Abstract

Importance

The majority of young adults who have an AMI are sexually active before AMI, but little is known about sexual activity or sexual function afterwards.

Objective

Describe patterns of sexual activity and function and identify predictors of loss of sexual activity in the year after AMI.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Data from the prospective, longitudinal Variation in Recovery: Role of Gender on Outcomes of Young AMI Patients (VIRGO) study (2008–12) were assessed at baseline, one month, and one year. Participants (women = 1,889; men = 913) were ages 18–55 at enrollment from United States (n=103) and Spanish (n= 24) hospitals who completed baseline and all follow-up interviews. Characteristics associated with loss of sexual activity were assessed using multinomial logistic regression analyses.

Main Outcome Measure

Loss of sexual activity after AMI.

Results

At all time points, 40% of women and 55% of men were sexually active. Among people who were sexually active at baseline, men were more likely than women to have resumed sexual activity by one month (64% versus 55%, p<0.001) and by one year (94% versus 91%, p=0.01) after AMI. Among people who were sexually active before and after AMI, women were less likely than men to report no sexual function problems in the year after (40% vs. 55%, p<0.01). Additionally, more women than men (42% vs. 30%, p<0.01) with no baseline sexual problems developed one or more incident problems in the year after AMI. At one year, the most prevalent sexual problems were lack of interest (40%) and trouble lubricating (22%) among women; and erectile difficulties (22%) and lack of interest (19%) among men. Those who had not communicated with a physician about sex in the first month after AMI were more likely to delay resuming sex (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 1.51, 95% CI 1.11–2.05; p=0.008). Higher stress levels (AOR 1.36, 95% CI 1.01–1.83) and having diabetes (AOR 1.90, 95% CI 1.15–3.13) were significant predictors of loss of sexual activity in the year after AMI.

Conclusions and Relevance

Impaired sexual activity and incident sexual function problems were prevalent and more common among young women than men in the year after AMI. Attention to modifiable risk factors and physician counseling may improve outcomes.

Trial registration

INTRODUCTION

Nearly 20% of acute myocardial infarctions (AMI) occur among people ages 18–55; a third of whom are women.1 The Variation in Recovery: Role of Gender on Outcomes of Young AMI Patients (VIRGO) study, a multi-site, prospective longitudinal study of U.S. and Spanish patients in this age group, was designed to investigate gender differences in trajectories of functional recovery including sexual activity and function in the year after AMI. In a one-month outcome study from VIRGO, and in another study including older AMI patients, most survivors were sexually active in the year before their event and many (40% of women, more than 55% of men) resumed sexual activity in the year afterwards.2,3 We have also found that patients with AMI of all ages value their sexual function and want to know what level of function to expect during recovery from AMI.2–4 Accordingly, U.S. and European AMI guidelines recommend that physicians counsel patients about resuming sex after AMI.5–7 Yet, little is known about patterns of sexual recovery or sexual problems after AMI, particularly for younger patients.

To inform patient counseling and expectations about sexual recovery, we describe, for the first time, patterns of, and gender differences in, sexual activity and problems among younger patients in the year after AMI. Our prior studies showed that women were less likely than men to receive counseling about sex after AMI, and demonstrated the importance of counseling for resumption of sexual activity.2,3 Extending these findings, we hypothesized that in the year after AMI: 1) women would be more likely than men to resume sexual activity late or not at all, and 2) women would be more likely than men to report sexual problems. We also examined predictors of loss of sexual activity in the year following AMI to determine potentially modifiable factors.

METHODS

Participants and Study Design

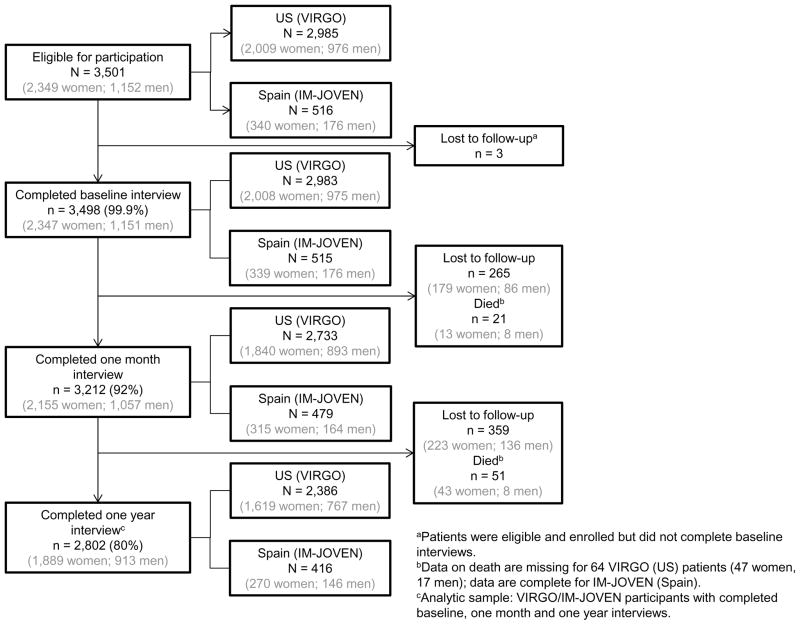

The VIRGO study has been previously described.8 Briefly, hospitalized patients with AMI ages 18–55 years were recruited between August 2008 and January 2012 to participate in VIRGO, named IM-JOVEN in Spain, to reflect separate, public funding (U.S.: N=2,985; 2,009 women, 976 men enrolled at baseline; 103 sites; Spain: N= 516; 340 women, 176 men enrolled at baseline; 24 sites). Eligible patients had increased cardiac biomarkers (preferably troponin), with at least one biomarker above the 99th percentile of the upper reference limit within 24 hours of admission. Additional evidence of acute ischemia was required, including at least one of the following: ischemia symptoms, electrocardiogram changes indicative of new ischemia (new ST-T changes, new or presumably new left bundle branch block, or the development of pathological Q waves). Patients must have presented directly to the enrolling site or been transferred within 24 hours of presentation to ensure primary clinical decision making occurred at the enrolling site. Patients who were incarcerated, did not speak English or Spanish, were unable to provide informed consent or be contacted for follow-up, developed elevated cardiac markers because of elective coronary revascularization, or had an AMI resulting from physical trauma were excluded. The overall participation rate was 65% among 5,422 meeting eligibility criteria (62% VIRGO, 88% IMJOVEN). The study sample was limited to 2,802 VIRGO participants with data at baseline, one month and one year (Figure 1). Institutional Review Board approval was obtained at each participating institution; patients provided informed consent to participate.

Figure 1.

Enrollment and Follow-Up of VIRGO Participants by Gender and Country

Data Collection

A detailed description of measures, including derived and calculated variables, is provided in eTable 1. Interviewers elicited demographic, psychosocial, and health characteristics at baseline, one month and one year. Self-reported race/ethnicity was assessed upon enrollment and analyzed as a potential predictor of sexual outcomes. Baseline interviews were conducted in-person during the index hospitalization; follow-up interviews were conducted via phone. Sexuality characteristics were measured using items adapted from prior large-scale interviewer-administered studies of adult sexuality.2,3,9,10 As in these prior studies, sexual activity was defined as “any mutually voluntary activity with another person that involves sexual contact, whether or not intercourse or orgasm occurs.” Refusal/missing rates for sexual activity, importance, frequency, function, and communication items were 0.2–8.6%; refusal/missing rates for attitudinal items (fear, interest in emotional closeness, initiation of sex, and sexual satisfaction) was 0.7–12%.

Statistical Analysis

This analysis used baseline, one month and one year data; 80% completed both one month and one year follow-up (Figure 1). Descriptive, bivariate analyses were used to compare gender differences in baseline and one year post-AMI demographic, psychosocial, and health characteristics; one year post-AMI sexual activity, sexual function and importance; and communication with a physician about sex since the AMI. Country-level comparisons were also made. Categorical data are presented as frequencies and percentages. Gender and country differences were compared using two-sided chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. Comparisons of doctor recommendations about sex between one month and the interval between one month and one year were also made, using McNemar’s test to take into account the correlations between these two time points. Continuous variables are reported as mean +/− standard deviation or median and 25%–75%; differences were compared using independent t tests and Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Patterns of partnership, sexual activity, patient-physician communication about sexual activity, and sexual problems over time were summarized overall and separately by gender.

Among those who were sexually active prior to the AMI, loss of sexual activity was classified into four groups (eTable 2): Group 1, defined as “early resumers” were those respondents who were sexually active in the 12 months before the AMI and at both one month and one year after AMI. Group 2, defined as “early resumers with later loss,” were those respondents who were sexually active in the 12 months before the AMI, had resumed sexual activity by one month after AMI, but did not report sexual activity at one year after AMI. Group 3, defined as “late resumers,” were those respondents who were sexually active in the 12 months before the AMI, had not resumed sexual activity by one month after AMI, but reported sexual activity at one year. Group 4, defined as “never resumers,” consisted of those respondents who were sexually active in the 12 months before their AMI who did not resume sexual activity at any time in the year following their AMI.

Bivariate analysis was first used to compare differences across these four groups. To further explore gender differences, multinomial logistic models were built and tested sequentially to assess how the gender effect was attenuated and identify predictors of loss of sexual activity in the year after AMI. Group 1 (early resumers) was the reference group; Group 2 was excluded due to the small sample size. The model covariates (eTable 1) were selected based on clinical judgment and their association with the outcome in prior studies: gender, age, country, partnership status, race, depression, stress, self-reported physical function, hypertension, diabetes, presence of at least one sexual problem, communication with a physician at one month post-AMI, and fearful of another heart attack at one year post-AMI.

Initially, eight models were tested using these covariates. Data from five models are presented in eTable 3; three models are presented here: 1) Model 1 included gender only; 2) Model 2 included gender and country, plus baseline demographic, psychosocial, and health characteristics, communication with a physician about sexual activity at one month, presence of at least one sexual problem at baseline, and fear of another heart attack at one year; and 3) Model 3 included all of the covariates included in Model 2 as well as two interactions: gender by partnership status and age by country. All interactions with gender and interactions between country and age, partnership status, and communication with physician at one month post-AMI, between communication with physician at 1 month post-AMI and fearful of another heart attack at one year post-AMI were tested, and non-significant interactions were removed from the final model (Model 3). To aid in interpretation of the model results, adjusted predicted probabilities of “early resumers,” “late resumers,” and “never resumers” were generated from Model 3 for partnered/un-partnered women and partnered/un-partnered men with other continuous covariates set to their mean and categorical variables set to their reference except for race which was held constant at white race. A generalized Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test for multinomial logistic regression models was conducted.11

Comparing participants in the VIRGO study to non-participants (those who completed screening but declined further participation), participants were more likely to be younger (median age 48 vs. 49 years), female (67% vs. 57%), and white (80% vs. 74%). Comparing the analytic sample for this study (limited to people who had baseline, one month, and one year data) to those who were excluded from the analytic sample due to insufficient data, those in the analytic sample were more likely to be older (median age 48 vs. 47 years), white (80% vs. 73%), and partnered (61% vs. 48%). The gender distribution was similar in the analytic sample (female 67%, male 33%) and those who were excluded (female 66%, male 34%).

P-values were two-sided and not adjusted for multiple testing. All analyses were conducted using SAS software, release 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) or Stata, release 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) and VIRGO data version 1.0.

RESULTS

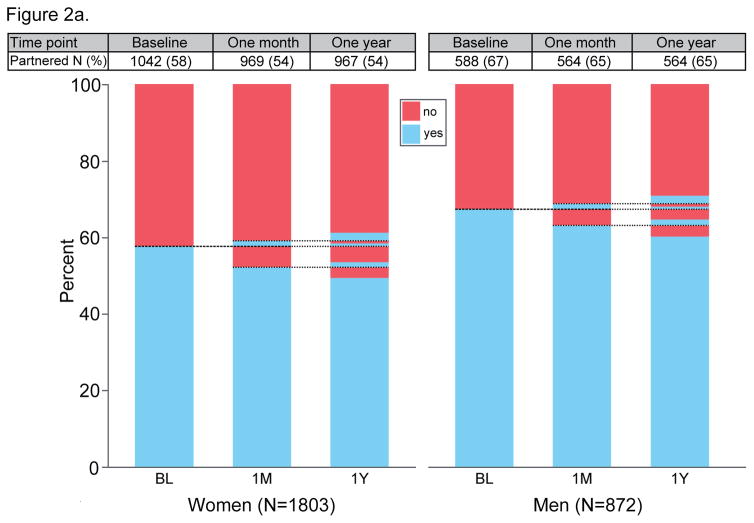

Table 1 summarizes participants’ baseline and, where appropriate, one year, demographic, psychosocial and health characteristics, by gender and country. Almost half of women (49%) and 60% of men were partnered at all three time points (Figure 2a). Although the age distribution was similar across gender and country groups, women (58% vs 67% of men at baseline; 53% vs 64% of men at one year) and U.S. patients (58% vs 73% of Spanish patients at baseline; 53% vs 77% of Spanish patients at 1 year) were less likely to be married or cohabiting (p<.001 for all comparisons) both at baseline and one year. Similar to baseline, both in the U.S. and Spain, women had higher rates of stress and depression at one year, and lower physical functioning as compared with men.

Table 1.

Characteristics of VIRGO Study Participants in the Analytic Samplea (stratified by gender)

| Overall (N=2802) | US (N=2386) | Spain (N=416) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Women (N=1889) | Men (N=913) | p-value | Women (N=1619) | Men (N=767) | p-value | Women (N=270) | Men (N=146) | p-value | |

| Demographics | |||||||||

| Baseline | |||||||||

| Age, median (25%–75%) | 49 (44–52) | 48 (44–52) | 0.15 | 49 (44–52) | 48 (44–52) | 0.15 | 47 (42–51) | 48 (43–51) | 0.98 |

| Race, N (%) | |||||||||

| White | 1455 (77) | 776 (85) | <.001 | 1200 (74) | 638 (83) | <.001 | 255 (95) | 138 (95) | 0.82b |

| Black | 334 (18) | 78 (9) | 328 (20) | 74 (10) | 6 (2) | 4 (3) | |||

| Other | 96 (5) | 58 (6) | 88 (5) | 55 (7) | 8 (3) | 3 (2) | |||

| Education, N (%) | |||||||||

| < High school | 113 (6) | 39 (4) | 0.13 | 32 (2) | 12 (2) | 0.58 | 81 (32) | 27 (21) | 0.04 |

| High school | 745 (40) | 350 (39) | 652 (41) | 297 (39) | 93 (37) | 53 (40) | |||

| > High school | 1001 (54) | 504 (56) | 924 (58) | 452 (59) | 77 (31) | 52 (39) | |||

| Partnership status, N (%) | |||||||||

| Married/Cohabitating/Committed relationship | 1083 (58) | 608 (67) | <.001 | 891 (55) | 501 (65) | <.001 | 192 (72) | 107 (76) | 0.49b |

| Divorced/Separated | 478 (25) | 166 (18) | 439 (27) | 150 (20) | 39 (15) | 16 (11) | |||

| Widowed | 76 (4) | 6 (1) | 68 (4) | 5 (1) | 8 (3) | 1 (1) | |||

| Single | 230 (12) | 124 (14) | 205 (13) | 108 (14) | 25 (9) | 16 (11) | |||

| Other | 15 (1) | 3 (0) | 12 (1) | 2 (0) | 3 (1) | 1 (1) | |||

| One Year | |||||||||

| Partnership status, N (%) | |||||||||

| Married/Cohabitating/Committed relationship | 970 (53) | 569 (64) | <.001 | 767 (50) | 454 (62) | <.001 | 203 (76) | 115 (79) | 0.16b |

| Divorced/Separated | 450 (25) | 146 (17) | 412 (27) | 133 (18) | 38 (14) | 13 (9) | |||

| Widowed | 70 (4) | 6 (1) | 63 (4) | 5 (1) | 7 (3) | 1 (1) | |||

| Single | 327 (18) | 161 (18) | 307 (20) | 144 (20) | 20 (7) | 17 (12) | |||

| Other | 2 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | |||

| Psychosocial Characteristics | |||||||||

| Baseline | |||||||||

| Stress,c Mean (SD) | 27 (10) | 23 (9) | <.001 | 27 (10) | 23 (9) | <.001 | 26 (10) | 22 (9) | <.001 |

| Depression,d N (%) | 694 (38) | 189 (21) | <.001 | 597 (38) | 164 (22) | <.001 | 97 (38) | 25 (18) | <.001 |

| One Year | |||||||||

| Stress,c Mean (SD) | 23 (9) | 19 (9) | <.001 | 22 (9) | 19 (9) | <.001 | 27 (10) | 21 (8) | <.001 |

| Depression,d N (%) | 391 (22) | 93 (11) | <.001 | 303 (20) | 77 (11) | <.001 | 88 (33) | 16 (11) | <.001 |

| Health Characteristics | |||||||||

| Baseline | |||||||||

| Diabetes, N (%) | 701 (37) | 237 (26) | <.001 | 617 (38) | 200 (26) | <.001 | 84 (31) | 37 (25) | 0.22 |

| Hypertension, N (%) | 1187 (63) | 554 (61) | 0.27 | 1066 (66) | 482 (63) | 0.15 | 121 (45) | 72 (49) | 0.38 |

| Physical Activity,e N (%) | |||||||||

| Recommended | 650 (35) | 383 (42) | <.001 | 558 (35) | 337 (44) | <.001 | 92 (34) | 46 (33) | 0.85 |

| Insufficient activity | 541 (29) | 241 (27) | 488 (30) | 210 (28) | 53 (20) | 31 (22) | |||

| Inactivity | 687 (37) | 281 (31) | 563 (35) | 217 (28) | 124 (46) | 64 (45) | |||

| AMI Severity,f Mean (SD) | 75.4 (18.2) | 73.1 (18.2) | 0.002 | 75.9 (18.6) | 73.5 (18.6) | 0.003 | 72.0 (15.4) | 70.7 (15.4) | 0.39 |

| Physical function, median (25%–75%) | 44 (34–54) | 50 (39–55) | <.001 | 43 (33–53) | 49 (38–55) | <.001 | 51 (42–56) | 54 (47–57) | 0.02 |

| One Year | |||||||||

| Physical Activity,e N (%) | |||||||||

| Recommended | 681 (38) | 452 (51) | <.001 | 546 (36) | 353 (48) | <.001 | 135 (51) | 99 (68) | <.001 |

| Insufficient activity | 571 (32) | 234 (27) | 533 (35) | 209 (29) | 38 (14) | 25 (17) | |||

| Inactivity | 554 (31) | 193 (22) | 461 (30) | 172 (23) | 93 (35) | 21 (15) | |||

| Physical function,g median (25%–75%) | 46 (35–54) | 52 (42–55) | <.001 | 46 (34–54) | 52 (41–56) | <.001 | 47 (38–52) | 52 (46–55) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: SD: Standard deviation;

Analytic sample is limited to those VIRGO participants with baseline, one month, and one year data.

Fisher’s exact test

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)

Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9≥10)

Inactivity defined as <10 minutes total per week of moderate- or vigorous-intensity activities; Insufficient activity defined as >10 minutes total per week of moderate- or vigorous-intensity activity, but less than the recommended level; and recommended physical activity defined as 150 minutes/week of moderate-intensity activity OR 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity OR an equivalent combination of moderate and vigorous activity.

Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) Risk Score

Short-Form Health Survey Physical Composite Score (SF-12 PCS)

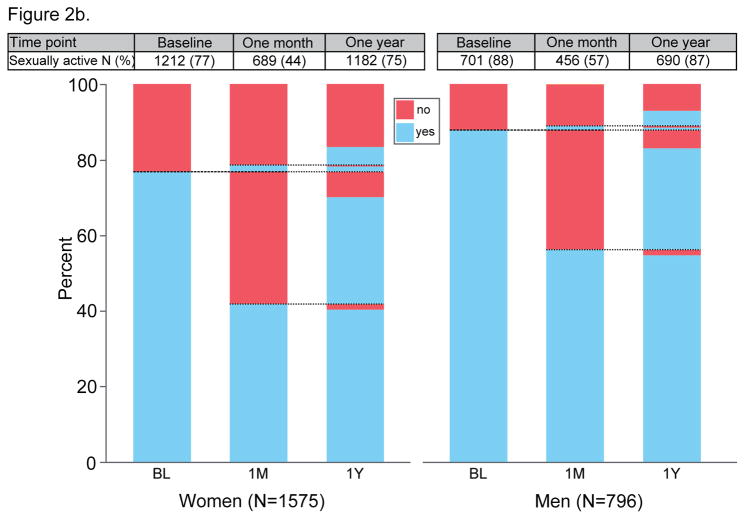

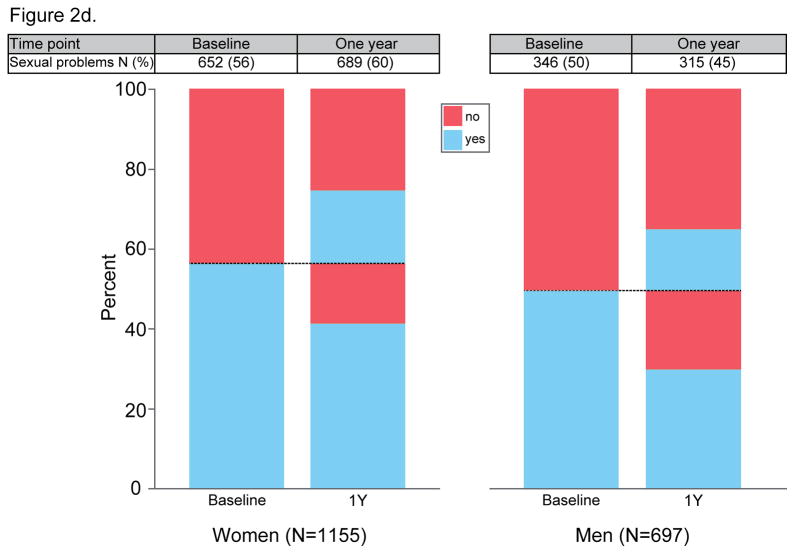

Figure 2. Patterns of partnership, resumption of sexual activity, patient-physician communication about sexual activity and sexual problems, by gender.

Figure 2a. Partnership at baseline, one month, and one year, by gender

Figure 2b. Sexual activity at baseline, one month, and one year, by gender

Figure 2c. Patient-physician communication about sex at one month and one year, by gender

Figure 2d. Sexual problems at baseline and one year, by gender

Overall, the majority of all women and men (73% vs 85%, p<.001) were sexually active one year after AMI (Table 2); 40% of women and 55% of men were sexually active at all three time points (Figure 2b). Among the subgroup of those who were sexually active at baseline, men were more likely than women to have resumed sexual activity by one month (64% versus 55%, p<0.001) and by one year (94% versus 91%, p=0.01) after AMI. Yet, patients in the U.S. were less likely to be sexually active at one year than those in Spain (75% vs 86%, p<.001). At one year, women were more likely to rate sex as “not at all important” (27% versus 8% of men, p<.001).

Table 2.

One Year Sexuality and Communication Characteristics of VIRGO Participants in the Analytic Samplea (stratified by gender)

| Overall (N=2802) | US (N=2386) | Spain (N=416) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women (N=1889) | Men (N=913) | p-value | Women (N=1619) | Men (N=767) | p-value | Women (N=270) | Men (N=146) | p-value | |

| Sexuality, N (%) | |||||||||

| Sexually active | 1255 (73) | 731 (85) | <.001 | 1035 (71) | 595 (84) | <.001 | 220 (82) | 136 (94) | 0.001 |

| Importance of sex | |||||||||

| Extremely/Very | 409 (24) | 389 (45) | <.001 | 344 (24) | 324 (46) | <.001 | 65 (24) | 65 (45) | <.001 |

| Moderately/Somewhat | 847 (49) | 403 (47) | 687 (47) | 324 (46) | 160 (60) | 79 (55) | |||

| Not at all | 472 (27) | 64 (8) | 428 (29) | 64 (9) | 44 (16) | 0 (0) | |||

| Fearful of another heart attackb | 257 (17) | 111 (14) | 0.05 | 214 (17) | 96 (14) | 0.14 | 43 (17) | 15 (11) | 0.10 |

| Interested in emotional closenessb | 724 (54) | 334 (46) | <.001 | 614 (56) | 286 (47) | 0.001 | 110 (49) | 48 (37) | 0.03 |

| Partner less likely to initiate sexb | 312 (24) | 205 (28) | 0.04 | 263 (24) | 168 (28) | 0.10 | 49 (22) | 37 (29) | 0.17 |

| Sexual satisfaction with significant otherc | 789 (86) | 488 (89) | 0.12 | 619 (86) | 378 (87) | 0.65 | 170 (86) | 110 (96) | 0.007 |

| Communication, N (%) | |||||||||

| Discussed sex with dr. since AMI | 330 (19) | 267 (31) | <.001 | 266 (19) | 208 (29) | <.001 | 64 (24) | 59 (41) | <.001 |

| Initiation of discussiond | |||||||||

| Patient | 195 (60) | 163 (61) | 0.92 | 170 (64) | 133 (64) | 0.80 | 25 (41) | 30 (52) | 0.33 |

| Doctor | 84 (26) | 65 (24) | 58 (22) | 42 (20) | 26 (43) | 23 (40) | |||

| Both | 47 (14) | 38 (14) | 37 (14) | 33 (16) | 10 (16) | 5 (9) | |||

| Doctor recommended:d | |||||||||

| Limit frequency of sex | 25 (8) | 34 (13) | 0.04 | 19 (7) | 27 (13) | 0.03 | 6 (10) | 7 (12) | 0.74 |

| Keep heart rate down during sex | 42 (13) | 29 (11) | 0.45 | 41 (15) | 26 (13) | 0.37 | 1 (2) | 3 (5) | 0.36e |

| Take more passive role during sex | 34 (11) | 37 (14) | 0.21 | 30 (11) | 30 (14) | 0.31 | 4 (7) | 7 (12) | 0.34 |

| Resume sex without limitations | 204 (62) | 139 (52) | 0.01 | 155 (58) | 111 (53) | 0.29 | 49 (78) | 28 (48) | <.001 |

| Take medications to help with sex | 14 (4) | 48 (18) | <.001 | 12 (5) | 41 (20) | <.001 | 2(3) | 7 (12) | 0.09e |

| Use relaxation techniques | 17 (5) | 13 (5) | 0.85 | 16 (6) | 7 (3) | 0.18 | 1 (2) | 6 (10) | 0.06e |

| Other recommendations | 38 (12) | 29 (12) | 0.80 | 33 (13) | 21 (10) | 0.44 | 5 (11) | 8 (18) | 0.35 |

| Satisfaction with doctor recommendationsd | |||||||||

| Not satisfied at all | 7 (2) | 8 (3) | 0.04 | 5 (2) | 3 (1) | 0.04 | 2 (3) | 5 (9) | 0.56e |

| Mostly dissatisfied | 12 (4) | 5 (2) | 8 (3) | 4 (2) | 4 (7) | 1 (2) | |||

| Somewhat satisfied | 19 (6) | 16 (6) | 16 (6) | 14 (7) | 3 (5) | 2 (4) | |||

| Mostly satisfied | 51 (16) | 66 (25) | 40 (15) | 55 (27) | 11 (19) | 11 (20) | |||

| Completely satisfied | 233 (72) | 168 (64) | 194 (74) | 131 (63) | 39 (66) | 37 (66) | |||

| Very/somewhat appropriate for physician to discuss sexual concerns | 1547 (90) | 812 (95) | <.001 | 1308 (90) | 675 (95) | <.001 | 239 (89) | 137 (97) | 0.01 |

| Very/somewhat comfortable discussing sexual issues with a physician | 1491 (86) | 796 (93) | <.001 | 1249 (85) | 659 (93) | <.001 | 242 (91) | 137 (96) | 0.06 |

| Characteristics of VIRGO Participants who Reported Sexual Activity in the Interval between One Month and 12 Months after AMI | |||||||||

| Sexual Frequency, N (%) | |||||||||

| Once per day or more | 13 (1) | 7 (1) | <.001 | 13 (1) | 7 (1) | <.001 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.24 |

| 3–6 times per week | 100 (8) | 82 (11) | 80 (8) | 64 (11) | 20 (9 ) | 18 (13) | |||

| 1–2 times per week | 430 (35) | 300 (42) | 316 (31) | 225 (38) | 114 (52) | 75 (55) | |||

| 2–3 times per month or less | 696 (56) | 333 (46) | 610 (60) | 290 (50) | 86 (39) | 43 (32) | |||

| Less Strenuous Sexb, N (%) | 386 (32) | 181 (26) | 0.003 | 319 (32) | 138 (24) | <.001 | 67 (31) | 43 (32) | 0.84 |

| Sexual Problems, N (%) | |||||||||

| Had at least one sexual problem | 727 (59) | 327 (46) | <.001 | 589 (59) | 270 (47) | <.001 | 138 (63) | 57 (42) | <.001 |

| Lacked interest | 487 (40) | 137 (19) | <.001 | 402 (40) | 119 (20) | <.001 | 85 (39) | 18 (13) | <.001 |

| Unable to experience orgasm | 236 (19) | 93 (13) | <.001 | 196 (20) | 84 (14) | 0.009 | 40 (18) | 9 (7) | 0.002 |

| Experienced orgasm too quickly (men only) | 101 (14) | 84 (14) | 17 (13) | ||||||

| Experienced physical pain | 120 (10) | 25 (4) | <.001 | 97 (10) | 21 (4) | <.001 | 23 (11) | 4 (3) | 0.009 |

| Experienced difficulty breathing | 239 (20) | 91 (13) | <.001 | 207 (21) | 82 (14) | <.001 | 32 (15) | 9 (7) | 0.02 |

| Did not find sex pleasurable | 166 (14) | 27 (4) | <.001 | 138 (14) | 24 (4) | <.001 | 28 (13) | 3 (2) | <0.001 |

| Felt anxious about sexual performance | 139 (11) | 113 (16) | 0.007 | 116 (12) | 99 (17) | 0.003 | 23 (11) | 14 (10) | 0.96 |

| Trouble getting or maintaining an erection (men only) | 156 (22) | 122 (21) | 34 (25) | ||||||

| Trouble lubricating (women only) | 273 (22) | 204 (20) | 69 (31) | ||||||

| Communication, N (%) | |||||||||

| Talked with partner re: sexual problemsf | 474 (66) | 223 (69) | 0.39 | 376 (65) | 177 (66) | 0.66 | 98 (73) | 46 (82) | 0.19 |

Analytic sample is limited to those VIRGO participants with baseline, one month, and one year data.

Agree or strongly agree (as compared to disagree/strongly disagree)

Of those who reported that they were married, cohabitating or in a committed relationship at one year, regardless of sexual activity status

Of those who had discussed sex with their doctor since their AMI

Fisher’s exact test

Of those who reported sexual problems

In both countries, women were less likely to receive counseling about resuming sex at any time in the year after AMI (27% versus 41% of men; p<.001; Figure 2c). Compared with patients in the U.S., Spanish patients were more likely to report having these discussions (30% vs. 22%, p<.001) and that a physician initiated these discussions (41% vs. 21%, p<.001). The recommendation to limit sex (21% vs.11%, p=0.01), keep heart rate down (16% vs. 10%, p=0.04) and take more passive role (24% vs.11%, p=0.002), were more commonly reported at one month than for the interval between one month and one year, while the recommendation to resume sex without limitations was less frequent at one month than for the interval between one month and one year (43% vs. 57%, p=0.02).

Among those who were sexually active in the 11 months following their one month interview, the majority of women (59%) and about half of men reported at least one sexual problem. Thirty-seven percent of sexually active patients with no sexual problems at baseline developed one or more incident sexual problems in the year after AMI (Figure 2d). The most prevalent sexual problems among women at one year were lack of interest (40%), trouble lubricating (22%), and difficulty breathing during intercourse (20%) while erectile difficulties (22%), lack of interest (19%), and feelings of anxiety about their sexual performance (16%) were the most prevalent among men. Few men (3% in the U.S. and 1.4% in Spain) reported use of medications to treat erectile dysfunction at baseline, one month, or one year after AMI.

Comparisons of the characteristics of the four resumption groups are provided in eTable 2. In unadjusted multinomial logistic regression analyses of loss of sexual activity in the year following an AMI, women were more likely to delay resuming sex (by one year rather than by one month or be a “late resumer”) compared with men (OR 1.45, 95% CI 1.15–1.81; p=0.001); this finding persisted even after controlling for other demographic, psychosocial, health, and sexual characteristics (Table 3; additional models in eTable 3). However, a significant gender by partnership status interaction was found (p=0.003): partnered women were more likely than partnered men to resume sex later (AOR 1.71, 95% CI 1.29–2.25; p<.001), but there was not a significant gender difference for un-partnered individuals. Older age among this younger cohort was also significantly associated with greater odds of being a “late resumer” in the U.S. (AOR 1.35, 95% CI 1.10–1.67; p=0.005) but not in Spain (AOR 0.75, 95% CI 0.50–1.12; p=0.16; age by country interaction p=0.01). Overall, those who had not communicated with a physician in the first month after their AMI were also more likely to be a “late resumer” (AOR 1.51, 95% CI 1.11–2.05; p=.008).

Table 3.

Gender Combined Models of Loss of Sexual Activity after an AMI among VIRGO Participants Who Were Sexually Active at Baseline (N=1492)

| Models | Covariates | Late Resumersa vs. Early Resumersa | Never Resumersa vs. Early Resumersa |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | ||

| Gender only | Female gender | 1.45 (1.15 – 1.81) | 1.62 (0.98 – 2.69) |

|

| |||

| All covariates | Female gender | 1.39 (1.10 – 1.76) | 1.29 (0.76 – 2.21) |

| Age at baseline (per 10 year increase) | 1.20 (1.00 – 1.45) | 1.58 (1.01 – 2.47) | |

| Spain (vs. US) | 1.20 (0.90 – 1.61) | 1.58 (0.83 – 2.99) | |

| Married/cohabitating/committed relationshipb (vs. not) | 0.76 (0.59 – 0.98) | 0.24 (0.14 – 0.40) | |

| White Race (vs. non-white) | 1.20 (0.84 – 1.71) | 1.31 (0.65 – 2.67) | |

| Stressb,c (per 10 point increase) | 1.11 (0.97 – 1.27) | 1.36 (1.01 – 1.84) | |

| Depressionb,d (vs. not) | 1.00 (0.74 – 1.34) | 1.17 (0.64 – 2.14) | |

| Physical functionb,e (per 10 point decrease) | 1.02 (0.92 – 1.14) | 1.08 (0.87 – 1.34) | |

| Hypertensionb (vs. not) | 1.19 (0.94 – 1.50) | 1.25 (0.72 – 2.18) | |

| Diabetesb (vs. not) | 1.05 (0.82 – 1.35) | 1.88 (1.14 – 3.11) | |

| Presence of at least 1 sexual problemf (vs. none) | 0.96 (0.76 – 1.21) | 1.47 (0.85 – 2.52) | |

| Communication with physician at one month--No (vs. Yes) | 1.48 (1.09 – 2.00) | 1.31 (0.66 – 2.61) | |

| Fearful of another heart attack at one year (agree/strongly agree vs. disagree/strongly disagree) | 0.99 (0.72 – 1.36) | 1.40 (0.78 – 2.50) | |

|

| |||

| All covariates plus significant interactionsg | White Race (vs. non-white) | 1.11 (0.77 – 1.59) | 1.33 (0.65 – 2.72) |

| Stressb,c (per 10 point increase) | 1.11 (0.97 – 1.27) | 1.36 (1.01 – 1.83) | |

| Depressionb,d (vs. not) | 0.96 (0.71 – 1.29) | 1.18 (0.65 – 2.17) | |

| Physical functionb,e (per 10 point decrease) | 1.02 (0.92 – 1.13) | 1.09 (0.88 – 1.34) | |

| Hypertensionb (vs. not) | 1.21 (0.96 – 1.54) | 1.24 (0.71 – 2.15) | |

| Diabetesb (vs. not) | 1.07 (0.84 – 1.38) | 1.90 (1.15 – 3.13) | |

| Presence of at least one sexual problemf (vs. none) | 0.95 (0.75 – 1.20) | 1.47 (0.86 – 2.53) | |

| Communication with physician at one month--No (vs. Yes) | 1.51 (1.11 – 2.05) | 1.31 (0.66 – 2.60) | |

| Fearful of another heart attack at one year (agree/strongly agree vs. disagree/strongly disagree) | 0.99 (0.72 – 1.35) | 1.40 (0.78 – 2.51) | |

| Gender x Married (partnered) interaction | |||

| Married vs. not, female | 1.01 (0.73 – 1.39) | 0.23 (0.13 – 0.42) | |

| Married vs. not, male | 0.45 (0.30 – 0.69) | 0.28 (0.11 – 0.68) | |

| Female vs. male, married | 1.71 (1.29 – 2.25) | 1.07 (0.51 – 2.24) | |

| Female vs. male, not married | 0.77 (0.49 – 1.21) | 1.29 (0.59 – 2.81) | |

| Age x Country interaction | |||

| Age for US | 1.35 (1.10 – 1.67) | 1.60 (0.97 – 2.63) | |

| Age for Spain | 0.75 (0.50 – 1.12) | 1.48 (0.57 – 3.82) | |

Early Resumers: Patient had resumed sexual activity by one month and continued to be sexually activity by one year; Late Resumers: Patient had not yet resumed sexual activity by one month, but had resumed by one year; Never Resumer: Patient did not resume sexual activity by one month or by one year.

Measured at baseline

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)

Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9≥10)

Short-Form Health Survey Physical Composite Score (SF-12 PCS)

Ascertained at the one month interview

Generalized Hosmer-Lemeshow Goodness-of-Fit test p=0.38

Among people who were sexually active in the year before AMI, women had higher odds of never resuming sexual activity in the year following AMI than men (OR 1.62, 95% CI 0.98–2.69), but this finding was not significant after controlling for other demographic, psychosocial, health, and sexual characteristics (AOR 1.29, 95% CI 0.76–2.21; Table 3). Older age, being un-partnered, higher stress levels, and having diabetes were all significant predictors of never resuming sexual activity in the year following AMI.

DISCUSSION

Our findings, based on two-country data from VIRGO, indicate that the vast majority of young women and men were partnered and sexually active in the year before and the year after AMI. More than half of women and just under half of men had sexual function problems in the year after AMI; women were more likely than men to develop incident sexual function problems. In spite of a high prevalence of sexual function problems, particularly among women, a minority reported having any conversation with a physician about resuming sex after AMI.

The proportions of patients who were partnered and sexually active at baseline were similar to those reported in population-based studies of similarly aged people in the U.S.12 and a slightly older population in Spain.13 In the first month following AMI, 7% of women and 4% of men became unpartnered and a similar proportion remained unpartnered at one year. Prior studies have shown that a person’s spouse or intimate partner is an important social relationship for recovery or protection from illness14,15 and that lower social support is associated with poorer AMI outcomes.16 Cardiac care providers should be aware that loss of a partner after AMI may impair the patient’s overall recovery and may require additional psychosocial support.

There was a significant drop in sexual activity at one month after AMI compared with baseline, followed by a significant increase between one month and one year for both men and women. Although the majority of people with AMI were sexually active by one year following, about one in ten women and one in twenty men never resumed sexual activity. In our earlier study by our group of an older U.S. cohort of 1,879 AMI patients (mean age 59.4 years), 11% of women and 13% of men had not resumed sexual activity by one year.2 Combining these findings, women with AMI and men older than 60 years can be counseled that about 90% do resume sexual activity by one year after AMI. Men younger than 60 can expect a 95% resumption rate by one year after AMI. Among partnered people, women resumed sexual activity later than men. Unpartnered people resumed sexual activity later than those with a partner. Overall, the majority had resumed sexual activity by one month. Patterns were similar in the U.S. and Spain.

Sexual function problems were prevalent before and after AMI in this cohort and generally higher than rates reported for the same age general population in the U.S.9 (we do not find comparable population-based data from Spain). A large proportion of women (42%) and men (30%) with no baseline sexual problems developed one or more incident sexual problems in the year after AMI. The rate of loss of sexual function after AMI was on a par with the loss of general physical function in this cohort (46% of people with the recommended level of physical activity at baseline had insufficient activity or inactivity at one year) and was several fold higher than the incidence of depression after AMI (10%). While it is important to advise patients that sexual problems may arise after AMI (most commonly lack of interest for women and erectile difficulties for men), cardiac care providers can also give hope by communicating that 40% of women and 55% of men have no sexual function problems in the year after AMI, and that nearly a third of patients with problems in the year before AMI reported none in the year after.

Our prior studies in the U.S. and Spain have shown that communication with a physician is significant predictor of sexual activity after AMI.2,3 As expected, communication rates at one year were higher for both women and men than reported at one month, but still low. Spanish patients were more likely to report having these discussions and that a physician initiated these discussions. The nature of physician counseling changed over time; physicians in both the U.S. and Spain were more cautious in their counseling about sexual activity earlier on. This study shows that counseling was a significant predictor of time to resumption (early versus late), but stress and diabetes more strongly predicted never resuming sexual activity. These health conditions are known to have deleterious effects on overall outcomes after AMI17 as well as on male and female sexual function.9,17 Counseling patients that these conditions predict poorer sexual function outcomes might help motivate adherence to cardiac rehabilitation, lifestyle changes, and other secondary prevention activities.

The study findings should be interpreted in the context of several potential limitations. This study relied on patient self-report, which may have introduced recall bias. In our prior study, recall of discharge instructions about resuming sexual activity, as compared with documentation in the medical chart, did not differ by gender or sexual activity in the year following AMI.2 Statistically significant differences in demographic characteristics were found between VIRGO participants and non-participants, and between those in our analytic sample and those excluded, but differences were small. Given the importance of gender in our analyses, it is reassuring that there the distribution of gender was similar between the analytic sample and those who were excluded due to insufficient data. Nevertheless, a higher proportion of partnered people in the analytic sample could produce upward bias on the sexual activity and sexual problem estimates. Although partner factors can affect resumption of sexual activity after AMI,4 partner data were not collected. This study did not collect qualitative data. However, prior qualitative research corroborates that sexual problems after AMI are prevalent, fear could inhibit resumption, and patients want to be counseled about sex after AMI by their physician.4 Lastly, a larger sample size and additional data would be needed to stratify by sexual orientation or identity, partner gender, model the effects on sexual outcomes of specific comorbidities, medications, procedures, tests, and effects of rehabilitation, prolonged or re-hospitalization or a subsequent AMI or other health event. Understanding the impact of these factors on sexual outcomes could allow for more tailored counseling according to individual risk for loss of sexual activity or function after AMI.

Patients want to know what level of sexual function to expect during recovery from AMI. Our findings can be used to expand counseling and care guidelines5–7 to include advising patients on what to expect in terms of post-AMI sexual activity and function. Attention to modifiable risk factors and improved physician counseling may be important levers for improving sexual function outcomes for young women and men after AMI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr. Lindau reported receiving NIH grant support (1K23AG032870-01A1K23) and philanthropic funds to the Lindau Laboratory for this study; Ms. Abramsohn and Ms. Wroblewski are also supported by these mechanisms. Dr. Lindau, Ms. Abramsohn and Ms. Wroblewski report no other disclosures. Dr. Krumholz is a recipient of research agreements from Medtronic and from Johnson & Johnson (Janssen), through Yale University, to develop methods of clinical trial data sharing and is chair of a cardiac scientific advisory board for UnitedHealth. Dr. Bueno was supported in part by grant BA08/90010 from the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria del Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain and has received advisory/consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, BMS-Pfizer, Daichii-Sankyo, Eli-Lilly, Ferrer, Menarini, Novartis, and Servier. Dr. Mehta Sanghani is on the advisory board and speaker’s bureau for Astellas Pharma, Inc. Dr. Spatz is supported by grant K12HS023000 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Patient Centered Outcomes Research (PCOR) Institutional Mentored Career Development Program. Dr. Spertus is a member of the cardiac scientific advisory board for United Healthcare, has research grants from NIH, Genentech, Gilead, ACCF, Lilly, has provided consulting services for Novartis, Amgen, Gilead, Janssen and owns the copyright to the Seattle Angina Questionnaire. All other authors report no disclosures.

Funding sources: Dr. Lindau, Ms. Abramsohn and Ms. Wroblewski were supported by grant 1K23AG032870-01A1K23 and by philanthropic funds to the Lindau Laboratory at the University of Chicago; Dr. Krumholz is supported by grant U01 HL105270-05 (Center for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research at Yale University) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Spatz is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Patient Centered Outcomes Research (PCOR) Institutional Mentored Career Development Program (K12HS023000). VIRGO was supported by grant R01 HL081153 from the National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute, Department of Health and Human Services. IMJOVEN was supported in Spain by PI 081614 from the Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias del Instituto Carlos III, Ministry of Science and Technology, and additional funds from the Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: Contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the National Institute on Aging. The funders of this study had no role in the design and conduct of the study, the collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data, or the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Access to Data and Data Analysis: Ms. Strait (Yale University) and Ms. Zhou (Yale University) conducted the data analyses. Ms. Strait and Ms. Zhou had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Contributor Information

Stacy Tessler Lindau, University of Chicago.

Emily Abramsohn, University of Chicago.

Hector Bueno, Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC), Instituto de investigación i+12 and Cardiology Department, Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Spain.

Gail D’Onofrio, Yale University School of Medicine.

Judith H. Lichtman, Yale School of Public Health.

Nancy P. Lorenze, Yale University.

Rupa Mehta Sanghani, Rush University Medical Center.

Erica S. Spatz, Yale University School of Medicine.

John A. Spertus, Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute/University of Missouri-Kansas City.

Kelly M. Strait, Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation.

Kristen Wroblewski, University of Chicago.

Shengfan Zhou, Yale University.

Harlan M. Krumholz, Yale School of Medicine.

References

- 1. [Accessed November 14, 2013];National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. 2009–2012 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes_questionnaires.htm.

- 2.Lindau S, Abramsohn E, Gosch K, et al. Patterns and loss of sexual activity in the year following hospitalization for myocardial infarction: A U.S. national, multi-site observational study. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109(10):1439–1444. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.01.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindau ST, Abramsohn EM, Bueno H, et al. Sexual activity and counseling in the first month after acute myocardial infarction among younger adults in the United States and Spain: a prospective, observational study. Circulation. 2014;130(25):2302–2309. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abramsohn E, Decker C, Garavalia B, et al. “I’m not just a heart, I’m a whole person here”: A qualitative study to improve sexual outcomes in women with myocardial infarction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(4) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson J, Adams C, Antman E, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(19):e215–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levine G, Steinke E, Bakaeen F, et al. Sexual activity and cardiovascular disease: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(8):1058–1072. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182447787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steg P, James S, Atar D, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(20):2569–2619. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lichtman J, Lorenze N, D’Onofrio G, et al. Variation in Recovery Role of Gender on Outcomes of Young AMI Patients (VIRGO) Study Design. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3(6):684–693. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.928713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laumann E, Paik A, Rosen R. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: Prevalence and predictors. JAMA. 1999;281(6):537–544. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Levinson W, O’Muircheartaigh CA, Waite LJ. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. New Engl J Med. 2007;357(8):762–774. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fagerland MW, Hosmer DW, Bofin AM. Multinomial goodness-of-fit tests for logistic regression models. Stat Med. 2008;27(21):4238–4253. doi: 10.1002/sim.3202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chandra A, Mosher W, Copen C. Sexual behavior, sexual attraction, and sexual identity in the United State: Data from the 2006–2008 National Survey of Family Growth. Hyattsville, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moreira E, Glasser D, Gingell C. Sexual activity, sexual dysfunction and associated help-seeking behaviours in middle-aged and older adults in Spain: a population survey. World J Urol. 2005;23:422–429. doi: 10.1007/s00345-005-0035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hughes ME, Waite LJ. Marital biography and health at mid-life. J Health Soc Behav. 2009;50(3):344–358. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waite L, Das A. Families, social life and well-being at older ages. Demography. 2010;47s:s87–s109. doi: 10.1353/dem.2010.0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leifheit-Limson EC, Reid KJ, Kasl SV, et al. The role of social support in health status and depressive symptoms after acute myocardial infarction: evidence for a stronger relationship among women. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3(2):143–150. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.899815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cummings DM, Kirian K, Howard G, et al. Consequences of comorbidity of elevated stress and/or depressive symptoms and incident cardiovascular outcomes in diabetes: Results from the REasons for the Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) Study. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(1):101–109. doi: 10.2337/dc15-1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.