Abstract

Background

Early lifetime exposure to dietary or supplementary vitamin D has been predicted to be a risk factor for later allergy. Twin studies suggest that response to vitamin D exposure might be influenced by genetic factors. As these effects are primarily mediated through the vitamin D receptor (VDR), single base variants in this gene may be risk factors for asthma or allergy.

Results

951 individuals from 224 pedigrees with at least 2 asthmatic children were analyzed for 13 SNPs in the VDR. There was no preferential transmission to children with asthma. In their unaffected sibs, however, one allele in the 5' region was 0.5-fold undertransmitted (p = 0.049), while two other alleles in the 3' terminal region were 2-fold over-transmitted (p = 0.013 and 0.018). An association was also seen with bronchial hyperreactivity against methacholine and with specific immunoglobulin E serum levels.

Conclusion

The transmission disequilibrium in unaffected sibs of otherwise multiple-affected families seem to be a powerful statistical test. A preferential transmission of vitamin D receptor variants to children with asthma could not be confirmed but raises the possibility of a protective effect for unaffected children.

Background

Early exposure to dietary and supplementary vitamin D has been predicted to be a risk factor for later allergy and asthma [1]. Supported by in vitro [2] and in vivo studies [3], also epidemiological studies [4,5] report a positive association between supplementary vitamin D use and later allergy [6].

Vitamin D has been used for many years in various doses and preparations to prevent rickets, a disease usually induced by poor dietary calcium intake and sun deprivation. It seems that widespread "historical" rickets in industrial countries was also a genetic disease. A formal twin analysis yielded a 91% concordance rate in monozygotic twins compared to 23% in dizygotic twins [7]. Also a very recent study of baseline gene expression in lymphoblastoid cell-lines found the expression of at least four vitamin D related genes as a heritable trait [pers. comm. Monks 2004], which also makes a genetically determined vitamin D sensitivity likely. It may be speculated that common rickets is the low sensitivity form (in the absence of proper endogenous vitamin D production), and allergy the high sensitivity form (in the presence of high oral vitamin D exposure).

The active vitamin D metabolite 1,25(OH)2D3 binds to nuclear vitamin D receptor (VDR), which exists from under 500 to over 25,000 copies / cell in many human tissues including thymus, bone marrow, B and T cells and lung alveolar cells [8]. The gene for VDR was cloned in 1988, it consists of 9 exons with at least 6 isoforms of exon 1 and spans 60–70 kb of genomic sequence (Fig. 1) [8]. The VDR is also a first-order positional candidate as nearly all asthma and allergy linkage studies found linkage on chromosome 12q [9,10]. While an own study of a single Fok1 restriction site (that alters the ATG start codon in the second exon of the VDR) in asthma families did not find an association [11], positive association of several VDR variants with asthma has been shown in the meantime by two U.S. [12] as well as one Canadian study [13].

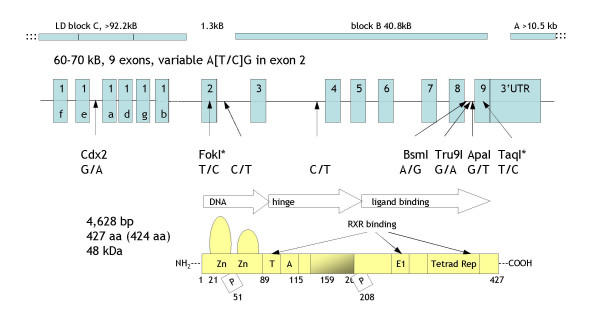

Figure 1.

Structure of the vitamin D receptor [40, 41]. Upper: LD blocks in Caucasians [14] where blocks "C" and "A" extend to both sides. In Africans block "C" is split into 3 parts, "C1", "C2" and "C3". Middle: Exon structure including several SNP variants examined in about 100 disease-association studies. Lower: Aligned protein domains, DNA binding, hinge and ligand binding region including phosphorylation sites.

So far, dbSNP catalogued 117 SNPs in the VDR when a resequencing approach of the VDR published in June 2004 found 245 SNPs [14]. In this study three LD blocks were localized. Block "A" at the 3' end of exon 9 spans approximately 10.5 kb. VDR exons 3 – 9 are situated in block "B", which spans 40.8 kb. A 5.7 kb LD-breaking spot separates blocks "A" and "B", while blocks "B" and "C" are separated by a 1.3 kb LD-breaking spot; this region also includes VDR exon 2 and the commonly studied FokI SNP. All three LD blocks have now been covered by additional SNPs in our asthma family sample.

Results

The sample analyzed here consisted of 951 individuals from 224 pedigrees contributing 11,383 genotypes.

Mean pedigree size was 4.4; the number of phase-known individuals ranged from 221 to 305 (with the exception of rs2853563) in affected, and from 24 to 41 in the unaffected, children. Except for rs2853563, the minor allele frequency always exceeded 19%. In two families both parents had asthma, in 82 only one parent had asthma and in 140 families both parents were disease-free.

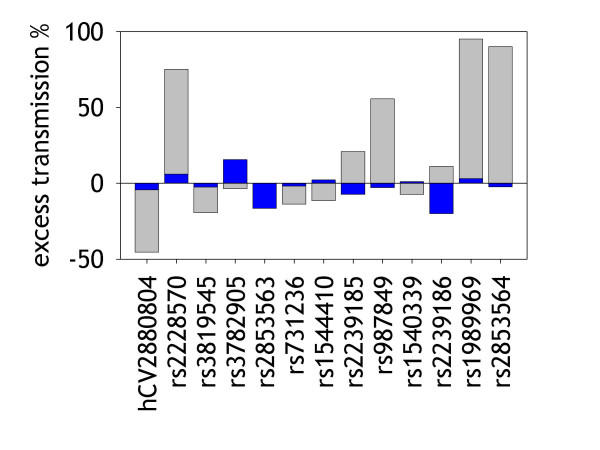

Of the markers tested, only marker rs2239186 showed a slightly reduced transmission ratio in asthmatic children (0.8, P = 0.073). In unaffected children three markers showed significantly altered ratios: 0.5 for hCV2880804, and 2.0 and 1.9 in rs1989969 and rs2853564, respectively. Excess transmission was generally more pronounced in unaffected children (Fig. 2), however, the three significant associations would also not persist if adjusted for multiple testing with the method described by Bonferroni.

Figure 2.

Excess transmission of VDR-SNPs in asthma families. Blue bars indicate transmission to affected children, grey bars transmission to unaffected children.

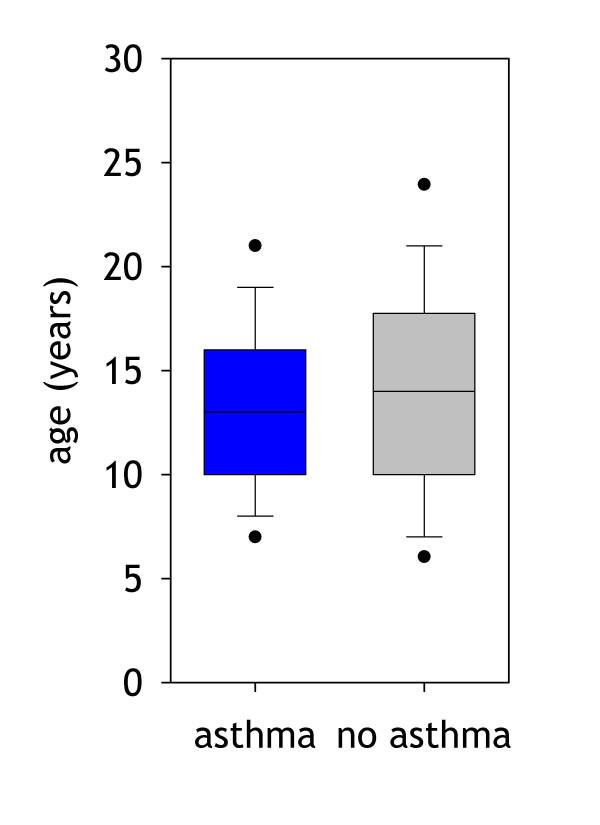

The TDTDS test as a global family test seems to capture the information both from affected and unaffected children, with four SNPs being at least marginally significantly associated at the 5% level. As unaffected children might be the younger children (that still have not developed a phenotype), the age distribution of affected and unaffected children was also compared (Fig. 3) but no difference was found. Affected and non affected children, however, show several other differences, all known as risk factors and symptoms for asthma: There are more boys in the affected group (57,6% vs. 36,1%), they are more often exposed to indoor environmental tobacco smoke (43.0% vs. 31.7%) and they are suffering more frequently from eczema (43,0% vs. 26,9%). Their average log(IgE) values are higher (7,7 kU/l vs. 5,8 kU/l), their forced 1 second capacity FEV1 is lower (2387 ml vs. 2625 ml) together with the forced vital capacity (2876 vs. 2998).

Figure 3.

Age distribution in children with, blue box (left), and without asthma, grey box (right).

Bronchial hyper-reactivity (BHR), measured as quantitative trait locus (QTL) by using the slope of the dose-response curve in a standardized methacholine challenge protocol, also indicated an association with the same three SNPs identified in unaffected sibs. Further dichotomizing BHR by comparing the upper versus all other quartiles also yielded significant associations (hCV2880804, P = 0.005, rs1989969 P = 0.001, rs2853564 P = 0.001). The sum score of all specific IgE serum levels (RAST) was associated with markers rs1989969 (P = 0.021) and rs2853564 (P = 0.018), while total IgE was not found to be associated.

Table 2 summarizes the LD structure of all SNPs in the German families. LD was generally low, except for three SNPs on block "B". SNP rs2853563 probably does not interrupt block "B", as might be concluded from table 2, as this marker has a very low minor allele frequency (table 1). The overall low LD was very similar in the Swedish and Turkish subgroups of our families and are in line with recently published data [12-14]. The association seen for the two SNPs at the 3'-terminal region is probably influenced by the high LD between these two SNPs.

Table 2.

D' matrix of 13 VDR-SNPs in German parents. D' values > = 0.69 are indicated in bold.

| rs2228570 | rs3819545 | rs3782905 | rs2853563 | rs731236 | rs1544410 | rs2239185 | rs987849 | rs1540339 | rs2239186 | rs1989969 | rs2853564 | |

| hCV2880804 | 0,01 | 0,02 | -0,04 | 0,05 | 0,01 | 0,01 | -0,02 | -0,01 | 0,05 | 0,02 | -0,27 | -0,27 |

| Rs2228570 | 0,02 | -0,03 | 0,01 | 0,06 | 0,02 | -0,01 | -0,03 | -0,03 | -0,10 | 0,12 | 0,13 | |

| Rs3819545 | -0,53 | 0,08 | -0,41 | -0,41 | 0,26 | 0,25 | 0,85 | 0,58 | -0,02 | -0,02 | ||

| Rs3782905 | -0,08 | 0,53 | 0,55 | -0,44 | -0,45 | -0,45 | -0,33 | 0,05 | 0,05 | |||

| Rs2853563 | -0,14 | -0,16 | 0,20 | -0,10 | 0,19 | -0,01 | -0,07 | -0,08 | ||||

| Rs731236 | 0,98 | -0,76 | -0,69 | -0,46 | -0,32 | 0,07 | 0,05 | |||||

| Rs1544410 | -0,76 | -0,69 | -0,46 | -0,33 | 0,06 | 0,05 | ||||||

| Rs2239185 | 0,85 | 0,28 | 0,33 | -0,06 | -0,05 | |||||||

| Rs987849 | 0,22 | 0,40 | -0,02 | -0,01 | ||||||||

| Rs1540339 | 0,58 | -0,07 | -0,07 | |||||||||

| Rs2239186 | -0,11 | -0,11 | ||||||||||

| Rs1989969 | 0,98 |

Table 1.

Transmission disequilibrium of 13 VDR-SNPs in affected and unaffected children. P-values < 0.05 are indicated in bold.

| asthma | no asthma | |||||||||||||

| LD block * | dbSNP | allele | chr12 (bp) | geno-types | freq (%) | T | UT | T/UT | P | T | UT | T/UT | P | P TDTDS |

| A | hCV2880804 | C | 47954855 | 918 | 28 | 170 | 178 | 1,0 | 0,668 | 18 | 33 | 0,5 | 0,049 | 0,055 |

| -- | rs2228570 | T | 47977944 | 724 | 35 | 159 | 150 | 1,1 | 0,609 | 21 | 12 | 1,8 | 0,117 | 0,079 |

| ? | rs3819545 | C | 47981753 | 912 | 38 | 186 | 191 | 1,0 | 0,797 | 25 | 31 | 0,8 | 0,423 | 1,000 |

| B | rs3782905 | G | 47982914 | 934 | 32 | 201 | 174 | 1,2 | 0,163 | 26 | 27 | 1,0 | 0,891 | 0,388 |

| ? | rs2853563 | G | 48248398 | 661 | 97 | 20 | 24 | 0,8 | 0,547 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| B | rs731236 | C | 48251417 | 923 | 37 | 202 | 206 | 1,0 | 0,843 | 25 | 29 | 0,9 | 0,586 | 0,767 |

| B | rs1544410 | A | 48252495 | 896 | 37 | 190 | 186 | 1,0 | 0,837 | 23 | 26 | 0,9 | 0,668 | 1,000 |

| B? | rs2239185 | C | 48257219 | 903 | 49 | 198 | 214 | 0,9 | 0,431 | 29 | 24 | 1,2 | 0,492 | 0,650 |

| ? | rs987849 | C | 48267336 | 825 | 45 | 164 | 169 | 1,0 | 0,784 | 28 | 18 | 1,6 | 0,140 | 0,173 |

| B | rs1540339 | A | 48269986 | 916 | 36 | 189 | 187 | 1,0 | 0,575 | 25 | 27 | 0,9 | 0,782 | 0,706 |

| ? | rs2239186 | C | 48282070 | 929 | 19 | 116 | 145 | 0,8 | 0,073 | 20 | 18 | 1,1 | 0,746 | 0,189 |

| C | rs1989969 | T | 48290670 | 922 | 43 | 204 | 198 | 1,0 | 0,765 | 39 | 20 | 2,0 | 0,013 | 0,025 |

| C | rs2853564 | C | 48291147 | 920 | 44 | 196 | 201 | 1,0 | 0,802 | 38 | 20 | 1,9 | 0,018 | 0,021 |

*according to reference [15]

Finally, a 4-locus haplotype was constructed of those SNPs associated in the TDTDS. Again, no significant transmission distortion was found in affected children, while one haplotype showed a 5.1-fold over-transmission in unaffected children (P = 0.009).

Discussion

This study addresses a previously described association of VDR SNPs with asthma and related phenotypic traits. Although a preferential transmission of vitamin D receptor variants to children with asthma could not be confirmed, it raises the possibility of a protective effect in unaffected children. Although the effect is rather moderate, several SNPs support this association. If any, the association is probably more related to RNA turnover than to a structural modification of the receptor as there was no association with LD block "B" that codes for the translated exons. Gene expression can be varied over a 100-fold range by subtle modifications of the 3'-terminal sequence [15], which will requires further research on the function of these allelic variants in target tissues.

This notion is partially in contrast with a previous study of 7 VDR SNPs in the CAMP (Childhood Asthma Management Program) study of 582 nuclear families where SNP rs7975232 (akin ApaI) in intron 8 showed a highly significant effect [12]. A confirmation study by the same group in a case-control sample of the Nurses' Health Study NHS [12] also associated asthma with rs3782905 (intron 2, P = 0.02), rs2239185 (intron 3, P = 0.02) and rs731236 (Ile352Ile, P = 0.03). A study of 223 independent Canadian families reported six out of twelve SNPs to be associated with asthma (rs3782905, rs1540339, rs2239182, rs2239185, BsmI, ApaI, TaqI), most of these on block "B". As none of these SNPs was giving rise to an amino acid change the authors speculated about an intronic regulatory SNP or one or more functional variants at the 3' end of the VDR locus.

It is unlikely that increased or decreased vitamin D sensitivity is simply mediated by a genetic variation in the VDR. Vitamin D requires several enzymatic steps to be activated, transported and degraded; receptor signalling requires several co-factors and all of these may contribute additive or multiplicative effects on vitamin D sensitivity. The co-activator retinoic acid receptor RXR may itself affect Th1 and Th2 development [16]. Other transcription factors involved are SRC/p160, CBP and p300 [17]. The DRIP complex attaches to the VDR/RXR complex and binds to vitamin D responsive elements (VDRE) through histone acetyltransferase activity. Importantly, some of the vitamin D regulated genes are also located in allergy linkage regions. The renal 1-α-hydroxylase (12q13) and the 24-hydroxylase (20q13), as well as RXR (6p21), are all positional candidates. RXR has already been tagged by a SNP in a previous study [18] and also 3 SNPs in CYP24A1 (rs751089, rs2296241 and rs2248137) were significantly associated with asthma (unpublished own observation). CYP24A1 is particular interesting as it is the major enzyme of the degradation pathway that showed a 97-fold increase after vitamin D treatment of rats [19] or 12-fold increase in a human colon cancer cell line [20].

The number of genes regulated by vitamin D has been recently extended beyond those genes with known VDRE promoter motifs (calbindin, PTH, PTHRP, ITGB3, OC, GH, osteopontin, osteocalcin, c-fos, IL-2Rβ, NFκB, sCD23) to another 150 up- and down-regulated regulated genes [19-23]. The interaction of genetic variants in the VDR and other positional, as well as functional, candidate genes is therefore a current research topic. So far, only two gene associations have been published: Vitamin D binding protein (GC*2 and GC*1F) was associated with an increased risk for COPD [24,25] and osteopontin (OPN C8090T and T9250C) with increased total IgE in asthmatic patients [26].

In addition to its biological context, this study also has some implications on the statistical analysis as the rather low number of unaffected sibs seemed to contribute to a few positive associations. Despite enormous efforts to map complex genetic diseases, SNP association studies are often lacking power [27]. Linkage studies in affected sib pairs have been preferably used to map complex diseases to chromosomal regions [9], while "no substantial study of normal sib-pairs has been undertaken, making this family of surveys one of the largest undertaken in the absence of controls" [28] although unselected affected sib pairs tend to share more than half of their alleles [29]. This omission is even more remarkable as discordant sib pairs (DSP) have been shown to be a more powerful alternative [30]. Risch proposed to test DSP in the top ten and bottom ten percent distribution of quantitative traits, as pairs with intermediate values (between the 30th and 70th percentiles) did not provide much information for linkage analysis [31]. Although the DSP concept was appealing from a theoretical standpoint, it turned out that there are disadvantages for practical reasons. It requires a large amount of individuals to be screened, which might be the reason that the DSP approach has not received the expected attention except for a few studies (for a summary see [31]).

Transmission disequilibrium testing of unaffected child – parent trios originating from families with another two affected offsprings, may be a powerful alternative. As there is a strong ascertainment bias of these families toward a genetic risk, as well as a disease causing environmental factor, being unaffected is an extreme phenotype ("being sane in an insane world"). The transmission to unaffected children can be seen as an independent cross-match to the transmission to affected children. The high power of testing unaffected sibs has already been predicted on theoretical grounds [32]. The number of DSPs required to achieve 80% power (with a difference in the allele frequency of 15% and λs of 3.2) has been estimated to be approx. 250 [33]. A sample size of 1,500 families was estimated by including two affected and one unaffected children [34]. In this study already 50 DSPs were sufficient to show a significant distortion in the allele transmission. Non-paternity as a reason for discordant traits [35] is unlikely as nearly all families were included in a previous genome-wide scan.

Conclusions

The transmission disequilibrium in unaffected sibs in otherwise multiple-affected families seems to be a powerful test. A preferential transmission of vitamin D receptor variants to children with asthma could not be confirmed but raises the possibility of a protective effect in unaffected children.

Methods

Study population

The German asthma sib pair families were collected in 26 paediatric centres in Germany and Sweden for an initial genome-wide linkage scan. In these families at least two children were required with confirmed doctor-diagnosed asthma, while prematurity or low birth weight of the children were excluded, along with any other severe pulmonary disease. All affected children should have after their 3rd birthday a history of at least three years of recurrent wheezing and should not have any other airway disease diagnosed. Unaffected siblings were also sampled if they were at least 6 years old, eligible for pulmonary function testing and did not have doctor-diagnosed asthma.

On the first home visit a complete pedigree of the family was drawn and information collected in a questionnaire. Participants were examined for several associated phenotypes. Pulmonary function tests were performed by forced flow volume tests and bronchial challenge was done by methacholine.

Briefly, pulmonary function tests were performed by forced expiration in a sitting position using a nose-clip. Forced flow volume tests were performed until three reproducible loops were achieved. Of these the trial with the maximum sum of FVC and FEV1.0 was used for the analysis. Bronchial challenge with methacholine was done with increasing doses of 0, 0.156, 0.312, 0.625, 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, 25 mg/ml during 5 consecutive breaths with 14 mg delivered from a de Vilbiss 646 nebulizer chamber by using a breath-triggered pump ZAN 200 (Zan, Oberthulpa, Germany). The provocation was stopped either with the occurrence of symptoms or a fall of 20% from the baseline FEV1.0 and the slope of the dose-response curve calculated.

Total IgE was determined with an ELISA (Pharmacia Diagnostics, Uppsala, Sweden). The allergens tested were birch (betula verruscose) ALK SQ108, hazel (corylus avellana) ALK SQ113, the herbs ribworth (plantago lanceolata) ALK N342 and mugwort ALK SQ312, mixed grass ALK SQ299, dust mite dermatophagoides farinae ALK SQ 504, dermatophagoides pteronyssimus ALK SQ 503, cat dander ALK SQ555 and dog dander ALK SQ 553, and fungi (aspergillus fumigatus ALK N405 and alternaria alternata ALK N402), which were bought in one batch and stored at +5°C until analysis.

The original family collection [36] has been expanded since 1994 to a larger sample, of which 218 families were available in 2002 for a complete genome scan. The consecutive families were tested with the same protocol as described earlier [36] except that the time-consuming methacholine challenge protocol was omitted. Excluded from the final sample were individuals with incomplete data, missing DNA samples, identical twins and all probands with more than 2 non-segregating out of 408 microsatellite markers. Another 6 families could be included in this analysis, resulting in a final sample of 224 families. Each study participant, including all children, signed a consent form. All study methods were approved in 1995 by the ethics commission of "Nordrhein-Westfalen" and again in 2001 by "Bayerische Landesärztekammer München".

DNA preparation and genotyping

DNA was isolated from peripheral white blood cells using Qiamp (Qiagen, Germany) or Puregene isolation kits (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). From the VDR we selected 16 SNPs where 13 could finally be analyzed. They had to be polymorphic, complete, received a high calling score, passed paternity checks and were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. The following three markers have been excluded from the analysis: rs2239179 (contaminant in mass spectrum peak), rs2853559 (Hardy-Weinberg disequilibrium, paternity errors) and rs797523 (typing error in primer sequence).

Genotyping was performed using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry of allele-specific primer extension products (Table 3) generated from amplified DNA sequences (MassARRAY, SEQUENOM Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Primers were obtained from Metabion GmbH (Planegg-Martinsried, Germany).

Table 3.

Primer used for genotyping

| SNP | left primer | right primer | extension primer | stop mix |

| hCV2880804 | ACGTTGGATG-CTGGGATACTTCTGAGAGTG | ACGTTGGATG-TTTTCCCTGGAAAGTTTGGG | CCATTGTCCTGGTATAACCA | ACG |

| rs2228570 | ACGTTGGATG-TCAAAGTCTCCAGGGTCAGG | ACGTTGGATG-AGACCTCACAGAAGAGCACC | CCCTGCTCCTTCAGGGA | ACG |

| rs3819545 | ACGTTGGATG-AATGGTGGTTACTGCAGCTC | ACGTTGGATG-GAAACCAGTCCTCTGTCATG | TAGGTTCGGTCTTTGGCT | ACG |

| rs3782905 | ACGTTGGATG-GGGTCTCAAATTCTTAATGAG | ACGTTGGATG-AAACTAGCAGAAAGAGGCAG | GTGGGAGGGAGTGCTGA | ACT |

| rs2853564 | ACGTTGGATG-CTGCATTGCTCCTGACTTAG | ACGTTGGATG-AGGTAGCTTAGCTCTGAGTC | TTTCTGCAACCCTAAGCC | ACT |

| rs731236 | ACGTTGGATG-TGTGCCTTCTTCTCTATCCC | ACGTTGGATG-TGTACGTCTGCAGTGTGTTG | CGGTCCTGGATGGCCTC | ACT |

| rs1544410 | ACGTTGGATG-TAGATAAGCAGGGTTCCTGG | ACGTTGGATG-AATGTTGAGCCCAGTTCACG | AGCCTGAGTATTGGGAATG | ACG |

| rs2239185 | ACGTTGGATG-CAATTCCAGTCACATCTCGG | ACGTTGGATG-CCTGTGTGACATTTACACCC | CCCTCCTCTGTCTTCAC | ACT |

| rs987849 | ACGTTGGATG-GAATAGTGCCTTATAGATAG | ACGTTGGATG-AGCTAGAAGTTCTGGTGATC | GAAATATTCGTAATGCTGGAT | ACT |

| rs1540339 | ACGTTGGATG-TCACACACATTCTCAGTGGG | ACGTTGGATG-TTTGCAGAGGCTGTCTTCTC | GTTGGTGCCCACCCTAA | ACG |

| rs2239186 | ACGTTGGATG-GTCCACAGTGACTATAGACC | ACGTTGGATG-AAGAAGGAGAAGCAGGCATC | CAGGGGTGGAAGAAGAGGAG | ACT |

| rs1989969 | ACGTTGGATG-TGTATGCAGAGCTTAGCAGG | ACGTTGGATG-TTTCAGAGGTCAGAGGTGAC | GTCAGAGGTGACATCCAG | ACT |

| rs2853564 | ACGTTGGATG-CTGCATTGCTCCTGACTTAG | ACGTTGGATG-AGGTAGCTTAGCTCTGAGTC | TTTCTGCAACCCTAAGCC | ACT |

Data handling and statistical analysis

Clinical data and genotypes were transferred to a SQL 2000 database by using Cold Fusion 4.0 scripts. Statistical analyses were performed using R 1.8.1 [37] by accessing the database with the RODBC module. For each SNP, the distribution of genotypes in pseudo-controls created by combining the parental alleles not transmitted to asthma children was tested by a χ2-test as well as the transmission to their unaffected sibs. An extension of the classical TDT [34] was also implemented that incorporates effectively both affected and unaffected children (TDTDS). The standardized linkage disequilibrium coefficient D' and the correlation coefficient R2 were calculated for each pair of SNPs in parents by using the R package "genetics". All analyses were cross-checked by using SIBPAIR software. Haplotypes were estimated using TDTPHASED in the UNPHASED package [38] and transmission to affected and unaffected children tested separately. For phase-certain haplotypes a conditional logistic regression model was used, corresponding to the probability of the offspring conditional upon the parents. When phase was uncertain, unconditional logistic regression on the full likelihood of parents and offspring was used instead (see [39] for the formulations of these likelihoods). Transmitted haplotypes were compared to all untransmitted haplotypes, equivalent to the haplotype-based haplotype relative risk, while an EM algorithm was used to obtain maximum-likelihood estimates of case and control parental haplotype frequencies under both null and alternative hypotheses.

Abbreviations

VDR vitamin D receptor

VDRE vitamin D responsive element

SNP single nucleotide polymorphism

MALDI-TOF matrix assisted laser desorption ionisation – time of flight

DSP discordant sib pairs

TDT transmission disequilibrium

LD linkage disequilibrium

QTL quantitative trait locus

BHR bronchial hyperreactivity

FEV1 forced volume during the 1st second

Author's contribution

The author developed the idea presented in this paper, initiated the study, applied for funding, developed protocols, participated in the clinical survey, planned the laboratory analysis, did the statistical analysis, and drafted the report. This manuscript contains no patient identifiable information.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

I thank all participating families for their help and the members of the clinical centers for their work: R. Nickel, K. Beyer, R. Kehrt, U. Wahn (Berlin), K. Richter, H. Janiki, R. Joerres, H. Magnussen (Grosshansdorf), I. M. Sandberg, L. Lindell, N.I.M. Kjellman (Linkoeping), C. Frye, G. Woehlke, I. Meyer, O. Manuwald (Erfurt), A. Demirsoy, M. Griese, D. Reinhardt (München), G. Oepen, A. Martin, A. von Berg, D. Berdel (Wesel), Y. Guesewell, M. Gappa, H. von der Hardt (Hannover), J. Tuecke, F. Riedel (Bochum), M. Boehle, G. Kusenbach, H. Jellouschek, M. Barker, G. Heimann (Aachen), S. van Koningsbruggen, E. Rietschel (Köln), P. Schoberth (Köln), G. Damm, R. Szczepanski, T. Lob-Corzilius (Osnabrück), L. Schmid, W. Dorsch (München), M. Skiba, C. Seidel, M. Silbermann (Berlin), A. Schuster (Düsseldorf), J. Seidenberg (Oldenburg), W. Leupold, J. Kelber (Dresden), W. Wahlen (Homburg), F. Friedrichs, K. Zima (Aachen), P. Wolff (Pfullendorf), D. Bulle (Ravensburg), W. Rebien, A. Keller (Hamburg) and M. Tiedgen (Hamburg). I wish to thank M. Hoeltzenbein who helped start the study and J. Altmüller who managed the second part of the study, G. Schlenvoigt and L. Jaeger for IgE determination; former group members L. Thaller, G. Fischer, T. Illig, N. Klopp, C. Vollmert and M. Werner and doctoral students H. Gohlke, N. Herbon and G. Dütsch for their contribution in previous genotyping projects; P. Lichtner for administrative help; A. Jendretzke from Sequenom Inc. for technical support; M. Bahnweg, A. Luze, C. Braig and B. Wunderlich for excellent laboratory work. C. Braig did the genotyping reported here. The asthma family study was funded by BMBF 07ALE087, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft DFG WI621/5-1, DFG FR1526/1 and National Genome Network 01GS0122 (until 30th June 2004). I was funded by GSF FE 73922. Finally I wish to thank E. André and M. Emfinger for proof-reading of the manuscript; E. Hyppönen and B. Raby for helpful discussions on various aspects covered in this paper.

References

- Wjst M, Dold S. Genes, factor X and allergens. Allergy. 1999;54:757–759. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.1999.00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adorini L. Tolerogenic dendritic cells induced by vitamin D receptor ligands enhance regulatory T cells inhibiting autoimmune diabetes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;987:258–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb06057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheu V, Bäck O, Mondoc E, Issazadeh-Navikas S. Dual effects of vitamin D-induced alteration of TH1/TH2 cytokine expression: enhancing IgE production and decreasing airway eosinophilia in murine allergic airway disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:585–592. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(03)01855-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyppönen E, Sovio U, Wjst M, Patel S, Pekkanen J, Hartikainen AL, Järvelin MR. Vitamin D supplementation in infancy and the risk of allergies in adulthood: a birth cohort study. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Milner JD, Stein DM, McCarter R, Moon RY. Early infant multivitamin supplementation is associated with increased risk for food allergy and asthma. Pediatrics. 2004;114:27–32. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wjst M. The triple T allergy hypothesis. Clin Dev Immunol. 2004;11:175–180. doi: 10.1080/10446670410001722258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer CH. Vererbung und Rachitis : Eine medizin-geschichtliche Studie. Dissertation, Düsseldorf. 1938.

- Altmüller J, Palmer LJ, Fischer G, Scherb H, Wjst M. Genomewide scans of complex human diseases: true linkage is hard to find. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:936–950. doi: 10.1086/324069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike JW. In: The vitamin D receptor and its gene. Feldman D, Pike JW, Glorieux FH, editor. Vitamin D Academic Press; 1997. p. 105. [Google Scholar]

- Raby BA, Silverman EK, Lazarus R, Lange C, Kwiatkowski DJ, Weiss ST. Chromosome 12q harbors multiple genetic loci related to asthma and asthma-related phenotypes. Hum Mol Gen. 2003;12:1973–1979. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmert K, Illig T, Altmüller J, Klugbauer S, Loesgen S, Dumitrescu L, Wjst M. Single nucleotide polymorphism screening and association analysis – exclusion of integrin beta 7 (ITGB7) and vitamin D receptor (VDR) as candidate genes for asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Raby BA, Lange C, Silverman EK, Lake S, Lazarus R, Wjst M, Weiss ST. Association of vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism with childhood and adult asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:1057–1065. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200404-447OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon AH, Laprise C, Lemire M, Montpetit A, Sinnett D, Schurr E, Hudson TJ. Association of vitamin D receptor genetic variants. Am Rev Resp Crit Care Med. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nejentsev S, Godfrey L, Snook H, Rance H, Nutland S, Walker NM, Lam AC, Guja C, Ionescu-Tirgoviste C, Undlien DE, Ronningen KS, Tuomilehto-Wolf E, Tuomilehto J, Newport MJ, Clayton DG, Todd JA. Comparative high-resolution analysis of linkage disequilibrium and tag single nucleotide polymorphisms between populations in the vitamin D receptor gene. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1633–1639. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakoki M, Tsai YS, Kim HS, Hatada S, Ciavatta DJ, Takahashi N, Arnold LW, Maeda N, Smithies O. Altering the expression in mice of genes by modifying their 3' regions. Dev Cell. 2004;6:597–606. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(04)00094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata M, Eshima Y, Kagechika H. Retinoic acids exert direct effects on T cells to suppress Th1 development and enhance Th2 development via retinoic acid receptors. Int Immunol. 2003;15:1017–1025. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachez C, Freedman LP. Mechanisms of gene regulation by vitamin D(3) receptor: a network of coactivator interactions. Gene. 2000;246:9–21. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbon N, Werner M, Braig C, Gohlke H, Dütsch G, Illig T, Altmüller J, Hampe J, Lantermann A, Schreiber S, Bonifacio E, Ziegler A, Schwab S, Wildenauer D, van den Boom D, Braun A, Knapp M, Reitmeir P, Wjst M. High-resolution SNP scan of chromo-some 6p21 in pooled samples from patients with complex diseases. Genomics. 2003;81:510–518. doi: 10.1016/S0888-7543(02)00035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutuzova GD, Deluca HF. Gene expression profiles in rat intestine identify pathways for 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) stimulated calcium absorption and clarify its immunomodulatory properties. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;432:152–166. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood RJ, Tchack L, Angelo G, Pratt RE, Sonna LA. DNA microarray analysis of vitamin D-induced gene expression in a human colon carcinoma cell line. Physiol Genomics. 2004;17:122–129. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00002.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akutsu N, Lin R, Bastien Y, Bestawros A, Enepekides DJ, Black MJ, White JH. Regulation of gene expression by 1α, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and its analog EB1089 under growth-inhibitory conditions in squamous carcinoma cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:1127–1139. doi: 10.1210/me.15.7.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin R, Nagai Y, Sladek R, Bastien Y, Ho J, Petrecca K, Sotiropoulou G, Diamandis EP, Hudson TJ, White JH. Expression profiling in squamous carcinoma cells reveals pleiotropic effects of vitamin D3 analog EB1089 signaling on cell proliferation, differentiation, and immune system regulation. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:1243–1256. doi: 10.1210/me.16.6.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin MD, Xing N, Kumar R. DNA expression profiles in dendritic cells conditioned by 1α, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 analog. J Steroid Biochem Molc Biol. 2004;89–90:443–448. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laufs J, Andrason H, Sigvaldason A, Halapi E, Thorsteinsson L, Jonasson K, Soebech E, Gislason T, Gulcher JR, Stefansson K, Hakonarson H. Association of vitamin D binding protein variants with chronic mucus hypersecretion in Iceland. Am J Pharmacogenomics. 2004;4:63–68. doi: 10.2165/00129785-200404010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito I, Nagai S, Hoshino Y, Muro S, Hirai T, Tsukino M, Mishima M. Risk and severity of COPD is associated with the group-specific component of serum globulin 1F allele. Chest. 2004;125:63–70. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanino Y, Hizawa N, Fukui Y, Takahashi D, Maeda Y, Nishimura M. Ostepontin (OPN) gene polymorphism and total serum IgE levels in a Japanese population. Am Rev Resp Crit Care Med. 2004. Poster abstract D53, ATS, Orlando 21–26 May 2004.

- Ioannidis JP, Ntzani EE, Trikalinos TA, Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG. Replication validity of genetic association studies. Nat Genet. 2001;29:306–309. doi: 10.1038/ng749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J. Sib-pairs in multifactorial disorders: the sib-similarity problem. Clin Genet. 2003;63:1–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2003.630101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elston RC, Song D, Iyengar SK. Mathematical assumptions versus biological reality: Myths in affected sib pair linkage analysis. Am J Hum Gen. 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Risch N, Zhang H. Extreme discordant sib pairs for mapping quantitative trait loci in humans. Science. 1995;268:1584–1589. doi: 10.1126/science.7777857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szatkiewicz J, Cuenco KT, Feingold E. Recent advances in human quantitative-trait-locus mapping: Comparison of methods for discordant sibling pairs. Am J Hum Gen. 2003;73:874–885. doi: 10.1086/378590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng H-W, Chen W-M, Recke RR. Transmission disequilibrium test with discordant sibpairs when parents are available. Hum Gen. 2002;110:451–461. doi: 10.1007/s00439-002-0675-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehnke M, Langefeld CD. Genetic association mapping based on discordant sib pairs: the discordant-alleles test. Am J Hum Gen. 1998;62:950–961. doi: 10.1086/301787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W-M, Deng H-W. A general and accurate approach for computing the statistical power of the transmission disequilibrium test for complex genetic disease. Genetic Epidemiology. 2001;21:53–67. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC, Neale BM, Sullivan PF. Nonpaternity in linkage studies of extremely discordant sib pairs. Am J Hum Gen. 2002;70:526–529. doi: 10.1086/338687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wjst M, Fischer G, Immervoll T, Jung M, Saar K, Rueschendorf F, Reis A, Ulbrecht M, Gomolka M, Weiss EH, Jaeger L, Nickel R, Richter K, Kjellman NI, Griese M, von Berg A, Gappa M, Riedel F, Boehle M, van Koningsbruggen S, Schoberth P, Szczepanski R, Dorsch W, Silbermann M, Wichmann HE, and German Asthma Genetics Group A genome-wide search for linkage to asthma. Genomics. 1999;58:1–8. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria. 2003.

- Dudbridge F. Pedigree disequilibrium tests for multilocus haplotypes. Genet Epidemiol. 2003;25:115–121. doi: 10.1002/gepi.10252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton D. A Generalization of the transmission/disequilibrium test for uncertain-haplotype transmission. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:1170–1177. doi: 10.1086/302577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haussler MR, Jurutka PW, Hsieh J-C, Thompson P-D, Haussler CA, Selznick SH, Remus LS, Whitfield GK. In: Nuclear vitamin D receptor: structure-function, phosphorylation, and control of gene transcription. Feldman D, Pike JW, Glorieux FH, editor. Vitamin D Academic Press; 1997. p. 149. [Google Scholar]

- Mac Donald PN. Molecular biology of the vitamin D receptor. In: Holick MF, editor. Vitamin D: physiology, molecular biology, and clinical applications (nutrition and health) Humana. 1999. p. 109. [Google Scholar]