Abstract

Syk is a protein tyrosine kinase that couples B-cell receptor (BCR) activation with downstream signaling pathways, affecting cell survival and proliferation. Moreover, Syk is involved in BCR-independent functions, such as B cell migration and adhesion. In CLL, Syk becomes activated by external signals from the tissue microenvironment, and was targeted in a first clinical trial with R788 (fostamatinib), a relatively non-specific Syk inhibitor. Here, we characterize the activity of two novel, highly selective Syk inhibitors, PRT318 and P505-15, in assays that model CLL interactions with the microenvironment. PRT318 and P505-15 effectively antagonize CLL cell survival after BCR triggering and in nurselike cell (NLC)-co-cultures. Moreover, they inhibit BCR-dependent secretion of the chemokines CCL3 and CCL4 by CLL cells, and leukemia cell migration towards the tissue homing chemokines CXCL12, CXCL13, and beneath stromal cells. PRT318 and P505-15 furthermore inhibit Syk and ERK phosphorylation after BCR triggering. These findings demonstrate that the selective Syk inhibitors PRT318 and P505-15 are highly effective for inhibition of CLL survival and tissue homing circuits, and support the therapeutic development of these agents in patients with CLL, other B cell malignancies, and autoimmune disorders.

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), the most prevalent adult leukemia in Western countries, is characterized by expansion of monoclonal, mature B cells expressing CD5 and CD23(1). Despite major therapeutic advances during the past years, such as introduction of chemo-immunotherapy(2, 3), CLL remains incurable, and the next wave of therapeutic progress will likely be based on our better understanding and targeting of mechanism underlying CLL cell survival and expansion. Proliferation of CLL cells occurs in the tissue compartments (lymphatic tissues, bone marrow), where CLL cells form aggregates of activated, proliferating cell clusters called “proliferation centers” or “pseudofollicles” (4), accounting for a daily turnover of up to 1% of the entire clone(5). Here, CLL cells are in intimate contact with various accessory cells that are not part of the CLL clone, such as T cells (6, 7), actin (αSMA+)-positive mesenchymal stromal cells(8), and monocyte-derived nurselike cells(9, 10). Cellular and molecular interactions with these cells, collectively referred to as the leukemia “microenvironment”, foster CLL cell survival, proliferation, and drug resistance, and hence have become attractive new targets for therapy. Among the diverse molecular pathways of crosstalk between CLL cells and their microenvironment, B cell receptor (BCR) signaling has been recognized as one of the central pathways, based on in vitro(11, 12) and in vivo data(13). Supporting the importance of the BCR in CLL pathogenesis are the notions that prognosis of CLL patients correlates with the amount of somatic mutations in the variable regions of the BCR and that CLL cells express a restricted set of BCR with immunoglobulin (Ig) heavy chain variable (V) gene sequences that are identical or stereotyped in subsets of patients, suggesting that these BCRs bind similar antigens. Moreover, Ig-unmutated and/or ZAP-70 positive patients preferentially respond to BCR stimulation (14) and display gene expression profiles suggesting activation downstream of the BCR(15). Finally, CLL cells isolated from lymph nodes display gene expression profiles indicating BCR activation (13). BCR signaling is a complex process. The BCR is composed of an antigen-specific membrane Ig paired with Ig-α/Ig-β hetero-dimers (CD79α/CD79β).

Engagement of BCRs induces phosphorylation of immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAM) in the cytoplasmatic tails of Ig-α and -β, with subsequent recruitment of SYK to BCR microclusters, followed by phosphorylation of Syk Tyrosine residues. Once activated, Syk phosphorylates several signal intermediates like Btk and BLNK, which in turn activate the downstream signaling molecules NF-kB, Raf, MEK and ERK. Syk signaling is required for B cell development, proliferation, and survival of B cells. Syk-deficient mice show a severe defect of B lymphopoiesis, with a block at the pro-B to pre-B transition. Previous in vitro studies (16, 17) and a clinical trial (18) showed that disrupting BCR signals and microenvironmental interactions with the Syk inhibitor R406 (fostamatinib, also called FosD, or R788 in its oral formulation) is effective in CLL and other B cell malignancies. R406 is an ATP-competitive kinase inhibitor and has limited specificity towards SYK, and also displays activity against other kinases, such as FMS-related tyrosine kinases 3 (FLT3), Lck, and Janus kinase 1 (JAK1) and JAK3 (19). Even through other kinase inhibitors of the same pathways, BTK and PI3K, are being tested in CLL, there are no reported advanced clinical trials, which test the hypothesis of specific SYK inhibition in B cell malignancies. Therefore we evaluated the activity of PRT318 and P505-15 for inhibiting CLL cell activation, survival, and migration.

Methods

CLL cell purification, cell lines, cell viability testing, reagents

After informed consent, peripheral blood samples were obtained from patients fulfilling diagnostic and immunophenotypic criteria for CLL at the Leukemia Department at MD Anderson Cancer Center. Patient consent for samples used in this study was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki on protocols that were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at MD Anderson Cancer Center. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated via density gradient centrifugation over Ficoll-Paque (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) and were used fresh or were placed into fetal bovine serum (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) plus 10% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich) for viable frozen storage in liquid nitrogen. The murine marrow stromal cell (MSC) lines KUSA-H1 and 9-15C were purchased from the Riken cell bank (Tsukuba, Japan) and maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 2.05-mM L-glutamine (HyClone), 10% FBS (SAFC Biosciences), and penicillin-streptomycin (Cellgro). The murine stromal cell line TSt-4 derived from fetal thymus tissue (also from Riken) was maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 2.05-mM L-glutamine, 5% FBS, and penicillin-streptomycin. CLL cell viability was determined by analysis of mitochondrial transmembrane potential using 3,3′ dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide (DiOC6; Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) and by cell membrane permeability to propidium iodide (PI, Sigma) (16).

The Syk inhibitors PRT318 (also called PRT-060318) and P505-15 (also called PRT062607) recently were described (20–22) and were synthesized at Portola Pharmaceuticals (South San Francisco, CA), dissolved in dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) at 10 mM, and stored at −20°C until use. PRT318 and P505-15 are novel small-molecule SYK inhibitors that are more selective and potent (SYK IC50 = 6nM for P505-15, and 3nM for PRT318) (21) than previously described SYK inhibitory compounds, such as R406 (SYK IC50 = 41 nM). Furthermore, the high degree of selectivity of PRT318 in an ambit kinase panel of 318 purified kinases was recently published (Cheng et al, 2011 In Press Blood). P505-15 was similarly screened in the KinaseProfiler panel of 270 independent purified kinase assays, again demonstrating profound specificity for Syk (22).

CLL cell apoptosis in NLC cocultures

NLC co-cultures were established by suspending PBMC from patients with CLL in complete RPMI medium with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine (HyClone) to a concentration of 107 cells/mL (total 2 mL). Cells were incubated for 14 days in 24-well plates (Corning Life Sciences) as previously described (23). To evaluate whether the Syk inhibitors PRT318 and P505-15 could overcome the protective effect of NLC, CLL cells were cultured under standardized conditions on NLC or in suspension, in the presence or absence of PRT318 and P505-15. At the indicated time points, CLL cells were collected and assayed for cell viability as previously described (16).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA)

To evaluate the effect of the Syk inhibitors PRT318 and P505-15 on CCL3 and CCL4 secretion after stimulation of CLL cells with anti-IgM (10 mg/mL) or with NLC, chemokine levels were measured in supernatants of activated CLL cells, as previously described (16, 24). After 24 hours of anti-IgM or NLC co-culture, supernatants were harvested and assayed for CCL3, CCL4, and CXCL13 (only in NLC co-cultures) by quantitative ELISA according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Quantikine, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Chemotaxis assay

To evaluate the impact of PRT318 and P505-15 on CLL cell chemotaxis, we performed chemotaxis assays across polycarbonate Transwell inserts as described (25). Briefly, CLL cells (107/mL) were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 with 10 μg/mL of anti-IgM (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH) in complete RPMI medium with or without 2 μM PRT318 and P505-15. After 1 hour, CLL cells were centrifuged and re-suspended in RPMI 1640 with 0.5% bovine serum albumin to a concentration of 107 cells/mL. 100 μL of cell suspension was added to the top chamber of a Transwell culture insert (Corning, Corning, NY) with a diameter of 6.5 mm and a pore size of 2 μm. Filters then were transferred to wells containing medium with or without 200 ng/mL of CXCL12 (Upstate Biotechnology, Charlottesville, VA) or 1 μg/mL of CXCL13 (R&D Systems, Minnepolis, MN). The chambers were incubated for 3 hours at 37°C in 5% CO2. After this incubation, the cells in the lower chamber were suspended and divided into aliquots for counting with a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) for 20 seconds at 60 μL/min in duplicates. A 1/20 dilution of input cells was counted under the same conditions.

CLL cell migration beneath stromal cells (pseudoemperipolesis)

To determine the effects of the Syk inhibitors PRT318 and P505-15 on spontaneous migration of CLL cells beneath stromal cells, we quantified pseudoemperipolesis, as described. (25) Briefly, the murine stromal cells (9-15C and TSt-4) were seeded the day before the assay onto collagen-coated 12-well plates at a concentration of 1.8 × 105 cells/well in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine. CLL cells at a concentration of 107/mL were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 in complete medium supplemented with or without 2 μM PRT318 or P505-15 for 30 minutes, before addition of 10 μg/mL of anti-IgM. After another 1-hour incubation, CLL cells were then added to the stromal cell layers, and the plates were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 4 hours. Cells that had not migrated into the stromal cell layer were removed by vigorously washing with RPMI medium for 3 times. The complete removal of nonmigrated cells and the integrity of the stromal cell layer containing transmigrated cells were assessed by phase-contrast microscopy and documented photographically. The stromal cell layers containing transmigrated cells were detached by incubation for 1 minute with trypsin/EDTA prewarmed to 37°C (Invitrogen). Cells were then immediately suspended by adding 1 mL of ice-cold RPMI/10% fetal bovine serum, washed, and suspended in 0.4 mL of cold medium for counting by flow cytometry for 20 seconds at 60 μL/min in duplicates. Based on relative differences in size and granularity (forward scatter and side scatter) between cell types, a lymphocyte gate was set to exclude stromal cells from the counts. The number of migrated cells under each condition was expressed as percentage of the control.

Western Blot

Freshly isolated CLL cells were cultured in suspension and stimulated with 10 μg/mL anti-IgM for 10 minutes in the presence or absence of PRT318 or P505-15. Cells then were lysed on ice for 30 minutes in lysis buffer containing 25 mM HEPES, 300 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 20 mM glycerophosohate, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, and protease inhibitor. Cells were centrifuged at 14,000g for 15 minutes at 4°C, and supernatant was stored at −80μC until use. Protein content was determined using the detergent compatible (DC) protein assay kit, according to manufacturer’s instructions (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Aliquots (50 ug) of total cell protein were boiled with Laemmli sample buffer and loaded onto 4% to 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gradient gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (GE Osmonics Labstore, Minnetonka, MN). Membranes were blocked for 1 hour in PBS-Tween containing 5% nonfat dried milk and incubated with primary antibodies either overnight or for 3 hours followed by species-specific horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated secondary antibody (diluted 1:10000) for one hour. The blots were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence according to manufacturer’s instructions (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) and normalized to the actin levels in each extract. Membranes were probed at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: ERK1/2, phospho-ERK (Cell Signaling), and 7beta;-Actin (Sigma-Aldrich). Immunoreactive bands were visualized using peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (GE Healthcare) and enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL).

For Western blots for Syk autophosphorylation 107 SUDHL6 B cells (DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany) were suspended in RPMI media containing 10% FCS and pre-incubated for 30 minutes with or without various concentrations of P505-15. Cells were then stimulated for 30 minutes at 37°C with IgM specific antibody to ligate the BCR. Signaling was terminated by resuspending the cells in RIPA lysis buffer (50mM Tris 7.4, 1% NP40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 150mM NaCl, 0.5mM EDTA), containing fresh protease (Roche) and phosphatase (Sigma) inhibitor tablets, and incubated on ice for 1 hour. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation, and the protein lysates pre-cleared with protein A/G sepharose beads (Peirce, IL). Lysates were incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit anti-Syk antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), and precipitated with protein A/G sepharose beads. Washed beads were denatured and resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE, probed with rabbit anti-Syk, then stripped and re-probed with rabbit anti-Syk Y526/526 (Cell Signaling Technology).

Detection of phospho-proteins by Flow cytometry

Phospho-protein expression in CLL cells after anti-IgM stimulation in the presence or absence of 2μM P505-15 was analysed by flow cytometry, using the following antibodies: anti-pERK Y204-Alexa Fluor 488 (Cell Signaling) and anti-CD19 PECy5 (BD Biosience). In brief, cells were suspended in PBS containing 4% PFA to terminate the 10 minute stimulation reaction. After a 10 minute incubation, cells were washed once in PBS, and then resuspended in 50% methanol in PBS (−80°C) and stored overnight. Cells were then washed and resuspended in PBS containing 1% BSA. For flow cytometry antibodies were added to 0.5×106 cells and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Samples were washed PBS + 1% BSA and resuspend in 350 μl PBS + 1% BSA for assessment on a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences).

Data analysis and statistics

Results are shown as mean plus or minus standard error of mean (SEM) of at least 3 experiments each. As appropriate for the analysis, Student’s paired or unpaired t-tests were used for statistical comparisons. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 4 software for Macintosh (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). A P-value less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Flow cytometry data were analyzed using the FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR).

Results

SYK inhibition induces CLL apoptosis and abrogates BCR-derived survival signals

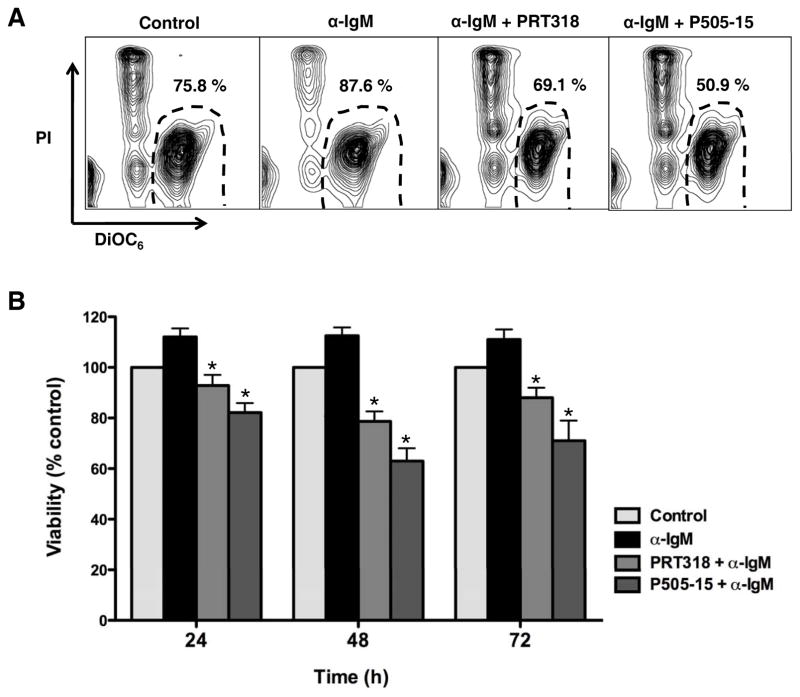

BCR cross-linking with anti-IgM induces BCR activation which can protect CLL cells from undergoing spontaneous apoptosis(16, 26). As shown in a representative case in Figure 1A, the SYK inhibitors PRT318 and P505-15 abrogated the pro-survival effect of anti-IgM and induced CLL cell apoptosis. Figure 1B summarizes the data of 19 different CLL samples, with an increased CLL cell viability of 112% (± 3.5%) after 24 hours of anti-IgM treatment, 112.5% (± 3.9%) after 48 hours, and 111% (± 4%) after 72 hours of anti-IgM stimulation, when compared to respective control CLL cells in medium alone (100%). Treatment with the SYK inhibitor PRT318 decreased the mean (± SEM) CLL cell viability to 78.6 ± 3.9%, and P505-15 (2 mM/mL) decreased CLL cell viability to 62.9 ± 5.1% after 48 hours. Treatment with lower concentrations of PRT318 and P505-15 also reduced the viability of CLL cells as shown in the supplement Figure S1.

Figure 1. SYK inhibition abrogates BCR-derived survival signals and induces CLL cell apoptosis.

(A) Displayed are contour plots that depict CLL cell viability after 48 hours in medium (control), or medium containing 10 μg/mL of anti-IgM in the presence or absence of PRT318 or P505-15, as determined by staining with DiCO6 and PI. The viable cell population is characterized by bright DiCO6 staining and PI exclusion, and is gated in the lower right corner of each of the contour plots. The percentage of viable cells is displayed above each of these gates. (B) This bar diagram represents the mean relative viabilities of CLL cells cultured in medium (control), or medium supplemented with anti-IgM in the presence or absence of PRT318 or P505-15. Viabilities in treated samples were normalized to the viabilities of control samples at the respective time point (100%) to account for differences in spontaneous apoptosis in samples from different patients. The bars represent the mean (± SEM) viabilities from 19 different patient samples, assessed after 24, 48 and 72 hours. Syk inhibition significantly decreased CLL cell viability, with P< .05, as indicated by the asterisks.

SYK inhibitors antagonizes NLC-mediated CLL cell survival

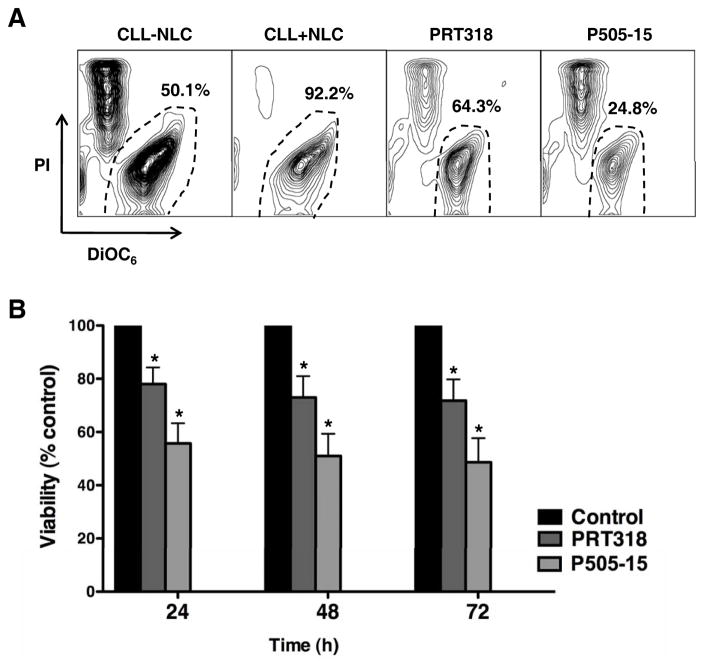

NLC co-cultures activate CLL cells via multiple mechanisms, protect CLL cells from apoptosis, and represent an in vitro system to model the lymphatic tissue microenvironment in CLL. PRT318 and P505-15 were therefore tested in this relevant model system. Figure 2A displays CLL cell viabilities in a representative case, co-cultured with NLC in the presence and absence of PRT318 or P505-15. CLL cell viability in co-cultures with NLC was significantly reduced by the Syk inhibitors; viability in the presence of 2 mM/mL PRT318 was reduced to 73% (± 8%) and to 51% (± 8.3%) by 2 μM/mL P505-15 after 48 hours (mean ± SEM, p < 0.05, n=7, Figure 2B).

Figure 2. SYK inhibitors PRT318 and P505-15 induce CLL cell apoptosis in CLL-NLC co-cultures.

(A) CLL cells were co-cultured with NLC in medium (control) or medium containing PRT318 or P505-15. Presented are contour plots that depict CLL cell viability after 48 hours of incubation, followed by staining with DiOC6 and PI. The viable cell populations are gated in the lower right corner of each of the contour plots, and the percentage of viable cells is displayed above each of these gates. (B) The bar diagram represents the mean relative viabilities of CLL cells co-cultured with NLC (control) compared with CLL cells co-cultured with NLC and PRT318 or P505-15. Viabilities of treated samples were normalized to the viabilities of control samples at the respective time points (100%). Displayed are the means (±SEM) CLL cell viabilities from 7 different CLL samples, assessed after 24, 48 and 72 hours. CLL cell survival in the presence of NLC was significantly inhibited by PRT318 and P505-15, with P<.05, as indicated by the asterisks.

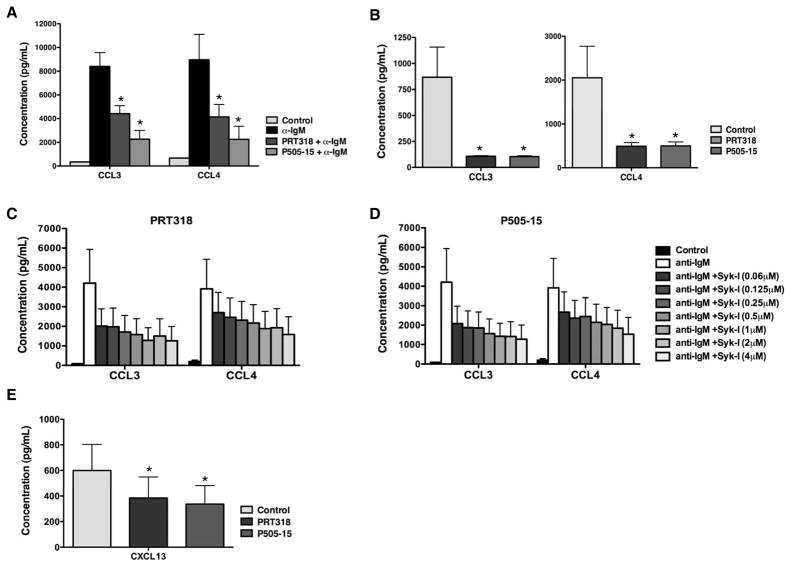

PRT318 and P505-15 inhibit anti-IgM- and NLC-induced secretion of the chemokines CCL3, CCL4, and CXCL13

Anti-IgM- and NLC-activated CLL cells secrete the chemokines CCL3 and CCL4, which appears to correlate with the signaling capacity of the BCR(24, 27). We measured the concentration of CCL3 and CCL4 in supernatant from CLL cells cultured in medium, or medium supplemented with anti-IgM in the presence or absence of PRT318 or P505-15 after 24 hours. As displayed in Figure 3A, PRT318 and P505-15 inhibited the increased secretion of CCL3 and CCL4 after anti-IgM stimulation. The mean (± SEM) CCL3 and CCL4 concentrations in supernatants of CLL cells after anti-IgM stimulation were 8400 ±1166 pg/mL of CCL3 and 8959 ±2147 pg/mL of CCL4. Treatment of CLL cells with PRT318 significantly decreased anti-IgM-induced CCL3 and CCL4 levels to 4425 ± 668 pg/mL (CCL3, n=7, p < 0.05) and 4144 ± 1053 pg/mL (CCL4, n=7, p < 0.05). P505-15 also significantly decreased chemokine levels to 2263 ± 744 pg/mL (CCL3, n=7) and 2250 ±1093 pg/mL (CCL4, n=7). Treatment with lower concentrations of PRT318 and P505-15 also reduced the secretion of CCL3 and CCL4 as shown in figure 3C–D. As reported earlier, the secretion of CCL3 and CCL4 is also markedly increased in NLC co-cultures(24) and in activated CLL cells isolated from lymph nodes(13). Figure 3B depicts significant levels of inhibition of NCL-induced secretion of CCL3 and CCL4 in CLL-NLC co-cultures in the presence of PRT318 and P505-15. The chemokine CXCL13 is also released in CLL-NLC co-cultures to foster cognate interactions between these two cell types. As shown in Figure 3E, CXCL13 was decreased from 599 ±204 pg/mL in control wells to 384 ±164 pg/mL in the presence of PRT318, and to 337 ±144 pg/mL in the presence of P505-15 (mean ± SEM, p=0.05, n=5,).

Figure 3. PRT318 and P505-15 inhibit secretion of the chemokines CCL3, CCL4, and CXCL13, after BCR stimulation and in co-cultures with NLC.

(A) The bar diagram displays mean concentrations of CLL3 and CCL4 in supernatants of CLL cells cultured in medium (control), or medium supplemented with 10 μg/mL anti-IgM in the presence or absence of PRT318 or P505-15. Displayed are the mean (±SEM) chemokine concentrations from 6 different CLL samples assessed after 24 hours. Anti-IgM-induced CCL3 and CCL4 secretion by CLL cells was significantly inhibited by PRT318 and P505-15 (2 μM), with P<.05, as indicated by the asterisks. (B) The bars display the mean CCL3 and CCL4 chemokine levels in supernatants of CLL cells co-cultured with NLC in the presence or absence of 2 μM PRT318 or P505-15. Displayed are the means (±SEM) chemokine concentrations from 7 different patient samples, assessed after 24 hours. CCL3 and CCL4 secretion was significantly inhibited by 2 μM PRT318 and P505-15, with P<.05, as indicated by the asterisks. Lower concentrations of the specific Syk inhibitors PRT318 (C) and P505-15 (D), which are indicated on the right hand side and depicted by different shades of gray, also reduced CCL3 and CCL4 concentrations after BCR stimulation (n=4). (E) This bar diagram represents mean (±SEM) CXCL13 concentrations in supernatants from CLL cells co-cultured with NLC (n=5), assessed after 24 hours. CXCL13 concentrations were significantly reduced by PRT318 and P505-15, with P<.05, as indicated by the asterisks.

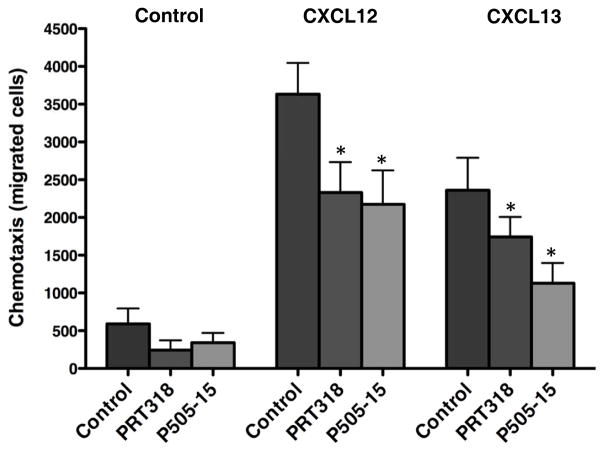

PRT318 and P505-15 inhibit chemotaxis of CLL cells

CLL cells migrate toward the chemokines CXCL12 and CXCL13 after activation of the respective chemokine receptors (CXCR4, CXCR5). SYK is known to be involved in migration of normal and malignant B cells, such as CLL cells(16, 17), via phosphorylation of the F-actin interacting protein SWAP-70(28). As shown in Figure 4, CLL cell chemotaxis towards CXCL12 was significantly decreased from 3632 ± 414 to 2331 ± 402 by RPT318, and to 2174 ± 450 by P505-15 (mean ± SEM number of migrated cells, p=0.05, n=6, while the mean (± SEM) number of cells migrating towards CXCL13 decreased from 2361 ± 429 to 1742 ± 266 by PRT318 and to 1131 ±266 by P505-15 (p=0.05, n=6).

Figure 4. PRT318 and P505-15 inhibit CLL cell chemotaxis towards the chemokines CXCL12 and CXCL13.

CLL cells were pre-incubated in medium (control), or medium containing PRT318 and P505-15, and then allowed to migrate towards 200 ng/mL of CXCL12, or 1 μg/mL of CXCL13, or medium alone. Displayed are bar diagrams that represent the mean (± SEM) numbers of migrated CLL cells from 6 different patients. PRT318 and P505-15 significantly decreased CLL cell chemotaxis towards CXCL12 and CXCL13, with P<.05, as indicated by the asterisks.

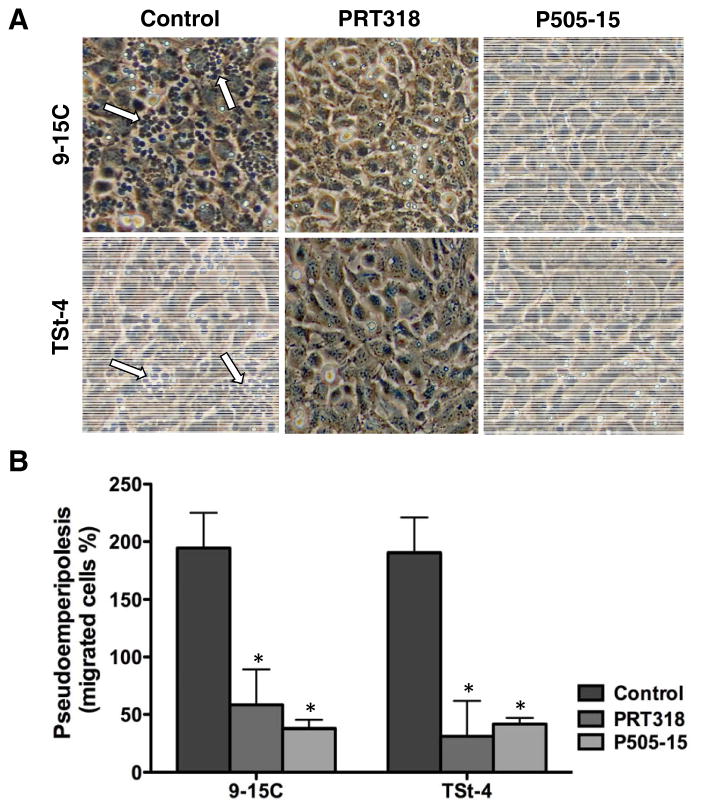

PRT318 and P505-15 antagonize CLL cell migration beneath marrow stroma cells (pseudoemperipolesis)

CLL cell migration beneath stroma cells represents a relevant assay for modeling CLL tissue homing. Given the mobilizing effect of SYK inhibition in CLL in a first clinical trial with fostamatinib(18), we analyzed the effects of PRT318 and P505-15 on CLL cell pseudoemperipolesis. The phase-contrast photomicrographs in Figure 5A depict a significant reduction in CLL cell migration beneath 9-15C and TSt-4 stromal cells after pre-treatment with PRT318 and P505-15 (2μM/mL), when compared to controls. As shown in Figure 5B, CLL cells from 14 patients show significantly reduced pseudoemperipolesis, the number of migrated cells decreased from 18553 ± 4683 to 3383 ± 709 after pre-treatment with 2 μM PRT-318 (mean ± SEM number of migrated cells, p=0.05, n=14) and to 3171 ± 1615 after pre-treatment with 2 μM P505-15 (p=0.05, n=14) using 9-15C stromal cells, and from 10900 ± 4260 to 2280 ± 604 (p=0.05, n=14) and to 2962 ± 1192 (p=0.05, n=14) using TSt-4 stromal cells.

Figure 5. PRT318 and P505-15 thwart CLL cell migration beneath stromal cells (pseudoemperipolesis).

(A) Displayed are representative phase-contrast photomicrographs of CLL cell after migration beneath TSt-4 or 9-15C stromal cells. Before addition to the stromal cells, CLL cells were incubated in medium with or without (control) PRT318 and P505-15. The dark appearance of CLL cells that have migrated into the same focal plane as the stromal cells is characteristic for pseudoemperipolesis, and is highlighted by white arrows in the left hand boxes. The reduced pseudoemperipolesis of CLL cells pre-treated with PRT318 and P505-15 is apparent. (B) The bar diagram represents the mean (±SEM) pseudoemperipolesis of CLL cells from 14 different in the presence or absence of PRT318 and P505-15. The migration beneath both, TSt-4 or 9-15C stromal cells was significantly inhibited by PRT318 and P505-15, with P<.05, as indicated by the asterisks.

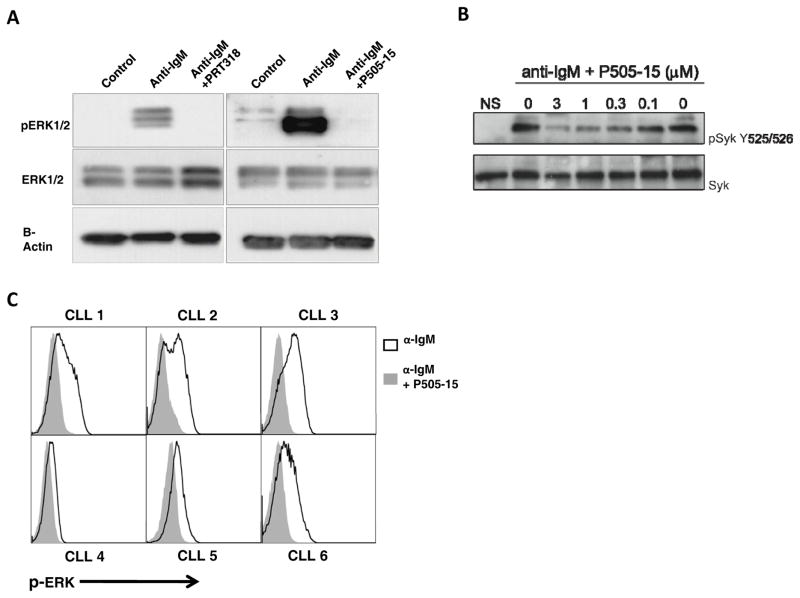

PRT318 and P505-15 block BCR-, CXCR4-, and CXCR5-signaling in CLL cells

As depicted in Fig. 6A, PRT318 and P505-15 both inhibited ERK phosphorylation in response to anti-IgM stimulation. Furthermore, P505-15 inhibited Syk phosphorylation in a dose-dependent fashion, as shown in Fig. 6B in SUDHL6 B cells. We also quantified P-ERK by flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 6C, treatment with P505-15 effectively blocks ERK phosphorylation after anti-IgM stimulation.

Figure 6. PRT318 and P505-15 inhibit BCR-induced ERK and Syk phosphorylation.

(A) Displayed are immunoblots from CLL cells pre-incubated in medium (control), or medium containing 2 μM of PRT318 and P505-15 before activation with anti-IgM for BCR triggering. Syk inhibition with both, PRT318 and P505-15, reduced ERK1/2 phosphorylation after BCR stimulation. For normalization of protein loading, blots were stripped and re-probed with antibodies for total ERK1/2 and actin. (B) SUDHL6 B cells were pre-incubation with different concentrations of P505-15, which are displayed on the horizontal axis, and then activated with anti-IgM. Then cells were lysed, Syk immunoprecipitated, and Western blots performed for Syk (bottom row) and pSyk Y525.526 (top row). P505-15 inhibited Syk activation in a dose-dependent fashion. (C) Inhibition of ERK activation after BCR triggering by PRT318 and P505-15 was also assessed by flow cytometry in CD19+ gated CLL cells from 6 different patients. Overlay histograms depict relative fluorescence intensities of CLL cells stained with fluorescence-labeled anti-pERK mAbs. The black line histograms depict staining of anti-IgM treated CLL cells in the absence of Syk inhibitor, whereas the solid grey histograms depict pERK staining of the CLL cells treated with anti-IgM in the presence of P505-15. As seen in each of the histograms, P505-15 substantially inhibited ERK phosphorylation.

Discussion

Robust preclinical(16, 29, 30) and first clinical evidence(18, 31, 32) supports that targeting BCR signaling is one of the most promising novel therapeutic approaches for treatment of patients with CLL, other B cell malignancies, and autoimmune diseases. Small molecule inhibitors of BCR-associated kinases Syk(18), Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (Btk) (31), and PI3 kinase delta(33, 34) recently entered the clinical stage and show promising clinical activity in patients with B cell lymphomas and leukemias, especially in patients with CLL. Constitutive and inducible activation of Syk in CLL(16, 35) and B cell lymphomas(29, 36) makes this kinase particularly well suited for therapeutic intervention. R406, the first-in-man Syk inhibitor, was tested in a Phase 1/2 study, in which sixty-eight patients with recurrent B cell lymphomas were enrolled. Among those were 11 CLL patients, who had the highest response rate (55%). Here, we tested the hypothesis that direct and specific Syk inhibition with the two Syk inhibitors PRT318 and P505-15 has the ability to inhibit CLL cell activation, migration, and survival. PRT318 and P505-15 share a structural template and are both low nanomolar potency inhibitors of purified Syk. Our findings demonstrate that both, PRT318 and P505-15, are highly effective for inhibition of CLL cell responses to stimulation via the BCR, resulting in reduced CLL cell viability, chemokine secretion, and signaling responses. The fact that PRT318 and P505-15 not only abrogated increased CLL cell viability after anti-IgM stimulation, but furthermore decreased CLL cell viability to levels lower than in untreated controls (Fig. 1, 2) is consistent with the previous notion of constitutively active Syk in CLL(16, 35, 37, 38), which supports the maintenance of basal cell viability in CLL(37, 38) and other B cell mailignancies(36). The effects of PRT318 and P505-15 on CLL cell viability after anti-IgM and in NLC co-cultures are not substantially different from our experience with R406(16), indicating that these are on-target, Syk-specific effects and suggesting that off-target effects of the relatively nonspecific inhibitor R406 do not have a major impact to CLL cell viability in our models. The data by Baudot et al., using pharmacological inhibition of constitutive Syk activity and silencing by siRNA, which caused a dramatic decrease in CLL viability(38), further support this concept.

One of the most remarkable effects of R406 and other inhibitors of BCR-associated kinases is their ability to cause rapid shrinkage of lymph nodes, which is typically accompanied by a substantial, transient lymphocytosis(18, 26, 31). These clinical findings indicate that these kinase inhibitors cause a “mobilization” or “compartment shift” of CLL cells from the tissues into the peripheral blood, where CLL cells then are deprived from tissue-derived survival factors, which, along with Syk-inhibition, causes CLL cell death and over time leads to remissions. Inhibition of chemokine receptor function in CLL cells by Syk inhibition(16, 17, 28) appears to be the central mechanism underlying this finding. Our finding that PRT318 and P505-15 effectively inhibit chemotaxis of CLL cells towards CXCL12 and CXCL13 (Fig. 4) confirm earlier findings with R406(16, 17) and again indicate that these effects are Syk-specific. The importance of Syk for B cell migration is further substantiated by recent findings demonstrating that SWAP-70, an F-actin-binding, Rho GTPase-interacting protein is activated by Syk(28). SWAP-70 is expressed in activated B cells, and necessary for normal B-cell migration in vitro and in vivo(39).

The effects of PRT318 and P505-15 on chemokine secretion (CCL3, CCL4) by CLL cells after stimulation with anti-IgM and NLC points towards another important regulatory axis in the CLL microenvironment. Normally, these chemokines are selectively expressed and secreted by normal follicular B cells in response to BCR activation in order to attract T helper cells for cognate B-T cell interactions(40). In CLL, a similar mechanism appears to operate(24), which presumably allows for T cell attraction to BCR-activated CLL cells in proliferation centers, where CLL cells are in intimate contact with T cells(6, 7). The inhibitory effects of PRT318 and P505-15 on CCL3 and CCL4 secretion is consistent with CCL3 and CCL4 being key BCR response genes(13, 24). CCL3 and CCL4 also are emerging as useful markers for disease monitoring, given that CCL3 and CCL4 levels can easily be measured(24), are prognostic(27), and can be useful for response assessment in CLL(41), particularly in patients undergoing therapy with agents that target BCR signaling, as demonstrated for the PI3 kinase delta inhibitor CAL-101(26).

In summary, our study defines the activity of PRT318 and P505-15, two novel, highly specific Syk inhibitors, on CLL cell activation, survival, and migration. The robust inhibitory actions of these inhibitors in our model systems provide the basis for the clinical development of these agents in CLL and other B cell malignancies, and a roadmap for design of correlative studies on future clinical trials with Syk inhibitors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by CLL Global Research Foundation grants (to W.W., and J.A.B.), and a Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) grant (to J.A.B.).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

J.H. performed the experiments, analyzed the data, designed the figures, and wrote the paper with J.A.B.; G.P.C., U.S., and A.P. performed immunoblots, synthesized and biologically characterized the compounds, helped with the experimental design, and reviewed the manuscript; M.S. assisted with the experiments and reviewed the manuscript; A.F., F.R., W.G.W, M.J.K. S.O.B. provided samples, helped with data interpretation and reviewed the manuscript; and J.A.B. designed the research, supervised the study, analyzed the data, and revised the paper.

Conflict of Interest

J.H., M.S., A.F., F.R., W.G.W, M.J.K., S.O.B., and J.A.B have no conflicts of interest to disclosure related to this study. G.P.C., U.S., and A.P. are employees and shareholders of Portola Pharmaceuticals.

Supplementary information is available at Leukemia’s website

References

- 1.Chiorazzi N, Rai KR, Ferrarini M. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia. The New England journal of medicine. 2005 Feb 24;352(8):804–815. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keating MJ, O’Brien S, Albitar M, Lerner S, Plunkett W, Giles F, et al. Early results of a chemoimmunotherapy regimen of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab as initial therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Jun 20;23(18):4079–4088. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hallek M, Fischer K, Fingerle-Rowson G, Fink AM, Busch R, Mayer J, et al. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010 Oct 2;376(9747):1164–1174. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61381-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stein H, Bonk A, Tolksdorf G, Lennert K, Rodt H, Gerdes J. Immunohistologic analysis of the organization of normal lymphoid tissue and non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. J Histochem Cytochem. 1980 Aug;28(8):746–760. doi: 10.1177/28.8.7003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Messmer BT, Messmer D, Allen SL, Kolitz JE, Kudalkar P, Cesar D, et al. In vivo measurements document the dynamic cellular kinetics of chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2005 Mar;115(3):755–764. doi: 10.1172/JCI23409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghia P, Strola G, Granziero L, Geuna M, Guida G, Sallusto F, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells are endowed with the capacity to attract CD4+, CD40L+ T cells by producing CCL22. European journal of immunology. 2002 May;32(5):1403–1413. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200205)32:5<1403::AID-IMMU1403>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patten PE, Buggins AG, Richards J, Wotherspoon A, Salisbury J, Mufti GJ, et al. CD38 expression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia is regulated by the tumor microenvironment. Blood. 2008 May 15;111(10):5173–5181. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-108605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruan J, Hyjek E, Kermani P, Christos PJ, Hooper AT, Coleman M, et al. Magnitude of stromal hemangiogenesis correlates with histologic subtype of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2006 Oct 1;12(19):5622–5631. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burkle A, Niedermeier M, Schmitt-Graff A, Wierda WG, Keating MJ, Burger JA. Overexpression of the CXCR5 chemokine receptor, and its ligand, CXCL13 in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2007 Nov 1;110(9):3316–3325. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-089409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhattacharya N, Diener S, Idler IS, Barth TF, Rauen J, Habermann A, et al. Non-malignant B cells and chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells induce a pro-survival phenotype in CD14+ cells from peripheral blood. Leukemia. 2011 Apr;25(4):722–726. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiorazzi N, Ferrarini M. B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: lessons learned from studies of the B cell antigen receptor. Annual review of immunology. 2003;21:841–894. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stevenson FK, Caligaris-Cappio F. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: revelations from the B-cell receptor. Blood. 2004 Jun 15;103(12):4389–4395. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herishanu Y, Perez-Galan P, Liu D, Biancotto A, Pittaluga S, Vire B, et al. The lymph node microenvironment promotes B-cell receptor signaling, NF-kappaB activation, and tumor proliferation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2011 Jan 13;117(2):563–574. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-284984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen L, Widhopf G, Huynh L, Rassenti L, Rai KR, Weiss A, et al. Expression of ZAP-70 is associated with increased B-cell receptor signaling in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2002 Dec 15;100(13):4609–4614. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenwald A, Alizadeh AA, Widhopf G, Simon R, Davis RE, Yu X, et al. Relation of gene expression phenotype to immunoglobulin mutation genotype in B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2001 Dec 3;194(11):1639–1647. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.11.1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quiroga MP, Balakrishnan K, Kurtova AV, Sivina M, Keating MJ, Wierda WG, et al. B-cell antigen receptor signaling enhances chronic lymphocytic leukemia cell migration and survival: specific targeting with a novel spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitor, R406. Blood. 2009 Jul 30;114(5):1029–1037. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-212837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchner M, Baer C, Prinz G, Dierks C, Burger M, Zenz T, et al. Spleen tyrosine kinase inhibition prevents chemokine- and integrin-mediated stromal protective effects in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2010 Jun 3;115(22):4497–4506. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-233692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedberg JW, Sharman J, Sweetenham J, Johnston PB, Vose JM, Lacasce A, et al. Inhibition of Syk with fostamatinib disodium has significant clinical activity in non-Hodgkin lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2010 Apr 1;115(13):2578–2585. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-236471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braselmann S, Taylor V, Zhao H, Wang S, Sylvain C, Baluom M, et al. R406, an orally available spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitor blocks fc receptor signaling and reduces immune complex-mediated inflammation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006 Dec;319(3):998–1008. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.109058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reilly MP, Sinha U, Andre P, Taylor SM, Pak Y, Deguzman FR, et al. PRT-060318, a novel Syk inhibitor, prevents heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and thrombosis in a transgenic mouse model. Blood. 2011 Feb 17;117(7):2241–2246. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-274969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andre P, Morooka T, Sim D, Abe K, Lowell C, Nanda N, et al. Critical role for Syk in responses to vascular injury. Blood. 2011 Aug 31; doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-360743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coffey G, Deguzman F, Inagaki M, Pak Y, Delaney SM, Ives D, et al. Specific Inhibition of Syk Suppresses Leukocyte Immune Function and Inflammation in Animal Models of Rheumatoid Arthritis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011 Oct 31; doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.188441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burger JA, Tsukada N, Burger M, Zvaifler NJ, Dell’Aquila M, Kipps TJ. Blood-derived nurse-like cells protect chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells from spontaneous apoptosis through stromal cell-derived factor-1. Blood. 2000;96(8):2655–2663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burger JA, Quiroga MP, Hartmann E, Burkle A, Wierda WG, Keating MJ, et al. High-level expression of the T-cell chemokines CCL3 and CCL4 by chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells in nurselike cell cocultures and after BCR stimulation. Blood. 2009 Mar 26;113(13):3050–3058. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-170415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burger JA, Burger M, Kipps TJ. Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia B Cells Express Functional CXCR4 Chemokine Receptors That Mediate Spontaneous Migration Beneath Bone Marrow Stromal Cells. Blood. 1999;94(11):3658–3667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoellenriegel J, Meadows SA, Sivina M, Wierda WG, Kantarjian H, Keating MJ, et al. The phosphoinositide 3’-kinase delta inhibitor, CAL-101, inhibits B-cell receptor signaling and chemokine networks in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2011 Sep 29;118(13):3603–3612. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-352492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sivina M, Hartmann E, Kipps TJ, Rassenti L, Krupnik D, Lerner S, et al. CCL3 (MIP-1alpha) plasma levels and the risk for disease progression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2011 Feb 3;117(5):1662–1669. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-307249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pearce G, Audzevich T, Jessberger R. SYK regulates B-cell migration by phosphorylation of the F-actin interacting protein SWAP-70. Blood. 2011 Feb 3;117(5):1574–1584. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-295659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen L, Monti S, Juszczynski P, Daley J, Chen W, Witzig TE, et al. SYK-dependent tonic B-cell receptor signaling is a rational treatment target in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2008 Feb 15;111(4):2230–2237. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-100115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davis RE, Ngo VN, Lenz G, Tolar P, Young RM, Romesser PB, et al. Chronic active B-cell-receptor signalling in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Nature. 2010 Jan 7;463(7277):88–92. doi: 10.1038/nature08638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burger JA, O’Brien S, Fowler N, Advani R, Sharman JP, Furman RR, et al. The Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor, PCI-32765, Is Well Tolerated and Demonstrates Promising Clinical Activity In Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) and Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma (SLL): An Update on Ongoing Phase 1 Studies. Blood 2010. 2010 Nov 19;116(21):32a. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weinblatt ME, Kavanaugh A, Genovese MC, Musser TK, Grossbard EB, Magilavy DB. An oral spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) inhibitor for rheumatoid arthritis. The New England journal of medicine. 2011 Sep 30;363(14):1303–1312. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Furman RR, Byrd JC, Brown JR, Coutre SE, Benson DM, Jr, Wagner-Johnston ND, et al. CAL-101, An Isoform-Selective Inhibitor of Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase P110{delta}, Demonstrates Clinical Activity and Pharmacodynamic Effects In Patients with Relapsed or Refractory Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Blood 2010. 2010 Nov 19;116(21):31a. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lannutti BJ, Meadows SA, Herman SE, Kashishian A, Steiner B, Johnson AJ, et al. CAL-101, a p110{delta} selective phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase inhibitor for the treatment of B-cell malignancies, inhibits PI3K signaling and cellular viability. Blood. 2011 Jan 13;117(2):591–594. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-275305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buchner M, Fuchs S, Prinz G, Pfeifer D, Bartholome K, Burger M, et al. Spleen tyrosine kinase is overexpressed and represents a potential therapeutic target in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer research. 2009 Jul 1;69(13):5424–5432. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gururajan M, Jennings CD, Bondada S. Cutting edge: constitutive B cell receptor signaling is critical for basal growth of B lymphoma. J Immunol. 2006 May 15;176(10):5715–5719. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.5715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gobessi S, Laurenti L, Longo PG, Carsetti L, Berno V, Sica S, et al. Inhibition of constitutive and BCR-induced Syk activation downregulates Mcl-1 and induces apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. Leukemia. 2009 Apr;23(4):686–697. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baudot AD, Jeandel PY, Mouska X, Maurer U, Tartare-Deckert S, Raynaud SD, et al. The tyrosine kinase Syk regulates the survival of chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells through PKCdelta and proteasome-dependent regulation of Mcl-1 expression. Oncogene. 2009 Sep 17;28(37):3261–3273. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pearce G, Angeli V, Randolph GJ, Junt T, von Andrian U, Schnittler HJ, et al. Signaling protein SWAP-70 is required for efficient B cell homing to lymphoid organs. Nature immunology. 2006 Aug;7(8):827–834. doi: 10.1038/ni1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krzysiek R, Lefevre EA, Zou W, Foussat A, Bernard J, Portier A, et al. Antigen receptor engagement selectively induces macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha (MIP-1 alpha) and MIP-1 beta chemokine production in human B cells. J Immunol. 1999 Apr 15;162(8):4455–4463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Badoux XC, Keating MJ, Wen S, Lee BN, Sivina M, Reuben J, et al. Lenalidomide as initial therapy of elderly patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2011 Sep 29;118(13):3489–3498. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-339077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.