Abstract

Fibromyalgia is a multifaceted chronic pain syndrome and the integration of different health disciplines is strongly recommended for its care. The interventions based on this principle are very heterogeneous and the difference across their structures has not been extensively studied, leading to incorrect conclusions when their outcomes are pooled. The objective of this mapping review was to summarize the characteristics of these programs, with particular focus on the integration of their components. We performed a search of the literature about treatments for fibromyalgia involving multiple disciplines on PubMed and Scopus. Starting from 560 articles, we included 22 noncontrolled studies, 10 controlled studies, and 17 RCTs evaluating the effects of 38 multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary interventions. The average quality of the studies was low. Their outcomes were usually pain intensity, quality of life, and psychological variables. We created a map of the programs based on the degree of integration of the included disciplines, which ranged from a juxtaposition of few components to a complex harmonization of different perspectives obtained through teamwork strategies. The rehabilitation programs were then thoroughly described with regard to the duration, setting, therapeutic components, and professionals included. The implications for future quantitative reviews are discussed.

1. Introduction

Fibromyalgia is a chronic pain condition of unknown etiology which affects mainly women and is characterized by stiffness, fatigue, disturbed sleep, cognitive impairment, and psychological distress, posing a significant threat to the quality of life of affected individuals [1–3]. The complex features of the syndrome and its various symptoms are partially explained by central sensitization processes that interact with psychological and social factors, leading to a phenomenon where the impact of each component is multiplied and acts in a synergic manner [4, 5]. Given its multifaceted nature and the poor efficacy of standard medical interventions, the integration of different health disciplines for its understanding and for the development of specific treatments has long been advocated [6–10]. As a result, a large number of interventions combining techniques drawn from different fields (e.g., medicine, psychology, and physical therapy) have been developed and have proven to be effective for the improvement of the various symptoms of the syndrome [11–15]. Nonetheless, these programs are very heterogeneous in terms of duration, objectives, setting, format, therapeutic components, and professionals involved. This great variability is reflected by different organizational frameworks of the pain treatment facilities and casts some doubt on the possibility of pooling the results of trials evaluating their interventions [16, 17]. The composition of the rehabilitation teams and the integration between their members seem to be especially important in distinguishing the various programs, since there is a wide difference with regard to how their various disciplines are harmonized, combined, or juxtaposed. Conversely, terms such as “multimodal,” “multicomponent,” “multidisciplinary,” and “interdisciplinary” are often used as synonyms [18, 19]. From a theoretical point of view, the difference between these concepts is substantial. The terms “multimodal” and “multicomponent” have not received yet a clear definition. Multimodality generally refers to the combination of multiple therapeutic components, not necessarily provided by different operators. The expression “multicomponent treatments” indicates the presence of interventions provided by different team members, without clarifying how they are integrated [20]. Conversely, the other two terms define how these components are combined. Multidisciplinarity refers to the addition of the competencies of multiple professionals who stay within the boundaries of their fields, whereas interdisciplinarity denotes that the various disciplines are coordinated toward a common and coherent approach [19]. Multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary treatments are therefore conceptually different and this difference should be reflected in their structures. Especially in the case of programs addressing a complex disorder, such as the fibromyalgia syndrome, this issue must be taken into account for the sake of a critical appraisal of the literature, which can be a preliminary step for quantitative synthesis. The objective of this review of the literature is therefore to describe, map, and summarize the characteristics of treatments for fibromyalgia involving multiple health disciplines, with a focus on how these disciplines are integrated.

2. Methods

A mapping review of the literature was performed. Mapping reviews usually aim to retrieve, catalog, and map all the evidence about a research topic [21, 22]. We adapted their methodological design in order to use rehabilitation programs as units of analysis. Therefore, instead of investigating the characteristics and the results of the included papers, we focused on the information about the interventions that were described.

We conducted a comprehensive search in PubMed and Scopus of all the available original research reports describing and evaluating multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, or multicomponent interventions for fibromyalgia up to April 2016. We used these keywords in both databases: fibromyalgia, multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, multicomponent, and integrated treatments. The studies were scanned according to the inclusion (description and evaluation of a multicomponent intervention involving at least two operators from different disciplines, fibromyalgia as primary diagnosis, and English language) and exclusion (review as publication type, single-case studies, and workplace interventions) criteria. Since our aim was to describe the various treatment programs and we were not interested in a quantitative evaluation of their outcomes, we included both RCTs, nonrandomized trials and noncontrolled trials. We also included studies evaluating outcome predictors, if they provided data about the effects of the interventions. A first scanning was based only on the titles and the abstracts of the retrieved research articles. After this first step, the full text of the remaining papers was accessed and we assessed the methodological quality of the studies. Since we included both controlled and noncontrolled trials, we adapted the SIGN checklist for randomized controlled trials [23] adding four items from the Downs and Black Checklist [24] (i.e., use of appropriate analyses, assessment of confounders, use of a representative sample, and intervention integrity) (Table 1). We used its scores to rate the studies as of “high,” “medium,” “low,” and “insufficient” quality. Questions from 2 to 6 were not considered during the evaluation of noncontrolled studies.

Table 1.

Adapted SIGN checklist.

| (1) | The study addresses an appropriate and clearly focused question. |

| (2) | The assignment of subjects to treatment groups is randomized. |

| (3) | An adequate concealment method is used. |

| (4) | The design keeps subjects and investigators “blind” about treatment allocation. |

| (5) | The treatment and control groups are similar at the start of the trial. |

| (6) | The only difference between groups is the treatment under investigation. |

| (7) | All relevant outcomes are measured in a standard, valid, and reliable way. |

| (8) | Were the statistical tests used to assess the main outcomes appropriate? |

| (9) | Were those subjects who were prepared to participate representative of the entire population from which they were recruited? |

| (10) | What percentage of the individuals recruited into each treatment arm of the study dropped out before the study was completed? |

| (11) | Are all the subjects analyzed in the groups to which they were randomly allocated (application of an intention-to-treat analysis)? |

| (12) | Where the study is carried out at more than one site, results are comparable for all sites. |

| (13) | Are the distributions of principal confounders in each group of subjects to be compared clearly described? |

| (14) | How well was the study done to minimize bias? |

| (15) | Is the overall effect due to the study intervention? |

Note. During the assessment of noncontrolled studies, items from (2) to (6) were not considered.

We then employed a specifically created data extraction sheet to retrieve all the available information about number of study participants, dropout, professionals involved in the treatment, group/individual setting, inpatient/outpatient format, duration, components of the interventions, and treatment outcomes. When possible, we tried to locate and report the information about how the different disciplines are integrated with each other, in order to provide a brief outline of the program. In case of unclear or missing information, we initially tried to locate other descriptions consulting other studies of the same authors. If no other relevant studies were found, we tried to contact the authors of the articles and we asked them for additional information. All the data about the treatments were finally inserted in a MS Excel spreadsheet and were used to map the included interventions.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

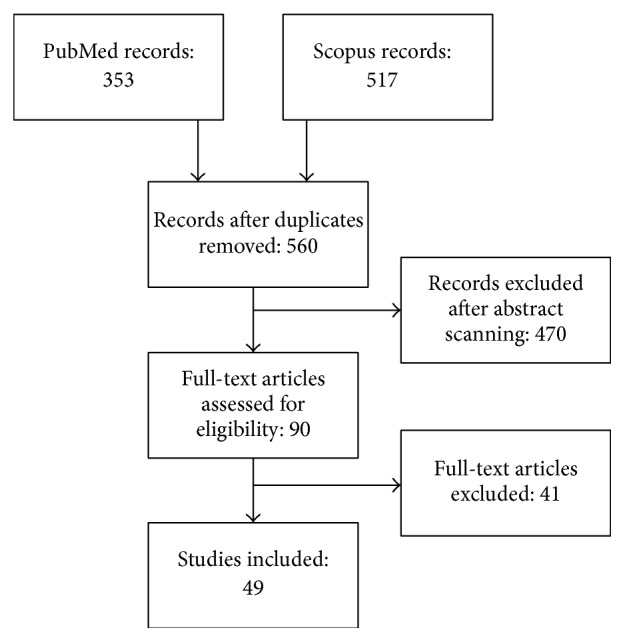

The initial database search identified 560 records, of which 90 were selected for a full-text examination. The final database included 49 papers describing 38 different interventions that were administered to a total of 6013 subjects (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart diagram for study selection.

We found 22 papers describing noncontrolled studies, 10 describing controlled studies, and 17 describing RCTs (Table 2). The majority of the articles mainly reported the effects of a multicomponent treatment, whereas six papers mainly reported analyses on outcome predictors, one trial compared two multidisciplinary treatments, and three trials evaluated the effects of adding a treatment component to existing multidisciplinary treatments. The average methodological quality of the studies was low; 3 noncontrolled trials, 5 controlled trials, and 10 RCTs were rated as of medium quality and 6 studies were rated as of high quality. Their outcomes were usually pain intensity, psychological variables (such as anxiety, depression, distress, pain catastrophizing, coping skills, and self-efficacy), quality of life, and improvement in the overall score of the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire.

Table 2.

Description of the included studies.

| Reference | Country | Design | Type of study | Comparison group | Subjects (dropout) | Outcomes | Overall quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Åkerblom et al., 2015 [25] | Sweden | Noncontrolled study | Outcome predictors | N/A | 409 (145) | Pain, psychological factors, pain interference | Medium |

| Amris et al., 2014 [26] | Netherlands | RCT | Comparison with control | WL | 191 (21) | QOL, pain, psychological factors, FIQ, movement | High |

| Anderson and Winkler, 2006 [27] | US | Controlled trial | Comparison with control | TAU | 98 (5) | QOL, pain, psychological factors, FIQ, tender points | Low |

| Angst et al., 2006 [28] | Switzerland | Noncontrolled study | Comparison with control | TAU | 225 (100) | QOL, pain, pain interference, psychological factors | Low |

| Angst et al., 2009 [29] | Controlled trial | Pre-post evaluation | TAU | 331 (121) | QOL, pain, psychological factors | Low | |

| Bailey et al., 1999 [30] | Canada | Noncontrolled study | Pre-post evaluation | N/A | 149 (43) | Pain, pain interference, psychological factors, FIQ, physical fitness | Low |

| Bourgault et al., 2015 [31] | Canada | RCT | Comparison with control | WL | 58 (15) | QOL, pain, psychological factors, pain interference, FIQ, perception of improvement | Medium |

| Carbonell-Baeza et al., 2011 [32] | Spain | Controlled trial | Comparison with control | TAU + education | 75 (10) | Tender points count, pain threshold, physical fitness, BMI | Medium |

| Carbonell-Baeza et al., 2011 [33] | Controlled trial | Comparison with control | TAU + education | 75 (10) | QOL, pain, psychological factors, FIQ | Medium | |

| Carbonell-Baeza et al., 2012 [34] | Controlled trial | Comparison with additional treatment | Biodanza | 38 (7) | QOL, pain, psychological factors, FIQ, physical fitness, tender points | Medium | |

| Casanueva-Fernández et al., 2012 [35] | Spain | RCT | Comparison with control | TAU + education | 34 (6) | QOL, pain, psychological factors, FIQ, fatigue, sleep, tender points count, pain threshold, physical fitness | Medium |

| Castel et al., 2013 [36] | Spain | RCT | Comparison with control | TAU | 155 (28) | Pain, psychological factors, FIQ, sleep | High |

| Cedraschi et al., 2004 [37] | Switzerland | RCT | Comparison with control | WL | 164 (35) | QOL, pain, psychological factors, FIQ, tender points count, satisfaction | High |

| De Rooij et al., 2013 [38] | Netherlands | Noncontrolled study | Outcome predictors | N/A | 138 (18) | Pain, psychological factors, pain interference, perception of improvement | Low |

| Gustafsson et al., 2002 [39] | Sweden | Controlled trial | Comparison with control | TAU | 43 (2) | Movement, pain drawings, pain, QOL, pain interference | Low |

| Hammond and Freeman, 2006 [40] | UK | RCT | Comparison with control | Relaxation training | 183 (80) | FIQ, psychological factors, physical activity, healthcare use, perception of improvement | Medium |

| Hamnes et al., 2012 [41] | Norway | RCT | Comparison with control | WL | 147 (29) | Psychological factors, FIQ, care-management skills | Medium |

| Hooten et al., 2007 [42] | US | Noncontrolled study | Comparison between male and female | N/A | 66 (7) | QOL, pain, psychological factors, pain interference, drug usage | Low |

| Hooten et al., 2007 [43] | Noncontrolled study | Pre-post evaluation | N/A | 159 (17) | QOL, pain, pain interference, activity, psychological factors | Low | |

| Kas et al., 2015 [44] | US | Controlled trial | Comparison with additional treatment | Multidisciplinary + increased exercise | 79 (0) | FIQ | Medium |

| Keel et al., 1998 [45] | Switzerland | RCT | Comparison with control | Relaxation training | 32 (5) | Pain, psychological factors, sleep, changes in drug treatment, satisfaction | Low |

| Kroese et al., 2009 [46] | Netherlands | Noncontrolled study | Pre-post evaluation | N/A | 105 (5) | FIQ, QOL, satisfaction | Low |

| van Eijk-Hustings et al., 2013 [47] | RCT | Comparison with control | Aerobic exercise and TAU | 203 (69) | QOL, activity, FIQ, healthcare use, sick leave | Medium | |

| Lemstra and Olszynski, 2005 [48] | Canada | RCT | Comparison with control | Family physician | 79 (8) | Pain, pain interference, psychological factors | High |

| Lera et al., 2009 [49] | Spain | RCT | Comparison with additional treatment | Multidisciplinary + CBT | 83 (27) | QOL, FIQ, psychological factors, tender points count | High |

| Marcus et al., 2014 [50] | US | Noncontrolled study | Pre-post evaluation | N/A | 274 (67) | Pain, ADL, movement, FIQ | Low |

| Martìn et al., 2012 [51] | Spain | RCT | Comparison with control | Pharmacotherapy | 180 (70) | QOL, pain, psychological factors, pain interference, FIQ, satisfaction | Medium |

| Martìn et al., 2014 [52] | RCT | Comparison with control | Pharmacotherapy | 180 (70) | FIQ, psychological factors, satisfaction | Medium | |

| Martìn et al., 2014 [53] | RCT | Comparison with control | Pharmacotherapy | 180 (70) | FIQ | Medium | |

| Martìn et al., 2014 [54] | RCT | Comparison with control | Pharmacotherapy | 180 (70) | Pain, FIQ | Medium | |

| Martins et al., 2014 [55] | Brazil | Controlled trial | Comparison with control | TAU | 27 (0) | QOL, pain, psychological factors, FIQ, sleep | Low |

| Mengshoel et al., 1995 [56] | Norway | Noncontrolled study | Pre-post evaluation | N/A | 16 (3) | Pain, fatigue, sleep, adjustments of daily life | Low |

| Michalsen et al., 2013 [57] | Germany | Controlled trial | Comparison with additional treatment | Other multidisciplinary treatments | 48 (6) | Pain, psychological factors, FIQ, sleep, BMI | Medium |

| Nielson and Jensen, 2004 [58] | Canada | Noncontrolled study | Outcome predictors | N/A | 253 (55) | QOL, pain, psychological factors, pain interference, activity | Medium |

| Persson et al., 2012 [59] | Sweden | Noncontrolled study | Pre-post evaluation | N/A | 813 (304) | Pain, psychological factors, pain interference, activity | Low |

| Ripley et al., 2003 [60] | US | Noncontrolled study | Pre-post evaluation | N/A | 21 (0) | Pain, psychological factors, FIQ, fatigue, sleep, comorbidities | Low |

| Romeyke et al., 2014 [61] | Austria | Controlled trial | Comparison with control | Multidisciplinary + hyperthermia | 104 (0) | Pain, chronic pain stage, severity of symptoms, pain interference | Low |

| Salgueiro et al., 2013 [62] | Spain | Noncontrolled study | Outcome predictors | N/A | 72 (0) | Pain, FIQ, QOL, psychological factors | Low |

| Saral et al., 2016 [63] | Turkey | RCT | Comparison with control | Long term versus short term versus no treatment | 66 (7) | QOL, pain, psychological factors, FIQ, fatigue, sleep, tender points count, pain threshold, physical functioning | Medium |

| Stein and Miclescu, 2013 [64] | Sweden | Noncontrolled study | Pre-post evaluation | N/A | 59 (8) | Pain, psychological factors, QOL, sick leave duration, healthcare use, drug usage | Low |

| Suman et al., 2009 [65] | Italy | Noncontrolled study | Pre-post evaluation | N/A | 25 (0) | Pain, psychological factors, tender points count, pain threshold | Low |

| Turk et al., 1998 [66] | US | Noncontrolled study | Pre-post evaluation | N/A | 70 (3) | Pain, psychological factors, pain interference, FIQ, disability, marital satisfaction | Medium |

| Van Koulil et al., 2011 [67] | Netherlands | RCT | Comparison with control | WL | 158 (45) | Physical fitness | High |

| van Wilgen et al., 2007 [68] | Netherlands | Noncontrolled study | Pre-post evaluation | N/A | 65 (0) | QOL, pain, psychological factors, FIQ, physical fitness | Low |

| Wennemer et al., 2006 [69] | US | Noncontrolled study | Pre-post evaluation | N/A | 23 (3) | QOL, FIQ, movement | Low |

| Worrel et al., 2001 [70] | US | Noncontrolled study | Pre-post evaluation | N/A | 100 (26) | Pain, psychological factors, FIQ, pain interference, sleep, fatigue | Low |

| Pfeiffer et al., 2003 [71] | Noncontrolled study | Pre-post evaluation | N/A | 100 (22) | QOL, FIQ, psychological factors | Low | |

| Oh et al., 2010 [72] | Noncontrolled study | Pre-post evaluation | N/A | 984 (463) | QOL, FIQ, satisfaction | Low | |

| Vincent et al., 2013 [73] | Noncontrolled study | Pre-post evaluation | N/A | 7 (0) | QOL, FIQ, psychological factors, fatigue | Low |

3.2. Multidisciplinary and Interdisciplinary Programs

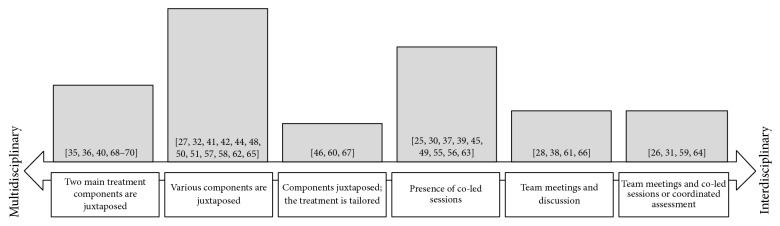

Among the studies included in the review, the terms “multimodal” and “multicomponent” were rarely employed and were never used as primary descriptors of the structure of the interventions, whereas 25 treatments were defined as “multidisciplinary” and 11 as “interdisciplinary.” However, there was not a clear distinction between these concepts. In some cases, the terms were used interchangeably or were incorrectly employed (e.g., [71, 73] or [62]). More generally, the programs were very heterogeneous with regard to the strategies that were employed to integrate the different perspectives of the operators and can be mapped in a continuum which starts with multidisciplinary treatments involving few disciplines whose components are simply added and ends with more complex interventions that are based on a coordinated assessment and care (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Map of the rehabilitation programs. Note. The height of the bars is proportional to the frequency of the interventions included in the relative category. The references of the studies describing these interventions are in brackets.

Most of the treatments were based on various components that were juxtaposed, so that the patient met the different health operators in different moments of the program in a standardized manner. A few interventions were more flexible and allowed the operators to tailor the programs, in terms of number and intensity of the therapeutic components, to the needs and characteristics of the patients. More integrated approaches were organized so that some or the majority of the treatment sessions were led by two or more professionals jointly. In other cases, weekly team meetings were planned to discuss the patients, allowing a constant dialog between the operators. This could be added to other strategies, such as providing education about interdisciplinary work or tailoring the various components to the patients, in order to provide more effective integration of the different disciplines.

3.3. Description of the Interventions

The main characteristics of the interventions are reported in Table 3. Most of the programs were based on an outpatient setting; only five intensive treatments were provided in hospital inpatient services. Only four programs were mainly administered individually, six interventions included both group and individual activities, and the other 28 treatments were mainly group-based. There was a great variety with regard to the duration and the intensity of the interventions. The median duration was 7 weeks, but there were both very brief treatments lasting for less than a week (e.g., [70]) and very long treatments lasting for one year (e.g., [27]). With regard to the intensity, there were both intensive programs (e.g., [28]) and interventions including less than twelve hours of therapies (e.g., [70]), with a median of 42 hours of treatment.

Table 3.

Description of the rehabilitation programs.

| Reference | Approach | Format | Setting | Weeks | Hours | Professionals | Therapeutic components | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Åkerblom et al., 2015 [25] | Multidisciplinary | Group | Outpatient | 5 | 126 | Psychologist, physician, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, social worker | Education, exercise, CBT, pain management techniques, relaxation, occupational therapy | Program for chronic pain rehabilitation based on a CBT framework. The group sessions are jointly conducted. The patient's caregiver is involved. Includes a follow-up intervention. |

|

| ||||||||

| Amris et al., 2014 [26] | Interdisciplinary | Group | Outpatient | 2 | 35 | Psychologist, physician, nurse, physiotherapist, occupational therapist | Education, exercise, group discussion, pain management techniques | Scheduled team conferences, with a session jointly conducted by the psychologist and the rheumatologist. |

|

| ||||||||

| Anderson and Winkler, 2006 [27] | Multidisciplinary | Individual | Outpatient | 48 | N/A | Psychologist, physician, nurse, physiotherapist, dietitian, aquatic fitness instructor | Education, land and pool exercise, auricular therapy, microcurrent therapy, CBT, massage, nutritional counseling | Program based on three phases with different treatment intensities. The various components are juxtaposed. |

|

| ||||||||

| Angst et al., 2006 [28] Angst et al., 2009 [29] |

Interdisciplinary | Both | Inpatient | 4 | 100 | Psychologist, physician, nurse, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, Qi-gong instructor, creative and humor therapists | Education, exercise, group discussion, CBT, pain management techniques, Qi-gong, humor therapy | Based on the integration of traditional and Chinese medicine, exercise and physiotherapy, and different psychotherapeutic methods. The team received education on interdisciplinary work and participates in weekly meetings. |

|

| ||||||||

| Bailey et al., 1999 [30] | Interdisciplinary | Group | Outpatient | 12 | 72 | Physiotherapist, occupational therapist, social worker. The team is supported by pharmacist, dietitian, kinesiologist | Education, exercise, discussion, pain management techniques | Based on exercise and education, performed by an interdisciplinary group and a supporting group; patients can access the members of the teams. |

|

| ||||||||

| Bourgault et al., 2015 [31] | Interdisciplinary | Group | Outpatient | 11 | 22,5 | Physician, facilitator expert in the psychological area and facilitator expert in the physical area | Education, exercise, group discussion, pain management techniques based on CBT | Based on interactive sessions jointly conducted by the two operators, who are described as “facilitators.” The exercises and psychological components are tailored to the single patient. |

|

| ||||||||

| Carbonell-Baeza et al., 2011 [32] Carbonell-Baeza et al., 2011 [33] |

Multidisciplinary | Group | Outpatient | 12 | 45 | Psychologist, physiotherapist, fitness specialist | Education, exercise, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, pain management techniques, massage | The program is based on exercise and education; the exercise sessions are supervised by both a physiotherapist and a fitness specialist. |

| Carbonell-Baeza et al., 2012 [34] | 16 | 60 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Casanueva-Fernández et al., 2012 [35] | Multidisciplinary | Individual | Outpatient | 8 | 8 | The team is not described | Education, exercise, ischemic pressure, massage, thermal therapy | The medical treatment is associated with a program of education and physical treatments. |

|

| ||||||||

| Castel et al., 2013 [36] | Multidisciplinary | Group | Outpatient | 12 | 48 | Psychologist, physiotherapist | Exercise, CBT | The pharmacologic treatment is accompanied by CBT and physical therapy. |

|

| ||||||||

| Cedraschi et al., 2004 [37] | Multidisciplinary | Group | Outpatient | 6 | 18 | Physician, physiotherapist, occupational therapist | Education, pool and land exercise, group discussion, pain management techniques | The program is based on the patient's self-management of his/her symptoms. The educational sessions are conducted by the whole multidisciplinary team. |

|

| ||||||||

| De Rooij et al., 2013 [38] | Multidisciplinary | Both | Outpatient | 7 | 49 | Psychologist, physician, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, social worker | Education, exercise, CBT, pain management techniques | The program is tailored to the patient's goals and regular meetings are scheduled to facilitate team discussions. |

|

| ||||||||

| Gustafsson et al., 2002 [39] | Multidisciplinary | Group | Outpatient | 12 | 104 | Physician, nurse, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, social worker | Education, exercise, group discussion, pain management techniques | The education component is jointly administered by the nurse and the physiotherapist. At the end of the program, the team members meet at a conference the patient, his employer, and the local insurance officer to discuss the treatment plan. |

|

| ||||||||

| Hammond and Freeman, 2006 [40] | Education-exercise program | Group | Outpatient | 10 | 20 | Physiotherapist, occupational therapist | Education, exercise | Education is also based on self-management. The program is administered by either the physiotherapist or the occupational therapist, whereas the other one acts as a supervisor. |

|

| ||||||||

| Hamnes et al., 2012 [41] | Multidisciplinary | Group | Inpatient | 1 | 70 | Physician, nurse, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, social worker, dietitian | Education, exercise, group discussion, pain management techniques based on cognitive-behavioral principles, nutritional counseling | Complex and intensive treatment based on self-management, with involvement of the patient's partner. The different therapeutic components are juxtaposed. |

|

| ||||||||

| Hooten et al., 2007 [42] Hooten et al., 2007 [43] |

Multidisciplinary | Both | Outpatient | 3 | 150 | Psychologist, mental health therapist, physician, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, nurse, chemical dependency counselors | Education, exercise, CBT, pain management techniques based on a cognitive-behavioral framework, biofeedback, relaxation, opioid discontinuation | Description of the treatment found in the research by Townsend et al., 2008 [74]. The team includes a large number of operators from various disciplines. Gradual withdrawal from opioids under the supervision of the physician. |

|

| ||||||||

| Kas et al., 2015 [44] | Multidisciplinary | Individual | Outpatient | 10 | 25–40 | Psychologist, physician, physiotherapist, occupational therapist | Aerobic and strengthening exercise, CBT/Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, biofeedback, occupational therapy | The study evaluates the effects of adding strength exercises to an existing multidisciplinary treatment. The various components are juxtaposed. |

|

| ||||||||

| Keel et al., 1998 [45] | Integrated treatment | Group | Outpatient | 15 | 30 | Physiotherapist, psychologist, psychiatrist | Exercise, education, pain management strategies, relaxation, discussion | Integrated psychological group treatment based on self-management. The sessions are jointly led by the operators. |

|

| ||||||||

| Kroese et al., 2009 [46] | Multidisciplinary | Group | Outpatient | 12 | 108 | Psychologist, physiotherapist, occupational therapist | Education, exercise, group discussion, pain management techniques, sociotherapy, creative arts therapy | Physicians are not involved in order to prevent the medicalization of the syndrome. Five aftercare meetings are scheduled to prevent relapses. Based on the patient's needs, more intensive therapeutics could be added. |

| van Eijk-Hustings et al., 2013 [47] | 12 + aftercare | 108 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Lemstra and Olszynski, 2005 [48] | Multidisciplinary | Group | Outpatient | 6 | 24 | Physician, psychologist, physiotherapist, massage therapist, dietitian | Exercise, pain management techniques, education, massage | The program includes rheumatologist and physical therapist intake, group exercise and education, individual massage therapy sessions, and rheumatologist and physical therapist discharge. |

|

| ||||||||

| Lera et al., 2009 [49] | Multidisciplinary | Group | Outpatient | 16 | 14 | Physician, physiotherapist, rehabilitation practitioner, additional group: psychologist | Education, exercise, additional group: CBT | Supported by an individual medical treatment, four of the fourteen sessions are jointly conducted by the rheumatologist and a rehabilitation practitioner. |

|

| ||||||||

| Marcus et al., 2014 [50] | Multidisciplinary | Group | Outpatient | 6 | 36–48 | Psychologist, physician, physiotherapist, occupational therapist | Education, exercise, CBT, pain management techniques | Mainly based on education, exercise, and the development of pain management skills. |

|

| ||||||||

| Martìn et al., 2012 [51] Martìn et al., 2014 [52] Martìn et al., 2014 [53] Martìn et al., 2014 [54] |

Interdisciplinary | Group | Outpatient | 6 | 21 | Psychologist, physician, physiotherapist | Education, exercise, CBT, pain management techniques, massage | The psychological, medical, educational, and physiotherapeutic approaches are coordinated; however, there is no information about this process. |

|

| ||||||||

| Martins et al., 2014 [55] | Interdisciplinary | Group | Outpatient | 12 | 12 | Psychologist, physician, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, social worker | Education, exercise, pain management techniques based on cognitive-behavioral principles | It is unclear how the operators are integrated. |

|

| ||||||||

| Mengshoel et al., 1995 [56] | Multidisciplinary | Group | Outpatient | 10 | 20 | Physician, physiotherapist, dietitian | Education, exercise, group discussion | Based on lessons and exercise sessions jointly conducted by two team members. |

|

| ||||||||

| Michalsen et al., 2013 [57] | Multidisciplinary | Group | Inpatient | 2 | N/A | Psychologist, physician, physiotherapist | Land and pool exercise, thermal therapy, CBT, education, additional group: fasting and nutritional therapy | Intensive programs; the components are juxtaposed. |

|

| ||||||||

| Nielson and Jensen, 2004 [58] | Multidisciplinary | Both | Outpatient | 4 | N/A | Psychologist, physician, physiotherapist, occupational therapist | Education, exercise, CBT, occupational therapy, opioid tapering | Aimed at improving pain management skills and physical and psychological functioning, based on a cognitive-behavioral model. |

|

| ||||||||

| Persson et al., 2012 [59] | Interdisciplinary | Both | Outpatient | 5 | 150 | Psychologist, physician, nurse, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, social worker | Education based on cognitive-behavioral principles, exercise, group discussion, biofeedback, pain management techniques | Based on teamwork, each operator is educated about the tools of all the disciplines and about cognitive-behavioral techniques. Includes team-based lectures; the operators participate in weekly meetings. The treatment is tailored to the patient during the first week. In the first and last weeks, individual sessions are scheduled and a final meeting with the patient, his/her caregiver, his/her employer, and the local insurance officer is planned. The team visits the patient's workplace and his/her caregiver is involved. Follow-up meeting two months after discharge. |

|

| ||||||||

| Ripley et al., 2003 [60] | Multidisciplinary | Individual | Outpatient | 24 | N/A | Psychologist, physician, nurse, occupational therapist | Education, dietary modification, pain management techniques, nutraceuticals | Initial screening made by a physician with a social worker who evaluates with the family whether the patient is able and willing to complete the program and recommends if needed to add to the treatment also psychological counseling, group sessions, or other strategies. The treatment is tailored to the patient's needs and based on the response to the different therapeutic components. |

|

| ||||||||

| Romeyke et al., 2014 [61] | Interdisciplinary | Group | Inpatient | 2 | N/A | Psychologist, physician, nurse, physiotherapist, naturopathy specialist, ergonomic specialist | Hyperthermia, exercise, CBT, pain management techniques, massage | The nurses supervise the treatment and act as process coordinators. Weekly team meetings are scheduled. |

|

| ||||||||

| Salgueiro et al., 2013 [62] | Multidisciplinary | Both | Outpatient | 4 | 60 | Psychologist, physician, nurse, occupational therapist | Pharmacotherapy, CBT, exercise, pain management techniques, occupational therapy, education | Complex intervention including pharmacotherapy, CBT, physical and occupational therapy, and education, with focus on tackling the patient's misconception about the syndrome. |

|

| ||||||||

| Saral et al., 2016 [63] | Interdisciplinary | Group | Outpatient | 10 | 46 | Psychologist, physician, physiotherapist | Education, exercise, CBT | The long-term program includes a full day of education led by the investigators and then a group CBT along with a program of physical therapy with prescription of home exercises. The short-term program includes the same therapeutic components administered in two days. |

|

| ||||||||

| Stein and Miclescu, 2013 [64] | Multidisciplinary | Group | Outpatient | 6 | 60 | Psychologist, physician, physiotherapist, occupational therapist | Education, exercise, CBT | Interdisciplinary assessment and discussion during the intake; at the end, two or three operators in representation of the whole team meet the patient and his/her family members. There is the possibility for the patient to individually contact the operators. The patient meets again the whole team at the end of the treatment; his/her employer and other key figures are invited. |

|

| ||||||||

| Suman et al., 2009 [65] | Multidisciplinary | Individual | Inpatient | 3 | 75 | Psychologist, physician, physiotherapist | Education, exercise, CBT | Academic setting; at each weekend, the patient returns to his/her home and tries to practice pain management skills. The treatment components are juxtaposed. |

|

| ||||||||

| Turk et al., 1998 [66] | Interdisciplinary | Group | Outpatient | 4 | 24 | Psychologist, physician, physiotherapist, occupational therapist | Education, exercise, CBT, pain management techniques | Each half-day session includes medical, physical, psychologic, and occupational components. Team meetings are planned; the treatment is supervised by a rheumatologist. |

|

| ||||||||

| Van Koulil et al., 2011 [67] | Multidisciplinary | Group | Outpatient | 8 | 32 | Psychologist, physiotherapist, social worker | Exercise, CBT, pain management techniques | The treatment is mainly based on CBT and exercise; the intervention is tailored to the patient. |

|

| ||||||||

| van Wilgen et al., 2007 [68] | Multidisciplinary | Group | Outpatient | 17 | N/A | Physiotherapist, occupational therapist, social worker, trainer | Education, exercise, relaxation | Mainly based on education and physical therapy, provided by trainers and physical therapists. |

|

| ||||||||

| Wennemer et al., 2006 [69] | Multidisciplinary | Group | Outpatient | 8 | 48 | Physician, physiotherapist, occupational therapist | Education, Feldenkrais or Tai-Chi exercise, relaxation, occupational therapy | Progressive program incorporating education, exercise, and stress reduction techniques. |

|

| ||||||||

| Worrel et al., 2001 [70] Pfeiffer et al., 2003 [71] Oh et al., 2010 [72] |

Interdisciplinary | Group | Outpatient | <1 | 8 | Physician, nurse, physical and occupational therapist | Education, exercise, group discussion, pain management techniques | During the first day, the nurse is responsible for the assessment phase, leads the first education session, and facilitates a group discussion. The day after, physical and occupational therapists complete the program with lectures and exercises. Other professionals are involved if necessary. The participation of the patient's family is encouraged. |

| Vincent et al., 2013 [73] | 1 | 42 | Psychologist, physician, nurse, physiotherapist, occupational therapist | Patient education, family education, pain management techniques | Modified version of the FTP treatment. The program is implemented in one week and includes the same components plus planned involvement of the family members and follow-up contacts with the nurse. | |||

The number and the choice of the disciplines that were integrated in the various interventions were very variable, as well as their relative importance. As a consequence, it was not possible to categorize the programs creating clusters based on the professionals included. Physicians, physical therapists, and psychologists were the most employed operators, followed by occupational therapists, nurses, social workers, dietitians, and other professionals such as Qi-gong instructors, kinesiologists, and massage therapists.

The main therapeutic components included in the various rehabilitation programs were education about fibromyalgia and physical exercise, which were present in 36 out of 38 programs. Education was generally based on group lectures about the syndrome, its symptoms, its prognosis, and the biopsychosocial factors influencing its long-term progression and its daily course. The prescribed physical activity was various and included aerobic, pool, and strengthening exercises. 19 programs provided some psychotherapy sessions under the cognitive-behavioral approach, generally focused on symptom management. Both the educational lectures and the psychotherapeutic sessions could also be focused on teaching the patients to self-manage their symptoms and on enhancing group discussions among the participants. Besides these common therapeutic components, other forms of interventions were usually provided. These include, for instance, occupational therapies, biofeedback, massage therapies, relaxation, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy sessions, and dietary counseling.

4. Discussion

The objective of this review was to describe the characteristics of the available integrated interventions for fibromyalgia, focusing on how the different disciplines are integrated with each other. Our study, therefore, is embedded in two lines of inquiry, that is, the discussion about multidisciplinarity and interdisciplinarity in the healthcare and the evaluation of multicomponent treatment for chronic pain conditions.

With regard to the first, our study is in line with and finds support for the predominant theoretical perspective which describes multidisciplinarity and interdisciplinarity as two parts of the same continuum [18, 19]. Employing the original perspective of analyzing how the integration of the different disciplines is provided by the various programs, we found that the possible organizational frameworks are multiple and are characterized by different degrees of complexity. On the one hand, less integrated programs provide a juxtaposition of two or more different disciplines, which are simply added. These programs can be seen as the prototype of multidisciplinary interventions, since every operator works independently, there is no overlap between the different treatment modalities, and the program is generally organized in a vertical manner [75]. However, we found that there are multidisciplinary programs which use a more flexible and integrated framework, which allows us to modify the treatment and to involve the patient in the decisions about his/her care. In more cohesive programs, some or the majority of the education or pain management sessions are jointly conducted by different operators, allowing the professionals to build a shared perspective regarding the various topics. Prototypical interdisciplinary models seem however to be based on weekly team discussions about the patients, which can be accompanied by other strategies, such as education about interdisciplinary work, a coordinated assessment, or providing sessions jointly conducted by the operators. The presence of team meetings seems to be considered by the authors of the studies included in this review as the main characteristic which defines their treatment as “interdisciplinary,” partly overlooking other components such as creating common goals, making team conferences with the patient and his/her family, and providing shared leadership and a comprehensive assessment [75, 76].

With regard to the evaluation of the multicomponent interventions for fibromyalgia, our study represents a first step for conducting a quantitative synthesis of the literature. As we had hypothesized, we found that the programs included in our review were very heterogeneous in terms of number, type, and integration of the components and professionals, as well as in terms of duration and intensity. Previous analyses of the literature did not successfully address this diversity. Hauser and colleagues [20] performed a meta-analysis on 7 RCTs evaluating multicomponent treatments for fibromyalgia, finding support for their short-term efficacy. The author conducted a sensitivity analysis based only on the methodologic quality and the duration of the programs. A previous Cochrane review [77] attempted to include all the interventions which contained both a medical and a psychological, social, or vocational component, finding four RCTs and showing that these interventions did not provide quantifiable benefits. Different from our study, the authors did not address the differences with regard to format, setting of the program, and integration of operators and therapeutic components. More recently, Papadopoulou et al. [11] evaluated all the pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions for fibromyalgia, finding support for multidisciplinary treatments based on 8 RCTs, which were not described. Similarly, other reviews focusing on various chronic pain conditions found that multicomponent programs are effective for the treatment of fibromyalgia but did not address their heterogeneity [12, 78]. Our study was not aimed at a quantitative evaluation of the outcomes of these programs but provides a detailed description of the various programs identifying some key characteristics that must be taken into account by future systematic reviews and meta-analyses. In particular, the most varying factors were the duration and the intensity of the programs, the treatment components, and the strategies of integration of the operators. It is needed that future quantitative reviews separately analyze studies evaluating treatments with different structures and assess the moderator effect of the temporal characteristics of the programs.

Some important remarks need to be made. On the one hand, we focused only on studies which included multiple disciplines performed by multiple operators. Therefore, we excluded the papers which did not state clearly that multiple professionals were present and we focused on programs performed by rehabilitation teams. As a consequence, our description is limited to these treatments and it is possible that some multidisciplinary programs were excluded due to poor descriptions of their structure. In addition, our findings are based on brief reports included in scientific papers, and it is possible that important characteristics of the evaluated interventions were missing and that the whole of the multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary rehabilitation programs is misrepresented by our sample. Finally, our electronic search was limited to two databases and to papers written in English language, limiting the comprehensiveness of the review.

However, to our knowledge, this is the first study which attempts to map the characteristics of multicomponent interventions for fibromyalgia. In addition, performing this mapping review allowed us to create a comprehensive database of studies that can be used for further analyses and that is available upon request. We are persuaded that the integration of the various disciplines is a key factor for the treatment of such a condition. It is possible that the more the perspectives of the various professionals are integrated, the more the patients are able to comprehend the complexity of their syndrome and can be conscious about how the different biological, psychological, and social factors affect its course.

5. Conclusions

Multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary treatments must be considered as two ends of the same continuum. The degrees of integration of their component do not depend only on the juxtaposition or on the overlap between the various competences but rely on the possibility of tailoring the programs to the patients or on the presence of co-led sessions, team meetings, and a coordinate assessment. The various studies are very heterogeneous with regard to most of the variables described in our review. This diversity will need to be taken into account by future quantitative reviews of the literature.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Giorgio Cruccu for comments that greatly improved the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Smith H. S., Harris R., Clauw D. Fibromyalgia: an afferent processing disorder leading to a complex pain generalized syndrome. Pain Physician. 2011;14(2):E217–E245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahman A., Underwood M., Carnes D. Fibromyalgia. The British Medical Journal. 2014;348 doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1224.g1224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clauw D. J. Fibromyalgia and related conditions. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2015;90(5):680–692. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yunus M. B. Central sensitivity syndromes: a new paradigm and group nosology for fibromyalgia and overlapping conditions, and the related issue of disease versus illness. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2008;37(6):339–352. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cassisi G., Sarzi-Puttini P., Casale R., et al. Pain in fibromyalgia and related conditions. Reumatismo. 2014;66(1):72–86. doi: 10.4081/reumatismo.2014.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ablin J., Fitzcharles M. A., Buskila D., Shir Y., Sommer C., Häuser W. Treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome: recommendations of recent evidence-based interdisciplinary guidelines with special emphasis on complementary and alternative therapies. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013;2013:7. doi: 10.1155/2013/485272.485272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldenberg D. L. Management of fibromyalgia syndrome. Rheumatic Disease Clinics of North America. 1989;15(3):499–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldenberg D. L. Fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, and myofascial pain syndrome. Current Opinion in Rheumatology. 1997;9(2):135–143. doi: 10.1097/00002281-199703000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hauser W., Ablin J., Fitzcharles M. A., et al. Fibromyalgia. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2015;1 doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.22.15022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castelnuovo G., Giusti E. M., Manzoni G. M., et al. Psychological considerations in the assessment and treatment of pain in neurorehabilitation and psychological factors predictive of therapeutic response: evidence and recommendations from the italian consensus conference on pain in neurorehabilitation. Frontiers in Psychology. 2016;7:p. 468. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Papadopoulou D., Fassoulaki A., Tsoulas C., Siafaka I., Vadalouca A. A meta-analysis to determine the effect of pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments on fibromyalgia symptoms comprising OMERACT-10 response criteria. Clinical Rheumatology. 2016;35(3):573–586. doi: 10.1007/s10067-015-3144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scascighini L., Toma V., Dober-Spielmann S., Sprott H. Multidisciplinary treatment for chronic pain: a systematic review of interventions and outcomes. Rheumatology. 2008;47(5):670–678. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castelnuovo G., Giusti E. M., Manzoni G. M., et al. Psychological treatments and psychotherapies in the neurorehabilitation of pain: evidences and recommendations from the italian consensus conference on pain in neurorehabilitation. Frontiers in Psychology. 2016;7:p. 115. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nüesch E., Häuser W., Bernardy K., Barth J., Jüni P. Comparative efficacy of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions in fibromyalgia syndrome: network meta-analysis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2013;72(6):955–962. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tamburin S., Lacerenza M. R., Castelnuovo G., et al. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies in the integrated treatment of pain in neurorehabilitation. Evidence and recommendations from the italian consensus conference on pain in neurorehabilitation. European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. 2016;52(5):741–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fashler S. R., Cooper L. K., Oosenbrug E. D., et al. Systematic review of multidisciplinary chronic pain treatment facilities. Pain Research and Management. 2016;2016:19. doi: 10.1155/2016/5960987.5960987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peng P., Stinson J. N., Choiniere M., et al. Role of health care professionals in multidisciplinary pain treatment facilities in Canada. Pain Research & Management. 2008;13(6):484–488. doi: 10.1155/2008/726804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scott C. M., Hofmeyer A. T. Acknowledging complexity: critically analyzing context to understand interdisciplinary research. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2007;21(5):491–501. doi: 10.1080/13561820701605474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi B. C., Pak A. W. Multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity in health research, services, education and policy: 1. Definitions, objectives, and evidence of effectiveness. Clinical and Investigative Medicine. 2006;29(6):351–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hauser W., Bernardy K., Arnold B., Offenbacher M., Schiltenwolf M. Efficacy of multicomponent treatment in fibromyalgia syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Arthritis & Rheumatology. 2009;61(2):216–224. doi: 10.1002/art.24276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grant M. J., Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal. 2009;26(2):91–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.James K. L., Randall N. P., Haddaway N. R. A methodology for systematic mapping in environmental sciences. Environmental Evidence. 2016;5(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s13750-016-0059-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.SIGN. Methodology checklist 2: randomised controlled trials. http://www.sign.ac.uk/methodology/checklists.html. [DOI]

- 24.Downs S. H., Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–384. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Åkerblom S., Perrin S., Rivano Fischer M., McCracken L. M. The mediating role of acceptance in multidisciplinary cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain. The Journal of Pain. 2015;16(7):606–615. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amris K., Wæhrens E. E., Christensen R., Bliddal H., Danneskiold-Samsøe B. Interdisciplinary rehabilitation of patients with chronic widespread pain: primary endpoint of the randomized, nonblinded, parallel-group IMPROvE trial. Pain. 2014;155(7):1356–1364. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson F. J., Winkler A. E. Benefits of long-term fibromyalgia syndrome treatment with a multidisciplinary program. Journal of Musculoskeletal Pain. 2006;14(4):11–25. doi: 10.1300/J094v14n04_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Angst F., Brioschi R., Main C. J., Lehmann S., Aeschlimann A. Interdisciplinary rehabilitation in fibromyalgia and chronic back pain: a prospective outcome study. The Journal of Pain. 2006;7(11):807–815. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Angst F., Verra M. L., Lehmann S., Brioschi R., Aeschlimann A. Clinical effectiveness of an interdisciplinary pain management programme compared with standard inpatient rehabilitation in chronic pain: a naturalistic, prospective controlled cohort study. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2009;41(7):569–575. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bailey A., Starr L., Alderson M., Moreland J. A comparative evaluation of a fibromyalgia rehabilitation program. Arthritis Care and Research. 1999;12(5):336–340. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199910)12:5<336::AID-ART5>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bourgault P., Lacasse A., Marchand S., et al. Multicomponent interdisciplinary group intervention for self-management of fibromyalgia: a mixed-methods randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126324.0126324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carbonell-Baeza A., Aparicio V. A., Chillón P., Femia P., Delgado-Fernández M., Ruiz J. R. Effectiveness of multidisciplinary therapy on symptomatology and quality of life in women with fibromyalgia. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 2011;29(6, supplement 69):S97–S103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carbonell-Baeza A., Aparicio V. A., Ortega F. B., et al. Does a 3-month multidisciplinary intervention improve pain, body composition and physical fi tness in women with fibromyalgia? British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2011;45(15):1189–1195. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.070896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carbonell-Baeza A., Ruiz J. R., Aparicio V. A., et al. Multidisciplinary and biodanza intervention for the management of fibromyalgia. Acta Reumatologica Portuguesa. 2012;37(3):240–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Casanueva-Fernández B., Llorca J., Rubió J. B. I., Rodero-Fernández B., González-Gay M. A. Efficacy of a multidisciplinary treatment program in patients with severe fibromyalgia. Rheumatology International. 2012;32(8):2497–2502. doi: 10.1007/s00296-011-2045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castel A., Fontova R., Montull S., et al. Efficacy of a multidisciplinary fibromyalgia treatment adapted for women with low educational levels: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care & Research. 2013;65(3):421–431. doi: 10.1002/acr.21818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cedraschi C., Desmeules J., Rapiti E., et al. Fibromyalgia: a randomised, controlled trial of a treatment programme based on self management. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2004;63(3):290–296. doi: 10.1136/ard.2002.004945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Rooij A., Van Der Leeden M., Roorda L. D., Steultjens M. P. M., Dekker J. Predictors of outcome of multidisciplinary treatment in chronic widespread pain: an observational study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2013;14 doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-14-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gustafsson M., Ekholm J., Broman L. Effects of a multiprofessional rehabilitation programme for patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2002;34(3):119–127. doi: 10.1080/165019702753714147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hammond A., Freeman K. Community patient education and exercise for people with fibromyalgia: a parallel group randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2006;20(10):835–846. doi: 10.1177/0269215506072173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hamnes B., Mowinckel P., Kjeken I., Hagen K. B. Effects of a one week multidisciplinary inpatient self-management programme for patients with fibromyalgia: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2012;13 doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-13-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hooten W. M., Townsend C. O., Sletten C. D., Bruce B. K., Rome J. D. Treatment outcomes after multidisciplinary pain rehabilitation with analgesic medication withdrawal for patients with fibromyalgia. Pain Medicine. 2007;8(1):8–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hooten W. M., Townsend C. O., Decker P. A. Gender differences among patients with fibromyalgia undergoing multidisciplinary pain rehabilitation. Pain Medicine. 2007;8(8):624–632. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kas T., Colby M., Case M., Vaughn D. The effect of extremity strength training on fibromyalgia symptoms and disease impact in an existing multidisciplinary treatment program. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 2015;20(4):774–783. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Keel P. J., Bodoky C., Gerhard U., Müller W. Comparison of integrated group therapy and group relaxation training for fibromyalgia. Clinical Journal of Pain. 1998;14(3):232–238. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199809000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kroese M., Schulpen G., Bessems M., Nijhuis F., Severens J., Landewé R. The feasibility and efficacy of a multidisciplinary intervention with aftercare meetings for fibromyalgia. Clinical Rheumatology. 2009;28(8):923–929. doi: 10.1007/s10067-009-1176-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Eijk-Hustings Y., Kroese M., Tan F., Boonen A., Bessems-Beks M., Landewé R. Challenges in demonstrating the effectiveness of multidisciplinary treatment on quality of life, participation and health care utilisation in patients with fibromyalgia: a randomised controlled trial. Clinical Rheumatology. 2013;32(2):199–209. doi: 10.1007/s10067-012-2100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lemstra M., Olszynski W. P. The effectiveness of multidisciplinary rehabilitation in the treatment of fibromyalgia: A randomized controlled trial. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2005;21(2):166–174. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200503000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lera S., Gelman S. M., López M. J., et al. Multidisciplinary treatment of fibromyalgia: does cognitive behavior therapy increase the response to treatment? Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2009;67(5):433–441. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marcus D. A., Bernstein C. D., Haq A., Breuer P. Including a range of outcome targets offers a broader view of fibromyalgia treatment outcome: Results from a retrospective review of multidisciplinary treatment. Musculoskeletal Care. 2014;12(2):74–81. doi: 10.1002/msc.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martín J., Torre F., Padierna A., et al. Six-and 12-month follow-up of an interdisciplinary fibromyalgia treatment programme: results of a randomised trial. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 2012;30, supplement 74:S103–S111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martín J., Torre F., Aguirre U., et al. Evaluation of the interdisciplinary PSYMEPHY treatment on patients with fibromyalgia: a randomized control trial. Pain Medicine. 2014;15(4):682–691. doi: 10.1111/pme.12375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martín J., Torre F., Padierna A., et al. Impact of interdisciplinary treatment on physical and psychosocial parameters in patients with fibromyalgia: results of a randomised trial. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2014;68(5):618–627. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martín J., Torre F., Padierna A., et al. Interdisciplinary treatment of patients with fibromyalgia: improvement of their health-related quality of life. Pain Practice. 2014;14(8):721–731. doi: 10.1111/papr.12134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Martins M. R. I., Gritti C. C., dos Santos Junior R., et al. Randomized controlled trial of a therapeutic intervention group in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Revista Brasileira de Reumatologia. 2014;54(3):179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.rbre.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mengshoel A. M., Forseth K. Ø., Haugen M., Walle-Hansen R., Førre Ø. Multidisciplinary approach to fibromyalgia. A pilot study. Clinical Rheumatology. 1995;14(2):165–170. doi: 10.1007/BF02214937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Michalsen A., Li C., Kaiser K., et al. In-patient treatment of fibromyalgia: a controlled nonrandomized comparison of conventional medicine versus integrative medicine including fasting therapy. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013;2013:7. doi: 10.1155/2013/908610.908610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nielson W. R., Jensen M. P. Relationship between changes in coping and treatment outcome in patients with Fibromyalgia Syndrome. Pain. 2004;109(3):233–241. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Persson E., Lexell J., Eklund M., Rivano-Fischer M. Positive effects of a musculoskeletal pain rehabilitation program regardless of pain duration or diagnosis. PM and R. 2012;4(5):355–366. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ripley S., Ronzio C. R., Cozad C., et al. Evaluation of a multidisciplinary rehabilitation program for fibromyalgia: a pilot study. Today's Therapeutic Trends. 2003;21(2):159–184. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Romeyke T., Scheuer H. C., Stummer H. Fibromyalgia with severe forms of progression in a multidisciplinary therapy setting with emphasis on hyperthermia therapy—a prospective controlled study. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2014;10:69–79. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S74949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Salgueiro M., Basogain X., Collado A., et al. An artificial neural network approach for predicting functional outcome in fibromyalgia syndrome after multidisciplinary pain program. Pain Medicine. 2013;14(10):1450–1460. doi: 10.1111/pme.12185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Saral I., Sindel D., Esmaeilzadeh S., Sertel-Berk H. O., Oral A. The effects of long- and short-term interdisciplinary treatment approaches in women with fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. Rheumatology International. 2016;36(10):1379–1389. doi: 10.1007/s00296-016-3473-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stein K. F., Miclescu A. Effectiveness of multidisciplinary rehabilitation treatment for patients with chronic pain in a primary health care unit. Scandinavian Journal of Pain. 2013;4(4):190–197. doi: 10.1016/j.sjpain.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Suman A. L., Biagli B., Biasi G., et al. One-year efficacy of a 3-week intensive multidisciplinary non-pharmacological treatment program fibromyalgia patients. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 2009;27(1):7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Turk D. C., Okifuji A., Sinclair J. D., Starz T. W. Interdisciplinary treatment for fibromyalgia syndrome: clinical and statistical significance. Arthritis Care and Research. 1998;11(3):186–195. doi: 10.1002/art.1790110306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Van Koulil S., Van Lankveld W., Kraaimaat F. W., et al. Tailored cognitive-behavioural therapy and exercise training improves the physical fitness of patients with fibromyalgia. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2011;70(12):2131–2133. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.148577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.van Wilgen C. P., Bloten H., Oeseburg B. Results of a multidisciplinary program for patients with fibromyalgia implemented in the primary care. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2007;29(15):1207–1213. doi: 10.1080/09638280600949860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wennemer H. K., Borg-Stein J., Gomba L., et al. Functionally oriented rehabilitation program for patients with fibromyalgia: preliminary results. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2006;85(8):659–666. doi: 10.1097/01.phm.0000228677.46845.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Worrel L. M., Krahn L. E., Sletten C. D., Pond G. R. Treating fibromyalgia with a brief interdisciplinary program: Initial outcomes and predictors of response. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2001;76(4):384–390. doi: 10.4065/76.4.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pfeiffer A., Thompson J. M., Nelson A., et al. Effects of a 1.5-day multidisciplinary outpatient treatment program for fibromyalgia: a pilot study. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2003;82(3):186–191. doi: 10.1097/00002060-200303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oh T. H., Stueve M. H., Hoskin T. L., et al. Brief interdisciplinary treatment program for fibromyalgia: six to twelve months outcome. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2010;89(2):115–124. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181c9d817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vincent A., Whipple M. O., Oh T. H., Guderian J. A., Barton D. L., Luedtke C. A. Early experience with a brief, multimodal, multidisciplinary treatment program for fibromyalgia. Pain Management Nursing. 2013;14(4):228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Townsend C. O., Kerkvliet J. L., Bruce B. K., et al. A longitudinal study of the efficacy of a comprehensive pain rehabilitation program with opioid withdrawal: comparison of treatment outcomes based on opioid use status at admission. Pain. 2008;140(1):177–189. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gordon R. M., Corcoran J. R., Bartley-Daniele P., Sklenar D., Sutton P. R., Cartwright F. A transdisciplinary team approach to pain management in inpatient health care settings. Pain Management Nursing. 2014;15(1):426–435. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stanos S., Houle T. T. Multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary management of chronic pain. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America. 2006;17(2):435–450. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Karjalainen K., Malmivaara A., van Tulder M., et al. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for fibromyalgia and musculoskeletal pain in working age adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2000;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001984.CD001984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Momsen A.-M., Rasmussen J. O., Nielsen C. V., Iversen M. D., Lund H. Multidisciplinary team care in rehabilitation: an overview of reviews. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2012;44(11):901–912. doi: 10.2340/16501977-1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]