Abstract

Background

The treatment of patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) was transformed by the introduction of intensive care units (ICUs), yet we know little about how contemporary hospitals employ this resource-intensive setting and whether higher use is associated with better outcomes.

Methods

We identified 114,980 adult hospitalizations for AMI from 311 hospitals in the 2009–10 Premier database using codes from the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification. Hospitals were stratified into quartiles by rates of ICU admission for AMI patients. Across quartiles, we examined in-hospital risk-standardized mortality rates and usage rates of critical care therapies for these patients.

Results

Rates of ICU admission for AMI patients varied markedly among hospitals (median 48%, Q1 20% to Q4 71%, range 0%–98%) and there was no association with in-hospital risk-standardized mortality rates (6% all quartiles; p=0.7). However, hospitals admitting more AMI patients to the ICU were more likely to use critical care therapies overall (mechanical ventilation [from Q1 with lowest rate of ICU use to Q4 with highest rate: 13% to 16%], vasopressors/inotropes [17% to 21%], intra-aortic balloon pumps [4% to 7%], and pulmonary artery catheters [4% to 5%]; p for trend <0.05 in all comparisons).

Conclusions

Rates of ICU admission for patients with AMI vary substantially across hospitals and were not associated with differences in mortality, but were associated with greater use of critical care therapies. These findings suggest uncertainty about the appropriate use of this resource-intensive setting and a need to optimize ICU triage for patients who will truly benefit.

Keywords: acute myocardial infarction, intensive care unit, variation

Introduction

Intensive care units (ICUs) transformed the care of patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) at a time when few effective therapies were available. First developed in the 1960s, ICUs introduced continuous electrocardiographic monitoring, resuscitative technologies, and high staffing ratios.1,2 Their initial adoption improved outcomes for these patients in an era when early death and complications were common.3,4 As a result, routine admission to an ICU was quickly and widely accepted as the standard of care for most AMI patients, and subsequently, was strongly endorsed by clinical practice guidelines.5,6

However, given the marked evolution in the clinical care and evidence base for AMI, the value of ICUs for many of these patients in contemporary practice warrants closer scrutiny. Non-critical care wards now possess the capability to provide monitoring and advanced therapies previously limited to ICUs.7,8 Simultaneously, the prognosis of AMI patients has substantially improved as ST-segment elevation myocardial infarctions (STEMIs), complications including shock and heart failure, and short-term mortality have all declined with time,9–14 raising questions about who benefits from ICU care. Finally, ICU care is not only increasingly expensive,15,16 but also facilitates the implementation of resource-intensive strategies that, while essential for some patients, may be discretionary in others.17–19 In part because of uncertainty about the marginal benefit of ICUs for many patients, recent guidelines on AMI no longer contain specific recommendations on ICU use.20,21 Meanwhile, little is known about how hospitals use this resource and whether higher rates of ICU use are associated with better outcomes.

Accordingly, we sought to describe hospital variation in the use of ICUs and associated outcomes for patients with AMI in a large contemporary sample of hospitals in the United States. We hypothesized that large variations exist in rates of ICU use for these patients across hospitals, but that these differences would not be associated with in-hospital mortality. Further, we explored the relationship between hospital rates of ICU use and the utilization of resource-intensive treatment strategies in the overall cohort of AMI patients and the subset of these patients admitted to an ICU.

Methods

Data Source

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using a voluntary, fee-supported database maintained by Premier, Inc. for measuring quality and healthcare utilization. Through 2010, the Premier database contained data on >324 million cumulative hospital discharges, representing approximately 1 out of every 5 hospital discharges nationwide. In addition to information available in standard hospital discharge files, this database contains a date-stamped log of all billed items at the patient level including diagnostic tests, medications, and therapeutic services. Patient data were de-identified in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and a random hospital identifier assigned by Premier was used to identify the hospitals. The Yale University Institutional Review Board reviewed the study protocol and granted a waiver of informed consent for the use of this de-identified database.

Study Population

We included hospitalizations from January 1, 2009 to December 31, 2010 for patients aged 18 years or older with a principal discharge diagnosis of AMI as defined by the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes 410.xx, excluding codes representing subsequent episodes of care (410.x2) and hospitalizations involving transfers. Furthermore, we excluded hospitals with <25 admissions for AMI or no ICU hospitalizations for AMI over the study period to decrease the likelihood of artifactual findings from small sample sizes or the lack of an ICU as an option for hospitalized patients.

Study Variables

ICU Admission Rates

For each hospital, we identified the proportion of hospitalizations for AMI that were directly admitted to an ICU. We defined direct admission to an ICU as having a room and board charge for a medical, coronary, surgical, or general ICU bed during the first hospital day. We also assessed ICU admission patterns among 4 distinct subgroups of hospitalizations for AMI: 1) STEMIs, 2) non-STEMIs (NSTEMIs), 3) patients receiving revascularization therapy, and 4) patients not receiving revascularization therapy. We chose to study variation further across these subgroups, as these patients may differ in acuity of illness and/or monitoring needs. STEMI was identified using ICD-9-CM codes 410.0X-410.8X (excluding 410.7X).9 NSTEMI was identified using ICD-9-CM code 410.7X.22 Revascularization therapy was defined as percutaneous coronary intervention involving angioplasty or stent placement at any time during hospitalization, administration of fibrinolytic therapy, or coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

Mortality

For each hospital, we calculated in-hospital all-cause risk-standardized mortality rates for 1) all patients with AMI and 2) ICU patients with AMI, defined as the subset of all patients with AMI directly admitted to an ICU.

Use of Critical Care Therapy

For each hospital, we calculated the use of critical care therapies among 1) all patients with AMI and 2) ICU patients with AMI. For these outcomes, we hypothesized that hospitals with higher rates of ICU use would be more likely to use critical care therapies in their overall cohort of AMI patients due to greater discretionary use and a gatekeeper effect granting more patients access to such therapies. In contrast, we postulated that such therapies would be less likely to be used in the ICU patient subgroups due to a higher proportion of low-risk patients in the ICU. Critical care therapies were defined as therapies for AMI which, in nearly all cases, would represent interventions used in the ICU, including mechanical ventilation (excluding noninvasive positive pressure ventilation), intravenous vasopressors or inotropes, intra-aortic balloon pumps, and/or pulmonary artery catheters.

Statistical Analysis

Results for categorical variables are reported as percentages. All percentages were rounded to the nearest percent. Percentages <0.5 were rounded to 0. Results for continuous variables are reported with medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). Hospitals were categorized into quartiles based on the proportion of all hospitalizations for AMI admitted to an ICU, with the top quartile (Q4) having the highest rates of admission. Hospital characteristics, mortality, and treatments were assessed across quartiles.

For 1) all patients with AMI and 2) ICU patients with AMI, we calculated in-hospital risk-standardized mortality rates for each hospital using hierarchical logistic regression, employing methods that are used in the outcomes measures publicly reported by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.23,24 We adjusted for patient characteristics including age and comorbidities (Supplemental Table I) classified using the software provided by the Healthcare Costs and Utilization Project of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.25 Variables were selected using a stepwise algorithm. We examined the relationship between ICU admission rates and risk-standardized mortality rates using a scatterplot and compared mortality rates across quartiles. A Kruskal-Wallis test was used to assess statistical significance. We then compared the rate of critical care therapy use across quartiles. A Cochran-Armitage test for trend was used to assess statistical differences in therapy use across quartiles. We considered p-values <0.05 as statistically significant.

Additionally, we performed a sensitivity analysis to examine whether results were dependent on hospital patient volume. Analyses for ICU admission rates, mortality, and use of critical care therapies were repeated in hospitals with ≥258 AMI cases (median volume of our sample) and ≥12 ICU cases per year. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The GLIMMIX procedure was used to estimate the hierarchical logistic models. We generated the figures with R version 2.9.1 (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria).26

This study was funded by grant DF10-301 from the Patrick and Catherine Weldon Donaghue Medical Research Foundation in West Hartford, CT; grant UL1 RR024139-06S1 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences in Bethesda, Maryland; and grant U01 HL105270-05 (Center for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research at Yale University) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in Bethesda, MD. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Donaghue Foundation or of the National Institutes of Health. The authors are solely responsible for the design and conduct of this study, all study analyses, the drafting and editing of the paper, and its final contents.

Results

Hospital Characteristics

We identified 114,136 hospitalizations for AMI in 307 hospitals over the 2-year study period. Of these, 54,527 (48%) involved admission to an ICU on the first hospital day. Among hospitals, the median bed size was 302 (IQR: 186,432), median 2-year volume of hospitalizations for AMI was 258 (IQR: 84,539), and median 2-year volume of ICU hospitalizations for AMI was 112 (IQR: 34,265). Hospitals tended to be located in the South (39%), serve an urban population (83%), and identify as non-teaching (71%; Table I). Across quartiles of ICU admission, hospitals had similar characteristics except that those with the lowest ICU admission rates (Q1) were smaller (42% had ≤200 beds compared with 28%, 22%, and 20% in Q2, Q3, and Q4, respectively) and had a lower 2-year case volume of AMIs (38% had <85 hospitalizations for AMI compared with 25%, 15% and 22% in Q2, Q3, and Q4, respectively). Among patients, the proportion of hospitalizations for STEMI ranged from 32% to 39% from Q1 to Q4, while the proportion of hospitalizations utilizing revascularization therapy ranged from 44% to 51% (Table II).

Table I.

Hospital Cohort Characteristics (N=307)

| All Hospitals (n=307) n(%) | Quartile 1 (Admission Rate ≤34%) (n=77) n(%) | Quartile 2 (Admission Rate 35% – 48%) (n=76) n(%) | Quartile 3 (Admission Rate 49% – 61%) (n=78) n(%) | Quartile 4 (Admission Rate ≥ 62%) (n=76) n(%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of beds | |||||

| 1 – 200 | 85 (28) | 32 (42) | 21 (28) | 17 (22) | 15 (20) |

| 201 – 400 | 130 (42) | 27 (35) | 36 (47) | 31 (40) | 36 (47) |

| 401 – 600 | 64 (21) | 14 (18) | 14 (18) | 19 (24) | 17 (22) |

| >600 | 28 (9) | 4 (5) | 5 (7) | 11 (14) | 8 (11) |

| Volume of hospitalizations for AMI* | |||||

| 25 – 84 | 77 (25) | 29 (38) | 19 (25) | 12 (15) | 17 (22) |

| 85 – 258 | 77 (25) | 17 (22) | 21 (28) | 18 (23) | 21 (28) |

| 259 – 539 | 77 (25) | 15 (19) | 19 (25) | 21 (27) | 22 (29) |

| >539 | 76 (25) | 16 (21) | 17 (22) | 27 (35) | 16 (21) |

| Volume of ICU hospitalizations for AMI* | |||||

| 1 – 34 | 79 (25) | 43 (56) | 18 (24) | 9 (12) | 9 (12) |

| 35 – 112 | 75 (25) | 17 (22) | 23 (30) | 16 (21) | 19 (25) |

| 113 – 265 | 77 (25) | 16 (21) | 22 (29) | 21 (27) | 19 (24) |

| >265 | 76 (25) | 1 (1) | 13 (17) | 32 (41) | 30 (39) |

| Geographic region | |||||

| Midwest | 74 (24) | 19 (25) | 17 (22) | 13 (17) | 25 (33) |

| Northeast | 49 (16) | 17 (22) | 12 (16) | 13 (17) | 7 (9) |

| South | 119 (39) | 27 (35) | 32 (42) | 30 (38) | 30 (40) |

| West | 65 (21) | 14 (18) | 15 (20) | 22 (28) | 14 (18) |

| Population served | |||||

| Urban | 254 (83) | 60 (78) | 62 (82) | 68 (87) | 64 (84) |

| Rural | 53 (17) | 17 (22) | 14 (18) | 10 (13) | 12 (16) |

| Teaching status | |||||

| Non-teaching | 219 (71) | 54 (70) | 55 (72) | 55 (71) | 55 (72) |

| Teaching | 88 (29) | 23 (30) | 21 (28) | 23 (29) | 21 (28) |

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; ICU, intensive care unit

Categories were stratified by quartiles from the overall distribution of volume of hospitalizations for AMI and ICU hospitalizations for AMI. Volume was measured across the 2-year study period.

Table II.

Patient Characteristics (n=114,136).

| All patients (n=114,136) (%) | Quartile 1 (Admission rate ≤34%) (n=24,576) (%) | Quartile 2 (Admission rate 35% – 48%) (n=25,904) (%) | Quartile 3 (Admission rate 49% – 61%) (n=38,121) (%) | Quartile 4 (Admission rate ≥62%) (n=25,535) (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| 18 – 54 | 21 | 18 | 21 | 22 | 24 |

| 55 – 64 | 23 | 20 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 65 – 74 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 22 | 20 |

| 75 – 84 | 20 | 22 | 21 | 20 | 19 |

| ≥85 | 15 | 18 | 16 | 14 | 13 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 60 | 59 | 60 | 61 | 61 |

| Female | 40 | 41 | 40 | 39 | 39 |

| Type of AMI | |||||

| ST-segment elevation | 37 | 32 | 36 | 38 | 39 |

| Non-ST-segment elevation | 63 | 68 | 64 | 62 | 61 |

| Revascularization | |||||

| Yes | 47 | 44 | 47 | 46 | 51 |

| No | 53 | 56 | 53 | 54 | 49 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Cardiogenic shock | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 5 |

| Heart failure | 31 | 33 | 31 | 32 | 27 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 13 | 13 | 12 | 13 | 13 |

| Other neurological disorders | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 20 |

| Diabetes with and without complications | 36 | 36 | 36 | 35 | 35 |

| Hypothyroidism | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 10 |

| Renal failure | 20 | 21 | 20 | 19 | 19 |

| Coagulopathy | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| Obesity | 13 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 13 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 22 | 23 | 21 | 23 | 23 |

| Deficiency anemias | 19 | 19 | 18 | 19 | 19 |

| Depression | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 |

| Hypertension | 70 | 71 | 70 | 70 | 71 |

AMI, acute myocardial infarction

ICU Admission Rates

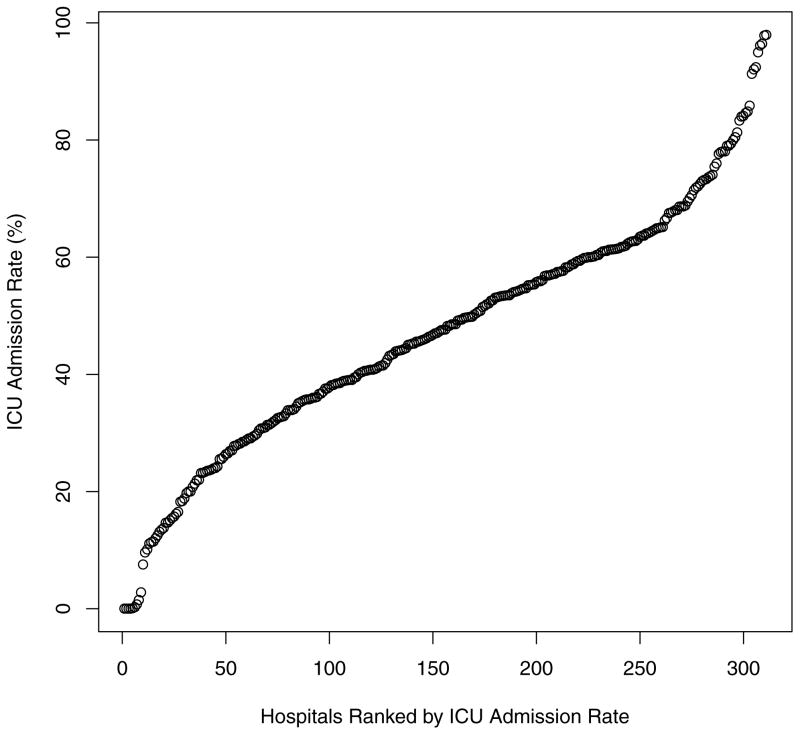

The ICU admission rate for hospitalizations for AMI among hospitals varied markedly with a range from 0% to 98% (median: 48%; IQR: 35–61%; Figure 1). Median ICU admission rates across Q1 through Q4 were 20%, 41%, 55%, and 71%, respectively.

Figure 1.

ICU Admission Rates across Hospitals for All Hospitalizations for AMI (N=307).

Each data point represents a hospital.

Among the subgroups, ICU admission rates also varied widely despite differences in median ICU admission rates. The median ICU admission rate for patients with STEMI was 75% (range 0–100%, Supplemental Figure 1) while the median rate for NSTEMIs was 35% (range 0–96%, Supplemental Figure 2). The median ICU admission rate for patients who received revascularization therapy was 67% (range 0–100%, Supplemental Figure 3) while the median rate for patients who did not receive revascularization therapy was 38% (range 0–97%, Supplemental Figure 4).

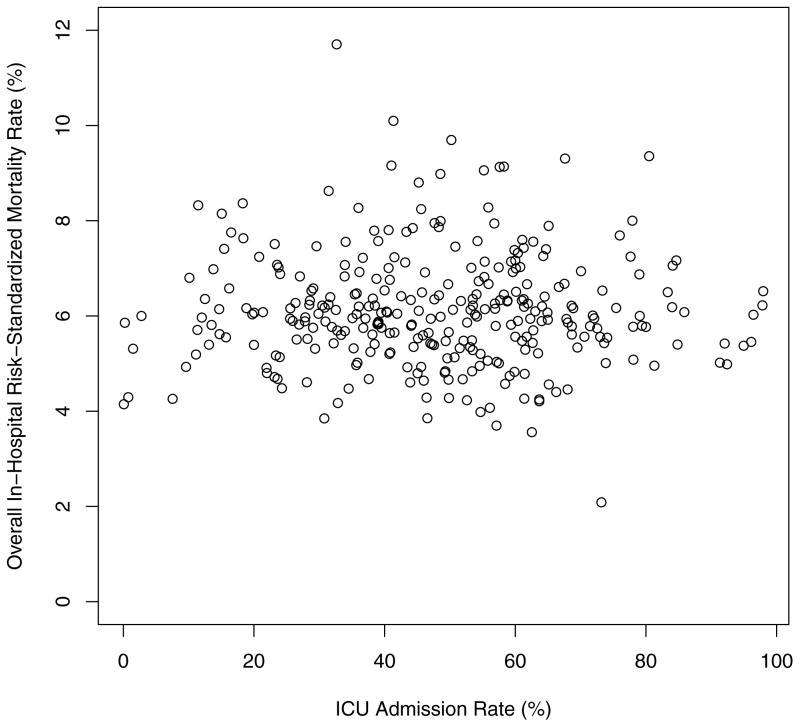

Mortality

There was no relationship between hospital ICU admission rates and in-hospital risk-standardized mortality rates for all patients with AMI (Figure 2). Across quartiles of ICU admission, there was no statistical difference in risk-standardized mortality rates (6.0%, 6.0%, 6.1%, and 5.9% in Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q4 respectively, p=0.7; Table III). For the subgroup of ICU subgroup of ICU patients with AMI, in-hospital risk-standardized mortality rates differed significantly among quartiles. The hospitals with the highest ICU admission rates had the lowest mortality (6.5% in Q4) while lower ICU admission rates were associated with higher mortality in ICU patients (7.1%, 7.9%, and 8.7% in Q3, Q2, and Q1, respectively; p<0.01; Table III). For the subgroup of non-ICU patients with AMI, there was again no statistical difference in risk-standardized mortality rates across quartiles of ICU admission (4.5%, 4.6%, 4.4%, and 4.6% in Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q4 respectively, p=0.9; Table III).

Figure 2.

Overall In-Hospital Risk-Standardized Mortality Rates across Hospital ICU Admission Rates for AMI (N=307).

Each data point represents a hospital.

ICU, intensive care unit; AMI, acute myocardial infarction

Table III.

Risk-Standardized In-Hospital Mortality Rates across Hospitals (N=307 hospitals).

| Patient Group | Quartile 1 (Admission Rate ≤34%; n=77) | Quartile 2 (Admission Rate 35% – 48%; n=76) | Quartile 3 (Admission Rate 49% – 61%; n=78) | Quartile 4 (Admission Rate ≥62%; n=76) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICU patients with AMI | 8.7% | 7.9% | 7.1% | 6.5% | <0.01 |

| Non-ICU patients with AMI | 4.5% | 4.6% | 4.4% | 4.6% | 0.94 |

| All patients with AMI | 6.0% | 6.0% | 6.1% | 5.9% | 0.73 |

AMI, acute myocardial infarction

Use of Critical Care Therapy

All Patients with AMI

The proportion of all patients with AMI utilizing critical care therapies increased across quartiles of increasing hospital ICU admission rates. From Q1 to Q4, there was a significantly increasing trend in the use of mechanical ventilation from 13% to 16%, vasopressors or inotropes from 17% to 21%, intra-aortic balloon pumps from 4% to 7%, pulmonary artery catheters from 4% to %5, and any of the 4 therapies from 21% to 26% (p<0.05 for all comparisons; Table IV).

Table IV.

Critical Care Therapy Utilization across Hospitals for All Patients with AMI (N=114,136).

| Therapy | Usage of therapy (Proportion of hospitalizations utilizing therapy; %)

|

P-value for trend | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile 1 (Admission rate ≤34%) (n=24,576) | Quartile 2 (Admission rate 35% – 48%) (n=25,904) | Quartile 3 (Admission rate 49% – 61%) (n=38,121) | Quartile 4 (Admission rate ≥62%) (n=25,535) | ||

| Mechanical ventilation | 13 | 15 | 15 | 16 | <0.01 |

| Vasopressors and/or inotropes | 17 | 18 | 20 | 21 | <0.01 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump | 4 | 5 | 5 | 7 | <0.01 |

| Pulmonary artery catheter | 4 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 0.04 |

| Any therapy | 21 | 23 | 25 | 26 | <0.01 |

AMI, acute myocardial infarction

ICU Patients with AMI

Among the subgroup of ICU patients with AMI, there was a significantly decreasing trend in the proportion of patients receiving critical care therapies across quartiles of increasing ICU admission rates. From Q1 to Q4, there was a decrease in the use of mechanical ventilation from 28% to 18%, vasopressors or inotropes from 35% to 24%, intra-aortic balloon pumps from 12% to 9%, pulmonary artery catheters from 6% to 5%, and any of the 4 therapies from 43% to 30% (p<0.01 for all comparisons; Table V).

Table V.

Critical Care Therapy Utilization across Hospitals for ICU Patients with AMI (N=54,527).

| Therapy | Usage of therapy (Proportion of hospitalizations utilizing therapy; %)

|

P-value for trend | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile 1 (Admission rate ≤34%) (n=4,860) | Quartile 2 (Admission rate 35% – 48%) (n=10,537) | Quartile 3 (Admission rate 49% – 61%) (n=20,940) | Quartile 4 (Admission rate ≥62%) (n=18,190) | ||

| Mechanical ventilation | 28 | 22 | 19 | 18 | <0.01 |

| Vasopressors and/or inotropes | 35 | 26 | 25 | 24 | <0.01 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump | 12 | 9 | 8 | 9 | <0.01 |

| Pulmonary artery catheter | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | <0.01 |

| Any therapy | 43 | 34 | 31 | 30 | <0.01 |

ICU, intensive care unit; AMI, acute myocardial infarction

Sensitivity Analysis

The sensitivity analysis, after excluding hospitals with <258 AMI cases and <12 ICU admissions for AMI per year, continued to show wide variation in ICU admission rates across hospitals (IQR 37%–61%), no significant difference in risk-standardized in-hospital mortality rates across quartiles (p=0.7), and similar trends in critical care therapy use (increasing trend among all patients with AMI; decreasing trend among ICU patients with AMI; p<0.01 for both).

Discussion

We found that ICU admission rates for AMI varied substantially across hospitals but were not associated with differences in overall mortality after accounting for case mix. Hospitals admitting a greater percentage of AMI patients to the ICU were more likely to perform invasive critical care interventions overall, but their use of these interventions and risk-standardized mortality rates were significantly lower in the ICU subgroup of patients with AMI. Together with the similar mortality rates seen in the overall group of patients with AMI and the non-ICU subgroup of patients with AMI, these results suggest that at the margin, hospitals admitting a larger proportion of patients to the ICU may be admitting a group of patients with weaker indications for critical care therapies.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine hospital-level variation in ICU utilization for AMI and its association with outcomes in such a large sample of hospitals. Although critical care may be a lifesaving intervention for appropriate patients, it may not be providing value for all patients. The decision to use an ICU is important not only because it is resource intensive,15 but also because ICUs potentially pose inherent risks for patients.27–29 Our findings suggest that we may not be optimally utilizing these highly specialized resources.

These findings highlight the decision to use an ICU for AMI patients as a potential target for improvement. As early as 1987, Wagner noted a significant portion of the general ICU population in hospitals were low-risk patients admitted for monitoring, of which only 4.3% received any critical care treatments, and called for a reassessment of contemporary ICU utilization to guide optimization of use.30 More than half of patients directly admitted to the ICU have a 30-day mortality of 2% or less,31 and hospitals demonstrate significant variation in their utilization of ICU care for all patients as well as for patients with specific conditions such as acute decompensated heart failure and diabetic ketoacidosis.31–34 We extend this work to patients with AMI in a contemporary patient population. Compared with previous work on heart failure patients and the overall patient population, AMI patients have a higher median hospital ICU admission rate and wider variation across hospitals (IQR 35–61% for AMI versus 6–16% for heart failure and 4.7–10% or 9–17% for all diagnoses).31–33 Such differences suggest that patients with AMI account for a relatively higher cost and resource burden on the overall healthcare system and high-admitting hospitals in particular, highlighting the need to optimize utilization in this key population.

Our results suggest that variation across hospitals in ICU triage may be more due to hospital factors rather than patient characteristics. For example, we found that patient demographics and comorbidities were comparable across the 4 quartiles of hospitals. Wide variations in rates of ICU admission across hospitalizations were identified in all patient subgroups. This includes STEMI patients, NSTEMI patients, and patients who did and did not undergo revascularization therapy, suggesting that no particular group was responsible for this hospital-level variation. Our findings are consistent with previous literature for other conditions suggesting that patient characteristics explain only a modest proportion of the variation in ICU use.31 The lack of consistency in ICU use likely reflects a large discretionary component that includes consideration of bed availability, patients’ wishes, physician incentives, and differing beliefs about best practices.32,35,36

There are several possible explanations for our findings. Hospitals that admit a large proportion of patients with AMI to the ICU may have lower thresholds for ICU admission, and thereby use intensive care for lower risk patients who are less likely to have adverse outcomes or need critical care therapies. Consistent with this hypothesis, we found a trend that ICU patients with AMI were less likely to receive critical care interventions and had lower mortality at higher-admitting hospitals, while overall and non-ICU mortality rates remained similar. An alternative explanation may be that high-admitting hospitals are improving patient outcomes with ICU admission and low-admitting hospitals may be undertreating patients outside the ICU. However, this seems unlikely given that across quartiles, patient characteristics were similar, and both overall and non-ICU mortality rates for AMI did not differ despite widely varying rates of ICU and critical care therapy use. If low-admitting hospitals were inappropriately triaging patients who would have benefited from ICU care, then non-ICU mortality rates would be significantly higher, which was not the case.

Our results have important implications for health system leaders and policymakers seeking to improve the efficiency of inpatient care. This pattern of care for AMI in high-admitting hospitals—higher overall use of ICUs and critical care therapies across all patients combined with the lower use of critical care therapies per ICU patient—suggests an opportunity where improving triage could enhance resource utilization without undermining outcomes.

Several strategies may provide practical approaches to improve use of the ICU for patients with AMI. At the provider level, a renewed emphasis may need to be placed on the use of appropriate risk stratification for AMI patients at presentation. Well-validated risk prediction models exist to accurately predict in-hospital adverse cardiac outcomes, such as the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) and the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) scores.37,38 Other studies have specifically identified clinical features and risk factors that predict complications and critical care needs.39 Low-risk patients identified with these tools have excellent in-hospital and long-term outcomes and may not routinely require ICU admission. Furthermore, for many patients admitted to ICUs for monitoring and prevention of complications, an intermediate-care strategy such as step-down units or general telemetry units may provide an equally safe yet more cost-effective alternative, a concept that is borne out in limited existing literature and may merit additional consideration.40 Risk prediction models can also effectively guide admission to these units in an effort to optimize utilization and cost through a more gradated system of care.41 Finally, further investigation should focus on better understanding the drivers of these hospital-level variations or phenotypes, the population of AMI patients who most benefit from ICU admission, and the point at which marginal benefit from ICU admission ceases.

Several factors should be considered in interpreting our results. There may be a potential role of closer ICU monitoring to prevent or treat complications, thereby improving patient outcomes. This benefit was not clearly evident in our study, as we did not find any improvement in overall risk-standardized mortality rates among all AMI patients in the hospitals that were the highest admitters to ICUs. However, as our data were based on hospital-level analyses, our findings do not preclude potential benefits of greater monitoring on a patient-level, case-by-case analysis. We performed hospital risk adjustment using age, sex, and comorbidities derived from administrative data. Although clinical data are typically superior to claims data for patient-level risk adjustment, claims-based hospital-level risk adjustment has been shown to produce similar results at the hospital level.23,24 Nevertheless, we were unable to apply a clinical risk score to assess the extent to which ICU use was calibrated to patients’ underlying clinical risk. The ICD-9-CM codes used to define STEMI and NSTEMI have been shown to have only approximately 80% agreement with clinical diagnoses, and therefore may occasionally cause misclassification.9,22 Further, we could not obtain from our data set the total number of ICU beds or beds available at the time of each admission, the type of ICU each patient was admitted to, and could not identify who or which specialties cared for the patient. While we recognize that factors such as bed availability and provider preference may influence triage decisions and outcomes, these influences are part of the variation that we are seeking to describe. Future research may be targeted towards a more granular understanding of how or why such factors engender the variations that we observed. We were also unable to track patients after hospital discharge, so longer-term outcomes could not be evaluated. Finally, our hospital cohort may not be representative of general ICU triage patterns; however, the Premier network covers much of the United States.

In conclusion, we revealed marked variation in ICU admission across hospitals for patients admitted with AMI. We failed to find any relationship between more intensive use of ICUs and better outcomes, even though increased ICU use was associated with greater use of critical care resources. The pattern among those patients admitted to the ICU suggests that hospitals with higher utilization may have a lower threshold for admitting patients. These findings identify an opportunity to improve ICU use through optimizing triage decisions and determining which patients truly derive benefit from the intensive care setting.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was funded by grant DF10-301 from the Patrick and Catherine Weldon Donaghue Medical Research Foundation in West Hartford, CT; grant UL1 RR024139-06S1 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences in Bethesda, Maryland; and grant U01 HL105270-05 (Center for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research at Yale University) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in Bethesda, MD. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Donaghue Foundation or of the National Institutes of Health.

Role of Sponsors: The funding sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr. Krumholz reports that he is the recipient of research agreements with Medtronic and with Johnson & Johnson, through Yale University, to develop methods of clinical trial data sharing and is chair of a cardiac scientific advisory board for United Health. Dr. Masoudi reports having contracts with the Oklahoma Foundation for Medical Quality and the American College of Cardiology Foundation.

References

- 1.Committee on Guidelines of the Society of Critical Care Medicine. Guidelines for organization of critical care units. JAMA. 1972;222:1532. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Day HW. An intensive coronary care area. Dis Chest. 1963;44:423–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.44.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Killip T, Kimball JT. Treatment of myocardial infarction in a coronary care unit. A two year experience with 250 patients. Am J Cardiol. 1967;20:457–64. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(67)90023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katz JN, Shah BR, Volz EM, et al. Evolution of the coronary care unit: clinical characteristics and temporal trends in healthcare delivery and outcomes. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:375–81. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cb0a63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction) developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:e1–e157. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction--executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:671–719. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calvin JE, Habet K, Parrillo JE. Critical care in the United States. Who are we and how did we get here? Crit Care Clin. 1997;13:363–76. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(05)70315-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bodin DA. Telemetry beyond the ICU. Nurs Manage. 2003;34:46–50. doi: 10.1097/00006247-200308000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeh RW, Sidney S, Chandra M, et al. Population trends in the incidence and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2155–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen J, Normand SL, Wang Y, et al. Recent declines in hospitalizations for acute myocardial infarction for Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries: progress and continuing challenges. Circulation. 2010;121:1322–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.862094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen HL, Saczynski JS, Gore JM, et al. Long-term trends in short-term outcomes in acute myocardial infarction. Am J Med. 2011;124:939–46. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldberg RJ, Spencer FA, Gore JM, et al. Thirty-year trends (1975 to 2005) in the magnitude of, management of, and hospital death rates associated with cardiogenic shock in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a population-based perspective. Circulation. 2009;119:1211–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.814947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldberg RJ, Yarzebski J, Spencer FA, et al. Thirty-year trends (1975–2005) in the magnitude, patient characteristics, and hospital outcomes of patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by ventricular fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:1595–601. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang J, Alderman MH, Keenan NL, et al. Acute myocardial infarction hospitalization in the United States, 1979 to 2005. Am J Med. 2010;123:259–66. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chalfin DB, Cohen IL, Lambrinos J. The economics and cost-effectiveness of critical care medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1995;21:952–61. doi: 10.1007/BF01712339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halpern NA, Pastores SM. Critical care medicine in the United States 2000–2005: an analysis of bed numbers, occupancy rates, payer mix, and costs. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:65–71. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b090d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herlitz J, Karlson BW, Karlsson T, et al. A description of the characteristics and outcome of patients hospitalized for acute chest pain in relation to whether they were admitted to the coronary care unit or not in the thrombolytic era. Int J Cardiol. 2002;82:279–87. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(02)00009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Driscoll A. Coronary care units continue to be effective at improving patient outcomes. Aust Crit Care. 2012;25:143–6. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rotstein Z, Mandelzweig L, Lavi B, et al. Does the coronary care unit improve prognosis of patients with acute myocardial infarction? A thrombolytic era study. Eur Heart J. 1999;20:813–8. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1998.1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;127:e362–425. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182742cf6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jneid H, Anderson JL, Wright RS, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA focused update of the guideline for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2007 guideline and replacing the 2011 focused update): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2012;126:875–910. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318256f1e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steinberg BA, French WJ, Peterson E, et al. Is coding for myocardial infarction more accurate now that coding descriptions have been clarified to distinguish ST-elevation myocardial infarction from non-ST elevation myocardial infarction? Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:513–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krumholz HM, Wang Y, Mattera JA, et al. An administrative claims model suitable for profiling hospital performance based on 30-day mortality rates among patients with an acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2006;113:1683–92. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.611186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krumholz HM, Lin Z, Drye EE, et al. An administrative claims measure suitable for profiling hospital performance based on 30-day all-cause readmission rates among patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4:243–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.957498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, et al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ihaka R, Gentleman R. R: A language for data analysis and graphics. J Comp Graph Stat. 1996;5:299–314. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Girard TD, Pandharipande PP, Ely EW. Delirium in the intensive care unit. Crit Care. 2008;12(Suppl 3):S3. doi: 10.1186/cc6149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levy MM, Rapoport J, Lemeshow S, et al. Association between critical care physician management and patient mortality in the intensive care unit. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:801–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-11-200806030-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomas EJ, Lucke JF, Wueste L, et al. Association of telemedicine for remote monitoring of intensive care patients with mortality, complications, and length of stay. JAMA. 2009;302:2671–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wagner DP, Knaus WA, Draper EA. Identification of low-risk monitor admissions to medical-surgical ICUs. Chest. 1987;92:423–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.92.3.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen LM, Render M, Sales A, et al. Intensive care unit admitting patterns in the Veterans Affairs health care system. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1220–6. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seymour CW, Iwashyna TJ, Ehlenbach WJ, et al. Hospital-level variation in the use of intensive care. Health Serv Res. 2012;47:2060–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01402.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Safavi KC, Dharmarajan K, Kim N, et al. Variation exists in rates of admission to intensive care units for heart failure patients across hospitals in the United States. Circulation. 2013;127:923–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.001088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gershengorn HB, Iwashyna TJ, Cooke CR, et al. Variation in use of intensive care for adults with diabetic ketoacidosis. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2009–15. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31824e9eae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Escher M, Perneger TV, Chevrolet JC. National questionnaire survey on what influences doctors’ decisions about admission to intensive care. BMJ. 2004;329:425. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7463.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sprung CL, Geber D, Eidelman LA, et al. Evaluation of triage decisions for intensive care admission. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1073–9. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199906000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Granger CB, Goldberg RJ, Dabbous O, et al. Predictors of hospital mortality in the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2345–53. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.19.2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Antman EM, Cohen M, Bernink PJ, et al. The TIMI risk score for unstable angina/non-ST elevation MI: a method for prognostication and therapeutic decision making. JAMA. 2000;284:835–42. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.7.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goldman L, Cook EF, Johnson PA, et al. Prediction of the need for intensive care in patients who come to the emergency departments with acute chest pain. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1498–504. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199606063342303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fiebach NH, Cook EF, Lee TH, et al. Outcomes in patients with myocardial infarction who are initially admitted to stepdown units: data from the Multicenter Chest Pain Study. Am J Med. 1990;89:15–20. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90091-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zimmerman JE, Wagner DP, Knaus WA, et al. The use of risk predictions to identify candidates for intermediate care units. Implications for intensive care utilization and cost. Chest. 1995;108:490–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.2.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.