Abstract

Objectives:

Endoscopic approach provides excellent magnification and visualization, and a purely transnasal approach is minimally invasive method. However, it is very difficult to repair anterior and lateral fractures with the previous transnasal endoscopic approaches, since repair of orbital fractures is managed through the middle meatus and ostium from the posterior side of the nasolacrimal duct with side-viewing endoscope and curved instruments. Therefore, the authors used modified transnasal endoscopic approach as an alternative for repair of orbital floor fractures in order to effectively reach the lateral or anterior fracture of the orbital floor with straight endoscope and instruments endoscopically.

Methods:

Modified transnasal endoscopic approach through anterior space to nasolacrimal duct was performed in patients with orbital floor fracture, when patients rejected extranasal approach and reconstruction could not be performed by the previous purely transnasal endoscopic approach. After removal of the medial maxillary bone, the lateral wall of nose was shifted in the medial direction to allow wider access to the maxillary sinus. The bone fragments entrapping the orbital content are removed carefully, and correction of periorbita is performed. After surgery, patients were asked whether they have symptoms and/or complications.

Results:

This modified approach was performed in 15 patients (10 males and 5 females). Mean age at surgery was 37.6 years with a range between 17 and 67. Double vision disappeared in all patients.

Conclusions:

This novel approach appears to be a safe and effective technique for the repair of orbital floor fractures.

Keywords: Endoscopic surgery, orbital floor fracture, transnasal approach

At the time of this writing, extranasal open approaches, such as lower lid incision, and Caldwell-Luc transantral approaches, are commonly used for repair of orbital floor fractures, since extranasal open approaches gives better exposures. However, lower lid incision has some potential complications, for example, ectropion, entropion, and hypertrophic scar.1 And alloplastic implants, which may induce complications such of cyst, hematoma, inflammation, infection, abscess, and so on,2–4 are commonly used in lower lid incision. Although alloplastic implants are not used in Caldwell-Luc approach, Caldwell-Luc approach also has some potential complications, such as facial hypesthesia, oroantral fistula, dacryocystitis, gingivolabial wound dehiscence, facial swelling, numbness of teeth, and recurrent sinusitis.5,6 Also, endoscopic approach has been paid attention recently, because endoscopic approach provides excellent magnification and visualization. Soejima et al7 reported endoscopic transmaxillary repair. In this method, balloon was inserted into the maxillary sinus to support the orbital floor after window was made in the bone of the maxillary face, and connecting tube was pulled into the nasal cavity through the maxillary ostium. And a purely transnasal endoscopic approach has been reported recently,8–10 since a purely transnasal endoscopic approach is minimally invasive surgery. However, with this transnasal endoscopic method, repair of orbital fractures is managed through the middle meatus and ostium from the posterior side of the nasolacrimal duct, resulting in more difficult management with side-viewing endoscope and curved instruments. It is also difficult to repair anterior and lateral fractures through the posterior side of the nasolacrimal duct.

Hinohira et al9 advocated septoplasty and submucous conchotomy of the inferior turbinate to obtain a better view and more space for manipulation, since a purely transnasal one has limited surgical exposure. However, they reported that an extranasal procedure was used in 3 patients, and suggested that it is impossible to repair fracture using only transnasal approach, if the fracture was localized laterally in more than one-third of the orbital floor.

Recently, we reported a new method using an approach through the anterior side of the nasolacrimal duct to obtain wide and straight access to the maxillary sinus.11 With this approach, the nasolacrimal duct and the inferior turbinate can be preserved and direct access to the maxillary sinus can be achieved through the anterior side of the nasolacrimal duct. And this new approach can give better exposure of orbital floor.

We report this approach as an alternative for repair of orbital floor fractures in order to effectively reach the lateral or anterior fracture of the orbital floor endoscopically, and in order to extend the indication for purely endonasal repair of orbital floor fracture.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Surgical Method

Operations were performed to repair orbital floor fracture in patients who had both double vision and restriction in the forced duction test, or enophthalmos. The previous purely transnasal endoscopic method repair of orbital fractures was performed through the middle meatus and ostium from the posterior side of the nasolacrimal duct. And modified new approach was performed, when patients rejected extranasal approach and reconstruction could not be performed by the previous purely transnasal endoscopic approach.

The modified approach was performed based on the methodology of the modified transnasal endoscopic medial maxillectomy, which we previously reported in the resection of inverted papilloma.11 Although this modified approach is similar to the modified transnasal endoscopic medial maxillectomy, there are a few differences. An incision was made along the anterior margin of the inferior turbinate (Fig. 1A). After the lateral nasal mucosa was exfoliated, osteotomy of the medial maxillary wall was performed with conservation of the inferior turbinate and nasolacrimal duct (Figs. 1B and 2A). The exposure of only orbital floor was necessary, more dissection was not necessary like resection of inverted papilloma.11 The preserved inferior turbinate and nasolacrimal duct was shifted medially to allow wider access to the maxillary sinus (Figs. 1C-E and 2B). Dissection of the apertura piriformis and anterior maxillary wall were not necessary for repair of orbital floor fracture, although we previously reported that the dissection of the apertura piriformis and anterior maxillary wall may be performed for resection of inverted papilloma, if necessary.11

FIGURE 1.

Schema of operative procedure. (A) Incision along the anterior margin of IT. (B) Osteotomy of medial maxillary wall except ND and identification of ND and MM. (C) Entry into MS and identification of OC. (D) Schema of IT, ND, and MS. (E) ND and IT are shifted in a medial direction to allow wider access to MS. IT, inferior turbinate; MM, mucosa and periosteum of maxillary sinus; MS, maxillary sinus; ND, nasolacrimal duct; OC, ocular contents.

FIGURE 2.

During operation. (A) Identification of ND and entry to MS from anterior to IT. (B) ND and IT are shifted in a medial direction to allow wider access to MS. (C) View of orbital floor fracture with straight endoscope. (D) Identification of orbital floor fracture. (E) Placement of balloon catheter. IT, inferior turbinate; MS, maxillary sinus; ND, nasolacrimal duct.

When the ostium of maxillary sinus was occupied by the prolapsed ocular contents, which include fatty tissue and extraocular muscles such as the medial and inferior rectus muscle, the membranous portion of the medial wall of the maxillary sinus was removed to make and enlarge an opening to the maxillary sinus through the maxillary sinus following confirmation of prolapse of orbital contents into the maxillary sinus and the orbital floor fracture. The management through the maxillary sinus after confirmation of the prolapsed ocular contents is safer than that through the middle meatus before confirmation of the prolapsed ocular contents. When the ostium was not occupied by the prolapsed ocular contents, an opening was made through the middle meatus. And the membranous portion of the medial wall of the maxillary sinus was removed to enlarge an opening safely through the maxillary sinus following confirmation of prolapse of orbital contents into the maxillary sinus (Fig. 2C) and the orbital floor fracture (Fig. 2D) through the maxillary sinus. On the other hand, an opening to the maxillary sinus was made and enlarged through the middle meatus in the surgery for the resection of inverted papilloma.11

The bone fragments, which may be involved in double vision, entrapping the orbital content were removed carefully after incision in the mucosa in the maxillary sinus. The bone fragments, which may be involved in the hypesthesia of cheek, entrapping the infraorbital nerve were also removed. We removed only small bone fragments. We used large fragments for reconstruction of orbital floor. Also, the orbital tissue was pushed from the sinus into the orbita, and correction was made to the periorbita. The forced duction test was performed to confirm improvement and lack of restriction to eyeball movement after reduction of the orbital floor fracture. A ureteral balloon catheter, which is commercially available, was placed in the maxillary sinus through the middle meatus to support the orbital floor (Fig. 2E). Sterile distilled water was introduced into the balloon. After surgery, the amount of sterile distilled water was adjusted to treat enophthalmos, not to induce exophthalmos, after assessment with Hertel exophthalmometry. This balloon catheter was removed 7 to 10 days after the operation (Fig. 3A-B). The balloon catheter was removed without general or local anesthesia after removal of sterile distilled water. The method of balloon fixation was performed in accordance with the methodology previously reported.8–10 Reconstructive materials such as titanium plates or bone grafts were not used.

FIGURE 3.

Computed tomography scan results in a representative patient. (A) Computed tomography before operation. (B) Computed tomography after operation. Balloon can be seen. (C) Computed tomography after removal of balloon.

Assessment of Enophthalmos

Enophthalmos was assessed with Hertel exophthalmometry, and it was regarded as significant if 2 mm discrepancy existed.

Follow-Up

All patients have undergone follow-up clinical evaluation. At first, patients underwent follow-up at regular intervals for 2 weeks. Later, patients have undergone follow-up at interval of 1 year.

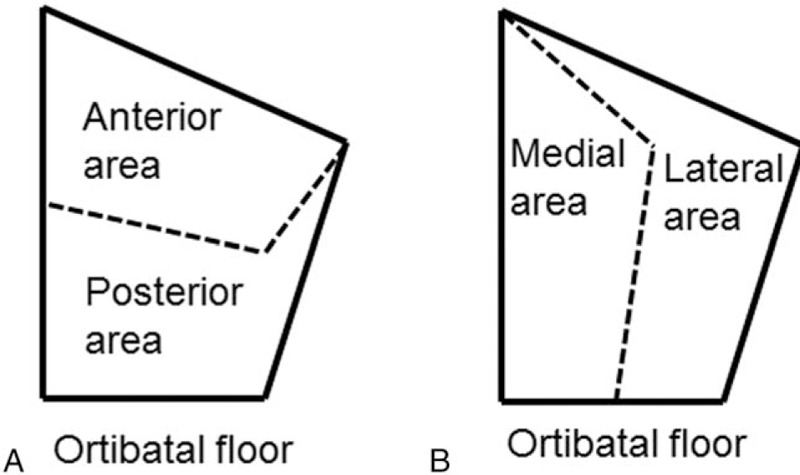

Classification of Orbital Floor Area

Orbital floor were classified into 2 areas: anterior and posterior areas. Anterior orbital floor meant former from the center, which was divided in front and behind at just same distance using sagittal computed tomography (CT). Posterior orbital floor also meant back from the center. Orbital floor were also classified into 2 areas: lateral and medial area. Lateral orbital floor meant outside the center, which was divided right and left in just same distance using coronal CT. Medial orbital floor meant inside the center (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

Classification of orbital floor area. Orbital floor was classified into 2 areas: anterior and posterior areas (A), or lateral and medical areas (B).

RESULTS

This modified transnasal endoscopic approach was performed in 15 patients with orbital floor fractures. Mean age at surgery was 37.6 years with a range between 17 and 67 (Table 1). There were 10 males and 5 females (Table 1). Five of 15 were right, and 10 were left (Table 1). Seven patients also had fractures of medial walls (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Summary of Patients’ Profile

| Location of Orbital Floor Fractures | ||||||||

| Patient | Age | Gender | Side | Medial Fracture | Anterior | Posterior | Lateral | Medial |

| 1 | 38 | M | R | + | + | + | + | + |

| 2 | 25 | M | R | + | + | + | + | + |

| 3 | 17 | F | L | + | + | + | + | + |

| 4 | 67 | F | R | − | − | + | + | + |

| 5 | 57 | F | L | + | − | + | − | + |

| 6 | 21 | M | L | − | − | + | − | + |

| 7 | 40 | F | R | − | − | + | − | + |

| 8 | 24 | M | L | − | − | + | − | + |

| 9 | 21 | M | L | − | − | + | − | + |

| 10 | 31 | M | L | − | − | + | + | + |

| 11 | 20 | M | L | − | − | + | − | + |

| 12 | 32 | M | R | + | + | − | + | + |

| 13 | 65 | M | L | + | + | + | + | + |

| 14 | 66 | F | L | − | − | + | − | + |

| 15 | 40 | M | L | + | + | + | + | + |

F, female; L, left; M, male; R, right.

During 2008 to 2015, patients underwent this novel surgery. Eighteen patients underwent subtarsal incision in this period. Twenty-five patients received transantral surgery. A purely transnasal endoscopic surgery was performed in 7 patients.

Orbital floor were classified into areas: anterior, posterior, lateral, and medial areas. Anterior orbital floor meant former from the center, which was divided in front and behind at just same distance. Posterior orbital floor also meant back from the center. Also, lateral orbital floor meant outside the center, which was divided right and left in just same distance. Medial orbital floor meant inside the center. Fractures in the anterior orbital floor were seen in 6 patients (Table 1). Fractures in the posterior area were found in 14 patients (Table 1). Eight patients had the lateral fractures, and all 15 patients had the medial fractures (Table 1).

Double vision was seen in all 15 patients. Six patients had trapdoor fractures. Nine patients had hypesthesia of the cheek. Six patients had enophthalmos (mean 3.0 mm, range 2–4 mm) preoperatively. The number of days from trauma until operation was 3 to 31 (mean days were 15.7). General anesthesia was performed in 14 patients, and local anesthesia in a patient (Table 2). Double vision disappeared in all 15 patients (Fig. 3C). The hypesthesia of the cheek in 9 patients also disappeared, although it took more than 1 year in 1 patient. Enophthalmos in 5 patients disappeared. And enophthalmos improves in 1 patient from 4 mm of discrepancy to 2 mm. Notable improvements of Hess screen test were seen in all patients. Typical preoperative and postoperative Hess screen test was shown in a representative patient (Fig. 5). Complications of exophthalmos, epiphora, facial hypesthesia, and numbness of teeth were not seen in all patients after a follow-up period of 13 to 90 months (52.9 months on average, Table 2). The nasolacrimal duct and inferior turbinate were also preserved in all patients (Fig. 6A). Also, good ventilation of maxillary sinus was seen after surgery (Fig. 6B).

TABLE 2.

Summary of Patients’ Profile

| Patient | Anesthesia | Months After Operation |

| 1 | General | 90 |

| 2 | General | 81 |

| 3 | General | 81 |

| 4 | General | 75 |

| 5 | General | 73 |

| 6 | General | 73 |

| 7 | General | 58 |

| 8 | General | 57 |

| 9 | General | 52 |

| 10 | General | 37 |

| 11 | General | 32 |

| 12 | General | 28 |

| 13 | General | 28 |

| 14 | General | 16 |

| 15 | Local | 13 |

FIGURE 5.

Preoperative (A) and postoperative (B) Hess screen test results in a representative patient.

FIGURE 6.

Endoscopic view of the inferior turbinate (A) and the middle meatus (B) after operation.

DISCUSSION

Recently, a purely transnasal endoscopic approach has been documented for repair of orbital floor fracture.8–10 However, management was done through the middle meatus in the previous transnasal approach,8–10 resulting in limited view and difficult management. It is also difficult to manage the anterior and lateral side of bone fractures through the middle meatus, since the prolapsed orbital tissue blocks the view and makes management more difficult. Also, it is sometimes impossible to repair orbital floor fractures through the middle meatus, even though a view can be obtained with a side-view endoscope, or even though instruments can reach the fracture sites.

Hinohira et al9 reported that an extranasal procedure was used in 3 patients, and suggested that it is impossible to repair fracture using only transnasal approach, if the fracture was localized laterally in more than one-third of the orbital floor. However, our approach was performed in 8 patients with orbital facial fractures, localized laterally in more than half. And double visions were disappeared in all patients.

Otori et al10 advocated management through the inferior meatus in the repair of orbital floor fractures when necessary. However, the area of the orbital floor that can be reached by curved instruments of 12° to 120° through the small hole of the inferior meatus is 25% to 50% of the whole, smaller than that reached through the small hole of the middle meatus.12 Also, this access through the inferior meatus is not direct access to orbital floor fractures, resulting in limited view and difficult management with a side-viewing endoscope and curved instruments. In Otori's report,10 the percentage of resolved and improved patients with trapdoor fracture was lower than that in other patients. However, double vision in all patients with trapdoor fracture was disappeared in this study. Although our novel approach was different from surgery which Otori et al performed, this may be the reason of different result.

In our approach, direct access to orbital floor fractures through the anterior side of the nasolacrimal duct is possible. Orbital floor fractures can be observed with straight endoscopes. The nasolacrimal duct and inferior turbinate are also preserved with our method, resulting in no epiphora or empty nose.

The maxillary sinus around the ostium may be occupied by the prolapsed ocular contents, which include fatty tissue and extraocular muscles such as the medial and inferior rectus muscle, although in the method previously described the ostium was enlarged through the middle meatus.8–10 In these patients, it is very risky to enlarge the ostium from the nasal cavity, since the medial and inferior rectus muscles may be damaged. In our approach, fractures around the ostium can be identified through the maxillary sinus without management around the ostium, and the ostium can be enlarged from maxillary sinus. This means that our approach is safer.

Chief complaint of all patients was double vision, but not enophthalmos in this study. There were no patients with enophthalmos and no double vision in this study. However, this report showed that not only double vision but also enophthalmos could be treated by this novel surgery. And enophthalmos is an important cosmetic problem. Considering this, enophthalmos as well as double vision should be indications for this operation.

Plates and screws were not used in this study. When balloon was removed, regeneration of sinus mucosa and connective tissue, which covered and supported the fracture, was seen with fiberscope. All patients underwent follow-up, because there was the possibility of recurrence of double vision and enophthalmos. The possibility of recurrence because of no plates and screws was explained before surgery. All patients came to outpatient clinic and requested examination, since it is not difficult to examine the maxillary sinus through middle meatus with fiberscope. Although some patients underwent long-term follow-up of many years in this study, recurrence of double vision and enophthalmos was not seen. This may suggest usefulness of this surgery with balloon reconstruction.

The advantages of the novel approach presented herein appear to include: no external scar; less buccal discomfort; direct access and management to the orbital floor fractures through space anterior to the nasolacrimal duct, resulting in easier operation with a straight endoscope and instruments; easy management in the repair of anterior and lateral fractures; safe enlargement of the maxillary ostium after identification of orbital floor fractures near the maxillary ostium through the maxillary sinus; easy postoperative observation with an endoscope; no fixation with plates and screws is needed; no permanent materials are required to support the orbital floor; and repair with transnasal approach alone is possible even in patients with both floor and medial fractures, instead of combination of transnasal and extranasal approaches. This novel approach seems to be applicable to all orbital floor fractures, which cannot be treated by the previous purely transnasal endoscopic approach, in patients who request intranasal approach. Referring to Hinohira's report,9 this novel approach, but not the previous transnasal endoscopic approaches, should be considered, if the fracture exists laterally in more than one-third of the orbital floor from inside. However, the number of patients in this study was small. Further research, for example, research involving large number of patients for fracture size criteria, should be necessary to establish the safety and the efficacy of this approach.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ridgway EB, Chen C, Colakoglu S, et al. The incidence of lower eyelid malposition after facial fracture repair: a retrospective study and meta-analysis comparing subtarsal, subciliary, and transconjunctival incisions. Plast Reconstr Surg 2009; 124:1578–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bourgault S, Bordua-Robert MF, Molgat YM. Recurrent orbital cyst as a late complication of silastic implant for orbital floor fracture repair. Can J Ophthalmol 2011; 46:368–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta S, Aakalu VK, Ahmad AZ. Late-onset orbital hematoma secondary to alloplastic orbital implant mimicking transient ischemic attacks. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2011; 27:e18–e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mauriello JA, Jr, Hargrave S, Yee S, et al. Infection after insertion of alloplastic orbital floor implants. Am J Ophthalmol 1994; 117:246–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeFreitas J, Lucente FE. The Caldwell-Luc procedure: institutional review of 670 cases: 1975–1985. Laryngoscope 1988; 98:1297–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Low WK. Complications of the Caldwell-Luc operation and how to avoid them. Aust N Z J Surg 1995; 65:582–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soejima K, Shimoda K, Kashimura T, et al. Endoscopic transmaxillary repair of orbital floor fractures: a minimally invasive treatment. J Plast Surg Hand Surg 2013; 47:368–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ikeda K, Suzuki H, Oshima T, et al. Endoscopic endonasal repair of orbital floor fracture. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999; 125:59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hinohira Y, Yumoto E, Shimamura I. Endoscopic endonasal reduction of blowout fractures of the orbital floor. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2005; 133:741–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Otori N, Haruna S, Moriyama H. Endoscopic endonasal or transmaxillary repair of orbital floor fracture: a study of 88 patients treated in our department. Acta Otolaryngol 2003; 123:718–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki M, Nakamura Y, Nakayama M, et al. Modified transnasal endoscopic medial maxillectomy with medial shift of preserved inferior turbinate and nasolacrimal duct. Laryngoscope 2011; 121:2399–2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robey A, O’Brien EK, Leopold DA. Assessing current technical limitations in the small-hole endoscopic approach to the maxillary sinus. Am J Rhinol Allergy 2010; 24:396–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]