Abstract

Type 1 diabetes is an auto-immune disease resulting in the loss of pancreatic β-cells and, consequently, in chronic hyperglycemia. Insulin supplementation allows diabetic patients to control their glycaemia quite efficiently, but treated patients still display an overall shortened life expectancy and an altered quality of life as compared to their healthy counterparts. In this context and due to the ever increasing number of diabetics, establishing alternative therapies has become a crucial research goal. Most current efforts therefore aim at generating fully functional insulin-secreting β-like cells using multiple approaches. In this review, we screened the literature published since 2011 and inventoried the selected markers used to characterize insulin-secreting cells generated by in vitro differentiation of stem/precursor cells or by means of in vivo transdifferentiation. By listing these features, we noted important discrepancies when comparing the different approaches for the initial characterization of insulin-producing cells as true β-cells. Considering the recent advances achieved in this field of research, the necessity to establish strict guidelines has become a subject of crucial importance, especially should one contemplate the next step, which is the transplantation of in vitro or ex vivo generated insulin-secreting cells in type 1 diabetic patients.

Keywords: β-cells, differentiation, stem cells, type 1 diabetes, β-cell markers

Introduction

Diabetes affects 422 million people worldwide and its increasing prevalence is predicted to reach 552 million patients by 2030 (Whiting et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2016). The most common feature associated with diabetes is also its principal diagnosis: chronic hyperglycemia. Type 2 diabetes results from a combination of insulin resistance in target organs and defective β-cells (Bergman et al., 2002), while type 1 diabetes is due to the autoimmune-mediated loss of the pancreatic insulin-secreting β-cells, leading to insufficient glucose disposal (WHO, 1999). For both pathologies, the loss of insulin activity causes an imbalance in glucose homeostasis, eventually resulting in multiple cardiovascular complications (Hanefeld et al., 1996; Alwan, 2010; Pascolini and Mariotti, 2012). In the case of type 1 diabetes, the hyperglycemia can be efficiently managed by means of insulin supplementation, but patients still display an overall shorter life expectancy and a relatively altered quality of life (Lind et al., 2014; Morgan et al., 2015). In this context, finding an alternative to daily injections of exogenous insulin has become a crucial research goal. Toward this goal, many current efforts focus on β-cell replacement therapies using different strategies, alongside the development of efficient ways to protect such newly generated cells from the autoimmunology inherent to type 1 diabetes (detailed by Desai and Shea, 2016).

During the last decade, impressive progresses have been made toward the generation of functional insulin-secreting β-like cells (Vieira et al., 2016). Most of the strategies employed initially relied on deciphering the molecular mechanisms underlying β-cell (neo) genesis and applying this knowledge to in vitro or in vivo (trans) differentiation: the purpose being to drive progenitor cells (either stem cells or multipotent cells) or differentiated cells toward a β-cell phenotype. To validate the identity of the resulting “β-like” cells, a number of tests have been employed, ranging from marker gene analyses to functional challenges. However, while browsing the recent literature, we noticed important differences between the features examined by various authors. Importantly, our survey indicates that the number of key features assessed to establish whether neo-generated insulin-producing cells are indeed “true” β-cells has not progressed in the last years. These observations clearly establish the need of an “initial β-cell profiling.”

Data analysis

Methodology

Our analyses were focused on the following β-cell features:

- Glucose Stimulated Insulin Secretion (GSIS) was confirmed when the authors reported at least one insulin and/or C-peptide ELISA measurement increasing upon glucose stimulation, or when an improved response for mice subjected to an intraperitoneal or oral glucose tolerance test was observed. Of note, the sole presence of C-Peptide as a sign of GSIS was not considered.

- Gene expression of bone fide β-cell markers was validated when RT-PCR, transcriptomics analyses or immunolabeling was used.

- Mice reverting from an established diabetic state (NOD/Akita background, streptozotocin or alloxan treatment) to stable euglycemia due to the presence of neogenerated insulin-producing cells validated the feature “Hyperglycemia Recovery.” This could be achieved either by in vivo transdifferentiation or allogenic transplantation of in vitro differentiated cells.

Fifty-nine original publications were manually selected following multiple Pubmed searches (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/) using the keywords “β-cells,” “pancreas,” “differentiation,” “stem-cells and markers” in various combinations, limiting the searched period from January 2011 to March 2017 (list in Table 1).

Table 1.

References of the publications analyzed in this survey, listing the source cell types employed for insulin- producing cell neogenesis.

| References | Cell type |

|---|---|

| IN VITRO DIFFERENTIATION OF STEM CELLS | |

| Iskovich et al., 2011 | BM-SC |

| Thatava et al., 2011 | iPSC |

| Talavera-Adame et al., 2011 | mESC |

| Chen et al., 2011 | mESC |

| Criscimanna et al., 2012 | f-LSC |

| Santamaria et al., 2011 | hESC |

| Jeon et al., 2012 | iPSC |

| Lima et al., 2012 | mESC |

| Bose et al., 2012 | hESC |

| Liu and Lee, 2012 | hESC |

| Wei et al., 2013a | hESC |

| Wei et al., 2013b | hESC |

| Tsai et al., 2013 | BM-SC |

| Nair et al., 2014 | mESC |

| Lahmy et al., 2014 | iPSC |

| Ebrahimie et al., 2014 | mESC |

| Niknamasl et al., 2014 | iPSC |

| Shahjalal et al., 2014 | iPSC |

| Hua et al., 2014 | hESC |

| Shaer et al., 2014 | M-SC |

| Van Pham et al., 2014 | hPSC |

| Rezania et al., 2014 | hESC |

| Pagliuca et al., 2014 | hPSC |

| Khorsandi et al., 2015 | BM-SC |

| Jian et al., 2015 | M-SC |

| Pezzolla et al., 2015 | hESC |

| Russ et al., 2015 | hESC |

| Cardinale et al., 2015 | iPSC |

| Agulnick et al., 2015 | hESC |

| Bruin et al., 2015 | hESC |

| Abouzaripour et al., 2016 | f-LSC |

| Salguero-Aranda et al., 2016 | mESC |

| Rajaei et al., 2016 | hESC |

| Manzar et al., in press | iPSC |

| IN VIVO CONVERSION OF MATURE CELLS | |

| Talchai et al., 2012 | Intestinal cells |

| Banga et al., 2012 | Sox9+ cells |

| Al-Hasani et al., 2013 | Pancreatic alpha-cells |

| Courtney et al., 2013 | Pancreatic alpha-cells |

| Chera et al., 2014 | Pancreatic delta-cells |

| Smid et al., 2015 | Pancreatic cells |

| Duan et al., 2015 | Intestinal cells |

| Miyazaki et al., 2016 | Pancreatic acinar cells |

| Yang et al., 2017 | Liver cells |

| Ben-Othman et al., 2017 | Pancreatic alpha-cells |

| Li et al., 2017 | Pancreatic alpha-cells |

| IN VITRO DIFFERENTIATION OF NON-STEM CELLS | |

| Shyu et al., 2011 | Pancreatic cells |

| Zou et al., 2011 | Amniotic fluid cells |

| Ravassard et al., 2011 | Fetal pancreatic buds |

| Kim et al., 2012 | Fibroblasts |

| Akinci et al., 2012 | Pancreatic exocrine cells |

| Lima et al., 2012 | Pancreatic exocrine cells |

| Liu et al., 2013 | Liver cells |

| Kim et al., 2013 | Pancreatic duct cells |

| Wilcox et al., 2013 | Pancreatic α-cells |

| Bouchi et al., 2014 | Gut progenitor cells |

| Sangan et al., 2015 | Pancreatic α-cells |

| Corritore et al., 2014 | Pancreatic duct cells |

| Yamada et al., 2015 | Pancreatic duct cells |

| Teichenne et al., 2015 | Pancreatic acinar cells |

| mESC: mouse embryonic stem cells | BM-SC: bone marrow stem cells |

| iPSC: induced pluripotent stem cells | BT-SC: biliary tree stem cells |

| hESC: human embryonic stem cells | Endo-SC: endometrial stem cells |

| f-LSC: fibroblast-like limbal stem cells | EC-SC: embryonal carcinoma stem cells |

| hPSC: human pluripotent stem cells | M-SC: mesenchymal stem cells |

Validation of β-cell features

Aiming to summarize the β-like cell features assessed, a survey of the recent literature reporting β-like cell neogenesis was conducted by analyzing all the data provided by the authors in order to deliver an accurate compilation. In the resulting 59 original publications, all the properties used to characterize neo-generated β-like cells were inventoried, ranking them by year of publication and the frequency of their use as a validation tool (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of the features assessed in neo-generated β-like cells ranked both chronologically and by frequency.

| Year | Insulin (%) | Pdx1 (%) | GSIS (%) | Nkx6.1/6.2 (%) | Glut2 (%) | NeuroD1 (%) | MafA (%) | Pax4 (%) | HG recovery (%) | Pax6 (%) | Glucokinase (%) | Foxa2 (%) | Isl1 (%) | PC1/3 (%) | Nkx2.2 (%) | Kir6.1/6.2 (%) | Sur1 (%) | PC2 (%) | Hlxb9 (%) | Iapp (%) | Urocortin3 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 100 | 100 | 75 | 50 | 75 | 63 | 38 | 13 | 50 | 63 | 38 | 25 | 25 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 25 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| 2012 | 100 | 90 | 80 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 70 | 80 | 50 | 40 | 40 | 60 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 20 | 20 | 0 |

| 2013 | 100 | 100 | 88 | 50 | 75 | 63 | 75 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 13 | 13 | 38 | 38 | 13 | 13 | 0 | 13 | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| 2014 | 100 | 100 | 92 | 85 | 38 | 38 | 46 | 38 | 31 | 31 | 38 | 15 | 46 | 31 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 15 | 23 |

| 2015 | 100 | 83 | 92 | 42 | 42 | 33 | 50 | 50 | 42 | 17 | 42 | 25 | 17 | 33 | 33 | 25 | 25 | 17 | 0 | 25 | 0 |

| 2016 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 50 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 25 | 75 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2017 | 100 | 75 | 100 | 75 | 25 | 50 | 25 | 50 | 75 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 25 | 0 | 25 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 |

| Total | 100 | 93 | 88 | 59 | 53 | 49 | 49 | 46 | 46 | 36 | 32 | 29 | 29 | 27 | 24 | 22 | 20 | 15 | 12 | 12 | 7 |

For each year, the percentage of publications having validated a particular feature is displayed. GSIS, Glucose Stimulated Insulin Secretion; HG recovery, HyperGlycemia recovery, see Methodology for a description of the validation criteria.

Color gradient reflecting the percentage of validated features.

Insulin and β-cell function

Expectedly, insulin expression was the only feature commonly displayed by all reported neo-generated β-like cells. Interestingly, the responsiveness of such β-like cells to glucose stimulation was assessed in 88% of the publications analyzed, indicating a satisfying physiological response for most of these newly generated cells. However, the recovery upon induced hyperglycemia was validated in only 46% of the publications listed. In the case of insulin-secreting cells generated in vitro and challenged in vivo, this can most likely be attributed to transplantation-related issues and the need to host immune-deficient mice, in vitro differentiated allogeneic or xenogeneic cells being rejected upon graft in wild-type animals. In the case of in vivo transdifferentiation, on the contrary, the immunological rejection is bypassed by the creation of autologous β-like cells, and consequently the hyperglycemic recovery was assessed in all publications except one.

Transcription factors

The Pdx1 gene appeared second in ranking, while being a disputed proof of completed β-cell differentiation (Table 2). Indeed, during the course of pancreas morphogenesis, Pdx1 is first detected in all pancreatic progenitor cells, its expression being subsequently detected in mature β-cells (Ahlgren et al., 1996, 1998). Pdx1 should therefore not be considered as a mature β-cell marker in approaches aiming at recapitulating pancreas development, as one cannot exclude that an undifferentiated proportion of the cells still expresses this transcription factor. We consequently suggest that its presence should solely be assessed in insulin-secreting cells using double labeling.

During pancreas development, an initial expression in pancreatic/endocrine precursors and a subsequent expression in mature β-cells is in fact a feature displayed by numerous transcription factors considered as bona fide β-cell markers. Indeed, HlxB9, Nkx6.1, Pax4, MafA, Nkx2.2, Isl1, NeuroD1, Pax6, Foxa2 are all involved in pancreas organogenesis, their expression being maintained at adult age in β-cells (for the first four) and additional cell subtypes (for the remaining-Ahlgren et al., 1997; Naya et al., 1997; Sander et al., 1997, 2000; Sosa-Pineda et al., 1997; Sussel et al., 1998; Li et al., 1999; Edlund, 2002; Henseleit et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2005). It is thus necessary to validate their expression in insulin-secreting cells either using (q)RT-PCR after FACS sorting or immunohistochemical analyses coupled to insulin detection.

Enzymes and hormones

In the pancreas, glucokinase is expressed in mature α- and β-cells, such enzyme being involved in glucose-sensing (Pierreux et al., 2006). PC1/3 and PC2 correspond to enzymes essential for proinsulin processing and are thus necessary for the normal function of mature β-cells (Marzban et al., 2004; Ugleholdt et al., 2006). Iapp is co-released with insulin by β-cells and acts as a satiation signal (Akesson et al., 2003), while urocortin3 is a hormone secreted by β-cells, acting to induce somatostatin secretion by δ-cells (van der Meulen et al., 2015). Altogether, these proteins are involved in the β-cell metabolism and function, and therefore should mostly be expressed only in mature insulin-secreting cells. Accordingly, they represent markers of the maturation state of differentiated insulin-secreting cells and they should therefore be tested in a more systematic way to ascertain a terminally-differentiated β-like cell phenotype.

Channels

Even though they are not markers of differentiation or maturation per se, potassium channels Kir6.1 and Kir6.2 and ATPbinding cassette channel Sur1 are required for proper insulin secretion (Proks et al., 2002; Kefaloyianni et al., 2013). Coupled to GSIS assessment, the presence of these proteins should be used in order to establish optimal β-like cells response to glucose.

Discussion

Following the outstanding progresses made in the fields of stem-cell differentiation and in vivo trans-differentiation, human applications appear increasingly conceivable. However, one could only contemplate such an exciting clinical outcome after ensuring that the neo-generated insulin-secreting cells are genuine and could therefore fully replace endogenous β-cells. The features displayed in Table 2 rank the common features classically assessed in neo-generated insulin-secreting cells which, taken together, could theoretically constitute an “initial profiling” for β-like cells. Obviously, numerous additional aspects of the β-cell phenotype should be considered when aiming at establishing a standard validation protocol for β-like cells.

Regarding the prerequisites listed in Table 2, as previously discussed, appropriate levels and correct localization of the β-cell-specific marker genes undoubtedly should be confirmed by immunohistochemistry using double labeling, especially in the case of developmental transcription factors. Concerning insulin itself, since its release in response to a stimulus is the main property requested from β-like cells, careful examination of its glucose-stimulated secretion and proper storage of insulin are essential. For the latter, the visualization of secretory vesicles by electronic microscopy appears as a valuable tool. Combined with the PC1/3, PC2, and C-peptide expression analyses, proper processing of proinsulin could be convincingly demonstrated. In addition, the analysis of single insulin-producing cells could provide cues on their ability to behave as endogenous β-cells.

While global proteomic and transcriptomic analysis of neo-generated cells would give detailed information about their state of differentiation, one of the main issues is the heterogeneity of β-cells both in human and rodents (Rutter et al., 2015; Dorrell et al., 2016; Roscioni et al., 2016). A detailed analysis of these aspects, as well as a list of putative routine experiences, are described by James D. Johnson in his elegant review detailing the remaining steps prior to reaching clinical applications (Johnson, 2016). This report provides a thorough analysis of the current state-of-the-art from the point of view of a β-cell biologist, also highlighting the need for standardized protocols validating β-like cells functionality.

In addition to the initial profiling of neo-generated β-like cells, systematic single-cell next generation transcript sequencing (RNA-seq) would be the most decisive validation for β-like cells, providing the complete expression profile of these cells and thus their state of differentiation. Importantly, this transcriptomic phenotyping would not only assess the activation of necessary features, it would ensure the correct repression of non-β-cell genes, including the disallowed genes known to interfere with appropriate β-cell functionality (Pullen and Rutter, 2013; Lemaire et al., 2016; Pullen et al., 2017).

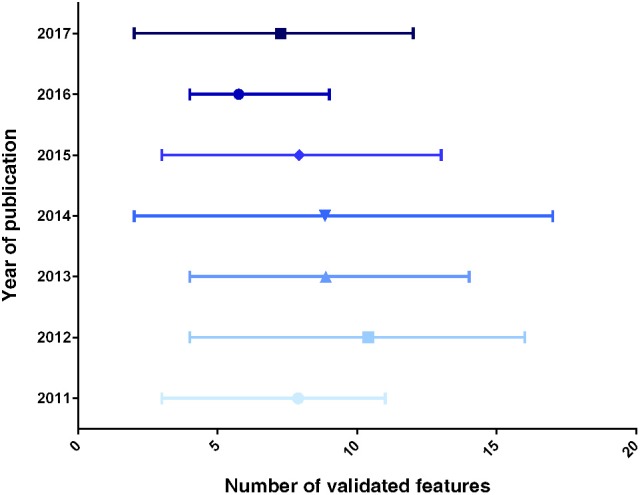

A chronological display of the average number of features assessed in neo-generated β-like cells is provided in Figure 1. Importantly, this ranking clearly shows a scattering in the number of validated features, the average values not increasing in time (which would be indicative of an enhanced scrutiny cells over time). These discrepancies clearly reflect the lack of a canonical list of features to be validated. We thus propose to systematically assess most (if not all) of the features displayed in Table 2 as an initial roadmap toward the establishment of the β-cell identity.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of the number of β-like features validated, per year of publication. The data displayed represent the average number of validated markers ± range, for each year of publication (from the list displayed in Table 2).

Author contributions

AV conceptualized the study, chose the methodology and wrote the original draft. ND, FA, TN, SN, and SS contributed to the formal analysis and investigation. PC validated the results, supervised the study, edited the draft and reviewed the final version prior to submission.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Juvenile Diabetes Research foundation (#3-SRA-2014-282-Q-R, #3-SRA-2017-415-S-B, #3-SRA-2017-416-S-B, #26-2008-639, #17-2013-426), the INSERM AVENIR program, the INSERM, the European Research Council (#StG-2011-281265), the FRM (#DRC20091217179), the ANR/BMBF (#2009 GENO 105 01/01KU0906), the “Investments for the Future” LABEX SIGNALIFE (#ANR-17-ERC2-0004-01, ANR-16-CE18-0005-02), Club Isatis, Mr. and Mrs. Dorato, Mr. and Mrs. Peter de Marffy-Mantuano, the Dujean family, the Fondation Générale de Santé and the Foundation Schlumberger pour l'Education et la Recherche.

References

- Abouzaripour M., Pasbakhsh P., Atlasi N., Shahverdi A. H., Mahmoudi R., Kashani I. R., et al. (2016). In vitro differentiation of insulin secreting cells from mouse bone marrow derived stage-specific embryonic antigen 1 positive stem cells. Cell J. 17, 701–710. 10.22074/cellj.2016.3842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agulnick A., Ambruzs D., Moorman M., Bhoumik A., Cesario R., Payne J., et al. (2015). Insulin-producing endocrine cells differentiated In vitro from human embryonic stem cells function in macroencapsulation devices In vivo. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 4, 1214–1222. 10.5966/sctm.2015-0079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlgren U., Jonsson J., Edlund H. (1996). The morphogenesis of the pancreatic mesenchyme is uncoupled from that of the pancreatic epithelium in IPF1/PDX1-deficient mice. Development 122, 1409–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlgren U., Jonsson J., Jonsson L. (1998). β -cell-specific inactivation of the mouse Ipf1/Pdx1 gene results in loss of the β -cell phenotype and maturity onset? diabetes service of the mouse Ipf1/Pdx1 gene results in loss of the Nl -cell phenotype and maturity onset diabetes. Genes Dev. 12, 1763–1768. 10.1101/gad.12.12.1763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlgren U., Pfaff S. L., Jessell T. M., Edlund T., Edlund H. (1997). Independent requirement for ISL1 in formation of pancreatic mesenchyme and islet cells. Nature 385, 257–260. 10.1038/385257a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akesson B., Panagiotidis G., Westermark P., Lundquist I. (2003). Islet amyloid polypeptide inhibits glucagon release and exerts a dual action on insulin release from isolated islets. Regul. Pept. 111, 55–60. 10.1016/S0167-0115(02)00252-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akinci E., Banga A., Greder L. V., Dutton J. R., Slack J. M. W. (2012). Reprogramming of pancreatic exocrine cells toward a beta (β) cell character using Pdx1, Ngn3 and MafA. Biochem. J. 442, 539–550. 10.1042/BJ20111678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hasani K., Pfeifer A., Courtney M., Ben-Othman N., Gjernes E., Vieira A., et al. (2013). Adult duct-lining cells can reprogram into β-like cells able to counter repeated cycles of toxin-induced diabetes. Dev. Cell 26, 86–100. 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alwan A. (2010). Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases. Geneva: World Health. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Othman N., Vieira A., Courtney M., Record F., Gjernes E., Avolio F., et al. (2017). Long-term GABA administration induces alpha cell-mediated beta-like cell neogenesis. Cell 168, 73.e11–85.e11. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman R. N., Ader M., Huecking K., Van Citters G. (2002). Accurate assessment of β-cell function: the hyperbolic correction. Diabetes 51(Suppl. 1), S212–S220. 10.2337/diabetes.51.2007.S212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banga A., Akinci E., Greder L. V., Dutton J. R., Slack J. M. W. (2012). In vivo reprogramming of Sox9+ cells in the liver to insulin-secreting ducts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 15336–15341. 10.1073/pnas.1201701109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose B., Shenoy P. S., Konda S., Wangikar P. (2012). Human embryonic stem cell differentiation into insulin secreting β-cells for diabetes. Cell Biol. Int. 36, 1013–1020. 10.1042/CBI20120210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchi R., Foo K. S., Hua H., Tsuchiya K., Ohmura Y., Sandoval P. R., et al. (2014). FOXO1 inhibition yields functional insulin-producing cells in human gut organoid cultures. Nat. Commun. 5:4242. 10.1038/ncomms5242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruin J. E., Asadi A., Fox J. K., Erener S., Rezania A., Kieffer T. J. (2015). Accelerated maturation of human stem cell-derived pancreatic progenitor cells into insulin-secreting cells in immunodeficient rats relative to mice. Stem Cell Rep. 5, 1081–1096. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.10.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardinale V., Puca R., Carpino G., Scafetta G., Renzi A., De Canio M., et al. (2015). Adult human biliary tree stem cells differentiate to? β-pancreatic islet cells by treatment with a recombinant human Pdx1 peptide. PLoS ONE 10:e0134677. 10.1371/journal.pone.0134677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Chai J., Singh L., Kuo C.-Y., Jin L., Feng T., et al. (2011). Characterization of an in vitro differentiation assay for pancreatic-like cell development from murine embryonic stem cells: detailed gene expression analysis. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 9, 403–419. 10.1089/adt.2010.0314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chera S., Baronnier D., Ghila L., Cigliola V., Jensen J. N., Gu G., et al. (2014). Diabetes recovery by age-dependent conversion of pancreatic δ-cells into insulin producers. Nature 514, 503–507. 10.1038/nature13633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corritore E., Dugnani E., Pasquale V., Misawa R., Witkowski P., Lei J., et al. (2014). β-cell differentiation of human pancreatic duct-derived cells after in vitro expansion. Cell. Reprogram. 16, 456–466. 10.1089/cell.2014.0025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney M., Gjernes E., Druelle N., Ravaud C., Vieira A., Ben-Othman N., et al. (2013). The inactivation of Arx in pancreatic alpha-cells triggers their neogenesis and conversion into functional β-like cells. PLoS Genet. 9:e1003934. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criscimanna A., Zito G., Taddeo A., Richiusa P., Pitrone M., Morreale D., et al. (2012). In vitro generation of pancreatic endocrine cells from human adult fibroblast-like limbal stem cells. Cell Transplant. 21, 73–90. 10.3727/096368911X580635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai T., Shea L. D. (2016). Advances in islet encapsulation technologies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 16, 338–350. 10.1038/nrd.2016.232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorrell C., Schug J., Canaday P. S., Russ H. A., Tarlow B. D., Grompe M. T., et al. (2016). Human islets contain four distinct subtypes of β cells. Nat. Commun. 7:11756. 10.1038/ncomms11756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan F. F., Liu J. H., March J. C. (2015). Engineered commensal bacteria reprogram intestinal cells into glucose-responsive insulin-secreting cells for the treatment of diabetes. Diabetes 64, 1794–1803. 10.2337/db14-0635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimie M., Esmaeili F., Cheraghi S., Houshmand F., Shabani L., Ebrahimie E. (2014). Efficient and simple production of insulin-producing cells from embryonal carcinoma stem cells using mouse neonate pancreas extract, as a natural inducer. PLoS ONE 9:e90885. 10.1371/journal.pone.0090885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlund H. (2002). Pancreatic organogenesis–developmental mechanisms and implications for therapy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3, 524–532. 10.1038/nrg841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanefeld M., Fischer S., Julius U., Schulze J., Schwanebeck U., Schmechel H., et al. (1996). Risk factors for myocardial infarction and death in newly detected NIDDM: the diabetes intervention study, 11-year follow-up. Diabetologia 39, 1577–1583. 10.1007/s001250050617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henseleit K. D., Nelson S. B., Kuhlbrodt K., Hennings J. C., Ericson J., Sander M. (2005). NKX6 transcription factor activity is required for alpha- and beta-cell development in the pancreas. Development 132, 3139–3149. 10.1242/dev.01875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua X., Wang Y., Tang Y., Yu S., Jin S., Meng X., et al. (2014). Pancreatic insulin-producing cells differentiated from human embryonic stem cells correct hyperglycemia in SCID/NOD mice, an animal model of diabetes. PLoS ONE 9:e102198. 10.1371/journal.pone.0102198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iskovich S., Goldenberg-cohen N., Stein J., Yaniv I., Farkas D. L., Askenasy N. (2011). β-cell neogenesis?: experimental considerations in adult stem cell differentiation. 20, 569–582. 10.1089/scd.2010.0342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon K., Lim H., Kim J.-H., Thuan N. V., Park S. H., Lim Y.-M., et al. (2012). Differentiation and transplantation of functional pancreatic beta cells generated from induced pluripotent stem cells derived from a type 1 diabetes mouse model. Stem Cells Dev. 21, 2642–2655. 10.1089/scd.2011.0665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jian R. L., Mao L. B., Xu Y., Li X. F., Wang F. P., Luo X. G., et al. (2015). Generation of insulin-producing cells from C3H10T1/2 mesenchymal progenitor cells. Gene 562, 107–116. 10.1016/j.gene.2015.02.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J. D. (2016). The quest to make fully functional human pancreatic beta cells from embryonic stem cells: climbing a mountain in the clouds. Diabetologia 59, 1–11. 10.1007/s00125-016-4059-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kefaloyianni E., Lyssand J. S., Moreno C., Delaroche D., Hong M., Fenyö D., et al. (2013). Comparative proteomic analysis of the ATP-sensitive K+ channel complex in different tissue types. Proteomics 13, 368–378. 10.1002/pmic.201200324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khorsandi L., Nejad-Dehbashi F., Ahangarpour A., Hashemitabar M. (2015). Three-dimensional differentiation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells into insulin-producing cells. Tissue Cell 47, 66–72. 10.1016/j.tice.2014.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B., Yoon B. S., Moon J., Kim J., Jun E. K., Lee J. H., et al. (2012). Differentiation of human labia minora dermis-derived fibroblasts into insulin-producing cells. Exp. Mol. Med. 44, 26–35. 10.3858/emm.2012.44.1.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. S., Hong S. H., Oh S. H., Kim J. H., Lee M. S., Lee M. K. (2013). Activin a, exendin-4, and glucose stimulate differentiation of human pancreatic ductal cells. J. Endocrinol. 217, 241–252. 10.1530/JOE-12-0474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahmy R., Soleimani M., Sanati M. H., Behmanesh M., Kouhkan F., Mobarra N. (2014). MiRNA-375 promotes beta pancreatic differentiation in human induced pluripotent stem (hiPS) cells. Mol. Biol. Rep. 41, 2055–2066. 10.1007/s11033-014-3054-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire K., Thorrez L., Schuit F. (2016). Disallowed and allowed gene expression: two faces of mature islet Beta cells. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 36, 45–71. 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071715-050808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Arber S., Jessell T. M., Edlund H. (1999). Selective agenesis of the dorsal pancreas in mice lacking homeobox gene Hlxb9. Nat. Genet. 23, 67–70. 10.1038/12669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Casteels T., Frogne T., Ingvorsen C., Honoré C., Courtney M., et al. (2017). Artemisinins target GABAA receptor signaling and impair α cell identity. Cell 168, 86.e15–100.e15. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima M. J., Docherty H. M., Chen Y., Vallier L., Docherty K. (2012). Pancreatic transcription factors containing protein transduction domains drive mouse embryonic stem cells toward endocrine pancreas. PLoS ONE 7:e36481. 10.1371/journal.pone.0036481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind M., Svensson A.-M., Kosiborod M., Gudbjörnsdottir S., Pivodic A., Wedel H., et al. (2014). Glycemic control and excess mortality in type 1 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 1972–1982. 10.1056/NEJMoa1408214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Liu Y., Wang H., Hao H., Han Q., Shen J., et al. (2013). Direct differentiation of hepatic stem-like WB cells into insulin-producing cells using small molecules. Sci. Rep. 3:1185. 10.1038/srep01185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S.-H., Lee L.-T. (2012). Efficient differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells into insulin-producing cells. Exp. Diab. Res. 2012, 1–5. 10.1155/2012/201295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzar G. S., Kim E.-M., Zavazava N. (in press). Demethylation of induced pluripotent stem cells from type 1 diabetic patients enhances differentiation into functional pancreatic β-cells. J. Biol. Chem. 10.1074/jbc.m117.784280. Available online at: http://www.jbc.org/content/early/recent [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Marzban L., Trigo-Gonzalez G., Zhu X., Rhodes C. J., Halban P. A., Steiner D. F., et al. (2004). Role of beta-cell prohormone convertase (PC)1/3 in processing of pro-islet amyloid polypeptide. Diabetes 53, 141–148. 10.2337/diabetes.53.1.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki S., Tashiro F., Miyazaki J., Montanya E., Nacher V., Biarnés M., et al. (2016). Transgenic expression of a single transcription factor Pdx1 induces transdifferentiation of pancreatic acinar cells to endocrine cells in adult mice. PLoS ONE 11:e0161190. 10.1371/journal.pone.0161190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan E., Cardwell C. R., Black C. J., McCance D. R., Patterson C. C. (2015). Excess mortality in Type 1 diabetes diagnosed in childhood and adolescence: a systematic review of population-based cohorts. Acta Diabetol. 52, 801–807. 10.1007/s00592-014-0702-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair G. G., Vincent R. K., Odorico J. S. (2014). Ectopic Ptf1a expression in murine ESCs potentiates endocrine differentiation and models pancreas development in vitro. Stem Cells 32, 1195–1207. 10.1002/stem.1616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naya F. J., Huang H. P., Qiu Y., Mutoh H., DeMayo F. J., Leiter A. B., et al. (1997). Diabetes, defective pancreatic morphogenesis, and abnormal enteroendocrine differentiation in BETA2/NeuroD-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 11, 2323–2334. 10.1101/gad.11.18.2323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niknamasl A., Ostad S. N., Soleimani M., Azami M., Salmani M. K., Lotfibakhshaiesh N., et al. (2014). A new approach for pancreatic tissue engineering: human endometrial stem cells encapsulated in fibrin gel can differentiate to pancreatic islet beta-cell. Cell Biol. Int. 38, 1174–1182. 10.1002/cbin.10314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagliuca F. W., Millman J. R., Gurtler M., Segel M., Van Dervort A., Ryu J. H., et al. (2014). Generation of functional human pancreatic β cells in vitro. Cell 159, 428–439. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascolini D., Mariotti S. P. (2012). Global estimates of visual impairment: 2010. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 96, 614–618. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezzolla D., Lopez-Beas J., Lachaud C. C., Dominguez-Rodriguez A., Smani T., Hmadcha A., et al. (2015). Resveratrol ameliorates the maturation process of β-cell-like cells obtained from an optimized differentiation protocol of human embryonic stem cells. PLoS ONE 10:e0119904. 10.1371/journal.pone.0119904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierreux C. E., Poll A. V., Kemp C. R., Clotman F., Maestro M. A., Cordi S., et al. (2006). The transcription factor hepatocyte nuclear factor-6 controls the development of pancreatic ducts in the mouse. Gastroenterology 130, 532–541. 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proks P., Reimann F., Green N., Gribble F., Ashcroft F. (2002). Sulfonylurea stimulation of insulin secretion. Diabetes 51(Suppl. 3), S368–S376. 10.2337/diabetes.51.2007.s368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullen T. J., Huising M. O., Rutter G. A. (2017). Analysis of purified pancreatic islet beta and alpha cell transcriptomes reveals 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (Hsd11b1) as a novel disallowed gene. Front. Genet. 8:41. 10.3389/fgene.2017.00041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullen T. J., Rutter G. A. (2013). When less is more: the forbidden fruits of gene repression in the adult β-cell. Diab. Obes. Metab. 15, 503–512. 10.1111/dom.12029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajaei B., Shamsara M., Fakhr Taha M., Amirabad L. M., Massumi M., Sanati M. H. (2016). Pancreatic endoderm-derived from diabetic patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cell generates glucose-responsive insulin-secreting cells. J. Cell. Physiol. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1002/jcp.25459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravassard P., Hazhouz Y., Pechberty S., Bricout-neveu E., Armanet M., Czernichow P., et al. (2011). Technical advance A genetically engineered human pancreatic β cell line exhibiting glucose-inducible insulin secretion. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 3589–3597. 10.1172/JCI58447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezania A., Bruin J. E., Arora P., Rubin A., Batushansky I., Asadi A., et al. (2014). Reversal of diabetes with insulin-producing cells derived in vitro from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 1121–1133. 10.1038/nbt.3033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscioni S. S., Migliorini A., Gegg M., Lickert H. (2016). Impact of islet architecture on β-cell heterogeneity, plasticity and function. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 12, 695–709. 10.1038/nrendo.2016.147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russ H. A., Parent A. V., Ringler J. J., Hennings T. G., Nair G. G., Shveygert M., et al. (2015). Controlled induction of human pancreatic progenitors produces functional beta-like cells in vitro. EMBO J. 34:e201591058. 10.15252/embj.201591058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter G. A., Pullen T. J., Hodson D. J., Martinez-Sanchez A. (2015). Pancreatic β-cell identity, glucose sensing and the control of insulin secretion. Biochem. J. 466, 203–218. 10.1042/BJ20141384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salguero-Aranda C., Tapia-Limonchi R., Cahuana G. M., Hitos A. B., Diaz I., Hmadcha A., et al. (2016). Differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells toward functional pancreatic β-cell surrogates through epigenetic regulation of Pdx1 by nitric oxide. Cell Transplant. 25, 1879–1892. 10.3727/096368916X691178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander M., Neubüser A., Kalamaras J., Ee H. C., Martin G. R., German M. S. (1997). Genetic analysis reveals that PAX6 is required for normal transcription of pancreatic hormone genes and islet development. Genes Dev. 11, 1662–1673. 10.1101/gad.11.13.1662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander M., Sussel L., Conners J., Scheel D., Kalamaras J., Dela Cruz F., et al. (2000). Homeobox gene Nkx6.1 lies downstream of Nkx2.2 in the major pathway of β-cell formation in the pancreas. Development 127, 5533–5540. 10.1101/gad.11.13.1662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangan C. B., Jover R., Heimberg H., Tosh D. (2015). In vitro reprogramming of pancreatic alpha cells toward a beta cell phenotype following ectopic HNF4α expression. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 399, 50–59. 10.1016/j.mce.2014.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santamaria X., Massasa E. E., Feng Y., Wolff E., Taylor H. S. (2011). Derivation of insulin producing cells from human endometrial stromal stem cells and use in the treatment of murine diabetes. Mol. Ther. 19, 2065–2071. 10.1038/mt.2011.173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaer A., Azarpira N., Vahdati A., Karimi M. H., Shariati M. (2014). miR-375 induces human decidua basalis-derived stromal cells to become insulin-producing cells. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 19, 483–499. 10.2478/s11658-014-0207-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahjalal H., Shiraki N., Sakano D., Kikawa K., Ogaki S., Baba H., et al. (2014). Generation of insulin-producing β -like cells from human iPS cells in a defined and completely xeno-free culture system. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 394–408. 10.1093/jmcb/mju029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyu J. F., Wang H. S., Shyr Y. M., Wang S. E., Chen C. H., Tan J. S., et al. (2011). Alleviation of hyperglycemia in diabetic rats by intraportal injection of insulin-producing cells generated from surgically resected human pancreatic tissue. J. Endocrinol. 208, 233–244. 10.1677/JOE-10-0352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smid J. K., Faulkes S., Rudnicki M. A. (2015). Periostin induces pancreatic regeneration. Endocrinology 156, 824–836. 10.1210/en.2014-1637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosa-Pineda B., Chowdhury K., Torres M., Oliver G., Gruss P. (1997). The Pax4 gene is essential for differentiation of insulin prod β cells in the mammalian pancreas.pdf. Nature 386, 399–402. 10.1038/386399a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussel L., Kalamaras J., Hartigan-O'Connor D. J., Meneses J. J., Pedersen R. A., Rubenstein J. L., et al. (1998). Mice lacking the homeodomain transcription factor Nkx2.2 have diabetes due to arrested differentiation of pancreatic beta cells. Development 125, 2213–2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talavera-Adame D., Wu G., He Y., Ng T. T., Gupta A., Kurtovic S., et al. (2011). Endothelial cells in co-culture enhance embryonic stem cell differentiation to pancreatic progenitors and insulin-producing cells through BMP signaling. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 7, 532–543. 10.1007/s12015-011-9232-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talchai C., Xuan S., Kitamura T., Depinho R. A., Accili D. (2012). Generation of functional insulin-producing cells in the gut by Foxo1 ablation. Nat. Genet. 44, 406–412. 10.1038/ng.2215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teichenne J., Morró M., Casellas A., Jimenez V., Tellez N., Leger A., et al. (2015). Identification of miRNAs involved in reprogramming acinar cells into insulin producing cells. PLoS ONE 10:e0145116. 10.1371/journal.pone.0145116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thatava T., Nelson T. J., Edukulla R., Sakuma T., Ohmine S., Tonne J. M., et al. (2011). Indolactam V/GLP-1-mediated differentiation of human iPS cells into glucose-responsive insulin-secreting progeny tayaramma. Gene Ther. 18, 283–293. 10.1038/gt.2010.145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai P. J., Wang H. S., Lin C. H., Weng Z. C., Chen T. H., Shyu J. F. (2013). Intraportal injection of insulin-producing cells generated from human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells decreases blood glucose level in diabetic rats. Endocr. Res. 39, 26–33. 10.3109/07435800.2013.797432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugleholdt R., Poulsen M.-L. H., Holst P. J., Irminger J.-C., Orskov C., Pedersen J., et al. (2006). Prohormone convertase 1/3 is essential for processing of the glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide precursor. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 11050–11057. 10.1074/jbc.M601203200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Meulen T., Donaldson C. J., Cáceres E., Hunter A. E., Cowing-Zitron C., Pound L. D., et al. (2015). Urocortin3 mediates somatostatin-dependent negative feedback control of insulin secretion. Nat. Med. 21, 769–776. 10.1038/nm.3872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Pham P., Thi-My Nguyen P., Thai-Quynh Nguyen A., Minh Pham V., Nguyen-Tu Bui A., Thi-Tung Dang L., et al. (2014). Improved differentiation of umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells into insulin-producing cells by PDX-1 mRNA transfection. Differentiation 87, 200–208. 10.1016/j.diff.2014.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira A., Courtney M., Druelle N., Avolio F., Napolitano T., Hadzic B., et al. (2016). β-cell replacement as a treatment for type 1 diabetes: an overview of possible cell sources and current axes of research. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 18, 137–143. 10.1111/dom.12721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei R., Yang J., Hou W., Liu G., Gao M., Zhang L., et al. (2013a). Insulin-producing cells derived from human embryonic stem cells: comparison of definitive endoderm- and nestin-positive progenitor-based differentiation strategies. PLoS ONE 8:e72513. 10.1371/journal.pone.0072513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei R., Yang J., Liu G.-Q., Gao M., Hou W.-F., Zhang L., et al. (2013b). Dynamic expression of microRNAs during the differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into insulin-producing cells. Gene 518, 246–255. 10.1016/j.gene.2013.01.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiting D. R., Guariguata L., Weil C., Shaw J. (2011). IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2011 and 2030. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 94, 311–321. 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (1999). Definition, Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus and its Complications. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox C. L., Terry N. A., Walp E. R., Lee R. A., May C. L. (2013). Pancreatic alpha-cell specific deletion of mouse arx leads to α-cell identity loss. PLoS ONE 8:e66214. 10.1371/journal.pone.0066214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T., Cavelti-Weder C., Caballero F., Lysy P. A., Guo L., Sharma A., et al. (2015). Reprogramming mouse cells with a pancreatic duct phenotype to insulin-producing β-like cells. Endocrinology 156, 2029–2038. 10.1210/en.2014-1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X.-F., Ren L.-W., Yang L., Deng C.-Y., Li F.-R. (2017). In vivo direct reprogramming of liver cells to insulin producing cells by virus-free overexpression of defined factors. Endocr. J. 64, 291–302. 10.1507/endocrj.EJ16-0463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L., Guo M., Matsuoka T. A., Hagman D. K., Parazzoli S. D., Poitout V., et al. (2005). The islet β cell-enriched MafA activator is a key regulator of insulin gene transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 11887–11894. 10.1074/jbc.M409475200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B., Lu Y., Hajifathalian K., Bentham J., Di Cesare M., Danaei G., et al. (2016). Worldwide trends in diabetes since 1980: a pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4.4 million participants. Lancet 387, 1513–1530. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00618-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou G., Liu T., Zhang L., Liu Y., Li M., Du X., et al. (2011). Induction of pancreatic β-cell-like cells from CD44+/CD105+ human amniotic fluids via epigenetic regulation of the pancreatic and duodenal homeobox factor 1 promoter. DNA Cell Biol. 30, 739–748. 10.1089/dna.2010.1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]