Abstract

Background:

Cluster B personality disorders (PDs) are prevalent mental health conditions in the general population (1%-6% depending on the subtype and study). Affected patients are known to be heavier users of both mental and medical health care systems than patients with other clinical conditions such as depression.

Methods:

Several rates were estimated using data from the integrated monitoring system for chronic diseases in the province of Quebec, Canada. It provides a profile of annual and period prevalence rates, mortality rates, and years of lost life as well as health care utilisation rates for Quebec residents. All Quebec residents are covered by a universal publicly managed care health plan. It is estimated that the monitoring system includes 99% of Quebec’s 8 million inhabitants.

Results:

Quebec residents aged 14 years and older were included in the study. The lifetime prevalence of cluster B PDs was 2.6%. The mean years of lost life expectancy were 13 for men and 9 for women compared to the provincial population. The 3 most important causes of death are suicide (20.4%), cardiovascular diseases (19.1%), and cancers (18.6%). In 2011 to 2012, 78% had consulted a general practitioner and 62% a psychiatrist, 44% were admitted to an emergency department, and 22% were hospitalised.

Conclusions:

Considering mortality, cluster B personality disorder is a severe condition, is highly prevalent in the population, and is associated with heavy health care services utilisation, especially in emergency settings.

Keywords: suicide, premature mortality, epidemiology, borderline personality disorder

Abstract

Contexte:

Les troubles de la personnalité (TP) du groupe B sont des conditions prévalentes dans la population générales (1 à 6% selon le sous-type et les études). Les patients qui en souffrent sont reconnus pour être de plus important utilisateurs des systèmes de santé mentale et médicale que les patients souffrant d’autres affections cliniques comme la dépression.

Méthodes:

Le Système Intégré de Surveillance des Maladies Chroniques du Québec permet d’estimer plusieurs données concernant les TP du groupe B dans la province de Québec. Il donne ainsi leur prévalence annuelle et cumulée, leur taux de mortalité, leur nombre moyen d’années de vie perdu et aussi leurs taux d’utilisation de service. Tous les résidents de la province sont couverts par un système de santé universel et public. On estime que le système de surveillance inclut 99% des 8 millions d’habitants du Québec.

Résultats:

Les résidents du Québec de 14 ans et plus ont été inclus dans l’étude. La prévalence cumulée des TP du groupe B est de 2,6%. Le nombre moyen d’années de vie perdues est de 13 pour les hommes et de 9 pour les femmes, comparativement à la population générale. Les 3 principales causes de décès sont le suicide (20,4%), les maladies cardiovasculaires (19,1%) et les cancers (18,6%). En 2011-2012, 78% ont consulté un omnipraticien, 62% un psychiatre, 44% ont été admis dans un service d’urgence, et 22% ont été hospitalisés.

Conclusions:

Compte tenu de la mortalité, les TP du groupe B sont graves. Ils sont hautement prévalent dans la population, et ils sont associés à une importante utilisation des services de santé, en particulier dans les services d’urgence.

The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5)1 categorised personality disorders (PDs) in 3 clusters (A, B, and C). Cluster B or dramatic cluster consists of 4 subtypes, which are antisocial, borderline, histrionic, and narcissistic PD. Patients with cluster B PDs receive special attention because of the severity of their symptoms (e.g., suicide). Moreover, most psychotherapeutic treatments (e.g., Dialectical Behavior Therapy [DBT] and Mentalization Based Therapy [MBT]) are dedicated to these patients. People with these features present with psychosocial functioning problems, suicidal behaviours, and psychiatric comorbidities. Psychotherapy seems the most effective treatment.2

PD prevalence in the general population was estimated between 13.4% and 14.8%.3 The prevalence ranges for each cluster B PD are as follows: antisocial, 0.7 to 3.6; borderline, 0.7 to 5.9; histrionic, 2.0; and narcissistic, 0.8 to 6.2. One of the limitations of these studies is that they do not discriminate between people diagnosed with a PD as the main problem from patients diagnosed with a PD as a comorbidity. Within these populations, we might have people who do not seek treatment or those for whom PD is not the main problem. For example, in the case of a person with severe substance abuse and histrionic PD, the patient and clinician might prefer treating the substance abuse first (or only). Thus, public health policy might misleadingly include people for whom PD is the main problem and others with comorbid PDs not seeking any type of service in the same group. In fact, these rates based on semi-structured interviews might overestimate PDs in terms of patients who require treatment.4 An evaluation based on clinical diagnoses does not allow for the generalisation of all patients with PDs but might better describe public health priorities. Another point concerns the lack of prevalence studies in Canada related to PD disorders.

A previous study indicated the importance of the gap found between the prevalence of patients with PDs included in administrative databases and the prevalence of those in the general population: 2 patients with cluster B PDs are identified using clinical databases for every 10 identified in general population surveys.5 (The clinical record includes the following values: sensitivity = 15%, specificity = 97%, positive predictive value = 33.3%, and negative predictive value = 91.3%.)

The loss of life is estimated between 13 and 25 years compared to the general population.6,7 This is a possible overestimation due to sample bias. The 2 cohorts were recruited in psychiatric settings (in one case, hospitalised patients) and could therefore have selected the most severe PD patients. As such, studies that recruit in both medical and psychiatric settings might provide a more generalizable estimation of the years of lost life. Another study pointed out that mortality is far more important for men with PD than for women.8

Finally, several studies have highlighted both the elevated level of health care utilisation9 and its global cost for society, which is estimated to be between 15,000 and 50,000 CAD per patient per year.10 However, most Canadian citizens could not reach appropriate psychotherapeutic programs, especially the longest ones dedicated to PDs. This could affect patients first, but also general practitioners, mental health practitioners (i.e., motivation to treat or competency), and society (i.e., cost, social impact).11

We aimed to assess cluster B PD diagnosis in relation to prevalence, causes of mortality, years of lost life expectancy, and health care utilisation. We compared the life expectancy and health care use with control groups (general population, mental disorders, anxiety/depressive disorders, and schizophrenia).

Method

Setting

We conducted a population-based observational study among Quebec residents aged 14 years and older, who were registered in the provincial health care insurance system (RAMQ: Régie d’Assurance Maladie du Quebec), between April 1, 2001, and March 31, 2012. We used the Quebec Integrated Chronic Disease Surveillance System (QICDSS),12 which links 5 health administrative databases (including the RAMQ). The QICDSS allows a longitudinal follow-up of individuals and contains information on diagnosis, cause of death, physician specialty, and the place where the service was rendered, among others.

Data Sources

Quebec, like other Canadian provinces, has a managed care system for public health and social services. More than 99% of the population of nearly 8 million inhabitants are included in the QICDSS.12 A quality study of the QICDSS13 showed that at least 95% of psychiatrists’ health care claims include a diagnosis, and nearly 90% of all claims include one.

Identification of Cases

To be considered as having a cluster B PD, an individual aged 14 years or older should have received during the year (April 1 to March 31) a cluster B PD diagnosis (medical services or hospital admissions file) according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) classification. For period prevalence, the diagnosis was retained regardless of when in the individual lifetime history the diagnosis was made.

A group composed of 4 psychiatrists and 1 psychologist working in Quebec with expertise in the treatment of PDs prepared the case definitions. (All of the experts worked in specialised programs across 3 areas.) The case definition was obtained via consensus after 2 multisite work sessions. The main objective for the selection was to obtain the most clinically relevant data. All selected ICD-9 codes are clinical entities included or close to the construct of a cluster B PD. Basically, this procedure transforms an ICD-9 diagnosis into a DSM category.

We included all ICD-9 diagnoses of 301.9 (PD unspecified) as part of cluster B, since the expert group considered that this code is commonly used to describe borderline personality disorder.

No formal study has been conducted to validate cluster B PD diagnoses. However, a study in Ontario14 that validated the case definition of mood and anxiety disorders in administrative data found a sensitivity of 68%, a specificity of 93%, a positive predictive value of 50%, and a negative predictive value of 97%. Thus, while administrative data are limited in their ability to correctly identify patients with mental health conditions, these data can be used to identify health care contacts for mental health conditions.

To compare use of services, we created control groups: the general population, all mental disorders, anxiety/depressive disorders, and schizophrenia. To be considered as having a mental disorder, an individual 1 year or older must have received a diagnosis of a mental disorder in his or her medical services file over the year (April 1 to March 31), including general mental disorders (ICD-9 codes: 290-319), anxiety/depressive disorders (296, 300, 311), or schizophrenia (295).

Measurement of Prevalence and Periods Covered

Annual prevalence was calculated using age-adjusted measures obtained with direct standardisation using the age structure of the population of Quebec in 2001.

Calculation of Mortality

Life expectancy at age 20 years of people with cluster B PD was calculated using abridged life tables from Chiang’s method15 by 5-year age groups. Calculations were based on mortality data observed over a 10-year period from April 2001 to March 2011.

An analysis examining causes of death obtained from vital statistics takes into account deaths in a year among people meeting the case definition of cluster B PD during that year. Excess mortality stratified by leading causes of death in persons with mental disorders was calculated using reports on age-adjusted mortality rates; they are presented according to whether the individual has a cluster B PD. The adjusted death rate ratio indicates the age-adjusted mortality rate for each category of cause of death for people with cluster B PDs divided by that of the people who do not have these disorders. A ratio of 1 denotes that the mortality rates are comparable between the 2 groups (with cluster B PDs vs. without cluster B PDs). A ratio of greater than 1 denotes that the mortality rate is higher for people with cluster B PDs. To be considered as having a personality disorder, a person had to meet the case definition during the year when the death was recorded. Finally, note that the cases of death were recorded from 2000 to 2009.

Definition of Services

Service utilisation profiles were constructed based on place where services from 2011 to 2012 were rendered (within hospitals, emergency, and ambulatory) and by specialty of the physician involved (general practitioner, psychiatrist, and other specialist). A hierarchical profile was created to consider the fact that a single individual may have consulted various professionals or used a variety of health services during the same period. The categories are ranked in order of intensity from hospitalisation, emergency, psychiatry outpatient, general practitioner (GP) outpatient, and other medical specialist outpatient. If an individual was seen in more than 1 sitting in the same year, the analyses reported the most intensive type of service used.

Results

Prevalence

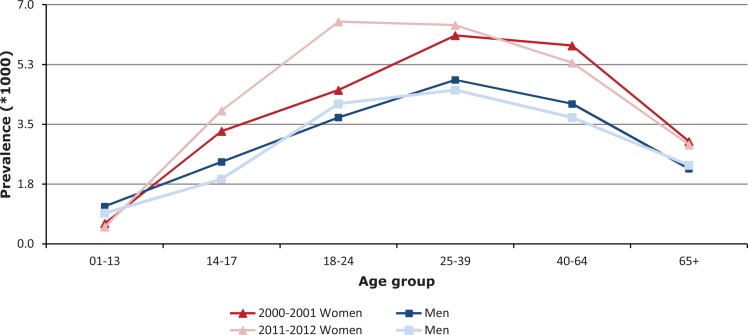

The period prevalence of diagnosed cluster B PD was 2.6% (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.59%-2.61%), which represents 207,369 individuals who at one point in the specified prevalence period received a diagnosis of cluster B PD. Evolution of annual prevalence according to age, sex, and time of diagnostic is represented in Figure 1. In 2011-2012, the annual cluster B PD prevalence was 3.6% (95% CI, 3.6%-3.7%), which represents 28,621 individuals.

Figure 1.

Cluster B personality disorder annual prevalence according to age and sex, Quebec, 2000-2001 and 2011-2012.

Mortality

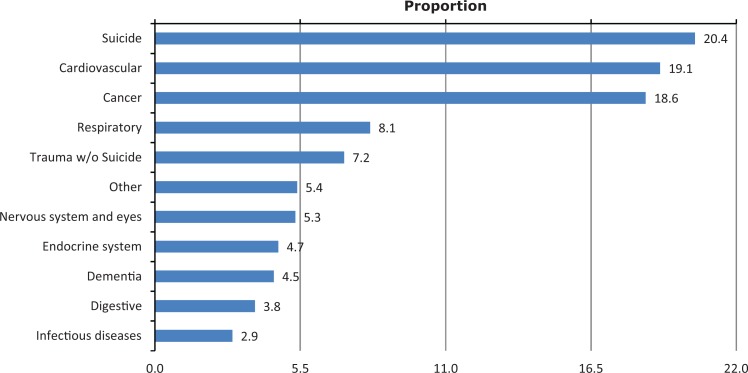

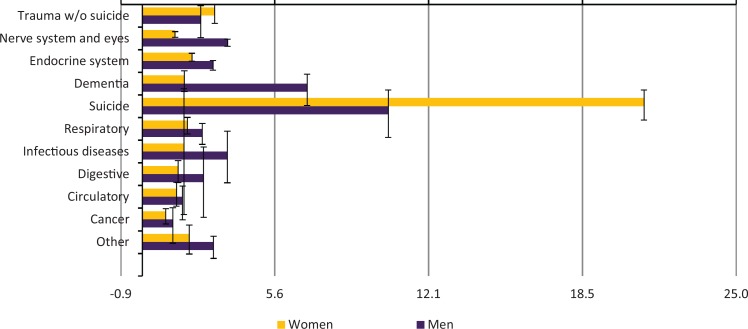

For men and women with cluster B PD, life expectancy at age 20 years was 46 and 55 years, respectively. For the same period, the mean life expectancy in the provincial population was 59 years for men and 64 years for women, and for all mental disorders, it was 51 and 59 years, respectively. The 3 most important causes of death were suicide (n = 600, 20.4%), cardiovascular diseases (n = 561, 19.1%), and cancers (n = 545, 18.6%) (Figure 2). The age-adjusted death ratio (ADR) was higher in the cluster B PD (Figure 3); there was no diagnostic category in which this ratio was less than 1. This means that for each category of death (natural or not, such as suicide), there was excess mortality of the population of patients with cluster B PD compared to the general population.

Figure 2.

Cause of death (%) of patients with cluster B personality disorder, Quebec, 2000-2009.

Figure 3.

Age-adjusted death ratio (ADR) for each cause of death among those with cluster B personality disorder according to their sex, with 95% confidence interval (black bar interval).

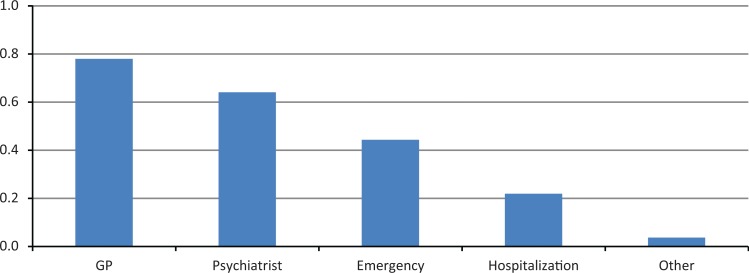

Health Care Utilisation

In 2011 to 2012, 78% of people with cluster B PD had consulted a GP and 62% a psychiatrist, 44% were admitted to an emergency department, and 22% were hospitalised (Figure 4). Comparative hierarchical services utilisation (Table 1) indicates that the pattern of use of services differed between individuals with common mental disorders such as anxiety and depression, who mostly used primary care physicians, and those with severe mental disorders such as schizophrenia and cluster B PD, who mostly sought services with specialists.

Figure 4.

Health care use profile among cluster B personality disorder, Quebec, 2011-2012.

Table 1.

Hierarchical Profile of Health Care Use among Cluster B Personality Disorders (PDs), Anxiety/Depression Disorders, and Schizophrenia, Quebec, 2011-2012.

| Cluster B PD | Anxiety/Depressive Disorders | Schizophrenia | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion | 99% CI | Proportion | 99% CI | Proportion | 99% CI | |

| Hospital inpatient | 21.9 | 21.0-22.7 | 4.4 | 4.3-4.5 | 28.4 | 26.6-30.4 |

| Emergency | 25.1 | 24.2-26.1 | 10.8 | 10.6-10.9 | 13.3 | 12.0-14.7 |

| Psychiatrist outpatient | 23.1 | 22.3-23.9 | 14.0 | 13.8-14.2 | 37.2 | 35.7-38.9 |

| General practitioner outpatient | 26.4 | 25.5-27.4 | 65.3 | 65.0-65.6 | 18.4 | 16.9-20.0 |

| Other specialty outpatient | 3.5 | 3.1-4.0 | 5.5 | 5.4-5.7 | 2.7 | 2.1-3.5 |

CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

This study has 3 main findings. First, cluster B PD is prevalent in clinical populations. Second, this diagnosis is associated with a loss of 9 to 13 years of life expectancy at age 20 years, explained by both suicide rate and medical comorbidities. Third, individuals with cluster B PD are prominent users of both general and specialised health care settings.

As demonstrated in previous studies,5 the portrait drawn from the results of administrative databases may be different from results from epidemiological surveys, suggesting this condition goes undiagnosed and untreated.3 However, some recent studies found more comparable prevalence (3.2% among women),16 suggesting previous methods have overestimated their rate. Other studies argue that a bipolar disorder diagnosis is preferred to PD.17

Our study captures patients who seek care in the public health system for that specific problem. In other words, those with highly functional PD who prefer consulting private psychologists or those for whom a comorbidity (i.e., substance abuse) is the main problem may not have been included. However, the picture drawn by the present results offers a more accurate view for public health services providers.

Previous publications have shown an excess of mortality in the PD population.6–8 Our results confirm these data, but with a lower loss of years of life. It may be due to sample difference: the entire population versus psychiatric inpatients or outpatients.

Suicide is a leading cause of death among this population, which is not surprising considering previous data18 and nosographic considerations. Borderline PD (BPD) and narcissistic PD may be the higher contributors.19 Suicide among BPD patients may be more impulsive than among narcissistic patients, which has led some authors to consider different psychotherapeutic strategies.20 Moreover, if impulsivity decreases with age, elderly patients with narcissistic disorder may remain vulnerable to suicide.21

If we project the risk of suicide in patients with PD using the current study and suicide statistics,22 we would estimate around 250 deaths by suicide among PD patients among 1100 suicides in Quebec each year.

The ADR for suicide among women (21.1) is approximatively twice that among men (10.3). This way of expressing the excess of mortality should not be interpreted as if women (ratio: 137.9 deaths cause by suicide per 100,000 persons) committed more suicides than men (255.9). Women with a cluster B PD have a higher risk of death by suicide than other women. The risk for cluster B PD men to die by suicide remains higher (odds ratio [OR] approximately 1.8) than that for women. However, this gender effect seems to be lower than in the general population (OR approximately 3.8 in our sample).

Cluster B PD presents an excess of mortality in all other causes of death than suicide, which is consistent with the growing literature on the subject.6–8 Lifestyle and sociodemographic characteristics, as well as comorbidities, could explain this difference. However, at least one other study challenges these hypotheses.23

Further research may consider the causes of the excess of mortality. Moreover, it may be beneficial to include mortality outcomes in randomised controlled trials assessing new treatments. Also, these data show the importance of suicide prevention and medical treatment for these patients (at least cancer screening and cardiovascular prevention). Lastly, cluster B PD appears as consequential in terms of premature mortality as other psychiatric disorders and some other physical diseases (i.e., same loss of years of life vs. diabetes). So this disorder challenges a conventional view of psychiatry that focuses on treatment of psychotic and bipolar disorders and psychotherapeutic treatments. We have an urgent need to consider fund allocation in this field.

The main limitation concerns the diagnostic methods (not standardised with a structured interview). In addition, we lack information concerning the validity of the algorithm used to identify cases in the database. Moreover, we have only 1 diagnosis per episode (e.g., consultation and hospitalisation), which prevents us from analysing the effect of comorbidity on the outcomes. In addition, our method prevents us from analysing remission rates. Also, data from psychologists in private practice or patients coming from other provinces are not registered in the database system. These limitations could decrease both prevalence and measures of burden on health care estimations. Finally, we do not have information regarding lifestyle habits or other factors that might explain the mortality rate. The main strengths of this study consist of the power of a study conducted on the whole population of Quebec.

Conclusion

Considering their severity and their prevalence, cluster B PD should be considered an important priority. Unfortunately, for historical reasons and stigmatisation, access to evidence-based treatment is not universal. Consequences could be seen in terms of loss of years of life, cost to society, and suffering for patients and their relatives.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Borderline personality disorder: treatment and management. 2009. Available from: http://publications.nice.org.uk/borderline-personality-disorder-cg78/guidance. Accessed 2017. [PubMed]

- 3. Torgersen S, Kringlen E, Cramer V. The prevalence of personality disorders in a community sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(6):590–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Paris J. Estimating the prevalence of personality disorders in the community. J Pers Disord. 2010;24(4):405–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Comtois KA, Carmel A. Borderline personality disorder and high utilization of inpatient psychiatric hospitalization: concordance between research and clinical diagnosis. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2016;43(2):272–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fok ML, Hayes RD, Chang CK, et al. Life expectancy at birth and all-cause mortality among people with personality disorder. J Psychosom Res. 2012;73(2):104–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ajetunmobi O, Taylor M, Stockton D, et al. Early death in those previously hospitalised for mental healthcare in Scotland: a nationwide cohort study, 1986-2010. BMJ Open. 2013;3(7):e002768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hoye A, Jacobsen BK, Hansen V. Sex differences in mortality of admitted patients with personality disorders in North Norway—a prospective register study. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Comtois KA, Russo J, Snowden M, et al. Factors associated with high use of public mental health services by persons with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(8):1149–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van Asselt AD, Dirksen CD, Arntz A, et al. The cost of borderline personality disorder: societal cost of illness in BPD-patients. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22(6):354–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Peachey D, Hicks V, Adams O. An imperative for change access to psychological services for Canada: a report to the Canadian Psychological Association. 2013. Available from: http://www.cpa.ca/docs/File/Position/An_Imperative_for_Change.pdf. Accessed 2017.

- 12. Blais C, Jean S, Sirois C, et al. Quebec integrated chronic disease surveillance system (QICDSS), an innovative approach. Chronic Dis Inj Can. 2014;34(4):226–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gagnon R. Cadre de qualité des données du Système intégré de surveillance des maladies chroniques du Québec. Rapport méthodologique. Québec City (QC): Institut national de santé publique, Bureau d’information et d’études en santé des populations; in press. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tu K, Wang M, Ivers N, et al. Case definition validation study for mental illness surveillance in Canada. Toronto (ON: ): Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chiang C. Life table and its application. Malabar (FL): Robert E; Krieger Publishing; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Quirck SE, Berk M, Pasco JA, et al. The prevalence, age distribution and comorbidity of personality disorders in Australian women. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2017;51(2):141–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zimmerman M, Morgan TA. Problematic boundaries in the diagnosis of bipolar disorder: the interface with borderline personality disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15(12):422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Arsenault-Lapierre G, Kim C, Turecki G. Psychiatric diagnoses in 3275 suicides: a meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4:4–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ansell EB, Wright AG, Markowitz JC, et al. Personality disorder risk factors for suicide attempts over 10 years of follow-up. Personal Disord. 2015;6(2):161–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Blasco-Fontecilla H, Baca-Garcia E, Denvic K, et al. Specific features of suicidal behavior in patients with narcissistic personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(11):1583–1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Heisel MJ, Links PS, Conn D, et al. Narcissistic personality and vulnerability to late-life suicidality. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15(9):734–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lesage A, St-Laurent D, Gagne M, et al. Suicide prevention from a public health perspective [in French]. Sante Ment Que. 2012;37(2):239–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Quirck SE, Stuart AL, Bennan-Olsen SL, et al. Physical health comorbidities in women with personality disorder: data from Geelong Osteoporosis Study. Eur Psychiatry. 2016;34:29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]