Abstract

We evaluated differences in the compositions of faecal microbiota between 52 end stage renal disease (ESRD) patients and 60 healthy controls in southern China using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and high-throughput sequencing (16S ribosomal RNA V4-6 region) methods. The absolute quantification of total bacteria was significantly reduced in ESRD patients (p < 0.01). In three enterotypes, Prevotella was enriched in the healthy group whereas Bacteroides were prevalent in the ESRD group (LDA score > 4.5). 11 bacterial taxa were significantly overrepresented in samples from ESRD and 22 bacterial taxa were overrepresented in samples from healthy controls. The butyrate producing bacteria, Roseburia, Faecalibacterium, Clostridium, Coprococcus and Prevotella were reduced in the ESRD group (LDA values > 2.0). Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) indicated that Cystatin C (CysC), creatinine and eGFR appeared to be the most important environmental parameters to influence the overall microbial communities. In qPCR analysis, The butyrate producing species Roseburia spp., Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Prevotella and Universal bacteria, were negatively related to CRP and CysC. Total bacteria in faeces were reduced in patients with ESRD compared to that in healthy individuals. The enterotypes change from Prevotella to Bacteroides in ESRD patients. The gut microbiota was associated with the inflammatory state and renal function of chronic kidney disease.

Introduction

The human gut is immensely populated with microorganisms, predominantly anaerobic bacteria. This internalized ‘Microbial organ’, which are not encoded in the host genome, consists of at least 1013 citizens and 500–1,000 different species whose collective genomes are estimated to contain 100 times more genes than our own human genome1, 2. This microbial community forms a natural defense barrier and influences nutrition (vitamin K and vitamin B12 synthesis, Energy regulation)3, 4, physiology5, immune function (mucosal immune responses, inflammatory signaling through toll-like receptors, NF-κB, etc; and adaptive Immunity through CD4 T-regulatory cell populations (Tregs))6, 7, and metabolism (short-chain fatty acids, bile acids, choline, indole, lipids and others)3, 4, 8. Various clinical and animal studies suggest that our gut microbial environment plays a critical role in both maintenance of health and disease pathogenesis, such as in obesity9, diabetes10, 11, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)10, IBD12, cardiovascular disease13, cancers14, and refractory Clostridium difficile infection15.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is widespread, afflicting millions of people worldwide. In China, approximately 119.5 million adults have CKD, making it an important public health problem16, 17. CKD patients have enteric bacterial overgrowth and harbor. A greatly increased microbial flora comprises both anaerobes (107 bacteria/mL) and aerobes (106 bacteria/mL) in the duodenum and jejunum, which is quantitatively comparable to those in blind loop. However the composition of these does not differ significantly between the two groups18. An fecal analysis revealed a disturbed composition of microbiota characterized by an overgrowth of aerobic bacteria in hemodialysis patients19. Recent studies have revealed profound alterations of gut microbiota in patients and animals with CKD. Vaziri et al. demonstrated via 16S rRNA genePhyloChip analysis that uremia profoundly alters intestinal microbial flora20. Moreover some studies have suggested the pathogenic role of gut microbiota in kidney disease21. Alterations in the composition of the microbiome and accumulation of gut derived uremic toxins (such as lipopolysaccharides, indoxyl sulphate (IS), p-cresyl sulphate (PCS), amines, ammonia, and trimethylamine oxide) contribute to the systemic inflammation, cardiovascular disease and numerous other CKD associated complications13, 22, 23. IS and PCS were associated with elevated levels of selected inflammatory markers (serum IL-6, TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma) and an antioxidant in CKD patients24 and predict progression of CKD25. Butyrate produced from microbial fermentation is important for energy metabolism and normal development of colonic epithelial cells, mainly has a protective role in relation to colonic disease, and appears to decrease the inflammatory response26, 27. Smith et al.28 found that short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) regulate the size and function of the colonic Treg pool, which play a major role in the pathogenesis of systemic inflammation, maintaining immunological self-tolerance, limiting the inflammatory response to foreign antigens and protecting against colitis. Butyrate regulates the differentiation of Treg cells29. ESRD is compounded by the depletion and dysfunction of regulatory T lymphocytes30. CKD impairs the barrier function and alters microbial flora of the intestine. Bacterial translocation and uremic toxicity as possible sources contributed to the chronic inflammation noted in uremia31, 32. The aim of this study was to evaluate and quantify differences in the composition of gut microbiota in ESRD patients in southern China.

Materials and Methods

Study subjects

CKD definitions and classifications in this study are in accordance with the 2002 clinical practice guideline, end stage renal disease (ESRD) was defined as the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) less than 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 for 3 months, irrespective of the presence or absence of kidney damage33. All ESRD patients were diagnosed in accordance with this guideline by professional kidney internal medicine physicians33. All methods, including the collection of blood and faecal samples, were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. All the people have signed the informed consent. The study was reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China. Fresh faecal samples collected in sterile containers from 52 ESRD patients and 60 healthy volunteers (controls) were used for quantitative PCR (qPCR), of these, samples from 27 ESRD patients and 26 healthy volunteers underwent Pyrosequencing. The underlying cause of 21 ESRD patients was chronic glomerulonephritis, 11 was hypertensive nephropathy, 6 was obstructive nephropathy, 3 was polycystic kidney disease, 2 was systemic lupus erythematosus, 2 was chronic pyelonephritis, 7 was unclear. Only two of the ESRD patients have received hemodialysis therapy through deep venous catheterization for once before the enrollment because of the acute hyperkalemia. The rest patients have never been treated with dialysis. All ESRD inpatients had never been treated with dialysis or without a regular dialysis. Exclusion criteria included treatment with antibiotics, probiotics/prebiotics and other laxatives in the 4 weeks preceding sample collection. We also excluded cholecystectomy, colectomy or intestinal disease and diabetes and hyperlipidemia from our data. Clinical datas of all the subjects were shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical parameters among ESRD patients and healthy controls.

| characteristics | ESRD (n = 52) | controls (n = 60) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 51.58 ± 18.33 | 52.53 ± 13.98 | 0.746 |

| sex, male (female) | 29 (23) | 25 (35) | 0.184 |

| BMI (kg/m^2) | 22.52 ± 2.74 | 21.64 ± 3.25 | 0.098 |

| CysC (mg/L) | 6.74 ± 3.84 | 0.91 ± 0.14 | 0.000** |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 26.65 ± 10.38 | 5.24 ± 1.54 | 0.000** |

| Scr (μmol/L) | 654.36 ± 174.86 | 76.57 ± 26.89 | 0.000** |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 6.86 ± 2.87 | 98.03 ± 27.32 | 0.000** |

| CRP (mg/L) | 19.20 ± 40.64 | 1.93 ± 2.58 | 0.005** |

| LPS (EU/mL) | 0.11 ± 0.05 | 0.08 ± 0.04 | 0.033* |

| glucose (mmol/L) | 5.45 ± 1.46 | 4.78 ± 0.60 | 0.089 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.71 ± 1.31 | 1.61 ± 1.21 | 0.669 |

| CHOL (mmol/L) | 4.80 ± 1.49 | 4.61 ± 0.69 | 0.831 |

| VLDL (mmol/L) | 0.79 ± 0.51 | 0.61 ± 0.0.45 | 0.134 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 2.63 ± 1.15 | 2.76 ± 0.59 | 0.749 |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 1.38 ± 0.41 | 1.54 ± 0.41 | 0.194 |

| Lpa (mg/L) | 0.44 ± 0.29 | 0.39 ± 0.21 | 0.066 |

| ApoE (mg/L) | 43.17 ± 20.27 | 39.67 ± 27.00 | 0.697 |

| ApoA, B (mg/L) | 1.33 ± 0.32 | 1.45 ± 0.43 | 0.146 |

In this experiment, patients with diabetes and hyperlipidemia were excluded. Abbrevitions: CKD, Chronic kidney disease; BMI, body mass index; Scr, serum creatinine; CysC, Cystatin C; BUN, Blood Urea Nitrogen; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate. CRP, C-reactive protein; LPS, Lipopolysaccharide; TG, Triglyceride; CHOL, Cholesterol; VLDL, very low-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HDL, high density lipoprotein; Lpa, lipoproteins a; ApoE, apolipoprotein E; ApoA, B, apolipoprotein A, B *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. mean ± SD.

Assessment of clinical parameters

Fasting venous blood samples were collected in the morning, and centrifuged at 3000 g/min, at 4 °C for 10 min. The recovered supernatants was separated in 200 μL tubes and immediately frozen at −80 °C. We used the enzymatic method (isotope dilution mass spectrometry, IDMS reference method) to measure the creatinine. A modified kinetic Jaffé method was used to measure blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation was used to measure estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) values. Cystatin C (CysC) and C-reactive protein (CRP) were measured by immunoturbidimetric assays. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was detected with the chromogenic end-point Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) assay. Plasma cholesterol (CHOL); triglycerides (TG); and high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) cholesterol levels were determined using enzymatic methods.

Sampling and DNA extraction

Fresh stools were collected one day after enrollment and frozen at −80°C, patients who did not have a bowel movement were excluded. Two tubes were collected and filled at least 1/3. According to the TIANamp Stool DNA Kit (TIANGEN Biotech, Beijing, China) manufacturer steps to extract the faecal DNA. All DNA samples were stored at −80 °C until further processing.

Pyrosequencing and bioinformatics analysis

Isolated fecal DNA was used as a template for amplification of the 16S rRNA V4-6 region using the universal primer V4F (5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′) and V6R (5′-ACAGCCATGCNCACCT-3′). 20 μl reaction mixture: 10 μl TaKaRa Premix Taq, 2 μl template DNA, 0.5 μl 10 μM barcode forward primer, 0.5 μl 10 μM reverse primer, and 7 μl double-distilled H2O. The PCR cycle conditions: an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, 25 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 59 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s, and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. PCR products were sequenced using Illumina GAII (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) at the Beijing Genomic Institute (Shenzhen, China). Sequencing results were clustered by lllumina paired barcoded - sequencing (end) (BIPES) (PE) process for preliminary analysis, the rest of the sequence were screened by UCHIME and removed the suspected chimeric sequence. All reads were sorted into different samples according to their barcodes. Then the two stage clustering (TSC) was used for clustering to extract the OUT in order to to distinguish the high abundance and low abundance sequences. Principal coordinates analysis (PcoA) based on UniFrac distance was performed with QIIME. The linear discriminant analysis (LDA) with effect size measurements (LEfSe) were used to identify indicator bacterial groups specialized within the two groups.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

The bacteria selected for qPCR are wellknown bacteria in gut. Escherichia coli (E. coli) belongs to Proteobacteria. Bacteroides fragilis group belong to Bacteroidetes. Bifidobacterium belong to Actinobacteria. Enterococcus spp., Lactobacillus group and Clostridium coccoides group belong to Firmicutes. Based on the sequencing data, Roseburia spp., Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Prevotella which are typical butyrate producing bacteria were decreased in ESRD patients, so we chose it. All qPCR primer are listed in Table 2 34–38. qPCR assays were performed in a 96-well optical plate on a LightCycler® 480 Real-Time PCR System (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). All assays were carried out in duplicate. The reaction mixtures consisted of 10 μl TaKaRa Premix Taq, 2 μl template DNA, 0.4 μl 10 μM barcode forward primer, 0.4 μl 10 μM reverse primer, and 7.2 μl double-distilled H2O. The copy number of target DNA was determined by serially diluting standards (101 to 107 copies of plasmid DNA containing the respective amplicon for each set of primers) running on the same plate. Bacterial quantity was expressed as log10 bacteria per gram of stool.

Table 2.

Primers used for qPCR in this study.

| Target Bacteria | Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Annealing (°C) | Product | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Universal bacteria | Univ-F | AGAGTTTGATCATGGCTCAG | 55 | 540 | 34 |

| Univ-R | ACCGCGACTGCTGCTGGCAC | ||||

| E. coli | E. col-F | GTTAATACCTTTGCTCATTGA | 55 | 340 | 35 |

| E. col-R | ACCAGGGTATCTAATCC | ||||

| Bacteroides fragilis group | Bfra-F | ATAGCCTTTCGAAAGRAAGAT | 50 | 501 | 36 |

| Bfra-R | CCAGTATCAACTGCAATTTTA | ||||

| Enterococcus spp. | Ente-F | CCCTTATTGTTAGTTGCCATCATT | 61 | 144 | 37 |

| Ente-R | ACTCGTTGTACTTCCCATTGT | ||||

| Lactobacillus group | Lact-f | AGCAGTAGGGAATCTTCCA | 58 | 341 | 37 |

| Lact-R | CACCGCTACACATGGAG | ||||

| Bifidobacterium | Bifid-F | CTCCTGGAAACGGGTGG | 55 | 549–563 | 36 |

| Bifid-R | GGTGTTCTTCCCGATATCTACA | ||||

| Clostridium coccoides group | Ccoc-F | AAATGACGGTACCTGACTAA | 50 | 438–441 | 36 |

| Ccoc-R | CTTTGAGTTTCATTCTTGCGAA | ||||

| Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | Fae-F | GGAGGAAGAAGGTCTTCGG | 60 | 248 | 38 |

| Fae-R | AATTCCGCCTACCTCTGCACT | ||||

| Roseburia spp. | Ros-F | GCGGTRCGGCAAGTCTGA | 60 | 81 | 38 |

| Ros-R | CCTCCGACACTCTAGTMCGAC | ||||

| Prevotella | Pre-F | GAAGGTCCCCCACATTG | 103 | 60 | 38 |

| Pre-R | CGCKACTTGGCTGGTTCAG |

Statistical analysis

Enumeration data are tested by chi-square. Independent-samples T test was used to analyse the quantitative data. Spearman rank correlation were calculated to estimate the linear correlations between variables. Wilcox test, Kruskal-Wallis, PcoA, LEfSe, Monte Carlo test CCA were used to analyse the sequcing datas. Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) was performed to measure physiological properties that have the most significant influence on microbial communities. Statistical analyses were performed with the statistical software package SPSS13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P < 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

Results

Patients and controls

CysC, BUN, and creatinine was significantly higher, and eGFR was reduced in ESRD patients compared to healthy controls. Levels of the plasma inflammatory biomarker CRP differed significantly between ESRD patients and controls (p = 0.005). LPS was increased in ESRD patients (p = 0.033). The ethic background of all the participants were Han nationally Chinese. All the ESRD patients had been treated with phosphate binders, oral iron supplements or intravenous iron compounds, antihypertensive drugs. 12 of the ESRD patients had been treated with calcium supplements and Vitamin D. There were no significant differences in age, sex, body mass index (BMI), glucose, TG, CHOL, VLDL, LDL, HDL, Lpa, Lipoprotein a (Lpa), apolipoprotein E (ApoE), and apolipoprotein A, B (ApoA, B) (Table 1).

Diversity and phylum/subfamily -level taxonomic distribution of gut microbiota in ESRD patients

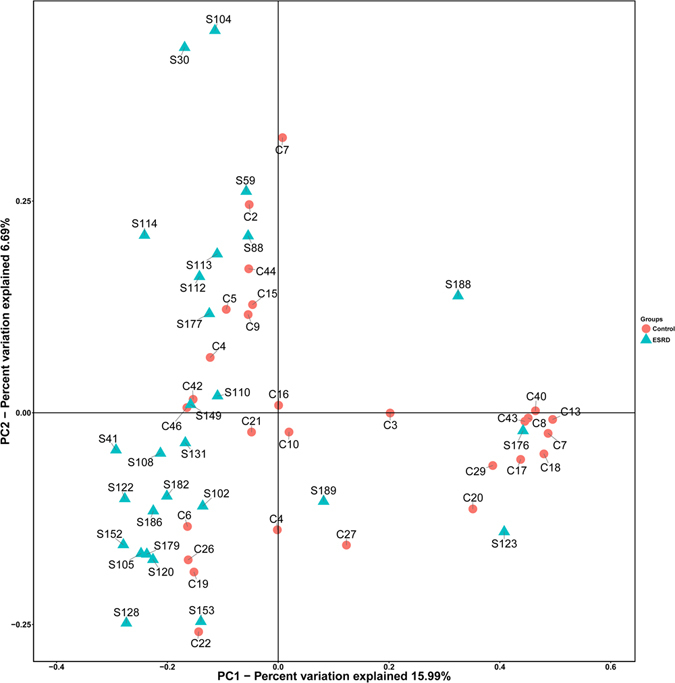

Diversity concerns both taxon richness and evenness, and our results demonstrated that the diversity was similar (p > 0.05) as assessed by chao1, observed_species, Shannon, simpson diversity indexs. PCoA based on the UniFrac metric did not reveal a separation trend of healthy controls and ESRD patients (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Principle Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) of gut microbiota from ESRD (Green) and healthy control (Red). The first two axes of the principal coordinate analysis are represented with principal coordinate axis 1 (15.99% variability) and principal coordinate axis 2 (6.69% variability).

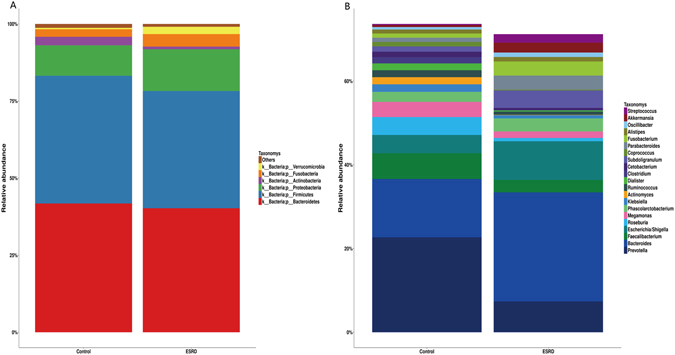

Bacteroidetes was the most abundant phylum in both healthy individuals and CKD patients, accounting for 41.76%, 40.23% of the total valid reads respectively. Firmicutes was the second most abundant phylum in all samples with an average relative abundance of 41.43%, 38.01% respectively. The other dominant phyla were Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Fusobacteria, Verrucomicrobia and Others (Fig. 2A). Based on the average relative abundance, 21 genera were dominant (>=1%) at the genus level. Bacteroides, Escherichia/Shigella, Subdoligranulum, Fusobacterium. etc were enriched in ESRD patients. Prevotella, Roseburia, Faecalibacterium, Megamonas. etc were more abundant in controls (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Relative abundance of the gut microbiota in this study. Microbiome composition in human from controls (n = 26) or patients with ESRD (n = 27). The composition is based on 16S rRNA sequecing. Results are shown at the (A) phylum and (B) genus level. The figure shows species median relative abundance >= 1% of total abundance in either the healthy control group or the ESRD group, and value < 1%, unclassified, unidentified are classified as Others.

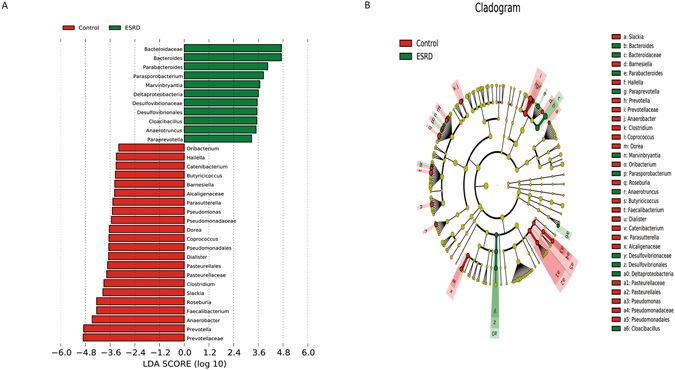

A reduction in SCFAs producing bacteria as a prominent feature of ESRD patients

LEfSe showed so much biomarkers for ESRD patients and controls subiects (Fig. 3) (LDA score > 2.0, p < 0.05). 11 species enriched in ESRD patients, and 22 in controls. According to Wong J39 Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis, Bacteroidaceae with p-Cresol production enzymes enriched in ESRD patients. Desulfovibrionaceae, Bacteroidaceae, Alcaligenaceae, Pseudomonadaceae, and Pasteurellaceae produced urease, Bacteroidaceae’s relative abundance was higher, the others were much lower in ESRD patients than the controls group in this study. Microbes of the genus Prevotella, Roseburia, Faecalibacterium, Clostridium, Coprococcus can produce butyrate26, Dorea was the other predominant SCFA-producing genera40. All of these species were reduced in ESRD patients, indicating that bacteria producing SCFAs especially butyrate were decreased in ESRD patients. Bacteroides (enterotype 1), Prevotella (enterotype 2) and Ruminococcus (enterotype 3) were three main enterotypes of human gut microbiota41. In this study, from healthy people to ESRD patients, the enterotype changes from Prevotella (enterotype 2) to Bacteroides (enterotype 1).

Figure 3.

Indicator microbial groups within the three groups of individuals with logarithmic linear discriminant analysis (LDA) score higher than 2 determined by effect size (LefSe). (A) Histogram of the LDA scores computed for differentially abundant bacterial taxa between healthy controls and patients with ESRD. (B) Cladograms of bacterial lineages with significantly different representation in humans with or without ESRD. Lineages on the bacterial trees are color-coded to indicate whether the taxon does (red or green) or does not (yellow) significantly differ between sample classes. Of those, 11 bacterial taxa were significantly overrepresented in samples from ESRD (green) and 22 bacterial taxa were overrepresented in samples from healthy control (red). Prevotella (red) were significantly overrepresented in control and Bacteroides (green) were overrepresented in ESRD patients. The producing butyrate bacterial taxa (Roseburia, Faecalibacterium, Prevotellaceae, Prevotella, and Coprococcus) was under-abundant in ESRD patients.

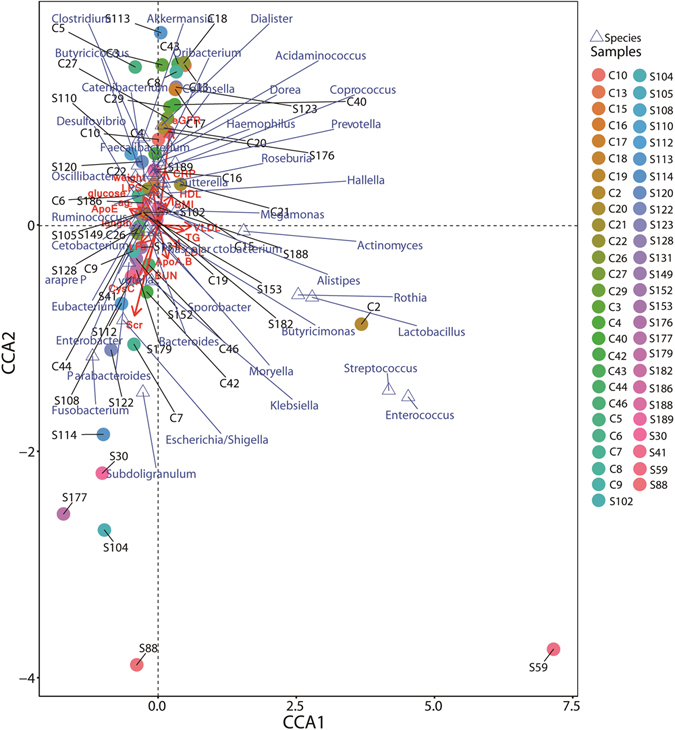

Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA)

Microbial community may be more correlated with indigenous environmental parameters. Analyzing the dynamic changes of microbial communities with geochemical factors will reveal the correlation between environmental parameters and microbial community. Therefore, CCA analysis was used to reveal how microbes can adapt to the changes of physiochemical environments. A correlation between the important environmental parameters and microbial community was discerned by CCA analysis as shown in Fig. 4. Sixteen environmental parameters and the dominant genera (>1%) in each sample were selected to determine their correlation. The length of an environmental parameter arrow indicated the strength of the environmental parameter to the overall microbial communities. As such, CysC (r^2 = 0.1689, p = 0.020), creatinine (r^2 = 0.1593, p = 0.008) and eGFR (r^2 = 0.1255, p = 0.041) concentrations appears to be the most important environmental parameters (Monte Carlo test). For instance, Enterobacter, Bacteroides, Fusobacterium, Escherichia and Klebsiella, which were positively correlated with CysC, creatinine (Scr) as shown in Fig. 4, and dominant in ESRD patients. Whereas Faecalibacterium, Akkermansia, Prevotella, Roseburia, Coprococcus and Clostridium were positively correlated with eGFR, and dominant in controls. Therefore, it is fair to propose that CKD played an active role in shaping the indigenous microbial communities.

Figure 4.

Canonical Correspondence Analysis (CCA) illustrating relations between bacteria taxa and internal environmental parameters accumulated in healthy controls and patients with ESRD in China. Arrows indicate the direction and magnitude of internal environmental parameters associated with bacterial community structure. The explained variance of the principal axes [Axis 1 (horizontally) and Axis 2 (vertically)] are 9.319% and 6.008%, respectively; The species explained 39.82% of the total information amount. The filled circle represents samples, triangle represents species. S* and C* represent ESRD patients and healthy controls respectively.

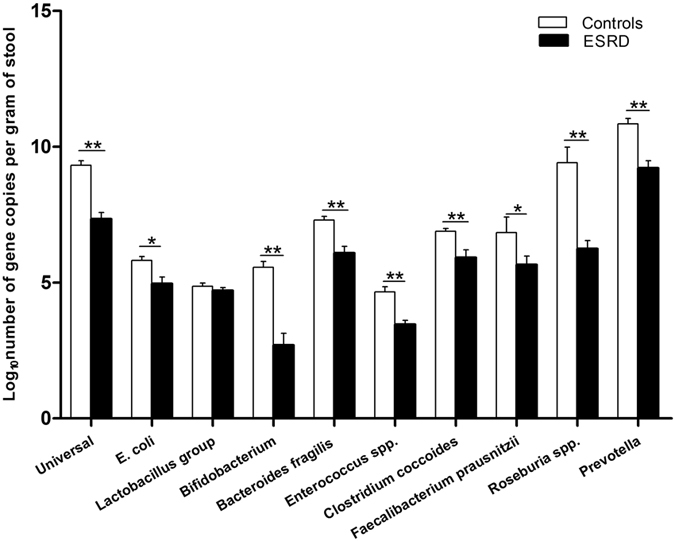

Quantification of well known species in faeces by qPCR

qPCR was used to assess changes in bacterial absolute quantity in faecal samples from the two groups (Fig. 5). Bacterial copy number values were converted into logarithmic values before analysis. Quantities of total gene copies of Universal bacteria, E. coli, Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides fragilis group, Enterococcus spp., Clostridium coccoides group, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia spp. and Prevotella were significantly decreased in ESRD patients compared with controls (p = 0.000, p = 0.001, p = 0.000, p = 0.000, p = 0.000, p = 0.000, p = 0.028, p = 0.000, p = 0.000, respectively). However, the numbers of beneficial microorganisms from the Lactobacillus group were similar between two groups (p = 0.395). In ESRD patients, universal bacteria were decreased, and the butyrate producing species Clostridium coccoides group, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia spp. and Prevotella were also reduced, consistent with the sequencing results.

Figure 5.

Bacterial groups quantified by qPCR expressed as log10 bacteria per gram of stool. qPCR for the common micropopulation in control subjects and ESRD patients. Black and white bars represent ESRD patients and healthy controls respectively. Independent-samples T Test was used to evaluate statistical difference between the two groups. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Butyrate producing gut microbes are negatively related to microinflammation and renal function via qPCR

Among these, the butyrate producing species Roseburia spp., Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Prevotella and Universal bacteria, were negatively related to inflammation index CRP (r = −0.452, p = 0.001; r = −0.431, p = 0.002; r = −0.480, p = 0.000; and r = −0.438, p = 0.000; respectively) (Table 3). In addition, levels of Roseburia spp., Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Clostridium coccoides group, Prevotella and Universal bacteria, were negatively correlated with CysC level sensitive index to evaluate glomerular filtration rate (r = −0.414, p = 0.003; r = −0.395, p = 0.005; r = −0.400, p = 0.001; r = −0.441, p = 0.001 and r = −0.493, p = 0.000; respectively); The Bifidobacterium and Universal bacteria were negatively associated with renal function index BUN and creatinine (r = −0.495, p = 0.000; r = −0.449, p = 0.000 or r = −0.538, p = 0.000; r = −0.519, p = 0.000, respectively). An inverse tendency was observed with regard to eGFR (r = 0.466, p = 0.000 and r = 0.511, p = 0.000). These findings strengthened and further proved the importance and necessity of butyrate producing bacteria in inflammation or renal function of CKD patients. These data further clarified that the structural dynamics of the bacterial community in the intestinal tract played an important role in CKD progression, especially the beneficial species.

Table 3.

Correlation analysis of CRP, CysC, BUN, creatinine, eGFR values and the species count determined by qPCR.

| Roseburia spp. | Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | Clostridium coccoides group | Lactobacillus group | Bifidobacterium | Bacteroides fragillis | E. coli | Enterococcus | prevotella | Universal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRP | r | −0.452** | −0.431** | −0.289** | −0.085 | −0.303** | −0.277* | −0.295 | −0.062 | −0.480** | −0.438** |

| p | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.008 | 0.447 | 0.005 | 0.015 | 0.075 | 0.538 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| CysC | r | −0.414** | −0.395** | −0.400** | −0.325* | −0.295* | −.0240 | −0.116 | 0.040 | −0.441** | −0.493** |

| p | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.014 | 0.021 | 0.075 | 0.377 | 0.759 | 0.001 | 0.000 | |

| BUN | r | −0.237 | 0.083 | −0.106 | −0.018 | −0.495** | −0.257** | −0.228* | −0.237* | −0.011 | −0.538** |

| p | 0.082 | 0.545 | 0.268 | 0.851 | 0.000 | 0.008 | 0.024 | 0.012 | 0.935 | 0.000 | |

| creatinine | r | −0.070 | 0.049 | −0.145 | −0.064 | −0.449** | −0.326** | −0.183 | −0.264** | 0.078 | −0.519** |

| p | 0.609 | 0.724 | 0.172 | 0.524 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.097 | 0.008 | 0.559 | 0.000 | |

| eGFR | r | 0.295* | 0.117 | 0.243** | 0.039 | 0.466** | 0.260** | 0.159 | 0.190* | 0.287* | 0.511** |

| p | 0.027 | 0.391 | 0.009 | 0.679 | 0.000 | 0.006 | 0.115 | 0.042 | 0.027 | 0.000 | |

| LPS | r | −0.392** | −0.298* | −0.179 | −0.263* | −0.153 | −0.068 | −0.166 | −0.035 | −0.198 | −0.127 |

| p | 0.003 | 0.029 | 0.141 | 0.027 | 0.204 | 0.591 | 0.171 | 0.773 | 0.151 | 0.290 | |

| glucose | r | 0.023 | −0.247 | −0.023 | −0.274 | −0.058 | 0.079 | −0.056 | 0.131 | −0.349 | −0.226 |

| p | 0.906 | 0.189 | 0.892 | 0.095 | 0.727 | 0.663 | 0.742 | 0.433 | 0.054 | 0.167 | |

| ApoE | r | −0.152 | −0.300 | −0.237 | −0.252 | −0.219 | −0.327 | −0.260 | 0.077 | −0.074 | −0.328 |

| p | 0.474 | 0.054 | 0.208 | 0.172 | 0.236 | 0.083 | 0.159 | 0.692 | 0.729 | 0.071 | |

| ApoA, B | r | 0.075 | 0.096 | −0.022 | 0.219 | 0.258 | 0.079 | 0.028 | 0.296 | −0.069 | 0.167 |

| p | 0.728 | 0.661 | 0.909 | 0.119 | 0.67 | 0.684 | 0.883 | 0.119 | 0.749 | 0.370 | |

| Lpa | r | 0.123 | −0.243 | −0.078 | 0.115 | −0.038 | 0.125 | 0.149 | 0.066 | −0.253 | −0.162 |

| p | 0.567 | 0.264 | 0.680 | 0.539 | 0.840 | 0.518 | 0.425 | 0.732 | 0.233 | 0.384 | |

| VLDL | r | −0.132 | −0.145 | 0.039 | 0.155 | −0.011 | 0.161 | −0.076 | 0.263 | −0.104 | −0.042 |

| p | 0.389 | 0.338 | 0.788 | 0.259 | 0.935 | 0.245 | 0.576 | 0.052 | 0.495 | 0.754 | |

| LDL | r | 0.119 | 0.056 | 0.235 | −0.014 | 0.049 | 0.137 | 0.062 | −0.062 | 0.018 | 0.187 |

| p | 0.476 | 0.734 | 0.096 | 0.922 | 0.773 | 0.337 | 0.817 | 0.653 | 0.918 | 0.165 | |

| HDL | r | 0.083 | 0.114 | 0.040 | −0.289 | −0.020 | −0.029 | 0.183 | −0.242 | 0.200 | 0.173 |

| p | 0.586 | 0.464 | 0.771 | 0.159 | 0.880 | 0.437 | 0.178 | 0.875 | 0.187 | 0.581 | |

| TG | r | −0.134 | −0.043 | 0.088 | 0.268 | 0.031 | 0.067 | −0.041 | 0.336* | 0.009 | 0.003 |

| p | 0.564 | 0.780 | 0.520 | 0.063 | 0.897 | 0.635 | 0.763 | 0.021 | 0.955 | 0.984 | |

| CHOL | r | 0.078 | 0.006 | 0.202 | −0.020 | 0.029 | 0.105 | 0.042 | −0.042 | 0.073 | 0.239 |

| p | 0.639 | 0.970 | 0.136 | 0.885 | 0.828 | 0.461 | 0.760 | 0.759 | 0.678 | 0.123 |

Abbrevitions: CysC, Cystatin C; BUN, Blood Urea Nitrogen; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate. Spearman rank correlation were used to evaluate statistical importance: r: correlation coefficient. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Discussion

This report represents the first investigation of faecal microbiota diversity and quantity among Chinese CKD patients that employ high-throughput sequencing and qPCR analyses. We supplemented the intestinal bacteria data of CKD patients. In the analysis of sequencing data, we did not find any diversity differences between CKD patients and controls, which suggests that the diversity of the bacterial community was not destroyed critically, it was not like microbe-scarce scenario. Bacteroidetes (~40%), Firmicutes (~40%) and Proteobacteria (~10%) were the predominant phyla in both healthy individuals and CKD patients, consistent with reports from previous studies among cohorts from Western countries, Africa and Asia42–44. Although Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes were the two most abundant phyla constituting the vast majority of gut microbiota in this study, an interesting variation occurred with regards to Bacteroidetes. Through LEfSe analysis, we found that Prevotella was enriched in the healthy group, and Bacteroides in the CKD group. This enterotype conversion proves once again the correlation between the intestinal flora and CKD41.

Distribution of a number of genera could be differentiated between ESRD patients and controls. The SCFAs (propionate, acetate, and butyrate) are a by-product of the fermentation of non-absorbable complex carbohydrates. Firmicutes- Clostridiales- Lachnospiraceae -Dorea producing SCFAs40 were diminished in ESRD patients. Members of Prevotellaceae possess phosphotransbutyrylase and butyrate kinase39, and Prevotella can produce SCFAs45. In this study, both Prevotella and Prevotellaceae were reduced in ESRD patients. The human colonic butyrate (Short-chain fatty acids) producers are Gram-positive firmicutes, but are phylogenetically diverse. Clostridiales cluster the XIVa (Clostridium coccoides) including Ruminococcus, Coprococcus, Eubacterium hallii (E. hallii), Eubacterium rectale/Roseburia spp. and Clostridiales cluster IV (Clostridium leptum) including Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, and Eubacterium spp. are normally the two most abundant groups of human faecal bacteria that produce butyrate26, 46, 47. Roseburia, Coprococcus, and Faecalibacterium belong to Firmicutes-Clostridiales. All of them are typically producing butyrate bacteria and were particularly and significantly more abundant in healthy controls and decreased in ESRD patients and consistent with previous studies39. The qPCR analysis of Roseburia spp. and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii showed a similar trend in ESRD. Butyrate gets involved in the adjustment of body reaction to inflammation29. Systemic inflammation in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) is mediated by activation of the innate immune system48. The presence of persistent inflammation magnifies the risk of poor outcome, and is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD), via mechanisms related to exacerbation of both wasting and vascular calcification processes and self-enhancement of the inflammatory cascade49. High dietary total fiber intake is associated with lower risk of inflammation and mortality in kidney disease50. Interestingly, CRP was increased in ESRD compared with that in controls. Spearman rank correlation analysis demonstrated that the absolute abundance of Roseburia spp., Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Prevotella and Universal bacteria were negatively associated with CRP level and renal function indexes. These data indicate that bacteria producing butyrate as biomarkers may involve in the pathological process of CKD. Recently, Andrade-Oliveira V proved that SCFAs can reduce inflammation in acute kidney injury (AKI), which supports our inferences51.

Reduced quantity of fecal microbiota were found in ESRD patients on qPCR analysis, This means that the absolute quantity of total faecal microbiota was decreased in CKD patients. In general, Universal bacteria, E. coli, Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides fragilis group, Enterococcus spp., Clostridium coccoides group, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia spp. and Prevotella were decreased in ESRD. Bifidobacterium, Roseburia and Clostridium coccoides 45 can produce SCFAs. Bacteroides fragilis and Clostridium spp. can protect against dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-or trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid-induced colitis52, 53. This suggests that CKD status may influence the absolute quantity of the microbiome, which may result from accumulation of uremic toxins, inflammation and malnutrition and needs further investigation. This reduction in beneficial bacteria may play an important role in the pathogenic processes of CKD.

LPS is derived from the cell wall of gram negative bacteria, and the increase of the gamma Proteobacteria is also effective in increasing the LPS level in circulation. The degree of circulating endotoxemia might be related to the severity of systemic inflammation and features of atherosclerosis in peritoneal dialysis (PD) patients54. LPS may accelerate activation of neutrophils and macrophages/monocytes, which further explain the persistent inflammation of ESRD55. Although most CKD patients presented signs of fluid overload that was associated with endotoxaemia, there was no association between endotoxaemia and systemic inflammation, suggesting the endotoxaemia may not be the main determinant of the inflammatory status in CKD patients56. So the correlation between LPS and inflammation is unclear. In this study, LPS was elevated in ESRD patients, but we didn’t find the correlation between LPS and bacterial amounts. To determine the characteristics of gut microbiota based on kidney function, we excluded the influences of body mass index (BMI), blood lipids, and blood glucose. No significant differences in blood lipid and blood glucose levels were found between CKD patients and controls consistent with that reported in previous study by McIntyre, C. W.57. Further research is needed in this area to provide more conclusive evidence while taking into account the relationships of gut flora with human diet, environment and habits.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by “Guangzhou Pilot Project of Clinical and Translational Research Center (early gastrointestinal cancers, No. 7415696196402)”, “Guangdong Provincial Bio-engineering Research Center for Gastroenterology Diseases”, National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (81570480) and The National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (863 Program) (2015AA020701).

Author Contributions

Shuanghong Jiang wrote the main manuscript text, Shuanghong Jiang, Shan Xie, Dan Lv, Pu Wang, Hanchang He, Ting Zhang, Youlian Zhou, and Qianyun Lin collected clinical datas and analysis. Hongwei Zhou, Jianping Jiang, Jing Nie, Fanfan Hou, and Ye Chen further summarized and concluded the whole subject. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Savage DC. Microbial ecology of the gastrointestinal tract. Annual review of microbiology. 1977;31:107–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.31.100177.000543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu J, Gordon JI. Honor thy symbionts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:10452–10459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1734063100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nieuwdorp M, Gilijamse PW, Pai N, Kaplan LM. Role of the Microbiome in Energy Regulation and Metabolism. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1525–1533. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicholson JK, et al. Host-gut microbiota metabolic interactions. Science. 2012;336:1262–1267. doi: 10.1126/science.1223813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Hara AM, Shanahan F. The gut flora as a forgotten organ. EMBO reports. 2006;7:688–693. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neish AS. Microbes in gastrointestinal health and disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:65–80. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chow J, Lee SM, Shen Y, Khosravi A, Mazmanian SK. Host-bacterial symbiosis in health and disease. Advances in immunology. 2010;107:243–274. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381300-8.00008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodman AL, Gordon JI. Our unindicted coconspirators: human metabolism from a microbial perspective. Cell metabolism. 2010;12:111–116. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bajzer M, Seeley RJ. Physiology: obesity and gut flora. Nature. 2006;444:1009–1010. doi: 10.1038/4441009a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henao-Mejia J, et al. Inflammasome-mediated dysbiosis regulates progression of NAFLD and obesity. Nature. 2012;482:179–185. doi: 10.1038/nature10809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Musso G, Gambino R, Cassader M. Obesity, diabetes, and gut microbiota: the hygiene hypothesis expanded? Diabetes care. 2010;33:2277–2284. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rehman A, et al. Geographical patterns of the standing and active human gut microbiome in health and IBD. Gut. 2015 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Z, et al. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2011;472:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nature09922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garrett WS. Cancer and the microbiota. Science. 2015;348:80–86. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Nood E, et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;368:407–415. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nugent RA, Fathima SF, Feigl AB, Chyung D. The burden of chronic kidney disease on developing nations: a 21st century challenge in global health. Nephron. Clinical practice. 2011;118:c269–277. doi: 10.1159/000321382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang L, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in China: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2012;379:815–822. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simenhoff ML, et al. Bacterial populations of the small intestine in uremia. Nephron. 1978;22:63–68. doi: 10.1159/000181424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hida M, et al. Inhibition of the accumulation of uremic toxins in the blood and their precursors in the feces after oral administration of Lebenin, a lactic acid bacteria preparation, to uremic patients undergoing hemodialysis. Nephron. 1996;74:349–355. doi: 10.1159/000189334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaziri ND, et al. Chronic kidney disease alters intestinal microbial flora. Kidney international. 2013;83:308–315. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anders HJ, Andersen K, Stecher B. The intestinal microbiota, a leaky gut, and abnormal immunity in kidney disease. Kidney international. 2013;83:1010–1016. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mafra D, et al. Role of altered intestinal microbiota in systemic inflammation and cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease. Future microbiology. 2014;9:399–410. doi: 10.2217/fmb.13.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sabatino A, et al. Alterations of intestinal barrier and microbiota in chronic kidney disease. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation: official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2015;30:924–933. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rossi M, et al. Protein-bound uremic toxins, inflammation and oxidative stress: a cross-sectional study in stage 3–4 chronic kidney disease. Archives of medical research. 2014;45:309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu IW, et al. p-Cresyl sulphate and indoxyl sulphate predict progression of chronic kidney disease. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation: official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2011;26:938–947. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pryde SE, Duncan SH, Hold GL, Stewart CS, Flint HJ. The microbiology of butyrate formation in the human colon. FEMS microbiology letters. 2002;217:133–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rose DJ, DeMeo MT, Keshavarzian A, Hamaker BR. Influence of dietary fiber on inflammatory bowel disease and colon cancer: importance of fermentation pattern. Nutrition reviews. 2007;65:51–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.tb00282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith PM, et al. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science. 2013;341:569–573. doi: 10.1126/science.1241165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Furusawa Y, et al. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature. 2013;504:446–450. doi: 10.1038/nature12721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hendrikx TK, et al. End-stage renal failure and regulatory activities of CD4+CD25bright+FoxP3+ T-cells. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation: official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2009;24:1969–1978. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vaziri ND. CKD impairs barrier function and alters microbial flora of the intestine: a major link to inflammation and uremic toxicity. Current opinion in nephrology and hypertension. 2012;21:587–592. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e328358c8d5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kotanko P, Carter M, Levin NW. Intestinal bacterial microflora–a potential source of chronic inflammation in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation: official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2006;21:2057–2060. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. American journal of kidney diseases: the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation39, S1–266 (2002). [PubMed]

- 34.Guarner C, et al. The detection of bacterial DNA in blood of rats with CCl4-induced cirrhosis with ascites represents episodes of bacterial translocation. Hepatology. 2006;44:633–639. doi: 10.1002/hep.21286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malinen E, Kassinen A, Rinttila T, Palva A. Comparison of real-time PCR with SYBR Green I or 5′-nuclease assays and dot-blot hybridization with rDNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes in quantification of selected faecal bacteria. Microbiology. 2003;149:269–277. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.25975-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsuki T, et al. Development of 16S rRNA-gene-targeted group-specific primers for the detection and identification of predominant bacteria in human feces. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2002;68:5445–5451. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.11.5445-5451.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rinttila T, Kassinen A, Malinen E, Krogius L, Palva A. Development of an extensive set of 16S rDNA-targeted primers for quantification of pathogenic and indigenous bacteria in faecal samples by real-time PCR. Journal of applied microbiology. 2004;97:1166–1177. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hedin CR, et al. Altered intestinal microbiota and blood T cell phenotype are shared by patients with Crohn’s disease and their unaffected siblings. Gut. 2014;63:1578–1586. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong J, et al. Expansion of urease- and uricase-containing, indole- and p-cresol-forming and contraction of short-chain fatty acid-producing intestinal microbiota in ESRD. American journal of nephrology. 2014;39:230–237. doi: 10.1159/000360010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang J, et al. A phylo-functional core of gut microbiota in healthy young Chinese cohorts across lifestyles, geography and ethnicities. The ISME journal. 2015;9:1979–1990. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arumugam M, et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2011;473:174–180. doi: 10.1038/nature09944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature486, 207–214, doi:10.1038/nature11234 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.De Filippo C, et al. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:14691–14696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005963107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nam YD, Jung MJ, Roh SW, Kim MS, Bae JW. Comparative analysis of Korean human gut microbiota by barcoded pyrosequencing. PloS one. 2011;6:e22109. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Macfarlane GT, Macfarlane S. Bacteria, colonic fermentation, and gastrointestinal health. Journal of AOAC International. 2012;95:50–60. doi: 10.5740/jaoacint.SGE_Macfarlane. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kumari R, Ahuja V, Paul J. Fluctuations in butyrate-producing bacteria in ulcerative colitis patients of North India. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG. 2013;19:3404–3414. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i22.3404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Louis P, Flint HJ. Diversity, metabolism and microbial ecology of butyrate-producing bacteria from the human large intestine. FEMS microbiology letters. 2009;294:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vaziri ND, Pahl MV, Crum A, Norris K. Effect of uremia on structure and function of immune system. Journal of renal nutrition: the official journal of the Council on Renal Nutrition of the National Kidney Foundation. 2012;22:149–156. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2011.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carrero JJ, Stenvinkel P. Persistent inflammation as a catalyst for other risk factors in chronic kidney disease: a hypothesis proposal. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2009;4(Suppl 1):S49–55. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02720409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krishnamurthy VM, et al. High dietary fiber intake is associated with decreased inflammation and all-cause mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney international. 2012;81:300–306. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Andrade-Oliveira V, et al. Gut Bacteria Products Prevent AKI Induced by Ischemia-Reperfusion. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN. 2015;26:1877–1888. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014030288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mazmanian SK, Round JL, Kasper DL. A microbial symbiosis factor prevents intestinal inflammatory disease. Nature. 2008;453:620–625. doi: 10.1038/nature07008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Atarashi K, et al. Induction of colonic regulatory T cells by indigenous Clostridium species. Science. 2011;331:337–341. doi: 10.1126/science.1198469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Szeto CC, et al. Endotoxemia is related to systemic inflammation and atherosclerosis in peritoneal dialysis patients. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2008;3:431–436. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03600807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stearns-Kurosawa DJ, Osuchowski MF, Valentine C, Kurosawa S, Remick DG. The pathogenesis of sepsis. Annual review of pathology. 2011;6:19–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goncalves S, et al. Associations between renal function, volume status and endotoxaemia in chronic kidney disease patients. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation: official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2006;21:2788–2794. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McIntyre CW, et al. Circulating endotoxemia: a novel factor in systemic inflammation and cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2011;6:133–141. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04610510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]