Abstract

Background

The correlation between treatment satisfaction and demographic characteristics, symptoms, or health-related quality of life (HRQL) in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is unknown. The objective of this study was to assess correlates of treatment satisfaction in patients with GERD receiving a proton pump inhibitor, esomeprazole.

Methods

Adult GERD patients (n = 217) completed demography, symptom, HRQL, and treatment satisfaction questionnaires at baseline and/or after treatment with esomeprazole 40 mg once daily for 4 weeks. We used multiple linear regressions with treatment satisfaction as the dependent variable and demographic characteristics, baseline symptoms, baseline HRQL, and change scores in HRQL as independent variables.

Results

Among the demographic variables only Caucasian ethnicity was positively associated with treatment satisfaction. Greater vitality assessed by the Quality of Life in Reflux and Dyspepsia (QOLRAD) and worse heartburn assessed by a four-symptom scale at baseline, were associated with greater treatment satisfaction. The greater the improvement on the QOLRAD vitality (change score), the more likely the patient is to be satisfied with the treatment.

Conclusions

Ethnicity, baseline vitality, baseline heartburn severity, and change in QOLRAD vitality correlate with treatment satisfaction in patients with GERD.

Keywords: Demography, esomeprazole, Feeling Thermometer, GERD, QOLRAD, treatment satisfaction

Background

The inclusion of patients' opinions in the assessment of interventions has gained greater prominence over the last decades. Regulator agencies now call for the inclusion of patient-reported outcomes (PRO) in clinical trials evaluating pharmaceuticals interventions [1-4]. PRO of interest include health-related quality of life (HRQL), symptom assessment, and more recently, treatment satisfaction, in gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Whereas HRQL measures the patient's physical, psychological, and social level of function, treatment satisfaction assesses the patient's attitude towards the treatment, or the extent to which the patient is satisfied or not with the results of the treatment. Thus, treatment satisfaction focuses on the interaction of expectations and preferences for treatments and is defined as the individual's rating of important attributes of the process and outcomes of the treatment experience [5]. Coyne and co-workers [6] have summarized a number of patient important domains that describe satisfaction with treatment including symptom relief, flexibility with dosing, and treatment expectations. Treatment satisfaction is also associated with prescription regimens that involve less invasive dosing regimens [5,7-10], such as daily versus twice daily use [11].

Evaluating treatment satisfaction may assist healthcare providers in understanding the issues that influence adherence with therapeutic interventions. In addition, treatment satisfaction can be a useful PRO when treatments show similar efficacy because differences in satisfaction could lead to patient preferences for one treatment over another and greater adherence with various treatment regimens.

Demographic variables such as age, ethnicity, and gender may influence satisfaction [12]. Older people tend to be more satisfied with medical care than younger people [13-15], and Caucasian people on the whole are more satisfied than non-Caucasians [16]. In contrast, gender does not appear to influence treatment satisfaction [17].

The objectives of this study were to assess correlates of treatment satisfaction, including demographic factors, symptoms, and HRQL, as well as change scores in PRO instruments in patients with moderate to severe GERD receiving a proton pump inhibitor, esomeprazole.

Methods

Participants

No statistical determination of sample size has been done since the study is of exploratory nature. We enrolled 249 patients with GERD in 13 gastroenterology practices and four general practices across Canada between March 2002 and March 2003.

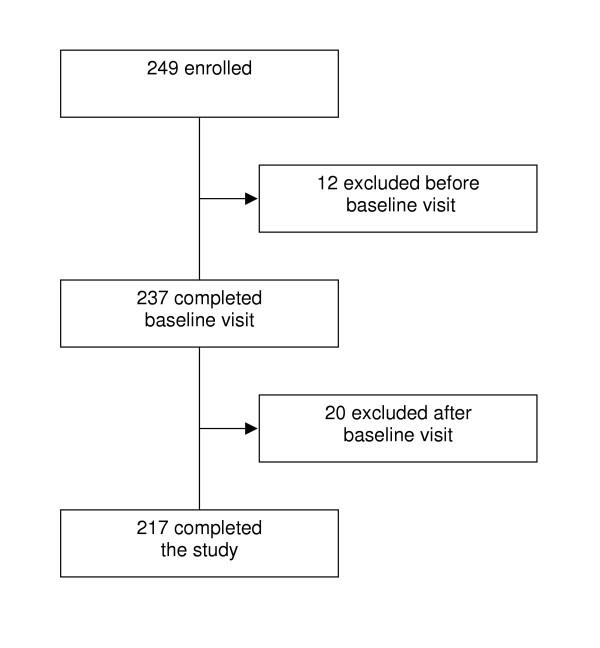

Included patients were 18 years of age or older and had a diagnosis of moderate to severe GERD and presence of symptoms for three months or longer [18]. Prior to inclusion all patients gave written informed consent in accordance with the Helsinki declaration. Of 249 patients, 217 (87%) completed the study. We excluded twelve patients because upon review they did not meet the initial inclusion criteria. Of the 20 patients who withdrew after the baseline visit, 4 withdrew because of adverse events, 2 were unwilling to continue, 4 were lost to follow-up and 10 were excluded because of improper administration or completion of the questionnaires at one visit. Figure 1 shows the flow of patients through the study. The final group of 217 completed patients received four weeks of therapy with esomeprazole 40 mg once daily, in the morning.

Figure 1.

Flow chart

Procedure

Patients completed PRO instruments at the clinic before and approximately 28 days after treatment. The completed PRO instruments included the Quality of Life in Reflux and Dyspepsia (QOLRAD) [19], the Feeling Thermometer (FT) [20], a four symptoms scale, the Standard Gamble (SG) [21], and an upper gastrointestinal (GI) symptom severity scale at baseline and follow-up. Patients completed the Health Utilities Index Mark 2 and 3 (HUI2 and HUI3) [22], and the Medical Outcomes Short-Form 36 (SF-36) [23] at baseline only; and the treatment satisfaction item at follow-up only. We describe these instruments below. In addition, trained research assistants collected information concerning demographic data and clinical data. Each visit lasted approximately 80 minutes.

Treatment satisfaction

Patients rated their satisfaction with treatment on a seven point scale responding to the question: 'How satisfied are you with the study treatment you received?' with the response options: completely satisfied, very satisfied, quite satisfied, no change, dissatisfied, very dissatisfied, and completely dissatisfied.

PRO instruments

QOLRAD

The QOLRAD is a 25-item disease-specific self-administered instrument asking about the impact of heartburn and acid regurgitation on the patient's HRQL during the previous week. The QOLRAD includes questions related to 5 domains; emotional distress, sleep disturbance, problems with food and drink, limitations in physical and social functioning, and lack of vitality. Patients respond to each question on a seven-point scale on which a higher score indicates better HRQL. The psychometric properties concerning validity, reliability, and responsiveness to change are reported elsewhere [19,24]. The minimal important difference (MID) that patients perceive as important is approximately 0.5 on the 1 – 7 scale [25].

FT

The FT is a visual analogue scale that resembles a thermometer. It is divided into 100 segments with a mark to represent each segment. Its anchors are dead (0) and full health (100) [21]. Patients mark their own health state and/or that of hypothetical patient scenarios or clinical marker states. In this study, three patient scenarios represented mild, moderate, and severe GERD. We developed and tested the clincal marker states with patients and clinicians [26]. The MID of the FT is approximately 6 on the 0 to 100 scale [27].

HUI

This is a 15 item questionnaire designed to quantify HRQL [22]. Each item has 4–6 response options. There are 8 attributes in the HUI3 classification system: vision, hearing, speech, ambulation, dexterity, emotion, cognition, and pain. In the HUI2 there are 7 attributes: sensation, mobility, emotion, cognition, self-care, pain, and fertility.

SF-36

The SF-36 contains 36 items that measure 8 dimensions: physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health problems, bodily pain, general health perceptions, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and general mental health. This questionnaire has been extensively tested for validation and reliability [23]. Each domain is scored on a 0 to 100 scale where higher scores indicate better HRQL. Scores on the SF-36 can also be expressed as two summary measures, the physical component score and the mental component score, which provide a measure of the overall effect of physical and mental impairment on HRQL.

Rating of four symptoms

To assess common symptoms in GERD, patients evaluated their heartburn, acid reflux, stomach pain, and belching for the past week using a seven-point scale ranging from no discomfort to very severe discomfort.

SG

The SG involves decision in the face of uncertainty, where in the standard administration the uncertainty involves a risk of death. The SG offers the patients two alternatives from which a choice must be made: Choice A is a hypothetical treatment with two possible outcomes: 1) returning to full health (probability p) for t years, at the end of which they die, or 2) immediate death (probability 1 – p). The alternative (choice B) is a certain outcome that he or she will stay in a health state (their own health state, or a patient scenario) for t years until death. t varies depending on the patient's age. The interviewer used a change board with the ping-pong approach varying the probability p in steps of 0.05 to find the value p where the respondent considered choice A = choice B. This value of p is the utility value for the health state in choice A in the interval from dead (0) to full health (1). The greater a patient's willingness to accept the risk of a worse outcome (e.g. dead) to avoid the health state in choice A, then the lower is the utility of the state in choice A to them.

Rating of upper GI symptom severity

Patients documented the severity of overall upper GI symptom on a seven-graded scale (1 = no symptoms; 7 = severe symptoms) over the past seven days. At baseline, patients who had no, minimal or mild symptoms were not included in this study.

Statistical analyses

We calculated the mean and standard deviation of the basic demographic variables. Our multiple linear regression analysis focused on the outcome variable treatment satisfaction, which we treated as a continuous outcome variable. Evaluation of the data with polynomial regression yielded similar results. Potential correlates were demographic variables and baseline scores, as well as change scores for the PRO instruments described in the previous section. We first modelled these variables univariately as correlates of treatment satisfaction and only those that were significant at p < 0.1 entered into the multiple regression model. After having entered the multiple regression model, only those significant at p < 0.05 remained in the final model.

Results

Table 1 shows the baseline demographic characteristics and frequencies of the included patients. The mean age was 50 years, and approximately 50% of the patients were female. The mean number of months since diagnosis was 86 months. Approximately 70% were full-time or part-time employed, and 88% were Caucasians.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and frequencies at baseline for the study sample (N = 217).

| Frequency | Percentage | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 103 | 47.5 |

| Female | 114 | 52.5 |

| Age | ||

| Mean (SD) | 49.7 (13.7) | |

| Range | 20–82 | |

| Months since diagnosis | ||

| Mean (SD) | 86.3 (99.4) | |

| Range | 1–504 | |

| Smoking history | ||

| Never | 94 | 43.5 |

| Yes | 38 | 17.6 |

| Previous | 84 | 38.9 |

| Living alone | 23 | 10.6 |

| Employed: full-time and part-time | 149 | 68.7 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 191 | 88.0 |

| Other | 26 | 12.0 |

| Severity of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) | ||

| Moderate problem | 112 | 51.6 |

| Moderate severe problem | 74 | 34.1 |

| Severe problem | 27 | 12.5 |

| Very severe problem | 4 | 1.8 |

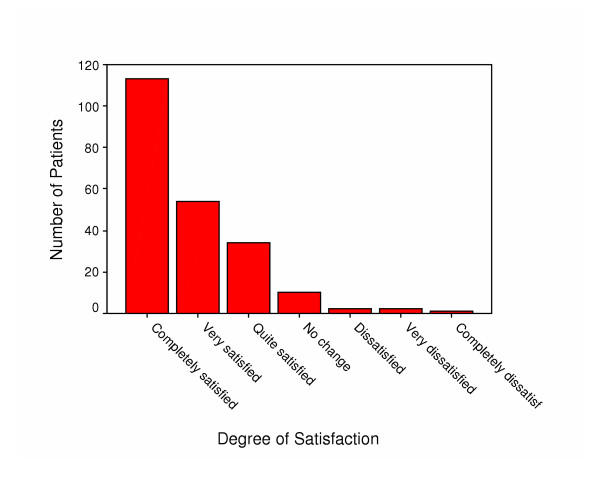

Table 2 depicts the mean baseline scores for the QOLRAD, the four symptoms scale, the FT, the SG, the HUI, and the SF-36. The mean QOLRAD scores at baseline were lowest for the food/drink domain, indicating worse HRQL for this domain, and the mean scores at baseline for the four symptoms show that patients had most problems with heartburn. Furthermore, the mean SF-36 scores at baseline were lowest (worse) for the bodily pain dimension, and highest (best) for the social functioning domain. Figure 2 shows the distribution of the treatment satisfaction scores. Approximately 50% of the patients were completely satisfied, 25% were very satisfied, and approximately 15% were quite satisfied. About 7% reported no change or dissatisfaction of different severity.

Table 2.

Baseline scores for Quality of Life in Reflux and Dyspepsia (QOLRAD), four symptoms, Feeling Thermometer (FT), Standard Gamble (SG), Health Utilities Index Mark 2 and 3 (HUI), and Medical Outcomes Short Form-36 (SF-36).

| Mean | SD | |

| QOLRAD dimensions | ||

| Emotional distress | 4.5 | 1.4 |

| Sleep disturbance | 4.5 | 1.5 |

| Food/drink problem | 3.8 | 1.2 |

| Physical/social functioning | 5.4 | 1.4 |

| Vitality | 4.3 | 1.3 |

| Four symptoms | ||

| Stomach pain | 3.9 | 1.5 |

| Heartburn | 4.5 | 1.2 |

| Belching | 3.6 | 1.6 |

| Acid reflux | 4.1 | 1.6 |

| FT | 0.7 | 0.2 |

| SG | 0.8 | 0.2 |

| HUI2 | 0.8 | 0.2 |

| HUI3 | 0.8 | 0.2 |

| SF-36 | ||

| Physical functioning | 46.6 | 9.0 |

| Role-physcial | 45.5 | 11.4 |

| Bodily pain | 42.8 | 9.4 |

| General health | 46.2 | 9.7 |

| Vitality | 45.9 | 9.8 |

| Social functioning | 47.7 | 10.3 |

| Role-emotional | 46.5 | 12.0 |

| Mental health | 46.9 | 10.4 |

| Physial component | 45.1 | 8.7 |

| Mental component | 47.6 | 11.0 |

Figure 2.

Distribution of treatment satisfaction scores

Table 3 portrays the results from the multiple linear regression analysis. Ethnicity, baseline QOLRAD vitality, baseline heartburn from the four symptoms scale, and QOLRAD vitality change score remained as independent variable when all variables had entered the model. Caucasian patients were more likely to be satisfied with the treatment than patients of other ethnicity. Higher baseline QOLRAD vitality scores, higher levels of heartburn and larger change on the QOLRAD vitality score were associated with greater treatment satisfaction.

Table 3.

Results from the multiple linear regression analysis with treatment satisfaction as outcome variable.

| Correlate variables | Parameter estimate (β) | SE | P-value |

| Ethnicity (Caucasian vs. other) | -0.570 | 0.190 | 0.003 |

| QOLRAD Vitality baseline | -0.628 | 0.068 | <0.001 |

| Four symptoms Heartburn | -0.195 | 0.055 | <0.001 |

| QOLRAD Vitality change | -0.593 | 0.071 | <0.001 |

Note. R2 = 0.34 includes ethnicity, QOLRAD Vitality, heartburn, and QOLRAD Vitality change score

Discussion

The objective of this study was to assess correlates of treatment satisfaction in patients with moderate to severe GERD receiving esomeprazole. We found that Caucasian ethnicity, greater vitality and more severe heartburn at baseline, correlates with treatment satisfaction. Furthermore, the greater the improvement on vitality change score, the more likely the patient is to be satisfied with the treatment.

The strengths of this study include the detailed assessment of a number of demographic characteristics, HRQL and symptoms. However, this study has two important limitations. First, we did not perform a placebo controlled trial limiting our ability to assess satisfaction as a true treatment result versus other reasons for satisfaction. Second, investigators have not conducted a thorough psychometric assessment of the treatment satisfaction instrument we used in this study.

Nevertheless, the present study yields four important results. First, in this sample of GERD patients without prior endoscopic evaluation of their symptoms, Caucasian ethnicity was positively associated with treatment satisfaction. Ethnic origin is perhaps one of the most complex demographic characteristics [12] and it has previously been reported that Caucasian people on the whole are more satisfied than non-Caucasians [16].

Second, higher vitality scores, as assessed by the QOLRAD, were associated with higher treatment satisfaction. A patient's health status prior to receiving treatment may cause the patient to be either more or less satisfied with treatment. Clearly and McNeil [28] reported positive correlations between health status and satisfaction. However, it is unclear if satisfaction was correlated with health status before intervention or with health status after intervention. A possible interpretation of the positive association between QOLRAD vitality and treatment satisfaction in our study might be that patients with a high vitality score at baseline are less distressed by their disease, and therefore tend to be more satisfied. The association in our study between higher vitality scores, as assessed by the QOLRAD, and higher treatment satisfaction is in line with Revicki and co-workers [29] who found that patients reporting greater severity in heartburn symptoms were more likely to report psychological distress and impaired well-being compared with those who reported no or mild symptoms. However, Revicki et al measured HRQL with a generic instrument while we used a disease-specific instrument.

Third, higher scores for heartburn, assessed with the four symptoms scale, were related to higher treatment satisfaction. Thus, in our study population, patients with high discomfort from heartburn at baseline perceived a high satisfaction with treatment.

Fourth, the higher the improvement on the QOLRAD vitality (change score), the more likely the person is to be satisfied with the treatment.

Patients' age is regarded as the most consistent determinant characteristic of satisfaction [13-15]. The results from this study did not reveal that treatment satisfaction was related to age. However, Fitzpatrick [30,31] and Fox and Storms [32] highlight the lack of consistency of the effect of age in satisfaction studies. Since satisfaction studies focused on a variety of concepts, such as satisfaction with medical care, satisfaction with hospital management, satisfaction with health services, and satisfaction with treatment, it might be that the association between age and satisfaction is dependent on the concept assessed. The lack of an association to age reveals also the possible that our study population was too homogenous with regard to age.

Although some studies have reported that patient gender affects satisfaction values [33,34], other studies did not find such association [17,35]. In line with this, in our study population treatment satisfaction was not associated with gender.

The current results may be unique to the study sample since no placebo control group was included in the study and, therefore, we were unable to evaluate whether the factors related to treatment satisfaction are related to real treatment effects or patients' need to please and placebo effects. The efficacy, tolerability and safety of esomeprazole versus other proton pump inhibitors has been shown in other studies [36-40]. In this study, patients had moderate to severe symptoms of GERD and some patients had received proton pump inhibitors prior to this study. The latter indicates that our study population is selected with regard to symptom severity, and mixed with regard to previous medication, which might limit generalizability of the findings. Treatment satisfaction in patients with mild GERD symptoms and with no previous experience of proton pump inhibitors remains unknown.

Investigators often use several PRO instruments, each with many dimensions and single items that are more or less correlated in clinical studies. This can lead to a large number of statistical tests being carried out and an increased risk of statistically significant findings occurring by chance in the absence of adjustment of P-values. In the present report we did not carry out adjustments for multiple comparisons for two main reasons. Firstly, the analysis of correlations was intended to be exploratory rather than confirmatory. Secondly, there is no consensus on how to adjust in analyses of the nature we conducted in this study. A simple adjustment according to Bonferroni would be too conservative, in part because many of the PRO variables are closely correlated.

Different drug therapies may elicit unwanted side-effects, which could compromise the patients' HRQL, and adherence with the treatment. Thus, a challenge in the management of GERD is to achieve as high adherence as possible. In addition, treatment satisfaction can be of use when different drug therapies show similar efficacy since it can lead to a preference for one drug over another and greater adherence.

Our study also supports the need for validated treatment satisfaction instruments because the available instruments vary widely in clinical trials [41] and the majority of studies rely on single items. There is a need for developing and improving psychometric documentation of instruments measuring treatment satisfaction [42].

Conclusions

We examined correlates of treatment satisfaction, including demographic factors, symptoms, and HRQL, as well as change scores in HRQL, in patients with moderate to severe GERD who were not investigated by endoscopy. We observed that Caucasian ethnicity was positively related to treatment satisfaction. Furthermore, higher vitality and more severe heartburn were associated with treatment satisfaction. Finally, the higher the improvement on the QOLRAD vitality (change score), the more likely the patient is to be satisfied with the treatment.

Authors' contributions

Alessio Degl' Innocenti was the project leader for this manuscript, edited the clinical protocol of the study, interpreted the data, and wrote the final manuscript as well as early versions. Gordon H Guyatt and Holger Schünemann were the principal investigators of the study, wrote the clinical protocol and grant application, are responsible for the study protocol, interpreted data and participated in writing the final as well as early versions of this manuscript. Ingela Wiklund contributed to the study protocol, interpreted the data and edited the manuscript. Diane Heels-Ansdell was responsible for the statistical analysis and edited the final manuscript as well as early versions. David Armstrong was co-principal investigator of the study, revised the clinical protocol, assessed patients, interpreted data and edited the final manuscript as well as early versions. Carlo A Fallone and Sander Veldhuyzen van Zanten revised the clinical protocol, assessed patients, interpreted data and edited the final manuscript as well as early versions. Samer El-Dika, Alan N Barkun, and Peggy Austin revised the clinical protocol, interpreted data and edited the final manuscript as well as early versions. Peggy Austin also co-ordinated the study. Lisa Tanser contributed to co-ordination of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. The AstraZeneca global publications group approved the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

Participating investigators and affiliation: Dr. Iain Murray, Quest Clinical Trials, Markham, Ontario; Dr. Daniel Sadowski, Hys Medical Centre, Edmonton, Alberta; Dr. Alan Barkun & Dr. Serge Mayrand, Montreal General Hospital, Montreal, Quebec; Dr. Ford Bursey, St. John General Hospital, St. John's, Newfoundland; Dr. Naoki Chiba, Surrey GI Research/Clinic, Guelph, Ontario; Dr. Lawrence Cohen, Sunnybrook & Women's College, Toronto, Ontario; Dr. Carlo Fallone, Royal Victoria Hospital, Montreal, Quebec; Dr. Francis Joanes, Port Arthur Clinic, Thunder Bay, Ontario; Dr. David Morgan, Hamilton Health Sciences Centre, Hamilton, Ontario; Dr. Marc Bradette, L'Hotel-Dieu de Quebec, Quebec; Dr. David Armstrong, McMaster University Medical Centre, Hamilton, Ontario; Dr. Sander Veldhuyzen van Zanten, Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre, Halifax, Nova Scotia; Dr. Pierre Pare, Hospital St. Sacrement, Quebec, Quebec; Dr. W. Olsheski, Albany Medical Clinic, Toronto, Ontario; Dr. Ivor Teitelbaum, Yorkview Medical Centre, North York, Ontario; Dr. Subodh Kanani, Lakeshore West Medical Professional Centre, Toronto, Ontario; Dr. Paul Braude, Markham Research, Thornhill, Ontario.

Contributor Information

Alessio Degl' Innocenti, Email: alessio.deglinnocenti@astrazeneca.com.

Gordon H Guyatt, Email: guyatt@mcmaster.ca.

Ingela Wiklund, Email: ingela.wiklund@astrazeneca.com.

Diane Heels-Ansdell, Email: ansdell@mcmaster.ca.

David Armstrong, Email: armstro@mcmaster.ca.

Carlo A Fallone, Email: carlo.fallone@mcgill.ca.

Lisa Tanser, Email: lisa.tanser@astrazeneca.com.

Sander Veldhuyzen van Zanten, Email: zanten@dal.ca.

Samer El-Dika, Email: seldika@gmail.com.

Naoki Chiba, Email: chiban@on.aibn.com.

Alan N Barkun, Email: alan.barkun@muhc.mcgill.ca.

Peggy Austin, Email: austinp@mcmaster.ca.

Holger J Schünemann, Email: hjs@buffalo.edu.

References

- Leidy NK, Revicki DA, Geneste B. Recommendation for evaluating the validity of quality of life claims for labeling and promotion. Value Health. 1999;2:113–127. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4733.1999.02210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revicki DA, Osoba D, Fairclough D, Barofsky I, Berzon R, Leidy NK, Rothman M. Recommendations on health-related quality of life research to support labeling and promotional claims in the United States. Qual Life Res. 2000;9:887–900. doi: 10.1023/A:1008996223999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santanello NC, Baker D, Cappelleri JC, Copley-Merriman K, DeMarinis R, Gagnon JP, Hsuan A, Jackson J, Mahmoud R, Morgan M, Osterhaus J, Tilson H, Willke R. Regulatory issues for health-related quality of life – PhRMA Health Outcomes Committee Workshop, 1999. Value Health. 2002;5:14–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4733.2002.51047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassany O, Sagnier P, Marquis P, Fullerton S, Aaronson N. Patient-reported outcomes: The example of health-related quality of life – A European guidance document for the improved integration of health-related quality of life assessment in the drug regulatory process. Drug Inf J. 2002;36:209–238. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver M, Markson PD, Frederick MD, Berger M. Issues in the management of treatment satisfaction. Am J Manag Care. 1997;3:579–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne KS, Wiklund I, Schmier J, Halling K, Degl' Innocenti A, Revicki D. Development and validation of a disease-specific treatment satisfaction questionnaire for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;3:907–915. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlberg A. Patient satisfaction and design of treatment. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1993;11:105–110. doi: 10.3109/02813439308994911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis KS, Bradley C, Knight G, Boulton AJM, Ward JD. Ameasure of treatment satisfaction designed specifically for people with insulin-dependent diabetes. Diabet Med. 1987;5:235–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1988.tb00976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Jr, Davies AR. Behavioral consequences of consumer dissatisfaction with medical care. Eval Program Plann. 1983;6:291–297. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(83)90009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodside AG, Frey LL, Daly RT. Linking service quality, customer satisfaction, and behavioral intention. J Health Care Mark. 1989;9:5–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claxton AJ, Cramer J, Pierce C. A systematic review of the associations between dose regimens and medication compliance. Clin Ther. 1996;23:1296–1310. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(01)80109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitzia J, Wood N. Patient satisfaction: a review of issues and concepts. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:1829–1843. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houts PS, Yasko JM, Kahn SB, Schelzel GW, Marconi KM. Unmet psychological, social, and economic needs of persons with cancer in Pennsylvania. Cancer. 1986;58:2355–2361. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19861115)58:10<2355::aid-cncr2820581033>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard CG, Labrecque MS, Ruckdeschel JC, Blanchard EB. Physician behaviors, patient perceptions, and patient characteristics as predictors of satisfaction of hospitalized adult cancer patients. Cancer. 1990;65:186–192. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900101)65:1<186::aid-cncr2820650136>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahr LK, William SG, El-Hadad A. Patient satisfaction with nursing care in Alexandria, Egypt. Int J Nurs Studies. 1991;28:337–342. doi: 10.1016/0020-7489(91)90060-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe GC, Attkisson CC. The evaluation ranking scale: a new methodology for assessing satisfaction. Eval Program Plann. 1983;6:335–347. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(83)90013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado A, Lopez-Fernandez LA, Luna JD. Influence of the doctor's gender in the satisfaction of the users. Med Care. 1993;31:795–800. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199309000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schünemann HJ, Armstrong D, Fallone CA, Barkun A, Degl' Innocenti A, Heels-Ansdell D, Wiklund I, Tanser L, Chiba N, Austin P, van Zanten S, El-Dika S, Guyatt GH. A randomized multi-center trial to evaluate simple utility elicitation techniques in patients with gastro esophageal reflux disease. Med Care. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wiklund IK, Junghard O, Grace E, Talley NJ, Kamm M, van Zanten SV, Pare P, Chiba N, Leddin DS, Bigard M-A, Colin R, Schoenfeld P. Quality of Life in Reflux and Dyspepsia patients. Psychometric documentation of a new disease-specific questionnaire (QOLRAD) Eur J Surg. 1998. pp. 41–49. [PubMed]

- Schünemann HJ, Guyatt GH, Griffith L, Stubbing D, Goldstein R. A clinical trial to evaluate the responsiveness and validity of two direct health state preference instruments administered with and without hypothetical marker states in chronic respiratory disease. Med Decis Making. 2003;23:140–149. doi: 10.1177/0272989X03251243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett KJ, Torrance GW. Measuring health state preferences and utilities: rating scale, time trade-off, and standard gamble techniques. In: Spilker B, editor. Quality of life and pharmacoeconomics in clinical trials. 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. p. 259. [Google Scholar]

- Torrance GW, Furlong W, Feeny D, Boyle M. Multi-attribute preference functions. Health Utilities Index. Pharmacoeconomics. 1995;7:503–520. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199507060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley NJ, Fullerton S, Junghard O, Wiklund I. Quality of life in patients with endoscopy-negative heartburn: reliability and sensitivity of disease-specific instruments. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1998–2004. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9270(01)02495-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke RJ, Singer J, Guyatt GH. Measurement of health status. Ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Contr Clin Trials. 1989;10:407–415. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(89)90005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schünemann HJ, Stahl E, Austin E, Akl E, Armstrong D, Stubbing D, Guyatt GH. A comparison of presenting hypothetical health states in narrative and table format: results from two randomized studies. Med Decis Making. 2004;24:53–60. doi: 10.1177/0272989X03261566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schünemann HJ, Griffith L, Jaeschke R, Goldstein R, Stubbing D, Guyatt GH. Evaluation of the minimal important difference for the feeling thermometer and St. Georges Respiratory questionnaire in patients with chronic airflow limitation. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:1170–1176. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00115-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary PD, McNeil BJ. Patient satisfaction as an indicator of quality of care. Inquiry. 1988;25:25–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revicki DA, Zodet MW, Joshua-Gotlib S, Levine D, Crawley JA. Health-related quality of life improves with treatment-related GERD symptom resolution after adjusting for baseline severity. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:73. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick R. Satisfaction with health care. In: Fitzpatrick R, editor. The experience of illness. London: Tavistock; 1984. pp. 154–175. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick R. Measurement of patient satisfaction. In: Hopkins D, Costain D, editor. Measuring the outcomes of medical care. London: Royal college of physcians and King's Fund Centre; 1990. pp. 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Fox JG, Storms DM. A different approach to sociodemographic predictors of satisfaction with health care. Soc Sci Med. 1981;15:557–564. doi: 10.1016/0271-7123(81)90079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khayat K, Salter B. Patient satisfaction surveys as a market research tool for general practices. Br J Gen Pract. 1994;44:215–219. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SJ, Calnan M. Convergence and divergence: assessing criteria of consumer satisfaction across general practice, dental and hospital care settings. Soc Sci Med. 1991;33:707–716. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopton JL, Howie JGR, Porter AMD. The need for another look at the patient in general practice satisfaction surveys. Fam Pract. 1993;10:82–87. doi: 10.1093/fampra/10.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahrilas PJ, Falk GW, Johnson DA, Schmitt C, Collins DW, Whipple J, D'Amico D, Hamelin B, Joelsson B. Esomeprazole improves healing and symptom resolution as compared with omeprazole in reflux oesophagitis patients: A randomized controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:1249–1258. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghunath AS, Green JRB, Edwards SJ. A review of the clinical and economic impact of using esomeprazole or lansoprazole for the treatment of erosive esophagitis. Clin Ther. 2003;25:2088–2101. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(03)80207-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards SJ, Lind T, Lundell L. Systematic review of proton pump inhibitors for the acute treatment of reflux oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1729–1736. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter JE, Kahrilas PJ, Johanson J, Maton P, Breiter JR, Hwang C, Marino V, Hamelin B, Levine JG. Efficacy and safety of esomeprazole compared with omeprazole in GERD patients with erosive esophagitis: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:656–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.3600_b.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maton PN, Vakil NB, Levine JG, Hwang C, Skammer W, Lundborg P. Safety and efficacy of long term esomeprazole therapy in patients with healed erosive oesophagitis. Drug Safety. 2001;24:625–635. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200124080-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degl' Innocenti A, Hassing LB, Ingelgård A, Kulich K, Wiklund I. Measuring treatment satisfaction – A review of randomised controlled drug trials. Clin Res Regulatory Affairs. 2004;21:597–606. [Google Scholar]

- Bredar A, Bottomley A. Treatment satisfaction as an outcome measure in cancer clinical treatment trials. Expert Rev Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res. 2002;2:597–606. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2.6.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]