Abstract

Objective:

In this report, we placed focus on the immunological function of lymph nodes and performed lymph node transfer via a free flap to a site of refractory infection.

Case and Results:

Case 1 describes a 34-year-old male suffering from compound fractures with severe crush injuries and burns in the right ankle joint. A 20 × 15 cm skin defect was observed around the right malleolus medialis, along with denuded tendons with bacterial infection. After conservative treatment, we transferred a lymph-node-containing free superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator flap to the region, with minimum debridement. No recurrence of wound infection appeared. Case 2 describes a 73-year-old male patient suffering from extensive contused wound in the right crus. Despite conservative treatment, the tibia gradually became denuded with computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging revealing degeneration of the tibial cortex. We performed a free superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator flap containing lymph nodes to the chronic infection area. The wound area healed successfully.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, lymph node transfer has a potential of treatment infection sites.

Keywords: Surgery, lymphedema, lymph node transfer, infection

Introduction

Complete debridement and overlaying the wound using blood-rich tissue flaps are the standard treatment procedures for treating trauma with associating chronic and refractory infections or osteomyelitis complications that are resistant to long-term conservational therapy.1,2 Preserving the denuded bone or tendon in the wound area would often lead to difficulties in infection control, subsequently resulting in extensive debridement. Especially in cases of limb injury with joint or tendon infections, possible functional impairment may be caused by the debridement process, consequently lowering the patient’s quality of life.3,4

Lymph node transfer is an effective surgical treatment for lymphedema of the extremities.5–8 The transplanted lymph node facilitates lymphangiogenesis in the region, regenerating the lost lymphatic vessels and restoring lymph flow in the area.5,6 Moreover, there have been reports suggesting the existence of physiological lymphatic-venous anastomosis within a lymph node,7,8 possibly granting its ability to relieve abnormal lymph congestion in the extremities when transplanted. In an earlier study, we have reported that lymph node transfer via a free flap may assist in the early diagnosis of cancer metastasis in a post-cancer patient after head and neck reconstruction surgery. The transferred node acts as the sentinel lymph node, and early diagnosis of metastasis can be achieved by examining that node periodically.9

In this report, we placed focus on the immunological function of lymph nodes and performed lymph node transfer via a free flap to a site of refractory infection.

Patient summary

Case 1

A 34-year-old male patient suffered compound fractures with severe crush injuries and burns in the right ankle joint from a traffic accident. The patient was first brought to the emergency room and was treated using negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT); however, trauma site infection appeared after 4 days and he was transferred to our department (Figure 1). Examination of the patient revealed a 20 × 15 cm skin defect around the right malleolus medialis, along with denuded tibialis posterior tendon (TPT) and flexor digitrum longus tendon (FDLT), and an active site of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Skin ulceration was also present in the area and on the dorsum pedis. Orthopedic surgery was recommended to cover the TPT and FDLT denudation in addition to extensive debridement around the ankle joint. Debridement of the necrotic tissue caused by the burn injury was performed by our department 5 weeks after the initial accident and wound cleaning was continued for an additional period of time. The lymph node transfer surgery was planned 8 weeks after the accident using a lymph-node-containing free superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator flap from the left inguinal area. Since the patient suffered an open ankle wound and prolonged denudation of the TPT and FDLT, functional impairment was a risk; therefore, debridement around the joint was kept to a minimum in order to focus on preserving joint functionality. Subcutaneous indocyanine green (ICG) injections were performed pre-operatively at two sites around the left anterior superior iliac spine area. ICG lymphography was then performed to identify the lymph flow and the inguinal lymph nodes in the left inguinal region (Figure 2(b)). An 8 × 15 cm free tissue flap was harvested containing two lymph nodes (Figure 2(c)) and the flap was anastomosed to the branches of the anterior tibial artery and vein. Additionally, a split-thickness skin graft was harvested from the right gluteal region and was used to cover the remaining skin defect in the wound area. An arterial thrombus appeared the day after the surgery and thrombectomy followed by blood vessel reconstruction was performed. No other post-operative complication was observed and the flap and skin graft had attached successfully (Figure 3(a)). After a post-operative period of 2.5 years, the ankle joint function and toe flexion movements suffered only minimal impairment (Figure 3(b)) and the patient had recovered to a point where he could play soccer without any problems. No recurrence of wound infection appeared in the right ankle and the donor site did not present any lymphedema-like symptoms. Post-operative ICG lymphography confirmed the accumulation of ICG in the transplanted lymph nodes within the flap, indicating the lymph node had successfully attached to the recipient area (Figure 3(b)).

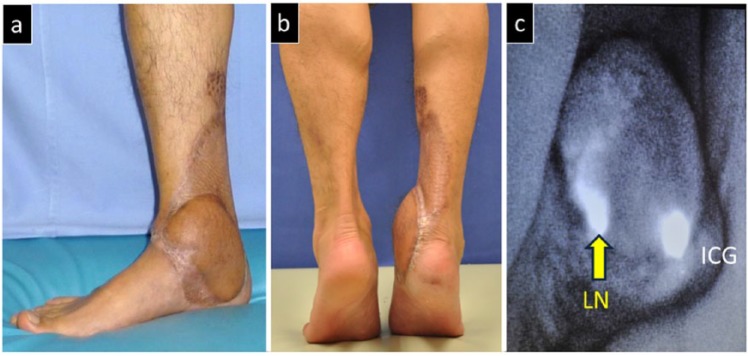

Figure 1.

Case 1. (a) Gross appearance of the wound. Open fracture and attachment of necrotic tissue and associating Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection can be seen. (b) X-ray image at the time of first medical examination. Degeneration of the tibial cortex is observed.

Figure 2.

Intra-operative view of Case 1. (a) View after the debridement process. The denuded tibialis posterior tendon and flexor digitrum longus tendon are preserved as much as possible. (b) Indocyanine green was injected at two sites around the left anterior superior iliac spine area to identify the left inguinal lymph nodes. (c) The flap was made and raised to include the identified lymph nodes.

ICG: indocyanine green; LN: lymph node.

Figure 3.

Post-operative view of Case 1. (a) Complete epithelialization of the wound is observed after a 10-month post-operative follow-up. (b) The functional impairment in the ankle joint is kept to a minimum. The patient is able to stand on tiptoes. (c) Post-operative ICG imagining shows accumulation of ICG in the transplanted lymph nodes, thus confirming the attachment of the nodes.

ICG: indocyanine green; LN: lymph node.

Case 2

A 73-year-old male patient suffered extensive contused wound in the right crus during infancy while skiing. Despite conservative treatment in dermatology; the tibia gradually became denuded and the wound failed to heal; hence, the patient was consulted to our department. Examination revealed a 15 × 3 cm wide scar in the right tibial area, within which there were two ulceration sites with pus-like discharge (Staphylococcus aureus (2+), Enterobacter aerogenes (1+), Strebtococcus agalactiae (1+)) (Figure 4(a)). The cranial and caudal ulceration were 0.8 × 0.6 cm and 0.4 × 0.4 cm in size, respectively. Both ulceration sites presented bone denudation and computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) also revealed degeneration of the tibial cortex. The patient had no history of any other diseases or lower limb ischemia which could delay the wound healing process. Since conservative therapies failed to show improvement, we performed lymph node transfer using a free superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator flap containing lymph nodes from the left inguinal region in hopes to endow the immunological function of lymph nodes on the chronic infection area. Intra-operative ICG lymphography was performed to identify the lymph nodes at the donor site. The excess tissue in the anterior part of the tibia was shaved off (Figure 4(b)) and the bare area was covered by the 5 × 8 cm flap (Figure 5). The perforator branches of the peroneal artery and vein were used as the recipient vessels that were anastomosed end-to-end with the vessels of the flap. No post-operative complications were observed and the wound area healed successfully (Figure 6). After a post-operative period of 2 years and 8 months, the donor site did not present any lymphedema-like symptoms and ICG lymphography on the right crus did not reveal any abnormal lymph congestion. No recurrence of wound infection appeared in the area.

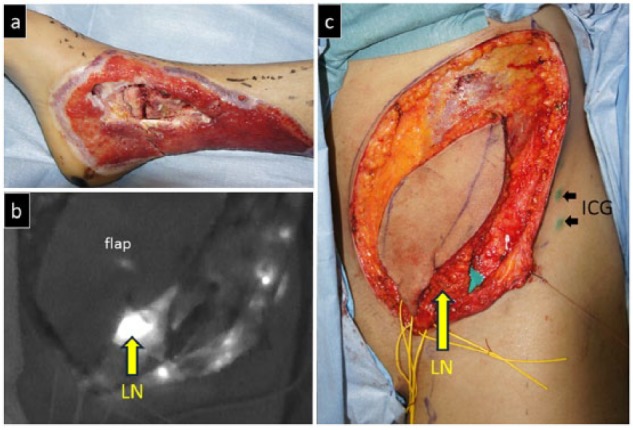

Figure 4.

Case 2. (a) Pre-operative view showing an extensive contused scar and refractory ulcerations in the anterior right crus. Bone denudation is also observed under the ulcerations. (b) Intra-operative view of the ulceration sites. Partial debridement of the exposed anterior side of the tibia is performed.

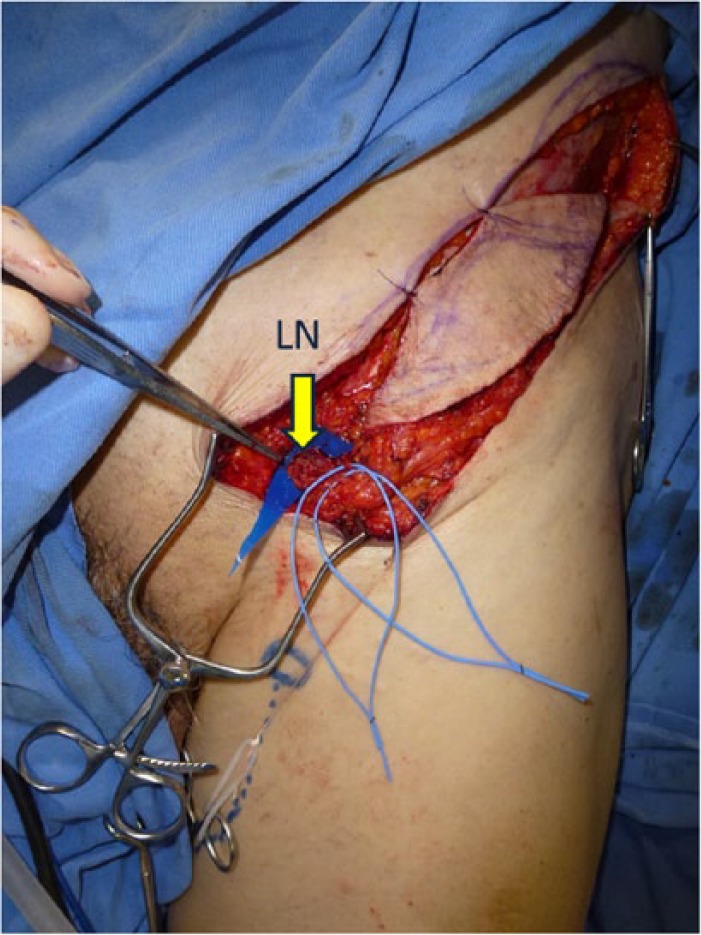

Figure 5.

Intra-operative view of Case 2. A superficial circumflex iliac artery flap containing lymph nodes was harvested from the left inguinal area.

LN: lymph node.

Figure 6.

Post-operative view of Case 2 after 29 months. Complete epithelialization of the scar is observed and skin ulcerations and osteomyelitis complications have ceased.

Discussion

In this study, we performed minimal debridement and lymph node transfer via a free flap to a trauma area with chronic refractory infection and have observed a successful recovery of the wound. It is possible that such wound recovery feature of lymph node transfer may be contributed by the immunological function of the transplanted lymph nodes.

Conventional treatments for wounds with refractory ulcerations or osteomyelitis are mainly conservative therapies involving the use of ointment remedy followed by 4–6 weeks of systemic antibacterial treatment and hyperbaric oxygen therapy.1,2 If the wound is non-responsive to the conservative therapies, surgical treatments including complete amputation and overlaying the wound with a free or pedicle flap often become necessary.10,11 Complete amputation of the infected area improves the infection control of the region; however, it may consequently lead to irreversible functional impairments. Moreover, in the case of chronic osteomyelitis, it is known that complete debridement is not sufficient to make the wound area bacteria-free, and pus discharge may recur after temporary remission.12

In this case, we reported the complete recovery of a wound with refractory infection and ulceration while minimizing functional impairment by keeping the debridement procedure to a minimum in order to conserve the denuded bone and tendon in addition to overlaying the wound with a tissue flap containing lymph nodes to control infection. In both cases, a thorough debridement and coverage with healthy tissue would be enough to treat the exposed and infected bone. The impact of the lymph node transfer is controversial in the resolution of the infection, which may be due to the coverage with the free fasciocutaneous groin flap itself. At least, in the present cases, although we performed only minimal debridement to maintain the walking capability, the infection was successfully controlled. Our results could suggest that lymph node transfer on wound areas with poorly controlled infections, such as due to prolonged tendon denudation or osteomyelitis, may enhance the local immunity of the area in assisting infection control.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the total cooperation received from Eri Saeki, Izumi Masuda, Sachiko Kimura, Kyoko Hasegawa, Hiroshi Minezaki, Takiko Suzuki, Naomi Yamada, and Shigeru Harasawa (Saiseikai Kawaguchi General Hospital). M.M. and H.H. contributed equally to this work.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval to report this case was obtained from Institutional Review Board (Saiseikai Kawaguchi General Hospital Ethical Review Board, approval code: 22-12, Tokyo University Ethical Review Board).

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient(s) for their anonymized information to be published in this article.

References

- 1. Anakwenze OA, Milby AH, Gans I, et al. Foot and ankle infections: diagnosis and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2012; 20(11): 684–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kadam D. Limb salvage surgery. Indian J Plast Surg 2013; 46(2): 265–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Napierala MA, Rivera JC, Burns TC, et al. ; Skeletal Trauma Research Education Consortium (STReC). Infection reduces return-to-duty rates for soldiers with Type III open tibia fractures. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2014; 77(3 Suppl. 2): S194–S197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Thein R, Tenenbaum S, Chechick O, et al. Delay in diagnosis of femoral hematogenous osteomyelitis in adults: an elusive disease with poor outcome. Isr Med Assoc J 2013; 15(2): 85–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Saaristo AM, Niemi TS, Viitanen TP, et al. Microvascular breast reconstruction and lymph node transfer for postmastectomy lymphedema patients. Ann Surg 2012; 255(3): 468–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mihara M, Zhou HP, Hara H, et al. Case report: a new hybrid surgical approach for treating mosaic pattern secondary lymphedema in the lower extremities. Ann Vasc Surg 2014; 28(7): 1798.e1–1798.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Becker C, Assouad J, Riquet M, et al. Postmastectomy lymphedema: long-term results following microsurgical lymph node transplantation. Ann Surg 2006; 243(3): 313–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Patel KM, Lin CY, Cheng MH. A prospective evaluation of lymphedema-specific quality-of-life outcomes following vascularized lymph node transfer. Ann Surg Oncol 2015; 22: 2424–2430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mihara M, Iida T, Hara H, et al. Autologus groin lymph node transfer for “sentinel lymph network” reconstruction after head-and-neck cancer resection and neck lymph node dissection: a case report. Microsurgery 2012; 32(2): 153–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Klebuc M, Menn Z. Muscle flaps and their role in limb salvage. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J 2013; 9(2): 95–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rubino C, Figus A, Mazzocchi M, et al. The propeller flap for chronic osteomyelitis of the lower extremities: a case report. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2009; 62(10): e401–e404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Costa-Reis P, Sullivan KE. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis. J Clin Immunol 2013; 33(6): 1043–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]