Abstract

The Queensland preventive health survey is conducted annually to monitor the prevalence of behavioural risk factors in the north-east Australian state. Prompted by domestic and international trends in mobile telephone usage, the 2015 survey incorporated both mobile and landline telephone numbers from a list-based sampling frame. Estimates for landline-accessible and mobile-only respondents are compared to assess potential bias in landline-only surveys in the context of public health surveillance. Significant differences were found in subcategories of all health prevalence estimates considered (alcohol consumption, body mass index, smoking, and physical activity) from 2015 survey results. Results from Australian and international studies that have considered mobile telephone non-coverage bias are also summarised and discussed. We find that adjusting for sampling biases of telephone surveys by weighting does not fully compensate for the differences in prevalence estimates. However, predicted trends from previous years' surveys only differ significantly for the 2015 prevalence estimates of alcohol consumption. We conclude that the inclusion of mobile telephones into standard telephones surveys is important for obtaining valid, reliable and representative data to reduce bias in health prevalence estimates. Importantly, unlike some international experiences, the addition of mobiles telephones into the Queensland preventive health survey occurred before population trends were significantly affected.

Keywords: Health prevalence estimates, Non-coverage bias, Dual-frame survey, Public health surveillance, Telephone surveys

Highlights

-

•

There is a rapidly growing proportion of adults who are contactable via mobile-only.

-

•

Exclusion of mobile-only group leads to biases in health prevalence estimates.

-

•

Weighting and controlling for age differences does not correct for these biases.

-

•

A list-based survey yields representative statistics for public health policy.

1. Introduction

Telephone surveys continue to be one of the most cost-effective mechanisms to collect general population health information (Barr et al., 2012, Blumberg and Luke, 2007, Dal Grande and Taylor, 2010, Mokdad, 2009). These surveys provide data critical for health surveillance (Dal Grande and Taylor, 2010), informing public health policy (Mokdad, 2009), and promoting healthy lifestyle strategies (Campostrini et al., 2011). Sampling frame completeness and the degree to which it represents the population greatly impacts on the accuracy of results, especially for public health surveys that are used to assess or inform preventative medicine (Galesic et al., 2006).

Broadly, there are two approaches to sampling telephone numbers: random generation from known telephone exchanges (random-digit dialling, RDD) or randomly selecting telephone numbers sourced from lists such as directories or administrative sources (list-based sampling). List-based frames include an RDD component to capture unlisted numbers (Groves, 1990). RDD sampling has been commonplace in the USA since the 1980s (Massey, 1988), whereas in Australia, the Electronic White Pages (EWP), a list of landline telephones produced by the national telecommunications provider (Telstra), was commonly used as a sampling frame (Taylor and Dal Grande, 2008). The EWP provided a reliable and comprehensive listing of residential telephone numbers and was more efficient than RDD frames which generate a low proportion of eligible numbers due to the distribution of the Australian population (Wilson et al. 1999). In 2004, after legal proceedings over copyright, the EWP was commercialised and sampling costs to survey providers increased (Fitzgerald and Bartlett, 2003). RDD then became the more commonly used sampling approach.

While most households in the 1980s included a landline telephone number, by the mid-2000s the number had declined rapidly due to uptake of mobile telephones (Lee et al., 2010). In 2014, 29% of Australian adults were estimated to be mobile-only telephone users (mobile-only), a doubling since 2010 (ACMA, 2015). Comparatively, 47.4% of US households were mobile-only in 2014 (Blumberg and Luke, 2015a) and in many European countries, mobile-only households outnumbered those with a landline telephone (Mohorko et al., 2013). Failing to include the mobile-only sub-population in sampling frames may adversely impact population health estimates due to over- and under-representation. Of particular concern, is under-representation of vulnerable groups including young people and low-income households (Blumberg and Luke, 2007, Blumberg and Luke, 2009, Keeter et al., 2007, Liu et al., 2011), likely due to increasing percentage of mobile-only households (Keeter et al., 2007), under-coverage (Lee et al., 2010), and declining response rates (Keeter et al., 2006). Telephone survey methodology has therefore undergone substantial changes to address these challenges. To-date, the two most common techniques are (a) modifying the telephone sampling frame to include both landline and mobile telephone numbers, or (b) enhancing the weighting strategy for landline RDD surveys to adjust for reduced representativeness (see Battaglia et al. (2008) for example).

Dual-frame sampling includes landline and mobile numbers by combining a randomly generated list of landline telephone numbers with an independently generated random list of mobile telephone numbers. This is not straight-forward and the international experience has been mixed (Brick, 2011, Mohorko et al., 2013). While there is general agreement that non-coverage bias is reduced through inclusion of the mobile-only population (Blumberg and Luke, 2009, Mohorko et al., 2013), possible duplication of survey participants using both landline and mobile telephones (dual-users) adds complexity. This overlap is addressed through weighting strategies (Hartley, 1974), however, there is no agreed consensus as to the optimal estimator (Arcos et al., 2015). Furthermore, the choice of estimator is influenced by the type of information available about the mobile telephone population.

Non-coverage bias from the exclusion of a mobile-only frame has been investigated by several US and Australia health surveys. The US Behavioural Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) and National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) are two key ongoing national health surveillance surveys that collect information on telephone usage. Australian surveys with this capacity include the Australian National Health Survey (NHS), the Social Research Centre Dual-frame Omnibus Survey (SRCDOS), the New South Wales Population Health Survey (NSWPHS), the South Australia Health Omnibus Survey (SAHOS) and the South Australian Monitoring and Surveillance System (SAMSS). These Australian surveys differ in terms of mode of data collection (face-to-face versus telephone), sampling frame (dual-frame RDD versus a multi-stage geographically-based household selection) and survey area (national versus state-based) (see Table 1). A trait that several of these studies share, however, is that they are serial cross-sectional surveys used to monitor trends in health behaviours over time. Understanding potential non-coverage bias, differential non-response bias, and impacts to our interpretation of changes in population-level risk factor prevalence, is of primary interest for these surveys.

Table 1.

Significant differences in the prevalence of health indicators for mobile-only and landline-accessible populations from selected studies†.

| Study details | US | Australia | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Publication | Link et al. (2007) | Hu et al. (2011) | Blumberg and Luke (2015b) | Blumberg and Luke (2015a) | Dal Grande and Taylor (2010) | Livingston et al. (2013) | Barr et al. (2014) | Baffour et al. (2016a) |

| Survey Year | 2007 | 2008 | 2014 | 2015 | 2008a | 2011 | 2012 | 2012 |

| Region | GA, NM, PA | 18 States | National | National | SA | National | NSW | National |

| Interview | Telephone | Telephone | Face-to-face | Face-to-face | Face-to-face | Telephone | Telephone | Face-to-face |

| Data source | BRFSS Study | BRFSS Study | NHIS | NHIS | SAHOS | SRCDOS | NSWPHS | NHS |

| Respondents | 1164 | 171,033 | 17,668 | 17,191 | 2816 | 2014 | 15,214 | 15,565 |

| Notes | Mobile sampleb | Magnitude unavailablec | Unweighted resultsd | Reconstructede | ||||

| Difference in health indicator prevalence between mobile-only and landline-accessible populations (mobile-only minus landline-accessible estimate) | ||||||||

| Normal weight | More likely | |||||||

| Overweight | Less likely | − 11.3%f | − 9.4%f | |||||

| Obese | Not sig. | − 2.2% | Not sig. | Not sig. | Not sig. | − 11.3%f | − 9.4%f | |

| Current smoker | Not sig. | 12.1% | 7.5% | 7.2% | More likely | 8.0% | 14.3% | 13.5% |

| Excessive drinking | 13.2% | 13.8% | 10.7% | 11.2% | Not sig. | + 10.3%g | + 21.9%h | |

| Physical activity | Not sig. | 4.1% | 6.3% | 5.6% | 13.5% | 6.2% | ||

Weighted results are presented, unless otherwise stated, which adjust the survey results to known population benchmarks. All results listed are significant at the 95% level. Blank cells indicate that corresponding estimates were not considered/reported by the authors. See Table A1 for health definitions from each paper. Contractions used: SAHOS - South Australian Health Omnibus Survey, NSWPHS - New South Wales Population Health Survey, NHS - National Health Survey, SRCDOS - Social Research Centre Dual-frame Omnibus Survey, BRFSS - Behavioural Risk Factor Surveillance System, NHIS - National Health Interview Survey, SA. – South Australia, NSW – New South Wales, GA – Georgia (US), NM. - New Mexico (US), PA - Pennsylvania (US), Not sig. – Not significant.

A positive difference indicates the mobile-only population had a higher estimate than the landline-accessible population.

We report the most recent compatible survey results from the SAHOS.

The relevant significance test in Link et al. (2007) tested the difference between mobile-only and dual users from the mobile sample, this is reported here.

The significant differences were indicated on page 4 of Dal Grande and Taylor (2010) along with estimates for the mobile-only population, but not the landline population. Hence the point estimate of the difference was not able to be reconstructed. Only significant differences from 2006 to 2008 were reported, but the SAHOS was also conducted in 1999 and 2004.

In Livingston et al. (2013) weighted prevalence estimates for the mobile-only sample were not provided, the difference in the mobile sample and the landline sample are reported.

Differences reconstructed from relative differences on page 5 Barr et al. (2014).

Overweight and obese categories were combined in these studies and are listed twice here.

Definition (vi) reported here but definition (vii) was also significant (+ 9.4%), see Table A1.

Definition (iv) reported here but definition (v) was also significant (+ 19.0%), see Table A1.

The aforementioned US and Australian surveys show strong evidence of heterogeneity between mobile-only respondents and those contactable by landline for the reported health risk factors (smoking, alcohol consumption, obesity and physical activity). The estimated differences are also presented in Table 1. Surveys with the larger sample sizes (NSWPHS, NHS, and BRFSS) all reported significant differences. Furthermore, the face-to-face surveys that do not rely on telephone-based sampling (SAHOS, NHS, and NHIS) were better able to detect differences between the landline and mobile-only subpopulations. Recently, in South Australia, Dal Grande et al. (2016) found mixed evidence of health prevalence estimate differences between the landline-accessible and mobile-only populations.

Weighting strategies can address bias in landline-based telephone surveys. This weighting adjusts the sample to match the socio-demographic composition of the population, but there is potential non-coverage bias due to the exclusion of the mobile-only subpopulation, especially if this group is not uniformly distributed in the population (Blumberg and Luke, 2007). In Australia, weighting landline telephone respondents using the Australian Census of Population and Housing data has corrected for bias in prevalence estimates in several studies (Dal Grande et al., 2015, Dal Grande and Taylor, 2010, Wilson et al., 1999). In particular, Dal Grande et al. (2015) used a raking methodology to weight estimates and reduce bias from the SAMSS survey which resulted in estimates comparable to those from the 2011 census for South Australia. The authors found that raking outperformed traditional post-stratification weighting methods for estimating several health indicators as assessed by comparing their estimates to those obtained from the 2013 SAHOS and the 2011–12 South Australian sub-sample from the Australian NHS. In contrast, Baffour et al. (2016a) demonstrated significant prevalence estimate bias for being obese or overweight, smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical exercise using post-stratification weighting and data from the Australian NHS. Contradictory findings may be due to differences in bias between telephone and face-to-face surveys (Baffour et al., 2016a), indicating potential problems in using telephone surveys to assess non-coverage bias. The list-based frame used in the current study provides an assessment of non-coverage bias that results from excluding the mobile only population from the sample without relying on an RDD sample.

Assessing trends in key health indicators is a primary aim of ongoing population health monitoring. Nationally, in Australia, such surveys are typically conducted using face-to-face interview or by respondents self-completing hand-delivered surveys (ABS, 2015, AIHW, 2017). At the state level, data are predominantly collected by telephone (Barr et al., 2014, Clemens et al., 2014, DHHS, 2015, Tomlin et al., 2016). Whilst the importance of state-wide surveys to national statistical infrastructure is recognised, inclusion of mobile telephones in these surveys has been slow due to the lack of geographical identifiers for Australian mobile telephone numbers (Dal Grande et al., 2015), and prohibitive costs due to screening numbers from unwanted states and territories. Despite this challenge, New South Wales (NSW), Victoria and Queensland have recently transitioned to frames that include both mobile and landline telephone numbers. In NSW and Victoria, overlapping dual-frame designs were used. In Queensland, a list-based sampling frame that included both mobile and landline telephone numbers, unique among Australian states and territories (QGSO, 2015), was used.

Differences in mobile-only compared to landline-only or dual-phone respondents have been demonstrated in several Australian surveys (Barr et al., 2012, Jackson et al., 2014, Livingston et al., 2013). To date, all surveys have used dual frame sampling, which means that differences in mobile-only respondents may be due in part to differences in the samples. For example, differences in dual-phone respondents sampled from a landline frame and a mobile frame have been reported even when results are age-adjusted (Barr et al., 2015, Barr et al., 2014). Other alternative approaches such as face-to-face surveys, multi-modal surveys and online based surveys are available, but these are either expensive or currently in their infancy.

The extent to which inclusion of mobile telephones impacts trends, however, is much less established. In Australia, this has only been investigated using one state-wide survey which employed dual-frame sampling (Barr et al. 2012).. Significant differences in smoking and obesity trends using the landline-only frame compared to the dual-frame were observed, but it was difficult to truly establish how much this was a consequence of the methodology or the risk population (Barr et al. 2015). Given the significant investment in annual health monitoring at the state level and the importance of trend analysis to develop evidence-based programs and policy, it is important to quantify the extent to which trends are impacted by changes to sampling methodology.

The current study used a list-based sampling frame to assess these impacts, which removed the additional complication of dual-frame weighting and separates the effects of non-coverage and non-response bias. Specifically, the Queensland preventive health telephone survey was used to (a) quantify bias by comparing mobile-only to landline-accessible participants, and (b) assess whether the inclusion of mobile telephones significantly impacted time series trends across a 13-year period.

2. Methods

2.1. Dataset

The Queensland Government Department of Health (Queensland Health) conducts a preventive health telephone survey annually (the survey). Comparable data for smoking, obesity, and physical activity are available for 2002 (smoking only), 2004, 2006, and annually from 2008. Comparable data for alcohol consumption were collected annually since 2010. The survey sampling frame was a list-based telephone frame from 2002 to 2008 and a landline RDD sampling frame from 2009 to 2014. To include mobile telephone numbers, the sampling frame reverted to a list-based frame maintained by the Queensland Government Statistician's Office (QGSO) in 2015. Under the authority of the Statistical Returns Act 1896, QGSO maintains and uses a sampling frame of Queensland private dwellings assembled for official statistical purposes. For each dwelling the frame holds associated telephone numbers that are either a landline, one or more mobile numbers owned by residents in the dwelling, or both. This sampling frame provides near-complete coverage of the Queensland resident population.

The sampling design includes a geographic stratification, typically local government area (LGA), the lowest tier of Australian government. Households were randomly selected from each area with probability proportional to the population distribution over the LGA. An oversample was applied to less populous areas. All telephone numbers associated with a selected dwelling were tried and upon contact, a participant was randomly selected from those aged 18 years or over who resided in the household. Randomisation occurred regardless of whether contact was made on a mobile or landline telephone number. The response rate was 65%. To classify respondents as ‘landline-accessible’ or ‘mobile-only’, mobile telephone contacts were asked if they also had a landline telephone number and landline-contacted participants were asked if they used a personal or work mobile phone. From this, respondents were classified into ‘landline-accessible’ or ‘mobile-only’.

Investigation focused on measures of smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity and obesity. The graduated-quantity-frequency method (Dawson, 2003) measured alcohol use with an average of two or more alcoholic drinks consumed daily categorised as ‘lifetime risky drinkers’ (NHMRC, 2009). Daily smoking was assessed by current smoking status using the criteria that the respondent had smoked 100 cigarettes over their lifetime, consistent with Australian standards (see AIHW (2011), for example). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as respondents' reported weight (in kilograms) divided by their height (in metres) squared then categorised as (i) underweight (BMI < 18.50), (ii) healthy weight (BMI = 18.50–24.99), (iii) overweight (BMI = 25.00–29.99), and (iv), or obese (BMI ≥ 30). The Active Australia instrument (Brown et al., 2008) measured physical activity with sufficient physical activity defined as (at least) 150 min of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity on five separate occasions in the past week.

Sociodemographic variables used in the analysis included respondent sex, age and geographic region. Region was based on residential address as specified in the sampling frame with residential postcode confirmed at the time of interview. The postcode varied from the sampling frame for 10.3% of respondents and was corrected at the time of interview.

2.2. Statistical weighting

The statistical weights were computed over a series of steps. First, the design weight takes into account the stratified sampling design and the different chances of inclusion due to the number of adults within the household. The second weight is the post-stratification adjustment for nonresponse and oversampling. This adjusts the observed sample distribution of the survey responses to correspond to a set of known population benchmark characteristics, specifically age, sex, and geographic location using the Australian Bureau of Statistics Queensland estimated resident population. Weighting was applied using a generalised regression weighting algorithm, with auxiliary variables to (a) calibrate the sample to compensate for non-response bias, and (b) reduce the variance of an outcome measure (Bell, 2000, Deville et al., 1993). These weighting adjustments were used because they were simple and provided consistent representative results. Additional auxiliary variables, such as employment, education and length of residence are known to be associated with non-response (Baffour et al., 2016a, Dal Grande et al., 2015) but due to data availability were not considered.

2.3. Analysis

Prevalence estimates and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated for the total sample, the landline-accessible sample, and the mobile-only sample. Weighted and unweighted prevalence estimates were used to investigate the degree to which weighting compensated for differential non-response by telephone status, which may vary by age profile between landline-accessible and mobile-only populations (Baffour et al., 2016a). To investigate the effects of differences in the demographic profile between these subgroups, weighted and unweighted estimates were age adjusted using logistic regression.

The impact on historical trends due to mobile telephone inclusion was also investigated. Using trends from 2004 to 2014 (or 2010 to 2014 for alcohol consumption) data, a predicted 2015 estimate was calculated. This predicted 2015 estimate was then compared to the actual 2015 result. When the actual 2015 result fell outside the 95% CI of the predicted 2015 result, it was considered off-trend from the historical prevalence estimates.

Whether the overall trend was significantly different due to the inclusion of mobile telephones in 2015 was investigated by calculating trends using (a) the entire 2015 sample and (b) the landline-accessible subsample. Statistical significance was assessed by model-based estimation using Poisson regression analysis (Frome and Checkoway, 1985). All analyses were conducted using Stata statistical software, version 13 (StataCorp, 2015).

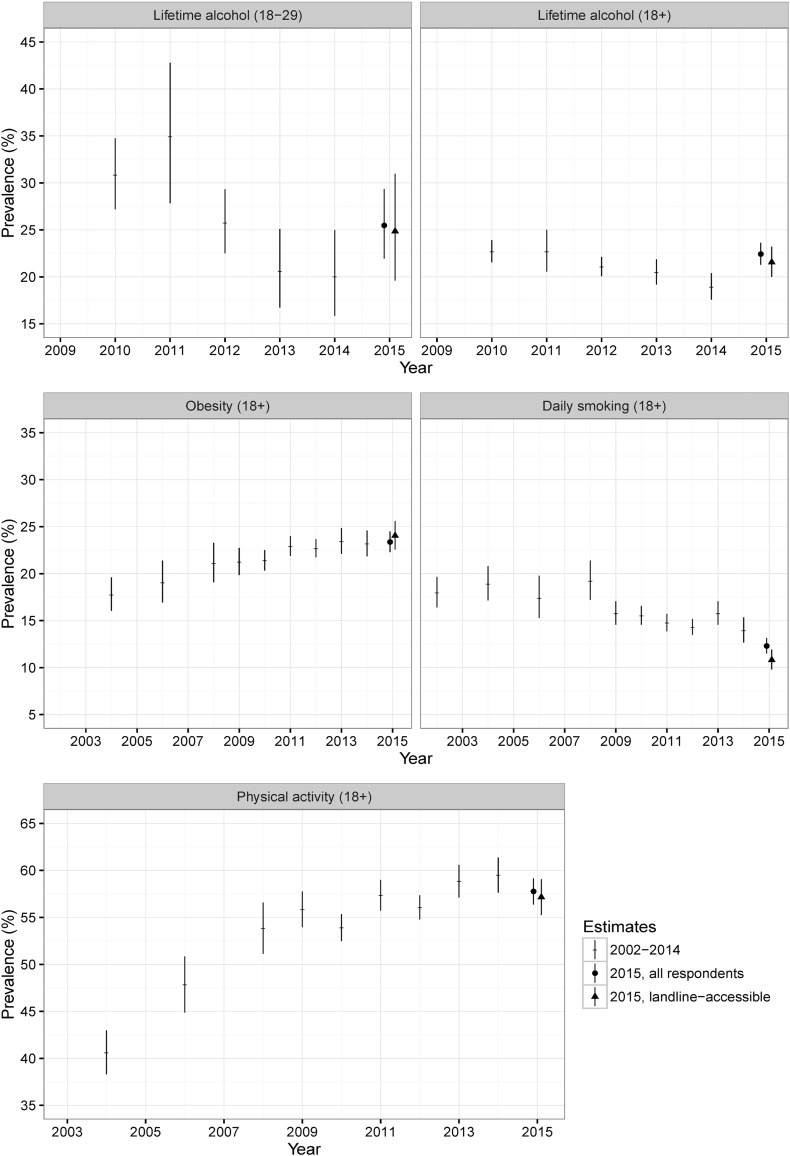

3. Results

Table 2 shows weighted and unweighted age, sex, and telephone status population estimates from the 2015 survey. For the entire sample weighted age and sex estimates were comparable to the 2011 Australian Census population estimates for Queensland. The weighted prevalence of mobile-only respondents was 29.6% (the unweighted figure is 27.4%), and is comparable to the national estimates from the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA, 2015). Of the adult Queensland population, 22.4% were engaged in lifetime risky alcohol consumption, 57.7% were overweight or obese, 12.3% were daily smokers and 42.5% were sedentary or had insufficient physical activity in 2015. The prevalence estimates and associated 95% confidence intervals are presented in Fig. 1, showing their change over time and possible impact of introducing mobile telephones.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic and risk factor prevalence by telephone status among Queensland adults, 2015.

| Total sample (12,568) |

Landline-accessible (n = 9119) |

Mobile-only (n = 3449) |

Test for difference by telephone status |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted |

Unweighted |

Weighted |

Unweighted |

Weighted |

Unweighted |

Weighted P-value |

Unweighted P-value |

|||||||||

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | Un-adjusted | Age adjusted | Un-adjusted | Age adjusted | |

| Persons | 100 | 100 | 70.4 | 69.1, 71.7 | 72.6 | 71.8, 73.3 | 29.6 | 28.3, 30.9 | 27.4 | 26.7, 28.2 | ||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||||||||

| Male | 49.4 | 48.1, 50.8 | 43.9 | 43.0, 44.8 | 48.2 | 46.6, 49.8 | 41.9 | 40.9, 42.9 | 52.4 | 49.7, 55.0 | 49.3 | 47.6, 51.0 | 0.009 | 0.02 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Female | 50.6 | 49.2, 52.0 | 56.1 | 55.2, 57.0 | 51.8 | 50.2, 53.4 | 58.1 | 57.1, 59.1 | 47.6 | 45.0, 50.3 | 50.7 | 49.0, 52.4 | ||||

| Age categories | ||||||||||||||||

| 18–24 years | 10.8 | 9.6, 12.1 | 4.1 | 3.8, 4.5 | 9.2 | 7.9, 10.8 | 2.9 | 2.5, 3.2 | 14.5 | 12.2, 17.1 | 7.5 | 6.6, 8.4 | < 0.001 | – | < 0.001 | – |

| 25–34 years | 19.8 | 18.6, 21.1 | 11.9 | 11.3, 12.4 | 12.7 | 11.4, 14.1 | 7.3 | 6.7, 7.8 | 36.9 | 34.2, 39.6 | 24.0 | 22.6, 25.4 | < 0.001 | – | < 0.001 | – |

| 35–44 years | 19.3 | 18.3, 20.4 | 15.7 | 15.0, 16.3 | 18.8 | 17.6, 20.1 | 14.2 | 13.5, 14.9 | 20.6 | 18.8, 22.6 | 19.6 | 18.3, 20.9 | 0.115 | – | < 0.001 | – |

| 45–54 years | 15.3 | 14.5, 16.2 | 17.6 | 16.9, 18.3 | 16.8 | 15.8, 17.9 | 17.2 | 16.4, 18.0 | 11.7 | 10.5, 13.0 | 18.6 | 17.3, 20.0 | < 0.001 | – | 0.064 | – |

| 55–64 years | 16.9 | 16.0, 17.8 | 20.7 | 20.0, 21.4 | 19.5 | 18.4,20.6 | 21.8 | 20.9, 22.7 | 10.8 | 9.6, 12.1 | 17.9 | 16.6, 19.2 | < 0.001 | – | < 0.001 | – |

| 65–74 years | 11.7 | 11.1, 12.4 | 19.0 | 18.4, 19.7 | 14.6 | 13.8, 15.5 | 22.3 | 21.4, 23.1 | 4.8 | 4.2, 5.5 | 10.5 | 9.5, 11.6 | < 0.001 | – | < 0.001 | – |

| 75 + years | 6.2 | 5.7, 6.6 | 11.0 | 10.5, 11.6 | 8.4 | 7.8, 9.0 | 14.4 | 13.7, 15.2 | 0.8 | 0.6, 1.2 | 2.0 | 1.5, 2.5 | < 0.001 | – | < 0.001 | – |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||||||||||||||

| Abstainers | 17.5 | 16.6, 18.5 | 21.4 | 20.7, 22.2 | 19.2 | 18.0, 20.4 | 23.1 | 22.2, 24.0 | 13.7 | 12.1, 15.3 | 17.1 | 15.8, 18.4 | < 0.001 | 0.014 | < 0.001 | 0.042 |

| Low risk drinking | 60.0 | 58.7, 61.4 | 56.9 | 56.0, 57.7 | 60.0 | 58.4, 61.5 | 57.6 | 56.6, 58.6 | 60.1 | 57.5, 62.7 | 54.9 | 53.3, 56.6 | 0.921 | 0.478 | 0.008 | < 0.001 |

| High risk drinking 18 + | 22.4 | 21.3, 23.6 | 21.7 | 21.0, 22.5 | 20.8 | 19.5, 22.2 | 19.3 | 18.5, 20.2 | 26.2 | 23.9, 28.6 | 28.0 | 26.5, 29.0 | < 0.001 | 0.005 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| High risk drinking 18–29 | 25.5 | 22.0, 29.4 | 26.1 | 24.0,28.7 | 25.0 | 19.8,30.9 | 24.0 | 20.3, 27.9 | 26.0 | 21.3, 31.2 | 27.6 | 24.3, 31.1 | 0.793 | – | 0.154 | – |

| BMI | ||||||||||||||||

| Underweight | 2.3 | 1.9, 2.9 | 2.4 | 2.1, 2.7 | 1.9 | 1.5, 2.4 | 2.2 | 1.9, 2.5 | 3.4 | 2.4, 4.9 | 2.8 | 2.3, 3.5 | 0.006 | 0.076 | 0.04 | 0.036 |

| Healthy weight | 40.0 | 38.6, 41.4 | 35.6 | 34.7, 36.5 | 38.9 | 37.3, 40.5 | 34.7 | 33.7, 35.7 | 42.5 | 39.8, 45.3 | 37.9 | 36.2, 39.5 | 0.023 | 0.347 | 0.001 | 0.411 |

| Overweight | 34.3 | 33.0, 35.7 | 34.8 | 34.0, 35.7 | 34.6 | 33.1, 36.1 | 35.3 | 34.3, 36.3 | 33.7 | 31.1, 36.3 | 33.5 | 31.9, 35.2 | 0.529 | 0.162 | 0.07 | 0.901 |

| Obese | 23.4 | 22.3, 24.5 | 27.2 | 26.4, 28.0 | 24.6 | 23.3, 26.0 | 27.8 | 26.8, 28.7 | 20.4 | 18.5, 22.4 | 25.8 | 24.3, 27.3 | 0.001 | 0.209 | 0.026 | 0.146 |

| Smoking | ||||||||||||||||

| Daily smoking | 12.3 | 11.5,13.2 | 14.1 | 13.5, 14.8 | 10.6 | 9.7, 11.5 | 11.3 | 10.7, 12.0 | 16.5 | 14.8, 18.3 | 21.6 | 20.3, 23.0 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Not a daily smoker | 87.7 | 86.8, 88.5 | 85.9 | 85.2, 86.5 | 89.4 | 88.5, 90.3 | 88.7 | 88.0, 89.3 | 83.5 | 81.7, 85.2 | 78.4 | 77.0, 79.7 | ||||

| Physical activity | ||||||||||||||||

| Insufficient | 42.5 | 41.1, 43.9 | 46.7 | 45.8, 47.6 | 44.3 | 42.7, 46 | 48.3 | 47.2, 49.4 | 38.4 | 35.9, 40.9 | 42.9 | 41.2, 44.6 | < 0.001 | 0.147 | < 0.001 | 0.014 |

| Sufficient | 57.5 | 56.1, 58.9 | 53.3 | 52.4, 54.2 | 55.7 | 54, 57.3 | 51.7 | 50.6, 52.8 | 61.6 | 59.1, 64.1 | 57.1 | 55.4, 58.8 | ||||

Fig. 1.

Prevalence and 95% confidence intervals for landline respondents (to 2014) and for landline-accessible and total respondents (in 2015) for Queensland.

Table 2 also shows the weighted and unweighted estimates for demographic characteristics and behavioural risk factors by telephone status. Significant differences between the mobile-only and landline-accessible respondents were observed for sex and age (except in 35–44 year olds) although weighting reduced the magnitude of differences. Significant differences were also observed for most health risk factors for both weighted and unweighted results. Among Queensland adults, mobile-only respondents had a higher prevalence of lifetime risky drinking and daily smoking. Conversely, landline-accessible adults had a higher prevalence of obesity and being insufficiently physically active. However, when weighted results are age-adjusted, the differences between landline-accessible and mobile-only respondents loses significance for obesity (P < 0.001, age-adjusted P = 0.21) and insufficient physical activity (P < 0.001, age-adjusted P = 0.15). Lifetime risky drinking among 18–29 year olds did not differ by telephone status (P = 0.79).

Table 3 presents the 2015 point estimate and 95% CI predicted from the trend to 2014 and Table 4 presents the trend coefficients when using the landline-accessible subsample only or the entire 2015 sample. The impact of including or excluding the mobile-only subpopulation can be assessed by comparing trends coefficients in these two tables. From Table 3, the actual 2015 point estimates for daily smoking, physical activity and obesity do not differ from those predicted from historical trends. For alcohol consumption, the actual 2015 estimates for adults and adults aged 18–29 both fall outside of the 95% CIs of the 2015 predicted estimates. However, Table 4 shows that when coefficients for the overall trend are compared, there is no difference in trend between the landline-accessible subsample and the total sample for any health risk factor, and specifically the coefficients for adult alcohol consumption was non-significant.

Table 3.

Comparison of predicted and actual 2015 data points using Poisson regression estimation for Queensland.

| Risk factor | Trend equation (to 2014): y = exp.(α + β1t + β2t2) | Predicted 2015 estimate using trend to 2014 | Actual 2015 result | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | β1 | β2 | Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | |

| Alcohol consumption (18 +)a | − 1.555 | − 0.045 | – | 18.4 | 17.0, 19.8 | 22.4b |

| Alcohol consumption (18–29)a | − 1.373 | − 0.129 | – | 17.2 | 13.3,21.1 | 25.5b |

| Smoking | − 1.776 | − 0.023 | − 0.001 | 13.5 | 12.1,14.8 | 12.3 |

| Obesity | − 1.609 | 0.036 | − 0.002 | 23.6 | 21.7,25.5 | 23.4 |

| Physical activity | − 0.707 | 0.044 | − 0.003 | 57.2 | 54.0,60.5 | 57.5 |

Quadratic term not included.

Actual estimate falls outside predicted 95% confidence interval.

Table 4.

Trend comparisons for selected risk factors comparing the landline-accessible respondents in Queensland and the total sample in 2015.

| Risk factor | Trend equation to 2015 landline-accessible: y = exp.(α + β1t + β2t2) |

Trend equation to 2015 total sample: y = exp.(α + β1t + β2t2) |

Difference in trend | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | β1 | β2 | α | β1 | β2 | P-value | |

| Alcohol consumption (18 +)ab⁎ | − 1.542 | − 0.028* | – | − 1.531 | − 0.013* | – | 0.192 |

| Alcohol consumption (18–29)a | − 1.337 | − 0.092 | – | − 1.314 | − 0.067 | – | 0.461 |

| Smoking | − 1.736 | − 0.023 | − 0.003 | − 1.758 | − 0.023 | − 0.002 | 0.329 |

| Obesity | − 1.614 | 0.034 | − 0.001 | − 1.608 | 0.036 | − 0.002 | 0.684 |

| Physical activity | − 0.704 | 0.045 | − 0.004 | − 0.708 | 0.044 | − 0.003 | 0.748 |

Quadratic term not included.

Significant decrease for landline only sample; non-significant decrease for the entire 2015 sample.

4. Discussion

As in other investigations, the current study demonstrated differences between mobile-only and landline-accessible respondents for smoking (Barr et al., 2012, Livingston et al., 2013) alcohol consumption (Barr et al., 2012, Jackson et al., 2014), physical activity, and obesity (Barr et al., 2012). Overall, smaller relative differences between mobile-only and landline-accessible respondents were observed in our survey. This may be attributable to a higher proportion of mobile-only households (estimated at 20% in 2012 but 29% in 2015) leading to a mobile-only population that is becoming more heterogeneous and similar to the overall population; parallel trends have been reported in the US (Blumberg and Luke, 2015a, Blumberg and Luke, 2015b, Blumberg and Luke, 2016).

Consistent with other research, the current study showed significant differences in annual prevalence of health indicators between landline-accessible and mobile-only respondents. Although an appropriate weighting adjustment to account for the sociodemographic differences reduced these differences, they remained significant after weighting. This indicates that weighting alone does not adequately compensate for non-coverage, a finding that differed from other Australian research (e.g. Dal Grande et al., 2015). This difference may be due to the geographically stratified sampling design in the current study which limited the inclusion of characteristics that influence non-response into post-stratification weights (Baffour et al., 2016b, Battaglia et al., 2008).

Similar to other studies, some differences between mobile-only and landline-accessible respondents lost significance when age-adjusted, indicating that these outcomes were associated with the difference in age profiles of the subsamples. Differences remain significant after age-adjustment for smoking and lifetime risky alcohol consumption suggesting that telephone status is independently associated with those behaviours. Similar age-adjusted results for risky alcohol consumption in NSW reported that mobile-only respondents differed from dual-telephone users from the landline only frame (Barr et al., 2014). Differences between dual-telephone respondents in the two samples used in NSW, and the resultant inability to separate the non-coverage and non-response biases, make comparisons between the results of these two studies difficult.

Outcomes associated with telephone usage independent of age are more likely to impact trends. However, the current study found that overall trends were not significantly different when the mobile-only subsample was included. This was observed even when the predicted and actual 2015 estimates differed (alcohol consumption). More specifically, a previously reported decline on overall adult alcohol consumption became non-significant and the decline in consumption among 18–29 year olds decreased. This is consistent with earlier reports that the population-level decrease in alcohol consumption is driven by 18–29 year olds while consumption among those aged 30 years and over has remained static across the time period (Department of Health, 2014). This minimal impact to trends differed from US and international research where a failure to include mobile-only households in surveys has led to significant biases in the measurement of health behaviours. This difference could be connected to the fact that only 29% of Australian adults are mobile-only (ACMA, 2015), in contrast to the US with close to 50% mobile-only households (Blumberg and Luke, 2015a).

Non-coverage bias will continue to increase for the foreseeable future due to the increasing proportion of mobile-only households. In the US, close to 90% of the adult population is contactable via mobile (Blumberg and Luke, 2016), and survey practitioners have begun redesigning RDD surveys with a single sampling frame of 100% mobile telephones. Results have shown that mobile RDD samples can be representative of the US public on a number of demographic dimensions, such as age, race and ethnicity (Jiang et al., 2015, Kennedy et al., 2016). Furthermore, mobile-only surveys provide smaller margins of error and are generally more precise than their dual-frame counterparts: the reason suggested being the reduced complexity of survey weighting when all the information is from a single frame (Kennedy et al., 2016, Peytchev and Neely, 2013). This is not currently a viable solution for Australia due to the relatively large group of landline-only users compared to the US, and poor mobile telephone reception in regional areas. It is estimated that 10.5% of the population of Queensland were in rural and remote regions (OESR, 2012). Remoteness and telephone status are linked, such that in some remote areas there will be a lack of adequate mobile coverage, leading to access only via landline telephone.

This study is subject to several limitations. First, data limitations prevented the application of more robust weighting approaches or comprehensive post-stratification methods. Second, methodological changes in time series data limit comparability between years. Given the substantial financial costs and knowledge gaps that arise while trends re-establish, the current study specifically examined the impact of non-coverage bias to inform the interpretation of overall trends rather than limit analysis to differences between subsamples within a single year of data. Third, we cannot account for the bias in mobile telephone non-response due to poor reception and other coverage factors affecting rural populations. Future work will involve incorporating information on the distribution of mobile coverage, including the relationship between poor telephone coverage of difficult-to-reach participants and the prevalence of risk factors.

4.1. Conclusion

In summary, this study found differences in health behaviours between mobile-only and landline-accessible participants using a list-based sampling frame, similar to results in studies using dual-frame sampling. Differences remained after post-stratification adjustment, supporting evidence that mobile telephone numbers should be included to obtain valid, reliable and representative data, regardless of the type of sample frame. Unlike dual-frame surveys, list-based surveys may have better coverage and do not need further weighting adjustments to account for multiple chances of inclusion in the survey (as with dual telephone users). In Queensland, it appears that the shift to include mobile-only respondents occurred before trends were significantly affected by non-coverage bias, differing from the international experience.

Ethical compliance

Ethical Clearance: In accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Ethics was obtained from the Queensland Health Central Office Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number HREC/10/QHC/49).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Funding

This study was funded by the Australian Research Council under the Linkage Funding scheme (grant number LP 130100744).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Appendix A.

Table A1.

Health definitions from publications in Table 1.

| Body weight | ||

| All papers in Table 1 | Reporteda Reported Reported. |

|

| Excessive drinkingb | ||

|

Livingston et al. (2013) Baffour et al. (2016a) |

Reported |

|

| Barr et al. (2014) | Reported |

|

|

Link et al. (2007) Hu et al. (2011) |

Reported |

|

| Blumberg and Luke, 2015a, Blumberg and Luke, 2015b | Reported |

|

| Physical activity | ||

|

Barr et al. (2014) Baffour et al. (2016a) |

Reported |

|

|

Link et al. (2007) Hu et al. (2011) |

Reported |

|

| Blumberg and Luke, 2015a, Blumberg and Luke, 2015b | Reported |

|

“Reported” denotes the result of this definition is reported in the main text of Table 1, the absent results are included in the table notes.

All standard drinks were measured or converted to Australian standard drinks.

References

- ABS, 2015 [9 March 2017]. National Health Survey: First Results, 2014–15. Explanatory Notes. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved from http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4364.0.55.001Explanatory%20Notes12014-15.

- ACMA . Australians get mobile; Australian Communications and Media Authority: 2015. 8 November 2016.http://www.acma.gov.au/theACMA/engage-blogs/engage-blogs/Research-snapshots/Australians-get-mobile Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- AIHW . Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; Canberra, ACT: 2011. 2010 National drug strategy household survey report, Drug statistics series. [Google Scholar]

- AIHW, 2017 [9 March 2017]. About the National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS). Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Retrieved from http://www.aihw.gov.au/alcohol-and-other-drugs/data-sources/about-ndshs/.

- Arcos A., del Mar Rueda M., Trujillo M., Molina D. Review of estimation methods for landline and cell phone surveys. Sociol. Methods Res. 2015;44:458–485. [Google Scholar]

- Baffour B., Haynes M., Dinsdale S., Western M., Pennay D.W. Profiling the mobile-only population in Australia: insights from the Australian National Health Survey. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health. 2016;40:443–447. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baffour B., Haynes M., Western M., Pennay D.W., Mission S., Martinez A. Weighting strategies for combining data from dual-frame telephone surveys: emerging evidence from Australia. J. Off. Stat. 2016;32:549–578. [Google Scholar]

- Barr M.L., van Ritten J.J., Steel D.G., Thackway S.V. Inclusion of mobile phone numbers into an ongoing population health survey in new South Wales, Australia: design, methods, call outcomes, costs and sample representativeness. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2012;12:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr M.L., Ferguson R.A., Steel D.G. Inclusion of mobile telephone numbers into an ongoing population health survey in new South Wales, Australia, using an overlapping dual-frame design: impact on the time series. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:517. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr M., Ferguson R., Ritten J.v., Hughes P., Steel D. Summary of the impact of the inclusion of mobile phone numbers into the NSW population health survey in 2012. AIMS Public Health. 2015;2:210–217. doi: 10.3934/publichealth.2015.2.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia M.P., Frankel M.R., Link M.W. Improving standard poststratification techniques for random-digit-dialing telephone surveys. Survey Research Methods. 2008;2:11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bell P. Research Paper: ABS Methodology Advisory Committee. Australian Bureau of Statistics; Canberra: 2000. Weighting and standard error estimation for ABS household surveys; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg S.J., Luke J.V. Coverage bias in traditional telephone surveys of low-income and young Adults. Public Opin Q. 2007;71:734–749. [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg S.J., Luke J.V. Reevaluating the need for concern regarding noncoverage bias in landline surveys. Am. J. Public Health. 2009;99:1806–1810. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.152835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg S.J., Luke J.V. National Center for Health Statistics; Atlanta, GA: 2015. Wireless Substitution: Early Release Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, January–June 2015, Early Release Reports on Wireless Substitution. [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg S.J., Luke J.V. National Center for Health Statistics; Atlanta, GA: 2015. Wireless Substitution: Early Release Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, July–December 2014, Early Release Reports on Wireless Substitution. [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg S.J., Luke J.V. National Center for Health Statistics; Atlanta, GA: 2016. Wireless Substitution: Early Release of Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, July–December 2015, Early Release Reports on Wireless Substitution. [Google Scholar]

- Brick J.M. The future of survey sampling. Public Opin Q. 2011;75:872–888. [Google Scholar]

- Brown W.J., Burton N.W., Marshall A.L., Miller Y.D. Reliability and validity of a modified self-administered version of the active Australia physical activity survey in a sample of mid-age women. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health. 2008;32:535–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2008.00305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campostrini S., McQueen V.D., Abel T. Social determinants and surveillance in the new millennium. Int J Public Health. 2011;56:357–358. doi: 10.1007/s00038-011-0263-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens S., Roselli T., Catherine Harper. Department of Health; Queensland Government, Brisbane: 2014. Trends in Preventive Health Risk Factors, Queensland 2002 to 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dal Grande E., Taylor A.W. Sampling and coverage issues of telephone surveys used for collecting health information in Australia: results from a face-to-face survey from 1999 to 2008. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2010;10:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Grande E., Chittleborough C.R., Campostrini S., Tucker G., Taylor A.W. Health estimates using survey raked-weighting techniques in an Australian population health surveillance system. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2015;182:544–556. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Grande E., Chittleborough C.R., Campostrini S., Taylor A.W. Bias of health estimates obtained from chronic disease and risk factor surveillance systems using telephone population surveys in Australia: results from a representative face-to-face survey in Australia from 2010 to 2013. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2016;16:44. doi: 10.1186/s12874-016-0145-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson D.A. Methodological issues in measuring alcohol use. Alcohol Res. Health. 2003;27:18–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health . Department of Health; Queensland Government, Brisbane: 2014. Trends in Preventive Health Risk Factors, Queensland 2002 to 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Deville J.-C., Särndal C.-E., Sautory O. Generalized raking procedures in survey sampling. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1993;88:1013–1020. [Google Scholar]

- DHHS . Victorian Population Health Survey; Department of Health and Human Services: 2015. 9 March 2017.https://www2.health.vic.gov.au/public-health/population-health-systems/health-status-of-victorians/survey-data-and-reports/victorian-population-health-survey Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald B., Bartlett C. Database protection under Australian copyright law: desktop marketing systems Pty ltd v. Telstra corporation (2002) FCAFC 112. Southern Cross Univ Law Rev. 2003;7:308–325. [Google Scholar]

- Frome E.L., Checkoway H. Use of Poisson regression models in estimating incidence rates and ratios. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1985;121:309–323. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galesic M., Tourangeau R., Couper M.P. Complementing random-digit-dial telephone surveys with other approaches to collecting sensitive data. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2006;31:437–443. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves R.M. Theories and methods of telephone surveys. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1990;16:221–240. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley H.O. Multiple frame methodology and selected applications. Sankhya. 1974;36:99–118. [Google Scholar]

- Hu S.S., Balluz L., Battaglia M.P., Frankel M.R. Improving public health surveillance using a dual-frame survey of landline and cell phone numbers. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2011;173:703–711. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A.C., Pennay D., Dowling N.A., Coles-Janess B., Christensen D.R. Improving gambling survey research using dual-frame sampling of landline and mobile phone numbers. J. Gambl. Stud. 2014;30:291–307. doi: 10.1007/s10899-012-9353-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C., Lepkowski J.M., Suzer-Gurtekin T. AAPOR; Hollywood, Florida: 2015. Transition from Landline-Cell to Cell Frame Design: Surveys of Consumers, Annual Conference of the American Association for Public Opinion Research. [Google Scholar]

- Keeter S., Kennedy C., Best J. Gauging the impact of growing nonresponse on estimates from a national RDD telephone survey. Public Opin Q. 2006;70:759–779. [Google Scholar]

- Keeter S., Kennedy C., Clark A., Tompson T., Mokrzycki M. What's missing from national landline RDD surveys?: the impact of the growing cell-only population. Public Opin Q. 2007;71:772–792. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy C., McGeeney K., Keeter S. Pew Research Center; Washington, DC: 2016. The Twilight of Landline Interviewing. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Brick J.M., Brown E.R., Grant D. Growing cell-phone population and noncoverage bias in traditional random digit dial telephone health surveys. Health Serv. Res. 2010;45:1121–1139. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01120.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link M.W., Battaglia M.P., Frankel M.R., Osborn L., Mokdad A.H. Reaching the U.S. cell phone generation: comparison of cell phone survey results with an ongoing landline telephone survey. Public Opin Q. 2007;71:814–839. [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Brotherton J.M., Shellard D., Donovan B., Saville M., Kaldor J.M. Mobile phones are a viable option for surveying young Australian women: a comparison of two telephone survey methods. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011;11:1–5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston M., Dietze P., Ferris J., Pennay D., Hayes L., Lenton S. Surveying alcohol and other drug use through telephone sampling: a comparison of landline and mobile phone samples. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013;13:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey J.T. An overview of telephone coverage. In: Groves R.M., Biemer P.P., Lyberg L.E., Massey J.T., Nicholls W.L. II, Waksberg J., editors. Telephone Survey Methodology. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1988. pp. 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Mohorko, A., de Leeuw, E., Hox, J.J., 2013. Coverage bias in European telephone surveys: developments of landline and mobile phone coverage across countries over time. Survey methods: insights from the field. Retrieved from http://surveyinsights.org/?p = 828. doi: 10.13094/SMIF-2013-00002.

- Mokdad A.H. The behavioral risk factors surveillance system: past, present, and future. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 2009;30:43–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NHMRC . Canberra; ACT: 2009. Australian Guidelines to Reduce Health Risks from Drinking Alcohol. National Health and Medical Research Council. [Google Scholar]

- OESR . Queensland Treasury and Trade; Office of Economic and Statistical Research: 2012. Population Growth Highlights and Trends, Queensland 2012.http://www.qgso.qld.gov.au/products/reports/pop-growth-highlights-trends-qld/pop-growth-highlights-trends-qld-2012.pdf 8 November 2016. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Peytchev A., Neely B. RDD telephone surveys: toward a single-frame cell-phone design. Public Opin Q. 2013;77:283–304. [Google Scholar]

- QGSO . Survey methods. Queensland Government Statistician's Office; Queensland Treasury: 2015. 8 November 2016.http://www.qgso.qld.gov.au/about-statistics/survey-methods/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp . StataCorp; College Station, TX: 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A., Dal Grande E. Chronic disease and risk factor surveillance using the SA monitoring and surveillance system (SAMSS)–history, results and future challenges. Public Health Bull S Aust. 2008;5:17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlin S., Joyce S., Radomiljac A. Department of Health; Western Australia, Perth: 2016. Health and Wellbeing of Adults in Western Australia 2015, Overview and Trends. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D.H., Starr G.J., Taylor A.W., Grande E.D. Random digit dialling and electronic white pages samples compared: demographic profiles and health estimates. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health. 1999;23:627–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.1999.tb01549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]