Abstract

The Trc/Ndr/Sax1/Cbk1 family of ser/thr kinases plays a key role in the morphogenesis of polarized cell structures in flies, worms, and yeast. Tricornered (Trc), the Drosophila nuclear Dbf2-related (Ndr) serine/threonine protein kinase, is required for the normal morphogenesis of epidermal hairs, bristles, laterals, and dendrites. We obtained in vivo evidence that Trc function was regulated by phosphorylation and that mutations in key regulatory sites resulted in dominant negative alleles. We found that wild-type, but not mutant Trc, is found in growing hairs, and we failed to detect Trc in pupal wing nuclei, implying that in this developmental context Trc functions in the cytoplasm. The furry gene and its homologues in yeast and Caenorhabditis elegans have previously been implicated as being essential for the function of the Ndr kinase family. We found that Drosophila furry (Fry) also is found in growing hairs, that its subcellular localization is dependent on Trc function, and that it can be coimmunoprecipitated with Trc. Our data suggest a feedback mechanism involving Trc activity regulates the accumulation of Fry in developing hairs.

INTRODUCTION

The conserved nuclear Dbf2-related (Ndr) kinase family has been found to function in various aspects of cell polarity and morphogenesis in yeast, flies, and worms. The Drosophila Ndr is encoded by the tricornered (trc) gene. Mutations in this gene result in clustered and split epidermal hairs and arista laterals and split and malformed bristles (Geng et al., 2000). In arista laterals, trc mutations alter the overall distribution of both actin filaments and microtubules (He and Adler, 2001). trc mutations also cause increased dendritic branching and altered dendritic tiling (Emoto et al., 2004). Similar effects on dendritic branching result from mutations in the Caenorhabditis elegans ndr gene sax-1 (Zallen et al., 2000). In Saccharomyces cerevisae, mutations in Cbk1 result in a failure in bud axial growth and release of the bud from the mother cell (Racki et al., 2000; Bidlingmaier et al., 2001; Colman-Lerner et al., 2001; Du and Novick, 2002; Weiss et al., 2002; Nelson et al., 2003). A defect in axial growth also is associated with mutations in orb6 of Schizosaccharamyces pombe (Verde et al., 1998). There are two ndr homologues in both the human and mouse genomes, but little is known about the in vivo function of the vertebrate genes.

Extensive biochemical studies have been carried out on the human Ndr kinase. In cultured mammalian cells, the protein is largely nuclear and an unconventional nuclear localization sequence is essential for this (Millward et al., 1995). This sequence is conserved across the Ndr family, but it is clear that Ndr kinases are not restricted to the nucleus (Devroe et al., 2004). In yeast, Cbk1 has both nuclear and cytoplasmic functions (Racki et al., 2000; Colman-Lerner et al., 2001; Nelson et al., 2003). It is found in the daughter cell nucleus where it is involved in the activation of the AceII transcription factor. This is essential for the specification of the daughter cell gene expression program (Racki et al., 2000; Colman-Lerner et al., 2001; Nelson et al., 2003). Cbk1 also has been shown to be required for axial growth of the bud, and this is an AceII-independent function (Bidlingmaier et al., 2001; Colman-Lerner et al., 2001; Nelson et al., 2003). Cbk1 is localized to the cortex in the vicinity of the bud neck, and it is thought to function at this location in facilitating axial growth (Bidlingmaier et al., 2001; Colman-Lerner et al., 2001; Nelson et al., 2003). We show here that in the Drosophila wing before hair morphogenesis Trc is cytoplasmic and enriched at the cell periphery. As development proceeds, Trc is found in growing wing hairs in a punctate pattern. We did not detect Trc in pupal wing cell nuclei.

The activity of many kinases is regulated by phosphorylation. Studies of human Ndr have shown that mutations of either or both of two conserved phosphorylation sites to alanine strongly reduced or abolished both basal and okadaic acid-stimulated Ndr activity (Millward et al., 1999). These are also important sites in yeast Ndr-related Dbf2 kinase (Mah et al., 2001). We report here that the human Ndr1 has trc rescue activity, arguing these kinases are functionally equivalent. Mutations in either or both of the two conserved phosphorylation sites in Trc resulted in a dominant negative protein for epidermal development. These observations indicate that Trc is activated by phosphorylation and that this is essential for its function in epidermal morphogenesis. These mutants have proved to be valuable genetic reagents and have allowed us to conveniently screen for interacting genetic regions and genes.

The Ndr family has been found to interact with a family of large conserved proteins in flies, worms, and yeast. The first of these large proteins to be identified was encoded by the Drosophila furry (fry) gene (Cong et al., 2001). Mutations in fry mimic the phenotypes of trc mutants, and genetic experiments have argued that these two genes function in the same pathway. Furthermore, Trc kinase activity is strongly reduced in fry mutants (Emoto et al., 2004). In S. cerevisiae, the Furry relative Tao3/Pag1 functions with Cbk1 in the RAM pathway that regulates axial growth of the bud and daughter cell identity (Nelson et al., 2003). Furthermore, Tao3/Pag1 and Cbk1 can be coimmunoprecipitated and Tao3 is required for full Cbk1 kinase activity. We report here that Trc and Fry can be coimmunoprecipitated.

Control of subcellular location is important in the regulation of many kinases. Evidence from both budding and fission yeasts has suggested that the fry homolog in these systems is involved in controlling Cbk1 and Orb6 location (Du and Novick, 2002; Hirata et al., 2002; Nelson et al., 2003), but the relationship is interdependent, complex, and at least superficially different in the two. In S. cerevisiae mutations in Tao3/Pag1 do not alter the accumulation of Cbk1 in the bud neck, but in the mutant the tight restriction of Cbk1 to the daughter cell nucleus is lost. In most mother/daughter pairs where nuclear staining was seen, it was detected in both mother and daughter nuclei (Nelson et al., 2003). In contrast, Tao3 normally accumulates only at the bud neck and in a Cbkl mutant the amount of Tao3 is slightly increased (Nelson et al., 2003). In S. pombe, homologues of both fry (mor2/cps12) and trc (orb6) function in the same pathway in regulating cellular polarity (Hirata et al., 2002). Overexpressed Mor2 accumulated at both cell ends and the medial region of the cell in an actin-dependent manner (Hirata et al., 2002). Loss of Orb6 resulted in reduced localization of Mor2 (Hirata et al., 2002) in contrast to the increase seen in S. cerevisiae for Tao3 in a Cbk1 mutant. Previous studies on metazoan Ndr and Fry family members have not provided evidence for the subcellular distribution being a point of regulation for their in vivo function, although this seems likely. In this report, we show that in the fly wing the endogenous Trc and Fry proteins both accumulate in a punctuate pattern in growing hairs, which suggests that they could be involved in intracellular transport during hair outgrowth. In fry mutant cells, the amount of Trc in the hair was reduced. In contrast, in trc mutant cells the amount of Fry in the hair increased. We also show that the overexpression of a dominant negative Trc protein resulted in increased accumulation of Fry in developing hairs. These data suggest that a feedback mechanism related to Trc activity regulates the accumulation of Fry in developing hairs.

Disruption of trc/fry function is not the only perturbation that is known to cause multiple hair cells. The antagonism of the actin cytoskeleton by inhibitors also can result in multiple hair cells, although these differ from those seen in trc by resulting in a smaller number of hairs and by the hairs looking stunted (Turner and Adler, 1998). Similarly, the genetic disruption of cytoskeletal components such as zipper (myosin II) and crinkled (myosin VII) results in stunted multiple hairs (Turner and Adler, 1998; Young et al., 1993; Winter et al., 2001). Of particular interest is that multiple wing hair phenotypes also are seen in flies in which Rho family G protein function is altered. Both hypomorphic mutants (rho172BH) and the directed expression of dominant negative mutants (rho1N17) of Rho1 result in the formation of multiple hair cells (Strutt et al., 1997). Genetic interactions indicated that Rho1 functions downstream of Fz and Dsh in the wing (Strutt et al., 1997). The Drosophila Rho-associated kinase (Drok) was later shown to be required for normal hair morphogenesis and to be downstream of Fz and Dsh (Winter et al., 2001). The overexpression of dominant negative Drac1 and Dcdc42 also result in hair phenotypes, suggesting that several Rho family GTPases function in hair morphogenesis (Eaton et al., 1996). In sensory neuron dendrites, Trc inhibits DRac (Emoto et al., 2004); however, recent experiments indicate that Drac gene function is not essential for hair or bristle morphogenesis (Hakeda-Suzuki et al., 2002). Progressive loss of the three Rac homologues in flies (Rac1, Rac2, and Mtl) lead first to defects in axon branching, then to guidance, and finally to growth (Hakeda-Suzuki et al., 2002). However, triple mutant cells elaborated normal hairs and bristles. Thus, the mechanism by which dominant negative Drac proteins cause a wing hair phenotype is unclear, and it seems unlikely that an important function of Trc in wing cells is to inhibit Rac. The Ral GTPase, which is activated by RalGDS, one of the effector proteins for Ras, also has been implicated in regulating the cytoskeleton in Drosophila epidermal cells (Sawamoto et al., 1999). The directed expression of dominant negative mutants of Drosophila Ral (DralS25N) caused split and clustered hairs and similar defects in bristles (Sawamoto et al., 1999). Dral also was shown to inhibit the Drosophila c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway (Sawamoto et al., 1999). We used a genetic approach to examine the relationship between Trc and various G proteins during wing hair morphogenesis. We found evidence for strong interactions between these genes. Our data suggests that these proteins function as a regulatory network that regulates the cytoskeleton in wing development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid Constructs for Germline Transformation

Site-directed Mutagenesis For generating the trc kinase mutants, the complete trc cDNA pBS (Geng et al., 2000) were used as the template. The following oligonucleotides were used to introduce amino acids substitution with the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). For S292A mutation, GTTCCCACGGTGGCGTAGGCGAGGGCG; for T453A mutation, CCTCGAATCGTTTGTAGGCGTAGTTGATAAAGACCC; for S292E mutation, GGCGTTCCCACGGTCTCGTAGGCGAGGGCGC; for T453E mutation, GCACCTCGAATCGTTTGTACTCGTAGTTGATAAAGACC; for K122A mutation, CGCTTTGCGCAGCACGGCCATGGCGTACACATG; and for S292A+T453A and K122A+T453A double mutations, templates of S292A, S292E and K122A were used consecutively, separately. The appropriate XhoI-XbaI fragment was inserted into the polyclonal region of the pUAST vector (Brand and Perrimon, 1993).

Note that analysis of trc cDNA clones revealed that alternative splicing results in the formation of two trc mRNAs. The longer mRNA encodes a protein (TrcL) with four additional amino acids (267-SLSC-270) (Geng et al., 2000). Previous transgenic experiments had used trcS (Geng et al., 2000). To determine whether there was any obvious functional difference we generated UAS-trcL transgenic flies and compared the consequences of directing expression of either form of the protein. No differences were seen (Figure 2d, rescue of UAS-trcshort). We concluded that the two forms of trc are equivalent and used the Trc long form (TrcL) as the starting point for all mutagenesis. In the long form, Ser292 and Thr453 correspond to Ser288 and Thr449 of the short form.

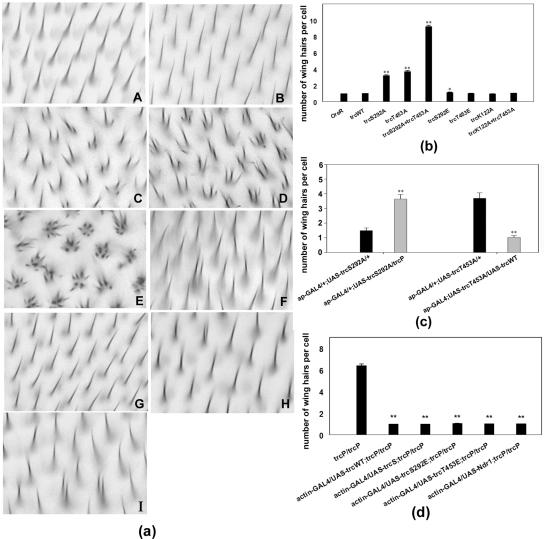

Figure 2.

Directed expression of Trc mutants can result in multiple hair cells similar to those seen in trc loss of function mutants. (a) Wing phenotypes. A-J show bright-field micrographs of the same region of wings of the wild-type and tested genotypes: OreR (A), ap-GAL4/UAS-trcWT (B), ap-GAL4/UAS-trcS292A (C), ap-GAL4/UAS-trcT453A (D), ap-GAL4/UAS-trcS292A+T453A (E), ap-GAL4/UAS-trcS292E (F), ap- GAL4/UAS-trcT453E (G), ap-GAL4/UAS-trcK122A (H), and ap-GAL4/UAS-trcK122A+T453A (I). (b) Average number of hairs per cell is presented. The overexpression of wild-type, the single glu mutants (S292E and T453E), lys122ala, or lys122ala+thr453ala had little effect. Most cells formed a single hair. One or two cells shown in F, I, and J produced a double hair. Moderate multiple hair cell phenotypes were seen when either of the single ala mutants were expressed (S292A and T453A). In these wings, there was average of four hairs per cell. Dramatic, strong phenotypes resulted from the expression of the S292A T453A double mutant. Error bars represent the SE of the mean. In several cases, the error bars were too small to be visible. Each genotype was compared with Oregon R by using a t test, and significant differences were noted. (c) Evidence the mutants acted as dominant negatives. To determine whether the phosphorylation site ala mutant proteins decreased or increased Trc activity, we examined the consequences of a reduction in Trc dose or coexpression of trcWT. Shown are data for flies that were ap-GAL4/+; UAS-trcS292A/+ versus ap-GAL4/+; UAS-trcS292A/trcP, and ap-GAL4/+; UAS-trcT453A/+ versus ap-GAL4/+; UAS-trcT453A/UAS-trcWT. Note the large degree of rescue that resulted from the coexpression of the wild-type protein, implying that the ala mutants were acting as dominant negative proteins. Consistent with this interpretation, a mutation in the endogenous trc gene acted as a dominant enhancer of the ala mutant protein. Significant differences from t test comparisons are indicated. (d) Rescue of the trcP/trcP lethal mutant by driving expression of UAS-trcS292E, UAS-trcT453E, UAS-trcWT, UAS-trcshort (see Materials and Methods for description of trcshort) and UAS-ndr1 by using actin-GAL4. The importance of the phosphorylation sites was further assayed by testing the ability of various mutant proteins to provide trc rescue activity. We generated flies that were actin-GAL4/UAS-trcX; trcP/trcP. None of the Ala mutants showed rescue activity. The UAS constructs that contained trcWT, NDR1, trcS292E, and trcT453E completely rescued the lethality of trc mutants and also resulted in rescue of the wing phenotype. We compared the number of hairs per wing cell for each rescued wing sample and data for trcP/trcP mutant clones by using a t test. All results were highly significant (P ≪ 0.001). We also compared the rescue achieved by expression of trcL (trcWT) with the other rescuing constructs. These did not show highly significant differences (our unpublished data). Note **P value is ≪ 0.001, which means a highly significant difference; * means the P value between two samples is between 0.001 < P < 0.05, which represents a likely difference; and no * means the P value between the two samples is >0.05, which represents no significant difference.

Genetics

Flies were grown on standard media at 25°C. Mutant stocks were either obtained from the stock center at Indiana University or generated in University of Virginia. Targeted expression of UAS-driven transgenes (Brand and Perrimon, 1993. trc transgenes were tested for their ability to rescue lethality in flies that were UAS-trcX/+; trcP/act-GAL4 trcP. This genotype results in a mild overexpression of the transgenic trc in a trcP/trcP lethal background. This level of expression does not result in any gain of function phenotype. To characterize the consequences of overexpression, we examined ap-GAL4 (or ptc-GAL4)/+; UAS-trc/+flies. Slight differences in the average number of hairs per cell for a transgene were due to using independent lines or different GAL4 drivers.

Clonal Analysis

Somatic clones were generated using the FRT/FLP system (Xu and Rubin, 1993). Pupal wing clones were marked by the loss of green fluorescent protein (GFP). For examining trc or fry phenotypes and subcellular localizations in clones, the following flies were crossed: w; vg-GAL4::UAS-FLP/CyO; Ubi-GFP FRT80/TM6, trcP FRT80/TM6B, or fryTAUS1 FRT80/TM6B.

Antibodies

Antibodies against Fry antibody were raised in rabbits. Synthetic peptides corresponding to the C-terminal sequence of fly Fry (C-CGSASGNSHYSEQDIVTNL) were used as antigens. Anti-Trc polyclonal antibody was generated by immunizing guinea pig with the C-terminal 200 amino acids of Trc protein purified from Escherichia coli, which was transformed with truncated trc cDNA. Monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody was purchased from SigmaAldrich (St. Louis, MO). Monoclonal anti-Armadillo antibody was purchased from The Developmental Biology Hybridoma Bank (University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA). Alexa 488- and Alexa 568-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR).

Cell Culture and Coimmunoprecipitation

Cell culture, transfection, and immunoprecipitation were carried out by standard procedures (Emoto et al., 2004). S2 cells were cotransfected with pAct-Gal4 (4 μg) and either mock pUAST vector (6 μg), pUAST-Trc-FLAG (6 μg), or pUAST-Trc-FLAG (6 μg) and pUAST-N-Fry-3 × Myc (6 μg). N-Fry-3 × Myc fragment encodes amino acids 1-1637 of the Fry protein.

Immunostaining

Immunostaining was done by standard procedures. Briefly, tissues were fixed with paraformaldehyde, washed, blocked, and stained overnight at 4°C in primary antibody phosphate-buffered saline, 0.2% Triton X-100 (PBST) and were blocked in PBST, 10% normal goat serum (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min. Secondary antibodies were obtained from Molecular Probes and were applied for 2-3 h at room temperature. In some experiments, F-actin was stained using a fluorescent phalloidin.

Microscopy and Photography

The immunostaining results were studied by confocal microscopy by using either a Nikon laser scanning cofocal microscope or an Atto CARV spinning disk confocal attached to a Nikon microscope. Other slides were observed under an Axioskop microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). Bright field images of wings were obtained using a Spot digital camera (National Diagnostics, Atlanta, GA). Adobe Photoshop was used to compose figures.

Scoring of Mutant Wings

Wings were mounted in Euparal (Asco Labs, Manchester, United Kingdom) and examined under bright-field microscopy by using approaches described previously (Wong and Adler, 1993). Because the wing is not uniformly affected by trc/fry mutations, a specific region within the “C cell” (5 × 40 cells) was chosen for scoring the number of hairs per wing cell for each ap-GAL4 or ptc-GAL4-driven UAS-mutant.

Statistical Analysis

Microsoft Excel and S-Plus6 programs were used for comparing different genotypes.

RESULTS

Mutations in trc Induce a Cell Shape Change and Altered Actin Distribution

Mutations in Trc or Fry are larval lethal, hence their function in the development of the adult epidermis has principally been studied in genetic mosaics (Geng et al., 2000; Cong et al., 2001). In previous studies, we focused on the clustered and split wing hair phenotype (Geng et al., 2000; Cong et al., 2001). More recently, it became clear that the trc and fry wing phenotypes were more complicated. In a wild-type wing, cells are typically hexagonally shaped and packed into a regular array. Mutant cells in large clones often had an irregular shape, and their average cross-sectional area was ∼1.6-fold larger than control neighboring cells (Figure 1, A2 and A3). Actin staining was increased below the apical surface in a manner that was similar to but much less severe than that in slingshot, which encodes a Lim kinase (Niwa et al., 2002) or flare (Adler, unpublished data) mutants. Thus, it is clear that Trc and Fry function in regulating cell shape before hair development. Actin staining also showed the typical multiple hair cell phenotypes of trc and fry cells (Figure 1, B2 and B3). We further found that trc and fry cells are typically (but not always) delayed in hair morphogenesis (Figure 1, A3).

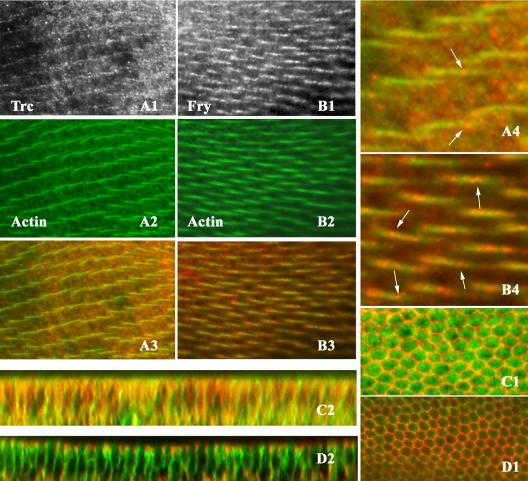

Figure 1.

trc Mutant phenotype in wing clones. Part of a pupal wing that contains a trc clone marked by a loss of GFP. (A1 and B1) GFP. (A2 and B2) Actin staining. (A3 and B3) Merged images. Top, clone where hair development is strongly delayed. Bottom, clone where the mutant cells have formed hairs. Note the enlarged and irregularly shaped clone cells compared with the wild-type cells. Apical actin staining is stronger than in neighboring wild-type cells. Note the multiple hair cells in the clones and the delay in hair morphogenesis by some clone cells. fry mutant clones show similar phenotypes (our unpublished data).

Human Ndr1 Has trc Rescue Activity

The trc human homolog ndr1 shares 68% sequence identity (77% catalytic domain identity) with Trc (Millward et al., 1995). We generated transgenic flies that carried a UAS-ndr1 (human) transgene and found that it could completely rescue both the lethality and mutant wing hair phenotype of trc (Figure 2d). We concluded that the two proteins are functionally equivalent and that information obtained from experiments on the human protein would likely translate faithfully to Trc. As reported below, this proved to be the case in experiments on two regulatory phosphorylation sites.

Two Conserved Ser and Thr Phosphorylation Sites Are Required for trc Function In Vivo

We generated transgenic flies that carried point mutations at either or both of two regulatory sites identified in human Ndr1. Five different types of trc mutant genes were analyzed: trcS292A, trcT453A, trcS292A+T453A, trcS292E, and trcT453E. The trcS292A, trcT453A, and trcS292A+T453A mutations were analogous to ndr1S281A, ndr1T444A, and ndr1S281A+T444A mutations, which were shown to markedly reduce basal kinase activity and abolished its ability to be stimulated by okadaic acid (Millward et al., 1999). None of these three mutant transgenes could rescue trcP/trcP lethality. In contrast, the trcS292E, trcT453E mutants retained full rescue activity (Figure 2d). We also examined these mutant transgenes to see whether their overexpression resulted in a mutant phenotype. In control experiments, we found that driving the expression of UAS-trcWT (or other trc transgenes) with ap-Gal4 resulted in flies whose wings either curled down and/or were held in an upright position (our unpublished data). The basis for this gain of function is unclear but may involve a change in cell size in the dorsal wing cells that ap-GAL4 drives expression in. Driving the expression of UAS-trcS292A, UAS-trcT453A, and UAS-trcS292A+T453A with ap-Gal4 resulted in substantial numbers of multiple hair cells (Figure 2a, C-E). In most cases, one or two relatively normalsized hairs were clustered together with short hairs. These phenotypes were weak versions of those produced by loss of function trc alleles. No effect on hair polarity was seen. In comparison, the overexpression of UAS-trcWT, UAS-trcS292E, or UAS-trcT453E resulted in only a very small number of multiple hair cells (Figure 2a, B, F, and G, and d). The phenotypes produced by overexpression of independent insertions of each mutant transgene varied only slightly. No substantial differences in phenotype strength were found between the two single mutants trcS292A and trcT453A. The single alanine mutants resulted in an average of ∼1.5-4 hairs per cell, and many cells produced a single hair. In contrast, there was a striking difference between single and double mutants. trcS292A+T453A double mutants resulted in an average of 10-12 hairs per cell with some cells producing 18 or more hairs. Essentially all cells where the double mutant proteins were overexpressed produced multiple hairs. The trc mutants affected epidermal hairs in other body regions (e.g., notum), in a similar way. Overexpressing several of the mutated Trc proteins (TrcS292A, TrcT453A, and TrcS292A+T453A) by using either ap-GAL4 or neur-GAL4 also resulted in split/branched bristles that resembled those seen in trc loss of function mutants (particularly in the abdomen) and also deformed bristles that were short, fat, bent, and twisted (our unpublished data). In trc loss of function mutants, a similar splitting phenotype also was seen in the arista laterals (Geng et al., 2000). UAS-trcmutant transgenic lines that expressed the transgene in the arista caused a similar lateral branching (our unpublished data). We hypothesized that the UAS-trcS292A, UAS-trcT453A, and UAS-trcS292A+T453A phenotypes were caused by a dominant negative effect. To address whether this was the case, wild-type Trc protein was expressed along with the dominant negative mutants (e.g., w;ap-Gal4/UAS-trcWT; UAS-trcmutant/+). The morphological defects in the wing and notum resulting from the ap-GAL4-driven mutants were largely rescued by coexpression of the wild-type Trc protein (Figure 2c). Similarly, we found that reducing the number of functional trc genes from two to one enhanced the phenotypes obtained from overexpressing the mutant proteins (Figure 2c). We concluded that the phosphorylation site mutations to ala resulted in dominant negative proteins.

Trc Kinase Activity Is Essential for In Vivo Function

The analysis of sequence changes associated with mutations in the endogenous trc gene suggested that kinase activity was essential for trc function in the epidermis (Geng et al., 2000). To test this further, we generated a mutation in lysine122 (to alanine), which is an invariant active site residue in all protein kinases and essential for catalytic activity. We found that Trc-lys122ala had no rescue activity. An equivalent mutation in the human Ndr1 resulted in an inactive enzyme (Millward et al., 1995). The overexpression of this kinase dead protein did not cause a strong trc-like phenotype (Figure 2a, H). We hypothesized that the kinase dead protein could not bind to the substrate and hence could not act as a dominant negative. To test this, we made a trcK122A+T453A double mutant and found that the dominant negative phenotype associated with trcT453A was suppressed by the presence of the lys122ala mutation (Figure 2a, I). We propose that this is due to the kinase inactive form of Trc being unable to compete with the endogenous Trc for binding substrate. This could be due to a need for an autophosphorylation to allow Trc to bind substrate, but this autophosphorylation would have to be at a site other than Ser292 or Thr453.

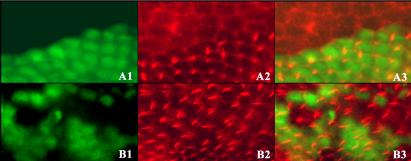

Trc Genetically and Physically Interacts with Fry

Trc kinase activity in vitro is dependent on Furry (Emoto et al., 2004) and double mutant analysis suggested that these genes functioned in a common pathway during Drosophila wing development (Cong et al., 2001). We found that reducing the dose fry from two to one enhanced the trc dominant negative phenotype, consistent with Furry activating Trc (Figure 3A). This interaction indicated that we could use the trc dominant negative phenotype to screen for mutations in genes that functioned with Trc. We also tested for a physical interaction between Trc and Fry by cotransfecting a full-length trc cDNA tagged with FLAG (trc-FLAG) and an amino-terminal fragment of fry (amino acids 1-1637) tagged with Myc (N-fry-Myc) into Drosophila S2 cells. We detected FLAG-tagged Trc by Western blotting of Myc immunoprecipitates from lysates of cells coexpressing Trc-FLAG and N-Myc-Fry (Figure 3B), providing evidence of a physical interaction between Trc and the N-terminal fragment of Fry.

Figure 3.

Genetic and physical interaction between trc and fry. (A) Flies that carried each of the trc ala single or double mutants with or without the presence of one copy of fryP. The expression of the UAS-trc transgenes was driven by ap-GAL4. We found that fry dominantly enhanced the phenotypes of each of the trc mutants. A similar enhancement is also seen with a Deficiency for the fry gene (our unpublished data). Statistical analyses as in Figure 2. (B) Trc and N-Fry (Fry1-1637) coimmunoprecipitate in an S2 cell lysate. Cells were transfected with UAS-FLAG-Trc and/or UAS-N-Fry-3 × Myc. Top, Western blotting using anti-FLAG antibody to detect Trc after immunoprecipitation with an anti-Myc antibody that brought down N-Fry-3 × Myc protein complex. The lower band in this panel is likely IgG and serves as a loading control. The bottom two panels show the results from Western blotting analysis of the whole cell lysate by using anti-FLAG or anti-Myc antibody.

Fry and Trc Are Interdependent and Localize Similarly to the Cell Cortex and Wing Hair

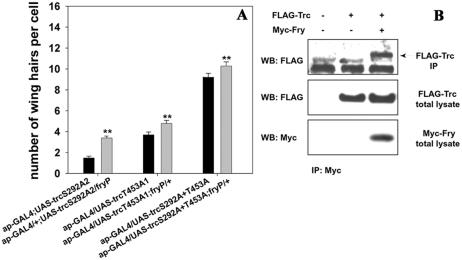

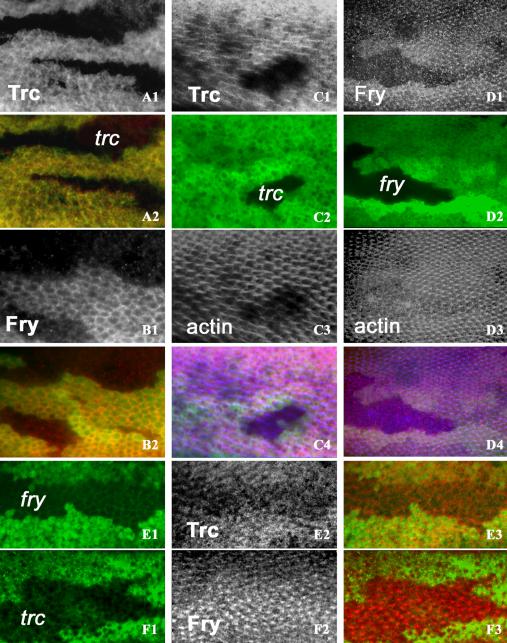

The Trc protein was detected by immunostaining and found to be cytoplasmic in pupal wing cells and to preferentially accumulate at the cell periphery (Figure 4, A1 and A2). The staining was primarily punctuate suggesting Trc might be associated with vesicles or other organelles. We did not see Trc in pupal wing cell nuclei. As a control for antibody specificity, we stained pupal wings and wing discs carrying trc mutant cells marked by a loss of GFP. The mutant cells showed only a low level of background staining. Later in development, we found Trc present in growing hairs (Figure 4, C1-C4). Some staining was seen in the cytoplasm and in all locations the staining had a punctuate appearance (Figure 5, A1-A4). We also double stained OreR pupal wings with anti-Trc and anti-Armadillo antibodies to locate the Trc protein along the apical/basal axis. Armadillo protein is primarily located apically in the adherens junction and also basally in hemidesmosomes. Trc protein was widely distributed and enriched over much of the lateral membrane surface (Figure 5, C1 and C2). Trc subcellular localization was cell type specific. In salivary gland cells, Trc was primarily present at the cell cortex but some staining also was seen in the cytoplasm, at the periphery of the nucleus, and in the nucleoplasm (Supplementary Figure 1, A1 and A2). In fat body cells, the staining was strongest in the nucleus (Supplementary Figure 1, B1 and B2). To address the question of whether the presence of Fry was essential for Trc localization, we stained Trc in fryTAUS1 clones. The level of Trc in growing hairs seemed reduced in fry mutant cells (Figure 4, E1-E3), suggesting that Fry helped recruit or stabilize Trc in growing hairs. It is possible that a delay in hair formation in fry clones could be caused by the reduced recruitment of Trc or that the delay in hair formation could cause the reduced Trc staining.

Figure 4.

Trc and Fry subcellular localizations in wing cells and their interdependency. Homozygous trc or fry clones on the wing were generated by FLP/FRT recombination. The clones are marked by loss of GFP fluorescence (green). Only antibody staining or actin staining are in grey scale to increase contrast. All samples are pupal collected at 26-30 h after white prepupae (before hair formation) or 32-36 h after white prepupae (after hair formation). (A1 and A2) A trc clone (labeled in A2) stained before hair formation. Note in the clone that there is a loss of Trc staining, showing the specificity of the antibody. Surrounding wild-type cells show both cytoplasmic and cell periphery Trc staining. Trc staining (A1) and merge of Trc (red) staining (A2) and GFP staining (green). (B1 and B2) A fry clone stained before hair formation. Fry staining is more prominently at the cell periphery than Trc. Staining is lost in the clone cells showing the specificity of the antibody. (B1) Fry staining. (B2) Merge of Fry (red) staining with GFP staining. (C1-C4) A trc clone stained after hair formation. Note in the clone there is a loss of the Trc accumulation and disruption of hair formation as reported on by actin staining. Surrounding wild-type cells show Trc in the hair in a punctuate pattern. (C1) Trc staining. (C2) GFP staining. (C3) Actin staining. (C4) Merge of Trc (red), GFP (green), and actin (blue). (D1-D4) A fry clone stained after hair formation. Note in the clone there is a loss of the Fry accumulation and disruption of actin cytoskeleton. The surrounding wild-type cells show Fry in the hairs. (D1) Fry staining. (D2) GFP staining. (D3) Actin staining. (D4) Merge of Fry (red), GFP (green), and actin (blue). The bottom two panels show the interdependency of Trc And Fry accumulation. Clones were marked by the loss of GFP (left), antibody staining (middle, in grey scale), and merged images (right, Trc or Fry in red). (E1-E3) A fry clone stained with anti-Trc antibody early in hair morphogenesis. Note the Trc signal is stronger in the wild-type cells than in the neighboring clone cells. (F1-F3) A trc clone stained with anti-Fry antibody after hair formation. Fry hair staining is substantially increased in the trc clone. In all panels, antibody staining is labeled as Trc or Fry and clones are labeled by trc or fry.

Figure 5.

Trc and Fry partially overlapping with actin in wing hairs. (A1-A4 and B1-B4) OreR pupal wings double staining with anti-Trc and phalloidin (to stain F-actin) or anti-Fry antibody with phalloidin after hair formation. Anti-Trc staining (A1), actin staining (A2), and a merged image (A3). A4 is the blow up image showing the punctate pattern of Trc distribution. Arrowheads point to bright regions of staining. Anti-Fry staining (B1), actin staining (B2), and a merged image (B3). B4 is a blow up image illustrating the punctuate staining of Fry in hairs. Arrowheads point to the accumulations of Fry in the hairs. (C1-D2) Twenty-eight-hour OreR pupal wings double stained for Fry and Armadillo or Trc and Armadillo. Fry (or Trc) is in green and Armadillo in red. (C1) An XY section shows the strong cell outline staining of Arm and the broader staining of Trc. (C2) A z section from the same wing showing the relative restriction of Armadillo to the adherens junction and hemidesmosomes and that Trc staining is seen over a wide range of the lateral cell surface. (D1) An XY section shows the strong cell outline staining of Arm and the peripheral staining of Fry. (D2) A z section from the same wing showing the relative restriction of Arm to the adherens junction and that Trc staining is seen over a wide range of the lateral cell surface.

We raised anti-Fry antibody and established that it was specific for the Fry protein in Drosophila wing tissue by staining pupal wing and wing discs that carried fryTAUS1 homozygous clones. The mutant cells showed only faint background staining (Figure 4, B1 and B2). The staining of the neighboring wild-type cells showed that the endogenous Fry protein was principally located at the cell periphery before hair initiation and in hairs during their outgrowth (Figure 4, D1-D4). Some staining was seen in the cytoplasm and in all locations the staining had a punctuate appearance (Figure 5, B1-B4). Double staining for Fry and Armadillo showed that Fry was evenly distributed over a large portion of the lateral cell membrane. It was not seen in the adherens junctions colocalized with Armadillo (Figure 5, D1 and D2). These staining patterns were reminiscent of that seen for Trc, although the pattern was routinely more distinct for Fry than Trc. The punctuate nature of the staining for both Fry and Trc raises the possibility that they are part of a vesicle or other small organelle. These putative vesicles did not stain positively for F-actin. We stained for Fry in salivary gland and fat body and observed a staining pattern that was similar to Trc (Supplementary data “C1-D2”). One difference was that Fry seemed to accumulate more prominently at the nuclear membrane than Trc.

To determine whether Trc function was required for Fry accumulation or localization, we stained pupal wings that carried clones mutant for trc. Interestingly, we found that more Fry was recruited to the hairs in the trc clones than in neighboring wild-type cells (Figure 4, F1-F3). The increase in Fry accumulation in trc mutant hairs suggests that Trc activity negatively regulates the recruitment of Fry to hairs.

We next asked whether the phosphorylation status of Trc might be part of the mechanism that regulates Fry localization. To test this, we examined the distribution of Fry in pupal wings where ptc-GAL4 drove the expression of UAS-trcWT, UAS-trcS292A+T453A, or UAS-trcS292E+T453E. We did not see a major effect on the accumulation of Fry due to the directed expression of wild-type Trc (Figure 6, A2 and B2). However, we consistently found increased Fry localized to hairs in cells where a dominant negative Trc was overexpressed (Figure 6, C2).

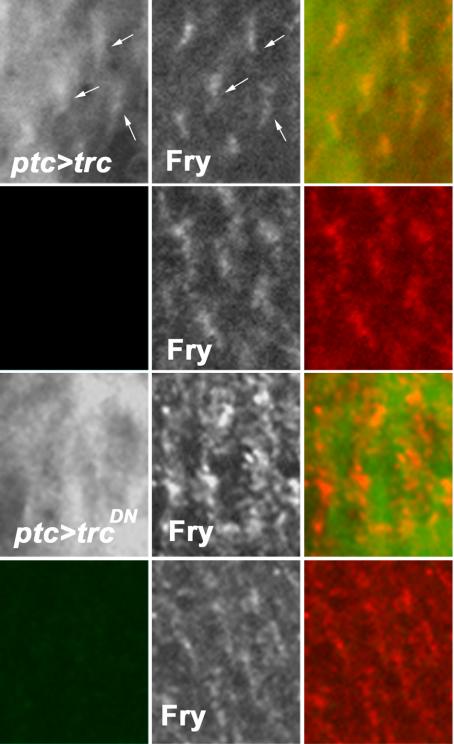

Figure 6.

Fry staining pattern is dependent on active Trc. Thirty-six to 40 hr pupal wings from ptc-Gal4 UAS-trcX animals were stained with polyclonal anti-Fry (generated in rabbit) and monoclonal anti-FLAG (Sigma-Aldrich) antibodies (the trc transgene was tagged with a FLAG epitope at the N-terminal region). ptc-Gal4 drives expression in a stripe down the center of the wing. This domain is bounded by wing veins. In this composite, we compare the staining in the ptc domain and in neighboring cells just lateral to the vein. Top, cells within the ptc domain that are overexpressing wild-type trc. Left, overexpressed Trc. Hair staining (arrows) can be seen, but the background is high due to over expression. Middle, Fry staining, which seems normal. Right, the merge. The second row shows a neighboring region of cells that is outside of the ptc domain. We see no evidence of FLAG staining and Fry staining (middle) seems normal. The lower two rows of panels are equivalent micrographs except that a dominant negative Trc (TrcS292A+T453A) is being overexpressed. Note that hair staining is no longer seen for the overexpressed Trc (left) and Fry staining is increased (middle). The staining for FLAG is not even across the cells, but the brighter regions no longer line up with the brighter Fry staining in the hair. The bottom row shows a region of the same wing just outside of the ptc domain. Once again, we see no FLAG staining and Fry staining is normal.

Trc Hair Localization Is Dependent on Its Phosphorylation

The subcellular localization of overexpressed wild-type and mutant Trc proteins was examined using an amino terminal FLAG epitope. We found the overexpressed wild-type protein to be localized similarly to the endogenous protein. In pupal wing cells, the tagged Trc protein was seen at the lateral cell periphery and in the growing hair.

There are examples where the phosphorylation of a kinase leads to its being localized to a particular subcellular domain (Hing et al., 1999). This did not seem to be the case for Trc before hair initiation or in salivary gland cells (our unpublished data) as the mutant protein showed the same location as the wild-type endogenous protein (our unpublished data).

We saw the recruitment of the overexpressed wild-type Trc to growing hairs, but this was reduced for the mutant proteins (Figure 6, A1 and C1). These observations suggest that during hair outgrowth, the subcellular localization of Trc might be regulated by phosphorylation per se, although we cannot rule out an indirect effect associated with the presence of the dominant negative protein.

Wing Hair Integrity Is Regulated Simultaneously by the Trc/Fry, Rho1/Drok, and Dral/JNK Signaling Transduction Pathways

The clustered wing hair phenotype seen in trc flies resembled defects in flies in which Rho family signaling is perturbed through genetic disruption of Rho1, Dcdc42, or Drac1 (Eaton et al., 1995). To determine whether the Rho pathway interacts genetically with trc, we crossed ap-GAL4/+; UAS-trcT453A flies to loss of function mutants of Rho family GTPases, including RhoAE3.10, Dcdc422, Drac1J11, and Drac1EY05848. All dominantly enhanced the trc dominant negative phenotype (Table 1).

Table 1.

Genetic interaction test of Trc and small Rho GTPase members Dral GTPase and their effectors

| Genotype | Interaction* | Ave | SE |

|---|---|---|---|

| ap-GAL4/+;UAS-trcT453A2/+ | 2.69 | 0.07 | |

| Ap-GAL4/+;UAS-trcT453A2/Rac1[J11] | Enhancement | 3.86 | 0.12 |

| ap-GAL4/+;UAS-trcT453A2/Rac1[EY05848] | Enhancement | 4.32 | 0.15 |

| ap-GAL4/+;UAS-trcT453A2/+ | 2.79 | 0.07 | |

| ap-GAL4/Rho1[E3.10];UAS-trcT453A2/+ | Enhancement | 4.94 | 0.15 |

| ap-GAL4/RhoGEF22;UAS-trcT453A2/+ | Enhancement | 4.04 | 0.08 |

| ap-GAL4/UAS-DrokK116G; UAS-trcT453A2/+ | Enhancement | 3.22 | 0.11 |

| w cdc422;ap-GAL4/+;UAC-trcT453A2/+ | Enhancement | 3.35 | 0.09 |

| ap-GAL4/+;UAS-trcT453A2/+ | 2.84 | 0.07 | |

| ap-GAL4/+;UAS-trcT453A2/UAS-DralG20V | Enhancement | 5.83 | 0.12 |

| ap-GAL4/+;UAS-trcT453A2/UAS-DralS25N | Suppression | 1.74 | 0.06 |

| ap-GAL4/UAS-GrafdsRNA;UAS-trcT453A2/+** | Enhancement | 4.35 | 0.10 |

| ap-GAL4/Vimar[KG6722];UAS-trcT453A2/+** | Suppression | 1.51 | 0.06 |

| ap-GAL4/bsk2;UAS-trcT453A2/+ | Enhancement | 3.84 | 0.07 |

The number of counted cells is 200 for all the fly strains. Genetic interactions were scored as the effect of loss of one wild-type copy of the genes tested on the dominant effect on splitting wing hair phenotype from ap-GAL4 induced overexpression of TrcT453A.

Statistical significance was determined by Student's t test (P < 0.001).

Graf and Vimar are the DralGAP and DralGEF, respectively.

In addition to Rho1, we found that a weak allele of the Rho GEF RhoGEF22 could enhance the trc dominant negative phenotype. Further evidence of an interaction between Rho1 and Trc came from our observation that co-overexpression of dominant negative RhoA (RhoAN17) and Trc (TrcT453A) driven by ap-GAL4 induced synthetic lethality. These results indicated that Rho1 functions with Trc/Fry in regulating wing hair morphogenesis and in other developmental processes.

The co-overexpression of TrcDN with Rac1DN resulted in a strong enhancement of the multiple hair cell phenotype (our unpublished data). Loss of function alleles of Dcdc42 and Drac1, Dcdc422, and Drac1J11 had a much weaker dominant-enhancing effect than the dominant negative proteins. This is not surprising because only the dominant negative Drac1 can induce multiple hair cells (Eaton et al., 1996). It could be due to the presence of multiple redundant pathways or due to a loss of specificity associated with overexpression. For example, highly expressed dominant negative Drac1 could be disrupting cross-talk between pathways (e.g., Rho and Trc).

The Ral GTPase is activated by RalGDS, which is one of the effector proteins for Ras. In previous studies using en-GAL4 to drive overexpression of dominant negative Dral, DralS25N resulted in multiple wing hair cells and in split and malformed bristles (Sawamoto et al., 1999). These phenotypes were genetically suppressed by loss of function mutations in basket (bsk), which encodes the Drosophila JNK (Sawamoto et al., 1999). We crossed dominant negative and constitutively active mutants of Dral (i.e., DralS25N and DralG20V) to a dominant negative Trc. We observed almost a complete rescue of the trc dominant negative phenotype by DralS25N and a dramatic enhancement by DralG20V (Table 1). We also examined two genes thought to regulate the activity of Dral. Consistent with previous results, DralGEF and Dral-GAP, respectively, partially rescued and greatly enhanced the trc dominant negative phenotype (Table 1). Previous experiments found that Dral negatively regulated Drosphila JNK (Basket [bsk]) (Sawamoto et al., 1999). We found that bsk2 dominantly enhanced the trc dominant negative phenotype (Table 1). Thus, we suggest that trc might function in parallel with Dral-JNK to regulate the actin cytoskeleton.

DISCUSSION

Trc Requires Phosphorylation on Ser-292 and Thr-453 for In Vivo Function

Related human and yeast kinases contain a pair of conserved phosphorylation sites corresponding to Ser-281 and Thr-444 in Ndr (Hanks and Hunter, 1995; Millward et al., 1995). In vitro protein kinase activity assays on human Ndr1 and in vivo functional tests for Yeast Dbf2 have confirmed the critical importance of the two conserved sites (Millward et al., 1999; Mah et al., 2001). We found that mutations of these sites in Trc to alanine, which cannot be phosphorylated, resulted in a loss of rescue activity and in dominant negative proteins. We hypothesize that the dominant negative behavior of these mutants arises from the nonproductive binding of targets to an inactive (or low-activity) mutant Trc protein competing with the productive binding of the endogenous Trc protein.

Autophosphorylation at Ser281 (and to a lesser extent Thr444) in Ndr1 is thought to be important for kinase activity (Millward et al., 1995; Devroe et al., 2004; Stegert et al., 2004). Surprisingly, we found that Ser292Ala and Thr453Ala act as dominant negative proteins, whereas Lys122Ala and Lys122Ala Thr453Ala do not. This argues that the dominant negative behavior of Ser292Ala and Thr453Ala is not simply due to their lacking activated kinase activity. One possibility is that a second autophosphorylation is important for Trc to be able to bind substrate. In the complete absence of Trc kinase activity (i.e., Lys122Ala), this site would not be phosphorylated and this would result in the inactive Trc not competing for substrate binding and hence being unable to act as a dominant negative protein. An additional Ca2+-dependent phosphorylation site (Thr74) has also been proposed to be important for Ndr1 regulation (Bhattacharya et al., 2003; Tamaskovic et al., 2003a,b). It will be interesting to determine whether Drosophila Trc also is activated by Ca2+ in a similar way and whether Thr74 could be the hypothesized second autophosphorylation site.

Trc and Fry Function in a Common Signaling Pathway

Several observations argue that Trc and Fry function in a common signaling pathway to regulate the actin cytoskeleton during hair, bristle, lateral, and dendrite morphogenesis. In both yeast and flies, Fry is essential for Trc/Cbk1 kinase activity (Nelson et al., 2003; Emoto et al., 2004). In this article, we obtained in vivo evidence for this as a reduction in Fry dose enhanced a trc dominant negative phenotype. In both flies and yeast, these genes seem to act in the same pathway because double null mutants have the same phenotype as each single mutant (Cong et al., 2001; Hirata et al., 2002; Nelson et al., 2003).

In S. cerevisiae, Cbk1 is found in both the nucleus and cytoplasm, whereas Tao3 is only cytoplasmic. Our data indicate that these proteins behave differently in the fly system. In pupal wing cells, we did not see any evidence for the nuclear accumulation of either Trc or Fry. Interestingly, both proteins accumulated in growing hairs where they seemed to be associated with vesicles or particles. This suggests the possibility that these proteins function to regulate or direct intracellular transport in growing hairs. In other cells types (e.g., salivary gland cells), we saw evidence for both nuclear and cytoplasmic accumulation of both Trc and Fry; hence, the subcellular localization of these two proteins is subject to cell type-specific regulation. There are a number of animal cell types where trc and fry function in the morphogenesis of polarized cell extensions (Zallen et al., 2000; Cong et al., 2001; Emoto et al., 2004). Our finding that Trc and Fry accumulate in wing hairs suggests that that these proteins function locally within the cellular extension to regulate its outgrowth.

In both the yeast systems and in our experiments, Trc and Fry (and their yeast homologues) influenced the subcellular localization of the other, although at least superficially there seem to be substantial differences. We found decreased accumulation of Trc in hairs in fry mutant cells, suggesting the possibility that Fry serves to recruit Trc to the hair. In contrast, in S. cerevisiae Tao3 mutants did not alter the bud neck accumulation of Cbk1 as would be expected if Tao3 helped recruit Cbk1 to the neck. Instead, in a Tao3 mutant the restriction of Cbk1 to the daughter cell nucleus was lost. Thus, it is not clear whether the mechanism used by Fry/Tao3 to regulate Trc/Cbk1 localization is conserved. However, given that differences are seen in the subcellular localization of Trc and Fry in different tissues in Drosophila it is perhaps not surprising that differences are seen between yeast and fly. We found increased accumulation of Fry in hairs in trc mutant cells, suggesting that Trc activity negatively regulated Fry recruitment to the hair. This is reminiscent of the finding in yeast that the amount of Tao3 in the bud neck increased slightly in Cbk1 mutants, which was taken as evidence of a feedback system linked to Cbk1 activity governing the accumulation of Cbk1/Tao3 at the bud neck (Nelson et al., 2003). However, both of these results are different from the decrease in polarized Mor2 accumulation in orb6 mutants in S. pombe (Hirata et al., 2002). Together, these results suggest that an interaction between trc and fry (and their homologues) is conserved over a wide phylogenetic range but that the interaction is modified in organism-, cell-, and development-specific ways.

Trc and Fry Function before and during Hair Morphogenesis

Previous observations showed that mutations in trc and fry caused cells to form ectopic wing hairs, implying that these genes functioned before hair initiation (Geng et al., 2000; Cong et al., 2001). Time-lapse observations on developing arista laterals in fry and trc mutants showed the ectopic initiation of laterals and the splitting of laterals at a variety of developmental stages (Cong et al., 2001; He and Adler, 2001). These observations indicate that trc and fry act before lateral initiation and suggest they continued to function during the 18 h or so of lateral outgrowth (He and Adler, 2001). Several results described in this article argue that trc and fry function for a long period in wing hair differentiation. Before hair morphogenesis, we found that trc and fry cells had a greater than normal cross section and were less regular in shape. In addition, the level of F-actin below the apical membrane was often increased in mutant cells. These observations indicate that trc and fry function before hair initiation. We also observed both Trc and Fry protein in developing hairs and their accumulation there was sensitive to trc and fry function, consistent with these proteins functioning during the process of hair elongation. The reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton is response to Trc and Fry is reminiscent of observations in S. pombe, where Mor2 is important for the localization of F-actin at the cell end(s) (Hirata et al., 2002).

The observation that Trc accumulation in the growing hair is sharply reduced in phosphorylation site mutants suggests that the activity of Trc is related to its subcellular location. It is possible that the action of an upstream kinase plays a role in regulating Trc location and activity. We found that a lack of Trc function, either from a mutation in the endogenous trc gene or from the directed expression of a dominant negative protein increased the accumulation of Fry in the growing hair. We hypothesize that Fry in the hair acts as a scaffold and recruits Trc to the hair (Figure 7). Trc in the hair would function to both phosphorylate substrates in regulating polarized growth and to limit the further recruitment of Fry to the hair. Such a feedback system could regulate both the activity and accumulation of these proteins in the hair.

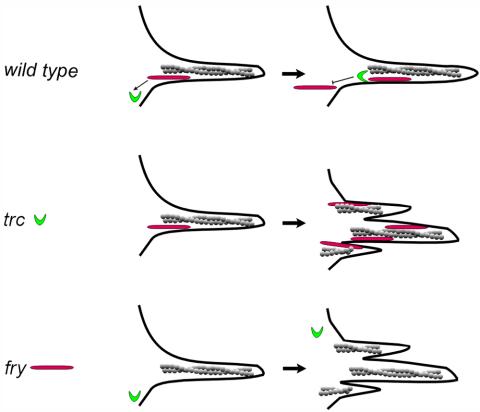

Figure 7.

Model for Trc and Fry interacting during hair Development. A cartoon of a developing hair is shown. Trc is in green, Fry in red, and actin in gray. In wild-type, Fry is recruited to the hair and it in turn recruits Trc. Trc activity locally inhibits further recruitment of Fry. This feedback mechanism ensures the proper level of these proteins in the hair. In the trc mutant, excess Fry is recruited to the hair due to the lack of the Trc-based negative feedback. Due to a lack of Trc activity hair morphogenesis is also abnormal. In the fry mutant, Fry protein is not present to be recruited to the hair, and this in turn results in decreased recruitment of Trc. The lack of Trc activity results in abnormal hair development.

In all subcellular locations, both Trc and Fry were found in a punctuate pattern. This raises the possibility that Trc and Fry might be present in vesicles or other intracellular transport organelles. These putative vesicles did not stain for F-actin. The growth of polarized structures such as hairs, bristles, laterals, or dendrites requires the directed transport of cellular components from the central cytoplasm to the growing extension. To form a multiple hair cell requires that the cell transport material to several instead of a single growing hair. We suggest that Trc and Fry function to maintain hair integrity by regulating the transport of hairforming components to a single targeted location on the apical surface. Wing cells begin to secrete large amounts of cuticulin early in the process of hair outgrowth (Wong and Adler, 1993). This raises the possibility that Trc and Fry could be present on secretory vesicles; however, it is not clear how to connect a defect in the deposition of cuticulin with the extreme multiple hair cell phenotype seen in trc and fry cells.

Trc and Fry Are Likely Part of a Conserved Signaling Complex

In S. cerevisae, Cbk1 and Tao3 are part of the RAM pathway (Nelson et al., 2003). Another essential component of this pathway is Mob2p, which is known to bind to Cbk1p and to be important for Cbk1 activity (Colman-Lerner et al., 2001; Weiss et al., 2002; Nelson et al., 2003). Mutants of Cbk1, Tao3, and Mob2 share the same phenotype (Nelson et al., 2003). The related Dbf2 kinase and Mob1 function together as part of the mitotic exit network. Recently, evidence for an activating interaction between mammalian Ndr and Mob proteins was reported (Bichsel et al., 2004; Devroe et al., 2004). Given this conservation, it seems likely that Trc also will interact with a Mob.

There are four Mob-like proteins encoded by the Drosophila genome (CG13852, CG4946, CG11711, and CG3403). A recent genomics scale two-hybrid screen of Drosophila proteins reported an interaction between Trc and CG13852. Further studies will be required to confirm this and to determine whether any of the other Dmob proteins can bind to Trc. The Drosophila warts/lats gene encodes a kinase that is related to the Ndr group, and it is also a candidate for binding to one or more of the fly Mob proteins.

Wing Hair Integrity Requires Both Trc/Fry, Rho1/Drok, and Dral/JNK Signaling

Drosophila wing hair development requires restriction of the initiation site to the apical-distal corner and the activation of actin assembly so that a single hair is formed (Turner and Adler, 1998; Winter et al., 2001). The Fz/Dsh planar cell polarity pathway has been shown to regulate the initiation site and hence the orientation of the hair (Wong and Adler, 1993). Rho1 and Drok activity regulates the number of hairs without affecting their orientation (Strutt et al., 1997; Winter et al., 2001). We provided evidence for a positive genetic interaction between Trc/Fry and Rho1/Drok. Drok is thought to regulate the cytoskeleton in a rather direct manner by phosphorylating Spaghetti Squash (Sqh) (Drosophila nonmuscle myosin regulatory light chain); thus, Trc is not likely to function downstream of Drok. It seems likely that Trc functions either upstream of Rho1/Drok or in parallel. Trc has been found to be upstream of and to negatively regulate DRac in sensory neurons (Emoto et al., 2004). Thus, Trc functioning upstream of Rho1/Drok seems feasible. However, we also found evidence for Trc interacting with other small GTPases, such as Drac1, Dcdc42, and Dral. It is possible that Trc is upstream of all of these, but we prefer the hypothesis that the proteins encoded by these genes function either in parallel or in a network that regulates the cytoskeleton.

The interaction between Trc/Fry and Dral was very strong. Dral has been implicated in regulating a number of different cellular processes (Feig, 2003). One of these is vesicle trafficking. We find this intriguing given our finding that Trc and Fry are found in a punctuate pattern in wing hairs as if they are attached to vesicles or particles. It seems possible that the interaction between Dral and Trc/Fry could be functioning at this level.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Bloomington Stock Center for fly stocks. We thank Brian Hemmings and Marlo Stegert for providing the human NDR cDNA and for sharing information. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants GM-53498 (to P.N.A.) and R0-1NS40929 (to J.Y.N.). K. E. is a research associate and J.Y.N is an investigator of Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Article published online ahead of print in MBC in Press on December 9, 2004 (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E04-09-0828).

The online version of this article contains supplemental material at MBC Online (http://www.molbiolcell.org).

References

- Bhattacharya, S., Large, E., Heizmann, C. W., Hemmings, B., and Chazin, W. J. (2003). Structure of the Ca2+/S100B/NDR1 kinase peptide complex: insights into S100 target specificity and activation of the kinase. Biochemistry 42, 14416-14426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bichsel, S. J., Tamaskovic, R., Stegert, M. R., and Hemmings, B. A. (2004). Mechanism of activation of nuclear Dbf2-related (NDR) kinase by the hMOB1 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 35228-35235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidlingmaier, S., Weiss, E. L., Seidel, C., Drubin, D. G., and Snyder, M. (2001). The Cbk1p pathway is important for polarized cell growth and cell separation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 2449-2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand, A. H., and Perrimon, N. (1993). Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 118, 401-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colman-Lerner, A., Chin, T. E., and Brent, R. (2001). Yeast Cbk1 and Mob2 activate daughter-specific genetic programs to induce asymmetric cell fates. Cell 107, 739-750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong, J., Geng, W., He, B., Liu, J., Charlton, J., and Adler, P. N. (2001). The furry gene of Drosophila is important for maintaining the integrity of cellular extensions during morphogenesis. Development 128, 2793-2802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devroe, E., Erdjument-Bromage, H., Tempst, P., and Silver, P. A. (2004). Human Mob proteins regulate the NDR1 and NDR2 serine-threonine kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 24444-24451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du, L. L., and Novick, P. (2002). Pag1p, a novel protein associated with protein kinase Cbk1p, is required for cell morphogenesis and proliferation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 503-514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton, S., Wepf, R., and Simons, K. (1996). Roles for Rac1 and Cdc42 in planar polarization and hair outgrowth in the wing of Drosophila. J Cell. Biol. 135, 1277-1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emoto, K., He, Y., Ye, B., Grueber, W. B., Adler, P. N., Jan, L. Y., and Jan, Y. N. (2004). Control of dendritic branching and tiling by the tricornered-kinase/furry signaling pathway in Drosophila sensory neurons. Cell 119, 245-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feig, L. A. (2003). Ral-GTPases: approaching their 15 minutes of fame. Trends Cell Biol. 13, 419-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng, W., He, B., Wang, M., and Adler, P. N. (2000). The tricornered gene, which is required for the integrity of epidermal cell extensions, encodes the Drosophila nuclear DBF2-related kinase. Genetics 156, 1817-1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakeda-Suzuki, S., Ng, J., Tzu, J., Dietzl, G., Sun, Y., Harms, M., Nardine, T., Luo, L., and Dickson, B. J. (2002). Rac function and regulation during Drosophila development. Nature 416, 438-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanks, S. K., and Hunter, T. (1995). The eukaryotic protein kinase superfamily: kinase (catalytic) domain structure and classification. FASEB J. 9, 576-596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, B., and Adler, P. N. (2001). Cellular mechanisms in the development of the Drosophila arista. Mech. Dev. 104, 69-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hing, H., Xiao, J., Harden, N., Lim, L., and Zipursky, S. L. (1999). Pak functions downstream of Dock to regulate photoreceptor axon guidance in Drosophila. Cell 97, 853-863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata, D., et al. (2002). Fission yeast Mor2/Cps12, a protein similar to Drosophila Furry, is essential for cell morphogenesis and its mutation induces Wee1-depdendent G(2) delay. EMBO J. 21, 4863-4874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mah, A. S., Jang, J., and Deshaies, R. J. (2001). Protein kinase Cdc15 activates the Dbf2-Mob1 kinase complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 7325-7330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millward, T. A., Cron, P., and Hemmings, B. A. (1995). Molecular cloning and characterization of a conserved nuclear serine (threonine) protein kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 5022-5026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millward, T. A., Hess, D., and Hemmings, B. A. (1999). Ndr1 protein kinase is regulated by phosphorylation on two conserved sequence motifs. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 33847-33850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, B., et al. (2003). RAM: a conserved signaling network that regulates Ace2p transcriptional activity and polarized morphogenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 3782-3803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa, R., Nagata-Ohashi, K., Takeichi m., Mizuno, K., and Uemura, T. (2002). Control of actin reorganization by Slingshot, a family of phosphatases that dephosphorylate ADF/cofilin. Cell. 108, 233-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racki, W. J., Becam, A. M., Nasr, F., and Herbert, C. J. (2000). Cbk1p, a protein similar to the human myotonic dystrophy kinase, is essential for normal morphogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 19, 4524-4532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawamoto, K., Winge, P., Koyama, S., Hirota, Y., Yamada, C., Miyao, S., Yoshikawa, S., Jin, M. H., Kikuchi, A., and Okano, H. (1999). The Drosophila Ral GTPase regulates developmental cell shape changes through the Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase pathway. J. Cell Biol. 146, 361-372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stegert, M. R., Tamaskovic, R., Bichsel, S. J., Hergovich, A., and Hemmings, B. A. (2004). Regulation of NDR2 protein kinase by multi-site phosphorylation and the S100B calcium-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 23806-23812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strutt, D. I., Weber, U., and Mlodzik, M. (1997). The role of RhoA is tissue polarity and Frizzled signaling. Nature 387, 292-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaskovic, R., Bichsel, S. J., and Hemmings, B. A. (2003a). NDR family of AGC kinases-essential regulators of the cell cycle and morphogenesis. FEBS Lett. 546, 73-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaskovic, R., Bichsel, S. J., Rogniaux, H., Stegert, M. R., and Hemmings, B. A. (2003b). Mechanism of Ca2+-mediated regulation of NDR1 protein kinase through autophosphorylation and phosphorylation by an upstream kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 6710-6718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner, C. M., and Adler, P. N. (1998). Distinct roles for the actin and microtubule cytoskeletons in the morphogenesis of epidermal hairs in Drosophila. Mech. Dev. 70, 181-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verde, F., Wiley, D. J., and Nurse, P. (1998). Fission yeast orb6, a ser/thr protein kinase related to mammalian rho kinase and myotonic dystrophy kinase is required for maintenance of cell polarity and coordinates cell morphogenesis with the cell cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 7526-7531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, E. L., Kurischko, C., Zhang, C., Shokat, K., Drubin, D. G., and Luca, F. C. (2002). The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mob2p-Cbk1p kinase complex promotes polarized growth and acts with the mitotic exit network to facilitate daughter cell-specific localization of Ace2p transcription factor. J. Cell Biol. 158, 885-900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter, C. G., Wang, B., Ballew, A., Royou, A., Karess, R., Axelrod, J. D., and Luo, L. (2001). Drosophila Rho-associated kinase (Drok) links Frizzled-mediated planar cell polarity signaling to the actin cytoskeleton. Cell 105, 81-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong, L. L., and Adler, P. N. (1993). Tissue polarity genes of Drosophila regulate the subcellular location for prehair initiation in pupal wing cells. J. Cell Biol. 123, 209-221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, T., and Rubin, G. M. (1993). Analysis of genetic mosaics in developing and adult Drosophila tissues. Development 117, 1223-1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young, P. E., Richman, A. M., Ketchum, A. S., and Kiehart, D. P. (1993). Morphogenesis in Drosophila requires nonmuscle myosin heavy chain function. Genes Dev. 7, 29-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zallen, J. A., Peckol, E. L., Tobin, D. M., and Bargmann, C. I. (2000). Neuronal cell shape and neurite initiation are regulated by the Ndr1 kinase SAX-1, a member of the Orb6/COT-1/warts serine/threonine kinase family. Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 3177-3190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.