Abstract

Imatinib, which is an inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase, has been a remarkable success for the treatment of Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+) chronic myelogenous leukemias (CMLs). However, a significant proportion of patients chronically treated with imatinib develop resistance because of the acquisition of mutations in the kinase domain of BCR-ABL. Mutations occur at residues directly implicated in imatinib binding or, more commonly, at residues important for the ability of the kinase to adopt the specific closed (inactive) conformation to which imatinib binds. In our quest to develop new BCR-ABL inhibitors, we chose to target regions outside the ATP-binding site of this enzyme because these compounds offer the potential to be unaffected by mutations that make CML cells resistant to imatinib. Here we describe the activity of one compound, ON012380, that can specifically inhibit BCR-ABL and induce cell death of Ph+ CML cells at a concentration of <10 nM. Kinetic studies demonstrate that this compound is not ATP-competitive but is substrate-competitive and works synergistically with imatinib in wild-type BCR-ABL inhibition. More importantly, ON012380 was found to induce apoptosis of all of the known imatinib-resistant mutants at concentrations of <10 nM concentration in vitro and cause regression of leukemias induced by i.v. injection of 32Dcl3 cells expressing the imatinib-resistant BCR-ABL isoform T315I. Daily i.v. dosing for up to 3 weeks with a >100 mg/kg concentration of this agent is well tolerated in rodents, without any hematotoxicity.

Keywords: ON012380, substrate-competitive, Gleevec

The Philadelphia chromosome (Ph), which was discovered in 1960 by Nowell and Hungerford (1), results from a reciprocal translocation between chromosome 9 at band q34 and chromosome 22 at band q11 (2, 3). This translocation fuses the breakpoint cluster region (Bcr) and the Abl genes and creates the BCR-ABL oncogene (4). Because the BCR-ABL protein is active in >90% of CML cases, it has been possible to synthesize small molecules that inhibit BCR-ABL kinase activity in leukemic cells without adversely affecting the normal cell population. Imatinib (also called Gleevec or STI571) is a small-molecule inhibitor that binds to the kinase domain of BCR-ABL and stabilizes the protein in its closed, inactive conformation (5), thereby inhibiting its activity, and is now a first-line therapy for the majority of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) cases because of its high efficacy level and relatively mild side effects (6). Despite the fact that the majority of patients receiving imatinib respond to treatment at both the hematological and cytogenetic levels, relapse occurs in a large percentage of patients (reviewed in ref. 7). Although several studies have attempted to address the mechanism(s) by which CML cells acquire imatinib resistance (8–10), most studies indicate that mutation of the BCR-ABL gene itself accounts for the majority of imatinib-resistant leukemias in vivo. Mutation within the kinase domain is the most common phenomenon, and, to date, 17 different clinically relevant point mutations within this domain have been identified. It is believed that certain amino acid substitutions interfere with the ability of imatinib to interact directly with the BCR-ABL kinase domain, whereas others destroy or hinder the ability of the BCR-ABL kinase domain to adopt a conformation that is required for imatinib binding (reviewed in refs. 7 and 11).

Because of the frequency of mutations within the kinase domain, efforts are now focused on the identification of novel inhibitors that are active against imatinib-resistant mutants of BCR-ABL. Different approaches have recently been described to overcome this resistance in at least some CML cases. Farnesyltransferase inhibitors, such as SCH66336, and the proteasome inhibitor Bortezomib have been shown to have growth inhibitory effects on certain imatinib-resistant leukemias (12). Other compounds, such as PD180970 and CGP76030, both of which inhibit BCR-ABL by binding to the ATP-binding site, have been shown to induce apoptosis in a few select cases of imatinib-resistant CMLs (13–16). More recently, a broad-spectrum ATP-competitive Src kinase inhibitor, BMS-354825, was shown to inhibit the kinase activity of BCR-ABL (17). Although this compound was able to override imatinib resistance caused by the majority of documented mutations within the BCR-ABL kinase domain, it was ineffective against one of the most common mutations observed in imatinib-resistant patients, T315I. This particular amino acid substitution, thus far, has been resistant to all kinase inhibitors that are ATP mimetics, suggesting that other types of therapeutic strategies are required to overcome resistance caused by this mutation. In this report, we describe the profile of ON012380, a small-molecule inhibitor of BCR-ABL that is active against 100% of imatinib-resistant forms of BCR-ABL, including T315I. Because this compound does not compete with ATP to inhibit BCR-ABL but competes with its substrates, these data suggest that molecules that target sites outside the ATP-binding domain can function as effective therapeutic agents against imatinib-resistant leukemias.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines. 32Dcl3 cells (18) were maintained in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 1 unit/ml penicillin–streptomycin, and 10% WEHI-3B conditioned medium as a source of IL-3 (19). K562 cells were maintained in RPMI medium 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and 1 unit/ml penicillin–streptomycin.

Generation of Wild-Type and Imatinib-Resistant Mutants of BCR-ABL. Oligonucletodies corresponding to published mutations (reviewed in ref. 7) that confer imatinib resistance were used to introduce these mutations into the full-length BCR-ABL cDNA by using PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis (20). All constructs were verified by sequence analysis. pCDNA3-based expression plasmids encoding wild-type and imatinib-resistant forms of BCR-ABL were introduced into actively proliferating 32Dcl3 cells by electroporation as described in ref. 21 and cells selected in the absence of IL-3. The expression of the BCR-ABL proteins was determined by Western blot and kinase assays.

In Vivo Kinase Assays. Cells were treated as indicated, washed with PBS, and lysed in lysis buffer [25 mM Hepes, pH 7.5/0.1% Triton X-100/300 mM NaCl/0.5 mM DTT/0.2 mM EDTA/1.5 mM MgCl2/20 mM β-glycerophosphate/0.2mMNa3VO4/1× protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Diagnostics)]. After high speed centrifugation, 100 μg of clarified total cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation by using 5 μg of an antibody directed against BCR-ABL (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and protein A agarose for 2 h at 4°C. The immunoprecipitates were washed three times in lysis buffer and once in kinase buffer (50 mM Hepes/10 mM MgCl2/1 mM EDTA/2 mM DTT/0.01% Nonidet P-40, pH 7.5), and the kinase reactions were performed in kinase buffer at 30°C for 20 min in a volume of 20 μl containing 100 mM ATP and 40 μCi (1 Ci = 37 GBq) [γ-32P]ATP. The reactions were terminated by the addition of 2× Laemmli buffer and by boiling for 5 min (22). Phosphorylated proteins were resolved by SDS/PAGE, and the resulting gel was subjected to autoradiography.

Western Blot Analysis. Whole-cell extracts were prepared as described above and separated by SDS/PAGE. The resolved proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and probed with antibodies directed against phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (phospho-STAT-5) and STAT-5 (Upstate Cell Signaling Solutions, Lake Placid, NY). Proteins were visualized by using Renaissance Chemiluminescence Reagent (Perkin–Elmer).

In Vitro Kinase Assays with Recombinant Proteins. The wild-type BCR-ABL cDNA was subcloned into the pAcGHLT expression vector, and the recombinant protein was expressed in Sf9 cells and purified as described by the manufacturer (BD Biosciences). Recombinant ABL-T315I protein was purchased from Upstate Cell Signaling Solutions. One unit of recombinant protein was incubated with various concentrations of imatinib, ON012380, or DMSO and reaction buffer (50 mM Hepes, pH 7.5/10 mM MgCl2/1 mM EDTA/2 mM DTT/0.01% Nonidet P-40) in a total volume of 15 μl. After a 30-min incubation at room temperature, 2 μl of 1 mM ATP, 2 μl of [γ-32P]ATP (40 μCi), and 1 μl (1 μg) of Crk were added, and the kinase reactions were performed at 30°C for 20 min. The reactions were terminated by the addition of 20 μl of 2× Laemmli buffer (22) and boiled, and the phosphorylated substrates were resolved by SDS/PAGE. The resulting gels were dried and subjected to autoradiography.

For filter binding studies, kinase assays were performed as described above except that, after the kinase reaction, 10-μl aliquots of the reaction mixture were spotted onto P81 phosphocellulose paper. The filters were washed three times for 5 min each with 0.75% phosphoric acid and once with acetone, and the level of radioactivity was determined by using a liquid scintillation counter. Nonspecific binding was determined by conducting the assay in the absence of enzyme and then subtracting the value from each of the experimental values. The level of kinase activity is expressed as a percent of the maximal kinase activity.

In Vivo Experiments and Colony Formation Assays. Female athymic nude mice (ncr/ncr) were injected i.v. with 1 × 106 32Dcl3 cells expressing BCR-ABLT315I in the tail vein. Treatments (10 mice per group) were started 24 h after cell injections by daily i.p. injections of saline (vehicle), ON012380 (100 mg/kg), or imatinib (100 mg/kg). Imatinib injections were terminated after 10 days because of toxicity. Body weights were taken every 2 days, and blood smears were performed 7 and 14 days after the start of treatments. One drop of blood from each mouse was smeared onto glass slides, air dried, and stained with modified Wright stain (Sigma). The number of T315I cells, which were easily visible because of their blue staining and size difference, per every 10 fields was determined by counting 10 fields of view containing an equal density of red blood cells with a 40× objective on an upright Olympus microscope. For bone marrow colony formation assays, bone marrow cells from control and ON012380-treated mice were harvested and plated in methylcellulose medium (MethoCult) supporting the growth of myeloid, erythroid, and lymphoid lineages as described by the manufacturer (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver).

Results

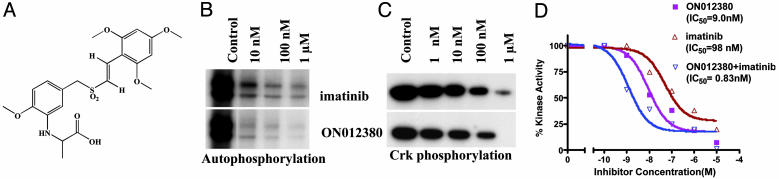

Derivation of a Substrate-Competitive Inhibitor of BCR-ABL. Because it is now apparent that a significant proportion of patients chronically treated with imatinib develop resistance because of an acquisition of mutations in the kinase domain of BCR-ABL, our aim was to generate a highly potent inhibitor of BCR-ABL by targeting its non-ATP binding sites. We have recently described the synthesis of a family of small-molecule kinase inhibitors that are unrelated to ATP (23–25) or other purine and pyrimidine nucleosides and exhibit potent antitumor activity. Screening of this library of molecules for inhibitors of BCR-ABL kinase activity led to the identification of one compound, ON012380 (Fig. 1A) that had potent inhibitory activity. In vitro studies of purified recombinant BCR-ABL preparations showed that ON012380 exhibited strong inhibition of BCR-ABL kinase activity as evidenced by the inhibition of BCR-ABL autophosphorylation as well as Crk phosphorylation, which was used as a substrate (Fig. 1 B and C). Filter binding assays performed with the recombinant protein showed the IC50 of this compound to be 9.0 nM. When these assays were performed by using a purified preparation of imatinib, the IC50 was found to be ≈100 nM, which is in close agreement with published data (26). Thus, ON012380 appears to be ≈10-fold more active than imatinib in BCR-ABL kinase inhibition assays (Fig. 1D). More interestingly, when a mixture of imatinib and ON012380 was used in these assays, these compounds were found to act synergistically to inhibit BCR-ABL, suggesting that they bind to the BCR-ABL kinase at different positions and that this dual binding may lead to potent inactivation of enzymatic activity. (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

BCR-ABL inhibitory activity of ON012380. (A) Structure of ON012380. (B and C) Ten nanograms of recombinant BCR-ABL protein was mixed with different concentrations of the indicated inhibitor, and kinase assays were performed by using Crk as a substrate to measure autophosphorylation and substrate (Crk) phosphorylation. (D) BCR-ABL kinase assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods by using c-Crk as a substrate. The reactions mixtures were spotted onto strips of P81 phosphocellulose paper, washed, and counted. In experiments for which a mixture of imatinib and ON012380 was used, the reaction mixtures contained a constant amount of imatinib (10 nM) and various amounts of ON012380. The values from individual samples were analyzed and plotted as a function of drug concentration. Data points represent an average of three independent experiments performed in duplicate.

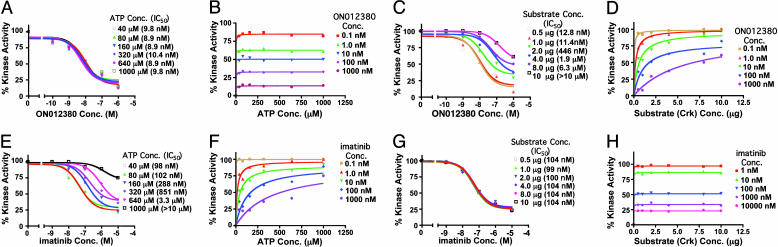

Biochemical Mechanism of Action of ON012380. To define the biochemical mechanism of action of ON012380, we examined the effects of increasing concentrations of ATP or a substrate protein (Crk) on the inhibitory activity of this compound by using steady-state analysis. Ten nanograms of recombinant BCR-ABL was mixed with different concentrations of ON012380, and kinase assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods by using [γ-32P]ATP and various concentrations of ATP. The values from individual samples were analyzed and plotted as a function of drug concentration (Fig. 2A), and values for Km (62 μM) and Vmax (89 μmol/min) for the reaction were obtained by fitting the data to the Michaelis–Menton equation (27) (Fig. 2B). These analyses showed that the velocity of substrate phosphorylation was unaltered in the presence of increasing ATP concentrations and that the Km values remained unchanged, suggesting that ON012380 is not an ATP-competitive inhibitor (Fig. 2 A and B). This is also demonstrated by the IC50 values which remained unchanged in the presence of increasing ATP concentrations. When the same experiments were performed with imatinib, an opposite result was obtained in which ATP effectively competed with the inhibitor as suggested by an increased IC50 with increasing concentration of ATP (Fig. 2 E and F), which is accordance with data published in ref. 28. We next examined the effects of increasing substrate concentrations on the inhibitory activity of the compound in the presence of a constant amount of ATP. Our results (Fig. 2 C and D) showed that increasing the concentration of the substrate resulted in increased IC50 values for the drug. Data analysis with the Michaelis–Menton equation (27) demonstrated that the maximal velocity of BCR-ABL was not significantly affected by the inhibitor despite the fact that the Km values were significantly increased. The increase in Km combined with the unchanged Vmax in the presence of an inhibitor is characteristic of competitive inhibition. The increased IC50 values in the presence of increased substrate concentration for the inhibition of BCR-ABL kinase activity (Fig. 2C) further demonstrate the substrate-dependent and ATP-independent nature of inhibition. When these assays were performed with imatinib, there was no change in the Km values with increasing concentration of the substrate (Fig. 2 G and H), confirming previously published data showing that imatinib acts as an ATP-dependent and substrate-independent inhibitor of BCR-ABL.

Fig. 2.

Steady-state kinetic analysis of BCR-ABL kinase inhibition by ON012380. (A) BCR-ABL kinase inhibition assays were performed as described for Fig. 1 in a reaction mixture containing [γ-32P]ATP and various concentrations (conc.) of ATP. The values from individual samples were analyzed and plotted as a function of inhibitor concentration. The IC50 of ON012380 for kinase activity was calculated. (B) The curves represent calculated best fits to the Michaelis–Menton equation with a constant amount of substrate and various amounts of ATP and ON012380. (C) BCR-ABL kinase inhibition assays with different concentrations of ON012380 and various concentrations of substrate (Crk) were performed, and the values from individual samples were analyzed and plotted as a function of inhibitor concentration. (D) Michaelis–Menton curves for BCR-ABL with a curve fit derived by using nonlinear regression analysis is shown for data obtained by using a constant amount of ATP and various amounts of substrate and ON012380. (E) Inhibition assays with recombinant BCR-ABL protein and different concentrations of imatinib were performed in the presence of various concentrations of ATP as described for A. (F) The curves represent calculated best fits to the Michaelis–Menton equation with a constant amount of substrate and various amounts of ATP and imatinib. (G) Inhibition assays with recombinant BCR-ABL protein and different concentrations of imatinib were performed in the presence of various concentrations of substrate (Crk) as described for E, and the values from individual samples were analyzed and plotted as a function of drug concentration. (H) The curves represent calculated best fits to the Michaelis–Menton equation with a constant amount of ATP and various amounts of substrate and imatinib.

We next examined the inhibitory effects of ON012380 on a panel of serine/threonine and tyrosine kinases (Table 2, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). These studies showed that ON012380 does not exhibit significant inhibitory activity against any of the other kinases tested. However, at higher concentrations, this compound was found to inhibit the platelet-derived growth factor receptor as well as the LynB and Fyn tyrosine kinases. These results suggest a common feature shared between these tyrosine kinases in their substrate binding sites. Of the kinases tested, ON012380 was most active against BCR-ABL, which is likely to be its primary target.

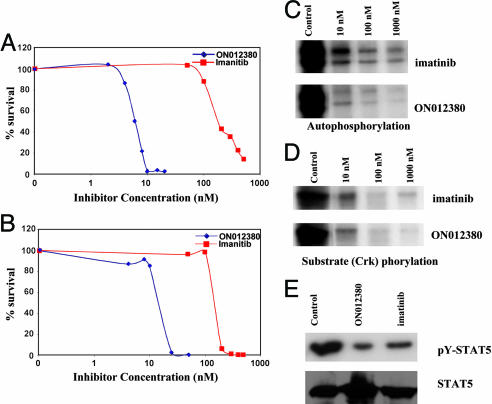

Activity of ON012380 Against BCR-ABL-Expressing Cell Lines. To determine the activity ON012380 against BCR-ABL-expressing cell lines, we incubated K562 cells as well as 32Dcl3 cells that ectopically expressed the wild-type p210BCR-ABL oncoprotein with various concentrations of ON012380 for a period of 72 h and determined their viability by trypan blue exclusion. Incubation of both cell lines with ON012380 (Fig. 3 A and B) resulted in a rapid loss of viability, with a LD50 of 10–15 nM. When these assays were performed by using imatinib, the IC50 of this compound was found to be >100 nM (Fig. 3 A and B), which is in close agreement with published data (26). Thus, ON012380 was capable of inhibiting the proliferation of BCR-ABL+ cell lines at a concentration that is 10-fold less than that of imatinib.

Fig. 3.

In vitro tumor-cell-killing activity of ON012380. (A and B) Effect of ON012380 and imatinib on the viability of Ph+ human CML K562 (A) and murine 32D/BCR-ABL (B) cells. The two cell lines were incubated with increasing concentrations of the indicated compounds, and the total number of viable cells was determined 72 h after treatment by trypan blue exclusion. (C and D) K562 cells were treated with various concentrations of imatinib or ON012380, and the BCR-ABL immunoprecipitates were subjected to in vitro kinase assays. BCR-ABL autophosphorylation (C) and substrate (Crk) phosphorylation (D) are shown. (E) Total cell lysates derived from K562 cells treated with DMSO (control), imatinib, or ON012380 were examined by Western blot analysis for the expression of phosphorylated (Upper) and nonphosphorylated (Lower) forms of STAT-5.

To confirm that the effects that ON012380 had on cell viability correlated with inhibition of BCR-ABL kinase activity, K562 cells were treated with ON012380 for 24 h and the BCR-ABL protein was immunoprecipitated and analyzed for kinase activity. These results (Fig. 3 C and D) showed that this compound readily down-regulated BCR-ABL kinase activity in vivo as judged by autophosphorylation and Crk (substrate) phosphorylation. Because STAT-5 is known to be an important target of the BCR-ABL kinase, we next tested the ability of ON012380 to modulate STAT-5 phosphorylation in vivo in K562 cells. The results of this experiment (Fig. 3E) demonstrate that ON012380 is a potent suppressor of BCR-ABL-mediated STAT-5 phosphorylation. Similar results were obtained with 32D/p210BCR-ABL cells (data not shown).

ON012380 Is a Potent Inhibitor of BCR-ABLT315I Kinase Activity. Because none of the ATP-competitive BCR-ABL inhibitors to date are effective against the imatinib-resistant T315I mutant, it was of interest to determine the effects of ON012380 on the kinase activity of this protein. In vitro inhibition studies of commercially available recombinant ABLT315I protein showed that ON012380 strongly inhibited the kinase activity of this mutant (IC50 of 1.5 nM) (Fig. 4A), whereas imatinib was very ineffective under the same conditions. Thus, ON012380 is at least 10,000-fold more active than imatinib in inhibiting the kinase of activity of the T315I mutant protein in vitro.

Fig. 4.

BCR-ABLT315I inhibitory activity of ON012380. (A) BCR-ABL kinase assays were performed with T315I recombinant protein as described for Fig. 1 by using c-Crk as a substrate. The values from individual samples were analyzed and plotted as a function of inhibitor concentration. (B and C) Imatinib-resistant 32D/BCR-ABLT315I cells were treated with various concentrations of imatinib or ON012380, and the BCR-ABL immunoprecipitates were subjected to in vitro kinase assays. BCR-ABL autophosphorylation (B) and substrate phosphorylation (Crk) (C) are shown. (D) Total cell lysates derived from 32D/BCR-ABLT315I cells treated with DMSO (control), imatinib, or ON012380 were examined by Western blot analysis for the expression of phosphorylated STAT-5.

ON012380 Is Active Against Imatinib-Resistant Tumor Cell Lines. To determine whether ON012380 was active against cells that express imatinib-resistant forms of BCR-ABL, we introduced point mutations into the BCR-ABL cDNA that corresponded to those published in the literature (7) and then introduced them into actively proliferating 32Dcl3 cells (18). Transfectants were selected in the absence of IL-3, and the expression and activity of each mutant was confirmed by Western blot analysis and kinase assays (data not shown). All mutants conferred imatinib resistance at levels comparable to the results of published studies (29) when compared with cells expressing wild-type p210BCR-ABL (data not shown). When these cells were cultured in the presence of increasing concentrations of ON012380, they were all found to be extremely sensitive to the growth inhibitory activity of ON012380, including those expressing the T315I mutant (Fig. 5 and Table 1). The results of four selected cell lines expressing BCR-ABL mutants T315I, E255K, Y253H, and G250E are shown in Fig. 5. Although these cells showed various levels of resistance to imatinib, it was interesting to note that several of these mutants are slightly more sensitive to ON012380 than wild-type BCR-ABL-expressing cells.

Fig. 5.

In vitro tumor-cell-killing activity of cells expressing an inatinib-resistant mutant of BCR-ABL by ON012380. The four representative imatinib-resistant cell lines T315I (A), E255K (B), Y253H (C), and G250E (D) were incubated with increasing concentrations of the indicated compounds, and the total number of viable cells was determined 72 h after treatment by trypan blue exclusion.

Table 1. Sensitivity of imatinib-resistant BCR-ABL mutants to ON012380.

| Mutation | LD50, nM |

|---|---|

| p210wt | 10.0 |

| F317L | 7.8 |

| H396R | 6.8 |

| M351T | 7.8 |

| H396P | 7.9 |

| Y253H | 7.8 |

| M244V | 7.8 |

| E355G | 7.8 |

| F359V | 7.1 |

| G250E | 5.9 |

| Y253F | 6.8 |

| F311L | 6.8 |

| T315I | 7.5 |

| E255V | 7.8 |

| Q252H | 7.0 |

| L387M | 7.1 |

| E255K | 8.4 |

When cell extracts from 32D/BCR-ABLT315I cells incubated in the presence of 1, 10, 100, and 1,000 nM ON012380 or imatinib were subjected to immunoprecipitation followed by kinase assays (Fig. 4 B and C), we observed a dose-dependent reduction in the level of BCR-ABL kinase activity in the ON012380-treated cells, whereas no such reduction was observed in the imatinib-treated samples. When the status of STAT-5 phosphorylation in ON012380 and imatinib-treated cells was examined (Fig. 4D), there was a substantial inhibition of STAT-5 phosphorylation in the ON012380-treated cells, whereas the phospho-STAT-5 levels were unaffected in the imatinib-treated cells. Similar results were obtained by using 32Dcl3 cells that express the other imatinib-resistant mutants listed in Table 1 (data not shown). Taken together, these results suggest that ON012380 effectively inhibits the activity of the imatinib-resistant BCR-ABL proteins, including BCR-ABLT315I.

In Vivo Efficacy of ON012380. To assess the in vivo efficacy of ON012380, athymic nude mice were injected i.v. with 32Dcl3 cells expressing the T315I mutant form of BCR-ABL. For these studies, the mice were injected i.v. through the tail vein with 1 × 106 32Dcl3 cells expressing the T315I mutant; 24 h after injection, the mice were divided into three groups (10 mice per group), with each group receiving either saline (vehicle), ON012380 (100 mg/kg), or imatinib (100 mg/kg) i.p. on a daily basis. The dose and treatment schedule was chosen to mimic the maximum tolerated dose of imatinib (unpublished results) in this particular strain of mice.

On days 7 and 14 after the beginning of treatment, the number of T315I cells in the blood of mice treated with ON012380 was compared with the number of T315I cells found in mice treated with either imatinib or saline. The results of this study (Fig. 6A) showed that the number of T315I cells in the blood of mice treated with ON012380 was significantly reduced on days 7 and 14 as compared with the number of cells found in both the vehicle- and imatinib-treated groups. The ON012380-treated mice showed no signs of toxicity, body weight loss, ruffled coats, lethargy, or abnormal feces. In contrast, administration of imatinib for 10 days produced severe toxicity as judged by a >20% loss of bodyweight, which resulted in the termination of drug administration (Fig. 6B). ON012380 has been shown to be well tolerated over a 21-day period of daily i.p. injections (data not shown) and is therefore well suited for long-term treatments. We have also carried out single dose and repeated dose (28 daily injections) toxicology studies. In mice, a single dose of 300 mg/kg produced no toxicity. During 7 days of repeated dosing, 200 mg/kg per dose was well tolerated. During 28 days of repeated dosing, fixed daily doses of 100 mg/kg were well tolerated. To examine the effects of ON012380 on normal hematopoietic cell population in vivo, we injected an i.v. dose of this compound at a concentration of 200 mg/kg and examined its effect on the in vitro hematopoietic colony formation of normal bone marrow cells derived from these mice 24 h after administration. These studies (Fig. 6C) show that there was no reduction in colony formation of the erythroid, myeloid, or lymphoid lineages. Taken together, this study shows that ON012380 exhibits a very desirable safety profile with a high therapeutic index and can reduce the in vivo growth of imatinib-resistant cells in an efficacious manner.

Fig. 6.

Effect of ON012380 on the in vivo growth of T315I cells. (A) Nude mice (10 mice per group) were injected i.v. through the tail vein with 1 × 106 32D/BCR-ABLT315I cells. Treatment with daily i.p. injections of 100 mg/kg ON012380, 100 mg/kg imatinib, or an equal volume of saline was initiated 24 h later. Blood smears from each mouse were performed on days 7 and 14, and the number of T315I-expressing cells per 10 fields was determined. The data were plotted as the average number of 32D/BCR-ABLT315I cells per 10 fields ± SEM (n = 10). (B) The total body weight of individual mice in the three groups was determined daily, and the average body weights were plotted as the percent of starting body weight. (C) CD-1 mice were injected i.v. (tail vein injection) with saline or ON012380 (200 mg/kg) dissolved in saline. Bone marrow cells were extracted from the mice after 24 h, and 2 × 105 cells were plated on methycellulose containing appropriate cytokines for lineage-specific colony formation. Colonies were counted after 5–14 days of incubation. BFU-E, erythroid burst-forming unit; CFU-G, granulocyte colony-forming unit; CFU-M, macrophage colony-forming unit; CFU-GM, granulocyte/macrophage colony-forming unit; pre-B, pre-B lymphocyte.

Discussion

Recent advances in our understanding of the molecular changes that accompany cell transformation has provided new approaches for the development of cancer therapeutic agents that can potentially target specific oncoproteins that are activated in a cancer cell. Imatinib is one of the first in this new generation of drugs that specifically target the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase (5), and it has been a great success. However, it is becoming clear that a significant portion of patients chronically treated with imatinib develop resistance because of the acquisition of mutations in the kinase domain of BCR-ABL, which are thought to interfere with the ability of the enzyme to adopt the inactive conformation required for imatinib binding. Because selection of highly conserved mutable residues in the ATP binding site appears to be relatively common for many kinases, it has been argued that substrate-competitive inhibitors might constitute better drug candidates (30). Therefore, in our quest to develop other BCR-ABL inhibitors, we chose to develop compounds that do not compete for the ATP binding site of this enzyme, because such compounds offer the potential to be unaffected by mutations that make Ph+ CML cells resistant to imatinib. The results presented in this study describe the identification of such a pharmacophore, ON012380, which targets the BCR-ABL kinase and induces cell death of Ph+ CML cells at a concentration of 10 nM, which is >10-fold more potent than imatinib. Results presented in our study also demonstrate that this compound targets a site that is different from the binding site of imatinib because ATP fails to compete with ON012380. Our results also suggest that ON012380 probably binds to the substrate binding site of the enzyme because a natural substrate, such as Crk, readily competes with ON012380 and interferes with its ability to inhibit BCR-ABL kinase. Furthermore, imatinib and ON012380 were found to synergistically inhibit wild-type BCR-ABL, suggesting that these two compounds bind to different sites on the enzyme.

Emerging data suggests that the majority of CML patients who achieve complete cytogenetic remission rarely achieve complete molecular remission (31, 32). This phenomenon appears to be due to the existence of rare resistant mutations within the pool of BCR-ABL+ cells, which, in the absence of imatinib, lack any growth advantage. It is now believed that imatinib treatment results in the elimination of wild-type BCR-ABL+ cells, leading to a cytogenetic remission. However, given adequate time, populations of CML cells harboring imatinib-resistant mutations expand, leading to a relapse of the disease (17). Our results show that ON012380 is very effective at inhibiting all of the imatinib-resistant mutants of BCR-ABL tested, including T315I. In addition to mutation within BCR-ABL, imatinib-resistance has also been recently attributed to overexpression and/or activation of Lyn (33, 34), which functions downstream of BCR-ABL. Studies have shown that inhibition of Lyn expression or activity in imatinib-resistant cells with short interfering RNA (35) or Src inhibitors reduced their proliferative capacity and ultimately induced apoptosis (33, 34). Because ON012380 is highly selective against BCR-ABL, it remains to be determined whether it will be effective against those samples in which Lyn function (as opposed to BCR-ABL mutation) mediates the resistance to imatinib. However, it is of interest to note that this compound also inhibits Lyn kinase activity in the nanomolar range (85 nM) (Table 2). It is therefore likely that ON012380 will also be effective against cells in which imatinib resistance is conferred by this pathway.

Another important feature of ON012380 is the very desirable safety profile that is not often seen in conventional chemotherapeutic agents. In mice, single doses of 300 mg/kg of ON012380 produced no toxicity. The low in vivo toxicity and the potent BCR-ABL inhibitory activity seen in in vitro and nude mouse assays bodes well for further development of this compound for the treatment of imatinib-resistant myeloid leukemias. Because this compound is highly effective in combination with imatinib, the lack of bone marrow toxicity may be beneficial for testing novel combinations for Ph+ CML, which may lead to complete molecular remission of the disease and prevent the appearance of imatinib-resistant forms of this disease over the course of time.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Onconova Therapeutics and the Fels Foundation.

Author contributions: K.G., S.J.B., S.C.C., M.V.R.R., and E.P.R. designed research; K.G., S.J.B., S.C.C., P.J., A.D.K., K.A.R., M.V.R.R., and E.P.R. performed research; K.G., S.J.B., M.V.R.R., and E.P.R. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; K.G., S.J.B., S.C.C., A.D.K., M.V.R.R., and E.P.R. analyzed data; and S.J.B. and E.P.R. wrote the paper.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: Ph, Philadelphia chromosome; CML, chronic myelogenous leukemia; STAT-5, signal transducer and activator of transcription 5.

References

- 1.Nowell, P. C. & Hungerford, D. A. (1960) Science 132, 1497. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rowley, J. D. (1973) Nature 243, 290–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeKlein, A., Van Kessel, A. G., Grosveld, G., Bartram, C. R., Hagemeijer, A., Bostooma, D., Spurr, N. K., Heisterkamp, N., Groffen, J. & Stephenson, J. R. (1982) Nature 300, 765–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heisterkamp, N., Stam, K., Groffen, J., de Klein, A. & Grosveld, G. (1985) Nature 315, 758–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Druker, B. J., Tamura, S., Buchdunger, E., Ohno, S., Segal, G. M., Fanning, S., Zimmermann, J. & Lydon, N. B. (1996) Nat. Med. 2, 561–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Druker, B. J, Sawyers, C. L., Kantarjian, H., Resta, D. J., Reese, S. F., Ford, J. M., Capdeville, R. & Talpaz, M. (2001) N. Engl. J. Med. 344, 1038–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah, N. P. & Sawyers, C. L. (2003) Oncogene 22, 7389–7395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.le Coutre, P., Tassi, E., Varella-Garcia, M., Barni, R., Mologni, L., Cabrita, G., Marchesi, E., Supino, R. & Gambacorti-Passerini, C. (2000) Blood 95, 1758–1766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahon, F.-X., Deininger, M. W., Schultheis, B., Chabrol, J., Reiffers, J., Goldman, J. M. & Melo, J. V. (2000) Blood 96, 1070–1079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weisberg, E. & Griffin, J. D. (2000) Blood 95, 3498–3505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sawyers, C. L. (2004) Genes Dev. 17, 2998–3010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu, C., Rahmani, M., Conrad, D., Subler, M., Dent, P. & Grant, S. (2003) Blood 102, 3765–3774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosee, P. L., Corbin, A. S., Stoffregen, E. P., Deininger, M. W. & Druker, B. (2002) Cancer Res. 62, 7149–7153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoover, R. R., Mahon, F.-X., Melo, J. & Daley, G. Q. (2002) Blood 100, 1068–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang, M., Dorsey, J. F., Epling-Burnett, P. K., Nimmanapalli, R., Landowski, T. H., Mora, L. B., Niu, G., Sinibaldi, D., Bai, F., Kraker, A., et al. (2002) Oncogene 21, 8804–8816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warmuth, M., Simon, N., Mitina, O., Mathes, R., Fabbro, D., Manley, P. W., Buchdunger, E., Forster, K., Moarefi, I. & Hallek, M. (2003) Blood 101, 664–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah, N. P., Tran, C., Lee, F. Y., Chen, P., Norris, D. & Sawyers, C. L. (2004) Science 305, 399–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rovera, G., Valtieri, M., Mavilio, F. & Reddy, E. P. (1987) Oncogene 1, 29–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ymer, S. W., Tucker, Q. J., Sanderson, C. J., Hapel, A. J., Campbell, H. D. & Young, I. G. (1985) Nature 317, 255–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Myers, R. M., Sheffield, V. C. & Cox, D. R. (1989) in PCR Technology, ed. Erlich, H. A. (Stockton, London), pp. 61–70.

- 21.Kumar, A., Baker, S. J., Lee, C. M. & Reddy, E. P. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 6631–6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laemmli, U. K. (1970) Nature 227, 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reddy, E. P. & Reddy, M. V. R. (2002a) U.S. Patent 6541475.

- 24.Reddy, E. P. & Reddy, M. V. R. (2002b) U.S. Patent 6486210 B2.

- 25.Reddy, E. P. & Reddy, M. V. R. (2003) U.S. Patent 6599932 B1.

- 26.O'Dwyer, M. E. & Druker, B. J. (2001) Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 1, 49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cleland, W. W. (1977) Adv. Enzymol. 45, 273–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corbin, A. S., Buchdunger, E., Pascal, F. & Druker, B. J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 32214–32219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Azam, M., Latek, R. L. & Daley, G. Q. (2003) Cell 112, 831–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levitzki, A. (2000) Topics Curr. Chem. 211, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hughes, T. P., Kaeda, J., Branford, S., Rudzki, Z., Hochhaus, A., Hensley, M. L., Gathmann, I., Bolton, A. E., van Hoomissen, I. C., Goldman, J. M. & Radich, J. P. (2003) N. Eng. J. Med. 349, 1423–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Druker, B. J. & Lydon, N. B. (2000) J. Clin. Invest. 105, 3–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donato, N. J., Wu, J. Y., Stapley, J., Gallick, G., Lin, H., Arlinghaus, R. & Taipaz, M. (2003) Blood 101, 690–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Donato, N. J., Wu, J. Y., Stapley, J., Lin, H., Arlinghaus, R., Aggarwal, B., Shishodin, S., Albitar, M., Hayes, K., Kantarjian, H. & Taipaz, M. (2004) Cancer Res. 64, 672–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ptasznik, A., Nakata, Y., Kalota, A., Emerson, S. G. & Gewirtz, A. M. (2004) Nat. Med. 10, 1187–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.