Abstract

PURPOSE

Immune checkpoint inhibition reactivates the immune response against cancer cells in multiple tissue types and has been shown to induce durable responses. However, for patients with autoimmune disorders, their conditions can worsen with this reactivation. We sought to identify, among patients with lung and renal cancer, how many harbor a comorbid autoimmune condition and may be at risk of worsening their condition while on immune checkpoint inhibitors such as nivolumab and pembrolizumab.

METHODS

An administrative health care claims database, Truven MarketScan, was used to identify patients diagnosed with lung and renal cancer from 2010 to 2013. We assessed patients for diagnosis of autoimmune diseases 1 year prior to or after diagnosis of cancer using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes for 41 autoimmune diseases. Baseline characteristics and other comorbid conditions were recorded.

RESULTS

More than 25% of patients with both lung and renal cancer had a comorbid autoimmune condition between 2010 and 2013 and were more likely to be women, older, and have more baseline comorbidities.

CONCLUSIONS

This population presents a dilemma to physicians when deciding to treat with immune checkpoint inhibitors and risk immune-related adverse events. Future evaluation of real-world use of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with cancer with autoimmune diseases will be needed.

Keywords: Autoimmune disease, immune checkpoint inhibitors, lung cancer, renal cancer, epidemiology

Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are designed to restore a patient’s antitumor immune response, which has been attenuated during the process of tumor development. Antigen-presenting cells normally express programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) that, when bound by PD-1 on T cells, signal an exhausted active immune response. In cancers that express PD-L1 on tumor cells, PD-1 receptor expressed on T cells, B cells, and natural killer cells of an activated immune system, and the interaction of PD-1 and PD-L1 characterizes an adaptive and immune-evasive response by the tumor. This immune-evasive interaction can be reversed by addition of ICIs that inhibit either molecule.1 Recently, agents that modulate the tumor immune response have provided durable clinical benefit to patients with late-stage or recurrent disease. Nivolumab (Opdivo) has received Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for the treatment of squamous and nonsquamous metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and metastatic renal cell carcinoma with progression on or after chemotherapy.2 Nivolumab is a human IgG4 antibody that blocks programmed death 1 (PD-1) receptor and potentiates activation of T cells.3 Nivolumab therapy demonstrated improved tumor-related outcomes in multiple types of cancer.4 Pembrolizumab (Keytruda), another PD-1 inhibitor, received FDA approval to treat advanced (metastatic) NSCLC whose disease has progressed after other treatments and with tumors that have 50% PD-L1 expression.5

Programmed death ligand 1 inhibition facilitates activation of potentially autoreactive T cells, leading to inflammatory adverse events across a range of tissues. Patients with a history of autoimmune diseases were excluded from clinical trials of PD-1 inhibitors.6 Exclusions included multiple sclerosis, autoimmune neuropathy, Guillain-Barré syndrome, myasthenia gravis, systemic lupus erythematosus, connective tissue diseases, scleroderma, inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, and hepatitis. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome, and psoriasis were included if disease was well-controlled. Although these therapies hold great promise, ICIs can trigger a variety of immune-related adverse events (irAEs). These include dermatologic, gastrointestinal, hepatic, endocrine, and other inflammatory conditions, and they are believed to result from general immune response enhancement.7 Khan et al8 have shown a relatively high rate of autoimmune diseases, approximately 14%, among patients with lung cancer, and these patients were more likely to be older women. The objective of this study was to confirm findings of Khan and colleagues in a more diverse cohort and identify whether patients with cancer with autoimmune disease exhibit different baseline characteristics and comorbidities.

Materials and Methods

We identified lung patients with and renal cancer using Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Medicare Supplemental Database. The MarketScan database includes approximately 40 million individuals from more than 160 large employers and health plans across the United States and includes health care claims with diagnosis and procedure codes for medical encounters and all prescription medication fills. These data are de-identified in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations, and the University of Kentucky Institutional Review Board approved the use of the database for this study.

Adults, 18 years and older, diagnosed with cancer between January 1, 2010 and November 31, 2013 were identified. At least 2 inpatient or outpatient diagnoses separated by at least 14 days were required, and the date of the first qualifying diagnosis of cancer was defined as the index date. We directed our analyses to only lung and renal cancer due to the initial approvals of the ICI, nivolumab. Nivolumab received approval for the treatment of metastatic NSCLC on March 4, 2015 and for metastatic renal cell carcinoma on November 23, 2015. Patients were required to have at least 12 months of preindex and a minimum of 1-month postindex continuous enrollment in the database. We assessed patients for diagnosis of autoimmune diseases prior to or after diagnosis of cancer using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes for 41 autoimmune diseases. It is necessary to assess autoimmune disease before and after diagnosis because newly diagnosed autoimmune conditions would still have bearing on therapeutic decision-making practices. Prevalence was determined by the presence of 2 or more claims to autoimmune diseases separated by at least 30 days. Baseline characteristics and Elixhauser and Charlson comorbidity indexes of patients with and without autoimmune diseases were compared. These indexes include 17 and 31 categories of comorbid conditions, respectively, and have been widely used for risk adjustment with health outcomes data.9,10 Two-sample t test and χ2 tests were conducted to assess significant differences between groups. Bonferroni correction was applied due to multiple comparisons.

Results and Discussion

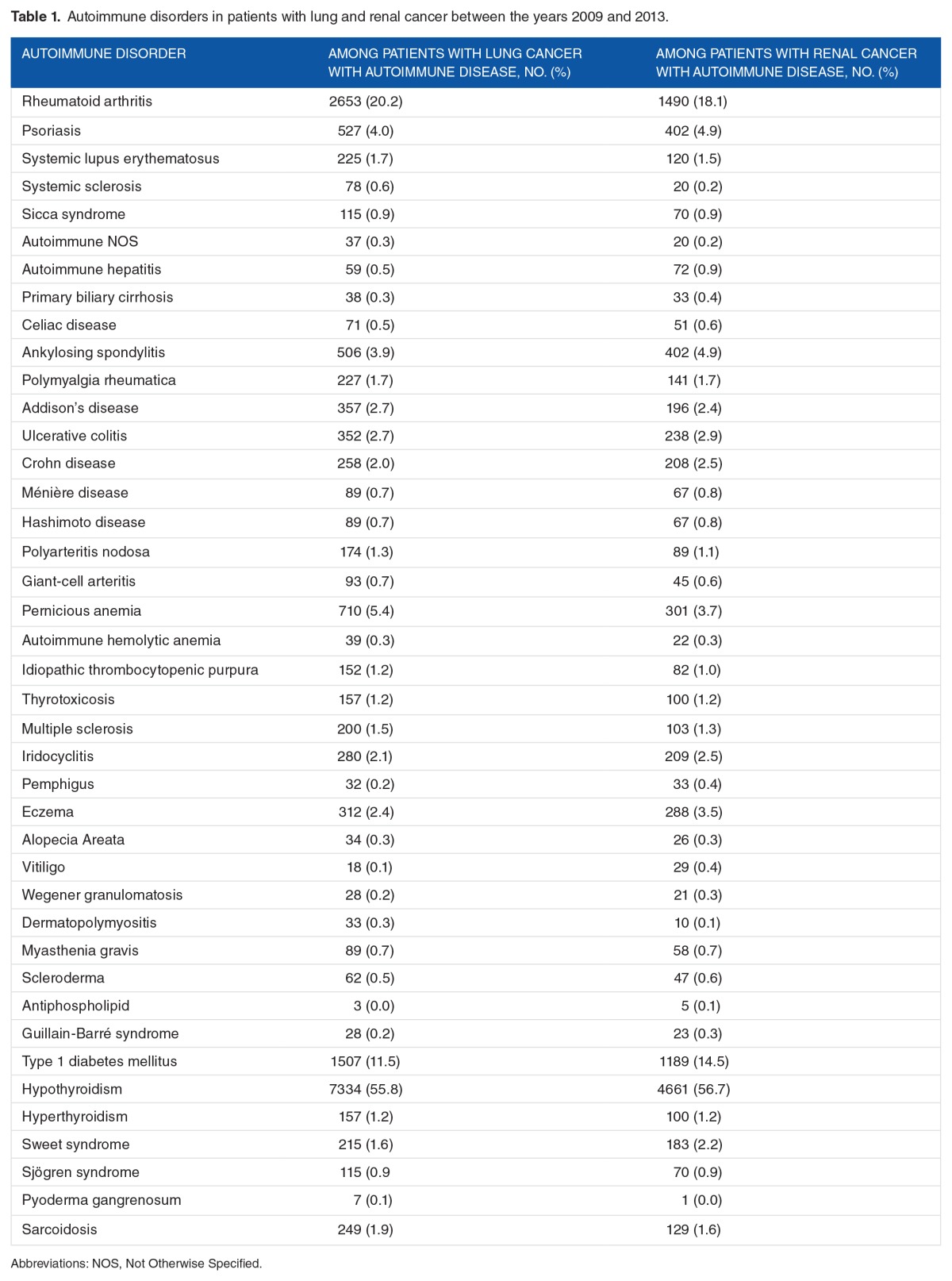

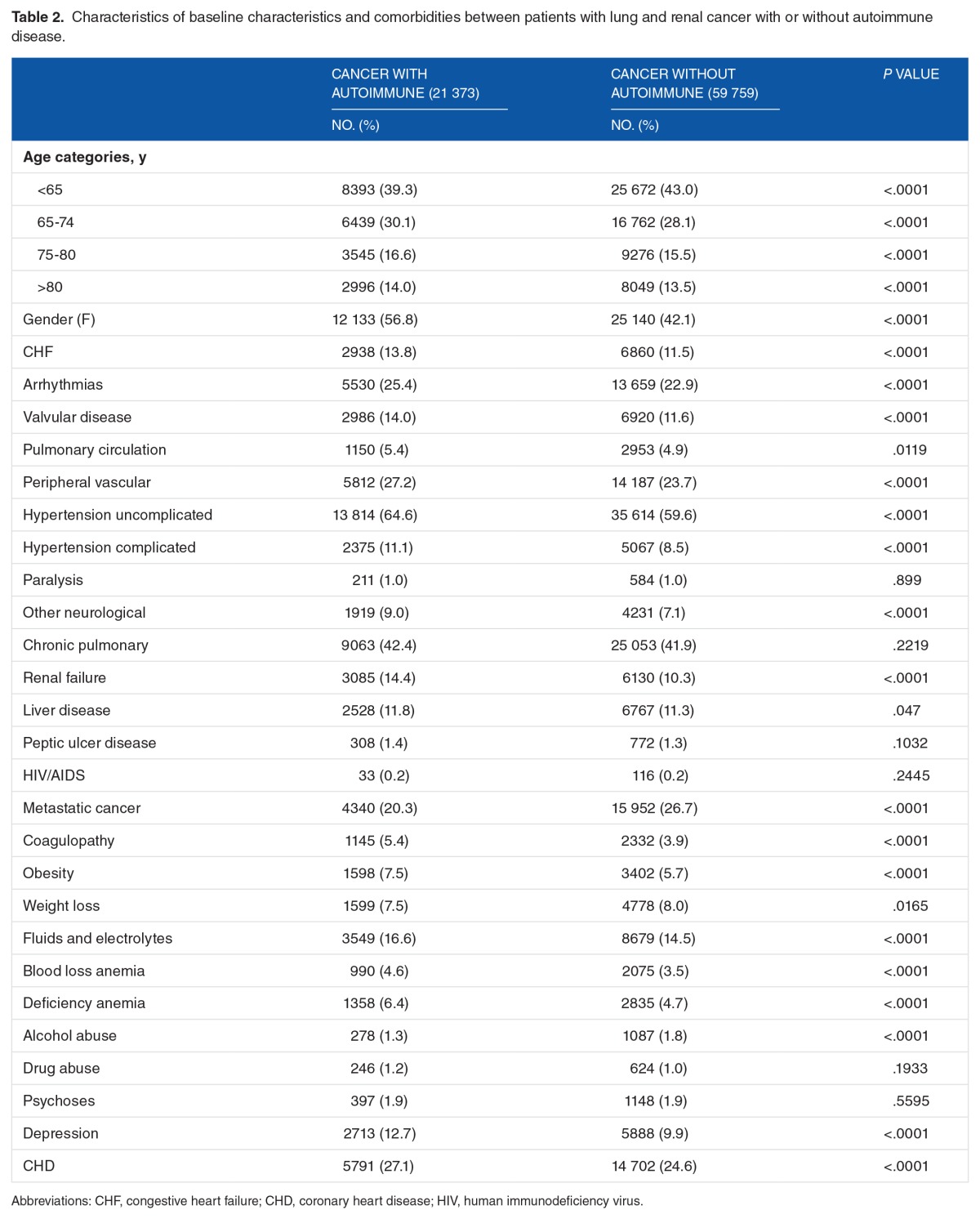

We identified 53 783 patients with lung cancer and 27 349 patients with renal cancer of whom 13 156 (24.5%) and 8217 (30.1%) also had an autoimmune disease, respectively. Hypothyroidism (55.8%, 56.7%), rheumatoid arthritis (20.2%, 18.1%), and type 1 diabetes mellitus (11.5%, 14.5%) were the most common for patients with both lung and renal cancers, respectively (Table 1). Baseline characteristics and comorbidities are listed in Table 2. Patients with cancer with autoimmune disease were more likely to be women, older, and had higher prevalence of comorbidities than patients with cancer without autoimmune disease (Table 2).

Table 1.

Autoimmune disorders in patients with lung and renal cancer between the years 2009 and 2013.

Table 2.

Characteristics of baseline characteristics and comorbidities between patients with lung and renal cancer with or without autoimmune disease.

More than a quarter of patients diagnosed with lung and renal cancer were found to have a comorbid autoimmune condition. When considering that immune checkpoint inhibition is only approved in late stages of cancer, it is not clear whether the benefits of pursuing treatment in patients with autoimmune disease outweigh the risk of inducing worse irAEs. Several case reports have been published showing that while discontinuation of the ICI results in resolution of the irAE, long courses of medications specific to the autoimmune reaction may be needed to mitigate the effects of ICI therapy.11–13 In a large systematic review of 251 cases involving anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 agents, approximately 52% of treated patients discontinued ICI therapy due to the irAEs.11 Less than 10% required no treatment for the irAE, whereas the remainder was treated with corticosteroids, infliximab (an anti-tumor necrosis factor agent), or disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Death due to the irAEs occurred in 4.7% of patients. Cutaneous autoimmune reactions are commonly associated with ICI therapy, but a case report on 2 patients with metastatic melanoma illustrated that irAEs may not appear until long after initiation of therapy.13 An autopsy study presented an elderly patient with melanoma exhibiting a systemic inflammatory response that affected multiple organ sites ultimately resulting in the death of the patient.14

Limitations

This study is subject to the limitations of all claims-based studies.15,16 Notably, claims data lack detailed information on laboratory values or information on tumor staging, which may have influenced the outcomes of this study. This study was limited to a 1-year follow-up due to the availability of data and the heterogeneity and variation of time confounded with longer follow-up. This study is strengthened by a large sample size and the inclusion of both commercial and Medicare claims.

Conclusions

The exclusion of patients with autoimmune conditions from the approval studies of nivolumab and pembrolizumab resulted in a lack of clinical guidance for a large population of patients that oncologists must decide whether to treat or not. In late-stage treatment of these cancers, the potential durable response associated with ICIs will need to be weighed against the worsening of the patient’s autoimmune condition, a decision for which clinical trials have not provided a concrete answer. Future evaluation of real-world treatment patterns will be needed to assess ICI usage and response in patients with autoimmune conditions.

Footnotes

PEER REVIEW: Six peer reviewers contributed to the peer review report. Reviewers’ reports totaled 827 words, excluding any confidential comments to the academic editor.

FUNDING: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The project described was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant UL1TR001998-01. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the work. SMEl-R and JDB conducted the data collection, analysis and interpretation. SMEl-R drafted the article and final approval was received by all authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Taube JM, Anders RA, Young GD, et al. Colocalization of inflammatory response with B7-h1 expression in human melanocytic lesions supports an adaptive resistance mechanism of immune escape. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:127ra137. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bristol-Myers Squibb . Opdivo (Nivolumab) Prescribing Information. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brahmer JR, Drake CG, Wollner I, et al. Phase I study of single-agent anti-programmed death-1 (MDX-1106) in refractory solid tumors: safety, clinical activity, pharmacodynamics, and immunologic correlates. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3167–3175. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lipson EJ, Forde PM, Hammers HJ, Emens LA, Taube JM, Topalian SL. Antagonists of PD-1 and PD-L1 in cancer treatment. Semin Oncol. 2015;42:587–600. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2015.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merck & Co . Keytruda (Pembrolizumab) Prescribing Information. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co.; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rizvi NA, Mazieres J, Planchard D, et al. Activity and safety of nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, for patients with advanced, refractory squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 063): a phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:257–265. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70054-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kong YC, Flynn JC. Opportunistic autoimmune disorders potentiated by immune-checkpoint inhibitors anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1. Front Immunol. 2014;5:206. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan SA, Pruitt SL, Xuan L, Gerber DE. Prevalence of autoimmune disease among patients with lung cancer: implications for immunotherapy treatment options. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:1507–1508. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdel-Wahab N, Shah M, Suarez-Almazor ME. Adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade in patients with cancer: a systematic review of case reports. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0160221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibson R, Delaune J, Szady A, Markham M. Suspected autoimmune myocardi-tis and cardiac conduction abnormalities with nivolumab therapy for non-small cell lung cancer. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:bcr2016216228. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-216228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mochel MC, Ming ME, Imadojemu S, et al. Cutaneous autoimmune effects in the setting of therapeutic immune checkpoint inhibition for metastatic melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:787–791. doi: 10.1111/cup.12735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koelzer VH, Rothschild SI, Zihler D, et al. Systemic inflammation in a melanoma patient treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors-an autopsy study. J Immunother Cancer. 2016;4:13. doi: 10.1186/s40425-016-0117-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneeweiss S, Avorn J. A review of uses of health care utilization databases for epidemiologic research on therapeutics. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:323–337. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhan C, Miller MR. Administrative data based patient safety research: a critical review. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12:ii58–ii63. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.suppl_2.ii58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]