Abstract

The objective of the study reported here was to determine the onset, duration, and degree of analgesia achieved with a combination of romifidine (50 μg/kg body weight [BW]) and morphine (0.1 mg/kg BW) administered epidurally. Ten adult Holstein Friesen cows were assigned to either a treatment group receiving the romifidine and morphine combination or a control group receiving 0.9% saline in a randomized, blinded, crossover design. Cows were assessed for degree of flank analgesia and systemic sedation at various time intervals over a period of 24 hours. The romifidine and morphine combination, compared with saline, provided significant analgesia for at least 10 minutes (P = 0.016) and up to 12 hours (P = 0.004) after epidural administration. Treated cows were sedate between 10 minutes (P = 0.016) and 6 hours (P = 0.002) after epidural administration. These results provide evidence for a potential cost-effective intra- and postoperative method of analgesia; however, the sedation seen in this study could be detrimental to patients expected return to the farm shortly after surgery. Further research into withdrawal times, systemic effects, and potential adverse effects are needed before an opiod and α2-adrenergic agonist combination can be used safely in a clinical setting

Abstract

Résumé — Association de romifidine et de morphine lors de l’analgésie épidurale du flanc chez les bovins. L’objectif de cette étude était de déterminer le début, la durée et le degré d’analgésie obtenue par l’association romifidine [50 μg/k de poids corporel (PC)] et de morphine (0,1 mg/kg PC) administrée par voie épidurale. Dix vaches Holstein Friesian ont été assignées soit au groupe traité recevant romifidine et morphine, soit au groupe témoin recevant 0,9 % de saline, dans une étude croisée à l’aveugle et randomisée. Les vaches ont été évaluées pour le degré d’analgésie du flanc et la sédation systémique à différents intervalles de temps sur une période de 24 heures. Lorsque comparée à la saline, l’association romifidine-morphine provoquait une analgésie significative pour au moins 10 minutes (P = 0,016) et jusqu’à 12 h (P = 0,004) après administration épidurale. Les vaches traitées étaient sous sédation entre 10 minutes (P = 0,016) et 6 heures (P = 0,002) après administration épidurale. Ces résultats fournissent une preuve qu’il s’agit d’une méthode d’analgésie intra et postopératoire efficace et peu dispendieuse; cependant, la sédation observée au cours de cette étude peut être nuisible pour les patients devant retourner à la ferme peu après la chirurgie. De nouvelles recherches sur les temps de retrait, les effets systémiques et les effets indésirables potentiels sont nécessaires avant que l’association d’un opioïde et d’un agoniste α2 adrénergique puisse être utilisée de façon sécuritaire dans un environnement clinique.

(Traduit par Docteur André Blouin)

Introduction

Standing flank laparotomies are commonly performed in cattle. Intraoperative and postoperative analgesia has been given little attention in production animals, possibly due to financial constraints. With better understanding of nociceptive responses and conscious pain perception in animals, cost-effective analgesic methods should be sought. Currently, local anesthetic techniques are used to provide flank analgesia for standing bovine surgeries (1). Various local techniques have been described to provide acceptable anesthesia to the flank region; however, none of these techniques provide a significant duration of postoperative analgesia. A costeffective method that provides sufficient surgical and postoperative analgesia would be optimal.

Epidural analgesia has become a commonly used method for providing intraoperative and postoperative analgesia in domestic species (2–9). α2-Adrenergic receptor agonists have been used to provide sedation, analgesia, and muscle relaxation in horses and cattle (2–7,10). The analgesic properties of these drugs result from the direct stimulation of α2-adrenergic receptors in the central nervous system (CNS) that inhibits release of norepinepherine and substance P from pain fibers (11). α 2-Adrenergic receptors are concentrated in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord (12), and stimulation of these receptors results in selective sensory blockade without affecting motor function (13).

Romifidine is an imidazolidine derivative, α 2-adrenergic receptor agonist drug labeled for use in horses (11). It has been administered IV, IM, and epidurally in horses, dogs, goats, and cattle, and it has been shown to have systemic and analgesic effects similar to other α 2-agonists (14–17). In cattle, romifidine appears to have similar effects to xylazine, although it may provide a more rapid onset and greater duration of analgesia (14).

Epidural opiods have been used successfully in humans, small animals, horses, and ruminants for controlling pain of various causes (8,9,18–21). These narcotic drugs exert their effects by reducing neurotransmitter release at the presynaptic level and hyperpolarizing postsynaptic neuron membranes by increasing potassium influx into the neuron (22,23). Morphine is among the most common opiods used for analgesia in animals (8,18–20,24). After administration into the epidural space, morphine is believed to be absorbed into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and act on receptors in the substantia gelatinosa of the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, inhibiting the release of substance P (1,24). Epidurally, opiods have the advantage of producing analgesia without motor or sympathetic nerve fiber blockade, making them a good alternative for animals requiring a standing procedure (20). The use of morphineinduced analgesia in cattle is not well documented.

Studies suggest that epidural opiod and α2-adrenergic receptor mediated mechanisms act synergistically to inhibit pain (23,25). Through their synergistic mechanisms, opiods and α 2-adrenergic receptor agonists have been shown to provide more profound and longer lasting analgesia (19,23,25). The purposes of the study reported here were to determine the onset, duration, and degree of analgesia achieved with the epidural administration of a romifidine and morphine combination in cattle.

Materials and methods

Experimental design

Ten healthy adult Holstein Friesen cows weighing between 495 to 710 kg were used in the study. Cows were housed outside in a corral with free access to mixed grass hay and water. Twenty-four hours prior to initiation of the experiment, the cows were moved into indoor stanchion stalls. Each cow had a complete physical examination prior to and at the end of the study, as well as being continually monitored throughout the study. The study protocol was approved by the University of Saskatchewan Animal Care and Use Committee.

Cows were assigned to either a treatment or a control group in a randomized, blinded, crossover design with a minimum 21-day “washout” period between being in treatment and control groups. After surgical preparation of the skin over the 1st intercoccygeal space, the treatment group received a caudal epidural injection consisting of a combination of 50 mg/kg bodyweight (BW) romifidine (Sedivet; Boehringer Ingelheim, Burlington, Ontario) and 0.1 mg/kg BW morphine (Morphine Sulfate; Sabex, Boucherville, Quebec), diluted in 0.9% sterile saline (Physiological saline; Bimeda-MTC Animal Health, Cambridge, Ontario) to a total volume of 30 mL. The control group received a caudal epidural of 30 mL of 0.9% sterile saline. Each epidural was administered by aseptic insertion of an 18-gauge, 4-cm needle into the 1st intercoccygeal epidural space. Correct needle placement in the epidural space was verified by detecting negative pressure with the hanging drop technique (1) and minimal resistance to injection. The individual (EEF) administering each epidural was blinded to the treatments given.

Subjects were assessed for level of flank analgesia and degree of sedation at various time intervals after epidural administration. The individual (EEF) observing individual cow responses was blinded to the treatments given. Flank nociceptive responses were assessed by electrical stimulation of the left paralumbar fossa with a remotely activated electrical stimulator (Beagler 3-dog; Tri-Tronics, Tucson, Arizona, USA). Before the experiment, the hair in the left paralumbar fossa caudal to the last rib was clipped and aseptically prepared. After local anesthesia with 2% lidocaine (Xylocaine; AstraZeneca, Mississauga, Ontario), 2 sutures of #2 polyamide pseudomonofilament (Supramid; Serag Wiessner, 95112 Naila, Germany) were placed through the skin, 10 cm apart. Umbilical tape (3/8 in) was used to attach the electrical stimulator to the sutures to ensure good skin contact. The skin sutures were placed at least 18 h before epidural administration.

Individual responses to 5 increasing levels of electrical stimulation were assessed at 2, 5, 7, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 45, 60, 120, and 180 min and again at 6, 12, and 24 h after epidural administration. Each electrical stimulus was applied remotely, so that the subjects were unaware of the observer. A positive avoidance response (AR) was defined as active movement away from the stimulus or movement of the head, legs, or body in response to the stimulus. Panniculus response and tail twitch alone were not considered a positive AR, as a pilot study had shown that electrical stimulation caused muscle twitches without an apparent conscious nociceptive response, even in cows treated with lidocaine local anesthesia. Each cow received increasing levels of electrical stimulus until a positive AR was observed (Table 1). The level at which a positive AR was first observed was the numerical value given to the cow and defined as the avoidance threshold (AT). A cow was considered to have flank analgesia at a given time period if the AT was significantly higher than the AT observed at time 0.

Table 1.

Voltage, duration, and frequency values for each level of stimulus on the remote electrical stimulator (Beagler 3-dog; Tri-tronics). Each stimulus level consisted of 6 impulses over 15 ms. KV — kilovolts; mamp — milliamperes; Kohm — kilo-ohms; ms —milliseconds

| Stimulus Level | Voltage (KV) | Amplitude (mamp) | Resistance (Kohm) | Duration (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.2 | 30 | 50 | 0.05 |

| 2 | 1.7 | 34 | 50 | 0.06 |

| 3 | 2.4 | 48 | 50 | 0.06 |

| 4 | 3.8 | 76 | 50 | 0.08 |

| 5 | 6.0 | 120 | 50 | 0.08 |

The level of sedation was assessed subjectively on a scale of 1 to 5 (Table 2) at 2, 5, 7, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 45, 60, 120, 180 min and again at 6, 12, and 24 h after epidural administration. Sedation was considered to be acceptable if the cow developed a low head carriage, ptyalism, and a decreased reaction to external stimuli, but showed no signs of recumbency or ataxia (sedation score = 2).

Table 2.

Sedation scoring system for cows receiving either a romifidine (50 μg/kg BW) and morphine (0.1 mg/kg BW) or a 0.9% sterile saline epidural injection. Sedation scores were all subjectively recorded by the same blinded observer (EEF)

| Level of sedation | Subjective assessment criteria |

|---|---|

| 1 | No sedation — cow appears unchanged from initial attitude |

| 2 | Low head carriage, “droopy eyelids,” ptyalism, decreased reaction to external stimuli |

| 3 | Head lowers toward to ground and swaying of the hind legs |

| 4 | Attempts to lie down but aroused with stimulation |

| 5 | Recumbancy and unresponsive to external stimuli |

Heart rates, oxygen saturation (pulse oximetry), and respiratory rates were measured on some randomly selected treated cows within the 2 h of epidural administration.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were performed to verify the data; they showed that the stimulus and sedation scores for the treatment and control groups were not normally distributed. To account for the repeated measures during the study, sedation and stimulus scores for each cow were summed over time and then these sums were evaluated with a Wilcoxon signed-rank test (Statistix for Windows, version 7.0; Analytical Software, Tallahassee, Florida, USA). The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was also performed on sedation and stimulus scores at individual time intervals. Two-tailed P-values were recorded. Statistical significance was determined at P < 0.05.

Results

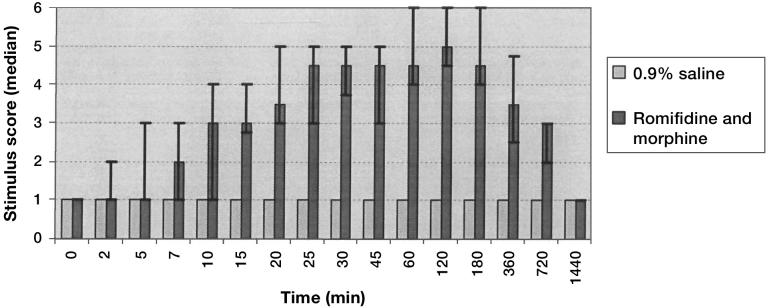

Cows treated with the romifidine and morphine epidural solution showed an increased AT to electrical stimulation compared with control subjects (P = 0.02). The onset of analgesia was 10 min (median stimulus level = 3; P = 0.016; interquartile range stimulus level [IQR] = 1 to 4) after epidural administration, with the highest median stimulus scores occurring between 25 min and 3 h post epidural administration. Twelve hours after epidural administration, cows in the treatment group continued to have statistically significant analgesia of the paralumbar fossa (median stimulus level = 3; P = 0.004; IQR stimulus level = 2 to 3). Control cows showed no evidence of analgesia of the paralumbar fossa or stimulus desensitization throughout the study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Effect of a romifidine (50 μg/kg BW) and morphine (0.1 mg/kg BW) solution or 0.9% saline solution administered epidurally, at a total volume of 30 mL, on stimulus scores in the paralumbar fossa of cattle (n = 10). Error bars represent the 1st and 3rd quartiles at each given time period. Epidurally administered romifidine and morphine had a significant effect compared with saline on median stimulus scores throughout the observation period (P = 0.02).

The epidural administration of the romifidine and morphine solution produced significantly higher sedation scores than the epidural administration of the control solution (P = 0.02). Ten minutes after epidural administration, the treatment group began to show signs of systemic sedation (median sedation level = 2; P = 0.016; IQR sedation level = 1 to 2). Maximal sedative effects occurred between 25 min and 3 h after epidural administration. Treated cows showed pronounced signs of sedation, including swaying of the hind legs, ptyalism, droopy eyelids, and a lowered head carriage. These subjects tended to become recumbent more often than did control subjects, although in both groups, cows lay down at some point during the 24-hour study but would readily stand with encouragement. Six hours after epidural administration, the treatment group remained mildly sedated with drooping lower eyelids, a decreased response to external stimuli, and a lack of appetite (median sedation level = 2; P = 0.002; IQR sedation level = 3 to 5.25). By 24 h after epidural administration, treatment cows were no longer sedated and were eating well. The control group showed no signs of systemic sedation throughout the study (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Median sedation score values for epidural romifidine (50 μg/kg BW) and morphine (0.1 mg/kg BW) or sterile 0.9% saline administered epidurally to a total volume of 30 mL in cattle (n = 10). Error bars represent the 1st and 3rd quartiles at each given time period. Romifidine and morphine had a significant effect compared with saline on median sedation scores throughout the observation period (P = 0.02).

Randomly selected treated cows developed a bradycardia (approximately 30 beats/min) and a decreased respiratory rate by 15 min after epidural administration. Oxygen saturation remained normal (>95%). Treated cows did not show any clinical evidence of rumenal tympany. Twenty-four hours after epidural administration ofromifidine and morphine, 4 of the 10 cows developed a transient watery diarrhea that lasted for approximately 24 h. These diarrheic cows remained bright and alert with a good appetite. One cow developed hind end paresis and became recumbent 24 h after epidural administration of romifidine and morphine. Her condition did not improve despite medical management over a period of 72 h; consequently, she was euthanized. On postmortem examination, there was no necrosis, inflammation, or degenerative changes in the spinal cord on gross or histopathological examination to account for the paresis. The cow had severe muscle necrosis of her adductor muscles, mild hepatic lipidosis, and moderate, acute abomasal ulceration. A 2nd cow showed difficulty in standing and treading of the hind feet 24 h after epidural administration of romifidine and morphine, but this weakness improved over 48 h. This cow also developed digital dermatitis that was treated with oxytetracycline and may have been the cause of the clinical signs.

Discussion

Epidural administration of romifidine and morphine provides significant analgesia of the paralumbar region in cattle. As the cows were only evaluated at 12 and 24 h postepidural administration, the exact duration of analgesia remains speculative. The onset of action of epidural xylazine in cattle is 10 to 30 min and lasts for at least 2 h (2–5). In a study comparing romifidine with xylazine in cattle, the onset of action of romifidine (14.8 min) appeared to be slower than that of xylazine (7.1 min); however, romifidine had a longer duration of action (14). The onset of action of analgesia in this study appears to correlate well with studies on other epidural α 2-adrenergic agonists in cattle (2–4,6,26). In horses, an epidural combination of morphine (0.2 mg/kg BW) and detomidine (0.03 mg/kg BW) has been shown to provide significant clinical analgesia for at least 14 to 16 h (19,24). By combining an α 2-adrenergic agonist and an opiod, the onset and duration of analgesia appears to be maximized. However, it is unknown what role each drug plays in the rapid onset and long duration of these combinations.

The use of a graded electrical stimulator applied to the paralumbar fossa allowed for an objective evaluation of cutaneous analgesia. Subjects could be stimulated from a distance and observed from an unobtrusive location. In this manner, both treatment and control cows were unable to preemptively react to a stimulus or show an AR to the presence of an observer. Through incremental increases in electrical stimulation, a graded response of analgesia could be determined. This graded response provided objective information on the analgesic effects of the drugs studied. Based on clinical observations in a pilot study, the AT for electrical stimulation of level 4 (3.8 KV, 76 mamp, 0.08 ms) corresponded to a standard needle prick test. In a similar study, in which IM and epidural detomidine were used, treated cows tended to respond to needle prick in the flank at voltages greater than 60 mV (0.5 ms duration) (26); however, the current acting on each cow was not specified, making comparisons between the 2 studies difficult.

The level of sedation in cows treated with the romifidine and morphine epidural solution was higher than was determined to be acceptable at the onset of the study. Although treated cows did not appear to become recumbent directly as a result of the epidural, they developed a lowered head carriage and swaying hind limbs for 6 h after epidural administration. As the cows were in stanchion stalls for the duration of the experiment, normal intervals when the cows tended to lie down made it difficult to evaluate whether epidural administration per se had an effect on recumbency. Treated subjects that lay down tended to be more difficult to arouse than control cows and were inappetent for at least 12 h after epidural administration. This level and duration of sedation could be detrimental to patients expected to return to their farms shortly after surgery.

Whether the degree of analgesia produced in the paralumbar fossa was due to local effects in the spinal cord or systemic sedation is difficult to evaluate. It has been shown that the effects of epidural versus IM administration of detomidine in cattle induce comparable degrees of analgesia (26). One theory for the analgesic effects observed was that IM detomidine acted on supraspinal α 2-adrenergic receptors in the brain, while epidural detomidine had its effects locally in the spinal cord (26). However, the total volume of drug administered epidurally may not have been sufficient to achieve cranial migration of drug to the caudal lumbar and sacral spinal cord segments, thus the epidural effects in this study may also be attributable to systemic absorption and central effects in the CNS (26).

It is believed that when administered epidurally, α 2-adrenergic agonists and opiods exert their effects locally in the substantia gelatinosa of the spinal cord (25). Romifidine is highly lipid soluble, promoting a rapid uptake by the vasculature in the epidural space and subsequent systemic absorption. The rapid onset of systemic cardiovascular effects and sedation seen with α 2-adrenergic agonists given epidurally provides evidence for some degree of systemic absorption from the epidural space.

Due to difficulties in interpreting pain behavior in animals, it is difficult to answer the question whether analgesic drugs provide true analgesia or a lack of response solely due to sedation. In the initial period after epidural administration, the onset of analgesia in treated subjects correlated with the onset of sedation. However, as the sedation scores began to decline at 6 h after epidural administration, the analgesic scores remained significant, suggesting that both analgesia and sedation played a role in the subjects’ response to stimulus.

The systemic effects of romifidine have been described in goats, dogs, horses, and cattle (14–17). Similar to other α 2-adrenergic agonists, romifidine has been shown to induce adverse cardiovascular effects, mainly as a result of bradycardia and a reduction in cardiac index (17). In the present study, the systemic effects of romifidine were not evaluated, due to the remote stimulus design of the study to evaluate analgesia and sedation. It was felt that control cows might not reflect normal baseline cardiovascular patterns due to the stress of being approached while being electrically stimulated and thus would associate the observer with the painful stimulus. The treated cows examined were bradycardic and had a decreased respiratory rate, which is in agreement to previous studies (14,17). Further studies on the systemic effects of romifidine in cattle are required before it can be used safely in a clinical setting.

The dosage of romifidine in cattle is not well established. When it was given IM at a dose of 0.02 mg/kg BW to adult cattle, they became recumbent in 15 min and the anesthetic period lasted for approximately 1 h (14). In the current study, a 50 μg/kg BW dose was used, based on a study in goats in which 50 and 75 μg/kg BW romifidine were administered in the subarachnoid space (18). Goats treated with 50 μg/kg BW romifidine had similar levels of analgesia, but with less sedation and cardiovascular depression than did goats treated with 75 μg/kg BW (18). The dose-dependent systemic effects of romifidine have been described in dogs when doses ranging from 5 to 100 μg/kg BW were administered IV (17). Systemic effects of romif idine were minimized by using lower doses; however, these effects were comparable when doses greater than 25 μg/kg BW were administered, suggesting a possible ceiling effect for romifidine (17). In the present study, although the cows did not become recumbent, the degree of sedation documented might have been minimized if a lower dose had been used. Further research is needed to determine a romifidine dose that causes minimal systemic effects while maintaining adequate analgesic effects in cattle.

The use of morphine as an analgesic in cattle is not well documented. Dosing regimens for morphine in most species are between 0.1 and 0.2 mg/kg BW (1). In goats, administration of 0.1 mg/kg BW morphine in the lumbosacral epidural space appeared to provide lower pain scores with minimal sedative or cardiovascular effects when compared with the administration of saline (18). Oxymorphone (0.1 mg/kg BW) administered epidurally to dogs provides analgesia for up to 10 h (9).

The potential synergism between α 2-adrenergic agonists and opiods has been described (23,25). One explanation for the action of opiods on presynaptic neurons is, in part, from the activation of spinal α 2-adrenergic receptors that regulate the responses of these primary afferent neurons to nociceptive stimuli (25). In a study in rats, in which morphine and clonidine were administered in the subarachnoid space, an inhibition of nociceptive activity and activity in ascending axons was seen above what would have been expected from the summation of the effects seen by each drug individually (23). However, the precise mechanism of synergism remains unclear.

The total volume of the administered solution given epidurally in this study was derived from other epidural studies in cattle and the migration of new methylene blue in the epidural space of cattle, horses, goats, and calves (3,28–31). A general volume of 30 mL (~0.05 mL/kg BW) was decided for each cow, in an attempt to standardize the volume for practical use by veterinarians having to estimate doses in the field. By increasing the volume of delivered drug in the epidural space, the cranial extent of migration and analgesia can be increased. In horses, a volume of 0.022 mL/kg BW caused cranial migration of new methylene blue of 6 intervertebral spaces (29). In calves injected epidurally with 0.05 mL/kg BW of new methylene blue, cranial migration of the dye was seen for only 5 intervertebral spaces (30). The variability in cranial migration of new methylene blue in different species is likely due to differences in the size and contents of the spinal canal. In cows given new methylene blue epidurally, the extent of migration of the solution was affected more by individual epidural space variation than by the volume of drug used (28). It was found that epidural fat content was the largest limiting factor in the spread of new methylene blue in the epidural space (28). This suggests that dosing epidural volume by body weight may not provide a consistent degree of analgesia among individuals.

The cranial extent of migration of new methylene blue in the spinal cord reflects the migration of a volume of fluid. Migration of a drug by diffusion or by normal flow of the CSF may be greater than by volume alone. Whether the supraspinal action of drugs administered into the epidural space results from intrathecal rostral spread or uptake into the systemic circulation, and subsequent distribution to the brain, remains to be determined. In humans, it has been found that morphine, administered into the lumbar epidural space, produces segmental analgesia of the spinal cord up to the 2nd cervical dermatome by 2 h, peaking at 5 to 10 h, and persisting for at least 24 h (32). Analgesia at the trigeminal level in the brain was detected 10 h after epidural administration, even though plasma morphine levels were below a detectable limit at this time (32). In dogs, epidural administration of morphine in the lumbosacral epidural space resulted in peak morphine concentrations in the cisternal CSF by 180 min after administration (33). Plasma morphine concentrations peaked at 30 min and were below the measured CSF concentrations by 90 min (33). These results suggest that volume of drug alone does not dictate the cranial extent of action of some drugs and that the effects of epidurally administered morphine are likely due to local migration up the spinal cord in the CSF.

The economic factors associated with analgesic administration in food animals must be taken into consideration. The cost of the romifidine and morphine combination for epidural administration was 3 times the cost of the lidocaine required for a local nerve block (CDN $16 versus CDN $5). Although the romifidine and morphine combination is more expensive, the benefits of sedation and postoperative analgesia may outweigh this difference in price. Comparing the cost of epidural analgesia with the cost of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs labeled for use in cattle, a significant economic benefit is apparent with the use of epidural analgesics.

The cows in the present study did not undergo any surgical procedure. To clinically evaluate the benefits of a α 2-adrenergic agonist and opiod epidural combination, treated cows should undergo a surgical procedure and be assessed for level of surgical and postoperative analgesia. In this study, the onset, duration, and evidence of a graded analgesic response were observed. The level of analgesia achieved in treated cows was likely not sufficient to perform surgery until 20 to 30 min after epidural administration, and the level of analgesia among treated cows at this time varied. These results are similar to those from a study on the effectiveness of epidural xylazine for surgical analgesia during cesarian section in cattle (3). In that study, 70 percent of treated cows achieved sufficient analgesia for surgery; however, the onset of action was 22.6 min (3). This slow time to onset would be detrimental in a clinical setting.

One of the 10 cows in the study developed hind end paresis and recumbency 24 h after epidural administration of romifidine and morphine. The cause of the hind end paresis was not determined and a detailed histopathologic examination of the lumbosaccral spinal cord failed to provide any evidence of injury resulting from the epidural injection. Opiods and α 2-adrenergic agonists do not affect motor nerve fibers and the cow did not become recumbent until after the effects of these drugs had resolved. It is possible that the cow slipped at some point after the 24 h monitoring period and sustained a peripheral nerve obturator injury, resulting in the paresis. The necrosis of the adductor muscles found on postmortem examination may be considered as supporting evidence for this explanation; however, further studies on the use of morphine and romifidine should be undertaken before these drug can be used safely.

Romifidine and morphine are not labeled for use in cattle. Drug withdrawal times have not been published; however, recommendations can be obtained from the Canadian global food animal residue avoidance databank (gFARAD), based at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine in Saskatoon and the Faculté de médicine vétérinaire in St Hyacinthe.

Further research is needed to determine an optimal drug combination and dose that would provide adequate surgical and postoperative analgesia. In the present study, the first known study outlining the analgesic effects in adult cattle, a romifidine and morphine combination administered epidurally provided significant analgesia that lasted for at least 12 h. Further research into withdrawal times, systemic effects, and potential adverse effects are needed before an opiod and α 2-adrenergic agonist combination can be used safely in a clinical setting. CVJ

Footnotes

Reprints will not be available from the author.

References

- 1.Thurmon JC, Tranquilli WJ, Benson GT, eds. Lumb and Jones’ Veterinary Anesthesia. 3rd ed. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1996:169–170,189,193,489–491.

- 2.St Jean G, Skarda RT, Muir WW, Hoffsis GF. Caudal epidural analgesia induced by xylazine administration in cows. Am J Vet Res. 1990;51:1232–1236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caulkett N, Cribb PH, Duke T. Xylazine epidural analgesia for cesarean section in cattle. Can Vet J. 1993;34:674–676. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caulkett NA, MacDonald DG, Janzen ED, Cribb PN, Fretz PB. Xylazine hydrochloride epidural analgesia: A method of providing sedation and analgesia to facilitate castration of mature bulls. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet. 1993;15:1155–1159. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zaugg JL, Nussbaum M. Epidural injection of xylazine: A new option for surgical analgesia of the bovine abdomen and udder. Vet Med. 1990;80:1043–1046. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nowrouzian I, Adib-Hashemi A, Ghamsari SM, Kavoli-Haghighi M. Evaluation of epidural analgesia with xylazine HCL in cattle. Vet Med Rev. 1991;61:13–17. [Google Scholar]

- 7.LeBlanc PH, Caron JP, Patterson JS, Brown M. Epidural injection of xylazine for perineal analgesia in horses. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1988;193:1405–1408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Day TK, Pepper WT, Tobias TA, Flynn MF, Clarke KM. Comparison of intra-articular and epidural morphine for analgesia following stifle arthrotomy in dogs. Vet Surg. 1995;24:522–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950x.1995.tb01366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Popilskis S, Kohn D, Sanchez JA, Gorman P. Epidural vs. intramuscular oxymorphone analgesia after thoracotomy in dogs. Vet Surg. 1991;20:462–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950x.1991.tb00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skarda RT, Muir WW. Analgesic, hemodynamic and respiratory effects induced by caudal epidural administration of meperidine hydrochloride in mares. Am J Vet Res. 2001;62:1001–1006. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2001.62.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adams HR. Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 8th ed. Iowa: Iowa State Univ Pr, 2001:323–324.

- 12.Bouchenafa O, Livingston A. Autoradiographic localization of α -2 adrenoreceptor binding sites in the spinal cord of sheep. Res Vet Sci. 1987;66:382–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yaksh TL. Pharmacology of spinal adrenergic systems which modulate spinal nociceptive processing. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1985;22:845–858. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(85)90537-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Massone F, Luna SP, Castro GB, Meneghello JL, Lopes RS. Sedation with romifidine or xylazine in cattle, is it the same? J Vet Anesth. 1993;20:55. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bouisset S, Saunier D, Le Blaye I, Batut V. L’association tilet- amine/zolazepam romifidine dans l’anesthesie du veau. Rev Med Vet. 2002;153:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amarpal, Kinjavdekar P, Aithal HP, Pawde AM, Pratap K. Analgesic, sedative and hemodynamic effects of spinally administered romifidine in female goats. J Vet Med A. 2002;49:3–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0442.2002.00385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pyppendop BH, Verstegen JP. Cardiovascular effects of romifidine in dogs. Am J Vet Res. 2001;62:490–495. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2001.62.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pablo LS. Epidural morphine in goats after hindlimb orthopedic surgery. Vet Surg. 1993;22:307–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950x.1993.tb00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sysel AM, Pleasant RS, Jacobsen JD, et al. Efficacy of an epidural combination of morphine and detomidine in alleviating experimentally induced hindlimb lameness in horses. Vet Surg. 1996;25:511–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950x.1996.tb01452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leon-Casasola OA, Lema MJ. Postoperative epidural opiod analgesia: What are the choices? Anesth Analg. 1996;83:867–873. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199610000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bromage PR, Camporesi E, Chestnut D. Epidural narcotics for postoperative analgesia. Anesth Analg. 1980;59:473–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dickenson AH. Mechanisms of analgesic actions of opiates and opiods. Br Med Bull. 1991;47:690–702. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilcox GL, Carlsson KH, Jochim A, Jurna I. Mutual potentiation of antinociceptive effects of morphine and clonidine on motor and sensory responses in rat spinal cord. Brain Res. 1987;405:84–93. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90992-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goodrich LR, Nixon AJ, Fubini SL, et al. Epidural morphine and detomidine decreases postoperative hindlimb lameness in horses after bilateral stifle arthroscopy. Vet Surg. 2002;31:232–239. doi: 10.1053/jvet.2002.32436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ossipov MH, Harris S, Lloyd P, Messineo E, Bagley J. Antinociceptive interaction between opiods and medetomidine: Systemic additivity and spinal synergy. Anesthesiology. 1990;73:1227–1235. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199012000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prado ME, Streeter RN, Mandsager RE, Shawley RV, Claypool PL. Pharmacologic effects of epidural versus intramuscular administration of detomidine in cattle. Am J Vet Res. 1999;60:1242–1247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Solomon RE, Gebhart GF. Synergistic antinociceptive interactions among drugs administered to the spinal cord. Anesth Analg. 1994;78:1164–1172. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199406000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee I, Soehartono RH, Yamagishi N. Distribution of new methylene blue injected into the dorsolumbar epidural space in cows. Vet Anesth Analg. 2001;28:140–145. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-2987.2001.00042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hendrickson DA, Southwood LL, Lopez MJ, Kruse-Elliott KT. Cranial migration of different volumes of new-methylene blueafter caudal epidural injection in the horse. Equine Pract. 1998;20:12–14. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lopez MJ, Johnson R, Hendrickson DA, Kruse-Elliott KT. Craniad migration of differing doses of new methylene blue injected into the epidural space after death of calves and juvenile pigs. Am J Vet Res. 1997;58:786–790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson RA, Lopez MJ, Hendrickson DA, Kruse-Elliott KT. Cephalad distribution of three differing volumes of new methylene blue injected into the epidural space in adult goats. Vet Surg. 1996;25:448–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950x.1996.tb01442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Angst MS, Ramaswamy B, Riley ET, Stanski DR. Lumbar epidural morphine in humans and supraspinal analgesia to experimental heat pain. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:312–324. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200002000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valverde A, Conlon PD, Dyson DH, Burger JP. Cisternal CSF and serum concentrations of morphine following epidural administration in the dog. J Vet Pharmacol Ther. 1992;15:91–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2885.1992.tb00991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]