Abstract

HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) occur in approximately 50% of HIV-infected individuals, yet available diagnostic criteria yield varying prevalence rates. This study examined the frequency, reliability, and sensitivity to everyday functioning problems of three HAND diagnostic criteria (DSM-5, Frascati, Gisslén). Participants included 361 adults with HIV disease and 199 seronegative adults. Neurocognitive status as defined by each of the three diagnostic systems was determined via a comprehensive neuropsychological battery. Everyday functioning was evaluated through self-report and clinician ratings. Results of logistic regressions revealed an association of HIV serostatus with Frascati-defined neurocognitive impairment (p=.027, OR=1.7[1.1, 2.7]), but not DSM-5 or Gisslén-defined criteria (ps>.05). Frascati and DSM-5 criteria demonstrated agreement on 71% of observations, Frascati and Gisslén showed agreement on 80%, and DSM-5 and Gisslén criteria showed agreement on 46%, though reliability across the three criteria was poor. Only Frascati-defined neurocognitive impairment significantly predicted everyday functioning problems (p=.002, OR=2.3[1.4,3.8]). However, when both neurocognitive and complaint criteria were considered, the DSM-5 guidelines demonstrated significant relationships to everyday functioning, serostatus and also increased reliability overtime compared to neurocognitive criteria alone (all ps < .05). A subset (n = 118) of the HIV+ group was assessed again after 14.0 (2.2) months. DSM-5 criteria evidenced significantly higher rates of incident neurocognitive disorder compared to both Frascati (p = .003) and Gisslén (p = .021) guidelines, while there were fewer remitting neurocognitive disorder diagnoses when Gisslén criteria were applied to the study sample compared to Frascati (p = .04). Future studies should aim to identify gold standard biological markers (e.g., neuropathology) and clinical outcomes associated with specific diagnostic criteria.

Keywords: HIV, Neuropsychology, Neurocognitive Disorders, Diagnosis

The era of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) has transformed human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) into a chronic yet manageable disease. Despite the reduced rates of mortality and morbidity in this era, individuals living with HIV remain at increased risk for developing a number of disease-related complications, including HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND). Indeed, initiation of cART is not strongly neuroprotective or restorative, and is associated with only very mild improvement in a few select neurocognitive domains (Al-Khindi et al., 2011). Thus, the incidence and prevalence of HAND continue to persist at high levels. Although the rates of moderate to severe HIV associated dementia have fallen from approximately 7% to 1–2% over the last twenty years (Heaton et al., 2011), the prevalence of milder forms of HAND (e.g., asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment) have increased from approximately 25 to 33%, especially among persons with less advanced HIV disease (Heaton et al., 2010). This trend is clinically relevant, as even milder forms of HAND affect everyday functioning and health outcomes, including medication non-adherence (Hinkin et al., 2002), dependence in household activities (e.g., Heaton et al., 2004), and mortality (Sevigny et al., 2007). Thus, it is important to have reliable and valid schemes to diagnose HAND that can be applied in both clinical and research settings.

In general, a diagnosis of HAND is marked by clinically significant declines in multiple domains of neurocognitive functioning that are not exclusively attributed to factors other than HIV infection. Several diagnostic schemes have been proposed over the years, though controversy exists over their relative utility. Early diagnostic guidelines emphasized the motor, psychosocial, and behavioral symptoms that accompanied neurocognitive impairment (AAN; American Academy of Neurology AIDs Task Force, 1991), rather than the thresholds by which the presence and severity of the impairment was defined. In 2007, these requirements evolved and were refined into what is now known as the Frascati criteria (Antinori et al, 2007). Still, controversy about specificity of these revised guidelines led to yet another revision emphasizing more conservative cutpoints for impairment, known as the Gisslén criteria (Gisslén et al., 2011). Most recently, diagnostic criteria set forth by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.; DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) offered fewer levels of HAND (i.e., 2 versus 3) but more stringent requirements regarding impairment of daily functioning. Inconsistencies among diagnostic schemes lead to substantial discrepancies in prevalence rates of HAND (Su et al., 2015) and underscore the need to understand the interrelationships between these various diagnostic guidelines.

The Frascati criteria (Antinori et al., 2007) are the most widely used nosology of HAND and are considered the gold standard in HIV research. The Frascati diagnostic scheme identifies three severity levels of HAND: asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment (ANI), mild neurocognitive disorder (MND) and HIV associated dementia (HAD). The three severity levels of HAND differ by (a) the thresholds required for the assignment of neurocognitive impairment and (b) the extent to which such impairment interferes with everyday functioning. ANI is defined as mild-to-moderate neurocognitive impairment demonstrated by performance falling 1 standard deviation (SD) below the mean of demographically adjusted normative scores in 2 of at least 5 measured domains. “Asymptomatic” means that the demonstrated cognitive impairment in ANI is not accompanied by clinically significant difficulties in everyday functioning. MND is also characterized by the mild-to-moderate impairment in cognitive functioning, however, a classification of MND requires evidence that the impairment imposes mild interference with daily functioning (e.g. needing assistance with 2 or more activities of daily living, reduced efficiency at work). The most severe of the three subtypes, HAD, is characterized by a marked impairment in cognitive functioning as documented by 2SD below the mean of demographically adjusted normative scores in 2 domains accompanied by pronounced difficulty in ADLs (e.g. incapacity to work, >2 SD below the mean of a performance based task). Application of Frascati criteria produces prevalence rates for ANI, MND, and HAD of 33–45%, 12%–28%, and 2–4%, respectively (Heaton et al., 2010; Simioni et al., 2010) and incidence rates of HAND are estimated to be near 15–20% (Robertson et al., 2007). Frascati-derived HAND diagnoses have been associated with several clinically meaningful outcomes such as poorer self-reported health indices (Simioni et al., 2010), objective measures of functional impairment (Ghandi et al., 2011), grey and white matter brain abnormalities (e.g., volumetric differences, Haziot, et al., 2015), and plasma biomarkers (e.g., nadir CD4 count; Chan & Brew, 2014).

Whereas the Frascati criteria emphasize sensitivity to deficits associated with HAND, the criteria outlined by Gisslén, et al. (2011) emphasize specificity. Gisslén et al. (2011) set a threshold of 1.5 SD, rather than 1 SD below the normative mean to determine impairment in ANI and MND. Central to the argument posed by Gisslén et al. (2011) is that the more liberal 1 SD diagnostic thresholds yield an overestimation of cognitive impairment. While 16% of any given population is expected to score more than one SD below the mean (i.e., abnormal) on a single neuropsychological test, Gisslén and colleagues report that probability of an abnormal score is 18–21% when using one test (or average of tests) per domain in at least two of five domains tested in an HIV+ sample. Furthermore, the probability of an abnormal score increases as number of tests per domain and number of assessed domains increase. Gisslén and colleagues (2011) also raised ethical concerns regarding the diagnosis of neurocognitive impairment in the absence of symptoms or complaint; given the uncertain relevance of ANI, the diagnosis may cause unnecessary anxiety and impact employment without cause (cf., Grant et al., 2014). Using the Gisslén criteria, prevalence of HAND is generally estimated to be between 5–10%, with rates of ANI and MND as low as 4% and 1% respectively (Su et al., 2015). Little is known about incidence rates, as there have been no known longitudinal studies examining the persistence of Gisslén-determined HAND. Moreover, as few studies have utilized the Gisslén approach, support for its criterion or construct validity is presently limited.

The DSM-5 also provides guidelines for diagnosing HAND by stratifying neurocognitive disorders into two categories: Mild and Major. Mild HAND is evidenced by modest cognitive decline from a previous level of performance in one or more cognitive domains and no interference with independence in everyday living. In contrast, Major HAND is evidenced by significant cognitive decline from a previous level of performance in one or more cognitive domains, and at least some interference with everyday activities (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). While the DSM-5 does not identify specific thresholds of impairment, the authors note that performance is typically below 1 SD in Mild HAND and below 2 SD in Major HAND. Notably, the DSM -5 requires both objective (e.g., decline in standardized neuropsychological testing) and subjective (e.g., complaints) evidence of impairment, whereas evidence of subjective impairment is not always necessary for the aforementioned criteria. To our knowledge, there have been no studies to date that have evaluated the application of DSM-5 criteria for HAND.

Reaching a reliable and valid diagnosis of HAND can be complicated by this lack of consistency and noteworthy differences across classification schemes. For example, the DSM-5 only offers two levels of HAND categorization, thereby being subject to the similar criticisms of earlier nosologies for HAND that predated Frascati (e.g. Antinori et al., 2007). The DSM-5 also permits a diagnosis of HAND when cognitive decline is observed in at least one domain, as opposed to at least two, which echoes concern of false positive rates and overestimation of prevalence with Frascati criteria (e.g., Gisslén et al., 2011; Meyer et al., 2013). Of note, a recent study that applied both criteria to the same sample reported that prevalence of HAND was 48% in seropositives and 36% in seronegatives when the Frascati method was used, but fell to 5% and 1%, respectively, when the Gisslén method used (Su et al., 2015). Thus, specificity was improved, but sensitivity to HIV was reduced. However, as there is currently no definitive biomarker of HAND and data of confirmed HAND diagnosis were not available (i.e., gold standard) for comparison, it is possible that the frequencies of false positives when applying Frascati criteria may have been over estimated, or that the more conservative approach may have underestimated HAND prevalence. Additionally, the controversy surrounding requirements for HAND subtypes involving functional impairment (e.g., MND and HAD) and subtypes free of functional deficits (e.g., ANI) further muddles the reliability and validity of HAND diagnoses.

To the authors’ knowledge, there have been no studies to date that have directly compared the rates of HAND in a large, well characterized sample across these three diagnostic methods: Frascati, Gisslén, and DSM-5. The current study sought to elucidate the similarities and differences among these methodologies and to extend extant literature in the three following ways: 1) to directly compare DSM-5 guidelines to the Frascati and Gisslén criteria; 2) to examine the criteria over a one-year time period to assess agreement and stability of diagnoses; and 3) to examine neurocognitive impairment criteria as independent predictors of everyday functioning across the three diagnostic schemes. Consistent with previous literature (e.g., Su et al., 2015), the highest rates of HAND were hypothesized to result from application of the Frascati criteria, followed by the DSM-5 (APA, 2013), while the diagnostic requirements proposed by Gisslén et al., (2011) were expected to result in the lowest frequency of HAND.

Method

Participants

The current study included both cross-sectional and longitudinal elements. Cross-sectional data were used to evaluate the overall sensitivity to HIV status and relationship to functional outcomes of the three diagnostic schemes, while longitudinal data were used to assess stability in HAND diagnoses.

Cross-sectional group

The total study sample included 560 individuals aged 18–83 years (M =44.62, SD = 13.02), recruited from the University of California San Diego (UCSD) Neurobehavioral Research Program. Baseline exclusion criteria for this study included an estimated verbal IQ score less than 70 on the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR; Psychological Corporation, 2001), or prior diagnosis of any of the following: (1) severe psychiatric disorder (e.g., schizophrenia); (2) neuromedical condition involving an active central nervous system opportunistic infection; (3) seizure disorder; (4) head injury with loss of consciousness for more than 30 min; (5) stroke with neurological sequelae; or (6) presence of a non-HAD neurodegenerative disorder. Individuals were also excluded if they had current substance dependence or tested positive on a breathalyzer or urine toxicology screen for illicit drugs (except marijuana) on the day of testing. Participant demographic and disease characteristic information for the entire cohort is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic, psychiatric, medical, and HIV disease characteristics of the study groups.

| HIV− (n = 199) | HIV+ (n = 361) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 42.8 (1.0) | 45.5 (0.6) | .058 |

| Education (years) | 14.3 (0.2) | 13.5 (0.1) | < .001 |

| Employment Status (% employed) | 77.9% | 77.9% | .187 |

| Gender (% men) | 65.3% | 85.9% | < .001 |

| Ethnicity | .743 | ||

| African American | 22.1% | 23.6% | -- |

| Asian | 2.0% | 1.4% | -- |

| Caucasian | 56.3% | 58.2% | -- |

| Hispanic | 18.1% | 16.3% | -- |

| Native American | 1.5% | 0.6% | -- |

| Verbal IQ (WTAR) | 103.8 (0.8) | 102.3 (0.6) | .170 |

| POMS Total Mood Disturbance | 42.8 (2.0) | 58.4 (2.0) | < .001 |

| Major Depression† | 33.3% | 57.7% | < .001 |

| Generalized Anxiety† | 4.6% | 14.0% | < .001 |

| Substance Dependence‡ | 38.7% | 54.6% | <.001 |

| Hepatitis C virus | 8.7% | 18.2% | 0.003 |

| HIV | |||

| Duration of Infection (months) | -- | 158.8 (5.2) | -- |

| AIDS | -- | 56.4% | -- |

| Current CD4 count | -- | 565.5 (15.3) | -- |

| Nadir CD4 count | -- | 211.9 (9.7) | -- |

| Prescribed ART | -- | 85.3% | -- |

| Plasma RNA detectable in those prescribed cART | -- | 25.9% | -- |

| -- | 15.9% | -- | |

Note. Data are presented as means (standard error) or percentages. POMS = Profile of Mood States; AIDS = Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome; CD4 = Cluster of Differentiation 4; ART = antiretroviral therapy.

Includes current and lifetime diagnoses.

Any lifetime diagnosis of dependence on alcohol or illicit substance.

Longitudinal group

A subset of 146 participants from the cross-sectional analyses completed a one-year follow-up evaluation as part of normal study procedures. The mean (standard error) number of months between baseline and follow-up testing for all 146 retained participants included in analyses was 14.27 (SD = 2.73) months. Note that, this was an expected study procedure for only 366 of the 560 participants enrolled at different phases of the study. Thus, the retention rate for the total longitudinal time point was 40%. However, as the longitudinal component of the current study was concerned only with change in HAND neurocognitive diagnoses (rather than ability to differentiate from HIV- and HIV+ groups), only data from HIV+ participants were used in the longitudinal analyses. Thus, the longitudinal group included data from 118 HIV+ (32% of original 366) individuals aged 23–72 (M= 49.78, SD=12.61) with an average duration between testing of 13.98 (SD=2.16) months.

Materials and procedure

All participants provided written, informed consent prior to completing a comprehensive medical, psychiatric, and neuropsychological research evaluation for which they received nominal financial compensation. The human research ethics office at UCSD approved the study procedures.

Medical evaluation

Participants underwent a brief medical evaluation led by a research nurse, which included a review of systems, medications, history, urine toxicology, and a blood draw.

Psychiatric evaluation

Current mood symptoms were assessed using the Profile of Mood States (POMS; McNair et al., 1981), a 65-item self-report measure of affective distress in the week prior to evaluation. Current (i.e., within the last 30 days) and lifetime major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and substance use disorder were determined using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI version 2.128; World Health Organization, 1998).

Application of HAND Diagnostic Criteria

Across all diagnostic criteria, a diagnosis of HAND included consideration of neurocognitive, neuromedical, and everyday functioning data.

Neurocognitive assessment

All participants completed a comprehensive neuropsychological battery designed to measure the cognitive domains recommended in the Gisslén criteria (Gisslén et al., 2011), the Frascati criteria (Antinori et al., 2007), and the DSM-5 manual (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Measured domains and associated tests included: (1) Attention – assessed via the Digit Span subtest from Wechsler Memory Scale, 3rd edition (WMS-III; Wechsler, 1997) and Trial 1 from the California Verbal Learning Test, 2nd edition (CVLT-II; Delis et al., 2000) (2) Executive Function – assessed via the Total Moves score of the Tower of London Test and the Total Time score from the Trail Making Test, Part B (Army Individual Test Battery, 1944; Heaton et al., 2004); (3) Learning and Memory– Learning was assessed with Logical Memory I subtest from the WMS-III (Psychological Corporation, 1997) and Total Trials 1–5 of the CVLT-II (Delis et al., 2000), while Delayed Memory was assessed with the Logical Memory II subtest from the WMS-III and the Long Delay Free Recall trial of the CVLT-II (Delis et al., 2000); (4) Language – a domain used only in the classification of DSM-5 diagnoses, was assessed with the Boston Naming Test (BNT; Kaplan et al., 1983) and total words generated on a verbal (action) fluency test (see Woods et al., 2006; Piatt et al., 1999 for further details)(Note that the Language domain was not included in the longitudinal analyses this data was not available at both time-points); (5) Speed of Processing – assessed with the Total Time score from the Trail Making Test, Part A (Heaton et al., 2004) and the Total Execution Time from the Tower of London Test, Drexel Version (Culbertson & Zillmer, 2001); and (6) Motor – assessed with the dominant and non-dominant hand completion times from the Grooved Pegboard Test (Heaton et al., 2004; (Kløve, 1963). All measures were administered by trained research assistants and scored in accordance with published manuals. Raw scores were converted to demographically adjusted normative T-scores.

DSM-5 neurocognitive criteria

Neurocognitive criteria for HAND diagnosis using the DSM-5 were based on performance in the following five cognitive domains: Attention, Executive Function, Learning and Memory, Language (with the exception of the longitudinal data), and Perceptual-Motor. For DSM-5 criteria only, the Attention domain included tests associated with Speed of Processing domain in the Frascati and Gisslén schemes (see Neurocognitive Assessment above; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Due to the retrospective nature of this analysis, data from the Social Cognition domain were not available, and thus were not included in analyses. For DSM-5, participants met the minimum criteria for neurocognitive impairment (i.e., Mild HAND) if a normative T-score of any individual measure fell at or more than 1.5 SD(s) below the mean, or any two tests within a domain fell at or more than 1 SD(s) below the mean. Participants met the neurocognitive impairment criteria for Major HAND if a normative T-score of any individual measure among the included cognitive domains fell more than 2.5 SD(s) below the mean, or any two tests within a domain fell more than 2 SD(s) below the mean.

Frascati neurocognitive criteria

Neurocognitive criteria for HAND diagnosis using the Frascati criteria were based on performance in the following six cognitive domains: Attention, Executive Function, Learning, Memory, Speed of Processing, and Motor Skills. Unlike DSM-5 criteria, Attention and Speed of Processing were treated as separate cognitive domains. The Language domain was not included in HAND determinations. T-scores for measures within each domain were averaged to create composite domain scores using clinical ratings procedures (see Woods et al., 2004). For Frascati criteria, participants met the minimum requirements for neuropsychological impairment (i.e., neurocognitive impairment criteria for ANI and MND) if domain clinical ratings fell more than 1 SD below the mean for 2 or more of the evaluated domains. Participants met the requirements for severe neurocognitive impairment (i.e., neurocognitive impairment criteria for HAD) if composite scores fell more than 2 SDs below the mean for ≥2 of the evaluated domains.

Gisslén neurocognitive criteria

Dovetailing with the Frascati criteria, cognitive criteria for neuropsychological impairment as described by Gisslén were based on performance in the same six cognitive domains: Attention, Executive Function, Learning, Memory, Speed of Processing, and Motor skills. The Language domain was not included in HAND determinations. Composite domain scores were created by taking the average of T-scores for measures within each domain. The minimum criteria for neuropsychological impairment (i.e., neurocognitive criteria for ANI and MND) required composite domain scores that fell more than 1.5 SDs below the mean on 2 or more of the evaluated cognitive domains. Participants met the requirements for severe neurocognitive impairment (i.e., neurocognitive impairment criteria for HAD) if composite scores fell more than 2 SDs below the mean for 2 or more of the evaluated domains.

Everyday functioning assessment

For all diagnostic criteria, the presence of daily functioning impairment was assessed with the following indicators: (1) employment status (i.e., unemployed, exempting elective retirement status); (2) self-reported impairment in 2 or more instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) on a modified form (Heaton et al., 2004) of the Lawton and Brody ADL Scale (i.e., financial and medication management, grocery shopping, cooking, using transportation, and social activity planning; Lawton & Brody, 1969); (3) self-reported impairment in 2 or more basic activities of daily living (BADLs) on the modified ADL Scale (i.e., cleaning/housekeeping, home repair, laundry, bathing, and dressing; Heaton et al., 2004); (4) elevated POMS confusion and bewilderment scores more than 1 SD above the normative mean (McNair et al., 1981); and (5) a score of less than 90 on the clinician-rated Karnofsky Scale of Performance Status (Karnofsky & Burchenal, 1949).

Frascati and Gisslén functional impairment criteria

The minimum requirements (i.e., functional impairment criteria for MND) for functional impairment when participants demonstrated at least 2 of the following 3 criteria: (1) self-reported impairment in 2 or more IADLs on the modified ADL scale; (2) POMS scores were elevated more than 1 SD above the mean; or (3) Karnofsky score was less than 90. Participants met the requirements for severe functional impairment (i.e., functional impairment criteria for HAD) if at least 2 of the following 3 criteria were demonstrated: (1) self-reported impairment in 2 or more IADLs and 2 or more BADLS on the modified ADL scale; (2) employment status is unemployed

DSM-5 functional impairment criteria

Per requirements described in the DSM-5 diagnostic manual, severity of functional impairment was used to assign specifiers of Major HAND. By definition Mild HAND in the DSM-5 requires the absence of function problems. Participants were classified as having mild functional impairment if they demonstrated 1 or more problem(s) with IADLs without reported problems with BADLs, and in the presence of elevated scores on the POMS confusion and bewilderment subscale. Moderate functional impairment was defined as reported difficulties with at least one, but less than four BADLs in the presence of elevated POMS confusion and bewilderment scores. Finally, severe functional impairment was defined as 4 or more reported problems with BADLs in the presence of elevated POMS confusion and bewilderment scores.

Diagnosis assignment

Table 2 shows the cognitive and functional requirements for diagnoses of HAND characterized by each diagnostic criteria.

Table 2.

Summary of Gisslén, Frascati, and DSM-5 criteria for HIV- associated neurocognitive disorder

| DSM-5 | Frascati | Gisslén | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain Threshold for Mild Impairment | Score greater than 1, but less than 2 SD below the mean | Score ≥ 1 SD below on 2 tests, or ≥ 1.5 below on 1 test | Doman T-score > 1.5 SD below the mean |

| Domain Threshold for Major Impairment | Score greater than 2 SD below the mean | Score ≥ 2 SD below on 2 tests, or ≥ 2.5 below on 1 test | Domain T-score > 2 SD below mean |

| Minimum Number of Impaired Domains | ≥1 | ≥2 | ≥2 |

| Cognitive Domains Considered | |||

| Attention | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Executive Function | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Learning and Memory | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Language | ✔ | ||

| Speed of Processing | ✔* | ✔ | ✔ |

| Motor | ✔** | ✔ | ✔ |

| Perceptual-Motor | ✔ | ||

| Functional Domains Used in the Current Study | |||

| ADLs (IADLs & BADLs) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Employment status | ✔ | ✔ | |

| POMS (Confusion and Bewilderment) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Karnofsky | ✔ | ✔ | |

Note.

For DSM-5 criteria, Speed of Processing is subsumed within the Attention domain.

For DSM-5 criteria, Motor is subsumed within the Perceptual-Motor domain.

Frascati and Gisslén HAND diagnoses

Both the Frascati and Gisslén criteria identify three primary subtypes of HAND. HIV-associated Asymptomatic Neurocognitive Impairment (ANI) is characterized by mild, yet demonstrable neurocognitive impairment in at least two domains that does not contribute to functional decline (i.e., individual meets criteria for mild neurocognitive impairment with no evidence of functional difficulty). The remaining two subtypes, HIV-associated Mild Neurocognitive Disorder (MND) and HIV-associated Dementia (HAD) both require the presence of observable functional declines in multiple domains that can be attributed to the observed neurocognitive impairment (Antinori et al. 2007). Specifically, a diagnosis of MND would require that an individual meet criteria for mild neurocognitive impairment and also demonstrate minimum functional impairment. A diagnosis of HAD requires that an individual meet criteria for severe neurocognitive impairment in addition to criteria for severe functional impairment (see above for descriptions of functional and cognitive impairment).

DSM-5 Neurocognitive Criteria with ADL Specifier

Four possible diagnoses were assigned under the DSM-5 guidelines. First, Mild HAND was assigned to participants who met requirements for mild neurocognitive impairment in the absence of functional problems. Major HAND, with specifier of mild was assigned to participants if they met DSM-5 cognitive impairment requirements for Mild or Major neurocognitive disorder in the presence of mild functional impairment. Participants met requirements for Major HAND specified moderate if DSM-5 cognitive impairment requirements for Major neurocognitive disorder were met in the presence of moderate functional impairment. Finally, Major HAND specified severe was assigned if DSM-5 cognitive impairment requirements for Major Neurocognitive Disorder were met in the presence of severe functional impairment.

Longitudinal patterns of HAND diagnoses

Characterizations of incident neurocognitive disorder at one-year follow-up in the longitudinal cohort (n=118) were determined independently for each of the three diagnostic criteria in the same manner described above. Individuals were assigned an incident HAND diagnosis if they were characterized as neurocognitively ‘normal’ at baseline by a specific scheme and subsequently assigned a HAND diagnosis at the follow-up assessment by that same scheme; conversely, they were classified with a remitting HAND diagnosis if they evidenced that pattern in reverse. Individuals received a classification of stable HAND diagnosis if their diagnosis (i.e., either HAND or neurocognitively normal) was consistent at both baseline and follow-up assessment within each of the three diagnostic criteria respectively. Finally, Change (i.e., incident and remitting) and stability (i.e., no HAND diagnosis and consistent HAND diagnosis) in HAND diagnoses were assessed independently following this procedure within participants for each of the three diagnostic criteria.

Results

Cross-sectional Group Characteristics and Model Covariates

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the HIV- and HIV+ study groups are shown in Table 1. As none of the continuous variables listed in Table 1 were normally distributed (all Shapiro-Wilk W Tests ps < .05), non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sums tests were used for analyses. Regarding their demographic characteristics, the HIV+ group was slightly older (χ2[1] = 3.6, p = .058), reported fewer years of education (χ2[1] = 11.8, p < .001), and had a higher proportion of men (Fisher’s exact test p < .001). The HIV+ group also had higher POMS total mood disturbance scores (χ2[1] = 24.6, p < .001), and a greater lifetime prevalence of several common comorbidities, including Major Depressive Disorder (χ2[1] = 31.0, p < .001), Generalized Anxiety Disorder (χ2[1] = 13.5, p < .001), substance dependence (χ2[1] = 13.0, p < .001), and hepatitis C virus infection (χ2[1] = 9.8, p = .002). No other variables listed in Table 1 were significantly different between serostatus groups (all ps > .10).

All variables in Table 1 that differed by HIV serostatus were subsequently evaluated as possible covariates for inclusion in the logistic regressions examining the association between HIV serostatus and the neurocognitive criteria (i.e., DSM-5, Frascati, Gisslén). Years of education and POMS total mood disturbance scores also were associated with all three neurocognitive criteria (all ps < .05). In addition, lifetime history of Major Depressive Disorder was associated with both the Frascati and Gisslen neurocognitive criteria (all ps < .05). Finally, Hepatitis C virus was related to Gisslen criteria (χ2[1] = 4.7, p = .030). Thus, these variables were respectively included as covariates in the subsequent models with HIV serostatus predicting neurocognitive impairment as defined by each of the criteria.

Additionally all HIV disease characteristics described in Table 1 were evaluated in relation to neurocognitive status (i.e., impaired or not impaired) across the three criteria among HIV+ participants. Results of individual chi-squared analyses showed no differences in HIV disease variables between participants who met neurocognitive impairment requirements and those who did not meet neurocognitive impairment requirements for any of the diagnostic approaches (all ps > .09).

Neurocognitive Impairment Criteria Differences Across HIV Serostatus Groups

DSM-5 Neurocognitive Impairment Criteria

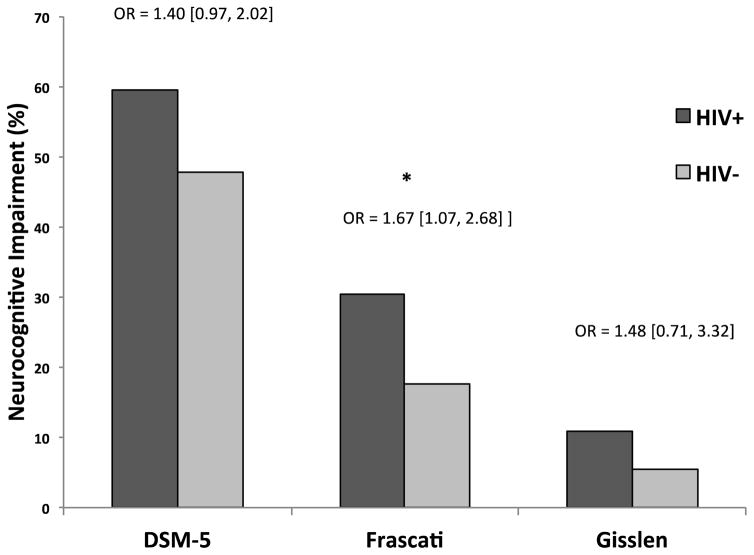

The overall model of HIV serostatus predicting DSM-5-defined neurocognitive impairment was statistically significant (χ2[3] = 17.8, p < .001, R2=.02). Within this model, HIV serostatus was a predictor of DSM-5 neurocognitive impairment at trend level (χ2[1] = 3.3, p = .069, OR = 1.4 [1.0, 2.0]) (see Figure 1). HIV+ individuals were (1.4 times) more likely to be designated as neurocognitively impaired based on DSM-5 criteria compared to HIV- individuals, independent of POMS (p = .006) and years of education (p = .14).

Figure 1.

Neurocognitive impairment differences across HIV serostatus groups using DSM-5, Frascati, and Gisslén neurocognitive criteria. Odds ratios (OR) reflect the increased likelihood for neurocognitive impairment given HIV+ serostatus.

Frascati Neurocognitive Impairment Criteria

The overall model of HIV serostatus predicting Frascati-defined neurocognitive impairment was statistically significant (χ2[4] = 28.3, p < .001, R2=0.05). Within this model, HIV serostatus was a significant predictor of Frascati neurocognitive impairment (χ2[1] = 4.9, p = .027, OR = 1.7 [1.1, 2.7]) (see Figure 1). HIV+ individuals were 1.7 times more likely to be designated as neurocognitively impaired based on Frascati criteria compared to HIV- individuals independent of POMS (p = .017), years of education (p = .008), and MDD (p = .37).

Gisslen Neurocognitive Impairment Criteria

The overall model of HIV serostatus predicting Gisslén-defined neurocognitive impairment was statistically significant (χ2[5] = 31.5, p < .001, R2=.10). Within this model, HIV serostatus failed to reach statistical significance as an independent predictor of Gisslén-defined neurocognitive impairment (χ2[1] = 1.0, p = .314, OR = 1.5 [0.7, 3.3]) (see Figure 1). Only years of education was a significant independent predictor of Gisslen-defined neurocognitive impairment in this model (p < .001).

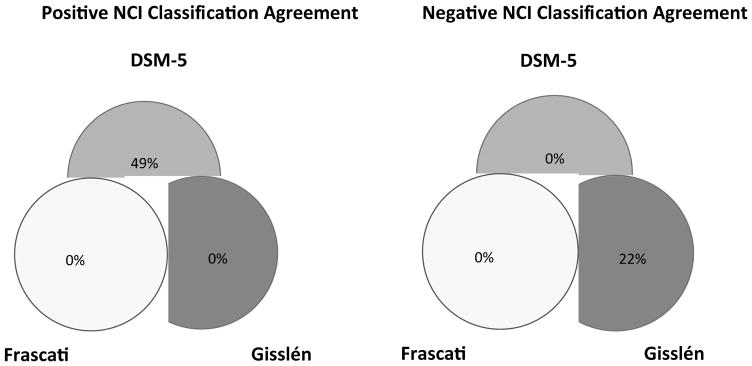

Agreement of Neurocognitive Impairment Across Diagnostic Criteria

Analyses examining the agreement of the three neurocognitive criteria across our HIV+ sample (N=361) showed that the DSM-5 and Frascati criteria agreed on 71% of observations, with a moderate kappa of 0.46 (95% CI = .39, .53); Frascati and Gisslen showed agreement on 80% of observations, with a moderate kappa of 0.43 (95% CI = .34, .53); and DSM-5 and Gisslen criteria showed agreement on 46% of observations, with a poor kappa of .15 (95% CI = .10, .20).

Figure 2(A) shows the percentage of positive diagnostic reliability and Figure 2(B) shows the percentage of negative diagnostic reliability across the three criteria for identifying individuals with HAND in within our entire sample of HIV+ individuals. Positive diagnostic reliability refers to the percent of individuals that are indicated as having neurocognitive impairment across the three diagnostic criteria. Among those designated as having HAND in at least one diagnostic criteria (n = 215), there was 18% positive agreement across the three diagnostic criteria, and 33% positive agreement between DSM-5 and Frascati criteria. In contrast, 49% of the HIV+ sample met criteria only for DSM-5. Negative diagnostic reliability refers to the percent of individuals that are indicated as not having neurocognitive impairment across the three diagnostic criteria. Among those designated as not having HAND in at least one diagnostic criteria (n = 322), there was 45% negative agreement across the three diagnostic criteria, 33% negative agreement between Gisslén and Frascati criteria, while 22% of the HIV+ sample were classified as not having neurocognitive impairment by Gisslén criteria alone.

Figure 2.

Percentage of positive diagnostic reliability 2(A) and percentage of negative diagnostic reliability 2(B) across the three criteria with the entire HIV+ sample. NCI = Neurocognitive Impairment.

Neurocognitively Impaired (DSM-5 Only, Both DSM-5 and Frascati, or DSM-5, Frascati, and Gisslén Criteria) Sample Characteristics

We were interested in determining whether there were any demographic, psychiatric, medical, or HIV disease characteristic differences that might otherwise explain difference in rates of HAND for HIV+ subgroups characterized as being neurocognitively impaired in one (i.e., DSM-5) or overlapping (i.e., DSM-5+Frascati; DSM-5+Frascati+Gisslén) criteria (i.e., positive classification agreement groups). As shown in Figure 2(A), we performed separate one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or non-parametric equivalent tests using the 3-level (DSM-5 only, DSM-5+Frascati, DSM-5+Frascati+Gisslén) positive diagnostic criteria agreement as the predictor variable and each of the demographic, psychiatric, medical, or HIV disease characteristic variables listed in Table 1 as the outcome variable for each test while correcting for multiple comparisons using a false discovery rate. Pair-wise comparisons for significant omnibus one-way ANOVAs were conducted between the 3 subgroups using Tukey honest significance test (HSD). As shown in Table 3, using the False Discovery Rate, no variables differed significantly across the three positive diagnostic agreement groups.

Table 3.

Description of neuropsychological measures within the assessed cognitive domains across the three diagnostic criteria.

| Neuropsychological Domains & Measures | HIV− (n = 196) | HIV + (n = 353) | p | Cohen’s d | Demographics Adjusted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attention Domain | |||||

| Digit Span | 53.67 (9.3) | 50.22 (9.3) | < .0001 | 0.37 | Age |

| CVLT-II Trial 1 | 49.20 (13.4) | 44.9 (11.8) | .0001 | 0.34 | Sex, Age |

| Executive Domain | |||||

| Tower of London Moves | 48.54 (10.8) | 49.12 (11.7) | .567 | −0.05 | Age |

| Actions* | 47.26 (9.5) | 45.79 (9.3) | .076 | 0.16 | Ed. |

| Trail Making Test Part B | 51.08 (10.8) | 49.66 (11.8) | .163 | 0.13 | Race, Sex, Age, Ed. |

| Learning Domain | |||||

| CVLT-II Trial 1–5 | 54.96 (11.5) | 50.78 (10.7) | <.0001 | 0.38 | Sex, Age |

| LM1 Total | 55.65 (11.4) | 51.10 (10.8) | <.0001 | 0.41 | Age |

| Memory Domain | |||||

| LM2 Total | 57.61 (11.1) | 52.39 (11) | <.0001 | 0.47 | Age |

| CVLT-II Long Delay Free Recall | 52.04 (10.7) | 48.13 (11.8) | .0001 | 0.35 | Sex, Age |

| Speed of Processing Domain | |||||

| Tower of London Execution Time | 47.58 (9.6) | 46.89 (10) | .427 | 0.07 | Age |

| Trail Making Test Part A | 51.77 (10) | 50.23 (10.7) | .093 | 0.15 | Race, Sex, Age, Ed. |

| Motor Domain | |||||

| Grooved Peg Board (Dom) | 48.77 (10.3) | 47.42 (10.8) | .156 | 0.13 | Race, Sex, Age, Ed. |

| Grooved Peg Board (Non Dom) | 48.71 (11.2) | 47.35 (10.6) | .160 | 0.13 | Race, Sex, Age, Ed. |

| Language Domain** | |||||

| Boston Naming Test | 49.54 (12.5) | 49.63 (12) | .930 | −0.01 | Age, Ed. |

Note. Data are presented as mean T-scores (standard deviation) for each study group. Digit Span subtest from Wechsler Memory Scale, 3rd edition; CVLT-II = California Verbal Learning Test, 2nd edition; LM 1 & 2 = with Logical Memory I subtest from the WMS-III.

Actions were included within the executive domain for only Frascati and Gisslén neurocognitive criteria.

The Language domain was included only in the DSM-5 criteria comprised of the Boston Naming Test and Actions.

Neurocognitive Impairment Criteria Predicting Everyday Functioning Outcomes

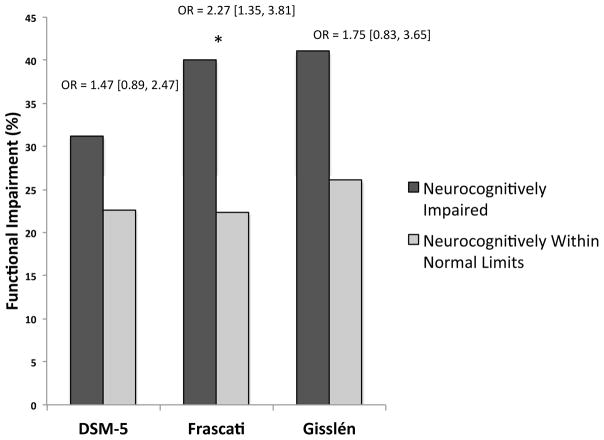

As shown in Figure 3, each of the three neurocognitive criteria were examined as predictors of a dichotomous global everyday functioning composite along with a priori derived covariates MDD, AIDS status, and cognitive reserve composite (i.e., education, WTAR) predicting the dichotomous global everyday functioning composite (NB. using a continuous outcome yielded an identical pattern of results as described below for each of the diagnostic criteria predictors).

Figure 3.

DSM-5, Frascati, and Gisslén neurocognitive impairment predicting manifest everyday functioning outcomes in the HIV+ sample (N = 361). Odds ratios (OR; [95% confidence interval]) reflect the increased likelihood for functional impairment given neurocognitive impairment as defined by each system.

DSM-5 Neurocognitive Impairment Criteria

The overall model of DSM-5-defined neurocognitive impairment predicting the dichotomous global everyday functioning composite was statistically significant (χ2[4] = 31.0, p < .001, R2=.07). However, DSM-5-defined neurocognitive impairment failed to reach significance as an independent predictor of everyday functioning (χ2[1] = 2.2, p = .139, OR = 1.5 [0.9, 2.5]. Lifetime MDD (χ2[1] = 20.5, p < .001, OR = 3.4 [2.0, 5.9]), and AIDS status (χ2[1] = 4.91, p = .027, OR = 1.75 [1.1, 2.9]) were the only independent predictors of everyday functioning impairment in this model, while cognitive reserve was not (p > .10; see Figure 3).

Frascati Neurocognitive Impairment Criteria

The overall model of Frascati-defined neurocognitive impairment predicting the dichotomous global everyday functioning composite was statistically significant (χ2[4] = 38.42, p < .001, R2=.09). Within this model, Frascati-defined neurocognitive impairment was a significant independent predictor of everyday functioning (χ2[1] = 9.7, p = .002, OR = 2.27 [1.4, 3.8]), alongside lifetime MDD (χ2[1] = 19.1, p < .001, OR = 3.3 [2.0, 5.8]) and AIDS status (χ2[1] = 5.3, p = .020, OR = 1.8 [1.1, 3.0]). Results indicate that individuals with Frascati-defined neurocognitive impairment were 2.3 times more likely to be designated as impaired on the everyday functioning composite (see Figure 3).

Gisslén Neurocognitive Impairment Criteria

The overall model of Gisslén-defined neurocognitive impairment predicting the dichotomous global everyday functioning composite was statistically significant (χ2[4] = 31.0, p < .001, R2=0.07). Within this model, Gisslén-defined neurocognitive impairment failed to reach significance as an independent predictor of everyday functioning impairment (χ2[1] = 2.2, p = .134, OR = 1.8 [0.8, 3.7]. Only lifetime MDD (χ2[1] = 20.2, p < .001, OR = 3.4 [1.1, 5.9]) and AIDS status (χ2[1] = 5.1, p = .024, OR = 1.8 [1.1, 2.9]) were independent predictors of everyday functioning impairment (see Figure 3).

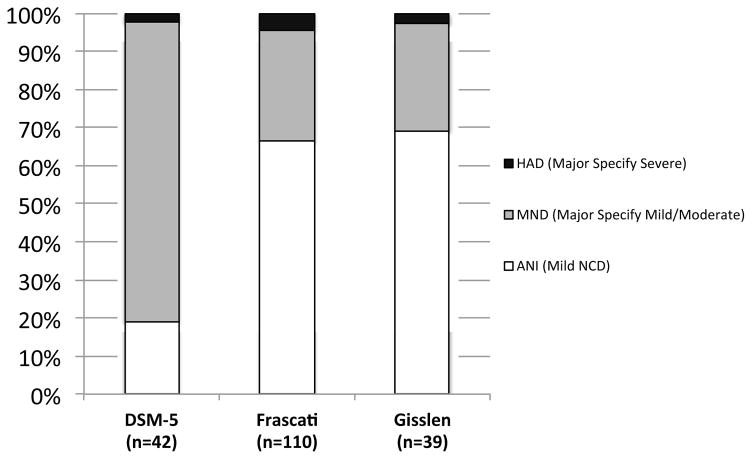

Syndromic HAND Across Diagnostic Criteria

Figure 4 displays the percentage of neurocognitively impaired HIV+ individuals who met criteria for moderate and severe levels of everyday functioning impairment across the three diagnostic schemes. Among HIV+ individuals with evidenced neurocognitive impairment and reported cognitive complaint as defined by DSM-5 neurocognitive criteria (n=42), 79% (n=33) met criteria for moderate levels of everyday functioning impairment and 2% (n=1) of individuals met criteria for severe levels of everyday functioning impairment. Among HIV+ individuals with Frascati-defined neurocognitive impairment (n=110), 29% (n=32) of individuals met criteria for MND and 5% (n=5) met criteria for HAD. Among HIV+ individuals with Gisslén-defined neurocognitive impairment (n=39), 28% (n=11) of individuals met criteria for MND and 3% (n=1) met criteria for HAD.

Figure 4.

Rates of syndromic HAND across DSM-5, Frascati, and Gisslén diagnostic criteria across the entire HIV+ sample (except DSM-5, which is across individuals that met DSM-5 diagnostic criteria including cognitive complaint of neurocognitive problems).

Individual pairwise omnibus chi-square analyses were conducted to compare of rates of specific diagnostic severity (i.e., ANI [mild in the case of DSM-5], MND, HAD) across the diagnostic criteria, which revealed significant differences across all three groups (all ps < .001). Among HIV-seropositive individuals who have been classified as neurocognitively impaired for the respective diagnostic severity criteria, rates of a diagnosis of ANI (Mild HAND in the case of the DSM-5) are significantly higher using the Gisslén (χ2[1] = 45.1, p < .0001) or the Frascati diagnostic severity criteria (χ2[1] = 39.8, p < .0001) compared to using the DSM-5. There were no significant difference in the rates of ANI diagnoses between Gisslén and Frascati diagnostic criteria (χ2[1] = 0.4, p =.5227). Diagnoses of MND (Major specified mild and moderate in the case of the DSM5) were significantly higher using the DSM-5 diagnostic manual compared to both the Frascati (χ2[1] = 44.0, p < .0001) and the Gisslén diagnostic criteria (χ2[1] = 45.9, p < .0001). There was no significant difference in the rates of MND diagnoses between Gisslén and Frascati diagnostic criteria (χ2[1] = 0.04, p =.836). Chi-square comparisons show that rates of HAD diagnoses (Major HAND specified severe in the case of DSM-5) did not differ among the three diagnostic criteria (all ps > .10).

Longitudinal Changes Across the 3 Diagnostic Criteria

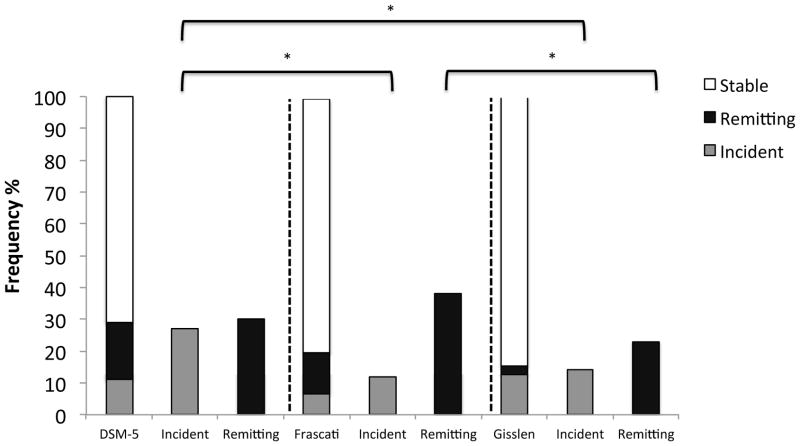

Figure 5 shows the rates of stable, incident and remitting neurocognitive disorders across the three diagnostic criteria over the test-retest interval (stacked bar charts; N = 118). Additionally, Figure 5 displays the frequency of these classifications (i.e., stable, incident, remitting) across the respective neurocognitive criteria (secondary bar charts; n’s varied to reflect the individual criteria). Omnibus pairwise analyses comparing the overall rates of neurocognitive classifications (i.e., a three-level variable for each criteria; N= 118) showed significant differences in the overall rates of classification between Frascati and DSM-5 (χ2[1] = 18.46, p = .001) as well as Frascati and Gisslén (χ2[1] = 29.9, p < .0001) criteria. There were no significant differences in the classification rates between DSM-5 and Gisslén requirements (p = .10).

Figure 5.

Stacked bar charts show the rates of incident, stable, and remitting neurocognitive disorders for the total longitudinal HIV+ sample (N=118) across the three diagnostic criteria. In the secondary bar charts, the percentage of incident and remitting neurocognitive disorders are displayed using only those individuals who would were eligible for a change in cognitive status (i.e., incident cases for only persons who were neurocognitively normal at baseline and remitting cases for only those individuals who were neurocognitively impaired at baseline).

One sample chi-square tests directly comparing the frequency of incident, stable, and remitting neurocognitive disorders across diagnostic criteria (i.e., Frascati, Gisslén, or DSM-5) were conducted. Among those who were within normal limits at baseline by their respective diagnostic criteria (DSM-5 n=48, Frascati n = 78, Gisslén n =105), results revealed significantly higher rates of incident neurocognitive disorder when the DSM-5 criteria were applied compared to both Frascati (χ2[1] = 8.6, p = .003) and Gisslén (χ2[1] = 5.3, p = .021) guidelines. There were no significant differences in rates of incident neurocognitive disorder between Frascati and Gisslén criteria (p = .48). Results of analyses comparing rates of remitting neurocognitive disorder among individuals who were designated neurocognitively impaired at baseline by their respective criteria (DSM-5 n = 70, Frascati n = 40, Gisslén n =13), showed no significant differences in frequency between the DSM-5 and Frascati or DSM-5 and Gisslén criteria (all ps > .10). However, results indicated significantly lower rates of remitting neurocognitive disorder when using Gisslén criteria compared to Frascati requirements (χ2[1] = 4.2, p = .04). Application of DSM-5 requirements evidenced significantly lower rates of stable neurocognitive status assignment (either not impaired across test-retest interval, or impaired at both test and retest interval; N= 118) compared to both Frascati (χ2[1] = 4.8, p = .03) and Gisslén (χ2[1] = 14.0, p = .0002) criteria. However designation of stable status did not differ between Gisslén and Frascati neurocognitive guidelines (p = .14).

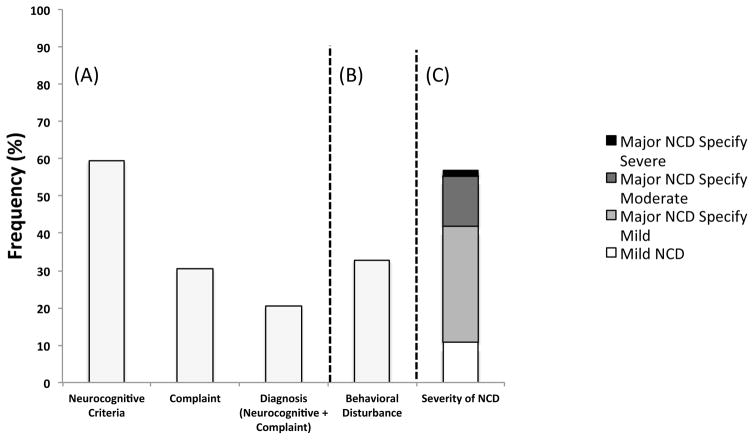

Sample Characteristics of HAND Characterized by DSM-5

The above analyses focused only on the neurocognitive (and functional impairment where applicable) components of the diagnostic criteria. However, one unique aspect of DSM-5 diagnostic criteria is that it requires subjective cognitive complaint by the individual (or on the behalf of the individual) in addition to evidence of objective neurocognitive impairment, whereas Frascati and Gisslén rely exclusively on objective neuropsychological measures as the indicator for cognitive impairment. Figure 6(A) shows the prevalence of impairment across varying DSM-5 diagnostic considerations. Results of chi-square analyses show that the addition of the cognitive complaint criterion to neuropsychological criteria results in significantly fewer neurocognitive disorder designations compared to meeting requirements for DSM-5 neuropsychological impairment alone (χ2[1] = 261.3, p < .001). For descriptive purposes, Figure 6(B) shows the proportion of individuals that met criteria for behavioral disturbance specifier across the HIV+ sample with neurocognitive disorder diagnosis (including complaints; n=74). Figure 6(C) shows the rate of mild, moderate, and severe specifiers among HIV+ with neurocognitive disorder diagnosis (including complaints; n=74).

Figure 6.

Frequency of impairment across neurocognitive criteria only, cognitive complaint only, and diagnosis (neurocognitive and complaint) criteria (A) among HIV+ participants (N = 361); frequency of behavioral disturbance among individuals with DSM-5 neurocognitive disorder and complaint (B; n = 73) and severity rating of DSM-5 neurocognitive disorder diagnosis among HIV+ individuals who met DSM-5 neurocognitive and complaint criteria (C; n = 74).

DSM-5 Neurocognitive Criteria with Complaint Across Serostatus Groups

Since sole application of the DSM-5 neurocognitive criteria evidenced high prevalence of impairment, showed no observed difference in rates of impairment serostatus groups (see Figure 1), and did not completely adhere to the DSM diagnostic criteria as written, we also examined DSM-5 differences across HIV serostatus groups when both neurocognitive and subjective complaint criteria were considered. To do so, we examined all covariates that differed across HIV serostatus groups as listed in Table 1 and also differed across DSM-5 diagnosis groups. Of these the variables, only Lifetime MDD differed between both HIV-serostatus groups and DSM-5 diagnosis groups. The overall logistic regression model with HIV serostatus groups predicting DSM-5 neurocognitive impairment with complaint was significant (χ2[1] = 39.1, p < .001, R2=.08). Further, results show that HIV serostatus was a significant independent predictor of DSM-5 neurocognitive impairment with complaint (χ2[1] = 18.8, p < .001, OR = 5.4 [2.7, 12.4]), such that HIV positive individuals were over 5 times more likely to be classified as having a DSM-5 neurocognitive impairment with complaint diagnosis compared to their HIV-seronegative counterparts.

DSM-5 Neurocognitive Criteria with Complaint Predicting Everyday Functioning Outcomes

DSM-5 neurocognitive criteria with complaint was examined as a predictor of the dichotomous global everyday functioning composite used above along with a priori derived covariates MDD, AIDS status, and cognitive reserve composite (i.e., education, WTAR). The overall model of DSM-5-defined diagnoses predicting the dichotomous global everyday functioning composite was statistically significant (χ2[4] = 43.0, p < .001, R2=0.10). DSM-5 neurocognitive impairment with complaint diagnosis was a significant independent predictor of everyday functioning (χ2[1] = 14.4, p < .001, OR = 2.9 [1.7, 5.1]. Lifetime MDD (χ2[1] = 18.2, p < .001, OR = 3.3 [1.9, 5.7]) and AIDS status (χ2[1] = 4.7, p = .030, OR = 1.7 [1.1, 2.9]) were all independent predictors of everyday functioning impairment in this model, while cognitive reserve failed to reach significance as an independent predictor (p > .10).

Longitudinal Changes of DSM-5 Neurocognitive Impairment with Complaint

The rates of stable, incident, and remitting DSM-5 neurocognitive impairment with complaint over the test-retest interval were also investigated. Omnibus pairwise analyses comparing the overall rates of neurocognitive classifications (i.e., a three-level variable [stable, incident, or remitting] for each criteria) revealed no significant differences in the overall classification rates between the DSM-5 with complaint and Gisslén or Frascati criteria (all ps > .10).

In parallel to analyses investigating frequency of individual classification assignment above, examinations of differences in the rates of stable, incident, and remitting neurocognitive disorders across the criteria using DSM-5 with complaint were also conducted. Among those who were within normal limits at baseline by their respective diagnostic criteria (DSM-5 with complaint n=88, Frascati n = 78, Gisslén n =105) analyses revealed lower rates of stable neurocognitive status when using the DSM-5 with complaint criteria compared to Gisslén (χ2[1] = 8.6, p = .004), however there were no differences in rates of stable assignment between DSM-5 with complaint and Frascati neurocognitive requirements (p > .10). Results show no differences in the rates of incident neurocognitive disorder assigned using DSM-5 with complaint compared to Gisslen or Frascati criteria (all ps > .10). Regarding remitting neurocognitive disorder classifications, DSM-5 with complaint evidenced a significantly higher rate of remitting neurocognitive impairment assignment compared to the Gisslén criteria (χ2[1] = 10.3, p = .001), however, there were no significant differences among rates of remitting neurocognitive status between DSM-5 with complaint and Frascati guidelines (ps > .10).

We were also interested in how the rates of neurocognitive classification changed when applying the DSM-5 with complaint criteria in comparison to rates when using the DSM-5 neurocognitive requirements alone. An omnibus pairwise analysis comparing the overall rates of neurocognitive diagnostic classifications (i.e., a three-level variable [stable, incident, or remitting]) revealed significant differences in the overall rates of classification between DSM-5 and DSM-5 with complaint criteria (χ2[1] = 23.8, p < .0001). One sample chi-square tests directly comparing the frequency of neurocognitive status classification show that while there were no differences in rates of stable neurocognitive status assignment (p > .10), there were significantly lower rates of incident neurocognitive disorders when using the DSM-5 with complaint criteria compared to DSM-5 neurocognitive guidelines alone (χ2[1] = 23.8, p < .0001). However, DSM-5 with complaint also evidence greater rates of remitting disorders compared to DSM-5 neurocognitive criteria alone (χ2[1] = 5.2, p = .02).

Discussion

The current study sought to compare the frequency, reliability, and the functional implications of three methodologies for diagnosing HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Consistent with study hypotheses and previous findings (Su et al., 2015), results showed significantly lower rates of neurocognitive impairment when utilizing the Gisslén et al., (2011) criteria compared to the Frascati criteria (Antinori et al., 2007). Additionally, the DSM-5 neurocognitive diagnostic guidelines were more liberal than both the Gisslén and Frascati criteria for determining neurocognitive impairment. Further, the overall agreement across the three diagnostic criteria was poor, and the rates of HAND diagnosis among the three schemes revealed discrepant stability of classifications over the 14-month test-retest period. In regards to functional outcomes, the current study suggests that only the Frascati neurocognitive criteria are predictive of everyday functioning impairment. The implications of these findings are discussed below.

Across the three schemes, HAND diagnosis was most prevalent when using the DSM-5 neurocognitive guidelines. In fact, nearly 60% of our HIV+ sample was classified as impaired by way of DSM-5 criteria. Although high rates of false positives have been reported using the Frascati requirements (e.g., Gisslen et al., 2011; Meyer et al., 2013), we observed a higher HAND prevalence using the DSM-5 criteria as compared to the Frascati. Indeed, the reported rate of neurocognitive impairment by way of Frascati criteria is consistent with previous studies that have applied this diagnostic scheme conservatively using average domain scores rather than individual tests scores (e.g., Morgan et al., 2012). Also consistent with previous investigations (e.g., Su et al., 2015), the lowest rates of neurocognitive impairment were produced from application of the Gisslén criteria, which echoed the central argument for modifying the Frascati requirements (Gisslén et al., 2011). While it may be argued that the nature of higher threshold for neurocognitive impairment used in the Gisslén criteria account for this finding, that argument would not justify the failure of guidelines used to determine HIV- associated impairment to discriminate between dysfunction among HIV-positive and HIV- negative individuals. Thus, the results of the current study suggest that the use of highly conservative cutpoints for impairment like those used in the Gisslen criteria may reduce sensitivity to HIV-serostatus. When DSM-5 criteria were applied, similar rates of neurocognitive impairment were observed among HIV-seronegative and HIV-seropositive participants. Notably, HIV-serostatus was a significant predictor of neurocognitive impairment classification for only the Frascati requirements (trend level for the DSM-5). This finding suggests that the Frascati criteria may be more adept at characterizing cognitive impairment associated with HIV, compared to the other diagnostic methodologies. Indeed, the Frascati criteria are by far the most widely used nosology among HIV researchers and clinicians, thus Frascati guidelines have the largest empirical foundation of the three assessed schemes.

Investigations of reliability among the three neurocognitive criteria reveal an 80% agreement of impairment across the Frascati and Gisslen schemes, a 71% rate of agreement between Frascati and the DSM-5, and a 46% rate of agreement between the Gisslen and DSM-5 schemes. The moderate agreement across Frascati and Gissén was likely due, in part, to the similarities in measures used to determine neurocognitive impairment (i.e., same domains and tests were evaluated using different thresholds). The high rate of agreement across the Frascati and DSM-5 criteria may reflect similarities in the use of more lenient thresholds for impairment (i.e., 1sd < mean). While the less than 50% agreement rate across Gisslen and DSM-5 neurocogntive criteria likely represents the comparison of a more liberal standard (DSM-5) to that of a more conservative guidelines (Gisslen). Interestingly, across all three criteria the positive classification agreement rate was only 18% indicating that fewer than 1 in 5 individuals who were classified as neurocognitively impaired by one set of diagnostic criteria were also designated impaired by the others. Similarly, agreement of negative classification rate across the criteria was also poor showing consensus across criteria for less than half (45%) of the individuals characterized as not neurocognitively impaired. This lack of consistency led to individuals being classified as neurocognitively impaired (usually by DSM-5) or neurocognitively normal (usually by Gisslen) by only one criteria. These results are displayed in Figures 2A and 2B and demonstrate the overly inclusive neurocognitive impairment standards of the DSM-5 and the reduced sensitivity to HIV-associated impairment of the Gisslén’s strict criteria thresholds.

Perhaps the most important contributions this study lends to extant literature are the findings regarding independent predictions of functional outcomes. Dysfunction related to HAND has been reported in a range of important activities of daily living, but this is the first study to compare the criteria of neurocognitive impairment against an external, diagnostically relevant clinical outcome. Results indicate that only the neurocognitive impairment guidelines outlined by Frascati significantly relate to everyday functioning impairment. Specifically, individuals with Frascati-defined neurocognitive impairment were 2.3 times more likely to demonstrate everyday functioning impairment compared to seronegatives. The use of strict cutpoints, such as those used in Gisslén criteria, may underestimate the risk of important functional outcomes, such as employment and activities of daily living difficulties. Similarly, individuals are classified as having a syndromic form of HAND when using the DSM-5 (79%) at a rate more than double that of Frascati (33.6%) or the Gisslén criteria (30.7%), suggesting that the DSM-5 neurocognitive requirements may overestimate the prevalence of functional deficits in HAND among HIV- positive individuals. This is an important consideration across criteria as studies have shown that while HIV infected individuals attribute their functional problems to cognitive problems (Obermeit et al., 2016), approximately 50% of individuals perform within normal limits on well validated, comprehensive test batteries (e.g., Heaton et al., 2004). Thus, the ability of a diagnostic measure to accurately predict functional difficulties attributed to neurocognitive deficits is important to gaining a complete understanding of the severity of the HAND.

Another novel contribution of the current study is the examination of the three HAND criteria over a one-year time period. Prior studies have investigated the incidence of neurocognitive impairment using the Frascati criteria (e.g., Sheppard et al., 2015), however, there have been no studies that examine the DSM-5 guidelines from a longitudinal perspective and additionally, no studies have directly compared the rates of observed changes (or lack thereof) across these diagnostic guidelines. Results show similar rates of both stable classification and incident neurocognitive disorder between the Frascati and Gisslén criteria. Notably however, the DSM-5 neurocognitive impairment criteria were associated with elevated rates of incident neurocognitive disorder classifications and correspondingly lower rates of stable neurocognitive status assignment at one-year follow-up. This pattern likely reflects the overly inclusive cast of the DSM-5 guidelines previously observed in the reliability analyses. While one may think that the liberal inclusivity of the DSM-5 requirements may result in high rates of remitting disorders, our findings show no significant differences in rates of remission between DSM-5 and the other two criteria. This is likely due to the fact that if the liberal criteria had determined an individual to impaired at time one, those same guidelines would still classify the individual as impaired at time 2 unless there was measurable improvement over the delay interval. In contrast, the current study findings that Gisslén requirements evidenced significantly lower remitting neurocognitive disorders compared to those of Frascati, reflect the conservative nature of the Gisslén criteria; once an individual has met the stringent neurocognitive criteria for impairment by way of the Gisslén, it is less likely that the individual would demonstrate a level of improvement needed to be considered neurocognitively healthy over the test-retest interval. Such findings are important considerations when conducting longitudinal work. These results suggest that the Frascati and Gisslén criteria may be more appropriate to conduct longitudinal investigations as these guidelines are shown to be more stable over time and further, the findings indicate that Frascati criteria may strike a complementary balance between the liberal requirements of the DSM-5 and the conservative guidelines of the Gisslén diagnostic scheme.

While results examining the DSM-5 neurocognitive guidelines generally suggest an overly inclusive model and possible overestimation of HAND, a very different picture emerged when both cognitive criteria and complaint were considered. Not only was the percentage of individuals who qualified as impaired drastically reduced when both cognitive and complaint criteria were taken into account, but results also show that HIV serostatus was a significant predictor of DSM-5 with complaint diagnosis. Further, when considering both neurocognitive criteria and complaint, the DSM-5 diagnosis was an independent and strong predictor of everyday functioning. Findings also indicate that considering both DSM-5 cognitive criteria with complaint guidelines lead to improved reliability. Specifically, there were no longer differences in the rates of stable neurocognitive status assignment between Frascati and the DSM-5, and the rates of incident impairment were comparable across the three criteria when both cognitive and complaint DSM-5 requirement were considered. Experimenters and clinicians who are naïve to working with HIV may consider the difference in prevalence that including complaint affords. As previous investigations as noted differences in the application of diagnostic criteria (e.g., Su et al., 2015), this finding also highlights the importance of understanding the components involved in diagnoses across researchers and clinicians alike.

The overall sample was largely comprised of white, educated men from an urban setting. Thus, the external validity and generalizability of findings in broader national and international settings remains to be determined. Although the longitudinal group was limited to 14-months between initial and follow-up testing, it should be noted that previous studies have also observed changes in neurocognitive functioning over a one-year interval (e.g., Seider et al., 2014). Another possible limitation inherent to the longitudinal component of the current study is the interference of practice effects as confounding variables in the outcome of incident, remitting, and stable neurocognitive disorder diagnosis. However, it should be noted that it is unlikely that any between-group findings were a product of multiple test administrations as there is no reason to expect that these effects would be limited to one HIV status group or one specific set of diagnostic criterion.

Despite these limitations, results of the current study extend extant literature in three substantial ways. First, findings offer information concerning the ability of each scheme’s neurocognitive criteria to predict everyday functioning outcomes, which have been shown to be associated with important downstream outcomes such as functional independence and mortality. Second, the current study evaluated the stability of HAND diagnoses across three sets of diagnostic criteria over the longitudinal period of one year. Lastly, results provide novel evidence regarding the utility of the DSM-5 HAND diagnostic criteria that have, thus far, not been examined. Taken together, findings provide a substantial amount of valuable information to consider when choosing a method to determine a HAND diagnosis. For example, more liberal guidelines may be preferred when selecting participants for a noninvasive treatment whereas conservative requirements may better suit selection of candidates for more aggressive HAND treatment procedures. Further, guidelines that offer increased stability over time may be selected for use in longitudinal investigations of HAND. Finally, criteria that have been shown to effective at predicting functional consequences may be chosen to evaluate disease severity in regards to benefits such as insurance and disability. Still, as consistent use of the same diagnostic classification method across research and clinical settings may enhance both communication and understanding of HIV associated neurocognitive deficits, future studies are needed to replicate these findings and to further assess the utility of these criteria in practice. Moreover, future studies should aim to identify gold standard biological markers (e.g., neuropathology) and clinical outcomes associated with specific diagnostic criteria.

Table 4.

Demographic, psychiatric, medical, and HIV disease characteristics among HIV+ individuals who meet criteria for one or more diagnostic schemes.

| DSM-5 Only (n=105) | DSM-5+Frascati (n=71) | All 3 Criteria (n=39) | False Discovery Rate α | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 44.7 (1.1) | 45.9 (1.4) | 44.6 (1.9) | .0441 | .796 |

| Education (years) | 13.5 (0.2) | 13.6 (0.3) | 12.1 (0.4) | .0029 | .004 |

| Employment Status (% employed) | 75.2% | 76.1% | 69.2% | .0389 | .716 |

| Gender (% men) | 87.6% | 84.5% | 82.5% | .0382 | .664 |

| Ethnicity (% Caucasian) | 56.1% | 47.8% | 61.5% | .0118 | .341 |

| Verbal IQ (WTAR) | 101.3 (1.9) | 99.4 (1.4) | 95.9 (1.9) | .0059 | .058 |

| POMS Total Mood Disturbance | 58.5 (3.8) | 65.8 (4.6) | 73.1 (6.2) | .0088 | .119 |

| Major Depression † | 55.7% | 62.8% | 66.6% | .0235 | .418 |

| Generalized Anxiety † | 17.3% | 11.5% | 15.3% | .0324 | .579 |

| Substance Dependence ‡ | 54.2% | 54.9% | 61.5% | .0412 | .724 |

| Hepatitis C Virus | 18.6% | 16.1% | 25.6% | .0265 | .495 |

| HIV | |||||

| AIDS | 60.0% | 55.7% | 51.2% | .0353 | .622 |

| Duration of Infection (months) | 166.2 (9.7) | 158.9 (12.2) | 140.4 (15.9) | .0206 | .392 |

| CD4 Count | 571.2 (30.1) | 564.1 (35.8) | 594.4 (48.3) | .0500 | .878 |

| Nadir CD4 Count | 207.1 (19.0) | 218.2 (23.1) | 259.0 (31.2) | .0176 | .367 |

| ARV Status | 87.6% | 84.5% | 84.6% | .0471 | .810 |

| Plasma RNA detectable in those prescribed cART | 19.6% | 28.9% | 24.3% | .0147 | .366 |

| 13.0% | 18.9% | 12.5% | .0294 | .572 | |

Note. Data are presented as means (standard error) or as percentages. POMS = Profile of Mood States; AIDS = Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome; CD4 = Cluster of Differentiation 4; ART = antiretroviral therapy.

Includes current and lifetime diagnoses.

Any lifetime diagnosis of dependence on alcohol or illicit substance.

Acknowledgments

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest related to this work. This study was supported by NIH grants R01-MH073419 and P30-MH62512. The authors are grateful to the UC San Diego HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program (HNRP) Group (I. Grant, PI) for their infrastructure support of the parent R01. In particular, we thank Donald Franklin, Dr. Erin Morgan, Clint Cushman, and Stephanie Corkran for their assistance with data processing, Marizela Verduzco for her assistance with study management, Drs. Scott Letendre and Ronald J. Ellis for their assistance with the neuromedical aspects of the parent project, and Dr. J. Hampton Atkinson and Jennifer Marquie Beck and their assistance with participant recruitment and retention. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, nor the United States Government. The authors thank the study volunteers for their participation.

References

- Al-Khindi T, Zakzanis KK, Van Gorp WG. Does antiretroviral therapy improve HIV-associated cognitive impairment? A quantitative review of the literature. JINS. 2011;17(6):956. doi: 10.1017/S1355617711000968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Washington, DC: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, Brew BJ, Byrd DA, Cherner M, Clifford DB, Cinque P, Epstein LG, Goodkin K, Gisslen M, Grant I, Heaton RK, Joseph J, Marder K, Marra CM, McArthur JC, Nunn M, Price RW, Pulliam L, Robertson KR, Sacktor N, Valcour V, Wojna VE. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2007;69:1789–1799. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000287431.88658.8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Army Individual Test Battery. Manual of directions and scoring. Washington, DC: War Department, Adjutant General’s Office; 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Chan P, Brew BJ. HIV associated neurocognitive disorders in the modern antiviral treatment era: prevalence, characteristics, biomarkers, and effects of treatment. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2014;1(3):317–324. doi: 10.1007/s11904-014-0221-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culbertson WC, Zillmer EA. The Tower of London, Drexel University, research version: examiner’s manual. North Tonawanda: Multi-Health Systems; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Delis DC, Kramer JH, Kaplan E, Ober BA. The California verbal learning test. 2. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi NS, Skolasky RL, Peters KB, Moxley RT, IV, Creighton J, Roosa HV, … Sacktor N. A comparison of performance-based measures of function in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Journal of neurovirology. 2011;17(2):159–165. doi: 10.1007/s13365-011-0023-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisslén M, Price RW, Nilsson S. The definition of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders: are we overestimating the real prevalence? BMC infectious diseases. 2011;11:356. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant I, Franklin DR, Deutsch R, Woods SP, Vaida F, Ellis RJ, Letendre SL, Marcotte TD, Atkinson JH, Collier AC, Marra CM, Clifford DB, Gelman BB, McArthur JC, Morgello S, Simpson DM, McCutchan JA, Abramson I, Gamst A, Fennema-Notestine C, Smith DM, Heaton RK, CHARTER Group. Asymptomatic HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment increases risk for symptomatic decline. Neurology. 2014;82:2055–2062. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haziot MEJ, Barbosa SP, Junior, Vidal JE, de Oliveira Francisco Tomaz Meneses, de Oliveira Augusto César Penalvax. Neuroimaging of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Dementia & Neuropsychologia. 2015;9(4) doi: 10.1590/1980-57642015DN94000380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR, Woods SP, Ake C, Vaida F, Ellis RJ, Letendre SL, Marcotte TD, Atkinson JH, Rivera-Mindt M, Vigil OR, Taylor MJ, Collier AC, Marra CM, Gelman BB, McArthur JC, Morgello S, Simpson DM, McCutchan JA, Abramson I, Gamst A, Fennema-Notestine C, Jernigan TL, Wong J, Grant I, CHARTER Group. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology. 2010;75:2087–2096. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Franklin DR, Ellis RJ, McCutchan JA, Letendre SL, Leblanc S, Corkran SH, Duarte NA, Clifford DB, Woods SP, Collier AC, Marra CM, Morgello S, Mindt MR, Taylor MJ, Marcotte TD, Atkinson JH, Wolfson T, Gelman BB, McArthur JC, Simpson DM, Abramson I, Gamst A, Fennema-Notestine C, Jernigan TL, Wong J Grant I, CHARTER Group, HNRC Group. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders before and during the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: differences in rates, nature, and predictors. J Neurovirol. 2011;17:3–16. doi: 10.1007/s13365-010-0006-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Marcotte TD, Mindt MR, Sadek J, Moore DJ, Bentley H, McCutchan JA, Reicks C, Grant I HNRC Group. The impact of HIV-associated neuropsychological impairment on everyday functioning. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004;10:317–331. doi: 10.1017/S1355617704102130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Miller SW, Taylor MJ, Grant I. Revised comprehensive norms for an expanded Halstead-Reitan Battery: Demographically adjusted neuropsychological norms for African American and Caucasian adults. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hinkin CH, Castellon SA, Durvasula RS, Hardy DJ, Lam MN, Mason KI, … Stefaniak M. Medication adherence among HIV+ adults: Effects of cognitive dysfunction and regimen complexity. Neurology. 2002;59:1944–1950. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000038347.48137.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen RS, Cornblath DR, Epstein LG, et al. Nomenclature and research case definitions for neurological manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 (HIV-1) infection. Report of a Working Group of the American Academy of Neurology AIDS Task Force. Neurology. 1991;41:778–785. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.6.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan E, Goodglass H, Weintraub S. Boston Naming Test. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Marcotte TD, Heaton RK, Wolfson T, Taylor MJ, Alhassoon O, Arfaa K, Ellis RJ, Grant I. The impact of HIV-related neuropsychological dysfunction on driving behavior. The HNRC Group. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1999;5(7):579–92. doi: 10.1017/s1355617799577011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer AC, Boscardin WJ, Kwasa JK, Price RW. Is it time to rethink how neuropsychological tests are used to diagnose mild forms of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders? Impact of false-positive rates on prevalence and power. Neuroepidemiology. 2013;41:208–216. doi: 10.1159/000354629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnofsky DA, Burchenal JH. The clinical evaluation of chemo-therapeutic agents in cancer. In: Maclead CM, editor. Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 1949. pp. 191–205. [Google Scholar]

- Kløve H. Grooved pegboard. Indiana: Lafayette Instruments; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNair DM, Lorr M, Droppleman LF. Profile of Mood States. San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Service; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer AC, Boscardin WJ, Kwasa JK, Price RW. Is it time to rethink how neuropsychological tests are used to diagnose mild forms of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders? Impact of false-positive rates on prevalence and power. Neuroepidemiology. 2013;41(3–4):208–216. doi: 10.1159/000354629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan EE, Iudicello JE, Weber E, Duarte NA, Riggs PK, Delano-Wood L, Ellis R, Grant I, Woods SP HNRP Group. Synergistic effects of HIV infection and older age on daily functioning. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61:341–348. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31826bfc53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]