Abstract

Empathy can be defined as a social interaction skill that consists of four components: (1) a statement voiced in the (2) appropriate intonation, accompanied by a (3) facial expression and (4) gesture that correspond to the affect of another individual. A multiple-baseline across response categories experimental design was used to evaluate the effectiveness of a prompt sequence (video modeling, in vivo modeling, manual and verbal prompting) and reinforcement to increase the frequency of complex empathetic responding by four children with autism. The number of complex empathetic responses increased systematically with the successive introduction of the treatment package. Additionally, generalization was demonstrated to untaught stimuli and a novel adult. Responding maintained over time to varying degrees for all participants. The data illustrate that children with autism can be taught using modeling, prompting, and reinforcement to discriminate between categories of affective stimuli and differentially respond with complex empathetic responses.

Keywords: Autism, Empathy, Social skills, Adolescents, Discrimination, Complex responding

Introduction

Empathy may be regarded as vicariously feeling what another person feels as a result of an event that they have experienced (Wondra and Ellsworth, 2015). This explanation proves problematic for behavior analysis because we cannot directly observe another’s emotions. Without direct observation, we cannot determine whether a person is actually feeling what another person is feeling. We may record reports of how people say they feel, but those are simply recordings of verbal behavior as opposed to the behavior itself. Instead, we rely on the observable emotional behavior of another person, their affect, to determine that they are indeed being empathetic towards us. While their actual feelings are unknown, their overt behavior suggests the presence of the covert response. A definition of empathy that focuses on affect and allows behavior analysts to study the topic can be presented as differentially responding to the affective stimulus of another with a corresponding affective stimulus. This definition suggests that behavior analysts can successfully study empathy by observing an individual’s affective behavior and manipulating the affective behavior of a conversation partner. Furthermore, we can increase the perception of empathy in those for whom it is deficient by increasing the occurrence of affective responses associated with it.

Previous authors have described empathy as a social interaction skill that includes both verbal and non-verbal affective components. Tepper and Haase (1978) suggested that intonational features of a statement play an important role in how others may interpret them. Gena, Krantz, McClannahan, and Poulson (1996) identified empathy as consisting of three components: a verbal statement, a contextually appropriate facial expression, and a gesture that corresponds to the affect displayed. Buffington, Krantz, McClannahan, and Poulson (1998) included gestures and verbal statements in their discussion of empathetic responses and Daou, Vener, and Poulson (2014) discuss the importance of appropriate statements, intonation, and facial expressions for sustainable social interactions. Synthesizing conclusions from these articles, empathy can be described as a social interaction skill consisting of four components: (1) a verbal statement uttered in the correct (2) intonation accompanied by an appropriate (3) facial expression and a (4) gesture corresponding to the affect displayed. The absence of one of these four components may result in a subjective interpretation of an inappropriate response. For example, if you excitedly tell me that you have just received a promotion, an expected response might be to give me a hug and say, “That’s Fantastic! Congratulations!” in an excited tone of voice while smiling. If that same statement is voiced monotonically or with a descending tone and you are not smiling, the response may be considered insincere or disingenuous even if you truly mean it.

With a behavioral definition of empathy identified that includes accepted affective components from previous literature, we can identify possible reasons why we possess empathy. Seyfarth and Cheney (2013) suggest that from an evolutionary perspective, empathy may lead to imitation and predictability among others that facilitates strong social bonds and can lead to reproduction. From a behavioral perspective, we may hypothesize that empathy functions to provide conditioned social reinforcement in the form of non-verbal stimuli (e.g., smiles) or positive verbal interactions. Neurotypically developing individuals may learn to engage in empathetic responses because empathy helps to facilitate and maintain social interaction. Results from Poulson (1983), Pelaez, Virues-Ortega, and Gewirtz (2011), and Hirsh, Stockwell, and Walker (2014) support this hypothesis.

In her study, Poulson (1983) presented social reinforcement under two schedules: continuous or differential reinforcement of other-than-vocalizations. As such, infants either obtained social reinforcement continuously or for not engaging in vocalizations. Her results showed that infants vocalized systematically more during the continuous schedule compared to the DRO condition illustrating that the vocal behavior of infants as young as 2 ½ months old are receptive to behavioral contingencies using social interaction as reinforcement. Additionally, Palaez et al. (2011) and Hirsh et al. (2014) used a contingent parental imitation as a form of social reinforcement for the vocal behavior of 3–12-month-old infants. Both studies showed greater rates of vocalizations during contingent reinforcement compared to yoked conditions concluding that social reinforcement can serve to reinforce infant behavior.

While empathy is evident in most neurotypically developing individuals, it is absent in many with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) (Charman et al., 1997, Sigman, Kasari, Kwon, & Yirmiya, 1992). One argument for this deficit might be that individuals with ASD are not sensitive to contingencies of social reinforcement due to the core deficits associated with the disorders. While this may be the case in some individuals with ASD, social attention can serve as reinforcement for the behavior of individuals with developmental disabilities and ASD (Iwata, Dorsey, Slifer, Bauman, & Richman, 1994). Therefore, if some individuals with ASD are sensitive to social reinforcement, the absence of empathetic responding may instead be due to an inability to identify the salient aspects of affective responses that should evoke the empathetic response. However, Argott, Townsend, Sturmey, and Poulson (2008) successfully taught adolescents with ASD to discriminate and differentially respond to affective stimuli that consisted of a facial expression and a gesture with an appropriate empathetic response. In their study, Argott et al. used a script-fading procedure to teach appropriate empathetic verbal responses to non-vocal affective stimuli from three categories: joy, frustration, and pain. As such, participants were required to discriminate potentially less salient aspects of an affective stimulus and emit an appropriate empathetic statement. The results suggest that individuals with ASD may be able to identify and discriminate between the necessary characteristics of affective stimuli. Consequently, reduced empathetic behavior by individuals with ASD may instead be due to untaught relations between affective stimuli and appropriate empathetic responses as has been suggested by Gena et al. (1996).

Interventions addressing empathetic responding in ASD are not a well-researched area; however, a handful of previous researchers have addressed separate components of the empathetic response using behavioral interventions. In one of the first empirical studies on this topic, Gena et al. (1996) successfully increased the use of contextually appropriate verbal statements, facial expressions, and gestures by youths with ASD. In that study, participants with ASD were provided reinforcement for emitting a contextually appropriate response that matched the affect of a brief stimulus presented by the experimenter. Modeling and verbal prompting procedures were used as error correction if participants did not independently emit an appropriate response. The procedures resulted in the participants’ use of contextually appropriate affective responses that generalized to untaught stimuli and settings. Gena, Couloura, and Kymissis (2005) extended upon and received similar results as Gena et al. (1996) by teaching similar responses using similar procedures but also compared the use of in vivo and video modeling procedures as error correc-tion procedures. The results from Gena et al. (2005) suggested that both types of models were equally effective error--correction procedures to teach affective responses and might be able to be used interchangeably with individuals with ASD in these circumstances.

Building upon Gena et al. (1996), Buffington et al. (1998) taught children with ASD to differentially respond using gestures and verbal statements. Similar to Gena et al. (1996), experimenters provided reinforcement for appropriate affective responses and used an error correction procedure of modeling and physical/verbal prompting procedures if the participants did not emit the correct response. These procedures also increased appropriate affective responding that generalized to untaught stimuli and settings. Additionally, as previously discussed, Argott et al. (2008) incorporated the use of reinforcement and a script-fading procedure to increase the use of appropriate empathetic statements to affective motor discriminative stimuli. Likewise, Schrandt, Townsend, and Poulson (2009) incorporated a prompt-delay procedure using modeling and prompting to teach 4–6-year-old children with ASD to use empathetic statements and gestures towards puppets. In each of these studies, the participants were able to differentially respond to affective stimuli using appropriate empathetic responses.

Directly extending the research of Gena and her colleagues (1996, 2005), and building upon the research conducted by Argott et al. (2008) and Schrandt, et al. (2009), Daou et al. (2014) effectively increased the use of a more complex empathetic response that included statements, appropriate intonation, and facial expressions in three 9–13-year-old youths with ASD. Once again, reinforcement was provided for the appropriate use of the various components of the empathetic response with modeling and prompting used to teach the skills, Similar to Argott et al. (2008) and Schrandt et al. (2009), Daou and colleagues used errorless teaching procedures and systematically faded prompts as participants began to respond independently. Additionally, they used a script-fading procedure to teach the verbal statements associated with each category of affect and a shaping procedure to reinforce appropriate facial expressions. Similar to the previous studies, responding increased to trained and untrained stimuli, but also maintained during follow-up sessions conducted 1 ½–6 months after the conclusion of treatment.

The previous studies suggest that empathetic responding can be addressed using the operant techniques of differential reinforcement, modeling, and prompting. Each study successfully teaches one or more components of an empathetic response; however, to date, researchers have not attempted to teach an empathetic response that consists of the four previously discussed components (statement, intonation, facial expression, gesture) simultaneously.

Given that researchers have found that many individuals with autism do not engage in empathetic responding and the few articles that report successful methods to address these deficits do so in isolated or incomplete units, the purpose of the current study was (1) to extend the current research on empathy and affective responding by individuals with ASD by teaching the separate components of the empathetic response collectively as complex empathetic responses using proven behavioral procedures and (2) to promote generalization of the complex response to untaught stimuli within the same affective categories, untaught individuals, and across time by testing the presence of the response after a specific time interval. Complex empathetic responses consisted of four components that were required for the response to be considered correct: (1) verbal statements in the (2) appropriate intonation, (3) contextually appropriate facial expressions, and (4) gestures corresponding to the affect displayed.

Method

Participants and Setting

Four 10–12-year-old young adolescents previously diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder by a licensed independent practitioner in New Jersey participated in the study. Each participant attended a private, educational program that offered center and home-based behavioral interventions for individuals on the autism spectrum for a minimum of 6 years prior to the start of the study. Center-based programming occurred approximately 5.5 h per day, 5 days per week, and home-based services occurred after school hours. Participants were identified for inclusion in the study through anecdotal reports from teachers and the program director that they did not show empathy towards other individuals. Each participant engaged in minimal stereotypic or disruptive behavior, had experience with token and point-based reinforcement systems, and had experience acquiring skills using modeling and prompting procedures. Each participant could vocally respond to questions using 3–6 word statements and would often greet new individuals upon seeing them for the first time, but would only periodically emit spontaneous verbalizations outside of those situations.

During all sessions, participants and their instructor met the experimenter in an unoccupied classroom within the educational program. All sessions were video recorded to score inter-observer agreement. The classroom was relatively empty with the exception of a 19″ television equipped with a DVD player that was used to present video models, a u-shaped table where stimulus materials were laid, empty shelves, and chairs. The participant, his/her instructor, and the experimenter were the only individuals who occupied the classroom during experimental sessions.

Experimental Design and Dependent Variables

A multiple-baseline-across-response category experimental design was used to evaluate the treatment procedure. The categories included were joy, frustration, and pain, and the order of presentation of each category was counterbalanced across participants. The dependent variables were cluster responses that were scored as correct if the participant (a) directed their gaze in the direction of the instructor, (b) responded within 5 s of the presentation of the affective stimulus, and (c) emitted an empathetic response that corresponded to the affect displayed by the instructor and included four components (see Table 1). Characteristics of the components were selected through self-observation and observation of typical individuals responding during similar situations. All four components of the empathetic responses were necessary for the response to be scored correct. If any component of the response was missing or incorrect, the entire response was scored as incorrect. Facial expressions in the pain category varied between participants because the experimenter could not evoke downturned eyebrows for Jared and George in any context.

Table 1.

Empathetic responses taught in response to affective stimuli

| Category of affect | Statements of empathy | Appropriate gesture | Facial expression | Appropriate intonation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joy | That’s great! That’s awesome! |

Give a high five | Smile | High pitch Lively intonation |

| Frustration | Can I help you? Let me help? |

Place hand on chest with palm facing body | Raised eyebrows | Rising pitch |

| Pain | Can I get you something? Do you need anything? |

Hold one hand out with palm up | Lowered (Derek & Janine) or Raised (Jared & George) eyebrows |

Low pitch Sad intonation |

Procedure

Participants sat next to the table with their instructor sitting approximately 1 m across from them. Across all conditions, trials included the instructor presenting an affective stimulus, the presentation of a consequence according to the condition in effect (defined in each section below), the experimenter (first author) recording the participant’s response, and an approximate inter-trial interval of 5 s. After the inter-trial interval, the next trial was initiated. The length of each trial varied dependent on the condition and the amount of prompting required per trial. Affective stimuli consisted of the instructor’s live facial expression, gesture, and statement in an intonation that corresponded to a category of affect. Table 2 includes sample affective stimuli.

Table 2.

Sample affective stimuli presented by the instructor

| Category/facial expression | Gesture | Script |

|---|---|---|

| Joy/smile | -Hold up the puzzle -Raise arms above head -Hold up the hot wheels -Hold up and point to play-do -Raise arms above head |

-I finished my puzzle! -I won the game! (electronic card game) -I found my toy -Look what I made! -I figured it out! (rubix cube) |

| Frustration/angry | -Struggle with a bottle -Bang fly wheels on table -Struggle with k’nex -Point to the word ‘the’ -Try to remove Tupperware top |

-I cannot open it -This will not work -This will not fit -I cannot read the word -It is stuck |

| Pain/sad | -Right hand on right side of head -Rub lower back -Rub right cheek -Rub back of neck -Bump knee on chair |

-I have such a headache -My back really hurts -I have a toothache -My neck is so sore -Owww |

Throughout the study, instructors presented participants with 12 trials associated with each of three affective categories per session. Nine of the 12 stimuli in each category were allocated for training while the remaining three stimuli were used to probe for generalization across stimuli. In total, sessions consisted of 36 successive trials (27 training trials plus 9 generalization probes), lasted approximately 25 min, and occurred 5 days a week.

Baseline

The instructor responded to a contextually appropriate response emitted by the participant with a natural social statement. For example, if the instructor said, “I can’t read the word,” and the participant responded with, “Let me help,” the instructor said “thank you” and allowed the participant to help. Incorrect responses or non-responding terminated the trial. The experimenter provided reinforcement contingent on attending to the instructor on a VR2 schedule of reinforcement.

Prompting and Reinforcement

The experimenter delivered behavior-specific praise and tokens contingent on empathetic responses that included all four components (statement, intonation, gesture, and facial expression) to the affective stimulus presented by the instructor within 5 s. During the first leg of the multiple-baseline design when one category of affect was in intervention, the experimenter also delivered tokens for attending during baseline trials on a VR 2 schedule to maintain the rate of reinforcement experienced during baseline. The VR 2 schedule was discontinued once intervention was implemented for the second category of affect.

All incorrect responses, including those that did not include all four components, resulted in a prompt sequence progressing from video modeling to in vivo modeling, then manual and verbal prompting. During each prompt level, prompts were provided for every component of the empathetic response, regardless of whether the participant correctly emitted a specific component. Additionally, the instructor re-presented the affective stimulus after each prompt to provide the participant an opportunity to respond correctly to the affective stimulus. If the participant responded incorrectly to the affective stimulus, or did not respond to the provided prompt, the next prompt level in the sequence was initiated. This occurred until the participant emitted an independent empathetic response to the affective stimulus.

When an incorrect response occurred, the experimenter initially prompted the correct response by presenting a video model of the expected empathetic response. The video model was 2–3 s in duration and displayed the experimenter modeling one of two appropriate verbal responses in the proper intonation with a corresponding gesture and facial expression. If the participant did not respond to the video model within 5 s or responded incorrectly to the re-presented affective stimulus, the experimenter presented an in vivo model. The in vivo model was identical to the video model with the exception that it was presented live to the participant. If the participant did not respond to the in vivo model within 5 s or responded incorrectly to the re-presented affective stimulus again, the experimenter manually guided the participant’s hands to engage in the gesture and their faces to emit the appropriate facial expression. Additionally, the experimenter provided a verbal model of one of the two appropriate statements in the proper intonation. For example, this step of the correction procedure for a stimulus requiring a response from the joy category would include the experimenter manually guiding the participant’s hand to give a high five while manually prompting a smile and saying, “say ‘That’s great!’” (this final prompting step was always successful in promoting the empathetic response). Then, the instructor re-presented the affective stimulus and provided praise and token reinforcement for the correct empathetic response. Because of this procedure, reinforcement never followed a prompted response and only followed an unprompted empathetic response to the affective stimuli.

Generalization

Three stimuli from each category of affect (9 total) were randomly designated as generalization probes with the exception that no two participants could have the same generalization probe. Probe trials were interspersed among training trials throughout all sessions. Generalization across individuals was assessed once a week with a novel adult presenting all training and generalizations affective stimuli. Baseline procedures were followed during all generalization trials.

Maintenance

Observers collected follow-up data 6 weeks after the participant met an exit criterion of two consecutive days of responding to at least 89% of empathetic responses per category. No instruction or prompting procedures were provided during the 6-week period between the final data point and follow-up. Procedures were identical to those in baseline.

Analysis

Observers collected data on each component of the empathetic response and scored an occurrence of an empathetic response if every component was correctly emitted as defined above. Figures display data on the occurrence of correct empathetic responses that include all four components. Component data are available from the first author upon request. Interobserver agreement (IOA) on the empathetic response was measured live and from videotapes of sessions, and agreements were defined as both observers recording a trial with a complete empathetic response as occurring or not. Disagreements were defined as one observer scoring an occurrence of a complete empathetic response while the other scored the non-occurrence of a complete response on the same trial. IOA was calculated by dividing the total number of agreements by the total number of agreements plus disagreements and multiplying by 100. Across all participants, IOA was recorded during 37% of all sessions and averaged 96% (range 33%), 97% (range 42%), and 98% (range 33%) agreement for stimuli from the joy, frustration, and pain categories, respectively.

Observers also collected data on the integrity of the independent variable consisting of the following components: eye contact, the accurate presentation of the affective stimulus, the contingent presentation of token reinforcement, contingent presentation of the video model, live model, and manual prompts, and the accurate re-presentation of the affective stimulus. The mean percentage of components presented accurately was calculated as 97.5%. IOA was also calculated on the integrity of the independent variable by scoring agreement for each component of the treatment procedure. Mean agreement across all participants was calculated as 98%.

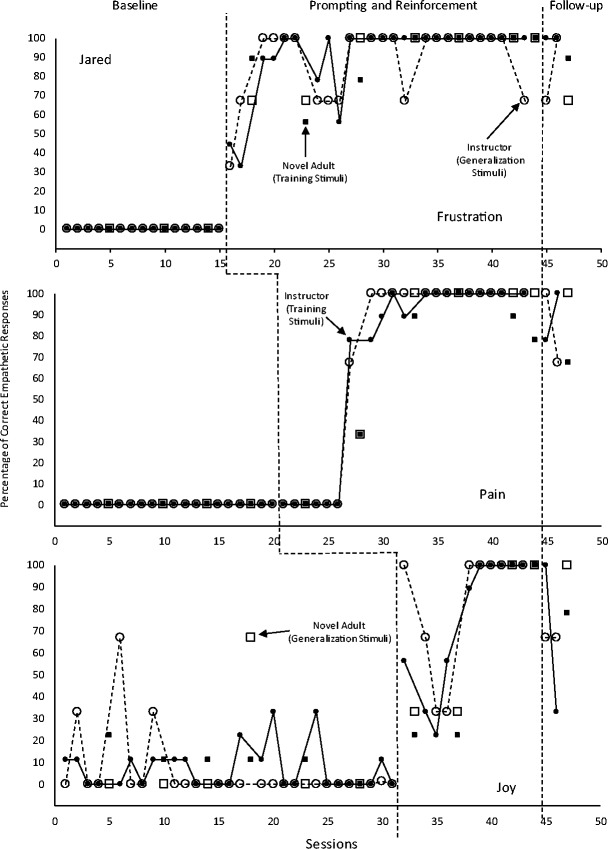

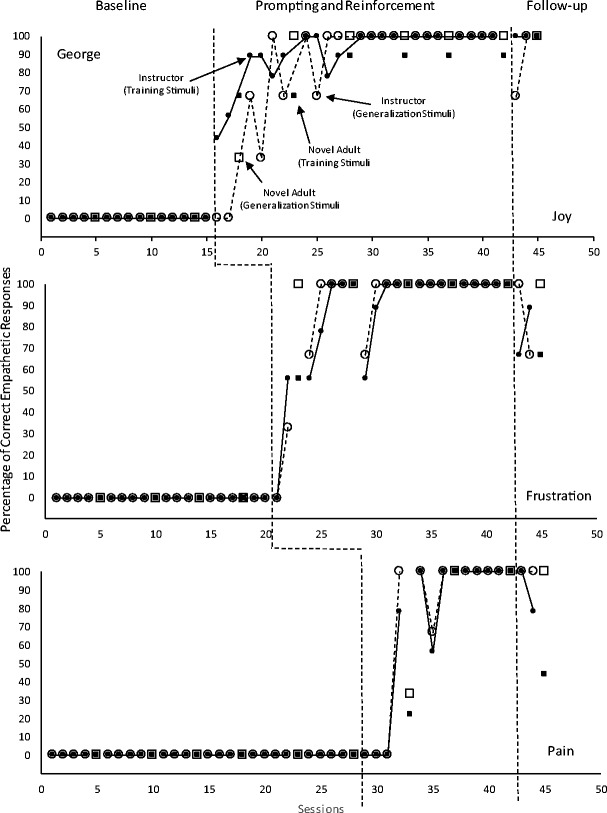

Results

The number of correct empathetic responses to affective stimuli is displayed for each participant in Figs. 1–4. All participants displayed similar patterns of responding during the study; therefore, results are discussed in general terms. During baseline, all participants, except Jared, did not display complex empathetic responses across any categories of affect. Jared displayed inconsistent levels of correct responding to stimuli from the joy category but did not respond with complex responses to either the pain or frustration category. With the systematic introduction of the intervention, all four participants developed complex responding to affective stimuli across all three categories of affect increasing their percentage of correct responding from 0–100% correct responses per session. Moreover, the participants successfully generalized the use of those complex empathetic responses to untrained stimuli and novel adults that were never associated with training or token reinforcement with data increasing along with those from training stimuli. Furthermore, correct responding remained above baseline levels during follow-up testing, however, did decrease relative to intervention sessions. Data for Janine followed the same general pattern; however, due to time constraints, consent to participate was rescinded and she only completed the first two categories of affect, and intervention was not implemented for the pain category. Nevertheless, there was a systematic increase in responding with complex empathetic responses to training and generalization stimuli with the instructor and a new adult with the introduction of the intervention.

Fig. 2.

Percentage of correct empathetic responses to training and generalization stimuli across sessions for Derek. Closed symbols represent responding to training stimuli. Open symbols represent responding to generalization stimuli. Circles represent responding to the instructor, and squares represent responding to the novel adult

Fig. 3.

Percentage of correct empathetic responses to training and generalization stimuli across sessions for Jared. Closed symbols represent responding to training stimuli. Open symbols represent responding to generalization stimuli. Circles represent responding to the instructor, and squares represent responding to the novel adult

Fig. 1.

Percentage of correct empathetic responses to training and generalization stimuli across sessions for George. Closed symbols represent responding to training stimuli. Open symbols represent responding to generalization stimuli. Circles represent responding to the instructor, and squares represent responding to the novel adult

Fig. 4.

Percentage of correct empathetic responses to training and generalization stimuli across sessions for Janine. Closed symbols represent responding to training stimuli. Open symbols represent responding to generalization stimuli. Circles represent responding to the instructor, and squares represent responding to the novel adult

Social validity was assessed by asking 17 graduate students in psychology from a College in northern New Jersey to rate 18 video clips randomly selected from the first three sessions of baseline and the final three sessions of treatment on a 5-point likert scale with one representing no empathy and five representing typically expected empathy. The mean rating was 2.7 for clips from baseline sessions and 4.3 for clips from treatment sessions. A repeated measures ANOVA resulted in a significant difference, t (16) = 5.04, (p < .01) between the two conditions suggesting responses at the end treatment were more appropriate than those during baseline.

Discussion

Individuals with autism frequently display deficits in empathy and other social skills. Participants in the current study were taught to discriminate between three categories of affect (joy, frustration, and pain) and respond with a complex empathetic response that consisted of an appropriate verbal statement voiced in the correct intonation, using an appropriate gesture, and a facial expression that corresponded the affect displayed by conversation partner. Data from the current study are consistent with previous research teaching individuals with autism various units of empathetic responding (e.g., Gena et al., 1996; Buffington et al., 1998; Schrandt et al., 2009; Argott et al., 2008) and extend the previous research by teaching those units collectively.

An interesting finding from the current study is that adolescents with autism can not only learn to discriminate and respond to stimuli that are explicitly trained but can generalize those skills to stimuli from the same class and to other individuals that are not associated with intervention. These results are consistent with those from previous research (Genal et al., 1996; Buffington et al., 1998). Responding to stimuli not associated with intervention suggests that the participants were responding to some common aspect of the stimuli from the affective class. Additionally, responding that maintained above baseline levels during follow-up testing suggest that the complex responses became part of each participant’s behavioral repertoires.

The majority of trials (86%) that were not scored as correct during follow-up sessions can be attributed to the omission of the appropriate facial expression during those trials. Generally, participants emitted the correct statement, intonation, and gesture, but either omitted or inaccurately displayed the necessary facial expression. In addition to this observation, manual prompts were often necessary to teach the facial expressions during training trials, and the experimenter could not evoke the originally planned facial expressions for the pain category from Jared and George. As such, the facial expression component of the empathetic response would likely benefit from prior teaching before its inclusion in a package that requires the complex empathetic response. Nevertheless, participants learned the simplified facial expressions used in this study while the treatment package was in effect and continued to use them, although inconsistently, during follow-up, supporting their inclusion in this study.

While preliminary, the social validity ratings suggest that all the components of the empathetic response appeared typical. These findings dispute previous research that has noted that the facial expressions emitted by individuals with ASD often appear mechanical (Loveland et al., 1994). One possible explanation for the difference is that the facial expression was not isolated in the present research. Requiring participants to emit appropriate vocal intonation as well as make the correct statement and gesture along with the facial expression might have aided the participants in emitting natural facial expressions. Perhaps emitting a mechanical facial expression and the appropriate intonation are incompatible responses. Further, social validity measures should compare the empathetic response used in this study to empathetic responses that include appropriate statements alone. Additionally, future measures of social validity should include raters with a greater expertise in empathetic responding and autism.

The current study has two important implications for practice. First, this study suggests that individuals with ASD can discriminate between relatively subtle stimuli. While the joy category was clearly different from the other categories included in this study, affective stimuli associated with frustration and pain are relatively similar. Overall, the participants reliably discriminated between stimuli from three categories of affect and emitted different responses that were associated with each. The importance of this finding cannot be overstated. Due to stimulus over-selectivity, individuals with ASD may attend to potentially irrelevant aspects of a stimulus that are more salient to them (Leader, Loughnane, McMoreland, & Reed, 2009). As a result, when developing training stimuli for individuals with ASD, interventionists may manipulate the characteristics that should hold stimulus control to make sure that those characteristics more salient. For example, when teaching children with ASD to identify objects in pictures, it is often ideal to ensure that the backgrounds are plain white. This manipulation eliminates the possibility that an irrelevant stimulus in the background can exert stimulus control over responding. These modifications are often necessary as individuals are entering intervention and developing early skills; however, as foundational skills are developed, the necessity for increased saliency may be diminished. The participants in the current study can be described as having those foundational skills which may have facilitated the acquisition of the required discriminations.

The second important implication is that adolescents with autism can learn complex empathetic responses that include multiple components and can generalize those responses to untaught stimuli and people. While previous research has successfully taught individuals with ASD different aspects of an empathetic response, the emission of those components without the others may result in a response that is judged to be inappropriate or insincere. Moreover, while there is not a direct comparison, it is likely that the amount of time required to teach the components separately would be extensive. Teaching the entire complex response at once reduces the overall amount of time required to teach the skill leaving time to teach other necessary social or academic skills.

It would be interesting for future researchers to conduct a component analysis of the treatment package and the affective stimuli. While there are no data to suggest it, informal observations suggest that the video model may have affected only the desired verbal statements of empathy, the in vivo model appeared to be needed to affect the vocal inflection of the statement and the gesture, while manual prompts seemed necessary to teach the facial expression. These conjectures raise a question as to the necessity of the video model itself and whether the results would have been similar if the video model had been removed. Results of an investigation may suggest the video model served as a non-intrusive prompt once all components were initially taught. It would be equally interesting to analyze whether participants engaged in complex or simple discrimination of the affective stimulus focusing on one or all of the presented components.

Further research is also needed to evaluate procedures to facilitate generative language and the effectiveness of this procedure on affective categories not included in this study. The three categories of affect included in the current study required participants to discriminate between a relatively small set of categories. It would be interesting to evaluate whether individuals with ASD would be able to discriminate other categories that were more similar than those included, such as frustration and anger. The current participants initially produced novel responding. However, these novel responses did not endure, even though they resulted in reinforcement when they were included in an empathetic response. Future replications may include more verbal responses, or other procedures designed to increase generative language. Finally, this study did not include a measure of participant responding to peers presenting the affective stimuli. Those data would be necessary to consider this intervention wholly successful.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the families, students, and teachers whose hard work made this research possible. We would also like to thank our colleagues whose feedback was immeasurable.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Statement of Human Rights

ᅟ

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants or their guardians included in this study.

Footnotes

• Children with autism can learn to discriminate between affective stimuli from three categories

• Complex empathetic responses can be learned by children with autism

• Complex empathetic responses generalize to untaught stimuli and individuals

• Prompting and reinforcement can effectively be used to teach empathetic skills

References

- Argott PJ, Townsend DB, Sturmey P, Poulson CL. Increasing the use of empathetic statements in the presence of a non-verbal affective stimulus in adolescents with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2008;2:341–352. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2007.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buffington DM, Krantz PJ, McClannahan LE, Poulson CL. Procedures for teaching appropriate gestural communication skills to children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1998;28:535–545. doi: 10.1023/A:1026056229214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charman T, Swettenham J, Baron-Cohen S, Cox A, Baird G, Drew A. Infants with autism: an investigation on empathy, pretend play, joint attention, and imitation. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:781–789. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.33.5.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daou N, Vener SM, Poulson CL. Analysis of three components of affective behavior in children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2014;8:480–501. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2014.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gena A, Couloura S, Kymissis E. Modifying the affective behavior of preschoolers with autism using in-vivo or video modeling and reinforcement contingencies. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2005;35:545–556. doi: 10.1007/s10803-005-0014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gena A, Krantz PJ, McClannahan LE, Poulson CL. Training and generalization of affective behavior displayed by youth with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1996;29:291–304. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh JL, Stockwell F, Walker D. The effects of contingent caregiver imitation of infant vocalizations: a comparison of multiple caregivers. Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2014;30:20–28. doi: 10.1007/s40616-014-0008-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata BA, Dorsey MF, Slifer KJ, Bauman KE, Richman GS. Toward a functional analysis of self-injury. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:197–209. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leader G, Loughanne A, McMoreland C, Reed P. The effect of stimulus salience on over-selectivity. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009;39:330–338. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0626-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loveland KA, Tunali-Kotoski B, Pearson DA, Brelsford KA, Ortegon J, Chen R. Imitation and expression of facial affect in autism. Development and Psychopathology. 1994;6:433–444. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400006039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelaez M, Virues-Ortega J, Gewirtz JL. Reinforcement of vocalizations through contingent vocal imitation. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2011;44:33–40. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulson CL. Differential reinforcement of other-than-vocalizations as a control procedure in the conditioning of infant vocalization rate. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1983;36:471–489. doi: 10.1016/0022-0965(83)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrandt JS, Townsend DB, Poulson CL. Teaching empathy skills to children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2009;42:17–32. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2009.42-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyfarth, R. M. & Cheney, D. L. (2013). Affiliation, empathy, and the origins of theory or mind. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110, 10349–10356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sigman MD, Kasari C, Kwon JH, Yirmiya N. Response to the negative emotions of others by autistic, mentally retarded, and normal children. Child Development. 1992;63:796–807. doi: 10.2307/1131234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepper DT, Haase RF. Verbal and nonverbal communication of facilitative conditions. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1978;25:35–44. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.25.1.35. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wondra JD, Ellsworth PC. An appraisal theory of emotion and other vicarious emotional experiences. Psychological Review. 2015;122(3):411–428. doi: 10.1037/a0039252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]