Abstract

BACKGROUND

Human metapneumovirus (hMPV) causes upper and lower respiratory tract infections (URIs and LRIs, respectively) in healthy and immunocompromised patients; however, its clinical burden in patients with cancer remains unknown.

METHODS

In a retrospective study of all laboratory‐confirmed hMPV infections treated at the authors’ institution between April 2012 and May 2015, clinical characteristics, risk factors for progression to an LRI, treatment, and outcomes in patients with cancer were determined.

RESULTS

In total, 181 hMPV infections were identified in 90 patients (50%) with hematologic malignancies (HMs), in 57 (31%) hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) recipients, and in 34 patients (19%) with solid tumors. Most patients (92%) had a community‐acquired infection and presented with URIs (67%), and 43% developed LRIs (59 presented with LRIs and 19 progressed from a URI to an LRI). On multivariable analysis, an underlying HM (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 3.11; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.12‐8.64; P = .029), nosocomial infection (aOR, 26.9; 95% CI, 2.79‐259.75; P = .004), and hypoxia (oxygen saturation [SpO2], ≤ 92%) at presentation (aOR, 9.61; 95% CI, 1.98‐46.57; P = .005) were identified as independent factors associated with LRI. All‐cause mortality at 30 days from hMPV diagnosis was low (4%), and patients with LRIs had a 10% mortality rate at day 30 from diagnosis; whereas patients with URIs had a 0% mortality rate.

CONCLUSIONS

hMPV infections in patients with cancer may cause significant morbidity, especially for those with underlying HM who may develop an LRI. Despite high morbidity and the lack of directed antiviral therapy for hMPV infections, mortality at day 30 from this infection remained low in this studied population. Cancer 2017;123:2329–2337. © 2017 American Cancer Society.

Keywords: cancer, death, human metapneumovirus (hMPV), leukemia, pneumonia, respiratory virus, stem cell transplantation

Short abstract

Human metapneumovirus infections in patients with cancer may cause significant morbidity, especially in those with underlying hematologic malignancies who may develop a lower respiratory infection. Despite high morbidity and the lack of directed antiviral therapy for human metapneumovirus infections, mortality from this infection at day 30 and day 90 remains low in the studied population.

INTRODUCTION

In 2001, human metapneumovirus (hMPV), an enveloped, nonsegmented, negative RNA‐Paramyxoviridae virus, was discovered in the Netherlands.1 It has been reported in 4% of adults and 13% of children with community‐acquired pneumonia.2, 3, 4 The virus can affect all age groups with upper respiratory infections (URIs) and lower respiratory tract infections (LRIs); however, severe disease has been described in young children5 and older adults.6 The diagnosis of hMPV from respiratory specimens depends on molecular assays (ie, reverse transcriptase‐polymerase chain reaction), which are more sensitive than older methods like direct fluorescent antibody, viral cultures, and serology.7 In 2012, we adopted a new molecular assay (FilmArray Respiratory Panel; BioFire Diagnostics, LLC, Salt Lake City, Utah), which enhanced the diagnosis of patients with respiratory viral infections secondary to hMPV and other respiratory viruses from respiratory specimens.hMPV infections in immunocompromised hosts have been described in small case series. In patients with cancer, hMPV incidence is similar to that in the immunocompetent population (approximately 7%).8, 9 hMPV‐associated LRI has been reported in as many as 41% of patients with cancer8 and 100% of children undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT).10 Yet hMPV‐associated mortality remains low8, 9, 11 unless bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) findings are positive for the virus.12 These studies were limited by small sample size and inadequate power to determine risk factors and outcomes of hMPV infections in patients with cancer and associated mortality and morbidity.13 Although supportive measures may be in place, hMPV treatment remains a challenge, because the only in vitro, active drug choice is ribavirin for inhibition of hMPV replication.14, 15 In addition, intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIGs) with or without ribavirin have been used in patients with hMPV infections16, 17, 18 with lack of systematic evaluation for efficacy. The ECIL 4 European Conference on Infections in Leukemia addressed community‐acquired respiratory viruses, including hMPV; however, this therapy lacks systematic evaluation.19

In this large, retrospective study, our objective was to determine the clinical characteristics and outcomes of hMPV infections in patients with cancer who are immunocompromised. We attempted to characterize the risk factors associated developing hMPV‐associated LRIs, hMPV‐associated mortality, and all‐cause mortality to identify patients with specific underlying malignancies who are at higher risk for these outcomes and may be suitable targets for antiviral therapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was conducted at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, Tex). The Infection Control database was searched to identify all patients who had laboratory‐confirmed hMPV infections between April 2012 and May 2015. The BioFire FilmArray Respiratory Panel at our institution was used to diagnose respiratory viral infections, including hMPV. The Institutional Review Board approved the protocol, and a waiver for informed consent was granted.

Data Collection

We reviewed patient medical records and collected the following data: demographics, including age, sex, and race; smoking history; cancer type; and cancer status (complete remission or active disease) at the time of infection. For HCT recipients, we reviewed the underlying cancer, the type of transplantation (matched‐related donor, matched‐unrelated donor, haploidentical, mismatched, and autologous), the source (bone marrow, cord, or peripheral), date of HCT, receipt of myeloablative versus nonmyeloablative conditioning regimens and type of immunosuppressive therapy used, time of engraftment, history and type of graft‐versus‐host‐disease (acute or chronic), grade and organ involvement, and cytomegalovirus serostatus. For hMPV infection episodes, we included coinfections within 30 days before and after the hMPV episode, if any; date of symptom onset; type of infection at the time of presentation (community‐acquired vs nosocomial acquisition); infection site at presentation (URI vs LRI); absolute neutrophil count (ANC); absolute lymphocyte count (ALC); and γ‐globulin level (when available) up to 30 days before presentation. Systemic steroid use and doses were recorded within 30 days before the infection diagnosis. We also collected data on outcomes and therapy, including whether patients required hospitalization, length of stay if admitted, intensive care unit admission (at onset or later), use of mechanical ventilation, receipt of ribavirin (oral vs aerosolized form), IVIGs, and date and cause of death. Oxygen saturation at presentation was recorded as well as the lowest oxygen saturation during the infection and the type of oxygen supplementation (nasal cannula, venti‐mask, face‐mask, vapotherm, or bilevel positive airway pressure).

Definitions

hMPV cases were defined in this study as situations in which a patient with cancer developed acute, symptomatic respiratory illness and had a positive nasal wash result and/or a BAL finding indicating hMPV. Community‐acquired cases occurred when patients developed symptoms while they were outpatients and/or before hospitalization or within the first 5 days after admission.20, 21 Symptomatic hMPV infections that developed >5 days after hospitalization were considered nosocomially acquired. URI was defined as the development of rhinorrhea, nasal or sinus congestion, otitis media, pharyngitis, cough, or shortness of breath with no hypoxemia or infiltrates on chest radiographic imaging in patients who had a positive hMPV test result in a nasal wash. LRI was defined when new or worsening pulmonary infiltrates were observed on chest radiograph and/or when hMPV was detected in a lower respiratory specimen, such as endotracheal tube aspirate, sputum, or BAL. Neutropenia was defined as an ANC <500/mL, and lymphopenia was defined as an ALC <200/mL. All‐cause mortality was assessed within 30 days and 90 days from hMPV diagnosis and was attributed to hMPV if a patient had a persistent or progressive hMPV LRI with respiratory failure at the time of death.

Statistical Analysis

We evaluated patient characteristics using descriptive statistics. Categorical variables were compared using the chi‐square test or the Fisher exact test, and continuous variables were compared using the Student t test or the Wilcoxon rank‐sum test. Multivariable logistic regression was used to identify the risk factors associated with LRI, and the results are reported as adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A secondary model restricted to those patients who presented with URI (n = 122) was also constructed to identify risk factors for progression from URI to LRI. The probability of progression from URI to LRI between 3 cancer groups (hematologic malignancies [HM], HCT, and solid tumor) was compared using a Kaplan‐Meier failure curve. A 2‐sided P value of .05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed sing Stata software (version 13; StataCorp, College Station, Tex).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

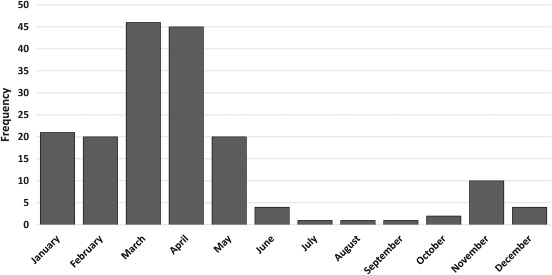

Between April 2012 and May 2015, 181 laboratory‐confirmed hMPV infections were identified in patients with cancer; 34 patients (19%) had solid tumors, 57 (31%) were HCT recipients (in remission), and 90 (50%) had HM. Patients with relapsed HM after HCT were included in the HM group. Patients’ characteristics are depicted in Table 1. The median age was 59 years (range, 1‐88 years), and 60% were men. Most patients were non‐Hispanic whites (n = 111; 61%) and had never smoked (n = 126; 70%). Among patients with HM or post‐HCT status, multiple myeloma was the most common underlying malignancy (30%). The majority of patients (92%) had community‐acquired infections that were detected throughout the year with a peak during April and May (Fig. 1) and had occurred with URI (67%). The overall LRI rate was 43%, and patients with HM had the highest rate of LRI (54%). The all‐cause mortality rate at days 30 and 90 from infection diagnosis was 4% and 7%, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics and Outcomes of 181 Patients With Cancer and Human Metapneumovirus Infections

| No. of Patients (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Solid Tumors | HCT, Remission | HM | Total |

| Total cohort | 34 (19) | 57 (31) | 90 (50) | 181 (100) |

| Age: Median [range] y | 62 [3‐86] | 56 [16‐76] | 59 [1‐88] | 59 [1‐88] |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 16 (47) | 30 (53) | 63 (70) | 109 (60) |

| Female | 18 (53) | 27 (47) | 27 (30) | 72 (40) |

| Racea | ||||

| Non‐Hispanic white | 16 (47) | 36 (63) | 59 (66) | 111 (61) |

| Hispanic | 11 (32) | 12 (21) | 16 (18) | 39 (22) |

| Black | 5 (15) | 6 (11) | 8 (9) | 19 (11) |

| Asian | 1 (3) | 2 (3) | 2 (2) | 5 (3) |

| Other | 1 (3) | 1 (2) | 4 (4) | 6 (3) |

| Smokinga | ||||

| Never smoker | 22 (65) | 40 (70) | 64 (71) | 126 (70) |

| Former smoker | 11 (32) | 16 (28) | 22 (24) | 49 (27) |

| Current smoker | 1 (3) | 1 (2) | 3 (3) | 5 (3) |

| Type of malignancy | ||||

| AML | 0 (0) | 12 (21) | 14 (16) | 26 (14) |

| ALL | 0 (0) | 9 (16) | 13 (14) | 22 (12) |

| CML | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | 6 (7) | 8 (4) |

| CLL | 0 (0) | 3 (5) | 4 (4) | 7 (4) |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 5 (6) | 6 (3) |

| NHL | 0 (0) | 11 (19) | 10 (11) | 21 (12) |

| MDS | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | 4 (4) | 6 (3) |

| MM | 0 (0) | 14 (25) | 30 (33) | 44 (24) |

| AA | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) |

| Other | 34 (100) | 1 (2) | 4 (4 | 39 (22) |

| Type of HCT | ||||

| None | 34 (100) | 0 | 64 (71) | 98 (54) |

| MRD | 0 (0) | 20 (35) | 2 (2) | 22 (12) |

| MUD | 0 (0) | 16 (28) | 3 (33) | 19 (10) |

| Haploidentical | 0 (0) | 3 (5) | 1 (1) | 4 (2) |

| Cord | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | 2 (2) | 4 (2) |

| Mismatched | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Autologous | 0 (0) | 15 (26) | 18 (20) | 33 (18) |

| HCT cell source | ||||

| Bone marrow | 0 (0) | 7 (12) | 0 (0) | 7 (4) |

| Cord | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | 2 (2) | 4 (2) |

| Peripheral | 0 (0) | 48 (84) | 24 (27) | 72 (40) |

| Type of infection | ||||

| Community‐acquired | 32 (94) | 52 (91) | 82 (91) | 166 (92) |

| Nosocomial | 2 (6) | 5 (9) | 8 (9) | 15 (8) |

| Site of infection at the time of presentation | ||||

| URI | 25 (74) | 43 (75) | 54 (60) | 122 (67) |

| LRI | 9 (26) | 14 (25) | 36 (40) | 59 (33) |

| Progression from URI to LRI | ||||

| No | 24 (71) | 38 (67) | 41 (46) | 103 (57) |

| Yes | 1 (3) | 5 (9) | 13 (14) | 19 (10) |

| Time to progression from URI to LRI: Median [range], db | 1 | 12 [1‐30] | 8 [1‐30] | 8 [1‐30] |

| Overall LRI | ||||

| No | 24 (71) | 38 (67) | 41 (46) | 103 (57) |

| Yes | 10 (29) | 19 (34) | 49 (54) | 78 (43) |

| Steroids within 30 d before hMPV | ||||

| No | 25 (74) | 39 (70) | 52 (58) | 116 (64) |

| Yes | 9 (26) | 18 (32) | 38 (42) | 65 (36) |

| Lymphopeniaa | ||||

| No | 31 (91) | 54 (95) | 75 (83) | 160 (88) |

| Yes | 2 (6) | 3 (5) | 15 (17) | 20 (11) |

| Neutropeniaa | ||||

| No | 29 (85) | 56 (98) | 69 (77) | 154 (85) |

| Yes | 4 (12) | 1 (2) | 21 (23) | 26 (14) |

| Hypoxia at presentation | ||||

| >92% | 29 (85) | 53 (93) | 82 (91) | 164 (91) |

| ≤92% | 5 (15) | 4 (7) | 8 (9) | 17 (9) |

| Ribavirin | ||||

| URI stage | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

| LRI stage | 0 | 2 (4) | 1 (1) | 3 (2) |

| IVIG | ||||

| URI stage | 1 (3) | 7 (13) | 6 (7) | 14 (8) |

| LRI stage | 0 (0) | 3 (5) | 16 (18) | 19 (11) |

| Coinfection before hMPV | ||||

| Pulmonary | 5 (15) | 11 (19) | 15 (7) | 31 (17) |

| Extrapulmonary | 1 (3) | 1 (2) | 6 (7) | 8 (4) |

| Coinfection after hMPV | ||||

| Pulmonary | 3 (9) | 2 (4) | 4 (4) | 9 (5) |

| Extrapulmonary | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 2 (2) | 3 (2) |

| Hospital admission secondary to infectionc | 15/29 (52) | 21/30 (70) | 44/78 (56) | 80/137 (58) |

| Length of hospital stay: Median [range], dc | 4 [2‐20] | 6 [3‐17] | 6 [2‐29] | 6 [2‐29] |

| ICU at onset | 2 (6) | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 4 (2) |

| ICU later during the illness | 1 (3) | 1 (2) | 4 (4) | 6 (3) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 3 (9) | 2 (4) | 3 (3) | 8 (4) |

| Oxygen supplement | 10 (29) | 12 (21) | 26 (29) | 48 (27) |

| All‐cause mortality, 30 d | 1 (3) | 1 (2) | 6 (7) | 8 (4) |

| All‐cause mortality, 90 d | 2 (6) | 2 (4) | 8 (9) | 12 (7) |

Abbreviations: AA, aplastic anemia; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myelogenous leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CML, chronic myelogenous leukemia; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; HM, hematologic malignancy; hMPV, human metapneumovirus; ICU, intensive care unit; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; LRI, lower respiratory tract infection; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; MM, multiple myeloma; MRD, matched‐related donor; MUD, matched‐unrelated donor; NHL, non‐Hodgkin lymphoma; URI, upper respiratory tract infection.

One patient was missing information.

This analysis was restricted to patients who progressed from URI to LRI (n = 19).

Analysis of the time to progression excluded patients who were admitted before hMPV diagnosis.

Figure 1.

The seasonal distribution of human metapneumovirus infections between April 2012 and May 2015 is illustrated (n = 181).

hMPV‐Associated LRI

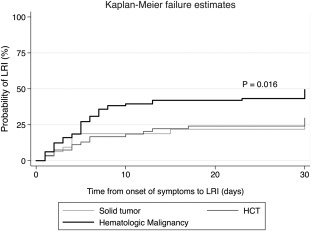

Patient characteristics associated with LRI are depicted in Table 2. Patients with LRI were more likely than those with URI to have HM (aOR, 3.11; 95% CI, 1.12‐8.64; P = .029), nosocomially acquired hMPV(aOR, 26.9; 95% CI, 2.79‐259.75; P = .004), and hypoxia (oxygen saturation [SpO2], ≤ 92%) at presentation (aOR, 9.61; 95% CI, 1.98‐46.57; P = .005). When the logistic model was restricted only to patients who presented with URI, having an underlying HM was a significant predictor for progression to LRI (aOR, 27.23; 95% CI, 1.44‐514.82; P = .028), as did having nosocomially acquired infections (aOR, 500.41; 95% CI, 15.79‐15,854.59; P < .001). The Kaplan‐Meier failure curve indicated a significantly higher incidence of LRI in the HM group versus the solid tumor or HCT groups (P = .016) (Fig. 2). Age, sex, smoking status, immunodeficiency status based on ANC and ALC values, steroid use, and the presence of pulmonary copathogens before hMPV diagnosis did not significantly affect progression to LRI in this cohort.

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics Associated With Human Metapneumovirus Lower Respiratory Tract Infection

| No. (%) | Total Cohort, n = 178a | Restricted to Patients who Presented With URI, n = 122 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | URI | LRI | Unadjusted OR [95% CI] | P | Adjusted OR [95% CI] | P | Adjusted OR [95% CI] | P |

| All patients | 103 (57) | 78 (43) | ||||||

| Age: Median/range, yb | 59/1‐84 | 59/7‐88 | 1.08/0.93‐1.26 | .288 | 1.15/0.94‐1.39 | .167 | 1.06/0.77‐1.45 | .718 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Men | 59 (54) | 50 (46) | 1.00 | |||||

| Women | 44 (61) | 28 (39) | 0.75 [0.41‐1.38] | .354 | ||||

| Race | ||||||||

| Non‐Hispanic white | 55 (50) | 56 (50) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Hispanic | 27 (69) | 12 (31) | 0.44 [0.2‐0.95] | .036 | 0.46 [0.18‐1.13] | .091 | 0.54 [0.08‐3.51] | .521 |

| Black | 12 (63) | 7 (37) | 0.57 [0.21‐1.56] | .277 | 0.64 [0.2‐2.10] | .464 | 4.6 [0.84‐25.38] | .079 |

| Asian/other | 9 (82) | 2 (18) | 0.21 [0.05‐1.06] | .058 | 0.15 [0.03‐0.87] | .035 | 0.56 [0.05‐6.3] | .635 |

| Smoking | ||||||||

| Never | 71 (56) | 55 (44) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Former/current smoker | 31 (57) | 23 (43) | 0.96 [0.5‐1.82] | .896 | 0.75 [0.34‐1.65] | .475 | 1.19 [0.3‐4.77] | .804 |

| Underlying condition | ||||||||

| Solid tumor | 24 (71) | 10 (29) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| HCT, in remission | 38 (67) | 19 (33) | 1.2 [0.48‐3.01] | .698 | 1.09 [0.37‐3.23] | .877 | 4.35 [0.23‐83.51] | .33 |

| HM | 41 (46) | 49 (54) | 2.89 [1.23‐6.69] | .015 | 3.11 [1.12‐8.64] | .029 | 27.23 [1.44‐514.82] | .028 |

| Type of infection | ||||||||

| Community‐acquired | 102 (61) | 64 (39) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Nosocomial | 1 (7) | 14 (93) | 22.31 [2.86‐173.79] | .003 | 26.9 [2.79‐259.75] | .004 | 500.41 [15.79‐15,854.59] | < .001 |

| Steroids | ||||||||

| No | 70 (60) | 46 (40) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Yes | 33 (51) | 32 (49) | 1.48 [0.8‐2.72] | .213 | 0.89 [0.42‐1.90] | .769 | 0.35 [0.08‐1.64] | .184 |

| Immunodeficiency | ||||||||

| None | 86 (61) | 56 (39) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Neutropenia | 9 (50) | 8 (50) | 1.54 [0.57‐4.11] | .393 | 0.47 [00.12‐1.79] | .268 | 0.16 [0‐5.11] | .299 |

| Lymphopenia | 5 (42) | 7 (58) | 2.15 [0.65‐7.11] | .210 | 1.16 [0.24‐5.62] | .853 | 1.59 [0.13‐19.44] | .717 |

| Both | 2 (25) | 6 (75) | 4.61 [0.89‐23.64] | .067 | 3.39 [0.44‐26.43] | .244 | 3.21 [0.13‐79.16] | .476 |

| Hypoxia at presentation | ||||||||

| >92% | 89 (58) | 64 (42) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| ≤92% | 3 (25) | 9 (75) | 4.17 [1.09‐16.02] | .037 | 9.61 [1.98‐46.57] | .005 | 10.08 [0.55‐184.45] | .119 |

| IVIG at URI stage | ||||||||

| No | 92 (55) | 75 (45) | 1.00 | — | — | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 11 (79) | 3 (21) | 0.33 [0.09‐1.24] | .102 | — | — | 0.6 [0.08‐4.61] | .623 |

| Pulmonary copathogen before hMPV diagnosis | ||||||||

| None | 90 (60) | 60 (40) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Pulmonary | 13 (42) | 18 (58) | 2.08 [0.95‐4.55] | .068 | 1.69 [0.64‐4.44] | .289 | 0.22 [0.02‐2.57] | .226 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence internal; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplant; HM, hematologic malignancy; hMPV, human metapneumovirus; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; LRI, lower respiratory tract infection; OR, odds ratio; URI, upper respiratory tract infections.

Complete information on all variables included in the model was available for 178 patients.

Age was categorized into 10‐year intervals.

Figure 2.

Kaplan‐Meier failure curves illustrate the probability of progression to lower respiratory tract infection (LRI) over time (restricted to patients who presented with upper respiratory infection). HCT indicates hematopoietic cell transplantation.

Among the 78 patients who had LRI, 33 (42%) underwent BAL, and hMPV was detected in 23 (70%). Escherichia coli was detected in 1 patient, and no pathogens were detected in the remaining 9 patients. Copathogens were recovered from BAL samples of only 7 patients who were positive for LRI and hMPV and included cytomegalovirus (n = 1), E. coli (n = 1), methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (n = 1), methicillin‐sensitive S. aureus (n = 1), parainfluenza virus (PIV) 3 (n = 1), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) (n = 1), coronavirus 229E (n = 1), and Arthrographis (n = 1).

All‐Cause and hMPV‐Associated Mortality

Twelve patients died within a median of 15 days (range, 1‐45 days) after their hMPV diagnosis, and mortality rates were similar for all 3 cancer groups. Of these, 4 patients had probable hMPV‐attributed deaths (3 with relapsed or refractory HM and 1 matched‐unrelated donor and HCT recipient) after progression to respiratory failure within 18 days of hMPV diagnosis (range, 5‐36 days). Only 2 patients with hMPV‐associated death had pulmonary coinfections, 1 with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia and the other with Aspergillus terreus. The remaining 8 patients died from cancer relapse (n = 4) and other causes (n = 4) at a median of 22 days (range, 1‐45 days).

Antiviral Therapy: Ribavirin and IVIG

Five patients received ribavirin therapy (2 at the URI stage and 3 at the LRI stage), and 31 patients received IVIG (14 at the URI stage and 17 at the LRI stage). Of the 4 patients who died with respiratory failure, 1 received IVIG, and 1 received aerosolized ribavirin with IVIG at the LRI stage; whereas the others had not received antiviral therapy.

Airflow Decline

Pulmonary function tests after infection were performed in 22 HCT recipients (16 allogeneic HCT and 6 autologous HCT recipients) at an average of 60 days (range, 18‐520 days) from hMPV diagnosis. Evidence of airflow decline, defined as a drop of at least 15% in forced expiratory volume (FEV1) from pre‐HCT to postinfection, was observed in 8 patients (36%), including 4 who underwent matched‐related donor HCT, 3 who underwent matched‐unrelated donor HCT, and 1 who underwent autologous HCT). The median delta drop in FEV1 was 26% (range, 16%‐49%) within a median of 56 days (range, 33‐307 days) after hMPV infection. Five of these patients had LRI; however, all patients survived.

γ‐Globulin Levels

In a subgroup of 39 HCT recipients who had γ‐globulin levels checked at the time of presentation, significantly higher levels of γ‐globulin were observed in patients with URI (1032 ± 561 mg/dL) versus those with LRI (566 ± 197 mg/dL; P = .01).

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective study of hMPV infections in 181 patients with cancer, we report a high incidence of LRI (43%) and low overall mortality (7%) after these infections. Risk factors associated with LRI were underlying HM, nosocomially acquired infection, and hypoxia at presentation. Patients with HM were more likely to progress from URI to LRI than HCT recipients or patients with solid tumors. All patients who died within 30 days from hMPV diagnosis had developed an LRI (mortality rate, 10% in patients with LRI vs 0% in patients with URI).

An overall LRI rate of 43% was observed in these patients with cancer. This finding is higher when measured against previous studies, which reported an LRI rate of 28% to 41% in patients who had cancer and an hMPV diagnosis.22 The incidence of hMPV LRI was consistent with that reported for other respiratory viruses among HCT recipients and patients with HM.22, 23 Several risk factors associated with LRI were identified. Hypoxia at the time of diagnosis was a substantial risk factor in the multivariable analysis. Hypoxia and a supplemental oxygen requirement at diagnosis are associated with higher rates of LRI and death in patients with cancer who have RSV, PIV, and influenza.23 Oxygen use may be a surrogate marker for the extent of lung injury, which may lead to poor outcomes.24 It is interesting to note that an underlying diagnosis of HM significantly increased the risk for LRI. Currently, there are limited data on hMPV infections in patients with HM and their impact; however, underlying HM was reported as a significant risk factor for progression to LRI in patients with PIV‐associated respiratory infections.25 Patients with HM might have a high level of immunosuppression caused by active chemotherapy at the time of hMPV infection or because of their underlying relapsed or refractory disease with subsequent prolonged cytopenias compared with engrafted HCT recipients who are in remission.26, 27 Nosocomial acquisition of hMPV was associated with a significantly higher risk for hMPV‐associated LRI. Substantial numbers of nosocomial hMPV infections also were described in a previous hMPV study of patients with HM.8 Respiratory viruses can be transmitted from either asymptomatic or symptomatic patients, family members, or health care workers. This highlights the importance of infection‐control measures, because nosocomial infections were associated with higher morbidity rates in our study population.

Neutropenia and/or lymphopenia have been described as major risk factors for LRI and death associated with other respiratory viruses.22, 23 This was not observed in our study or in other studies that examined patients with cancer who had hMPV and may be explained by the finding that only a few patients had these risk factors.8 Similarly, other risk factors for progression to LRI and death (ie, older age, smoking history, and steroid use) reported with other respiratory viruses were not observed in this population with hMPV infection.

Overall mortality rates of 4% at day 30 and 7% at day 90 are consistent with previous smaller case series in patients with cancer.8, 9, 11, 28, 29 Also, the rate of hMPV‐associated death was only 2%. When evaluated against other respiratory viral infections in patients with cancer (ie, RSV or PIV), the lower incidence of mortality associated with hMPV infections in our patients with cancer suggests a difference in viral factors (genotype, viral fitness, or virulence) rather than host factors, and further study is warranted.

Ribavirin, which is mainly used to treat RSV infections in HCT recipients,23, 30, 31, 32 has demonstrated in vitro activity against hMPV by a direct antiviral effect14 and in mouse models by reducing viral replication.15 In a few case reports, the use of ribavirin was associated with good outcomes after severe hMPV infections in patients with cancer.17, 33, 34, 35 In our study, the mortality rate remained low despite the lack of ribavirin use in most of patients, and particularly in those with LRIs.

In a subgroup analysis of 39 HCT recipients who had γ‐globulin levels checked at the time of presentation, we observed significantly higher levels of γ‐globulins in patients with URI than in those with LRI. Levels of γ‐globulin are much lower in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia who have a history of any infection than in those who have chronic lymphocytic leukemia with no history of infection.36 This suggests that higher γ‐globulin levels can protect against worse outcomes. Standard IVIG administration can inhibit hMPV replication in vitro,14 so we hypothesize that IVIG administration may be beneficial in HCT recipients to prevent progression from hMPV URI to LRI; however, an association between IVIG administration and LRI prevention could not be demonstrated in our study and needs to be systematically determined in future trials. We did not identify other significant risk factors, such as age, smoking status, levels of immunodeficiency (ANC, ALC), type of conditioning regimen, cytomegalovirus serostatus of the donor or recipient, graft‐versus‐host‐disease, time of engraftment, HCT cell source, or HCT recipient exposure to steroids. In a 2015 study, receipt of ≥ 1 mg/kg of steroids within 2 weeks before diagnosis was the only significant risk factor identified for progression to LRI according to a multivariate regression analyses of 118 HCT recipients.37

This retrospective study has many limitations, including the lack of hMPV quantification in respiratory secretions, which can indicate disease severity, as observed in hMPV studies in populations for which higher viral loads have been associated with increased risk for LRI and hospitalization.38, 39 Several studies have suggested that severity of disease and symptom manifestations varies with hMPV genotype,40, 41 but this information was not available in our cohort.

For patients with cancer, the burden of hMPV infection is similar to the burden associated with other respiratory viral infections. However, the mortality rate after hMPV infections is lower than that associated with other related viruses, such as RSV. Patients with HM, nosocomial infections, and hypoxia at presentation should be closely monitored for risk of progression to LRI. Because hMPV may be acquired nosocomially, leading to worse outcomes and high morbidity, strict adherence to infection‐control measures and universal hand hygiene should be underscored. The significance of γ‐globulin levels and the role of IVIG in preventing hMPV‐associated LRI and/or mortality should be determined in future studies, especially among HCT recipients and patients with HM.

FUNDING SUPPORT

This study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute under award P30CA016672 and used the Cancer Center Support Grant resources.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors made no disclosures.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Firas El Chaer: Conceptualized and designed the study, clinical research and data collection, helped with data acquisition, writing–initial draft, writing–revisions and final review, and responsible for overall content as guarantor. Dimpy P. Shah: Conceptualized and designed the study, performed statistical analyses, writing–initial draft, writing–revisions and final review, and responsible for overall content as guarantor. Joumana Kmeid: Clinical research and data collection and writing–revisions and final review Ella J. Ariza‐Heredia: Helped with data acquisition and writing–revisions and final review. Chitra M. Hosing: Helped with data acquisition and writing–revisions and final review. Victor E. Mulanovich: Writing–revisions and final review. Roy F. Chemaly: Conceptualized and designed the study, helped with data acquisition, writing–initial draft, writing–revisions and final review, and responsible for overall content as guarantor.

We thank Ms. Brenda Moss‐Feinberg, Department of Scientific Publications at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, for her editorial support.

REFERENCES

- 1. van den Hoogen BG, de Jong JC, Groen J, et al. A newly discovered human pneumovirus isolated from young children with respiratory tract disease. Nat Med. 2001;7:719‐724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jain S, Williams DJ, Arnold SR, et al. Community‐acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among US children. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:835‐845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, et al. Community‐acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among US adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:415‐427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Johnstone J, Majumdar SR, Fox JD, Marrie TJ. Human metapneumovirus pneumonia in adults: results of a prospective study. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:571‐574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Williams JV, Tollefson SJ, Heymann PW, Carper HT, Patrie J, Crowe JE. Human metapneumovirus infection in children hospitalized for wheezing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:1311‐1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boivin G, De Serres G, Hamelin ME, et al. An outbreak of severe respiratory tract infection due to human metapneumovirus in a long‐term care facility. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1152‐1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Poritz MA, Blaschke AJ, Byington CL, et al. FilmArray, an automated nested multiplex PCR system for multi‐pathogen detection: development and application to respiratory tract infection [serial online]. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Williams JV, Martino R, Rabella N, et al. A prospective study comparing human metapneumovirus with other respiratory viruses in adults with hematologic malignancies and respiratory tract infections. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1061‐1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kamboj M, Gerbin M, Huang CK, et al. Clinical characterization of human metapneumovirus infection among patients with cancer. J Infect. 2008;57:464‐471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Srinivasan A, Gu Z, Smith T, et al. Prospective detection of respiratory pathogens in symptomatic children with cancer. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32:e99‐e104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Martino R, Porras RP, Rabella N, et al. Prospective study of the incidence, clinical features, and outcome of symptomatic upper and lower respiratory tract infections by respiratory viruses in adult recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplants for hematologic malignancies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11:781‐796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Englund JA, Boeckh M, Kuypers J, et al. Brief communication: fatal human metapneumovirus infection in stem‐cell transplant recipients. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:344‐349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shah DP, Shah PK, Azzi JM, El Chaer F, Chemaly RF. Human metapneumovirus infections in hematopoietic cell transplant recipients and hematologic malignancy patients: a systematic review. Cancer Lett. 2016;379:100‐106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wyde PR, Chetty SN, Jewell AM, Boivin G, Piedra PA. Comparison of the inhibition of human metapneumovirus and respiratory syncytial virus by ribavirin and immune serum globulin in vitro. Antiviral Res. 2003;60:51‐59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hamelin ME, Prince GA, Boivin G. Effect of ribavirin and glucocorticoid treatment in a mouse model of human metapneumovirus infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:774‐777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Park SY, Baek S, Lee SO, et al. Efficacy of oral ribavirin in hematologic disease patients with paramyxovirus infection: analytic strategy using propensity scores. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:983‐989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shachor‐Meyouhas Y, Ben‐Barak A, Kassis I. Treatment with oral ribavirin and IVIG of severe human metapneumovirus pneumonia (HMPV) in immune compromised child. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57:350‐351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Egli A, Bucher C, Dumoulin A, et al. Human metapneumovirus infection after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Infection. 2012;40:677‐684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hirsch HH, Martino R, Ward KN, Boeckh M, Einsele H, Ljungman P. Fourth European Conference on Infections in Leukaemia (ECIL‐4): guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of human respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza virus, metapneumovirus, rhinovirus, and coronavirus. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:258‐266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Outbreaks of human metapneumovirus in 2 skilled nursing facilities—West Virginia and Idaho, 2011‐2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:909‐913. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Peiris JS, Tang WH, Chan KH, et al. Children with respiratory disease associated with metapneumovirus in Hong Kong. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:628‐633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Renaud C, Campbell AP. Changing epidemiology of respiratory viral infections in hematopoietic cell transplant recipients and solid organ transplant recipients. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:333‐343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chemaly RF, Shah DP, Boeckh MJ. Management of respiratory viral infections in hematopoietic cell transplant recipients and patients with hematologic malignancies. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(suppl 5):S344‐S351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Waghmare A, Campbell AP, Xie H, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus lower respiratory disease in hematopoietic cell transplant recipients: viral RNA detection in blood, antiviral treatment, and clinical outcomes. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:1731‐1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chemaly RF, Hanmod SS, Rathod DB, et al. The characteristics and outcomes of parainfluenza virus infections in 200 patients with leukemia or recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2012;119:2738‐2745; quiz 2969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Perkins JG, Flynn JM, Howard RS, Byrd JC. Frequency and type of serious infections in fludarabine‐refractory B‐cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia and small lymphocytic lymphoma: implications for clinical trials in this patient population. Cancer. 2002;94:2033‐2039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Molteni A, Nosari A, Montillo M, Cafro A, Klersy C, Morra E. Multiple lines of chemotherapy are the main risk factor for severe infections in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia with febrile episodes. Haematologica. 2005;90:1145‐1147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Oliveira R, Machado A, Tateno A, Boas LV, Pannuti C, Machado C. Frequency of human metapneumovirus infection in hematopoietic SCT recipients during 3 consecutive years. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;42:265‐269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ali M, Baker JM, Richardson SE, Weitzman S, Allen U, Abla O. Human metapneumovirus (hMPV) infection in children with cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2013;35:444‐446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shah DP, Ghantoji SS, Ariza‐Heredia EJ, et al. Immunodeficiency scoring index to predict poor outcomes in hematopoietic cell transplant recipients with RSV infections. Blood. 2014;123:3263‐3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shah DP, Ghantoji SS, Mulanovich VE, Ariza‐Heredia EJ, Chemaly RF. Management of respiratory viral infections in hematopoietic cell transplant recipients. Am J Blood Res. 2012;2:203‐218. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shah JN, Chemaly RF. Management of RSV infections in adult recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2011;117:2755‐2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bonney D, Razali H, Turner A, Will A. Successful treatment of human metapneumovirus pneumonia using combination therapy with intravenous ribavirin and immune globulin. Br J Haematol. 2009;145:667‐669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hofmeyr A, Dunlop L, Ling S, Fiakos E, Maley M. Ribavirin treatment for human metapneumovirus and methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus co‐infection in adult haematological malignancy [abstract]. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:S812. Abstract R2697. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shahda S, Carlos WG, Kiel PJ, Khan BA, Hage CA. The human metapneumovirus: a case series and review of the literature. Transpl Infect Dis. 2011;13:324‐328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Visentin A, Compagno N, Cinetto F, et al. Clinical profile associated with infections in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Protective role of immunoglobulin replacement therapy. Haematologica. 2015;100:e515‐e518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Seo S, Gooley T, Kuypers HM, et al. Human metapneumovirus infections in hematopoietic cell transplant recipients: seasonality and factors associated with progression to lower respiratory tract disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(suppl):S110‐S111. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bosis S, Esposito S, Osterhaus AD, et al. Association between high nasopharyngeal viral load and disease severity in children with human metapneumovirus infection. J Clin Virol. 2008;42:286‐290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Martin ET, Kuypers J, Heugel J, Englund JA. Clinical disease and viral load in children infected with respiratory syncytial virus or human metapneumovirus. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;62:382‐388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Papenburg J, Hamelin M, Ouhoummane N, et al. Comparison of risk factors for human metapneumovirus and respiratory syncytial virus disease severity in young children. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:178‐189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vicente D, Montes M, Cilla G, Perez‐Yarza EG, Perez‐Trallero E. Differences in clinical severity between genotype A and genotype B human metapneumovirus infection in children. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:e111‐e113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]