Abstract

Introduction:

Few studies have dealt with the potential correlation between anxiety, depression, and cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older adults.

Method:

This longitudinal study was conducted in the city of Montreal, Canada, with 352 older adults aged 55 years or more. The participants were interviewed at baseline and again 2 years later. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) score was estimated and compared between the 2 time points, the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) was used to assess major depression and anxiety, and the K10 measured high psychological distress. Likewise, major depression, anxiety disorders, and psychological distress were evaluated at the 2 study time points.

Results:

In older adults with a diagnosis of depression or anxiety at baseline, no significant reduction in the MoCA score indicating deterioration in cognitive function was found 2 years later. Nevertheless, in individuals with a high level of psychological distress at baseline, there was a significant reduction in MoCA scores 2 years later, indicating deterioration in cognition. The findings of the present study suggest that a high level of psychological distress in addition to environmental factors may constitute important predictors for cognitive health.

Keywords: depression, anxiety, cognitive impairment, psychological distress, environmental factors

Abstract

Introduction:

Peu d’études se sont penchées sur la corrélation potentielle entre l’anxiété la dépression et la déficience cognitive chez les adultes âgés qui résident dans la communauté.

Méthode:

Cette étude longitudinale a été menée dans la ville de Montréal, Canada, auprès de 352 adultes âgés de 55 ans et plus. Les participants ont été interviewés au départ puis deux ans plus tard. Le score à l’Évaluation cognitive de Montréal (MoCA) a été estimé et comparé entre les deux temps de mesure, et Entrevue internationale de diagnostic composée (CIDI) a servi à évaluer la dépression majeure et l’anxiété alors que le K10 a mesuré la détresse psychologique élevée. La dépression majeure, les troubles anxieux et la détresse psychologique ont de même été évalués aux deux temps différents de l’étude.

Résultats:

Chez les adultes âgés ayant un diagnostic de dépression ou d’anxiété au départ, aucune réduction significative du score au MoCA indiquant une détérioration de la cognition n’a été observée deux ans plus tard. Néanmoins, chez les personnes ayant un taux élevé de détresse psychologique au départ, il y avait une réduction significative des scores au MoCA deux ans plus tard, indiquant une détérioration de la cognition. Les résultats de la présente étude suggèrent qu’un niveau élevé de détresse psychologique qui s’ajoute aux facteurs environnementaux peuvent constituer d’importants prédicteurs de la santé cognitive.

In a population, mental health results from complex interactions between different parameters at individual and population levels.1 Because mental health and well-being are the result of a balance between the risk factors to which the population is exposed and the protective factors at its disposal,2 depression has been associated with cognitive impairment in 2 different ways: depression as a risk factor for dementia3,4 and depression that leads to mild cognitive impairment as a result of a possible negative effect of mood symptoms on cognition.3,4 The assumptions on the increased risk of mild cognitive impairment in depressed individuals and their progression to dementia are conflicting.5,6 Discrepancies between studies may be related to different follow-up periods, different study designs, the characteristics of the samples, or differences in methodology.5,6

Most studies conducted to investigate the association between depression, anxiety, and cognitive impairment were performed with clinical populations,7 with few studies having investigated the potential association between anxiety, depression, and cognitive performance in community-dwelling older adults.2,3 States of anxiety and depression are common; nevertheless, it is not known whether these disorders lead to the occurrence of cognitive impairment or, assuming that mild cognitive impairment could be an initial stage of dementia, whether symptoms of depression and anxiety could constitute an early manifestation rather than a risk factor for dementias and Alzheimer disease.6,8–10 Hence, an underlying neuropathological condition would induce mild cognitive impairment or dementia, which in turn would also cause depressive symptoms.9–11 In this respect, depression, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia could constitute a possible clinical continuum.6,8–11 Neuropsychiatric symptoms may accompany predementia syndromes and help identify incipient dementia. In older adults, depression may be particularly associated with an increased risk for dementia.9

The objective of the present study was to longitudinally evaluate the potential correlation between anxiety, depression, and cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older adults. Establishing the correlation between these conditions could shed light on the primary cause and/or predict the outcome of patients affected by these dysfunctions.

Method

Study Setting and Sample

This longitudinal, population-based study was developed in the community. An area consisting of 4 districts of Montreal, Canada, in which the purchasing power of the population is lower than that of other districts in the city, was selected for the study. There are 269,720 residents in this area, which is divided into the following neighbourhoods: Saint-Henri/Pointe St-Charles, Lachine/Dorval, LaSalle, and Verdun. Of the residents, 195,585 were between 15 and 65 years of age. A representative sample of the population of this age group was randomly selected based on their home addresses. A total of 3408 addresses were selected for recruitment using a list supplied by the 2004 property tax evaluation register of the city of Montreal. To increase recruitment, the initial selection was expanded to include 14 homes that were direct, door-to-door neighbors to the original address. Therefore, 3408 addresses were originally selected, with the potential to reach a further 47,712 addresses. Only 1 person was selected and interviewed per household. The sample consisted of 2433 individuals, around 600 participants from each neighborhood, distributed as follows: Santi-Henri/Pointe St-Charles (612), Lachine/Dorval (603), LaSalle (584), and Verdun (635). The methods used for recruitment, for the interviewing process, and for taking measurements have already been described elsewhere.12,13

The present data were extracted from the baseline and second time point data sets of the Montreal Population-Based Epidemiological Study on Mental Health.12 Of the 2433 individuals interviewed at baseline (2007), 1823 were interviewed again 2 years later (2009). Loss to follow-up was 25.1% (n = 610) and consisted of 138 individuals (5.7%) who refused to participate, 230 (9.5%) who could not be located, 230 (9.5%) who had moved to an area outside that covered by the study, and 12 (0.5%) who had died. Loss to follow-up14,15 was greater among younger individuals, those with poorer education or socioeconomic levels, and those dependent on psychoactive substances. In the present final sample, 352 older adults (≥55 years of age) were interviewed at baseline (2007) and again 2 years later (2009). The 2-year follow-up rate among those aged 55 or more was 81.45%.

Instruments

Psychological distress was evaluated using the Kessler psychological distress scale (K10).16 This 10-question instrument assesses the frequencies of psychological distress in relation to the preceding month, rated according to a 5-point Likert scale. Although the K10 is widely used, there is no well-established cutoff point to determine a high degree of psychological distress. Using 2 approaches, Caron and Liu1 identified an optimal cutoff point of 9, with sensitivity of 47.9%, specificity of 91.7%, and an area under the curve of 0.836. Consequently, the cutoff point for the identification of a high degree of psychological distress was defined as 9.

The mental disorders identified using the short-form version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI)17 included mood disorders (major depression and mania) and anxiety disorders (panic attacks, social phobia, and agoraphobia). The level of agreement between the CIDI and the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision is generally good (κ coefficients: 0.58-0.97). Depending on the diagnosis, sensitivity was 0.43 to 1 and specificity was 0.84 to 0.99.12

Cognitive impairment in individuals over 55 years of age was measured using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) tool,18 which was designed to help primary care physicians detect mild cognitive impairment, a clinical state that often leads to dementia. MoCA detected in 90% of the individuals with mild cognitive impairment, confirming its high sensitivity and excellent specificity, which reached 87%.18

Coping strategies and stress management were evaluated using a questionnaire applied in the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS 1.2).19 The instrument is divided into 3 sections: the ability to handle stress, the principal sources of stress, and the frequency with which coping strategies are used. The internal consistency of the subscales ranged from 0.77 to 0.86 for the coping strategy indicator, 0.62 to 0.81 for Ways of Coping Revised, and 0.65-0.91 for the COPE scale.19

Perceptions on the neighborhood in which the individual lived were evaluated using various instruments. Disturbing elements were measured using the Neighborhood Disorder Scale, which consists of 9 units referring to problems such as garbage on the sidewalks, abandoned vehicles, graffiti, and drug traffickers (α = 0.84).20

Procedure

The internal review board of the Douglas Mental Health University Institute approved the project under number 06/33. The interviewers telephoned the residents who had previously agreed to participate in the study within a week of recruitment to schedule a face-to-face meeting, either in the participant’s home or in the Douglas Mental Health Hospital. At baseline, 305 of 352 patients were interviewed at home, 23 at the hospital or in one of the clinics or community medical centers, and 24 at other locations. At the second time point, 322 of 352 patients were interviewed at home; 17 at a hospital, clinic, or community medical center; and 13 at other locations. The interviews, which only began after the participant had signed an informed consent form, lasted approximately 1.5 to 3 hours.

Statistical Analysis

A correlation matrix, including all the potential predictors under consideration and the outcome variable, was produced and verified. No problems involving collinearity were identified. Simple linear regression was performed for assessing the raw associations between the continuous score of psychological distress, depression, anxiety at baseline, and the MoCA score at the 2-year time point. Hierarchical linear regression was conducted to model the overall MoCA score obtained at the second time point. The following baseline variables were considered potential predictors and were inserted sequentially into the model: a) overall MoCA score; b) sociodemographic variables, including age, sex, marital status, education level, and spoken language; c) employment status over the past 12 months; d) social support; e) perception of safety in the neighborhood; f) ability to cope with unexpected and difficult problems; g) continuous score of psychological distress; and h) major depression over the preceding 12 months. The model was constructed using all the potential predictors at baseline from a) to h).

Impaired cognition could be related to attrition. Therefore, to avoid biased results due to differential attrition, the inverse probability of attrition weights (IPAWs)21 method was used in all the regression analyses. Sociodemographic and clinical variables, including age, sex, ethnicity, education, alcohol consumption, self-perception of health, and overall MoCA score at baseline, were included in the model to calculate the probability of attrition.

The overall MoCA score at baseline was included as an independent variable, while that at the 2-year time point was used as a dependent variable. The model was constructed to investigate the baseline variables that were predictive of change in the overall MoCA score at the second time point, over the 2-year interim period.

Path analysis was conducted to assess the cross effects of mental disorder status and cognitive performance. Specifically, the following points were evaluated: 1) whether current mental disorder status predicts future cognitive performance and 2) whether current cognitive performance predicts future mental disorder status. Three separate variables were used to represent mental disorder status: overall score for psychological distress over the preceding month (K10), diagnosis of an episode of major depression in the preceding 12 months (yes/no), and diagnosis of anxiety disorder in the preceding 12 months (yes/no).

Different cognitive domains were evaluated at the 2-year time point, taking depression, anxiety, and a high level of psychological distress as predictors. P values were calculated using the Wilcoxon 2-sample test.

Data analysis was conducted using the SAS software program, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Significance level was defined as 0.05 in all tests.

Results

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the 352 participants older than 55 years. Mean ± SD age was 60 ± 3.16 years. Overall, 65.9% of the participants were women. Regarding marital status, 18% of the individuals were single; 40% were separated, widowed, or divorced; and 42% were married or in a stable union. Regarding education, 68.5% of the participants had university degrees. Sixty-one percent of the sample consisted of French speakers.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Participants at Baseline (n = 352).

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, y (mean, SD) | 59.76 (3.16) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 232 (65.91) |

| Male | 120 (34.09) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Single | 64 (18.18) |

| Married | 111 (31.53) |

| In a stable union | 37 (10.51) |

| Separated/widowed/divorced | 140 (39.77) |

| Education level, n (%) | |

| Elementary school | 62 (17.61) |

| High school | 49 (13.92) |

| College/university | 241 (68.47) |

| Spoken language, n (%) | |

| English | 85 (24.22) |

| French | 213 (60.68) |

| English + French | 21 (5.98) |

| Other | 32 (9.12) |

| Immigrant, n (%) | |

| Yes | 65 (18.47) |

| No | 287 (81.53) |

| Employed in the preceding 12 months, n (%) | |

| Yes | 220 (62.50) |

| No | 132 (37.50) |

| Household income (≥1000 dollars), mean (SD) | 56.05 (50.92) |

| Personal income (≥1000 dollars), mean (SD) | 35.06 (28.88) |

Note: Numbers may not add up to the total sample population due to missing values.

Overall, 60% and 63% of the individuals had no cognitive impairment at baseline or at 2 years, respectively. In relation to depression, 7.1% had major depressive disorder at both time points. The frequency of anxiety disorders (panic attacks, social phobia, and agoraphobia) was 5.3% at baseline and 3% at 2 years, while a high level of psychological distress was identified in 33.5% of the individuals at baseline and in 36% at 2 years.

Simple linear regression showed that higher psychological distress in the preceding month (β = –1.10; P < 0.0001) and major depression in the preceding 12 months (β = –1.45; P = 0.025) were factors predictive of cognitive decline at the second time point; however, anxiety disorders were not (β = –0.08; P = 0.90) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Bivariate Association with Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) Score 2 Years Later (n = 352).a

| Potential Predictors at Baseline | Parameter Estimate | Standard Error | t Value | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous score of psychological distress | –1.10 | 0.02 | –4.26 | <0.0001 |

| Major depressive disorder | –1.45 | 0.65 | –2.25 | 0.0252 |

| Anxiety disorder | 0.09 | 0.74 | 0.12 | 0.9042 |

aResults are from simple linear regression models designed to test the bivariate associations between each of the potential predictors and total MoCA score 2 years later.

Neither psychological distress nor major depression in the preceding 12 months remained significant following adjustment for selected sociodemographic, psychosocial, and neighborhood variables.

Multiple linear regression showed that the baseline MoCA score was the most important predictor of performance in the MoCA scale 2 years later (P < 0.0001, with this factor explaining 34.96% of the variance in the outcome variable). A higher perception of insecurity in the individual’s neighborhood, not being a fluent French speaker, and being married/in a stable relationship were variables that were associated with lower MoCA scores at 2 years (P = 0.0018, P = 0.0052, and P = 0.0027, respectively; these factors explained 2.03%, 0.85%, and 2.16% of the variance in the outcome variable, respectively). Having a university degree and being able to cope well with unexpected and difficult problems constituted protective factors (P = 0.0174 and P = 0.044, respectively, explaining 2.13% and 1.03%, respectively, of the variance in the outcome variable) and were negatively associated with low MoCA scores at the 2-year time point. On the other hand, age, social support, and having been employed in the preceding year were not significant predictors of MoCA scores at 2 years (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multiple Linear Regression Model for Predicting Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) Score at the 2-Year Evaluation (n = 352).

| Potential Predictors at Baseline | Parameter Estimate | 95% Confidence Interval | t Value | P Value | Variance Explained (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |||||

| Overall MoCA score | 0.52 | 0.44 | 0.61 | 12.26 | <0.0001 | 34.96 |

| Age | 0.02 | –0.07 | 0.10 | 0.39 | 0.6988 | 0.00 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female (reference) | ||||||

| Male | –0.44 | –1.02 | 0.14 | –1.49 | 0.1374 | 0.02 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married/in a stable union | –0.34 | –0.56 | –0.12 | –3.02 | 0.0027 | 2.16 |

| All others (reference) | ||||||

| Education level | ||||||

| Elementary school (reference) | ||||||

| High school | 0.75 | –0.27 | 1.78 | 1.44 | 0.1497 | 0.05 |

| College/university | 0.96 | 0.17 | 1.75 | 2.39 | 0.0174 | 2.13 |

| Spoken language | ||||||

| French (reference) | ||||||

| Others | –0.80 | –1.35 | –0.24 | –2.81 | 0.0052 | 0.85 |

| Employed in the past 12 months | 0.25 | –0.31 | 0.82 | 0.89 | 0.3756 | 0.55 |

| Social support total score | 0.00 | –0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.9739 | 0.43 |

| Neighborhood insecurity score | –0.33 | –0.54 | –0.13 | –3.14 | 0.0018 | 2.03 |

| Ability to cope with unexpected and difficult problems: good vs. poor | 1.03 | 0.03 | 2.03 | 2.02 | 0.0440 | 1.03 |

| Major depression episode in the past 12 months | 0.21 | –0.89 | 1.31 | 0.37 | 0.7130 | 0.02 |

| Psychological distress score | –0.03 | –0.07 | 0.02 | –1.02 | 0.3067 | 0.15 |

Note: In total, the model explains 44.38% of variance in the overall MoCA score at 2 years.

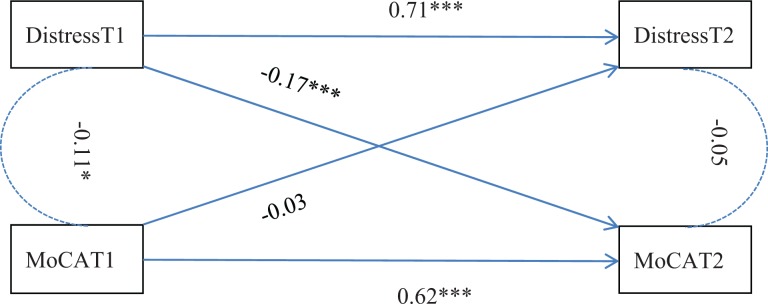

Figure 1 shows the path analysis model using the preceding-month psychological distress for mental disorder status. Standardised path coefficient and correlation coefficient are shown for each assessed effect and correlation, respectively. Preceding-month psychological distress had a significant negative effect on the future overall MoCA score (standardised path coefficient = –0.17), indicating that higher psychological distress leads to poorer cognitive performance in the future. Overall MoCA score had no effect on future psychological distress.

Figure 1.

The cross-effects of overall Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) score and preceding-month psychological distress. T1 = baseline. T2 = Two-year time point. Distress = preceding-month psychological distress store. *0.01 < P < 0.05. **0.001 < P < 0.01. ***P < 0.001.

Path analysis models for a diagnosis of major depressive episode or anxiety disorder in the preceding 12 months were performed separately. Neither of these models identified statistically significant predictive effects either of mental disorder status on the overall MoCA score or of the overall MoCA score on mental disorder status.

When the different cognitive domains were evaluated at the 2-year time point, taking depression, anxiety, and a high level of psychological distress as predictors, the visuospatial/executive domain was significantly affected by a high degree of psychological distress, and there was also a tendency towards an effect induced by depression (Table 4). There was a tendency towards an effect on attention induced by a high level of psychological distress.

Table 4.

Mean Scores for the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) Scale Domains at the 2-Year Time Point for Participants with Different Disorders at Baseline.

| MoCA Domain Scores at 2 Years | Disorders Detected at Baseline | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major Depressive Disorder | Anxiety Disorder | High Level of Psychological Distress | |||||||

| Yes (n = 13) | No (n = 204) | P Value | Yes (n = 13) | No (n = 204) | P Value | Yes (n = 65) | No (n = 157) | P Value | |

| Visuospatial/executive | 3.92 | 4.40 | 0.095 | 4.31 | 4.37 | 0.85 | 4.11 | 4.47 | 0.0031 |

| Naming | 2.92 | 2.91 | 0.92 | 3.00 | 2.91 | 0.33 | 2.94 | 2.90 | 0.42 |

| Attention | 5.61 | 5.41 | 0.74 | 5.46 | 5.42 | 0.68 | 5.32 | 5.46 | 0.093 |

| Language | 2.46 | 2.64 | 0.42 | 2.54 | 2.64 | 0.53 | 2.62 | 2.64 | 0.78 |

| Abstraction | 1.62 | 1.67 | 0.77 | 1.46 | 1.67 | 0.15 | 1.60 | 1.69 | 0.23 |

| Delayed recall | 3.92 | 4.25 | 0.40 | 4.31 | 4.23 | 1.00 | 3.97 | 4.32 | 0.11 |

| Orientation | 5.85 | 5.91 | 0.24 | 6.00 | 5.91 | 0.31 | 5.86 | 5.92 | 0.26 |

Note: Subjects with cognitive impairment at baseline were excluded from the analysis. P values were calculated using the Wilcoxon 2-sample test.

Discussion

Psychological distress and depression, but not anxiety, were found to predict cognitive decline according to a simple linear regression between the continuous score of psychological distress, depression, anxiety, and the MoCA score after 2 years. When psychological distress and depression were introduced separately into a multiple linear regression model, controlled for other variables, statistical significance was lost, suggesting that the other variables are associated with depression and psychological distress and have more power to explain cognitive decline. In older adults with a diagnosis of depression or anxiety at baseline, no significant decline was found in cognition (no significant reduction in MoCA score) 2 years later when assessed using multiple linear regression and path analysis. However, in individuals with a high level of psychological distress at baseline, cognition deteriorated, as shown by a significant reduction in MoCA score at 2 years, assessed using simple linear regression and path analysis.

The difference in the results between the multiple linear regression and the cross-lagged panel data analysis can be explained as follows: 1) the 2 analyses serve different purposes. Multiple linear regression was used to assess the independent effect of psychological distress/depression on cognitive decline, whereas the cross-lagged panel data analysis evaluated how psychological distress and cognitive decline affect each other. 2) The former analysis was adjusted for some covariates, whereas no adjustments were made in the latter.

When the different cognitive domains were evaluated at 2 years, taking depression, anxiety, and a high level of psychological distress into consideration as predictors, the visuospatial/executive domain was found to be significantly affected by a high level of psychological distress, and there was a tendency towards an effect of depression as well. There was also a tendency towards an effect of a high level of psychological distress on attention.

Gale et al.2 conducted a longitudinal, population-based study in England to evaluate the association between symptoms of depression and cognitive ability in the elderly. Impairment of the principal cognitive functions occurred due to age, particularly from 60 years of age onwards; however, the progression of depressive symptoms did not tend to intensify with age, and there was a weak association between depressive symptoms and cognitive impairment in the patients in the 60- to 80-year age group. There was no consistent evidence that the severity of the depressive state led to greater cognitive impairment, and the hypothesis that cognitive impairment negatively affects depressive states was not confirmed.

In a cross-sectional, population-based study with 102 individuals aged 60 to 80 years, Beaudreau and O’Hara3 evaluated the association between symptoms of anxiety and depression and cognitive function. Those authors concluded that symptoms of depression in the absence of anxiety were not associated with cognitive decline. Wetherell et al.22 studied the association between anxiety and cognition in a sample of 704 healthy older adults. In the initial evaluation, a higher state of anxiety was associated with poorer memory, while greater neuroticism was associated with poorer visual recognition memory. Nevertheless, neither anxiety nor neuroticism was found to predict cognitive decline in that study.

Longitudinal studies have shown a strong association between subjective complaints of memory and the later development of dementia or cognitive decline over periods of 1 to 7 years. Paradise et al.23 identified a strong association between psychological stress and subjective complaints of memory, suggesting that strategies that reduce or prevent psychological stress can modify the risk of cognitive decline. In the present study, individuals with a high level of psychological distress at baseline were found to have a significant reduction in cognition 2 years later. Having a state of depression or anxiety did not represent a risk of poorer cognitive performance in community-dwelling older adults; however, psychological distress did. The psychiatric diagnoses of mood disorders evaluated here lead us to believe that risk factors for cognitive impairment other than anxiety and depression are present in community-dwelling older adults.

The MoCA score at baseline was the most important predictor of performance 2 years later (P < 0.0001). In individuals with a university education, the reduction in overall MoCA score found at the 2-year time point was lower (i.e., having a university degree acted as a protective factor). As shown by Anstey and Christensen,24 a better education level protects against cognitive decline. Nevertheless, some studies contradict this hypothesis and support the idea that education and vocabulary knowledge, as markers of cognitive reserve, are not associated with lower rates of age-associated decline in functioning, particularly regarding indexing reasoning and speed.25

The individuals whose perception of insecurity in their neighborhood was higher suffered a greater reduction in overall MoCA score. No previous studies evaluating the effect of self-reported safety in the neighborhood on cognitive performance were detected. However, it seems logical that with the decline of physical strength with age and the increased presence of health problems, insecurity in a neighborhood can be a major source of stress. Daily stressors are common and have been associated with poorer cognitive performance in older adults. Rickenbach et al.26 suggested that patients with mild cognitive impairment are less resilient when faced with daily stressors compared to older adults with no cognitive impairment. Rickenbach et al.27 also showed that individuals with greater cognitive decline reported greater levels of daily stress. These data support the hypothesis that environmental stressors and psychological distress exert a negative effect on cognition. Being able to cope well with stress was associated with a lesser decline in the overall MoCA score. Individuals who reported being able to cope better with unexpected and difficult problems had less of a reduction in their overall MoCA score compared to those who reported poor stress management skills. Learning to deal with frustrations and stress may protect against the effects of stress on health. Psychological characteristics may modulate the way in which the individual perceives and responds to stressful experiences. When the different cognitive domains were evaluated at 2 years, the visuospatial/executive domain was found to be significantly affected by a high level of psychological distress, and there was a tendency towards an effect of depression as well. These findings establish a link between depression and psychological distress and executive dysfunction, and they reinforce the finding that being able to cope constitutes a protective factor for cognition. Albanese et al.28 published a cohort study involving black and white males and females followed up from early adulthood to middle age and showed that individuals with poorer coping skills at baseline performed more poorly in cognitive tests 25 years later, irrespective of sociodemographic characteristics, cumulative cardiovascular risk factors, depressive symptoms, or cognitive ability at baseline.

The present findings suggest that a high level of psychological stress and perception of a lack of safety in the individual’s neighborhood may be important factors for cognitive health. Therefore, training in coping strategies may work as a protective factor on cognition. Public health policies able to promote better living conditions and improve neighborhood safety may protect individuals from high levels of stress. Feeling safe in the neighborhood in which one lives appears to represent a protective factor for cognitive function. In this context, poor health resulting from states of anxiety or depression may be less important for cognition than environmental issues and questions of defense in adverse situations.

This sample population comes from 4 districts in which the socioeconomic status of residents is generally lower than that of residents of other districts in the city, representing a possible limitation of this study. It is also possible that the insecurity of the neighborhood is a more pronounced element of stress in poorer neighborhoods; hence, these results cannot be generalised to more affluent neighborhoods. Additionally, these individuals were followed up for only 2 years, whereas a longer follow-up could provide more robust information on the cognitive health of these individuals. Although this study measured several anxiety disorders (panic attacks, social phobia, and agoraphobia) and found no links with cognitive functioning, it is impossible to confirm that this lack of relationship applies to other anxiety disorders such as generalised anxiety and specific phobias. Further studies will need to be carried out to clarify these points. Although a diagnosis of depression did not predict future cognitive impairment, the individual’s psychological distress score did. This discrepancy between depression, anxiety, and high psychological distress might be due to the sample size since few participants reported a diagnosis of depression or an anxiety disorder. The study adopted a cross-lagged panel design with which to assess the effects of psychological distress and MoCA on each other. In this case, if the stability of the model constructs is somewhat of a trait-like, time-invariant nature, the results will be limited insofar as making conclusions regarding causal influence is concerned. Therefore, we refrain from discussing evidence of any causal influence and limit our interpretation of the results to the confines of an exploratory analysis alone.

Conclusions

This is the first longitudinal study to assess the relationships between depression, anxiety, psychological distress, and cognitive impairment in a general population while controlling for numerous other variables. No significant association was found between depression and several anxiety disorders and the decline of cognitive function in individuals older than 55 years. However, the presence of high psychological distress 2 years previously and perception of insecurity in the individual’s neighborhood are factors that appear to predict deterioration in cognitive function. Having a higher education level and better coping abilities are protective factors.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the individuals who participated in the study.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The Canadian Institute of Health Research Funded the Study under reference CTP-79839.

References

- 1. Caron J, Liu A. A descriptive study of the prevalence of psychological distress and mental disorders in the Canadian population: comparison between low-income and non-low-income populations. Chronic Dis Can. 2010;30(3):84–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gale CR, Allerhand M, Deary IJ; HALCyon Study Team. Is there a bidirectional relationship between depressive symptoms and cognitive ability in older people? A prospective study using the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Psychol Med. 2012;42(10):2057–2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beaudreau SA, O’Hara R. The association of anxiety and depressive symptoms with cognitive performance in community-dwelling older adults. Psychol Aging. 2009;24(2):507–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Salthouse TA. Reduced processing resources. In: Salthouse TA, editor. Theoretical perspectives on cognitive aging Hillsdale (NJ: ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1991. p 301–348. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beaudreau SA, O’Hara R. Late-life anxiety and cognitive impairment: a review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(10):790–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sinoff G, Werner P. Anxiety disorder and accompanying subjective memory loss in the elderly as a predictor of future cognitive decline. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18(10):951–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dotson VM, Beydoun MA, Zonderman AB. Recurrent depressive symptoms and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment. Neurology 2010;75(1):27–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. DeLuca AK, Lenze EJ, Mulsant BH, et al. Comorbid anxiety disorder in late life depression: association with memory decline over four years. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(9):848–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Panza F, Frisardi V, Capurso C, et al. Late-life depression, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia: possible continuum? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(2):98–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gulpers B, Ramakers I, Hamel R, et al. Anxiety as a predictor for cognitive decline and dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;24(10):823–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ismail Z, Smith EE, Geda Y, et al. ; ISTAART Neuropsychiatric Symptoms Professional Interest Area. Neuropsychiatric symptoms as early manifestations of emergent dementia: provisional diagnostic criteria for mild behavioural impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(2):195–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Caron J, Fleury MJ, Perreault M, et al. Prevalence of psychological distress and mental disorders, and use of mental health services in the epidemiological catchment area of Montreal South-West. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fleury MJ, Ngui AN, Bamvita JM, et al. Predictors of healthcare service utilization for mental health reasons. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(10):10559–10586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eaton WW, Anthony JC, Tepper S, et al. Psychopathology and attrition in the epidemiologic catchment area surveys. Am J Epidemiol 1992;135(9):1051–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bucholz KK, Shayka JJ, Marion SL, et al. Is a history of alcohol problems or of psychiatric disorder associated with attrition at 11-year follow-up? Ann Epidemiol. 1996;6(3):228–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):184–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kessler RC, Andrews G, Mroczek D, et al. The World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short-Form (CIDI-SF). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1998;7(4):171–185. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Statistics Canada. Canadian Community Health Survey. Cycle 1.2. Mental health and well-being. 2002. Available from: www.statcan.gc.ca/concepts/healthsante/cycle1_2/content-contenu-eng.htm.

- 20. Nario-Redmond MR, Coulton CJ, Milligan SE. Measuring resident perceptions of neighborhood conditions: survey methodology. Cleveland (OH): Case Western Reserve University, Center on Urban Poverty and Social Change; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Weuve J, Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ, Glymour MM, et al. Accounting for bias due to selective attrition: the example of smoking and cognitive decline. Epidemiology. 2012;23(1):119–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wetherell JL, Reynolds CA, Gatz M, et al. Anxiety, cognitive performance, and cognitive decline in normal aging. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57(3):P246–P255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Paradise MB, Glozier NS, Naismith SL, et al. Subjective memory complaints, vascular risk factors and psychological distress in the middle-aged: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Anstey K, Christensen H. Education, activity, health, blood pressure and apolipoprotein E as predictors of cognitive change in old age: a review. Gerontology. 2000;46(3):163–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tucker-Drob EM, Johnson KE, Jones RN. The cognitive reserve hypothesis: a longitudinal examination of age-associated declines in reasoning and processing speed. Dev Psychol. 2009;45(2):431–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rickenbach EH, Condeelis KL, Haley WE. Daily stressors and emotional reactivity in individuals with mild cognitive impairment and cognitively healthy controls. Psychol Aging. 2015;30(2):420–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rickenbach EH, Almeida DM, Seeman TE, et al. Daily stress magnifies the association between cognitive decline and everyday memory problems: an integration of longitudinal and diary methods. Psychol Aging. 2014;29(4):852–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Albanese E, Matthews KA, Zhang J, et al. Hostile attitudes and effortful coping in young adulthood predict cognition 25 years later. Neurology. 2016;86(13):1227–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]