Abstract

Background

Tenofovir/Emtricitabine (TDF/FTC) is approved for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) against HIV infection. Adherence is critical for the success of PrEP but current adherence measurements are inadequate for real time adherence monitoring. We developed and validated a urine assay to measure tenofovir (TFV) to objectively monitor adherence to PrEP.

Methods

We developed a urine assay using high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry with high sensitivity/specificity for TFV that allowed us to determine TFV concentrations in log10 categories between 0–10,000 ng/mL. We validated the assay in 3 cohorts: 1) HIV-positive subjects with undetectable viral loads on a TDF/FTC-based regimen, 2) healthy subjects who received a single dose of TDF/FTC, 3) HIV-negative subjects receiving daily TDF/FTC as PrEP for 24 weeks.

Results

The urine assay detected TFV with greater sensitivity than plasma-based measures and with a window of measurements within 7 days from last tenofovir dose. Based on the urine log-linear clearance after last dose and its concordance with all detectable plasma levels, a urine TFV concentration > 1000 ng/mL was identified as highly predictive of presence of TFV in plasma >10 ng/mL. The urine assay was able to distinguish high or low adherence patterns within the last 48 hours (>1000 ng/mL vs. >10 to >100 ng/mL), as well as non-adherence (<10 ng/mL) extended over at least one week prior to measurement.

Conclusions

We provide proof-of-concept that a semi-quantitative urine assay measuring levels of TFV could be further developed into a point of care test and be a useful tool to monitor adherence to PrEP.

Keywords: HIV prevention, PrEP, urine tenofovir assay, adherence, Truvada

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has the potential for tremendous public health benefit by decreasing the still high incidence of new HIV infections. Tenofovir/Emtricitabine (TDF/FTC) used as PrEP is at least 90% effective in preventing HIV when taken daily (1, 2), and up to 99% effective when subjects are taking 7 daily doses per week (3). PrEP is recommended in the U.S. by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (4), and the World Health Organization globally (5), as a powerful tool for millions of individuals at substantial risk for HIV. Adherence to PrEP is critical for its success, but unfortunately we do not have adequate methods to monitor adherence in real time. Self-report and pill counts are unreliable methods for monitoring adherence (6, 7), particularly in populations at high risk of acquiring HIV like young men of color who have sex with men (yMSMc) (8).

How to accurately monitor and identify suboptimal adherence to PrEP, and develop strategic interventions to maintain adherence levels necessary for effectiveness, is a key gap in implementing this otherwise highly effective prevention therapy (6, 7). Therapeutic drug monitoring has been useful for assessment of adherence in other fields, specifically adherence to psychiatric medications, treatment of substance abuse disorders, and for improved blood pressure control in patients with resistant hypertension (9–12). Furthermore, behavioral changes are maximized when feedback is made available close to the behavior that needs modification (13, 14).

With regards to TDF/FTC, previously published means of measuring medication levels in patients receiving PrEP (dried blood spot, hair analysis) require sample collection procedures that may not be acceptable to patients outside of clinical trials (15, 16), are associated with delays in reporting that prevent implementation of timely effective interventions, and provide information that do not reflect recent PrEP use. Plasma TFV concentrations have been measured in clinical trials but can only provide information about adherence in the last 24 to 36 hours (17). Dried blood spot (DBS) has been used for adherence monitoring and typically provides an average adherence over the preceding three months (18–20), although preliminary data suggest that emtricitabine (FTC) measurement in DBS can be a marker of recent dosing (21). A 3-month window would be useful in the HIV treatment setting, but less relevant during PrEP where temporal adherence in regards to exposure may be more critical.

Alternative adherence strategies have been proposed, including intermittent PrEP (IPERGAY) timed around exposure periods (22) and prevention-effective adherence where PrEP is used only during periods of risk exposure to maximize prevention effectiveness and minimize unnecessary risk of medication toxicity and cost at times of decreased risk (23, 24). In addition, self-reported adherence to PrEP has correlated more closely with drug levels in open-label studies such as the PROUD study, where all 52 subjects who reported taking PrEP had detectable TFV levels in plasma (3, 25, 25). Thus, for the clinician evaluating PrEP use in patients, the key question is to identify real-time lapses in adherence that would leave the user at a higher risk for infection during periods of risk.

Finally, any test intended to be used for repeated monitoring in adolescents and young adults holding the highest incidence rates for HIV infection would have to be highly acceptable to this population; youth and young adults have been shown to prefer non-blood draw or needle-requiring assays in HIV testing (50.5% chose rapid oral swab vs. 30.3% chose traditional venipuncture vs. 19.2% chose rapid fingerstick blood test) (26), although preferences may differ when monitoring adherence to PrEP. A urine-based test would address many of these concerns.

The goal of this study was to develop and validate a urine assay to measure the concentration of TFV (the active metabolite of the prodrug tenofovir disoproxil fumarate or TDF) in order to objectively monitor adherence to PrEP in a clinical setting.

METHODS

Novel urine TFV assay

We developed a high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) plasma and urine assay with high sensitivity and specificity for tenofovir (TFV). This assay allowed us to determine urine TFV concentrations in log10 categories between 0 ng/mL to > 10,000 ng/mL (i.e. 0, > 10, > 100, > 1000, > 10,000 ng/mL). The assay was developed with modifications to a previously reported method (27, 28). Following protein precipitation (0.1 mL human plasma or urine or diluted urine sample) using 100% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid, containing deuterated internal standard (2H6-tenofovir, 50 ng/mL), the analytes were separated using gradient mobile phase on a Kinetex PFP column (2.6 μm, 4.6 × 100 mm) and analyzed by MS/MS (AB Sciex API4000, Foster City, CA). The multiple reaction monitoring of m/z 288.3 to 176.3 and 288.3 to 159.2 (sum of multiple ions) for TFV and m/z 294.3 to 182.2 for 2H6-tenofovir was used for analysis.

Study Design

We conducted 3 sequential cohort studies to validate the assay. Sample size for each cohort was 10 subjects, for a total of 30 subjects across 3 cohorts. Urine samples were first-catch samples collected at any time of day, and plasma and urine samples collected were approximately 1.5 cc.

The first cohort was a qualitative and semi-quantitative evaluation of the relationship of urine TFV to plasma TFV in 10 HIV-positive subjects who reported excellent adherence to medication, with undetectable HIV viral loads on a TDF/FTC-based regimen. Subjects kept a diary of the date/time of ART doses for the previous week. For all ten subjects, plasma and urine samples were collected at a single time point within a 4 week window after an undetectable HIV viral load. Data were compared to determine the positive and negative predictive value of the presence of TFV in urine using plasma TFV as the gold standard.

The second cohort was a quantitative evaluation of TFV clearance in plasma and urine over 7 days in 10 HIV-negative subjects who received a single dose of TDF/FTC under direct observation. This would allow us to estimate the relationship between the level of detectable TFV in urine versus an interval of up to 7 days since last administration of oral TDF/FTC.

The third cohort was a 24 week pilot study of 10 HIV-negative individuals on daily TDF/FTC for PrEP wherein urine TFV levels were assessed weekly (as the test provides adherence information over a one-week period) to assess a comprehensive depiction of adherence during the study period, and together with monthly plasma TFV levels in order to assess concordance between plasma and urine TFV levels. At each study visit, date and time of last TDF/FTC dose was collect by self-report. We also administered acceptability surveys to all subjects in this cohort at the beginning and end of the 24 week period.

Study Participants

Recruitment, enrollment, and study visits were conducted at Philadelphia FIGHT, a community based organization that provides comprehensive care to patients living with and at risk for HIV infection (http://fight.org/). Adults (≥18 years of age) followed at Philadelphia FIGHT who were HIV-positive with undetectable HIV viral loads in the previous 4 weeks on a TDF/FTC-based regimen were eligible for inclusion in Cohort 1. HIV-negative adults with normal baseline creatinine clearance were eligible for inclusion in Cohort 2. HIV-negative adults prescribed TDF/FTC as PrEP for HIV prevention at FIGHT’s youth clinic, Youth Health Empowerment Project, were eligible for inclusion in cohort 3. Subjects were recruited through word of mouth and advertising on social media sites. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects with the use of approved consent forms. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Philadelphia FIGHT and the University of Pennsylvania.

RESULTS

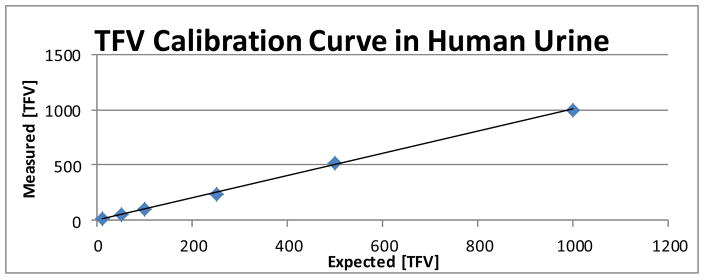

This study was conducted from January 2014 to December 2014. The measurement of plasma and urine TFV was found to be linear over the range of 10 – 1000 ng/mL with the limit of detection (LOD) of 5 ng/mL. Total chromatographic run-time was 5.0 minutes for each sample. LOD for TFV in human plasma and urine samples was determined and samples were analyzed quantitatively to show whether TFV was present or absent in clinical plasma and urine samples. Calibration curves were calculated for human urine and found to be highly accurate between 10 and 1000 ng/mL, with an accuracy range of 93.6% to 100% (r2 = 0.9962) (Figure 1). When the concentration of TFV in urine samples exceeded 1000 ng/mL, samples were diluted 20 or 50-fold with a control sample of urine (from someone not taking TDF) and reanalyzed.

Figure 1.

Tenofovir (TFV) calibration curve in human urine, which was found to be highly accurate over a concentration range of 10 to 1000 ng/mL, with an accuracy range of 93.6% to 100% (r2 = 0.9962). A known concentration of TFV was injected into a human urine sample (x axis) and measured using LC-MS/MS (y axis). The measurement urine TFV was found to be linear over the range of 10 – 1000 ng/mL with the limit of detection (LOD) of 5 ng/mL. [TFV] = tenofovir concentration.

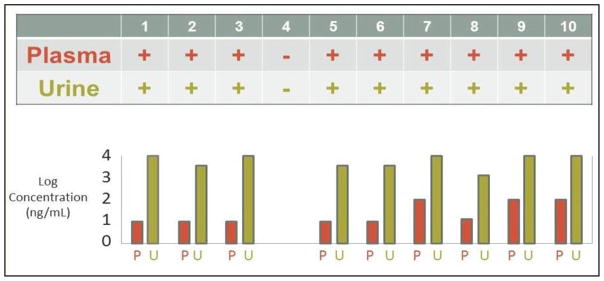

Cohort 1. Detection of Urine TFV Corresponds to Plasma Levels Within a 24 Hour Dosing Window (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Qualitative assessment, at a single time point, of the relationship of urine tenofovir (TFV) to plasma TFV in 10 HIV-positive subjects with undetectable HIV viral loads on a Tenofovir/Emtricitabine (TDF/FTC)-based regimen. All subjects with TFV in plasma also had detectable TFV in urine. Subject 4 had an undetectable viral load yet had no detectable TFV in blood or urine, and was later found to have stopped taking his antiretroviral therapy shortly after his viral load had been collected yet within 4 weeks of study sampling. Concentrations in plasma (P) and urine (U) are shown for each subject.

In our first cohort, ten HIV-positive patients with high adherence to a single-tablet HIV regimen containing tenofovir (as measured by having an undetectable viral load within 4 weeks of study testing) were asked to provide a single plasma and urine sample within 12 to 24 hours of their last dose of medication (see Table 1 for subject characteristics). We observed 100% concordance between presence of TFV in plasma and urine (PPV 100%, 95% CI, 0.63–1.0; NPV 100%, 95% CI, 0.05–1.0). TFV concentration was 3–4 log10 higher in urine than plasma. Surprisingly, subject 4 had an undetectable viral load yet had no detectable TFV in blood or urine. Follow-up inquiry identified that this subject had stopped taking his antiretroviral therapy shortly after his viral load had been collected yet within 4 weeks of sampling for this study.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| Characteristic | Cohort 1 (n = 10) | Cohort 2 (n = 10) | Cohort 3 (n = 10) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age – years | |||

| Mean | 43.2 | 37.2 | 20.4 |

| Range | 22–53 | 25–53 | 18–23 |

|

| |||

| Sex – number | |||

| Male | 4 | 8 | 10 |

| Female | 5 | 2 | 0 |

| Transgender (M to F) | 1 | 0 | 0 |

|

| |||

| Race – number | |||

| African American | 7 | 3 | 9 |

| Caucasian | 3 | 6 | 0 |

| Other | 0 | 1 | 1 |

|

| |||

| HIV status – % | |||

| HIV-positive | 100 | 0 | 0 |

|

| |||

| ART regimen | N/A | N/A | |

| Atripla | 7 | ||

| Stribild | 2 | ||

| Complera | 1 | ||

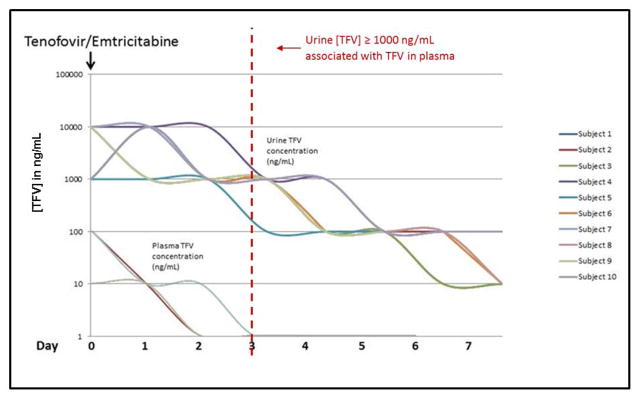

Cohort 2. Urine TVF Concentration Predictive of When Last Dose of TDF/FTC Was Taken

In our second cohort, we evaluated the kinetics of tenofovir elimination in plasma or urine over 7 days after a single oral administration in 10 healthy subjects (see Table 1 for subject characteristics). Decay rates for signal were tested after a single dose of TDF/FTC to evaluate TFV clearance in plasma and urine (Fig. 3). In this study, TFV was detected for >7 days in urine and 2–4 days in plasma after a single dose of TDF/FTC. Urine TFV was cleared in a log-linear fashion, with a direct correlation of change in urine levels to time since last dose. The urine assay was 2 log10 more sensitive than serum over 7 days. When TFV was detected in plasma (typically 2–3 days post-dose), urine TFV concentration was > 1000 ng/mL in most subjects, suggesting that urine tenofovir concentration of > 1000 ng/mL may be predictive of having taken TDF/FTC within the last two to three days from sampling.

Figure 3.

Measurement of tenofovir (TFV) clearance in plasma and urine over 7 days in 10 HIV-negative subjects who received a single dose of Tenofovir/Emtricitabine (TDF/FTC). After taking one dose of TDF/FTC, tenofovir (TFV) was measurable in plasma up to 4 days, and in urine for at least 7 days. TFV concentration decays in a log-linear fashion. When TFV was detected in plasma (out to 3 days post-dose), urine TFV concentration was > 1000 ng/mL in almost all subjects.

Cohort 3. Distinguishing Between Recent Adherence (within 48–72 hours), Low Adherence (within 1 week), and Non-Adherence to PrEP (last dose > 1 week prior)

We conducted a 24-week study of 10 HIV-negative subjects receiving daily PrEP to evaluate the concordance between plasma and urine TFV concentration over time (see Table 1 for subject characteristics). TFV was detected in 90% of urine samples collected weekly (concentration range: >10 to >10,000 ng/mL) and 73% of plasma samples collected monthly (concentration range: >10 ng/mL to >100 ng/mL). In all of the urine samples in which TFV was not detected (10%), TFV was not detected in plasma; we did not collect data from these patients to determine the reasons for nonadherence. 30% of subjects had at least one urine sample during the 24-week study period in which drug was no detected. Urine TFV concentration > 1000 ng/mL was highly predictive of presence of TFV in plasma (>10 ng/mL) (PPV 0.95, 95%CI, 0.80–0.99; NPV 0.79, 95%CI, 0.49–0.94). Since TDF is cleared from the plasma in 2–3 days, this suggests that the urine assay could be used to distinguish between recent adherence as defined by a dose of TDF within 48–72 hours (>1000 ng/mL), low adherence (>10 to >100 ng/mL), and non-adherence as defined by last dose more than one week prior (<10 ng/mL).

Acceptable to Young Men of Color Who Have Sex with Men

Acceptability of the assay was assessed in cohort 3 before and after the 6 month study period using a Likert scale from 1 to 6, where 1 is lowest and 6 is highest acceptability. Subjects were satisfied with the urine test as a means of monitoring adherence (mean before 5.7, after 5.6), with the side effects of urine testing (mean before 4.3, after 4.8), and with the demands of weekly testing (mean before 5.6, after 5.8). Subjects found it to be convenient (mean before 5.6, after 5.5) and were satisfied with their understanding of the importance of the test (mean before 5.8, after 5.9). They would recommend urine testing to others on PrEP (mean before 4.7, after 6.0) and would be interested in continuing urine testing after the study (mean before 5.9, after 5.8). Acceptability of the urine test in comparison to plasma testing was not assessed.

DISCUSSION

In this proof-of-concept study, we demonstrate that a semi-quantitative urine assay that measures TFV concentration could be used as an innovative non-invasive strategy to monitor real-time recent adherence to PrEP. Results of urine testing are available within one week, approximately the same turnaround time as viral load testing for HIV-positive patients, and there are no special processing requirements for urine samples after collection. Recent temperature stability studies demonstrate that samples are stable at room temperature for up to 14 days (data not shown). The urine assay is highly acceptable among yMSMc, provides high sensitivity and specificity relative to plasma TFV, predicts the approximate time when last dose of TDF/FTC was taken, and can distinguish between low, medium and high adherence to PrEP. The urine TFV assay may also be easier to implement clinically due to its expected ease of use (no specific laboratory processing or shipping requirements) and cost (roughly $40–50 depending on volume) to collect and process when compared to alternative tests. It can also be done at the same time (and using the same sample of urine) as other urine tests, including urine testing to monitor for nephrotoxicity and sexually transmitted infections.

Patient self-report may be more accurate in some populations than others, and an objective marker of adherence (akin to viral load in HIV-positive patients) could be extremely useful in certain settings. Importantly, urine TFV assessment can quickly provide information about whether someone is taking PrEP at all, and whether drug levels are expected to protect them from HIV infection at the time of testing. While tenofovir is known to be excreted in the urine, the assay described here represents the first to utilize urine to monitor adherence in the PrEP setting.

Our study also shows that monitoring urine TFV is feasible in a community health environment, which is the place where PrEP will have to be implemented in order to be effective. At our practice, at the present time, more than 50 patients who are receiving PrEP in a study setting are being monitored using urine TFV measurements (29). This approach allows us to flag clinical records that are identified as either not protected (urine TFV concentration < 10 ng/mL) or incompletely protected (urine TFV concentration > 10 or > 100 ng/mL) based on their most recent urine TFV concentrations. This information allows clinicians to focus their efforts on individuals currently on PrEP yet remaining at higher and immediate risk of acquisition of HIV. Results of urine monitoring could be used, much like viral load testing in HIV-positive patients, to engage patients in larger questions of risk awareness and stigma around use of PrEP.

Importantly, we document that clinical implementation of this assay is acceptable to a young high-risk MSM urban population. These results may also act as an impetus to develop additional urine-based assays for future candidate medications considered for PrEP programs, or to develop a point-of-care derivative of this assay (results available during the clinic visit) that could be used in a variety of clinical settings particularly resource-limited sites.

Our proof-of-concept study is limited by sample size and by not addressing additional variables that might affect urine drug concentration including urine flow, frequency of bladder emptying, and urinary pH. While these elements are not included in this analysis, this is a first-pass analysis of the reliability of a urine assay in patients taking daily TDF/FTC. However, the high concentrations of TFV in the urine as compared to plasma limit the potential impact of urine volume, if any. Larger studies will be needed to define more accurate thresholds for evaluation of adherence than those provided here. Another limitation of our study is that our sampling addresses the extent of excretion of tenofovir in a patient who has only taken one dose of TDF/FTC. Futures studies will need to confirm whether the decay rates in urine levels described here are also observed in subjects stopping TDF/FTC after a prolonged adherence period.

Urine TFV assessment can provide information within one week about whether someone is taking PrEP at all, and whether someone is taking PrEP well enough to protect them from HIV infection at the time of testing. Future studies should be done to develop point-of-care testing and to determine whether utilizing this type of assay to target adherence interventions ultimately improves adherence to PrEP and decreases the risk of HIV infection at the population level.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, University of Pennsylvania Center for AIDS Research [P30 AI 045008]. We would like to extend our sincere gratitude to Dr. James Hoxie and Dr. Ronald Collman from the Penn CFAR for their continuing and invaluable support throughout this work. Finally, we are extremely grateful to the women and men who participated in this trial and to the study staff for their commitment to this project.

The primary author has served as consultant to and has received a research grant from Gilead, the manufacturer of Truvada™.

References

- 1.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. iPrEx Study Team. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010 Dec 30;363(27):2587–2599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Partners PrEP Study Team. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012 Aug 2;367(5):399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson PL, Glidden DV, Liu A, et al. iPrEx Study Team. Emtricitabine-tenofovir concentrations and pre-exposure prophylaxis efficacy in men who have sex with men. Sci Transl Med. 2012 Sep 12;4(151):151ra125. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the united states – 2014 clinical practice guideline [homepage on the Internet] 2014 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/prepguidelines2014.pdf.

- 5.World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations. Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marrazzo JM, Ramjee G, Richardson BA, et al. VOICE Study Team. Tenofovir-based preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among african women. N Engl J Med. 2015 Feb 5;372(6):509–518. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, et al. FEM-PrEP Study Group. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among african women. N Engl J Med. 2012 Aug 2;367(5):411–422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hosek S, Siberry G, Bell M, et al. the Adolescent Trials Network for HIVAIDS Interventions (ATN) The acceptability and feasibility of an HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) trial with young men who have sex with men (YMSM) J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012 Dec 6; doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182801081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brunen S, Sommerlad D, Hiemke C. Medication adherence determined by therapeutic drug monitoring in psychiatric outpatients with co-morbid substance abuse disorders. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2011;21:A5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brunen S, Vincent PD, Baumann P, Hiemke C, Havemann-Reinecke U. Therapeutic drug monitoring for drugs used in the treatment of substance-related disorders: Literature review using a therapeutic drug monitoring appropriateness rating scale. Ther Drug Monit. 2011 Oct;33(5):561–572. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e31822fbf7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hiemke C. Clinical utility of drug measurement and pharmacokinetics: Therapeutic drug monitoring in psychiatry. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2008 Feb;64(2):159–166. doi: 10.1007/s00228-007-0430-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brinker S, Pandey A, Ayers C, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring facilitates blood pressure control in resistant hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 Mar 4;63(8):834–835. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonner K, Mezochow A, Roberts T, Ford N, Cohn J. Viral load monitoring as a tool to reinforce adherence: A systematic review. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013 Sep 1;64(1):74–78. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31829f05ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirby K. Bidding on the future: Evidence against normative discounting of delayed rewards. Journal of Experiental Psychology. 1997;126:54–70. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robbins R, Gouse H, Warne P, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of hair- and dried blood spot- derived ARV biomarkers as objective measures of treatment adherence in South Africa. IAPAC 10th International Conference on HIV Treatment and Prevention Adherence; Miami, Florida. June 28–30; Abstract #210. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olds PK, Kiwanuka JP, Nansera D, et al. Assessment of HIV antiretroviral therapy adherence by measuring drug concentrations in hair among children in rural uganda. AIDS Care. 2015;27(3):327–332. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.983452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hawkins T, Veikley W, St Claire RL, 3rd, Guyer B, Clark N, Kearney BP. Intracellular pharmacokinetics of tenofovir diphosphate, carbovir triphosphate, and lamivudine triphosphate in patients receiving triple-nucleoside regimens. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005 Aug 1;39(4):406–411. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000167155.44980.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng JH, Rower C, McAllister K, et al. Application of an intracellular assay for determination of tenofovir-diphosphate and emtricitabine-triphosphate from erythrocytes using dried blood spots. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2016 Apr 15;122:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2016.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu AY, Yang Q, Huang Y, et al. Strong relationship between oral dose and tenofovir hair levels in a randomized trial: Hair as a potential adherence measure for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) PLoS One. 2014 Jan 8;9(1):e83736. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng JH, Guida LA, Rower C, et al. Quantitation of tenofovir and emtricitabine in dried blood spots (DBS) with LC-MS/MS. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2014 Jan;88:144–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2013.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castillo-Mancilla JR, Bushman LR, Meditz A, et al. Emtricitabine-triphosphate in dried blood spots (DBS) as a marker of recent dosing. Presented at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI); Boston, MA. Feb, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Molina JM, Capitant C, Spire B, et al. ANRS IPERGAY Study Group. On-demand preexposure prophylaxis in men at high risk for HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2015 Dec 3;373(23):2237–2246. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haberer JE. Current concepts for PrEP adherence in the PrEP revolution: From clinical trials to routine practice. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2016 Jan;11(1):10–17. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haberer JE, Bangsberg DR, Baeten JM, et al. Defining success with HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: A prevention-effective adherence paradigm. AIDS. 2015 Jul 17;29(11):1277–1285. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): Effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2016 Jan 2;387(10013):53–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00056-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kowalczyk Mullins TL, Braverman PK, Dorn LD, Kollar LM, Kahn JA. Adolescent preferences for human immunodeficiency virus testing methods and impact of rapid tests on receipt of results. J Adolesc Health. 2010 Feb;46(2):162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nirogi R, Bhyrapuneni G, Kandikere V, et al. Simultaneous quantification of a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor efavirenz, a nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor emtricitabine and a nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor tenofovir in plasma by liquid chromatography positive ion electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. Biomed Chromatogr. 2009 Apr;23(4):371–381. doi: 10.1002/bmc.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Delahunty T, Bushman L, Fletcher CV. Sensitive assay for determining plasma tenofovir concentrations by LC/MS/MS. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2006 Jan 2;830(1):6–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koenig HC, Lalley-Chareczko L, Sima J, et al. Prospective use of urine tenofovir assay to monitor adherence to PrEP. Presented at the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (IAPAC) conference Adherence; Fort Lauderdale, FL. May 9–11, 2016.2016. [Google Scholar]