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2015.06.112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tawale J.S., Gupta G., Mohan A., Kumar A., Srivastava A.K. Growth of thermally evaporated SnO2 nanostructures for optical and humidity sensing application. Sens. Actuator B. 2014;201:369–377. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2014.04.099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ye J., Zhang H., Yang R., Li X., Qi L. Morphology-controlled synthesis of SnO2 nanotubes by using 1D silica mesostructures as sacrificial templates and their applications in lithium-ion batteries. Small. 2010;6:296–306. doi: 10.1002/smll.200901815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paulowicz I., Hrkac V., Kaps S., Cretu V., Lupan O., Braniste T., Duppel V., Tiginyanu I., Kienle L., Adelung R., et al. Three-dimensional SnO2 nanowire networks for multifunctional applications: From high-temperature stretchable ceramics to ultraresponsive sensors. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2015;1:1500081. doi: 10.1002/aelm.201500081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhen Y., Sun F.-H., Zhang M., Jia K., Li L., Xue Q. Ultrafast breathing humidity sensing properties of low-dimensional Fe-doped SnO2 flower-like spheres. Rsc. Adv. 2016;6:27008–27015. doi: 10.1039/C5RA27572E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuang Q., Lao C., Wang Z.L., Xie Z., Zheng L. High-sensitivity humidity sensor based on a single SnO2 nanowire. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:6070–6071. doi: 10.1021/ja070788m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Z., Zhang H., Zheng W., Wang W., Huang H., Wang C., MacDiarmid A.G., Wei Y. Highly sensitive and stable humidity nanosensors based on LiCl doped TiO2 electrospun nanofibers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:5036–5037. doi: 10.1021/ja800176s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song X., Qi Q., Zhang T., Wang C. A humidity sensor based on KCl-doped SnO2 nanofibers. Sens. Actuator B. 2009;138:368–373. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2009.02.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang Z., Zhang Z., Liu K., Yuan Q., Dong B. Controllable assembly of SnO2 nanocubes onto TiO2 electrospun nanofibers toward humidity sensing applications. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2015;3:6701–6708. doi: 10.1039/C5TC01171J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suematsu K., Sasaki M., Ma N., Yuasa M., Shimanoe K. Antimony-doped tin dioxide gas sensors exhibiting high stability in the sensitivity to humidity changes. ACS Sens. 2016;1:913–920. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.6b00323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toloman D., Popa A., Stan M., Socaci C., Biris A.R., Katona G., Tudorache F., Petrila I., Iacomi F. Reduced graphene oxide decorated with Fe doped SnO2 nanoparticles for humidity sensor. App. Surf. Sci. 2017;402:410–417. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.01.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomer V.K., Duhan S. A facile nanocasting synthesis of mesoporous Ag-doped SnO2 nanostructures with enhanced humidity sensing performance. Sens. Actuator B. 2016;223:750–760. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2015.09.139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sabarilakshmi M., Janaki K. A facile and one step synthesis of W doped SnO2 nanopowders with enhanced humidity sensing performance. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2017;28:5329–5335. doi: 10.1007/s10854-016-6191-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tomer V.K., Devi S., Malik R., Nehra S.P., Duhan S. Fast response with high performance humidity sensing of Ag–SnO2/SBA-15 nanohybrid sensors. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2016;219:240–248. doi: 10.1016/j.micromeso.2015.08.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu X., Yin M., Li N., Wang W., Sun B., Liu M., Zhang D., Li Z., Wang C. Vanadium-doped tin oxide porous nanofibers: Enhanced responsivity for hydrogen detection. Talanta. 2017;167:638–644. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2017.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mai L.Q., Chen W., Xu Q., Zhu Q.Y. Effect of modification by poly(ethylene-oxide) on the reversibility of Li insertion/extraction in MoO3 nanocomposite films. Microelectron. Eng. 2003;66:199–205. doi: 10.1016/S0167-9317(03)00047-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luan C., Zhu Z., Mi W., Ma J. Effect of Sb doping on structural, electrical and optical properties of epitaxial SnO2 films grown on r-cut sapphire. J. Alloys Comp. 2014;586:426–430. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2013.10.087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang L., He Y., Hu J., Qi Q., Zhang T. DC humidity sensing properties of BaTiO3 nanofiber sensors with different electrode materials. Sens. Actuator B. 2011;153:460–464. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2010.11.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kannan P.K., Saraswathi R., Rayappan J.B.B. A highly sensitive humidity sensor based on DC reactive magnetron sputtered zinc oxide thin film. Sens. Actuator A. 2010;164:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.sna.2010.09.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arshaka K., Twomey K., Egan D. A ceramic thick film humidity sensor based on MnZn ferrite. Sensors. 2002;2:50–61. doi: 10.3390/s20200050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yadav B.C., Srivastava R., Dwivedi C.D. Synthesis and characterization of ZnO-TiO2 nanocomposite and its application as a humidity sensor. Philos. Mag. 2008;88:1113–1124. doi: 10.1080/14786430802064642. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sakuma H., Kawamura K. Structure and dynamics of water on Li+-, Na+-, K+-, Cs+-, H3O+-exchanged muscovite surfaces: A molecular dynamics study. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2011;75:63–81. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2010.10.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feng P., Yue X.Y., Liu Y.G., Wang T.H. Highly sensitive ethanol sensors based on {100}-bounded In2O3 nanocrystals due to face contact. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006;89:243514. doi: 10.1063/1.2404935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liang Y.X., Chen Y.J., Wang T.H. Low-resistance gas sensors fabricated from multiwalled carbon nanotubes coated with a thin tin oxide layer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004;85:666–668. doi: 10.1063/1.1775879. [DOI] [Google Scholar]