Abstract

Measurement of inappropriate medication use events (e.g., abuse, misuse) in clinical trials is important in characterizing a medication’s abuse potential. However, no “gold standard” assessment of inappropriate use events in clinical trials has been identified. In this systematic review, we examine the measurement properties (i.e., content validity, cross-sectional reliability and construct validity, longitudinal construct validity, ability to detect change, and responder definitions) of instruments assessing inappropriate use of opioid and non-opioid prescription medications to identify any that meet U.S. and European regulatory agencies’ rigorous standards for outcome measures in clinical trials. Sixteen published instruments were identified, most of which were not designed for the selected concept of interest and context of use. For this reason, many instruments were found to lack adequate content validity (or documentation of content validity) to evaluate current inappropriate medication use events; for example, evaluating inappropriate use across the lifespan rather than current use, including items that did not directly assess inappropriate use (e.g., questions about anger), or failing to capture information pertinent to inappropriate use events (e.g., intention, route of administration). In addition, the psychometric data across all instruments were generally limited in scope. A further limitation is the heterogeneous, non-standardized use of inappropriate medication use terminology. These observations suggest that available instruments are not well suited for assessing current inappropriate medication use within the specific context of clinical trials. Further effort is needed to develop reliable and valid instruments to measure current inappropriate medication use events in clinical trials.

Keywords: Abuse potential, misuse, clinical trial, measurement properties

Introduction

Research on prescription opioid analgesics suggests wide-ranging rates of abuse and addiction [24,29], from less than 1% in a non-peer reviewed letter to the editor focusing on post-operative pain medication abuse [49], to upward of 45% in a study of 20 patients with pain and a history of substance abuse [19]. Such heterogeneous estimates of abuse and addiction complicate the determination of the actual abuse risks associated with opioid analgesics. It is incumbent upon researchers to evaluate both analgesic benefit and the prevalence of distinct categories of current inappropriate analgesic use events (i.e., abuse events, misuse events, suicide-related events, and therapeutic errors [54]) in randomized clinical trials (RCTs) validly and reliably in order to accurately identify a treatment’s abuse potential (i.e., use for nonmedical psychoactive effects [59]). Capturing distinct inappropriate use events (i.e., behaviors indicating abuse, misuse, and other inappropriate medication use) in RCTs assists in evaluating a property of the drug (i.e., its abuse potential), rather than identifying clinical conditions in the users (e.g., drug use disorder). The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) emphasize collecting data on the occurrence of abuse, misuse, and diversion, in phase 3 clinical trials of centrally acting drugs [59] and analgesic clinical studies [22]. Information on these events is then evaluated in combination with other relevant data (e.g., pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics, human abuse potential studies in recreational drug users) to determine a treatment’s abuse potential [59]. Currently, neither FDA nor EMA recommend any instruments to assess inappropriate medication use as an outcome in clinical trials requiring regulatory review, although available FDA guidances and EMA reflection papers present recommendations for developing patient-reported outcome instruments and qualifying drug development tools [21,58,60].

Unlike prior reviews [5,14,46,47], we explore whether available inappropriate use instruments fulfill regulatory standards by providing evidence of content validity (i.e., “Evidence that the instrument measures the concept of interest including evidence from qualitative studies that the items and domains of an instrument are appropriate and comprehensive relative to its intended measurement concept, population, and use” p.11 [58]) for assessing a selected concept of interest (i.e., “…the thing being measured…” p.2 [58]) within a specific context of use (i.e., “…the intended application in terms of population, condition, and other aspects of the measurement context for which the instrument was developed.” p.20 [58]). For the purposes of this review, the concept of interest and context of use is current inappropriate use event categories (i.e., abuse events, misuse events, suicide-related events, and therapeutic errors occurring in clinical trials [i.e., phases 2 and 3], as defined by the Analgesic, Anesthetic, and Addiction Clinical Trial Translations, Innovations, Opportunities, and Networks [ACTTION] public-private partnership [54]). Further, we examine whether the instruments provide sufficient data regarding cross-sectional reliability and construct validity, as well as longitudinal construct validity (i.e., hypothesized relationships between concepts over time [58]), ability to detect change, and responder definitions, to meet regulatory standards for assessing benefits and risks in clinical trials [21,58,60]. We do not review measures for abuse liability assessment in early phase studies with substance abusers [16] or those designed to predict the development of inappropriate medication use [14,57]. It is important to acknowledge that most instruments reviewed were developed for other purposes (e.g., diagnosis of substance use disorders), rather than identifying current inappropriate medication use events occurring in clinical trials. These instruments, many of which might appear suitable to measure inappropriate medication use, were included in this review to evaluate their applicability to the specific concept of interest and context of use, a necessary first step in developing an instrument that is valid for the selected concept and context. Our comments on the appropriateness of each instrument for the specified concept and context should not be taken to refer to each instrument’s appropriateness for evaluating other concepts (e.g., patient risk of developing a drug use disorder) in different contexts (e.g., clinical practice).

Methods

Literature search

We conducted an initial systematic search (search #1) of the US National Library of Medicine database (PubMed; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) using the following algorithm: “(current OR prescription) AND (drug OR medication) AND (nonmedical OR aberrant OR misuse OR abuse OR addiction) AND (self-report OR scale OR measure OR instrument OR assessment OR questionnaire OR index).” These search terms were chosen based on the content of relevant review articles identified by the authors in an attempt to include all articles that described instruments to evaluate inappropriate medication use or the measurement properties of an inappropriate medication use instrument. In order to select instruments currently in use, the search was restricted to publications in English from January 1, 2000 to October 31, 2013. Articles were included if they reported on instruments to assess current nonmedical use, aberrant behaviors, misuse, abuse, or addiction associated with prescription drugs. Articles were excluded if the reported instrument consisted of a single question or solely assessed (1) inappropriate use of non-prescription drugs (i.e., illicit drug abuse); (2) inappropriate use of prescription drugs across an individual’s lifetime, which is suggestive of an individual’s drug use disorder or risk of drug use disorder, rather than specifically indicating a treatment’s abuse potential; (3) risk factors associated with inappropriate prescription drug use; (4) signs and symptoms of inappropriate use for the purpose of diagnosing substance abuse disorders (e.g., criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd or 4th editions [DSM-III or DSM-IV]); (5) symptom intensity (e.g., dependence or withdrawal); or (6) phenomena associated with prescription drug use that do not necessarily indicate current inappropriate use (e.g., assessment of drug liking or craving).

In addition, relevant original papers and reviews obtained from the initial PubMed search were examined for references to current inappropriate use instruments. A manual search of the present authors’ personal libraries was also conducted to gather any additional articles reporting the development of instruments assessing current inappropriate prescription drug use. If a previously unidentified instrument was found with either method, a PubMed search of the instrument’s name was performed to ensure identification of the publication that first described or developed the instrument; such articles could be older than year 2000.

For each instrument identified (see Electronic Table 1), we conducted 2 additional PubMed searches (search #2) for measurement properties (i.e., content validity, reliability, construct validity, ability to detect change, and responder definitions) (1) using the name of each instrument as a search term, and (2) reviewing up to 40 citations related to the article that first described each instrument (i.e., using PubMed’s “Related Citation” tool). We further searched Thomson Reuters Web of Knowledge (www.webofknowledge.com) for articles citing each instrument’s original publication. All retrieved articles were reviewed for measurement properties, excluding articles that validated a foreign language version of an instrument. Only published information on the instruments and their measurement properties were included; authors of instruments were not contacted to obtain unpublished information.

Regulatory standards for instrument qualification

FDA guidance and EMA guidance and reflection papers were searched for recommendations regarding the steps necessary to label an instrument as valid and psychometrically sound for use in medication clinical trial [21,22,58,60]. These guidance documents emphasize the importance of content validity, as well as cross-sectional data on reliability (i.e., test-retest and inter-rater) and construct validity (i.e., the relationships between the instrument and other concepts match pre-specified predictions), and longitudinal construct validity, ability to detect change, and the determination of clinically meaningful change (i.e., a responder definition)[21,22,58,60]. For each inappropriate use instrument, we identified any measurement properties that were presented, as well as the instrument’s ability to distinguish between distinct categories of inappropriate use events, with a focus on content validity. The FDA guidance on patient reported outcomes emphasizes the necessity of establishing an instrument’s content validity, including the appropriateness of all items, to assess the concept of interest within the context of use before evaluating other measurement properties [58]. Items that are related to the concept of interest (e.g., items that predict inappropriate use events) may be useful for identifying other concepts of interest (e.g., risk of inappropriate use), but do not directly measure the actual occurrence of inappropriate use events, thereby undermining an instrument’s content validity for assessing inappropriate use events. Demonstration of content validity involves literature review and expert input in item generation, but also requires patient input about the items [58; http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DrugDevelopmentToolsQualificationProgram/UCM370175.pdf]. This ensures that the instrument “measure[s] the concept represented by the labeling claim” (p.12 [58]). Content validity was evaluated by the first author to determine how well each instrument assessed current inappropriate use events occurring in clinical trials and was reviewed by all other authors.

Results

Search results

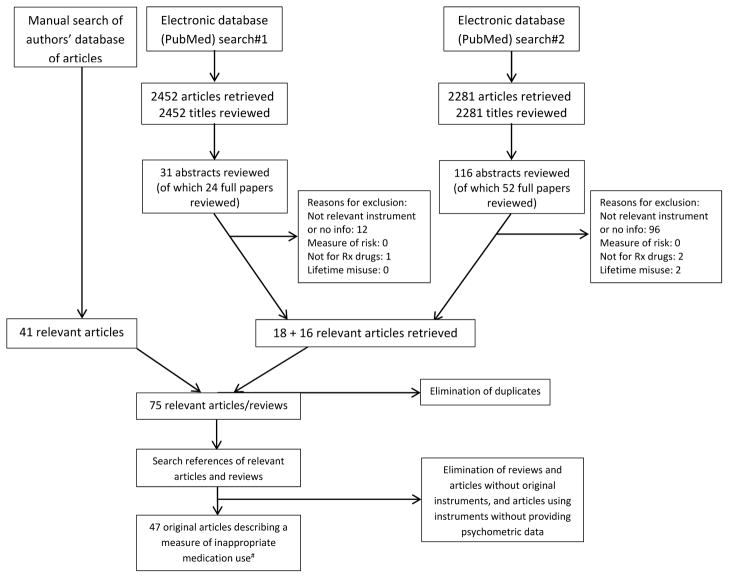

Search #1 retrieved 2452 articles and Search #2 retrieved 2281 articles. Examination of the present authors’ internal libraries identified 41 relevant articles. The publication screening process is described in Figure 1. A brief description of each of the 16 qualifying instruments is provided in Electronic Table 1, with instruments organized into the following categories: (1) patient-reported instruments: non-specific; (2) patient-reported instruments: opioid specific; (3) clinician-reported instruments: non-specific; (4) clinician-reported instruments: prescription drug specific; (5) clinician-reported instruments: opioid specific; and (6) composite instruments. Within each category, the instruments are presented in chronological order of publication. The original instruments are provided in the appendices by permission from the copyright holders (permission to reprint was not granted for two instruments, which therefore do not appear in the appendices). Table 1 presents the available measurement properties for each of the 16 instruments identified. Summaries of each instrument are provided below.

Figure 1.

Article selection

# Includes papers describing original or shortened versions of the instruments, which may be older than 2000.

Table 1.

Psychometric data for the evaluated instruments

| Instrument Evaluated (less recent to most recent) | Reference | Population (n) | Measurement Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient-Reported Instruments (self-report) | |||

| Non-specific | |||

| DAST | Skinner, 1982 [52] | Pts seeking help for inappropriate drug or alcohol use (n=223) | Internal consistency: α = 0.92. Statistically significant differences in DAST scores between participants with (1) only drug problems, (2) those with drug and alcohol problems, and (3) only alcohol problems, with participants in group 1 demonstrating the highest DAST scores, followed by group 2, then group 3. DAST scores positively and significantly correlated with frequency of drug use over 12 months and psychopathology. |

| Skinner & Goldberg, 1986 [53] | Pts seeking help for inappropriate opiate use (n=105) | DAST-20: Concurrent correlation between DAST and self-identified narcotics problem: r = 0.30. Principal components analysis yielded 5 factors, accounting for 55% of the variance. | |

| Gavin et al., 1989 [25] | Pts seeking help for drug or alcohol use (n=501) | DAST-20: Strong concurrent correlations between DAST and current and lifetime DSM-III drug addiction diagnoses = 0.75 and 0.74, respectively, and between DAST and number of DSM-III drug-related symptoms in the past month. Moderate concurrent correlations between DAST and number of drug use days in the past week and number of drugs used in the past week. Small concurrent correlations between DAST and psychological health. Small and generally negative concurrent correlations with measures of alcohol use and abuse. ROC analysis yielded AUC of 0.93 (criterion is DSM-III drug abuse/dependence diagnosis). ROC analysis indicated cutoff score of “5/6” was optimal, yielding sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 79%. | |

| Staley & El-Guebaly, 1990 [55] | Pts in psychiatric treatment programs (n=250) | Internal consistency: α = 0.94. Statistically significant differences in DAST scores between participants (1) with DSM-III substance abuse diagnoses in an outpatient substance abuse program and those in the (2) inpatient psychiatric program, (3) outpatient anxiety disorder program, and (4) day hospital. 75% of the participants in (1) had a DAST score of ≥ 6, compared to 28% in (2), 13% in (3), and 18% in (4). Principal components analysis yielded 5 factors accounting for 64% of the variance. | |

| Kemper et al., 1993 [30] | Mothers of children < 6 in pediatric clinics (n=507) | DAST-20: Mothers who indicated they used drugs within the past 24 hours were not identified by the DAST. | |

| Saltstone et al., 1994 [50] | Females on probation or incarcerated (n=615) | DAST-20: Internal consistency: α = 0.88. Initial principal components analysis yielded 5 factors; 1 factor accounted for <1% of the variance, leading to a principle components analysis constrained to 4 factors that accounted for 56% of the variance. Including DAST items and alcohol abuse items into a principal components analysis demonstrated that DAST items loaded independently. | |

| El-Bassel et al., 1997 [20] | Participants in an employee assistance program (n=176) | Internal consistency: α = 0.92. 2 week test-retest reliability in 20 participants: r = 0.85. Principal components analysis (using 26 of 28 items) yielded 5 factors, accounting for 63% of the variance. 93% of self-reported current drug users scored ≥ 6 on the DAST; 74% of self-reported former users scored ≥ 6; 6% of self-reported non-users scored ≥ 6. |

|

| Cocco & Carey, 1998 [15] | Psychiatric outpatients (n=97) |

DAST-10: Internal consistency: α = 0.86. 3–10 day test-retest reliability: ICC = 0.71. Principle components analysis yielded 3 factors, accounting for 64% of the variance. Moderate concurrent correlations with questions related to drug use. Cutoff scores between 1 or 2 and 3 or 4 were associated with acceptable to high sensitivity levels, but low to acceptable specificity levels (criterion is DSM-III-R drug use disorder diagnosis). DAST-20: Internal consistency: α = 0.92. 3–10 day test-retest reliability: ICC = 0.78. Principle components analysis yielded 6 factors, accounting for 71% of the variance. Moderate concurrent correlations with questions related to drug use. Individuals with current drug abuse diagnosis had significantly higher DAST scores than those with a prior drug abuse diagnosis or no history of drug abuse. Cutoff scores between 2 or 3 and 5 or 6 were associated with acceptable to high sensitivity levels, but low to acceptable specificity levels (same criterion). |

|

| Maisto et al., 2000 [32] | Outpatients with serious persistent mental illness (n=162) | DAST-10: A cutoff score of 2 resulted in sensitivity of 85% and specificity of 78% (criterion is current drug use disorder diagnosis using DSM-IV criteria). | |

| Martino et al., 2000 [36] | Adolescent psychiatric inpatients (n=194) | DAST-A: Internal consistency: α = 0.91. 1 week test-retest reliability: r = 0.89. Adolescents with drug dependency diagnoses scored significantly higher on the DAST-A than adolescents who abused drugs, abused or were dependent on alcohol, or had no substance use diagnoses. Principle components analysis yielded 1 “meaningful” factor which accounted for 32% of the variance. A cutoff score of > 6 was associated with sensitivity of 70–79% (criterion is DSM-III-R and DSM-IV drug-related disorders, respectively) and specificity of 82–84% (DSM-III-R and DSM-IV, respectively). | |

| McCann et al., 2000 [37] | Pts at an ADHD clinic (n=143) | Internal consistency: α = 0.92. Individuals with current or past drug use disorders scored significantly higher on the DAST than individuals without a history of problematic drug use. A cutoff score of 6 was associated with 85% sensitivity and 71% specificity (criterion is drug abuse or dependence using DSM-IV criteria). | |

| Carey et al., 2003 [11] | Inpatients in an Indian psychiatric hospital (n=1349) | DAST-10: Internal consistency: α = 0.94. Factor analysis supported 1 factor which accounted for 94% of the variance. Patients receiving treatment for addiction had significantly higher DAST scores than other patients. | |

| Cassidy et al., 2008 [12] | Individuals experiencing their first psychotic episode (n=112) | DAST-20: Internal consistency: α = 0.99. Median DAST scores were significantly higher among patients diagnosed with drug abuse or dependence and misuse within the past year than among patients without a drug use disorder diagnosis. The conventional cutoff score of 6 was associated with 55% sensitivity and 86% specificity (criterion is drug misuse diagnosis using DSM-IV criteria), although a cutoff score of 3 was associated with 85% sensitivity and 73% specificity. ROC analysis yielded AUC of 0.83 (same criterion). | |

| Møller & Linaker, 2010 [43] | Individuals with mental illness involving psychosis in Norway (n=48) | DAST-20: A cutoff score of 5 was associated with sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 67% using ICD-10 substance abuse diagnosis as the criterion (phi-coefficient = 0.41). A cutoff score of 5 was associated with 74% sensitivity and 66% specificity using the staff-reported Clinical Drug Use Scale (DUS) as the criterion (phi-coefficient = 0.34). | |

Summary – DAST

Summary – DAST-10

Summary – DAST-20

Summary – DAST-A |

|||

| Opioid-specific | |||

| COMM | Butler et al., 2007 [7] | Chronic noncancer pain pts from hospital and pain management centers currently taking opioids (n=227) | Experts who work with chronic pain patients (i.e., primary care physicians, nurses, psychologists, pain specialists, and addiction specialists) brainstormed about signals that a patient on opioids is exhibiting aberrant opioid use behaviors. This list was reduced by asking an independent group of experts to sort and rate the importance of each signal, the data from which were entered into a multidimensional scaling software program. The importance and wording of individual items was then evaluated by a 3rd group of experts. The final 17 items were identified by examining the psychometric properties among the 227 current pain patients taking opioids. Internal consistency: α = 0.86. 1 week test-retest reliability: ICC = 0.86. Two ROC analyses yielded AUC from 0.81–0.92 (criterion is ADBI). Cutoff score of 9 yields sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 73%; cutoff score of 10 yields sensitivity of 84% and specificity of 82% (same criterion). Reassessed 86 participants 3 mo after initial assessment to look at responsiveness; COMM detected 29 of 31 who were misusing (same criterion). |

| Butler et al., 2010 [6] | Pts recruited from pain management centers taking opioids (n=226) | Internal consistency: α = 0.83. ROC analysis yielded AUC of 0.79 (criterion is ADBI). Cutoff score of ≥ 9 yields sensitivity of 71% and specificity of 71% (same criterion). | |

| Meltzer et al., 2011 [41] | Primary care pts with chronic pain (n=238) | Significantly higher COMM score in pts with prescription drug use disorder than those without. ROC analysis yielded AUC of 0.84 (criterion is DSM-IV prescription drug use disorder). Cutoff score of ≥ 13 yields sensitivity of 77% and specificity of 77% (same criterion). | |

| Finkelman et al., 2013 [23] | Same data as Butler 2007, Butler 2010 | Various stopping rules result in sensitivity ranging from 69–70% and specificity ranging from 70–72% (criterion is ADBI); sensitivity ranging from 96–100% and specificity ranging from 99–100% (criterion is full COMM). | |

Summary

| |||

| PODS-CS | Banta-Green et al., 2010 [4] | Pts prescribed opioids for chronic pain (n=1144) | Items identified from prior interviews with pain patients regarding problems and concerns about their chronic opioid therapy, input from 2 expert clinicians, and literature review. Internal consistency (original 0–5 scale): αs range from 0.75–0.79. Internal consistency (recoded scoring): αs range from 0.63–0.65. |

| Sullivan et al., 2010 [56] | Same data as Banta-Green 2010 | PODS-CS not significantly related to past 3 mo average pain intensity, although there was a small association with pain interference (r = 0.09) and a moderate relationship with depression. Odds ratio of prior drug use disorder diagnosis significantly higher in pts with mid-range or high scores on PODS-CS than those with low scores. | |

Summary

| |||

| [no name] 20 aberrant drug-related behaviors | Hansen et al., 2011 [26] | HIV pain pts on chronic opioid therapy (n=296) | Items identified from a literature review and input from clinicians. |

Summary

| |||

| [no name] 8-item opioid analgesic misuse instrument | Jeevanjee et al., 2013 [28] | Homeless HIV pain pts prescribed antiretroviral drugs (n=258) | Opioid misuse in past 90 days was associated with significantly lower adherence to antiretroviral medication. |

Summary

| |||

| Clinician-Reported Instruments | |||

| Non-specific | |||

| ASI, 5th edition | McLellan et al., 1992 [38] | Pts in detoxification and drug rehabilitation programs (n=42) | Pilot tested the new additions in the ASI 5th edition to ensure items and instructions were understood. |

| Butler et al., 2001 [9] | Pts in substance abuse treatment (n=202) | Multimedia version (ASI-MV): Drug use composite score has good 3–5 day test-retest reliability and good criterion validity against 5th edition ASI. Convergent and discriminant validity for drug use composite score generally superior to 5th edition ASI drug use composite score. | |

| Mäkelä, 2004 (review of 37 studies) [33] | Analysis of ASI performance in 37 studies | In a review of 37 studies, the drug use composite score demonstrates low inter-rater and test-retest reliabilities, low criterion validity, and variable internal consistency, sensitivity, and specificity. | |

| Cacciola 2007 | Pts in substance abuse treatment from an outpatient clinic and a methadone maintenance clinic (n=145 + 50) | Shortened “lite” version (ASI-L-VA): Internal consistency was low for the drug use composite score in both the ASI-L-VA and the ASI 5th edition. | |

Summary - ASI 5th edition

Summary – ASI-MV | |||

| Prescription drug-specific | |||

| AIA | Adams et al., 2006 [1] | Chronic pain pts beginning treatment with tramadol, hydrocodone, or NSAIDs (n=11,352) | Items identified from addiction behaviors in American Academy of Pain Management (AAPM), American Pain Society (APS), and American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) consensus statement, DSM-IV-TR abuse and dependence classifications, with literature review, input from steering committee, and pilot testing with 30 patients. Hydrocodone pts had significantly more positive scores on the AIA than pts taking tramadol or NSAIDs |

Summary

| |||

| Opioid-specific | |||

| POAC | Chabal et al., 1997 [13] | Pain pts enrolled in a pain clinic on chronic opioid therapy (n=76) | Experts working with chronic pain patients developed the instrument. Inter-rater reliability = 0.90. |

Summary

| |||

| PDUQ | Compton et al., 1998 [17] | Pain pts receiving chronic opioid therapy referred from a multidisciplinary pain center for “problematic” medication use (n=52) | Items based on literature review, review of medical records of chronic pain patients with addiction. Designed to meet ASAM and DSM-IV criteria for addiction. Internal consistency: α = 0.81. Nonaddicted participants had significantly lower PDUQ scores than substance abusing and substance dependent participants. |

| Butler et al., 2007 [7] | Chronic noncancer pain pts currently taking opioids from hospital and pain management centers (n=227) | Internal consistency: α = 0.79. | |

| Wasan et al., 2009 [62] | Pain pts currently on chronic opioid therapy (from pain management centers) (n=455) | Pts who reported craving had significantly higher PDUQ scores than those who reported no craving. | |

| Compton et al., 2008 (self-report version, PDUQp) [18] | Pts with chronic pain from a multidisciplinary VA chronic pain clinic (n=135) | Concurrent correlation btw PDUQp and PDUQ = 0.64. Baseline PDUQp demonstrated moderate predictive validity with PDUQ at 4, 8, and 12 mo. PDUQp has moderate test-retest reliability at 4, 8, and 12 mo. Cutoff score of ≥ 10 has sensitivity of 66.7% and specificity of 59.7% in predicting discontinuation of study due to medication agreement violation. | |

| Banta-Green et al., 2009 (15-item PDUQ) [3] | Pain pts on chronic opioid therapy from an HMO database - general medical setting (n=704) |

Original PDUQ: Internal consistency is poor (Cronbach’s α = 0.56). 15-item PDUQ: Factor analysis shows the 15 items loaded onto 3 factors which were distinct from items measuring DSM-IV dependence and abuse. |

|

Summary - PDUQ

Summary - PDUQp

Summary – 15-item PDUQ

| |||

| Screening evaluation tool for controlled substance abuse | Manchikanti et al., 2003 [35] | Pts prescribed controlled substances in a pain management center (n=500) | Items identified using a literature review. Total score ≥ 2 on screening tool correctly identified 90% of pts with history of drug abuse; only 3% of pts without drug abuse history scored ≥ 2. |

| Manchikanti et al., 2004 [34] | Pts prescribed controlled substances in a pain management center (n=150) | Total score ≥ 2 on screening tool correctly identified 79% of pts with controlled substance abuse (regardless of illicit drug use); only 2% of pts without substance abuse scored ≥ 2. | |

Summary

| |||

| POTQ | Michna et al., 2004 [42] | Chronic pain pts taking opioids (n=145) | Significantly higher POTQ scores in participants at high risk of drug and alcohol abuse than low risk participants |

| Wasan et al., 2009 [62] | Pain pts currently on chronic opioid therapy (from pain management centers) (n=455) | Pts who reported craving had significantly higher POTQ scores than those who reported no craving. | |

Summary

| |||

| PADT | Passik et al., 2004 [48] | Pain pts on chronic opioid therapy (n=388) | Items identified using literature review, input from pain and addiction experts, and feedback from implementing clinicians. |

Summary

| |||

| ABC | Wu et al., 2006 [63] | Veterans in a Veterans Affairs Chronic Pain Clinic on chronic opioid therapy (n=136) | Items based on literature review; designed to meet AAPM, APS, ASAM criteria for addiction. Inter-rater reliability: rs from 0.94–0.95. Pts whose clinician categorized them as inappropriately using medications scored significantly higher on the ABC than pts whose clinician categorized them as appropriately using medications. Correlation with the PDUQ: r = 0.40. Cut-off score of ≥ 3: Sensitivity = 87.5% specificity = 86.1% in predicting clinician categorization as inappropriate or appropriate medication user. Participants who were discontinued from study due to inappropriate medication use had significantly higher mean ABC score at last study visit than participants who remained in the study. |

Summary

| |||

| POMI | Knisely et al., 2008 [31] | Pain pts prescribed OxyContin & pts treated for OxyContin addiction (n=74) | ROC analysis comparing POMI score and DSM-IV opiate diagnosis yielded an AUC of 0.89. POMI cutoff score of ≥ 2 demonstrates sensitivity = 82% and specificity = 92% (same criterion). |

Summary

| |||

| Composite Instruments | |||

| ADBI | Wasan et al., 2009 [62] | Pain pts currently on chronic opioid therapy (from pain management centers) (n=455) | Pts who scored positively on the ADBI were significantly more likely to report craving than to report no craving. |

Summary

| |||

| DMI | Jamison et al., 2010 [27] | Chronic back or neck pain pts from a pain management clinic currently on opioid therapy (n=228) | At the end of the 6 month study, 73.7% of pts at high risk for inappropriate opioid use who did not undergo medication counseling scored highly on the DMI, compared to 26.3% of high-risk pts who underwent counseling and 25.0% of low-risk control participants. |

Summary

| |||

Abbreviations: AUC = area under curve; Pts = patients; ROC = receiver operating curve.

Measurement properties: (1) content validity; (2) cross-sectional reliability (test-retest, inter-rater); (3) cross-sectional construct validity; (4) longitudinal construct validity; (5) longitudinal ability to detect change; (6) longitudinal determination of clinically meaningful change or responder definitions.

Articles that did not provide psychometric data are not included in this table.

Patient-reported instruments: non-specific

Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST)

The 28-item, self-report DAST was created to evaluate problems associated with prescription, over-the-counter, and illicit drug use (Appendix A; [52]). DAST items were developed to parallel questions in the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST; [51]), and it has been frequently used in the literature on inappropriate medication use. With respect to general content validity, no information was provided regarding whether qualitative research (i.e., input from patients or experts, or a literature review) was conducted to ensure the appropriateness of the DAST questions to assess drug abuse. Inspection of the DAST items also reveals that not all are content valid for the specific context of use addressed by this review (i.e., measuring current inappropriate medication use in clinical trials). Many items focus on an individual’s lifetime history of inappropriate use (i.e., “Do you ever…” or “Have you ever…”), which may provide useful contextual information when determining whether an event in an RCT is an inappropriate use event and how to classify it. However, history of inappropriate use is not an event in and of itself. One item asks about withdrawal symptoms, which are not necessarily indicative of inappropriate use, but are a normal physiologic reaction to the removal of a drug with effects on the central nervous system or the administration of a drug antagonist [44,45]. Additionally, the DAST does not capture information such as the intention underlying the inappropriate use, or the route of administration, details which are necessary for classifying events into distinct inappropriate use categories.

The internal reliability of the DAST has been demonstrated to be high in individuals with inappropriate drug use, psychiatric patients, and individuals in an employee assistance program (Table 1; [20,37,52,55]). In a small group of participants in an employee assistance program, El-Bassel et al. [20] found a high test-retest correlation over 2 weeks. A number of studies have demonstrated the validity of the DAST. For example, across 3 studies, DAST scores were significantly higher among individuals with problematic drug use than individuals without such use [37,52,55]. Further, Skinner [52] showed that DAST scores were correlated with drug use frequency over 1 year. DAST scores of 6 or more were associated with drug use disorders [55], as well as demonstrating good sensitivity and moderate specificity when a diagnosis of drug use disorder was the criterion [37].

Two short forms, the DAST-10 and the DAST-20, have each shown high internal consistency [11,12,15,50], as well as convergent validity with small to large correlations with other measures of inappropriate medication use and frequency of drug use [11,12,15,25,53]. Results of one study indicated that DAST-20 items loaded independently of alcohol abuse items [50], which can be considered evidence of discriminant validity. The sensitivity and specificity of the DAST-10 and the DAST-20 using drug use disorder diagnoses as the criteria have varied from low to high, although the studies have used various cutoff scores [12,15,25,32,43]. Further, a study of mothers of children in a pediatric practice demonstrated that the DAST-20 failed to identify mothers who used drugs inappropriately within the past 24 hours [30]. One publication on the DAST-A, a version developed for use in adolescent psychiatric inpatients, demonstrated high internal consistency and 1 week test-retest reliability; adolescents with drug dependency diagnoses scored more highly on the DAST-A than did other groups demonstrating its validity, and showed that a cutoff score above 6 was associated with moderate sensitivity and good specificity in predicting DSM-III-R and DSM-IV drug-related disorders [36]. To our knowledge, no data are available to evaluate its longitudinal construct validity, its ability to detect change in inappropriate medication use, or what constitutes clinically important within-person change.

Patient-reported instruments: opioid specific

Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM)

The COMM is a 17-item self-report instrument designed to “assess a patient’s current misuse of opioids” (p 145) by asking about social, emotional, and functional problems, as well as behaviors related to inappropriate medication use (Appendix B; [7]). Pain and addiction specialists, as well as primary care staff, created a list of items, which were sorted by a separate group of experts into 6 clusters with the highest ranked items from each cluster included in the initial version of the COMM (40 items). Psychometric evaluation narrowed the final item list to 17 [7]. Patient input on the COMM items was not obtained, nor was a literature review reported. Not all items directly evaluate current inappropriate medication use, as well, limiting the COMM’s content validity for this specific context of use. For example, there are items that examine the respondent’s functional difficulties (e.g., “How often have you had trouble with thinking clearly or had memory problems?”; “How often do people complain that you are not completing necessary tasks?”) and emotional volatility (e.g., “How often have you been in an argument?”; “How often have you had trouble controlling your anger?”; Appendix B). These contextual items may provide additional details that help to classify inappropriate use events, but they themselves are not current inappropriate medication use events. Further, information that is necessary to distinguish between inappropriate use events is not collected in the COMM.

Two studies have demonstrated the COMM’s high internal reliability in patients with chronic pain recruited from pain management centers who have opioid prescriptions (Table 1; [6,7]. The area under the curve in Receiver Operating Characteristic analyses using different “gold standard” criteria for classifying inappropriate medication use, as well as patients with chronic pain recruited from different clinical settings, have likewise been high [6,7,41]. One study demonstrated the COMM’s ability to detect change in misuse status after 3 months [7]. In 2 studies, sensitivity and specificity were maximized with a cutoff score of ≥ 9 out of 68 [6,7], whereas a higher cutoff score of ≥ 13 out of 68 maximized these values in a third study [41]. Meltzer et al. [41] also found higher COMM scores in patients with chronic pain who had a prescription drug use disorder than those participants who were not so diagnosed, supporting the construct validity of the instrument.

Shortened versions of the COMM have also been explored. Using retrospective data from the initial development of the COMM [6,7], Finkelman and colleagues [23] created computerized versions of the COMM that reduced the number of items presented to respondents based on respondents’ answers to the initial COMM items and estimates of the likelihood that the respondents will reach the ≥ 9 cutoff score for opioid misuse. These shortened versions demonstrate excellent sensitivity and specificity with the full-length COMM as the criterion, but moderate sensitivity and specificity when using the Aberrant Drug Behavior Index (ADBI; [23]). We were unable to identify data on its longitudinal construct validity or definitions of clinically important within-person change.

Prescribed Opioid Difficulty Scale-Concern Scale (PODS-CS)

The PODS-CS is a 7-item self-report instrument derived from the Prescription Drug Use Questionnaire (PDUQ, described in section 3.6.2 below; [17]) that assesses patients’ concerns regarding their patterns of use of prescription opioids (Appendix C; [4]). Instrument creation involved identifying concerns raised by patients during interviews, as well as a literature review and input from 2 experts. For the specific context of use that is the focus of this review, however, this instrument has limited content validity. Six of the 7 items ask participants to consider their concerns over the past year, in addition to a focus on worries about use of opioid analgesics rather than evaluating the presence of inappropriate use. Details that are pertinent to inappropriate use events are not collected, as well.

Internal consistency for this instrument ranged from poor to acceptable, depending on how responses were coded [4]. Sullivan et al. [56] reanalyzed the Banta-Green et al. [4] data to examine concurrent relationships with other measures, finding a moderate relationship between PODS-CS and depression. Sullivan et al. [56] further demonstrated that individuals with moderate and high PODS-CS scores were more likely to have had a previous drug use disorder diagnosis than those with low PODS-CS scores. However, no data were available on instrument reliability, longitudinal construct validity, ability to detect change, nor clinically important within-person change.

Hansen’s aberrant behaviors list

Based on a review of the literature and a survey of clinicians, Hansen and colleagues developed a self-report instrument of inappropriate medication use that asks respondents about the occurrence of 20 “aberrant” behaviors over the past 90 days (Appendix D; [26]). This instrument was used to estimate the rate of abuse in HIV-infected individuals who used analgesics. Creation of this instrument involved a review of the literature, as well as a survey of experts [26], although input from patients was not reported. Review of the 20 items supports content validity for measuring inappropriate medication use events, although the time frame does not necessarily reflect “current” inappropriate use, nor are the details necessary for classifying events collected (e.g., intention underlying use, administration route). Additional measurement properties were not evaluated.

Jeevanjee’s opioid analgesic misuse checklist

Jeevanjee and colleagues [28] created an 8-item self-report checklist of opioid analgesic misuse for use with homeless HIV-positive individuals prescribed antiretroviral medication (Appendix E). A positive answer to 1 or more of the 8 items in the past 90 days was categorized as opioid misuse. No information was provided regarding item development. The items do appear content valid for this context of use, despite the 90-day time frame which may not suggest current inappropriate use, and a lack of questions to capture information needed to classify inappropriate use events. This instrument was used to explore the relationship between opioid misuse and adherence to antiretroviral medications, demonstrating that adherence was significantly lower among opioid misusers. No additional measurement properties were provided for this instrument.

Clinician-reported instruments: non-specific

Addiction Severity Index, Fifth Edition (ASI 5th Ed)

The ASI, an interview developed by McLellan and colleagues [40], assesses the functional status of a person with substance abuse, and addresses multiple areas of a substance abuser’s life (i.e., medical, employment/support, alcohol, drug, legal, family/social, psychiatric). A high score in each area of the ASI indicates a greater need for treatment [39]. The 5th edition was published in 1992 [38], with a short form published in 2007 that eliminated items typically not asked (i.e., family history, interviewer’s rating of substance abuse severity; [10]). One section of the ASI assesses the frequency of use of 12 drug classes, including “other opiates/analgesics,” over the past 30 days (Appendix F). Details regarding development of the ASI are not reported in the original manuscript [40], although a later manuscript describes a review of the literature in the ASI’s creation [39]. Further, the 5th edition revisions were pilot tested with 42 patients to ensure that the items and instructions were understood correctly [38]. For the specific context of use identified here, a substantial challenge regarding use of the ASI is that it fails to distinguish therapeutic use of prescription medications as instructed by a clinician from inappropriate use, which may lead to artificially inflated estimates of inappropriate medication use. Additionally, although some items address the medication or substance that causes the most substantial problems, the majority of items do not separate the types of substances used inappropriately. Although this contextual information may be useful when identifying events and classifying them into inappropriate use categories, a focus on inappropriate use of many substances without any differentiation makes it impossible to assess a specific medication’s abuse potential. Not all items are applicable to current inappropriate use, as well, with some assessing lifetime substance abuse treatment, and none focusing on details necessary for classifying events (e.g., intention, route of administration). Evaluations of the 5th edition of the ASI showed that the internal consistency, inter-rater reliability, test-retest reliability, and criterion validity of the drug use composite score were low (Table 1; [10,33]), with no additional data on content validity, longitudinal construct validity, ability to detect change, nor clinically important within-person change.

Clinician-reported instruments: prescription drug specific

Abuse Index Algorithm (AIA)

The AIA was developed as a telephone interview for a clinical trial that compared the abuse potential of tramadol to hydrocodone and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; [1]). Four dimensions are assessed in the AIA: (1) inappropriate use, (2) use for purposes other than intended, (3) inability to stop its use, and (4) withdrawal (only included in the score if the patient has discontinued treatment; Appendix G). Information on the development of the AIA supports content validity as a general measure of inappropriate medication use in clinical trial patients. Creation of this instrument involved literature review, use of the American Academy of Pain Management (AAPM), American Pain Society (APS), and American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM; [2]) consensus statement on behavioral indicators of addiction, DSM-IV-TR abuse and dependence classifications, and input from the study steering committee. Items were pilot tested with 30 patients to ensure they were understood and did not duplicate one another. Although the AIA has promise as a measure to evaluate inappropriate medication use in clinical trials, no time frame is specified for the items, nor do all items necessarily reflect current inappropriate use (e.g., “Did not try to stop but said it would be hard”). No items assess information needed to classify inappropriate use events, as well, indicating that this instrument has limited content validity for the specific context of use identified for this review.

In the original trial, patients with pain who received hydrocodone had significantly more positive AIA scores (i.e., 2 out of 3 points if patient has not discontinued treatment vs. 3 out of 4 points if patient has discontinued treatment) than patients in the tramadol or NSAID groups. Further, data characterizing the AIA are limited to the initial development manuscript (Adams 2006), and no data were identified regarding reliability, longitudinal construct validity, ability to detect change in inappropriate medication use, nor clinically important within-person change.

Clinician-reported instruments: opioid specific

Prescription Opioid Abuse Checklist (POAC)

The POAC is a 5-item “clinical checklist” developed by pain treatment specialists (Appendix H; [13]). Items in the POAC were designed to assess opiate abuse, as defined by the DSM-III-R and the World Health Organization guidelines, to better inform clinicians about patients with chronic pain who may need additional opioid supervision or who may be at risk for inappropriate opioid use. Development of the POAC involved input from six Veterans Affairs physicians, pain fellows, and psychologists who worked closely with patients with pain. No information was reported on literature reviews or patient involvement in creating the POAC. Overall, the items do appear to be content valid as a measure of general inappropriate medication use, although there is some ambiguity about whether multiple calls to a medical office regarding problems with an opioid equates to inappropriate medication use in all circumstances (item 3; Appendix H), as well as the absence of items to capture information needed to identify distinct categories of inappropriate use events. Further, the lack of a time frame is problematic in identifying current inappropriate use. Although this instrument has shown a high inter-rater reliability when evaluated in patients with pain on chronic opioid therapy (Table 1 [13]), to our knowledge no further measurement properties have been published evaluating the POAC’s content validity, cross-sectional and longitudinal construct validity, ability to detect change, or clinically important within-person change.

Prescription Drug Use Questionnaire (PDUQ)

Developed in 1998 by Compton and colleagues, the PDUQ is a 42-item interview for patients with pain on chronic opioid therapy; it is administered by a trained clinician to screen for “addictive disease” [17]. The PDUQ assesses the patient’s pain condition and pain management, past and current problems with pain medication, family history of chronic pain and substance use disorders, and psychiatric history (Appendix I). The PDUQ was developed by considering ASAM and DSM-IV criteria for addiction, as well as a literature review and a review of the records of pain patients with addiction. No information was reported regarding input from experts or patients. With respect to content validity for evaluating inappropriate medication use in clinical trials, much of the content of the PDUQ is unrelated to the concept of interest. For example, patients are asked to report on the number of painful conditions, whether they receive disability payments, any family history of addiction, or anger or mistrust toward previous health care providers (Appendix I). Although such contextual information may help to identify and classify inappropriate use events, these are not events themselves. Most PDUQ items do not specify a time frame and the one that does asks about a patient’s behavior over the past 6 months, rather than current behavior. The PDUQ does not contain items to assess information that is pertinent to classifying inappropriate use events, as well.

The internal consistency of the PDUQ has ranged from high in a sample of patients with pain referred to a pain clinic for inappropriate medication use [17] to poor in a heterogeneous sample of patients on chronic opioid therapy (Table 1; [3]). Compton et al. [17] reported significantly higher PDUQ scores among individuals with substance use disorders than those without. Two alternate versions of the PDUQ have been developed: (1) a self-report version (PDUQp; [18]) and (2) a shortened 15-item interview version [3]. The PDUQp has demonstrated moderately strong psychometric properties in patients from a pain clinic (Table 1; [18]) and factor loadings of the 15-item version distinguished the PDUQ items from items assessing substance abuse disorders [3]. Although the 3 versions of the PDUQ have shown some promising measurement properties, there are insufficient data documenting content validity, reliability, construct validity, ability to detect change, and clinically important within-person change.

Manchikanti’s screening evaluation tool

Manchikanti and colleagues developed a screening tool to determine whether patients in pain treatment centers are inappropriately using controlled substances [35]. Items were developed using a review of the literature; expert and patient input was not reported. Consideration of the items does suggest content validity for this context of use, although the lack of time frame is problematic in identifying current inappropriate use. Additionally, it appears that no items assess information needed to classify inappropriate use events (e.g., intention, route of administration). In the initial version, a physician interviews the patient and provides ratings on 3 domains: (1) excessive opioid needs, (2) use of deception or lying to obtain controlled substances, and (3) current or prior intentional doctor shopping [35]. These 3 domains distinguished between patients with and without a history of drug abuse (Table 1; [35]). In a 2004 study, an additional domain was added: (4) the presence of current or prior use of illicit drugs and denial [34], with the 4 domain tool continuing to distinguish between patients with controlled substance abuse and patients without controlled substance abuse. Although these results are promising, additional data on the tool’s measurement properties (i.e., content validity, reliability, construct validity, ability to detect change in inappropriate medication use, and clinically important within-person change) would be necessary before implementation in analgesic clinical trials.

Prescription Opioid Therapy Questionnaire (POTQ)

Adapted from the POAC [13], the POTQ is a 6-item questionnaire that evaluates aberrant medication behaviors in patients with chronic pain (Appendix J; [42]). Additional information was not provided regarding POTQ development. Item review suggests they are content valid for this context of use, with the exception that no time frame is specified in identifying inappropriate use and items do not capture information necessary to categorizing inappropriate use events. Clinicians complete the POTQ, although it is not clear whether they do so by means of an interview or based on their observations. When possible, clinician responses are verified by chart review. Patients with pain on chronic opioid therapy who reported legal problems, drug or alcohol abuse, or a family history of substance abuse scored significantly higher on the POTQ than did individuals without these characteristics (Table 1; [42]). Wasan et al. [62] demonstrated that patients reporting opioid craving had significantly higher POTQ scores than those without craving. However, no additional data are available to evaluate the content validity, reliability, construct validity, ability to detect change, or clinically important within-person change.

Pain Assessment and Documentation Tool (PADT)

The PADT, a tool to assess and document outcomes in patients with pain undergoing opioid therapy, contains a section asking clinicians to report their observations of a patient’s “aberrant” opioid use behaviors, social and emotional changes, and appearance based on interaction and discussion with the patient [48]. Item generation involved a literature review, input from a panel of pain and addiction management experts, and feedback from clinicians who had pilot tested the PADT, with no information provided about patient input. The PADT was developed to help clinicians document patient status during visits and is not intended to be used as a research tool. It has limited content validity for the given context of use due to a lack of specified time frame. Items that evaluate contextual factors such as mood, abuse history, and involvement in car accidents are also included, which may help to identify and classify inappropriate medication use events, although they do not necessarily indicate current inappropriate use events themselves. Additionally, no psychometric data were identified for this measure.

Addiction Behaviors Checklist (ABC)

Wu et al. developed the 20-item ABC as an instrument to identify current behaviors suggestive of addiction in a patient taking opioid analgesics (Appendix K; [63]). A clinician completes the ABC based on patient interview, observations, interview of relatives, and review of the prescription monitoring report and the medical chart. Creation of the ABC involved a literature review; items were selected to be consistent with the consensus definition of addiction developed by AAPM, APS, and ASAM [2,63]. No description of expert or patient input was provided. Inspection of the ABC items suggests that not all are content valid for evaluating the concept of interest of inappropriate medication use in clinical trials (e.g., items measuring the presence of problematic alcohol use, problems with family, need for analgesic medications), although these factors may help to identify and classify events into inappropriate use event categories. Additionally, no items were reported that capture pertinent information needed to distinguish between inappropriate use event categories (e.g., intention, route of administration).

The inter-rater reliability for veterans on chronic opioid therapy who attended a Veterans Administration pain clinic was high (Table 1; [63]). In addition, the ABC was moderately correlated with the PDUQ, patients who were identified by their clinicians as using medications inappropriately scored significantly higher on the ABC than patients who were not identified as inappropriate users, and a cutoff score of ≥ 3 was associated with good sensitivity and specificity using clinician-identified inappropriate medication use as the criterion [63]. Subjects who dropped out of this study due to inappropriate medication use showed a significantly greater ABC scores at the last visit before discontinuation compared to ABC scores for completers or study withdrawals not due to inappropriate medication use. The ABC is designed to track patients at every visit and has good psychometric properties in the initial development data, but additional testing of the ABC is needed to further explore its measurement properties.

Prescription Opioid Misuse Index (POMI)

The POMI is a 6 item interview that was developed to examine correlates of inappropriate oxycodone use [31]. Respondents are asked about behaviors that may reflect inappropriate medication use (Appendix L). No information was reported about the development of the POMI. The items appear content valid for this context of use, although no time frame is specified for identifying inappropriate use and the items do not identify information necessary to categorize inappropriate use events. When evaluated in chronic pain patients prescribed oxycodone and individuals with an oxycodone substance abuse disorder, a POMI cutoff score of ≥ 2 out of 6 demonstrated good sensitivity and specificity using the DSM-IV criteria for opiate abuse or dependence (Table 1; [31]). Although this instrument shows promise for the assessment of inappropriate medication use behaviors, the data characterizing the POMI came solely from the initial development study, with only limited assessment of concurrent construct validity and no assessment of content validity, reliability, construct validity, ability to detect change, or clinically important within-person change.

Composite Instruments

Aberrant Drug Behavior Index (ADBI) and the Drug Misuse Index (DMI)

Within the last decade, composite instruments have emerged that uniquely assess inappropriate medication use with a combination of patient- and clinician-reported instruments, as well as urine drug testing. Butler and colleagues developed the ADBI, which categorizes patients as inappropriately using their medications if: (1) they score highly on the PDUQ (section 3.6.2); (2) at least 2 out of 3 staff members indicate a serious problem with medications, or (3) there is urine drug test evidence of a non-prescribed medication or illegal substance or the absence of the patient’s prescribed medication [8]. Although this version of the ADBI was used as a “gold standard” to validate the Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain (SOAPP, a measure of risk for inappropriate medication use; [8]), details of instrument development and measurement properties for the ADBI were not provided. A slightly modified version of the original ADBI, created by Wasan and colleagues [62], required a high PDUQ score or a high POTQ score in conjunction with a positive urine drug test in order to classify a patient as an inappropriate medication user. No information was reported regarding the development of the modified ADBI. Individuals who scored highly on this version of the ADBI had a significantly higher craving score than low ADBI scorers (Table 1; [62]), supporting construct validity. Both the original and modified versions of the ADBI have limited content validity for the specific context of use due to the use of the PDUQ, which itself includes items that limit content validity for assessing inappropriate medication use events in clinical trials (see section 3.6. 2). Additionally, the components of the ADBI also do not focus on information necessary for classifying distinct inappropriate use events.

Another composite instrument, the DMI, is also used to identify inappropriate medication use by means of high COMM and SOAPP scores, or a high POTQ score and a positive urine drug test (absence of prescribed opioids in urine test did not constitute a positive score; [61]); however, no information on instrument development or psychometric data were identified for the original DMI. A second version of the DMI was described by Jamison and colleagues [27]; it involved a high PDUQ score or a high ABC score along with a positive urine drug screen (absence of prescribed opioids results in a positive score). Details of the development of the revised DMI were not reported. Individuals who were at high risk for inappropriate opioid use who received no opioid monitoring and counseling scored highly on the DMI, whereas lower scores were seen among low-risk patients and high-risk patients who underwent counseling [27], providing support for construct validity. As with the ADBI, the original and modified versions of the DMI have limited content validity for the specified context of use given the inclusion of the COMM, PDUQ, and ABC instruments, the limitations of which have previously been discussed (see sections 3.3.1, 3.6.2, 3.6.6). Further, the DMI does not include items to assess information needed when categorizing inappropriate use events.

These composite instruments are an appealing approach to triangulate an individual’s inappropriate medication use. However, few data are available on their measurement properties (i.e., little information on construct validity; no information on content validity, reliability, ability detect to change in inappropriate use, and clinically important within-person change), in addition to a lack of content validity to assess current inappropriate medication use in clinical trials. It is also important to note that, as designed, these composite instruments may have low specificity in identifying the abuse potential of a single specific medication because the urine drug tests were classified as positive when any illicit substances or non-prescribed medications were present.

Discussion

This systematic review summarizes patient-reported, clinician-reported, and composite instruments assessing inappropriate medication use, with a specific focus on whether each instrument is suitable for evaluating abuse potential (i.e., the occurrence of abuse events) in clinical trials. To that end, we examined whether each instrument’s published data met rigorous measurement and psychometric criteria, such as those used in current regulatory qualification standards for drug development [21,22,58,60]. Not all instruments were developed for the specific concept of interest and context of use addressed herein; several were developed for other purposes, but are considered here as they had the potential to be applicable to the assessment of inappropriate medication use in clinical trials. Variability in the reasons underlying development of these scales may partially explain a universal limitation: that is, all of these instruments require additional evaluation to better gauge their validity, reliability, and ability to detect change within the context of an RCT. In the properties reviewed for each instrument, the distinct components of content validity, reliability (i.e., internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and inter-rater reliability), as well as construct validity (cross-sectional and longitudinal), ability to detect change, and clinically important within-person change were infrequently evaluated. The development methods were not described for some instruments and many did not report patient or expert input or a literature review as part of instrument development, failing to support content validity. Further, the reviewed instruments generally were limited in content validity for evaluating the specific concept of interest (i.e., current inappropriate medication use events) in the context of use that was our focus (i.e., clinical trials).

An additional limitation of the selected instruments is that many are described as assessments of medication misuse, abuse, or aberrant use, terms that have not been used consistently in the literature [54]. A lack of standardized terminology creates ambiguity regarding the exact type of inappropriate medication use that each instrument assesses. It is also important to understand the intent underlying the inappropriate use. In general, the instruments attempt to identify general inappropriate use without distinguishing between types of inappropriate use (e.g., was the intent of the inappropriate use therapeutic [misuse-event indicator], or was it nontherapeutic for the purpose of achieving a psychological or physiological effect [abuse-event indicator]; [54]), despite the importance of such distinctions in understanding a medication’s abuse potential.

Regarding other psychometric properties, in some cases data were provided on cross-sectional correlations with other measures, as well as the sensitivity and specificity relative to another measure or clinical diagnosis. However, these comparators were often designed to predict or diagnose drug use disorders. Such analyses help establish an instrument’s appropriateness as an assessment of disease states within a patient, but do not demonstrate the instrument’s validity as a measure of the abuse potential of a medication within the context of a clinical trial. Although psychiatric diagnostic criteria serve as a gold standard for identifying drug use disorders, currently no gold standard exists for identifying current inappropriate medication use. Additional empirical work is required to develop an instrument that can serve as the gold standard for evaluating distinct categories of inappropriate use. Relatedly, the reviewed instruments often did not specify whether current or lifetime inappropriate use was being assessed, nor did they evaluate inappropriate use of a target drug. This suggests that their focus may be to identify drug use disorders or the risk of drug use disorders within patients, and as such, these instruments are not appropriate for evaluating a specific medication’s abuse potential. In addition, given the diversity among these instruments in number of items and their content, it is important to evaluate patient and clinician burden associated with their use when choosing among them; however, such considerations are beyond the scope of our review.

The results of this review are similar to prior reviews of inappropriate medication use instruments [5,14,46,47], in that the instruments are generally concluded to be imperfect. However, earlier reviews often come to this conclusion by focusing on the quality and quantity of data on measurement properties, which suggests that more and better quality data could indicate an instrument’s utility. What differs in this review is that the individual items were evaluated for their content validity regarding the concept of interest (i.e., current inappropriate medication use) within the context of clinical trials use. Given that the majority of the instruments contain items that are not applicable to assessing this concept and context, in most cases our conclusion that these instruments are not appropriate cannot be altered by additional data collection on the instruments’ other measurement properties (e.g., construct validity, reliability, ability to detect change). Although the reviewed instruments have limitations, we recognize that investigators will need to choose an instrument to assess inappropriate medication use. We hope that the material presented in this review will assist investigators in selecting an instrument that most closely matches their selected context of use (e.g., type of treatment, pain condition, participants) until better instruments are developed.

One limitation of this systematic review is that we evaluated the validity of the instruments to assess the concept of interest (i.e., current inappropriate medication use) based on the available empirical evidence regarding inappropriate use. For example, as described in section 3.2.1 on the DAST, the presence of withdrawal symptoms is not necessarily indicative of inappropriate use. However, future research may demonstrate that individuals who misuse their medication (e.g., take the medication as needed, rather than according to prescribed dosing instructions) exhibit withdrawal symptoms because they run out of medication before they can refill the prescription. Although this scenario seems plausible, we felt it prudent to conclude that such items do not measure the concept of interest until evidence exists supporting their ability to identify categories of current inappropriate medication use. A second limitation is that we were only able to review the information regarding measurement properties that was reported in the published manuscripts. It is possible that additional efforts were made to evaluate each instrument’s content and construct validity, reliability, ability to detect change, and clinically important within-person change without authors reporting these details. However, such efforts cannot be evaluated when they are not explicitly reported. We recommend that authors fully describe the process of development in the initial instrument manuscript, as well as reporting all relevant information regarding instrument measurement properties. Finally, this review evaluates instruments for a specific context of use and concept of interest using regulatory recommendations. It is likely that a review of these instruments for different concepts, contexts, and using different standards would come to a different conclusion about their utility.

Conclusion

The instruments currently available to assess inappropriate medication use may help clinicians evaluate their patients’ risks for inappropriate use or drug use disorders. However, these instruments currently have unknown applicability to the context of clinical trials and to evaluating a medication’s abuse potential, as well as limited information available with which to evaluate their validity, reliability, and ability to detect change. Accurately assessing inappropriate medication use in RCTs is vitally important to understanding a medication’s risk profile, and thus efforts should be devoted to the development and qualification of valid, reliable, and sensitive instruments for use in this context. Such an instrument should apply standardized classifications and definitions of inappropriate use events [54], and crucially, attention must be paid to understanding the intent behind inappropriate use events. This will distinguish abuse and non-abuse events, in turn generating more accurate characterizations of abuse potential.

Supplementary Material

Instruments of misuse, abuse, addiction, and/or craving of prescription drugs

Perspective.

This systematic review evaluates the measurement properties of inappropriate medication use (e.g., abuse, misuse) instruments to determine whether any meet regulatory standards for clinical trial outcome measures to assess abuse potential.

Research highlights.

Evaluated inappropriate medication use instruments according to regulatory standards.

Most instruments lacked content validity for assessing inappropriate use events in clinical trials.

Data on other measurement properties (e.g., construct validity, detecting change) were limited.

A psychometrically sound instrument for inappropriate use events in clinical trials is needed.

Acknowledgments

This article was reviewed and approved by the Executive Committee of the ACTTION public-private partnership. We thank Sharon Hertz, MD, and Allison H. Lin, PharmD, PhD, from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for their numerous contributions to ACTTION. We also thank Jennifer S. Gewandter from the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry for her valuable feedback on this manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and no official endorsement by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or the pharmaceutical companies that provided unrestricted grants to support the activities of the Analgesic, Anesthetic, and Addiction Clinical Trial Translations, Innovations, Opportunities, and Networks (ACTTION) public-private partnership should be inferred. Financial support for this project was provided by the ACTTION public-private partnership, which has received research contracts, grants, or other revenue from the FDA, multiple pharmaceutical and device companies, and other sources.

References

- 1.Adams EH, Breiner S, Cicero TJ, Geller A, Inciardi JA, Schnoll SH, Senay EC, Woody GE. A comparison of the abuse liability of tramadol, NSAIDs, and hydrocodone in patients with chronic pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31:465–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Academy of Pain Medicine, American Pain Society, American Society of Addiction Medicine. Definitions related to the use of opioids for the treatment of pain. WMJ. 2001;100:28–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banta-Green CJ, Merrill JO, Doyle SR, Boudreau DM, Calsyn DA. Measurement of opioid problems among chronic pain patients in a general medical population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;104:43–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banta-Green CJ, Von Korff M, Sullivan MD, Merrill JO, Doyle SR, Saunders K. The prescribed opioids difficulties scale: a patient-centered assessment of problems and concerns. Clin J Pain. 2010;26:489–97. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181e103d9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becker WC, Fraenkel L, Edelman EJ, Holt SR, Glover J, Kerns RD, Fiellin DA. Instruments to assess patient-reported safety, efficacy or misuse of current opioid therapy for chronic pain: a systematic review. Pain. 2013;154:905–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butler SF, Budman SH, Fanciullo GJ, Jamison RN. Cross validation of the current opioid misuse measure to monitor chronic pain patients on opioid therapy. Clin J Pain. 2010;26:770–6. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181f195ba. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butler SF, Budman SH, Fernandez KC, Houle B, Benoit C, Katz N, Jamison RN. Development and validation of the Current Opioid Misuse Measure. Pain. 2007;130:144–56. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butler SF, Budman SH, Fernandez K, Jamison RN. Validation of a screener and opioid assessment measure for patients with chronic pain. Pain. 2004;112:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butler SF, Budman SH, Goldman RJ, Newman FL, Beckley KE, Trottier D, Cacciola JS. Initial validation of a computer-administered Addiction Severity Index: the ASI-MV. Psychol Addict Behav. 2001;15:4–12. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.15.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cacciola JS, Alterman AI, McLellan AT, Lin YT, Lynch KG. Initial evidence for the reliability and validity of a “Lite” version of the Addiction Severity Index. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87:297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carey KB, Carey MP, Chandra PS. Psychometric evaluation of the alcohol use disorders identification test and short drug abuse screening test with psychiatric patients in India. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:767–74. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cassidy CM, Schmitz N, Malla A. Validation of the alcohol use disorders identification test and the drug abuse screening test in first episode psychosis. Can J Psychiatry. 2008;53:26–33. doi: 10.1177/070674370805300105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chabal C, Erjavec MK, Jacobson L, Mariano A, Chaney E. Prescription opiate abuse in chronic pain patients: clinical criteria, incidence, and predictors. Clin J Pain. 1997;13:150–5. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199706000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, Miaskowski C, Passik SD, Portenoy RK. Opioids for chronic noncancer pain: prediction and identification of aberrant drug-related behaviors: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society and American Academy of Pain Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Pain. 2009;10:131–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cocco KM, Carey KB. Psychometric properties of the Drug Abuse Screening Test in psychiatric outpatients. Psychol Assess. 1998;10:408–14. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Comer SD, Zacny JP, Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Bigelow GE, Foltin RW, Jasinski DR, Sellers EM, Adams EH, Balster R, Burke LB, Cerny I, Colucci RD, Cone E, Cowan P, Farrar JT, Haddox JD, Haythornthwaite JA, Hertz S, Jay GW, Johanson CE, Junor R, Katz NP, Klein M, Kopecky EA, Leiderman DB, McDermott MP, O’Brien C, O’Connor AB, Palmer PP, Raja SN, Rappaport BA, Rauschkolb C, Rowbotham MC, Sampaio C, Setnik B, Sokolowska M, Stauffer JW, Walsh SL. Core outcome measures for opioid abuse liability laboratory assessment studies in humans: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2012;153:2315–24. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Compton P, Darakjian J, Miotto K. Screening for addiction in patients with chronic pain and “problematic” substance use: evaluation of a pilot assessment tool. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1998;16:355–63. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(98)00110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Compton PA, Wu SM, Schieffer B, Pham Q, Naliboff BD. Introduction of a self-report version of the Prescription Drug Use Questionnaire and relationship to medication agreement noncompliance. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36:383–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunbar SA, Katz NK. Chronic opioid therapy for nonmalignant pain in patients with a history of substance abuse: report of 20 cases. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1996;11:163–71. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(95)00165-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]