Abstract

Exocytosis depends on cytosolic domains of SNARE proteins but the function of the transmembrane domains (TMDs) in membrane fusion remains controversial. The TMD of the SNARE protein synaptobrevin2/VAMP2 contains two highly conserved small amino acids, G100 and C103, in its central portion. Substituting G100 and/or C103 with the β-branched amino acid valine impairs the structural flexibility of the TMD in terms of α-helix/β-sheet transitions in model membranes (measured by infrared reflection-absorption or evanescent wave spectroscopy) during increase in protein/lipid ratios, a parameter expected to be altered by recruitment of SNAREs at fusion sites. This structural change is accompanied by reduced membrane fluidity (measured by infrared ellipsometry). The G100V/C103V mutation nearly abolishes depolarization-evoked exocytosis (measured by membrane capacitance) and hormone secretion (measured biochemically). Single-vesicle optical (by TIRF microscopy) and biophysical measurements of ATP release indicate that G100V/C103V retards initial fusion-pore opening, hinders its expansion and leads to premature closure in most instances. We conclude that the TMD of VAMP2 plays a critical role in membrane fusion and that the structural mobility provided by the central small amino acids is crucial for exocytosis by influencing the molecular re-arrangements of the lipid membrane that are necessary for fusion pore opening and expansion.

Introduction

The release of neurotransmitters and hormones occurs by regulated exocytosis which consists of the fusion of the membrane of vesicles with the plasma membrane1. The SNARE proteins, a set of evolutionarily conserved proteins, form the core machinery for membrane fusion. During exocytosis, the cytosolic domains of the plasmalemmal proteins SNAP25 and syntaxin-1 interact with the vesicular protein VAMP2 to form the SNARE complex. The SNARE complex folds from the N- to C-terminal as a zipper, which brings the two adjacent membranes together. The resulting mechanical stress is believed to be transduced into membrane fusion via the juxtamembrane domain2. The molecular basis of membrane fusion and the associated lipid rearrangement remain poorly understood. It involves a series of intermediate steps such as stalk formation, hemifusion (fusion of adjacent membrane layers) prior to fusion pore opening and expansion3. These intermediate steps also imply changes in membrane tension and pressure as well as in local SNARE protein concentration4, 5.

Whereas the link between structure and function of the soluble cytosolic SNARE domains is well understood, much less is known about the role of the transmembrane domains (TMDs). Previous studies on potential function of the TMDs in fusion have provided contradictory results. The TMD of VAMP2 or homologues could be replaced by long-chain lipids or unrelated transmembrane domains6–9 and single point mutations did not affect exocytosis10, although some changes in dimerization were observed in vivo 11. In addition, replacement of the VAMP2 TMD by a lipid-anchored domain was found to be without effect on exocytosis when measurements were made at a supraphysiological (8 mM) extracellular Ca2+ concentration12. However, exocytosis was reduced by 80% at a more physiological Ca2+ concentration (2 mM). The latter observations raise the interesting possibility that the TMDs may play a role in exocytosis that extends beyond being merely a membrane anchor. This is further supported by a recent work from Dhara and colleagues who replaced half of VAMP2 TMD and showed altered fusion pore kinetics10.

The concept that the VAMP2 TMD influences exocytosis is suggested by two pieces of evidence: (1) Synthetic peptide containing alternating leucines and valines as well as helix-breaking residues recapitulate the physico-chemical properties of VAMP2 TMD and are fusogenic in model bilayers13–16; and (2) although membrane lipid mixing persists in reconstituted and cellular systems after replacement of the TMD with lipids or unrelated transmembrane protein sequences, the opening and lifetime of the fusion pore opening is strongly reduced17–20.

VAMP TMDs exhibit α-helical and β-sheet conformation in model membranes depending on the peptide/lipid ratio15, 21, a parameter that increases during membrane fusion4, 22, 23. This structural flexibility correlates with an increased fusogenicity13–15. The VAMP TMDs are capable of both vertical24 and lateral movements21, 25, 26 within the lipid membrane. Such movements require local peptide unfolding/refolding and may result in perturbation of the lipid reorganization that precedes fusion pore formation. These observations suggest a potential role of the TMD in membrane fusion but the precise mechanisms involved remain unknown. Understanding of fusion pore regulation is of fundamental importance and may also reveal the molecular basis of human diseases27.

Results

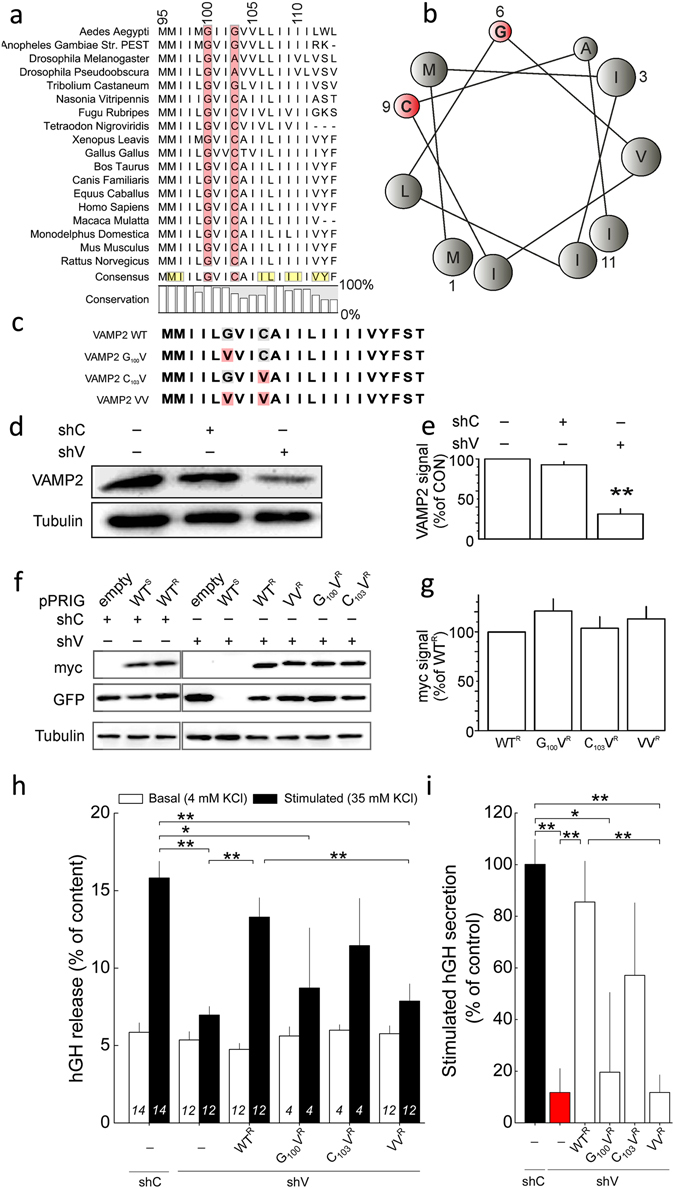

Conserved small amino acids in VAMP2 transmembrane domain

To define targets for mutagenesis, we compared VAMP2’s TMD across several species (Fig. 1a). VAMP2 TMD is dominated by repetition of hydrophobic residues such as leucine (L), or β-branched hydrophobic isoleucine (I) and valine (V). Phylogenetic comparison reveals the conserved presence of a tiny amino acid such as glycine (G), in VAMP2 at position 100. G is followed three residues away by a second tiny residue which is either a glycine (G), cysteine (C) or an alanine (A). The helical wheel projection of the consensus sequence (MMIILGVICAIILIIIIVYF, Fig. 1a) indicates that these residues localize to the same side of the α-helix (Fig. 1b) and are framed by isoleucines, leucines and valine/tyrosine (Fig. 1a, yellow). The high degree of conservation of these residues points towards functional importance16. Indeed, in silico molecular dynamics and structural data suggest that they produce a kink in protein that decouples the N-terminal and C-terminal halves of the TMD28, 29. Thus, mutations that reduce backbone mobility at this position are predicted to affect hormone secretion. To this end, we mutated G100 and C103 into valines, singly or in combination (G100V, C103V and G100V/C103V (VV)) (Fig. 1c). From a structural dynamics perspective, this β-branched amino acid should make the carbon backbone more rigid and in turn reduce mobility30.

Figure 1.

Conserved small residues in the N-terminal portion of the transmembrane domain of VAMP2 have a role in exocytosis. (a) Phylogenetic comparison of the VAMP2 transmembrane domain. The highly conserved small amino acids at the position 100 and 103 are highlighted in red. In the consensus sequence, residues that localize on the same aspect of the helical structure as G100 and C103 are presented in yellow. (b) Helical wheel presentation of the N-terminal half of the transmembrane domain highlighting the clustering of small (red) to medium-sized residues on a single face. (c) Sequences of wild-type and mutant TMDs; point mutations are highlighted in red. Mutations of small residues in the transmembrane domain (TMD) inhibit secretion in PC12 cells. Effects on hormone secretion were determined for mutants of the VAMP2 TMD after knock-down of endogenous VAMP2. (d) Transient expression of shRNA against VAMP2 (shV) but not control shRNA (shC) reduces expression of VAMP2 in PC12 cells. Tubulin immunoreactivity is shown for comparison. Full blots are given in Supplemental Fig. 8. (e) Quantification of silencing efficiency of shC and shV on endogenous VAMP2 as indicated. Data have been normalised to control conditions (no transfection). N = 3, **p < 0.01. (f) Re-expression of shRNA-resistant VAMP2. Cells were co-transfected with a plasmid bearing shC or shV, a bicistronic plasmid expressing either eGFP alone (pPRIG empty) or both eGFP and VAMP2. Wild-type VAMP2 was either sensitive (WTS) or resistant (WTR) to shV. All mutants were resistant to shV (VAMP2R). Full blots are given in Supplemental Fig. 8. (g) Quantification of re-expression of exogenous VAMP2Rs normalised to control (WTR). N = 3. (h) Reconstitution of depolarization-induced secretion. PC12 cells were transiently co-transfected with a plasmid expressing the human growth hormone (hGH), shC or shV, and the indicated VAMP2R (WTR or mutant in the TMD). Basal and stimulated hGH secretion are given. Mean values ± S.E.M., N as indicated. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 (ANOVA and Bonferroni). (i) Same data as g presented as percentage of reconstitution of stimulated secretion. Statistics as in h.

Mutations in VAMP2 TMD reduce hormone secretion

The mutants were first tested in rat pheochromocytoma PC12-cells, a widely used model to study regulated exocytosis. Here, the expression of endogenous VAMP2 was suppressed using an shRNA specific for VAMP2 (shV; Fig. 1d; full blots see Supplementary Data) and was compared to a control shRNA (shC). ShV down-regulates endogenous VAMP2 expression by nearly 70% whereas shC was without effect (Fig. 1e). We attribute remaining VAMP2 to non-transfected PC12-cells (see Methods). We next expressed exogenous VAMP2 (mutant and wild-type [WT]) rendered resistant to shV (indicated by an R) by introducing six silent mutations. The resulting constructs are referred to as WTR, G100VR, C103VR, VVR (Fig. 1f). These exogenous shV-resistant forms of VAMP2 were expressed concomitantly from a single plasmid with a separate GFP (to detect transfected cells). Exogenous VAMP2s contained also an N-terminal myc-tag. The expression of the exogenous WT VAMP2, either sensitive (WTS) or resistant (WTR) to shV, is not modified by the co-transfection with shC (Fig. 1f). When WTS was co-transfected with shV, its expression was abolished as was the expression of GFP (both WTS and GFP are translated from the same mRNA). By contrast, when the shV-resistant constructs were co-expressed with shV, both VAMP2 and GFP expression was unaffected (Fig. 1f). The expression of the different exogenous VAMP2s was similar for all constructs (Fig. 1f,g). For all experiments, the reporter used to measure functional consequences of such mutations is co-transfected which excludes the interference of non-transfected cells in regard to the interpretation of the data (see Methods).

We next examined the subcellular localization of the different shV-resistant VAMP2 constructs using the same transfection protocol as for functional assay. Cells were co-transfected with plasmids expressing VAMP2 constructs of interest, the shV and the neuropeptide Y (NPY) fused to Red Fluorescent Protein (RFP, i.e. NPY-RFP) as a marker for the Large Dense Core Vesicles (LDCVs) (Suppl. Fig. S1). VAMP2 WTR as well as the mutants co-localized with NPY-RFP, indicating correct targeting to the secretory granules (Suppl. Fig. S1).

To analyze the functional consequences of the VAMP2 mutations in the TMD, we explored the capacity to restore hormone secretion in cells in which endogenous VAMP2 had been down-regulated. For this assay, the reporter used is the human growth hormone (hGH), which is co-secreted from the LDCV (Fig. 1h,i) but not expressed in non-transfected cells. Secretion was stimulated by membrane depolarization ([K+]o 35 mM for 10 min), thereby activating voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Depolarization increased hGH release almost 3-fold above basal (Fig. 1h). Whereas down-regulation of endogenous VAMP2 strongly reduced [K+]o-stimulated secretion, expression of WTR rescued depolarization-evoked secretion to levels not different from control cells. Expression of G100VR and C103VR only partially restored [K+]o-induced secretion and the VVR mutant was unable to support depolarization-evoked exocytosis altogether. For display, the stimulated hGH secretion normalized to the control condition (shC) is summarized in Fig. 1i. These data suggest that mutations in the TMD of VAMP2 have strong functional consequences and that this applies especially to G100 (the most conserved residue, Fig. 1a).

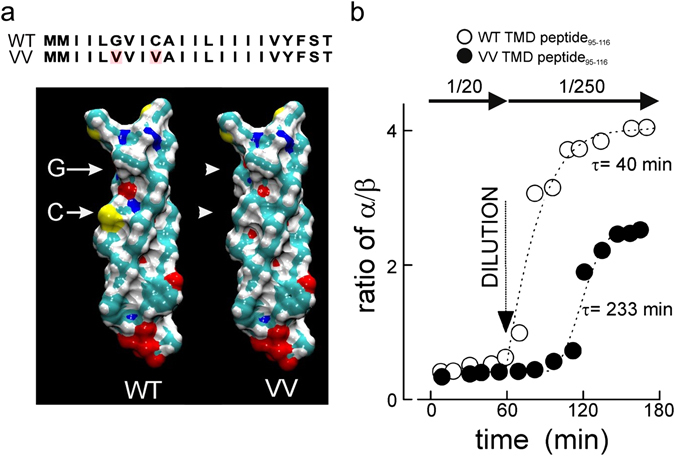

The small residues in the transmembrane domain are required for structural dynamics

Figure 2a, shows the predicted 3D α-helical structures of wild-type and mutant TMDs. The tiny amino acid G100 indents the α-helix (arrow in Fig. 2a) and may provide flexibility. The substitution of G100 by V tends to fill this indentation (Fig. 2a, VV, upper arrowhead). By contrast, substitution of only the second small amino acid, C103, by valine has less dramatic effects on the 3D organization (Fig. 2a, VV, lower arrowhead). If the indentation that results from G100 is functionally important, then mutations should affect the structural behavior of VAMP2 TMD and the β-branched valine should rigidify the carbon backbone30.

Figure 2.

The VV mutation reduces structural flexibility of the VAMP2 TMD. (a) Sequences and space-filling models of the transmembrane domain of the WT and VV mutant VAMP2 as an α-helix. Yellow designates sulphur, green carbon, white hydrogen and red oxygen. Arrows designate positions of G100 and C103, arrowheads point to the volume changes in the mutated sites. (b) ATR–IR spectra of the synthetic peptide VAMP295-116 (WT or VV mutant) in a lipid multi-bilayer (DOPC) were obtained at a peptide/lipid ratio of 1/20 at room temperature. After 1 h peptides were diluted with DOPC to a peptide/lipid ratio of 1/250 and structural changes measured for 2 h at room temperature. The ratios of α-helices vs β-sheets are given for wild-type (○) or the VV mutant (●). The curves were obtained fitting exponential growth. The time constants (τ) are given next to the curves.

To evaluate the effect of mutations on conformation and structural dynamics, we employed physicochemical approaches that allow dynamic studies of conformational changes and protein-lipid interactions in model membranes. We first tested structural mobility of the TMD alone using synthetic peptides (VAMP295-116) and focused on the VAMP2 VV mutant as it had the most pronounced biological effect (see Fig. 1h). Attenuated Total Reflectance-Fourier Transformed Infra-Red spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR) enables quantitative measurements of the protein structure within lipid bilayer membranes. For display, data are expressed as the ratio between α helices and β sheets. The peptides were mixed with lipids at an initially fixed ratio of 1:20 (Fig. 2b) and at this ratio both WT and VV-TMDs are mainly present as β sheets with an α/β ratio of ~0.4. However, when the peptide/lipid ratio is lowered to 1:250 by addition of lipids, the α/β-ratio increased ten-fold with a time constant (τ) of 40 min reflecting now mainly α-helical conformation. Similar dynamics were previously observed for VAMP121, 26. The time constant is slower than those generally measured in reconstituted fusion assays but the latter are conducted at 35 °C20, 31 and not at 22 °C as here. The conformational changes in the VV-TMD peptide were considerably smaller (α/β-ratio: 2.5) and occurred with ~6-fold slower kinetics (τ = 233 min) as compared to the wild- type upon lowering of the peptide/lipid ratio.

These observations suggest that the VV mutant has a reduced capacity to undergo conformational changes. We extended these observations using polarization modulation infrared reflection-adsorption spectroscopy (PMIRRAS) (Fig. 3). This provides qualitative information on the conformational dynamics of the TMD and allows the experimental control and variation of variables such as pressure that translates also into protein concentrations32 both expected to vary during membrane fusion4, 5, 22, 23. Since artificial bilayer formation is unstable and often results in triple layers, this technique employs lipid monolayers, but offers the possibility to use full-length protein. The proteins are embedded in a model membrane, which is exposed to variable lateral pressures to mimic the effects of varying the local concentration of VAMP2 in the membrane and of the physical stress known to be important during membrane during fusion5. The PMIRRAS spectra of the WT TMD at low lateral pressure (Fig. 3ai, black curve) showed a peak at 1630 cm−1 and a shoulder at 1653 cm−1, indicating a mixture of α-helices and β-sheets. Compression of the lipid layer containing WT protein increased absorbance (reflecting increased local protein concentration), which was particularly pronounced at 1630 cm−1, indicating an increase β-sheet configuration (red curve). These observations using the full-length protein confirmed the measurement obtained with the peptide using ATR and bilayers. These changes were fully reversible upon decompression (Fig. 3bi).

Figure 3.

The VV mutations in VAMP2 TMD reduce structural dynamics. Structural features of VAMP2 WT or VAMP2 VV full-length proteins were measured by infrared spectroscopy (PMIRRAS) in a Langmuir through at different lateral pressure. Note that increases in pressure increase local protein concentrations and peptide/lipid ratios. All experiments were performed at room temperature. Full-length proteins were embedded in DMPC monolayer at the protein/lipid ratio of 1/50 (Comparable results were obtained at peptide/lipid ratios of 1/20, data not shown). α-helical conformations and β-sheets conformations were detected at 1653 cm−1 and 1630 cm−1, respectively. (a) Structural behaviour of either VAMP2 WT or VV-TMDs during compression of the DMPC monolayer (ai and aii, respectively). (a i) Starting from a low lateral pressure (5 mN.m−1, black curve), a shoulder at 1653 cm−1 (corresponding to α helices) was detected. During compression to 44 mN.m−1, this shoulder becomes less prominent (red curve, arrowhead). (a ii) Identical procedure performed with VV from 4 mN.m−1 (black curve) to 55 mN.m−1 (red curve). Note the persistence of the shoulder (arrowhead) at high pressure. (b) Structural behaviour of either VAMP2 WT or VV-TMDs during decompression of the DMPC monolayer (bi and bii, respectively). (b i) To facilitate comparison, the high pressure curve from A has been superimposed (red traces). Decompression of the monolayer from 44 to 4 mN.m−1 restores the α helix shoulder (bi, blue curve, arrowhead), whereas decompression from 55 mN.m−1 to 4 mN.m−1 on membrane containing VV does not change the absorbance curve (b ii, blue curve and arrowhead).

We repeated these measurements with the VAMP2 VV mutant (Fig. 3aii–bii). As for the WT, compression increased the local concentration (increased absorbance) but had minor effects on the shape of the spectrum. The peaks at 1653 cm−1 and 1630 cm−1 increased to the same extent, indicating that in contrast to the WT transition from α-helical into β-sheet organization does not occur (Fig. 3aii). Unlike what was seen for the WT protein, the absorbance did not decrease upon decompression (Fig. 3bii). This indicates that the mutant VAMP2 has a reduced ability to undergo a conformational change. Note also that absorbance remains elevated after pressure reduction suggesting that the VV protein-lipid monolayer (unlike the one containing WT) does no longer relax. The intermediate mutants (G100V and C103V) were also analyzed (Supplementary Fig. 2) and also exhibited a tendency to decreased conformational changes.

Collectively, these data indicate that protein/lipid ratios strongly influence secondary structure on VAMP2 TMD and in a reversible manner, analogous to what we reported for VAMP121, 26. The sensitivity to its environment is a remarkable physical property of VAMP and it is easy to see how both the pressure and protein concentration can vary at the fusion site and thereby modify TMD dynamics5.

The small residues in the transmembrane domain affect membrane fluidity

Exocytosis ultimately depends on the reorganization of lipid membranes at the fusion site. In PMIRRAS, persistence of elevated absorbance upon decompression of VV-mutant containing membranes suggests that the mutations modify the relaxation of the membrane after physical stress such as lateral pressure (see Fig. 3bii). We investigated the impact of VAMP TMDs on membrane fluidity using infrared ellipsometry. This optical and contact-free method enables characterization of material properties such as viscosity. We imaged membranes seeded with the different VAMP2 proteins by the same compression/decompression cycle as used for PMIRRAS (Fig. 4). At low lateral pressure (left column), the membrane is of homogenous thickness (as indicted by uniform grey colour). As pressure increases (middle column), brighter areas appear against a darker background. The shape of these bright areas provides information on the fluidity/rigidity of the lipid membrane: round shapes indicate great fluidity, whereas jagged shapes indicate rigidity (‘crystalline’ properties). For intermediate viscosities, elongated shapes without sharp angles are detected. Compression resulted in the appearance of bright areas for the WT and all mutant VAMP2s. Whereas the shapes of these domains are rounded/elongated for WT, shard-like structures are seen for VV mutants. Upon decompression, these changes were fully reversible for the WT but less so for the membrane containing VAMP2 VV. Quantitative analysis of images (Fig. 4b) demonstrates a decrease in fractal dimension for the VV mutant, reflecting the observed loss in meandering patterns. Membranes where intermediate mutants were embedded present also clearly a specific behavior (Supplementary Fig. 3). Membranes bearing C103V presented similar patterns and capacity to relax the system. On the other hand, shard-like structures appeared during compression of G100V mutant with incomplete ‘relaxation’ upon decompression, echoing the observations of VAMP2 VV.

Figure 4.

The VV mutation in VAMP2 TMD modifies the fluidity of the membrane. Viscosity of model membranes were imaged by ellipsometry in a Langmuir through using DMPC membranes and either VAMP2 WT or VAMP2 VV full-length recombinant protein. (a) Representative images from DMPC model membranes mixed with the indicated mutant (1/50 nominal peptide/lipid ratio) obtained by ellipsometry in a Langmuir trough. Images were taken at initial low lateral pressure (left panel), at maximal lateral pressure (middle panel) and after relaxation (to low pressure, right panel). Measured lateral pressures are given at the bottom left corner of each image (mN/m). For VAMP2 WT, during the increase of the lateral pressure, the DMPC membrane evolves from homogenous monolayer to a monolayer bearing distinctive domains of different thickness (clear and dark zones). At the maximal pressure (36 mN/m), the patterns (round shapes, no sharp angles) indicate regions of great fluidity. By decompressing the system, the membrane returns fully to its original homogeneity. By contrast, an increase of the lateral pressure on membrane containing VV leads to the formation of ‘jagged’ patches with many sharp angles, a mark of membrane rigidity (28 mN/m). These changes persist upon decompression. (b) Quantification of fractional dimension of images obtained in ellipsometry by using the box counting dimension (mean DB, a logarithmic factor which varies between 1 and 2). Mean ± S.E.M., n = 6; **2p < 0.01 (t-test).

In silico simulations indicate that the TMD configuration influences the flexibility of the juxtamembrane cytosolic linker and the SNARE motif33.We examined by immunoprecipitation whether mutant VAMP2 is able to form SNARE complexes and whether the dimerization properties of TMDs34 are altered (Supplementary Fig. 3). Within the limits of the assay used, we did not observe any differences between WT and VV mutant VAMP2, suggesting that both variants are equally likely to form SNARE complexes. Moreover, the VV mutant did not have an increased tendency to form dimers.

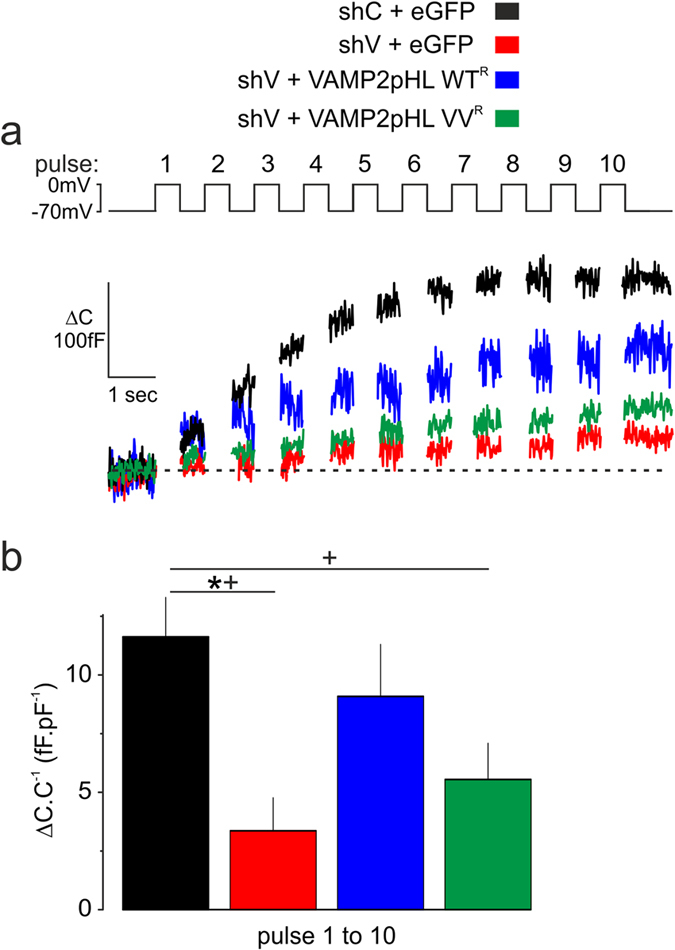

Effects of VAMP2 TMD mutant on exocytosis measured by membrane capacitance

The structural data show that G100 had a great effect on VAMP2 TMD dynamics, which not only affected the TMD itself but also the behavior of the surrounding lipid membrane. The double mutant (G100V/C103V, VV) had the strongest effect on secretion and structural dynamics. The impact of this TMD mutant on depolarization-evoked secretion was explored by capacitance measurements of exocytosis (Fig. 5) in the clonal β-cell line INS-1 832/13 (in the following referred to as INS1-cells), a model of Ca2+-dependent secretion35, 36.

Figure 5.

Effects of mutant VAMP2 TMDs on exocytosis measured by membrane capacitance in INS-1 832/13 clonal β-cells. Reconstitution of exocytosis by VAMP2 WT or VAMP2 VV and kinetics of vesicle pools were measured in INS-1 832/13 clonal β-cells expressing VAMP2pHL WTR or VAMP2pHL VVR after knock-down of endogenous VAMP2. (a) Representative traces of cumulative increase in membrane capacitance (ΔC in fF) elicited by 10 depolarizations (top panel) from −70 mV to 0 mV applied at 1 Hz. Cells were co-transfected with either shC + eGFP (n = 5, black trace), shV + eGFP (n = 6, red trace), shV + VAMP2pHL WTR (n = 6, blue trace) or shV + VAMP2pHL VVR (n = 10, green trace). (b) Quantification of the cumulative increase of capacitance normalized to cell capacitance (ΔC.C−1) at the end of the train. Although presenting a clear trend, the difference in the cumulative exocytosis measured in cells expressing either VAMP2pHL WTR or VAMP2pHL VVR did not reach statistical significance (ANOVA and Tukey, p = 0.093, *p < 0.05). However, differences became significantly evident when comparing the kinetics of exocytosis for WTR or VVR to those of the reference control shC (ANOVA and Dunnett, +, p < 0.05).

Similar to PC12-cells, endogenous VAMP2 expression was specifically knocked-down. The different constructs were expressed at comparable levels and colocalized with insulin in fixed cells or NPY-RFP in living cells (Supplementary Fig. 5a,b). Expression of the constructs was not associated with compensatory up-regulation of VAMP3 (Supplementary Fig. 5a), unlike what has previously been reported in chromaffin cells37. No expression of VAMP1 was detected in INS1-cells or non-differentiated PC12-cells as reported previously38, 39 (Supplementary Fig. 4D). It was ascertained that only some 4% of endogenous VAMP2 remain in co-transfected cells (Supplementary Fig. 6). Collectively, these considerations argue that responses observed reflect the behavior of the exogenously expressed VAMP2.

In control INS1-cells (transfected with shC and eGFP, included for the identification of successfully transfected cells), a train of ten 500-ms depolarizations from −70 mV to 0 mV (top panel, Fig. 5a) evoked a biphasic response with an initial large step increase in membrane capacitance, followed by progressively smaller increases (Fig. 5a, representative black trace). For analysis, changes in cell capacitance (ΔC) have been normalized to the initial cell capacitance to compensate for variations of cell size (i.e. ΔC.C−1, Fig. 5b,c). Silencing VAMP or expressing the mutants had no impact on cell size (not shown). The total increase in cell capacitance during the train is shown in Fig. 5b. After transfection with shV (again with eGFP), depolarization-evoked exocytosis was nearly abolished (Fig. 5a,b, red trace and column) but almost fully rescued in cells expressing WTR (Fig. 5a,b, blue trace and column), whereas VVR was ineffective (Fig. 5a,b, green trace and column), at least during the 10-s stimulation period used here. The inhibition of exocytosis cannot be attributed to reduced Ca2+ channel activity (Supplementary Fig. 7).

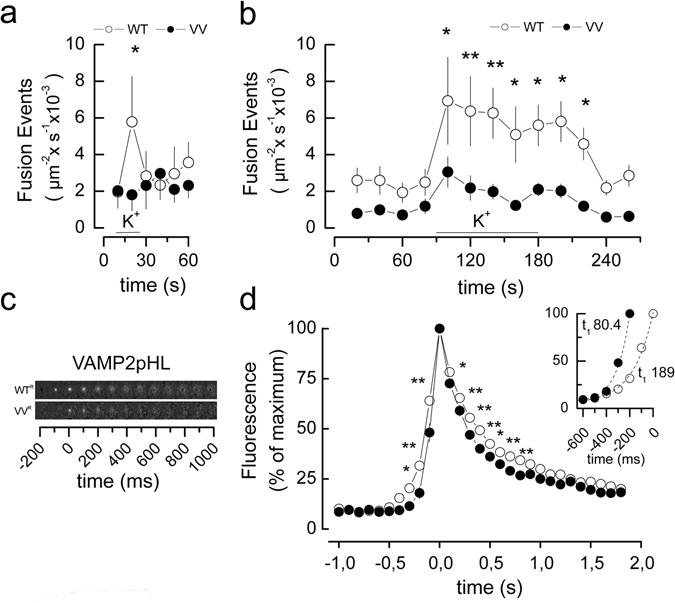

Effects of VAMP2 TMD mutant measured by TIRF imaging of exocytosis

We corroborated the observations on hormone secretion and capacitance measurements by total internal reflection microscopy (TIRF) to monitor release of docked granules40. To visualize vesicles undergoing fusion, we used VAMP2 WTR or VVR coupled with the pH-sensitive eGFP-pHluorin (VAMP2pHL; same as used in Fig. 5). For this probe fluorescence increases when the vesicular pH neutralizes during opening of the fusion pore41. Both measurements were performed in the presence of shV in PC12 and INS-1 832/13 cell lines (Fig. 6a,b). In PC12-cells expressing WTR, membrane depolarization (induced by 90 mM [K+]o) evoked a transient stimulation of exocytosis. Consistent with the hormone secretion measurements in Fig. 1h, expression of VVR instead of WTR abolished this stimulation whilst not affecting basal release. When the same type of experiment was conducted in INS1-cells expressing WTR, high-[K+]o (35 mM) depolarization resulted in a sustained stimulation of secretion. Stimulated secretion was strongly inhibited in cells expressing VVR. Basal secretion before elevation of [K+]o tended to be reduced in VVR-expressing cells but this effect did not attain statistical significance. Figure 6c shows TIRF images of representative fusion events recorded at different time points in cells expressing either WTR or VVR. We analyzed the kinetics of the fusion events and Fig. 6d shows averaged fluorescence increases associated with LDCV exocytosis. Whereas the increase to maximal fluorescence took ≈500 ms for VAMP2-WT vesicles, the delay was only 300 ms for the VVR vesicles resulting in distinct time constants and the decay of fluorescence following the peak was likewise slower for WTR than for VVR. In summary, the TIRF measurements using membrane-bound VAMP2pHL as probe indicate that the number of release events is much reduced in VVR cells and that exocytosis (once initiated) proceeds either more rapidly or the life-time of the fusion pore is reduced.

Figure 6.

The VV mutation in the TMD of VAMP2 alters exocytosis and fusion pore kinetics. Exocytosis and release kinetics were determined by near-field TIRF microscopy in PC12 and in INS-1 832/13 clonal β-cells expressing VAMP2 WT or the VAMP2 VV mutant after knock-down of endogenous VAMP2. (a) PC12 cells were transiently co-transfected with plasmids encoding VAMP2-pHluorin (WTR or VVR) and shRNA directed against VAMP2. Fusion events were recorded by TIRF microscopy and sum of fusion events per 10 s is given for cells stimulated by 90 mM [K+]o (WT, n = 6 cells, 237 events; VV n = 4 cells, 139 events total) *2p < 0.05 (Student’s t-test). (b) Same as in (a) but measurements performed on INS-1 832/13. Sum of fusion event per 20 s in transfected cells were stimulated by 35 mM [K+]o for 30 s (WT n = 9 cells, 1114 events total; VV n = 9 cells, 476 events total. *2p < 0.05; **2p < 0.01 (Student’s t-test). (c) Representative films of fusion events in INS-1 832/13 cells. The events are temporally synchronized to the frame of their maximum fluorescence. (d) Mean changes in normalized fluorescence immediately before and after exocytosis in INS-1 832/13 cells expressing either VAMP2pHL WTR (open circles) or VVR (closed circles). For display the fluorescent mean events were synchronized to their maximum fluorescence. Note narrower peak for VV as compared to WT. *2p < 0.05; **2p < 0.01 VAMP2 WT vs. VV (Student’s t-test). INSERT: Events synchronized for first event with a mean >10% of maximal fluorescence and curves fitted for first order exponential growth. Note shorter time constant τ for VV (closed circles) as compared to WT (open circles). The time constants τup for the fluorescence increases averaged 189 ± 28 ms for WTR and 80 ± 7 ms for VVR (p < 0.05; F-test). Similarly, the decay of fluorescence following the peak was slower for WTR (time constant τdown: 558 ± 57 ms) than for VVR (τdown: 315 ± 17 ms) (p < 0.05; F-test).

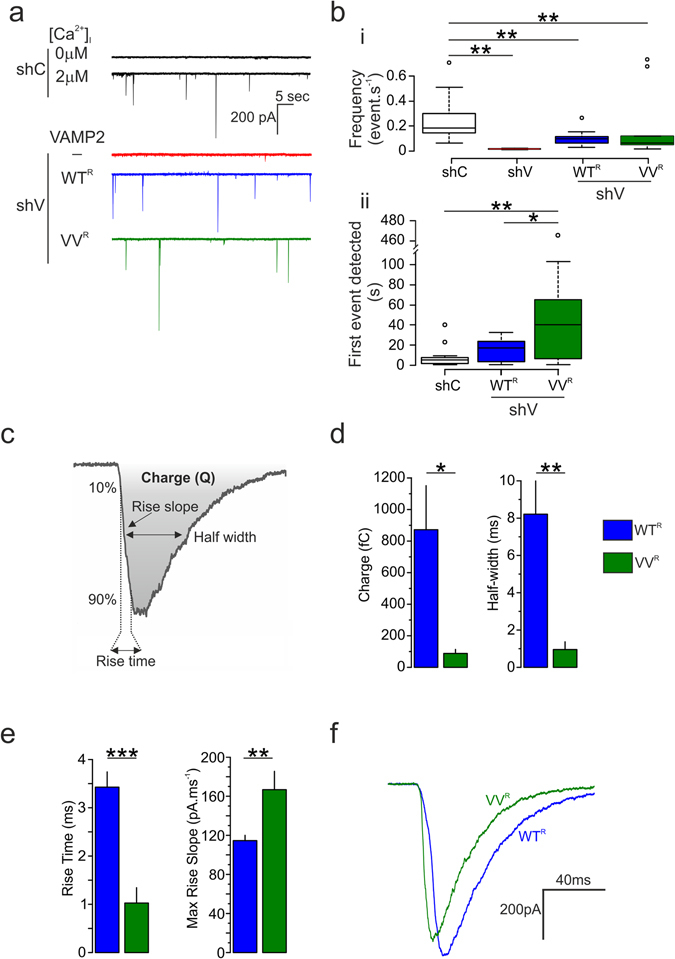

Effects of VAMP2 TMD mutant on the kinetics of the fusion pore

The TIRF measurements indicate that VVR influences the mechanics of fusion pore expansion. We used INS1-cells transfected with the ATP-sensitive P2X2 receptor (P2X2R) to monitor kinetics of single-vesicle exocytosis at a higher resolution27, 42, 43. No exocytotic events were observed when cells were infused with a Ca2+-free buffer (10 mM EGTA alone; Fig. 7a, grey trace). However, when the cells were infused with buffers containing 2 μM [Ca2+]i (mixture of 9 mM Ca2+/10 mM EGTA), exocytosis was observed (Fig. 7a, black trace). Knockdown of endogenous VAMP2 abolished Ca2+-induced exocytosis (Fig. 7a,b). Exocytosis in shV-treated cells was partially restored when VAMP2WTR or VAMP2VVR was expressed (Fig. 7a,b). No difference in the frequency was observed between the WTR and VVR constructs. (Fig. 7bi). However, the first fusion event was delayed by 20 s when cells expressed VAMP2VVR (Fig. 7bii). We quantified the charge and the half-width as well as the rise time and the maximum slope of activation (illustrated schematically in Fig. 7c). Values shown represent averages of the median for each cell. Charge and half-width were reduced by 85% in cells expressing the VAMP2 VV construct (Fig. 7d). The rise time was reduced by 70% and the maximum slope increased by 25% (Fig. 7e). Assuming that the reduction of charge does not reflect a reduction of vesicular ATP content, we hypothesize that VAMP2VV is unable to keep the fusion pore open and promotes kiss and run events rather than full fusion. Figure 7f shows representative WT and VV events with similar peak amplitudes. There were no significant differences between WT and shC events (not shown) for any of the parameters above. Thus, overexpression of VAMP construct per se does not affect fusion.

Figure 7.

VAMP2 G100/C103 influence fusion pore opening. Measurements of quantal release of ATP via P2X2 receptor mediated currents from INS-1 832/13 cells expressing VAMP2 WT (G100/C103) or VV (G100V/C103V) after knock-down of endogenous VAMP2. (a) Currents triggered by ATP release. Top traces show INS-1 832/13 cells transfected with shC (black trace) and infused with media containing 0 or 2 μM free calcium. The 3 bottom traces are from cells co-transfected with plasmid P2X2-YFP, shC or shV, and VAMP2-pHL (WTR or VVR), respectively (black, shC; red, shV + empty vector; blue, shV + VAMP2pHL WTR; green; shV + VAMP2pHL VVR). (b i) Frequency of events per second (ANOVA and Tukey shC vs. shV p = 0.004, vs WTR p = 0.004, vs. VVR p = 0.001; shC, 12 cells, n = 802 events total; shV, 6 cells, n = 30 events total; WTR 12 cells, n = 388 events; VVR, 8 cells, n = 695 events; °, outliers). (b) Response delay defined as time required for the first event to be detected (ANOVA and Tukey, shC = 4 ± 0.86 s, WTR = 14, 43 ± 3.21 s, VVR = 36.90 ± 11.48 s. (c) Schematic illustration of the charge, the 10% to 90% rise time, the rise slope, and the half width of the current generated by P2X2R. These parameters are measured for the fusion pore kinetics study. (d,e) Mean values of the medians for the charge, the half width (d) and rise time and its slope (e), respectively (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, t test). (f) Superimposition of currents of similar amplitude elicited from cells expressing VAMP2pHL WTR (blue) and VVR (green).

Discussion

We combined a structural analysis of VAMP2 transmembrane domain dynamics and a characterization of its potential cellular function. Biochemical, electrophysiological and optical approaches demonstrate that VAMP2 modified in the TMD region (G100V/C103V) is unable to restore exocytosis. Fine analysis revealed a reduced structural mobility of the TMD, an enhanced viscosity of the membranes as well as a delayed but more rapid fusion pore expansion. Even though we observed the most pronounced effect when both G100 and C103 were mutated into V, the single G100V mutation alone was able to alter the membrane viscosity and partially reduced the hormone release. This observation makes us hypothesize that the function of VAMP2 TMD during exocytosis is principally mediated by G100.

The critical role of G100 has not previously been detected in cellular system. This we attribute to two factors. First, in some studies, the glycine was replaced by residues that should not increase the structural rigidity of the TMD10, 44, 45. Second, toxins were used in some studies to inhibit the exocytosis supported by the endogenous VAMP2 but in such systems remaining endogenous TMD may dimerize and compensate for the effects of the studied mutations8, 11. Concomitant mutation of C103 to β-branched V further increased functional effects. We do not think that this could be explained by changes in intramembrane cysteine palmitoylation46 as a mutation of Cys to Leu does not alter the efficacy of VAMP210.

The profound and reversible structural transition of the native TMD (from α-helices to β-sheets) is a unique property of VAMP121, 26 and VAMP2 (current data). Previously the presence of β-sheets has only been observed for synthetic sequences or truncated VAMP215, 29. Our structural analysis was able to capture such dynamics for both the full-length protein and the corresponding TMD peptide. These findings argue that the structural dynamics represents a key property of the transmembrane domain.

Predicting or modeling the structural consequences of mutations is notoriously difficult47. The existence of a β-sheet conformation of the TMDs has been detected by previous spectroscopic approaches15, 21, 26, even in highly dehydrated membranes29 and its functional significance was perhaps not always appreciated because of the lack of dynamic measurements. The failure of in silico molecular simulations to predict a β-sheet conformation can be attributed to the constraints of parameter values. The dynamic measurements presented here suggest that the TMDs not only possess great structural flexibility, they also (via the changes in their structure) influence membrane viscosity, a property that easily can be envisaged to influence membrane fusion.

Several observations point towards the relevance of small residues such as the central glycine in TMD structure and function. Model peptides made of leucine-valine repetitions exhibit increased conversion from an α-helical to a β-sheet conformation upon introduction of a central glycine14. The significance of TMD leucines and valines is also suggested by the finding that they enhance fusogenicity and are statistically overrepresented in SNARE TMDs and viral fusion sequences16. Molecular simulations28, 33 and structural data25, 29 suggest that the TMD is actually composed of two halves with distinct tilt angles. These two halves are joined by G100, which functions as a molecular ‘hinge’. Most recently, it was demonstrated that replacement of either the total TMD or its N-terminal half (including G100/C103) by polyleucine or poly-isoleucine sequences changes the fusion pore kinetics10. Our data indicate that much smaller modifications of the protein (replacing only one or two residues) are sufficient to change structural dynamics along with fusion kinetics and specifically highlight the importance of G100 and C103 in TMD mobility, membrane viscosity, fusion pore initiation and expansion (Fig. 8). In view of the kink at G100 one may speculate whether it is the N- or C-terminal half of the TMD that moves primarily. Indeed, the N-terminal portion is probably rather immobile by its connection to the VAMP juxtamembrane domain interacting with charged cytosolic phospholipid head-groups48 and cognate SNARE linkers49. In contrast, the C-terminal half is splayed from the TMD of the cognate SNARE protein syntaxin49 and cholesterol, known to promote fusion pore opening50, has a further effect on the tilt25. Addition of charged residues at the C-terminal end restricts VAMP2 TMD mobility and reduces or delays fusion pore opening24, 51, 52 which was interpreted as a consequence of reduced vertical “pull” of the TMD into the membrane53. However, such a C-terminal modification will also restrict lateral mobility of the transmembrane domain and potentially prevents the tilt of angle accompanying the transition from an α helix to a β sheet conformation21.

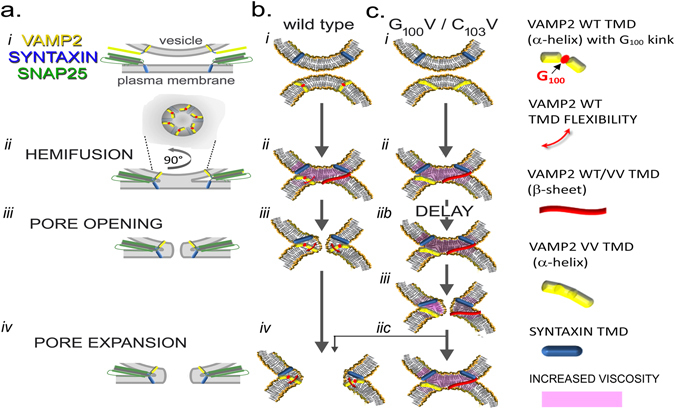

Figure 8.

Proposed model of conformation of VAMP2 transmembrane domain during exocytosis. The different steps of exocytosis are viewed from general scale with the presence of the SNARE cytosolic domain (a) and more focused on the TMD structure from VAMP2 WT (b) and VAMP2 VV (G100V/C103V) (c). Before vesicle docking, VAMP2 is uniformly distributed over the vesicle, corresponding to a low local concentration of VAMP2, and the TMDs are mainly in α-helical conformation (a i,b i, c i). Following docking, VAMP2 proteins concentrate at the fusion site (a ii). The increased local TMD concentration alters the peptide/lipid ratio and induces the switch of its conformation from an α-helical to a β-sheet conformation. The structural change is accompanied by a tilt of angle of the transmembrane domain from 30° to 54°21, promoting the lipid reorganisation and an increase of membrane viscosity (b ii,c ii). Once fusion has occurred and following lipid rearrangement, the SNAREs are localised on the same membrane (a iii). The decrease of the local concentration of VAMP2 and membrane tension results in the return to an α-helical conformation in the case of VAMP2 WT. This is accompanied by an increase of fluidity of the membrane that promotes the opening of the fusion pore for VAMP2 WT (b iii) and its subsequent expansion (a iv and b iv). The VV mutant has reduced capacity for reversible structural changes and is either lacks flexibility around G100 or is locked in the β-sheet conformation. This causes a delay in the fusion pore opening in the case of VAMP2 VV (c iib, c iii). The persisting increase in membrane viscosity does not permit further expansion of the pore and induces its premature closure in most cases (c iic). In some cases full fusion may occur as documented by recording of membrane capacitance.

Based on the findings reported here and taking previous observations into account54, we propose a model in which fusion proceeds sequentially via, stalk formation, hemifusion, and fusion pore opening (Fig. 8). The delay and alterations in flux kinetics place the action of G100/C103 at the level of the initiation of the fusion pore and at its further expansion. The subsequent opening and expansion of the nascent fusion pore constitutes the most-energy-demanding step and requires additional driving forces3. Prior to the docking/formation of the SNARE complex, VAMP2 is distributed across the vesicle membrane and the concentration of the transmembrane domains (TMDs) is low, favoring α-helical conformation (Fig. 8ai–ci). At the initiation of exocytosis, SNARE proteins localize at the fusion site (Fig. 8aii). The resultant increase in the concentration of the TMDs induces a change in peptide/lipid ratios and a conformational change of the VAMP2 TMDs ensues (Fig. 8bii). This may consist of partial helix destabilization and enhanced conformational mobility around G100 or - potentially, as extreme outcome –full transition from α-helices to β-sheets. We postulate that such conformational mobility is required to overcome the complex geometry and viscosity of lipid assembly during the transition from hemifusion to fusion pore opening (Fig. 8aiii–biii) and may promote lipid mixing. This step is delayed in the case of VAMP2 VV, which remains locked in its conformation and modifies the surrounding membrane properties (Fig. 8cii–ciib). Once the fusion pore opened, it expands further in the case of VAMP2 VV (Fig. 8aiv and biv). In contrast, in case of VAMP2 VV increased membrane viscosity and tension hinders further expansion and lead to premature closure of the pore in most instances (Fig. 8ciic) although full fusion may still occur in some instances as suggested by capacitance measurements (Fig. 5).

The molecular nature of the fusion pore is intensely debated55 and has variably been postulated to be either lipidic56, 57 or proteinaceous58, 59. It is implicit from the model we propose that the fusion pore is – at least partially – of lipidic nature. Regardless of the final outcome of this debate, our findings show an intimate interaction between the dynamics of the VAMP2 transmembrane domains via the central glycine and the fluidity of the lipid membrane. In turn, this interaction influences greatly the likelihood and speed of fusion pore opening and expansion.

Methods

Material

1,2-Dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phophatidylcholine (DMPC, CAS 8194-24-6) and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-Glycero-3-Phosphocholine (DOPC, CAS 4235-95-4) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. INS-1 832/13 cells were generously provided by Drs P Maechler and C.B. Wollheim (Geneva, CH)36. PC12 cells were obtained from ATCC and used for up to six passages. The following primary antibodies were used: polyclonal or monoclonal anti-myc (Sigma Aldrich, Saint-Quentin, France and Millipore, Molsheim, France respectively), monoclonal anti-VAMP2 (clone 69.1, Synaptic Systems, Göttingen, Germany), monoclonal anti-syntaxin (HPC1, Sigma), monoclonal anti-SNAP25 (Sternberger Monoclonals), polyclonal anti-VAMP1 (Santa Cruz, FL118) and anti-tubulin (BD Biosciences, Le Pont-De-Claix, France). The following secondary antibodies were employed: HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (GE Healthcare), CY3-coupled secondary anti-mouse, antibody, a Texas-red-coupled anti-guinea-pig antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch) and Alexa, 488 anti-rabbit antibody (Molecular Probes). The following antibodies and plasmids were generously donated: polyclonal anti-GFP (kindly provided by M. Rout, Rockefeller University, New York, NY, USA); NPY-mRFP (Dr. W Almers, Portland, USA) and pPRIG (Dr. Martin, Nice, France).

Molecular Cloning

To generate shRNAs against rat VAMP2, two 64-mer primers were synthetized according to a published sequence60, annealed and the synthetic dsDNA with cohesive ends was directly inserted into the vector pSUPER at BglII/HindIII sites, generating pSUPERVAMP2 plasmid (primers are listed below). As control shRNA, we used a pSUPERGL2 encoding shRNA against the firefly luciferase GL2. The whole H1 promoter-shGL2 sequence was taken from a lentiviral vector pLVTHMshGL2 (a kind gift from Dr. V. Haurie, University of Bordeaux, France) and substituted into pSUPER (Oligoengine, Seattle, WA, USA). The plasmid pBKCMV-mycVAMP2 was used as a PCR template in order to insert the myc-tagged rat VAMP2 cDNA sequence into the bi-cistronic vector pPRIGp61 at BamHI/XhoI sites. pPRIGp-mycVAMP2 vector was used to generate all the subsequent point mutations using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, Le Massy, France), starting with the generation of a shRNA resistant version, pPRIGp-mycVAMP2R, by introducing 6 silent mutations within the target for the siRNA.

The following primer were used: shVAMP2, sense: 5′GATCCCCGGACCAGAAGCTATCGGAACTTTCAAGAGAAGTTCCGATAGCTTCTGGTCCTTTTTA3′, antisense: 5′AGCTTAAAAAGGACCAGAAGCTATCGGAACTTCTCTTGAAAGTTCCGATAGCTTCTGGTCCGGG5′; VAMP2R wt, sense: 5′GGTCCTGGAGCGGGACCAAAAACTGAGCGAACTGGATGATCGC3′, antisense:5′GCGATCATCCAGTTCGCTCAGTTTTTGGTCCCGCTCCAGGACC3′;VAMP2R G100V, sense: 5′GATCATCTTGGTAGTGATTTGCGCC3′, antisense: 5′GGCGCAAATCACTACCAAGATGATC3′; VAMP2R C103V, sense: 5′GGGAGTGATTGTCGCCATCATCC3′, antisense: 5′GGATGATGGCGACAATCACTCCC3’; VAMP2R G100V/C103V, sense: 5′GATCATCTTGGTAGTGATTGTCGCCATCATCC3′, antisense: 5′GGATGATGGCGACAATCACTACCAAGATGATC3′.

For TIRF and capacitance experiments, mycVAMP2R cDNA was also subcloned into pCDNA3 in frame (at its 3′ end) with the encoding sequence for TEVPHL, i.e. TEV protease-specific cleavage site followed by the pHluorin41 encoding sequences. The plasmid encodes full-length, non-truncated VAMP2 followed by the protease sensitive linker SMGSGGDYDIPTTENLYFQGELKTTVDAD and the full-length ecliptic phluorin lacking its first amino acid (M). The linker is predicted to form essentially a random coil and potentially an extended sheet for the last six amino acids61. Point mutations within the transmembrane domain were introduced using either pPRIGp-mycVAMP2R or pCDNA3-mycVAMPR-PHL as template for site-directed mutagenesis. All constructs were verified by sequencing of both strands. For recombinant protein production and purification, the corresponding cDNA VAMP2 sequences (EcoRI-XhoI fragments) were taken from recombinant pPRIGp vectors and subcloned into pGEX4T2 vector.

Protein Expression and Purification

Transmembrane domain peptides of 22 amino acid residues (VAMP295-116) were synthesized and purified as previously reported21. Recombinant GST-VAMP2 (rat) was produced in E. coli BL21 (DE3), solubilized in Triton-X100 containing buffer and bound to glutathione beads62. After exchanging the detergent for 0.8% octylglucoside, VAMP was eluted from the beads by thrombin cleavage, concentrated and further purified by FPLC (Superdex75). Purified proteins were stored at −80 °C in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.8% octylglucoside and 10% glycerol26 (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Cell Culture, Transient Cotransfections and Immunoblots

Cell culture of INS-1 832/13 or PC12 cells and secretion assays were performed as previously described63. Cells were periodically checked for mycoplasma and found to be negative. Cells were transfected as published63 and cultured for three days before assays. Upon co-transfection of PC12 cells with shV, VAMP2 constructs and NPY, 82 ± 3% of transfected cells co-expressed VAMP2 constructs and NPY, 13% ± 3% only NPY and 5, 3 ± 2% only VAMP2 (n = 8 coverslips). SDS-Page and immunoblots were performed as described62. Immunoblots were developed using an ECL system and images were taken (Fluorochem 8000) at different time points to ensure linearity. Signals were quantified using Alfa-Ease FC software (Alpha Innotech) after suppression of local background and normalized to tubulin immunoreactivity from the same immunoblot experiment.

Immunoprecipitation

INS-1 832/13 cells were harvested 48 h after transfection. Immunoprecipitation of GFP fused to VAMP was realized using GFP-Trap®_MA beads (Chromotek; Martinsried/Germany). Cells were lysed in 250 µl of the following buffer: 20 mM HEPES pH 7.3, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors. After 30 min lysis on ice cells were centrifuged 10 min at 20.000 g. Supernatants (~230 µl) were diluted with 300 µl of lysis buffer without TritonX-100. 20 µl of beads were washed 3 times in the same buffer and 500 µl of diluted extract were applied onto it. After 2 h of head over head incubation at 4 °C, beads were washed 3 times and resuspended in 100 µl of 2X SDS-PAGE buffer.

Immuno-isolation of Transfected Cells

Immuno-isolation was performed similar as described previously64. 72 h hours after transfections INS832-13 cells were harvested and suspended in PBS containing 2 mM EDTA. Aliquots (total fractions) were taken before adding anti-CD8 Dynabeads (Thermofisher, Waltham, MA, USA) equilibrated in PBS-EDTA. Cells and Dynabeads were incubated at 4 °C for 30 min and supernatants were removed by magnetic trapping (yielding the “unbound” fraction). Beads were subsequently washed 3 times with PBS-2 mM EDTA before being suspended in Laemmli sample buffer (providing the “bound” fraction). Total, unbound and bound fractions (2.5%, 2.5% and 50% of each fraction respectively) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE on 12% polyacrylamide gels followed by Western blotting. PVDF membranes were probed with anti-VAMP2, anti β-tubuline and anti-GFP antibodies. VAMP2 expression levels were determined either using a standard curve of purified recombinant VAMP2 or serial dilutions of samples. Images were quantified using Alfa-Ease FC software (Alpha Innotech) after suppression of local background.

Secretion Assays

PC12 cells were washed twice with glucose containing Krebs-Ringer buffer (KRBG), composed of (mM): 135 NaCl, 3.6 KCl, 3.5 NaHCO, 0.5 NaH2PO4, 0.5 MgCl2, 1.5 CaCl2, 25 glucose, 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 with NaOH, supplemented with 0.1% w/v of BSA. Secretion was measured during 10 min either at normal 3.6 mM or elevated 35 mM [K+]o. When [K+]o was increased, [Na+] was simultaneously lowered to maintain iso-osmolarity. Note that these K+ concentrations are expected to result in lower secretion rates than the concentrations of 48 or 90 mM widely used. Supernatants were centrifuged and human growth hormone (hGH) determined by ELISA (Roche Diagnostics, Meylan, France).

Transmembrane Domain Comparisons

Among the sequences of VAMP2 collected by Kloeppers et al.65, those with well delineated transmembrane domains were retained and alignments were performed using Vector NTI 11 (Invitrogen, Life Technologies SAS, Villebon sur Yvette, France).

Electrophysiology

The electrophysiological recordings were performed using and EPC-10 amplifiers and the Pulse software (version 8.30 or later; Heka Elektronik, Lambrecht, Germany). Exocytosis was detected as changes in cell capacitance, which was estimated by the Lindau-Neher technique implementing the “Sine + DC” feature of the lock-in module66. The amplitude of the sine wave was 20 mV and the frequency set as 500 Hz The standard whole-cell configuration was used, and the pipette-filling medium contained (mM) 125 Cs-glutamate, 10 CsCl, 10 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 0.05 EGTA, 3 Mg-ATP, 0.1 cAMP, and 5 HEPES (pH 7.2 using CsOH). Ten 500 ms depolarizations of from −70 to 0 mV were applied at a frequency of 1 Hz. The responses were measured as the increase in membrane capacitance between the prestimulatory level and the new steady-state value and were normalized by the size of the cell35, 67.

Kinetics of ATP Released Using P2X2 Receptor and Current Analysis

Transfected INS1-832/13 cells were patched in whole cell configuration with an intra-pipette buffer containing 115 mM CsCl, 10 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM HEPES, 3 mM Mg-ATP, 0 mM (for the control) or 9 mM CaCl2 and 10 mM EGTA (calculated free [Ca2+]i: 0 or 2 μM), pH 7.15 (NaOH). Traces were exported to Clampfit to analyze the rise time (t10–90%), and the rise slope of each event. Events with an amplitude between 20 pA and 700 pA were analyzed to avoid interference from the noise background and compound exocytosis.

Confocal and TIRF Imaging

For immunocytochemistry and imaging by confocal laser microscopy, cells were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and processed as reported62, Confocal images were acquired as 8 bit images (308 × 308 pixels, 5.28 µm × 5.28 µm) using a Zeiss LMS 510 Meta confocal laser microscope and a Plan-Apochromat 63x/1.4 OilDIC objective with the following wavelengths and emission filters: λex 405 nm, BP420-480; λex 488 nm, LP505; λex 543 nm, BP560-615; λex 633 nm, LP650. Image analysis was performed after thresholding using the plugin Coloc2 for ImageJ68.

For TIRF microscopy, transfected cells were observed using an Olympus microscope (IX 71) equipped with TIRF illumination fed with Dual Color Laser (Cobolt, Sweden) (473 and 561 nm wavelengths). Images were taken with a 60 × 1.49 NA TIRF objective. Evanescent field properties were controlled with 0.2 µm TetraSpeck fluorescent microspheres (Invitrogen) before each experiment. Fluorescence emission were filtered using a 525/50 m band-pass filter (Chroma Technology) and images were acquired continuously (100 ms exposure time per frame) with an EMCCD camera (QuantEM, Roper Scientific, France) (1 pixel = 178.9 nm) for at least one minute. INS-1 832/13 Cells were stimulated by the main perfusion of 35 mM KCl KRBG. PC12 cells were stimulated by local perfusion with 90 mM KCl in modified KRBG (containing 50 mM NaCl) using an electrovalve.

For image treatment, the brightest pixel of the fusion event was determined as the spatial and temporal origin of the event using Matlab (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA). Automatic detection of the fusion event is based on the pattern of VAMP2-pHL fluorescence variations during exocytosis. This is typically composed by an increase in fluorescence intensity for two frames (0.2 s) followed by a decrease over maximally seven subsequent frames (0.7 s). Events were detected using an advanced version of a published protocol69 and detected events were confirmed or rejected according to visual inspection. Diffusion analysis has been performed on INS-1 832/13 data after normalization to lowest values = 0 and maxima (fusion) set to 100. Data were fitted using Origin8 Pro (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA) using the concatenate function for fitting of replicates. Fitted datasets were further compared for statistical difference by F-test in the Origin-Pro package.

Spectroscopy

Monolayer experiments and polarization modulation-infrared reflection-adsorption spectroscopy (PMIRRAS) were performed on a computer-controlled Langmuir film balance (Nima Technology, Coventry, UK) as described previously26. All experiments were performed at room temperature (22 °C). Since bilayer formation is unstable and often results in three layers in PMIRRAS, monolayers are used. The signal derived from the TMDs was isolated by deconvolution as described21, 26.

The morphology of protein/lipid monolayers at the air-water interface was observed by ellipsometry26 using an iElli2000 microscope (NFT, Göttingen, Germany) equipped with a doubled frequency Nd-YAG laser (532 nm, 50 mW), a polarizer, a compensator, an analyzer, and a CCD camera. The lateral resolution of pictures with the x10 magnification lens was about 2 μm. The imaging ellipsometer was used at an incidence angle close to the Brewster angle (54.58°). It operates on the principle of classical null ellipsometry70. All experiments were performed at room temperature. Image patterning was determined by fractal analysis using the Fraclac plugin of ImageJ with 12 grid positions71. Fractal dimensions given here were obtained by box counting and the values indicated (DB) describe the slope of the relationship ln N/ln ε where N are changes in image details and ε the scale, thus indicating how a pattern’s detail changes with the scale at which it is considered.

To obtain structural models, a structure deposited in the PDB (code 2KOG) was used and mutations were performed using the “mutated residue” facility in the Visual Molecular Dynamics software VMD1.8.6.

Statistical Analysis and Data Fitting

Data were expressed as the means ± SEM. Differences between two groups were assessed by a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test or by a one-way ANOVA using XLSTAT software followed by post-hoc tests as indicated in the legends. The null hypothesis was rejected at the level of p < 0.05.

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by ANR grant Exodynamics to R.O., J.L. and B.D., ANR13-PRTS-0017-06 and MESR grant to J.L. Part of the study was supported by a Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator Award (P.R.).

Author Contributions

J.L., R.O., B.D., P.R. and B.H. designed the study; J.L., R.O., B.D., and P.R. secured funding; B.H., P.A.S., A.M., Z.F.B., B.D., M.L., S.C., R.O. and J.L. performed experiments; B.H., P.A.S., J.R., R.M., B.D., S.C., D.P., P.R., R.O. and J.L. analysed data; J.L., P.R. and B.H. wrote the manuscript, all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Patrik Rorsman, Reiko Oda and Jochen Lang contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-03013-3

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rothman JE. The principle of membrane fusion in the cell (Nobel lecture) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2014;53:12676–12694. doi: 10.1002/anie.201402380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jahn R, Fasshauer D. Molecular machines governing exocytosis of synaptic vesicles. Nature. 2012;490:201–207. doi: 10.1038/nature11320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chernomordik LV, Kozlov MM. Mechanics of membrane fusion. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:675–683. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hernandez JM, Kreutzberger AJ, Kiessling V, Tamm LK, Jahn R. Variable cooperativity in SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. Proc. Nat’l Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:12037–12042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407435111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kozlov MM, Chernomordik LV. Membrane tension and membrane fusion. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2015;33:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2015.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen L, Lau MS, Banfield DK. Multiple ER-Golgi SNARE transmembrane domains are dispensable for trafficking but required for SNARE recycling. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2016;27:2633–2641. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E16-05-0277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pieren M, Desfougeres Y, Michaillat L, Schmidt A, Mayer A. Vacuolar SNARE protein transmembrane domains serve as nonspecific membrane anchors with unequal roles in lipid mixing. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:12821–12832. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.647776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Regazzi R, et al. Mutational analysis of VAMP domains implicated in Ca2+-induced insulin exocytosis. EMBO J. 1996;15:6951–6959. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu H, Zick M, Wickner WT, Jun Y. A lipid-anchored SNARE supports membrane fusion. Proc. Nat’l Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:17325–17330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113888108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dhara M, et al. v-SNARE transmembrane domains function as catalysts for vesicle fusion. eLife. 2016;5:e17571. doi: 10.7554/eLife.17571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fdez E, Martinez-Salvador M, Beard M, Woodman P, Hilfiker S. Transmembrane-domain determinants for SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. J. Cell Sci. 2010;123:2473–2480. doi: 10.1242/jcs.061325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou P, Bacaj T, Yang X, Pang ZP, Sudhof TC. Lipid-anchored SNAREs lacking transmembrane regions fully support membrane fusion during neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 2013;80:470–483. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hofmann MW, et al. Self-interaction of a SNARE transmembrane domain promotes the hemifusion-to-fusion transition. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;364:1048–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.09.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hofmann MW, et al. De novo design of conformationally flexible transmembrane peptides driving membrane fusion. Proc. Nat’l Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:14776–14781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405175101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langosch D, et al. Peptide mimics of SNARE transmembrane segments drive membrane fusion depending on their conformational plasticity. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;311:709–721. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neumann S, Langosch D. Conserved conformational dynamics of membrane fusion protein transmembrane domains and flanking regions indicated by sequence statistics. Proteins. 2011;79:2418–2427. doi: 10.1002/prot.23063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giraudo CG, et al. SNAREs can promote complete fusion and hemifusion as alternative outcomes. J. Cell Biol. 2005;170:249–260. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200501093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grote E, Baba M, Ohsumi Y, Novick PJ. Geranylgeranylated SNAREs are dominant inhibitors of membrane fusion. J. Cell Biol. 2000;151:453–466. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.2.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McNew JA, et al. Close is not enough: SNARE-dependent membrane fusion requires an active mechanism that transduces force to membrane anchors. J. Cell Biol. 2000;150:105–117. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.1.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi L, et al. SNARE proteins: one to fuse and three to keep the nascent fusion pore open. Science. 2012;335:1355–1359. doi: 10.1126/science.1214984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yassine W, et al. Reversible transition between α-helix and β-sheet conformation of a transmembrane domain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1788:1722–1730. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ji H, et al. Protein determinants of SNARE-mediated lipid mixing. Biophys. J. 2010;99:553–560. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.04.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu Z, et al. Dilation of fusion pores by crowding of SNARE proteins. eLife. 2017;6:e22964. doi: 10.7554/eLife.22964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ngatchou AN, et al. Role of the synaptobrevin C terminus in fusion pore formation. Proc. Nat’l Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:18463–18468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006727107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tong J, Borbat PP, Freed JH, Shin YK. A scissors mechanism for stimulation of SNARE-mediated lipid mixing by cholesterol. Proc. Nat’l Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:5141–5146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813138106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yassine W, et al. Effect of monolayer lipid charges on the structure and orientation of protein VAMP1 at the air-water interface. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1798:928–937. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collins SC, et al. Increased expression of the diabetes gene SOX4 reduces insulin secretion by impaired fusion pore expansion. Diabetes. 2016;65:1952–1961. doi: 10.2337/db15-1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blanchard AE, Arcario MJ, Schulten K, Tajkhorshid E. A highly tilted membrane configuration for the prefusion state of synaptobrevin. Biophys. J. 2014;107:2112–2121. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bowen M, Brunger AT. Conformation of the synaptobrevin transmembrane domain. Proc. Nat’l Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:8378–8383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602644103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Betts, M. J. & Russell, R. B. Chapter 13. Amino-Acid Properties and Consequences of Substitutions; In Bioinformatics for Geneticists (eds M.R. Barnes & I.C. Gray; John Wiley & Sons) doi:10.1002/0470867302.ch14 (2003).

- 31.Xu Y, Zhang F, Su Z, McNew JA, Shin YK. Hemifusion in SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:417–422. doi: 10.1038/nsmb921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mendelsohn R, Mao G, Flach CR. Infrared reflection-absorption spectroscopy: principles and applications to lipid-protein interaction in Langmuir films. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1798:788–800. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han J, Pluhackova K, Bruns D, Bockmann RA. Synaptobrevin transmembrane domain determines the structure and dynamics of the SNARE motif and the linker region. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1858:855–865. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2016.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laage R, Langosch D. Dimerization of the synaptic vesicle protein synaptobrevin (vesicle-associated membrane protein) II depends on specific residues within the transmembrane segment. Eur. J. Biochem. 1997;249:540–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barg S, et al. Delay between fusion pore opening and peptide release from large dense-core vesicles in neuroendocrine cells. Neuron. 2002;33:287–299. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00563-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hohmeier HE, et al. Isolation of INS-1-derived cell lines with robust ATP-sensitive K+ channel-dependent and -independent glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2000;49:424–430. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.3.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borisovska M, et al. v-SNAREs control exocytosis of vesicles from priming to fusion. EMBO J. 2005;24:2114–2126. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Papini E, Rossetto O, Cutler DF. Vesicle-associated membrane protein (VAMP)/synaptobrevin-2 is associated with dense core secretory granules in PC12 neuroendocrine cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:1332–1336. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.3.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Regazzi R, et al. VAMP-2 and cellubrevin are expressed in pancreatic beta-cells and are essential for Ca2+-but not for GTPγS-induced insulin secretion. EMBO J. 1995;14:2723–2730. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07273.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zenisek D, Perrais D. Imaging Exocytosis with Total Internal Reflection Microscopy (TIRFM) CSH Protoc. 2007 doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot4863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miesenbock G, De Angelis DA, Rothman JE. Visualizing secretion and synaptic transmission with pH-sensitive green fluorescent proteins. Nature. 1998;394:192–195. doi: 10.1038/28190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Braun M, et al. Corelease and differential exit via the fusion pore of GABA, serotonin, and ATP from LDCV in rat pancreatic beta cells. J. Gen. Physiol. 2007;129:221–231. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Galvanovskis J, Braun M, Rorsman P. Exocytosis from pancreatic beta-cells: mathematical modelling of the exit of low-molecular-weight granule content. Interface Focus. 2011;1:143–152. doi: 10.1098/rsfs.2010.0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang CW, et al. A structural role for the synaptobrevin 2 transmembrane domain in dense-core vesicle fusion pores. J. Neurosci. 2015;35:5772–5780. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3983-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rajappa R, Gauthier-Kemper A, Boning D, Huve J, Klingauf J. Synaptophysin 1 clears synaptobrevin 2 from the presynaptic active zone to prevent short-term depression. Cell Rep. 2016;14:1369–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Veit M, Becher A, Ahnert-Hilger G. Synaptobrevin 2 is palmitoylated in synaptic vesicles prepared from adult, but not from embryonic brain. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2000;15:408–416. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koehler Leman J, Ulmschneider MB, Gray JJ. Computational modeling of membrane proteins. Proteins. 2015;83:1–24. doi: 10.1002/prot.24703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Williams D, Vicôgne J, Zaitseva I, McLaughlin S, Pessin JE. Evidence that electrostatic interactions between vesicle-associated membrane protein 2 and acidic phospholipids may modulate the fusion of transport vesicles with the plasma membrane. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009;20:4910–4919. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-04-0284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stein A, Weber G, Wahl MC, Jahn R. Helical extension of the neuronal SNARE complex into the membrane. Nature. 2009;460:525–528. doi: 10.1038/nature08156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stratton BS, et al. Cholesterol increases the openness of SNARE-mediated flickering fusion pores. Biophys. J. 2016;110:1538–1550. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lindau M, Hall BA, Chetwynd A, Beckstein O, Sansom MS. Coarse-grain simulations reveal movement of the synaptobrevin C-terminus in response to piconewton forces. Biophys. J. 2012;103:959–969. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shen XM, et al. Novel synaptobrevin-1 mutation causes fatal congenital myasthenic syndrome. Ann. Clin. Translat. Neurol. 2017;4:130–138. doi: 10.1002/acn3.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fang Q, Lindau M. How could SNARE proteins open a fusion pore? Physiology (Bethesda) 2014;29:278–285. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00026.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao WD, et al. Hemi-fused structure mediates and controls fusion and fission in live cells. Nature. 2016;534:548–552. doi: 10.1038/nature18598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sharma S, Lindau M. The mystery of the fusion pore. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016;23:5–6. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chan YH, van Lengerich B, Boxer SG. Effects of linker sequences on vesicle fusion mediated by lipid-anchored DNA oligonucleotides. Proc. Nat’l Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:979–984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812356106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chanturiya A, Chernomordik LV, Zimmerberg J. Flickering fusion pores comparable with initial exocytotic pores occur in protein-free phospholipid bilayers. Proc. Nat’l Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:14423–14428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bao H, et al. Exocytotic fusion pores are composed of both lipids and proteins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016;23:67–73. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tse FW, Iwata A, Almers W. Membrane flux through the pore formed by a fusogenic viral envelope protein during cell fusion. J. Cell Biol. 1993;121:543–552. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.3.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fan HP, Fan FJ, Bao L, Pei G. SNAP-25/syntaxin 1A complex functionally modulates neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid reuptake. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:28174–28184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601382200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Garnier J, Gibrat J-F, Robson B. GOR secondary structure prediction method version IV. Meth. Enzymol. 1996;266:540–553. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(96)66034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Boal F, Laguerre M, Milochau A, Lang J, Scotti PA. A charged prominence in the linker domain of the cysteine-string protein Cspα mediates its regulated interaction with the calcium sensor synaptotagmin 9 during exocytosis. FASEB J. 2011;25:132–143. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-152033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Raoux M, et al. Multilevel control of glucose homeostasis by adenylyl cyclase 8. Diabetologia. 2015;58:749–757. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3445-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roger B, et al. Adenylyl cyclase 8 is central to glucagon-like peptide 1 signalling and effects of chronically elevated glucose in rat and human pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia. 2011;54:390–402. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1955-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kloepper TH, Kienle CN, Fasshauer D. SNAREing the basis of multicellularity: consequences of protein family expansion during evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2008;25:2055–2068. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gillis, K. D. In Single-Channel Recording (eds Bert Sakmann & Erwin Neher) 155–198 (Springer US, 2nd ed.) doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-1229-9_7 (1995)

- 67.Chandra V, et al. RFX6 Regulates insulin secretion by modulating Ca2+ homeostasis in human beta cells. Cell Rep. 2014;9:2206–2218. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Meth. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Perrais D, Kleppe IC, Taraska JW, Almers W. Recapture after exocytosis causes differential retention of protein in granules of bovine chromaffin cells. J. Physiol. 2004;560:413–428. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.064410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Azzam, R. M. A. & Bashara, N. M. Ellipsometry and polarized light. (North-Holland Publishing Co, Amsterdam, New York, 1977).

- 71.Karperien, A. FracLac for ImageJ. http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/plugins/fraclac/FLHelp/Introduction.htm (1999–2013).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.