Abstract

Background

Diarrhea is a serious public health problem in Ethiopia. It is responsible for 24–30% of all infant deaths and there is a lack of evidence on the health burdens among the nomadic people. This study was therefore designed to assess the prevalence of diarrhea among children less thanvtwo year’s of age and its association with feeding practices among the nomadic people in Hadaleala district, northeast Ethiopia.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted in Hadaleala district. A total of 367 children less than two years of age were included using the multistage cluster sampling technique. Data were collected by a structured questionnaire. Multivariable binary logistic regression analysis was used to identify variables associated with diarrheal disease.

Results

The prevalence of diarrhea among children less than two year’s of age during the two week period was 31.3% (95% CI, 25.9, 36.1%). Diarrhea occurrence was associated with; children aged between 6–11 months (AOR 6.28, 95% CI, 3.00, 13.12), aged between 12–24 months (AOR 6.21, 95% CI, 3.13, 12.30), illiterate mothers (AOR 6.61, 95% CI, 2.27, 19.21), delay to initiate early breastfeeding for children aged less than six months (AOR 9.13, 95% CI, 1.78, 46.72), children less than six months of age not currently exclusively breastfed (AOR 13.33, 95% CI, 1.59, 112.12), delay to initiate early breastfeeding for children aged 6–24 months (AOR 2.87, 95% CI, 1.49, 5.51), no breastfeeding at the time of the survey (AOR 3.51, 95% CI, 1.57, 7.82), children aged 6–24 months who didn’t exclusively breastfeed in the first six months (AOR 19.24, 95% CI, 8.26, 44.82), consuming uncooked foods (AOR 6.99, 95% CI, 2.89, 16.92), not eating cooked foods immediately after cooking (AOR 3.74, 95% CI, 1.48, 9.45), hand washing with only water (AOR 24.94, 95% CI, 6.68, 93.12), and rotavirus vaccination (AOR 0.09, 95% CI, 0.03, 0.29).

Conclusions

The prevalence of diarrhea among children less than two year’s of age in Hadaleala district was high. To prevent diarrhea, the mothers should start breastfeeding early and practice exclusive breastfeeding. Moreover, mothers should improve the hygiene of supplementary foods.

Keywords: Childhood diarrhea, Less than two years of age, Child feeding practices, Nomads, Afar Region

Background

Diarrhea is a leading cause of child deaths, accounting for 9% of all deaths among children less than five years of age worldwide in 2015. This translates into over 1,400 young children dying each day, or about 530,000 children a year. Most deaths from diarrhea occur among children less than two years of age in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa [1–3].

Diarrheal disease is a serious public health problem among children in Ethiopia. In Ethiopia, during 2011, about 13% of children less than five years of age had diarrhea [4]. In the country, 24–30% of all infant deaths were due to diarrhea [5]. A multiregional baseline household health status survey indicated that the two week prevalence of any diarrhea among children aged 0–23 months was reported to be 22% [6]. As a part of the country, Afar region is one of the poorest, least developed and under-serviced regions of Ethiopia where the highest child mortality rate is reported. Rural communities of the region are suffering from shortage of water, hygiene and sanitation facilities. The main sources of water for the community are rivers, streams, ponds, and wells. During 2015, safe water and sanitation coverage of the district was 35% and 12%, respectively [7].

Childhood diarrheal disease among less than two year aged children is a result of the interactions of many factors; socioeconomic, environmental, behavioral factors, and child feeding practices. Literature show that child feeding practices had a direct link with childhood diarrhea. Early breastfeeding initiation, maintenance of breastfeeding, complementary feeding, time to the start of complementary feeding, hygiene of complementary foods, and child vaccination were some of the practices associated with childhood diarrhea. Colostrum or breast milk, which is rich in nutrients, has benefits to minimize infectious diseases, primarily acute diarrhea [8, 9]. Early initiation and maintenance of breastfeeding is the most appropriate form of nourishment for ensuring adequate growth and immunologic development of children. Breast milk provides all essential nutrients that are important for brain, nervous system, intellectual, neurological, psychomotor, and social development of children. It reduces the risk of infections and their associated mortality and morbidity [10–17]. Childhood diarrhea is a serious public health challenge among children who started complementary feeding. The hygiene of complementary foods is a risk factor associated with complementary feeding and unhygienically prepared and handled complementary foods may contain disease causing pathogenic microorganisms [18–25].

The health burdens of diarrheal disease among children less than two years of age are widely recognized at global level. Despite the fact that, its prevalence and the association with feeding practices among the nomadic people of Ethiopia are not well researched, and there is a lack of evidence among the nomadic people. This community based cross-sectional study was therefore designed to assess the prevalence of diarrheal disease in children aged less than two years and its association with child feeding practices among nomadic people in Hadaleala district, Afar Region, northeast Ethiopia. The results of this study will help the community to design and implement strategies to prevent or minimize childhood diarrheal disease. Furthermore, it may also fill the literature gaps and may act as a baseline data for further studies.

Methods

Study design and settings

A community based cross-sectional study was conducted in Hadaleala district, Afar Region, northeast Ethiopia in May, 2015. Hadaleala district is one of the districts of Hariresu zone, Afar Regional State. It is located at 341 km southwest of the regional capital, Semera, and 268 km north of Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. It has an area of 1272 km2 divided into 11 rural kebeles (the smallest administrative units in Ethiopia) with a total population of 42,845 as projected for the year 2015. It has 7,516 households with an average household size of 5.7 persons per house. The number of children aged less than five years account for 10.1% (4,328) of the total population. The population is very scattered, and the average population density is 14 persons/km2. The economy of the district is based on livestock and crop production [7] and due to the dispersed pasture and water resources, the communities in the district are mobile or nomadic.

Sampling size determination and procedure

The multistage cluster sampling technique was used to select study participants from the nomadic population. The clusters were villages with defined geographical boundaries. Out of a total of 11 kebeles, six were selected by the simple random sampling technique. The six selected kebeles were clustered into 39 villages, and 17 were selected by the systematic random sampling technique. The sampled kebeles and villages were nearly 55% and 44%, respectively, which is representative to the source population. Hence, the sampling procedure is multistage cluster sampling, all households (367) with children less than two years of age were included in the study.

Measurement of outcome variable

Diarrheal disease among children less than two years of age, the primary outcome variable of this study, is defined as having three or more loose or watery stools in 24 hours [26, 27]. The prevalence of childhood diarrheal disease within the two week period prior to data collection was calculated as the total number of diarrhea cases divided by 367 (the total number of children aged less than two years of age who were participating in the study).

Data collection tools and procedures

A pretested structured questionnaire was used to collect data. The questionnaire was prepared in English and translated to the local language and back translated to English to maintain the consistency of the questions. The tool was pre-tested out of the study area in a community which had similar characteristics prior to the actual data collection. To improve the quality of the data, eight diploma graduate nurses and two environmental health officers who were fluent enough, both in Amharic and Afarigna (local languages) and working in the district were involved in the data collection process. After the pretest and training, the data collectors visited all households in the selected clusters. The youngest (at the time of the survey) children were included in the study when there were more than one child aged less than two years of age in the household. Finally, the collected data were checked and corrected by the data collectors immediately after finalizing the questionnaire. Supervisors daily checked the completeness, quality, and consistency of information collected.

Data management and statistical analysis

Data were entered using the Epi-Info version 3.5.3 statistical package and exported to SPSS version 20 for further analysis. For most variables, data were presented by frequencies and percentages. The univariable binary logistic regression analysis was used to choose variables for the multivariable binary logistic regression analysis and variables which had less than 0.2 p – values by the univariable analysis were then separately analyzed by the multivariable binary logistic regression for controlling the possible effects of confounders. Variables which have significant associations were identified on the basis of the adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with a 95% confidence interval and p < 0.05. Normality and Hosmer and Lemshow test were done to assure the normal distribution of continuous variables and to check out the model fitness, respectively.

Results

Socioeconomic characteristics of respondents

A total of 367 mothers-children pairs had participated in the study with a 100% response rate. The median age of the children was 11 months, and the interquartile range (IQR) was 5–17 months. Only 14 (3.8%) of the households had three children. One hundred ninety-four (52.9%) of the children were male, and 158 (43.1%) of the children were aged between 12–24 months. Nearly half, 182 (49.6%) of the mothers were aged between 25–34 years. The mean age of the mothers was 27.6 years (with ± 6.0 standard deviation). Almost all, 360 (98.1%) of the mothers were currently married. The great majority, 321 (87.5%) of mothers had no formal education. Two hundred twenty (59.9%) of the households had more than five family members. About 258 (70.3%) households were economically poor (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socioeconomic information of households with children less than –two years of age (n = 367) in Hadaleala District, Afar Region, Northeast Ethiopia, May, 2015

| Variables | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Number of children less than two years of age in the house | ||

| One | 212 | 57.8 |

| Two | 141 | 38.4 |

| Three | 14 | 3.8 |

| Age of children (months) | ||

| < 6 | 113 | 30.8 |

| 6–11 | 96 | 26.2 |

| 12–24 | 158 | 43.1 |

| Sex of children | ||

| Male | 194 | 52.9 |

| Female | 173 | 47.1 |

| Age of mothers (years) | ||

| 15–24 | 126 | 34.3 |

| 25–34 | 182 | 49.6 |

| ≥ 35 | 59 | 16.1 |

| Marital status of mothers | ||

| Currently married | 360 | 98.1 |

| Not currently married | 7 | 1.9 |

| Educational status of mothers | ||

| No formal education | 321 | 87.5 |

| Formal education | 46 | 12.5 |

| Family size | ||

| ≥ 5 | 220 | 59.9 |

| < 5 | 147 | 40.1 |

| Economic status of households | ||

| Poor | 258 | 70.3 |

| Medium | 109 | 29.7 |

Child feeding practices

The status of breastfeeding of children less than two years of age was determined by this survey. All the children aged less than six months (n = 113) were fed breast milk at the time of the survey. However, 48 (42.5%) of the children did not feed breast milk exclusively, and also received complementary foods. One-third, 38 (33.6%), of the children didn’t receive breast milk within one hour immediately after birth.

Similarly, the breastfeeding status of children aged 6–24 months was determined. From a total of 254 children, 188 (74.0%) were fed breast milk exclusively for the first six months. On the other hand, only 47 (18.5%) of the children aged between 6–24 months were not being breastfed at the time of the survey. One hundred fifty-four (60.6%) children received breast milk within one hour immediately after birth.

About half, 131 (50.6%) of children aged less than two years, who started complementary feeding were given uncooked foods, like raw milk and nearly three–fourth, 191 (73.8%) of them have been given foods immediately after cooking. One hundred nineteen (32.4%) households who had children aged less than two years fetched drinking water from protected sources. More than half, 208 (56.7%) of the mothers have been washing their hands with water only before preparing child meal and feeding their children. Nearly one-third, 115 (31.3%) of the children received rotavirus vaccine (Table 2).

Table 2.

Child feeding practices of households (n = 367) in Hadaleala District, Afar Region, Northeast Ethiopia, May, 2015

| Variables | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Children who ate uncooked food (n = 259) | 131 | 50.6 |

| Children who ate cooked foods immediately (n = 259) | 191 | 73.8 |

| Children who received rotavirus vaccination (n = 367) | 115 | 31.3 |

| Mothers who washed their hands before food preparation and feeding the child with only water (n = 367) | 208 | 56.7 |

| Mothers who washed their hands before food preparation and feeding the child with soap (n = 367) | 159 | 43.3 |

| Drinking water sources (n = 367) | ||

| Protected | 119 | 32.4 |

| Unprotected | 248 | 67.6 |

Prevalence of diarrheal disease among less than two years of age children

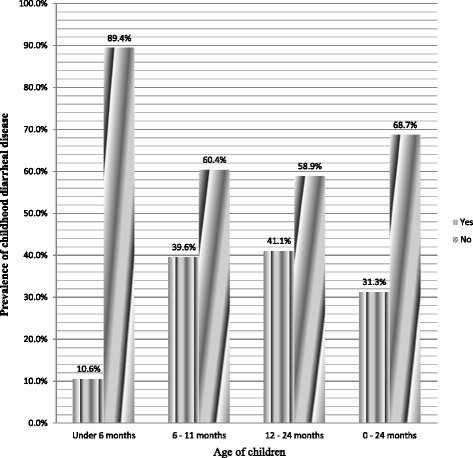

A total of 115 children less than two years of age had diarrhea in the two week period prior to data collection. Therefore, the two week period prevalence of diarrhea among children less than two years of age was found to be 31.3% (95% CI, 25.9, 36.1%). In addition, 58 children had diarrhea at the time of data collection, therefore, the point prevalence was found to be 15.8% (95% CI, 12.3, 19.7%). Nearly half, 57 (49.6%) of the children who had diarrhea obtained treatment from public health facilities and 58 (50.4%) were treated at home. The age specific prevalence of diarrhea was highest among children aged 12–24 months, at 65 (41.1%) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of diarrhea disease in different age categories of children less than two years of age in Hadaleala district, Afar Region, Northeast Ethiopia, May 2015

Factors associated with childhood diarrheal disease

Sociodemographic variables like age of children, sex of children, education status of mothers, marital status of mothers, family size, number of children less than two years of age, age of mothers, and household economic status were analyzed by Univariable binary logistic regression to identify the variables associated with childhood diarrheal disease among children less two years of age. Only a child’s age and mother’s education level had a p – value less than 0.20 and were further analyzed by the multivariable binary logistic regression model, and both of them were statistically associated with childhood diarrhea (Table 3). Children aged 6–11 months were 6.28 times more likely to be affected by diarrheal disease compared with children aged less than six months (AOR 6.28, 95% CI, 3.00, 13.12). Similarly, the likelihood of diarrheal disease was 6.21 times more likely to be higher among children aged between 12–24 months (AOR 6.21, 95% CI, 3.13, 12.30). The occurrence of diarrheal disease among children less than two years of age was 6.61 times higher when their mothers had no formal education compared with their counterparts (AOR 6.61, 95% CI, 2.27, 19.21).

Table 3.

Sociodemographic variables associated with diarrheal disease among children less than two years age (n = 367) in Hadaleala District, Afar Region, Northeast Ethiopia, May, 2015

| Socioeconomic variables | Diarrheal disease | Crude Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Age of children (months) | ||||

| < 6 | 12 (10.6%) | 101 (89.4%) | 1 | |

| 6–11 | 38 (39.6%) | 58 (60.4%) | 5.51 (2.67, 11.39) | 6.28 (3.00, 13.12)** |

| 12–24 | 65 (41.1%) | 93 (58.9%) | 5.88 (2.99, 11.58) | 6.21 (3.13, 12.30)** |

| Mothers’ education level | ||||

| No formal education | 111 (34.6%) | 210 (65.4%) | 5.55 (1.94, 15.88) | 6.61 (2.27, 19.21)* |

| Formal education | 4 (8.7%) | 42 (91.3%) | 1 | |

*Statistically significant variables at p = 0.001 **Statistically significant variables at p < 0.001

The result of Hosmer and Lemshow test was > 0.857

Early initiation of breastfeeding and child feeding status (whether exclusively breastfed or not) were entered into the binary logistic regression model and found to be associated with diarrheal disease among children aged less than six months (Table 4). Children who didn’t start breastfeeding within one hour immediately after birth had a greater chance to develop diarrheal disease (AOR 9.13, 95% CI, 1.78, 46.72). The likelihood of diarrhea was 13.33 times higher among children who didn’t exclusively receive breast milk compared with children who received breast milk exclusively (AOR 13.33, 95% CI, 1.59, 112.12).

Table 4.

The association between child feeding practices and diarrheal disease among children less than 6 months of age (n = 113) in Hadaleala District, Afar Region, Northeast Ethiopia, May, 2015

| Breastfeeding variables | Diarrheal disease | Crude Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Early breastfeeding initiation | ||||

| Yes | 2 (2.7%) | 73 (97.3%) | 1 | |

| No | 10 (26.3%) | 28 (73.7%) | 13.04 (2.69, 63.25) | 9.13 (1.78, 46.72)** |

| Breastfeeding status | ||||

| Not exclusive breastfeeding | 11 (22.9%) | 37 (77.1%) | 19.03 (2.36,153.33) | 13.33 (1.59, 112.12)* |

| Exclusive breastfeeding | 1 (1.5%) | 64 (98.5%) | 1 | |

*Statistically significant variables at p < 0.05 **Statistically significant variables at p < 0.01

The result of Hosmer and Lemshow test was > 0.216

Similarly, initiation of early breastfeeding within one hour after birth, breastfeeding status at the time of the survey, and child feeding status in the first six months were also associated with diarrheal disease among children aged between 6–24 months (Table 5). Children aged between 6–24 months who didn’t start breastfeeding within one hour after birth were 2.87 times more likely to be affected by diarrheal disease compared with their counterparts (AOR 2.87, 95% CI, 1.49, 5.51). Also, when breastfeeding was not started immediately after birth, childhood diarrheal disease was 3.51 times higher among children who didn’t maintain breastfeeding at the time of the survey (AOR 3.51, 95% CI, 1.57, 7.82). Children aged between 6–24 months, who were not exclusively breastfed in the first six months, had a greater chance to have diarrhea (AOR 9.24, 95% CI, 8.26, 44.82).

Table 5.

The association between breastfeeding practices and diarrheal disease among children aged between 6–24 months (n = 254) in Hadaleala District, Afar Region, Northeast Ethiopia, May, 2015

| Breastfeeding variables | Diarrheal disease | Crude Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Early breastfeeding initiation | ||||

| Yes | 40 (26.0%) | 114 (74.0%) | 1 | |

| No | 63 (63.0%) | 37 (37.0%) | 4.85 (2.82, 8.35) | 2.87 (1.49, 5.51)* |

| Breastfeeding at the time of the survey | ||||

| Yes | 72 (34.8%) | 135 (65.2%) | 1 | |

| No | 31(66.0%) | 16 (34.0%) | 3.63 (1.86, 7.08) | 3.51 (1.57, 7.82)* |

| Breastfeeding status in the first 6 months | ||||

| Not exclusive breastfeeding | 58 (87.9%) | 8 (12.1%) | 23.04 (10.23, 51.87) | 19.24 (8.26, 44.82)** |

| Exclusive breastfeeding | 45 (23.9%) | 143 (76.1%) | 1 | |

*Statistically significant variables at p < 0.05 **Statistically significant variables at p < 0.01 | The result of Hosmer and Lemshow test was > 0.995

Finally, consumption of uncooked foods, eating foods immediately after cooking, hand washing before food preparation and feeding the child, child vaccination, and drinking water sources were analyzed by the Univariable binary logistic regression to choose for the multivariable binary logistic regression. Consumption of uncooked foods, eating foods immediately after cooking, hand washing practices, and child vaccination had a p – value less than 0.20 and then analyzed by the multivariable binary logistic regression and found to be associated with diarrheal disease among children less than two years of age (Table 6). Children who consumed uncooked foods were 6.99 times more likely to be affected by diarrheal disease (AOR 6.99, 95% CI, 2.89, 16.92). Childhood diarrheal disease among children who didn’t eat foods immediately after cooking was 3.74 times higher compared with their counterparts (AOR 3.74, 95% CI, 1.48, 9.45). Mother’s hand washing practice before food preparation and feeding the children was also associated with the occurrence of diarrhea. Childhood diarrhea was higher among children whose mothers washed their hands with water only before food preparation and feeding the children compared with mothers who washed with soap (AOR 24.94, 95% CI, 6.68, 93.12). Furthermore, childhood diarrhea was associated with rotavirus vaccination.Childhood diarrheal disease was reduced by 91% among children who received rotavirus vaccination (AOR 0.09, 95% CI, 0.03, 0.29).

Table 6.

Correlates of childhood diarrheal disease among children less than 2 years of age in Hadaleala District, Afar Region, Northeast Ethiopia, May, 2015

| Variables | Diarrheal disease | Crude Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Hand washing practice (n = 367) | ||||

| With water only | 112 (53.8%) | 96 (46.2%) | 60.67 (18.75, 196.35) | 24.94 (6.68, 93.12)** |

| With soap | 3 (1.9%) | 156 (98.1%) | 1 | |

| Serving uncooked foods (n = 259) | ||||

| Yes | 88 (67.2%) | 43 (32.8%) | 15.42 (8.05, 29.55) | 6.99 (2.89, 16.92)** |

| No | 15 (11.7%) | 113 (88.3%) | 1 | |

| Feeding cooked foods immediately after cooking (n = 259) | ||||

| Yes | 50 (26.2%) | 141 (73.8%) | 1 | |

| No | 53 (77.9%) | 15 (22.1%) | 9.96 (5.16, 19.24) | 3.74 (1.48, 9.45)* |

| Child received rotavirus vaccination (n = 367) | ||||

| Yes | 5 (4.3%) | 110 (95.7%) | 0.06 (0.02, 0.15) | 0.09 (0.03, 0.29)** |

| No | 110 (43.7%) | 142 (56.3%) | 1 | |

| Drinking water source cp | ||||

| Protected | 9 (7.6%) | 110 (92.4%) | 1 | |

| Unprotected | 106 (42.7%) | 142 (57.3%) | 9.12 (4.42, 18.83) | 1.55 (0.47, 5.12) |

*Statistically significant variables at p < 0.01, **Statistically significant variables at p < 0.001. The result of Hosmer and Lemshow test was > 0.974

Discussion

This study investigated the prevalence of diarrheal disease and child feeding practices among children less than two years of age in Hadaleala district. The two week period prevalence of diarrheal disease was 31.3% (95% CI 25.9, 36.1%). The prevalence seen in this study is higher than the national prevalence, which was 23–25% [4]. The magnitude of childhood diarrheal disease reported by this study is also higher than the prevalence reported in three different regions of Ethiopia; Tigray (17%), Amhara (18%) and Oromiya (25%) [6] and studies done in northeastern Brazil (22.9%) [28] and Saudi Arabia (24%) [29]. The high incidence in the current study might be attributed to the difference in the sociodemographic, environmental, and behavioral characteristics of households and the nomadic nature of the population. Nomads migrate from place to place in search of pasture and water. Having no permanent residential places, they may not have access to basic health care, water and sanitation services. Their main sources of water are rivers, streams, and wells which are prone to contamination. The nomads practice open defecation and their living environment is polluted with human excreta, the main risk factor for diarrheal disease, especially for the children who routinely play in the unhygienic environment. Moreover, the people suffer from illiteracy and poverty which effects their quality of life. All these phenomena are the direct risk factors for the high prevalence of childhood diarrheal diseases [7].

In this study, it was found that diarrheal disease was associated with age of the children. The odds of having diarrheal disease were higher among children aged 6–11 and 12–24 months compared to children aged less than six months. This may be due to the fact that children aged more than six months start crawling or walking which increases their exposure to infectious agents. Furthermore, when children aged less than six months start complementary feeding this may increase their exposure to different types of infections through contaminated food and water [30–36].

This study identified that childhood diarrheal disease was statistically associated with the educational status of mothers. Children whose mothers had attended formal education (primary and above) were less likely to develop diarrhea compared to children whose mothers who had not attended any formal education. Receiving an education may increase awareness or knowledge about the transmission and prevention methods of diarrhea, enhanceing household health and sanitation practices, and encourages changes in behavior at the household level [37–42].

In this study, we found that diarrheal disease was associated with early initiation and maintenance of breastfeeding. Diarrhea was more common among children who didn’t start breastfeeding within one hour immediately after birth and among children who didn’t maintain breastfeeding at the time of the survey. Other studies also reported similar findings with this study [19, 28, 43]. This might be due to the fact that children who didn’t start breastfeeding within one hour after birth and didn’t maintain breastfeeding may fail to get the benefits of colostrum, which is rich by minerals and vitamins. Breast milk decreases both the incidence and severity of infectious diseases, primarily acute diarrhea [8, 9]. Early initiation and maintenance of breastfeeding is also the most appropriate form of nourishment for ensuring adequate growth and immunologic development of children [10–13]. Breastfeeding confers short term and long term benefits [15]. It helps to protect children against a variety of acute and chronic disorders [16, 17].

The childhood diarrheal disease was statistically associated with feeding status of children in the first six months of age. The current study explored that those children who didn’t receive breast milk exclusively in the first six months had a greater chance to develop diarrhea. This can be explained by the fact that supplementary foods may increase the exposure of children to different types of diseases causing pathogenic microorganisms due to contamination of food and water with different wastes [36]. Contamination of supplementary foods is very common in developing countries due to contaminated water, poor personal hygiene, inadequate cleaning of eating utensils, and inadequate storage of foods after preparation. The effect of supplementary foods is also severe if supplementary feeding is started before six months of age. This finding is in line with World Health Organization findings [44, 45]. This might be due to the fact that early complementary feeding initiation increases the risks of food borne infections, especially in regions where sanitation conditions are poor. Early intake of supplementary foods reduces the intake of breast milk and as a consequence, infants receive fewer protective factors [46–48].

This community based cross-sectional study explored that breastfeeding status at the time of the survey was statistically associated with childhood diarrheal disease. Breastfeeding has an impact on child survival of all preventive interventions. Breast milk provides all of the nutrients, vitamins and minerals an infant needs for growth. Breast milk carries antibodies that help combat disease [10, 12, 14–16, 49–52].

This study illustrated that childhood diarrheal disease was statistically associated with hygiene of the complementary foods. Diarrheal disease was highly prevalent among children who received uncooked foods and among children who didn’t eat foods immediately after cooking. Diarrhea was also very common if mothers washed their hands with water only before child meal preparation and feeding of their children. This might be due to the fact that uncooked foods, stored foods, and unhygienic hands are potential risk factors for contamination of foods and children with infectious agents. Foods that are stored under unfavorable conditions are given to infants without being heated or are inadequately reheated, resulting in an increased intake of pathogenic germs. Proper cooking and frequent hand washing with soap can reduce the load of pathogens [18, 20, 21, 23, 25].

This study revealed that childhood diarrheal disease was associated with rotavirus vaccine. Children who have been vaccinated had lower odds to develop diarrhea. This may indicate that vaccines have excellent protective efficacy against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis [18, 53–56].

Limitation of the study

Even though, childhood diarrhea was properly defined by using the WHO diarrhea assessment tool, its occurrence was determined based on the reports of mothers, without the confirmation of physicians. Due to this phenomenon, the study might be affected by social desirability bias. However, strong efforts were made to minimize social desirability bias. However, female data collectors who were part of the community were recruited owning to their strong relationships with mothers so that could minimize the social desirability bias. The other limitation of the study was a scarcity of literature on nomads or a similar population, thus, the discussion was made on the basis of the findings of the general population.

Conclusion

The prevalence of childhood diarrheal disease among children less than two years of age in the nomadic community of Hadaleala district was high. This high prevalence of diarrheal disease was statistically associated with the age of the children, education status of mothers, initiation of early breastfeeding, maintenance of breastfeeding, taking supplementary foods, hygiene of supplementary foods, hand washing practices of mothers, and rotavirus vaccination. This implies that a single intervention may not be sufficient to prevent childhood diarrheal disease. Therefore, the mothers should start breastfeeding early, practice exclusive breastfeeding, improve their child feeding practices and the hygiene of supplementary foods to minimize childhood diarrheal disease.

Acknowledgment

The authors are pleased to acknowledge the data collectors, field supervisors, study participants, Hadaleala District Health Office, Afar Regional Health Bureau for their unreserved contributions to the success of this study. The authors would also like to extend their gratitude to Hadaleala district administrators for their facilitation.

Funding

The authors of this study didn’t receive funds from any funding organization. The cost of data collection tools and data collectors’ fee was covered by the student himself.

Availability of data and materials

Data will be made available upon requesting the primary author.

Authors’ contributions

All the authors actively participated during conception of the research issue, development of a research proposal, data collection, analysis and interpretation, and writing various parts of the research report. WW designed the study protocol and had supervised the quality of data. ZG analyzed the data and had written the manuscript. BDB revised the study protocol and manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

None of the authors have any competing interests in the manuscript.

Consent for publication

This manuscript does not contain any individual person’s data.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the University of Gondar and an official letter was submitted to the district administrators. There were no risks due to participation in this research project, and the collected data were used only for this research purpose. Verbal informed consent was obtained from the mothers. All the information collected from each household was treated with complete confidentiality. During data collection, oral rehydration solution and Zinc tablets with clear instructions were given to children who had diarrhea, and advice was given to mothers to take their children to a nearby health institution for further management.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- AOR

Adjusted odds ratio

- CF

Complementary feeding

- CI

Confidence interval

- COR

Crude odds ratio

- IQR

Interquartile range

- Km

Kilometer

- Km2

Kilometer square

- SPSS

Statistical package for social sciences

Contributor Information

Zemichael Gizaw, Email: zemichael12@gmail.com.

Wondwoson Woldu, Email: alexanderweldu@gmail.com.

Bikes Destaw Bitew, Email: bikesdestaw2004@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Salami LI. Factors influencing breastfeeding practices in Edo state, Nigeria. Afr J Food Agric Nutr Dev. 2006;6(2):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quinn VJ, Guyon AB, Schubert JW, Stone-Jiménez M, Hainsworth MD, Martin LH. Improving breastfeeding practices on a broad scale at the community level: success stories from Africa and Latin America. J Hum Lact. 2005;21(3):345–354. doi: 10.1177/0890334405278383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S, Perin J, Scott S, Lawn JE, Rudan I, Campbell H, Cibulskis R, Li M. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet. 2012;379(9832):2151–2161. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60560-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghwass MMA, Ahmed D. Prevalence and predictors of 6-month exclusive breastfeeding in a rural area in Egypt. Breastfeed Med. 2011;6(4):191–196. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2011.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rahman AE, Moinuddin M, Molla M, Worku A, Hurt L, Kirkwood B, Mohan SB, Mazumder S, Bhutta Z, Raza F. Childhood diarrhoeal deaths in seven low-and middle-income countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92(9):664–671. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.134809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egata G, Berhane Y, Worku A. Predictors of non-exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months among rural mothers in east Ethiopia: a community-based analytical cross-sectional study. Int Breastfeed J. 2013;8:8. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-8-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sonko A, Worku A. Prevalence and predictors of exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life among women in Halaba special woreda, Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ Region/SNNPR/, Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. Arch Public Health. 2015;73(1):53–64. doi: 10.1186/s13690-015-0098-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kramer MS, Guo T, Platt RW, Sevkovskaya Z, Dzikovich I, Collet J-P, Shapiro S, Chalmers B, Hodnett E, Vanilovich I. Infant growth and health outcomes associated with 3 compared with 6 mo of exclusive breastfeeding. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78(2):291–295. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhandari N, Bahl R, Mazumdar S, Martines J, Black RE, Bhan MK. Group omotIFS: Effect of community-based promotion of exclusive breastfeeding on diarrhoeal illness and growth: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361(9367):1418–1423. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13134-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bier J-AB, Oliver T, Ferguson A, Vohr BR. Human milk reduces outpatient upper respiratory symptoms in premature infants during their first year of life. J Perinatol. 2002;22(5):354–359. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7210742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singhal A, Farooqi IS, O’Rahilly S, Cole TJ, Fewtrell M, Lucas A. Early nutrition and leptin concentrations in later life. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75(6):993–999. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.6.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hylander MA, Strobino DM, Pezzullo JC, Dhanireddy R. Association of human milk feedings with a reduction in retinopathy of prematurity among very low birthweight infants. J Perinatol. 2001;21(6):356–362. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7210548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horwood L, Darlow B, Mogridge N. Breast milk feeding and cognitive ability at 7–8 years. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2001;84(1):F23–F27. doi: 10.1136/fn.84.1.F23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leung AK, Sauve RS. Breast is best for babies. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(7):1010–1019. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.León-Cava N, Lutter C, Ross J, Martin L. Quantifying the benefits of breastfeeding: a summary of the evidence. Pan American Health Organization, Washington DC: PAHO 2002. ISBN 92 75 12397 7. Available at http://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=5654%3A2011-cuantificacion-beneficios-lactancia-materna-resena-evidencia-2002&catid=3719%3Apublications&Itemid=4081&lang=en. Accessed Aug 2016.

- 16.Fewtrell M. The long-term benefits of having been breast-fed. Curr Paediatr. 2004;14(2):97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cupe.2003.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ethiopia: Hadaleala district Finance and economic development office annual report 2014, by Dawud Haji Alisadik and others, Hadaleala. Office of Finance and Economic Development Afar Region, Ethiopia, 2014. https://library.mcmaster.ca/govpubs/cite.

- 18.Agustina R, Sari TP, Satroamidjojo S, Bovee-Oudenhoven IM, Feskens EJ, Kok FJ. Association of food-hygiene practices and diarrhea prevalence among Indonesian young children from low socioeconomic urban areas. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:977. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohammed I, Nibret E, Kibret M, Abera B, Adal M. Prevalence of diarrhea causing protozoan infections and associated risk factors in diarrheic under five children in Bahir Dar town, northwest Ethiopia: pediatric clinic based study. Ethiop J Sci Technol. 2016;9(1):15–30. doi: 10.4314/ejst.v9i1.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luby SP, Agboatwalla M, Feikin DR, Painter J, Billhimer W, Altaf A, Hoekstra RM. Effect of handwashing on child health: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9481):225–233. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66912-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Curtis V, Cairncross S. Effect of washing hands with soap on diarrhoea risk in the community: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3(5):275–281. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00606-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Semba RD, de Pee S, Ricks MO, Sari M, Bloem MW. Diarrhea and fever as risk factors for anemia among children under age five living in urban slum areas of Indonesia. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12(1):62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takanashi K, Chonan Y, Quyen DT, Khan NC, Poudel KC, Jimba M. Survey of food-hygiene practices at home and childhood diarrhoea in Hanoi, Viet Nam. J Health Popul Nutr. 2009;27(5):602–611. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v27i5.3636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mannan SR, Rahman MA. Exploring the link between food-hygiene practices and diarrhoea among the children of garments worker mothers in dhaka. Anwer Khan Modern Medical College Journal. 2010;1(2):4–11. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luby SP, Halder AK, Huda T, Unicomb L, Johnston RB. The effect of handwashing at recommended times with water alone and with soap on child diarrhea in rural Bangladesh: an observational study. PLoS Med. 2011;8(6):e1001052. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neji OI, Nkemdilim CC, Ferdinand NF. Factors influencing the practice of exclusive breastfeeding among mothers in tertiary health facility in Calabar, Cross River State. Niger Am J Nurs Sci. 2015;4(1):16–21. doi: 10.11648/j.ajns.20150401.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Black RE, Morris SS, Bryce J. Where and why are 10 million children dying every year? Lancet. 2003;361(9376):2226–2234. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13779-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santos FS. Santos LHd, Saldan PC, Santos FCS, Leite AM, Mello DFd: Breastfeeding and acute diarrhea among children enrolled in the family health strategy. Texto & Contexto-Enfermagem. 2016;25(1):e0220015. doi: 10.1590/0104-070720160000220015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Häggkvist A-P, Brantsæter AL, Grjibovski AM, Helsing E, Meltzer HM, Haugen M. Prevalence of breast-feeding in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study and health service-related correlates of cessation of full breast-feeding. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(12):2076–2086. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010001771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mengistie B, Berhane Y, Worku A. Prevalence of diarrhea and associated risk factors among children under-five years of age in Eastern Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Open J Prev Med. 2013;3(7):446–453. doi: 10.4236/ojpm.2013.37060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dessalegn M, Kumie A, Tefera W. Predictors of under-five childhood diarrhea: Mecha District, West Gojam, Ethopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2011;25(3):192–200. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mihrete TS, Alemie GA, Teferra AS. Determinants of childhood diarrhea among underfive children in Benishangul Gumuz Regional State. North West Ethiop BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:102. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-14-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Victor R, Baines SK, Agho KE, Dibley MJ. Determinants of breastfeeding indicators among children less than 24 months of age in Tanzania: a secondary analysis of the 2010 Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1):e001529. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilunda C, Panza A. Factors associated with diarrhea among children less than 5 years old in Thailand: a secondary analysis of Thailand multiple indicator cluster survey 2006. J Health Res. 2009;23(suppl):17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Woldemicael G. Diarrhoeal morbidity among young children in Eritrea: environmental and socioeconomic determinants. J Health Popul Nutr. 2001;19(2):83–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dewey KG, Adu‐Afarwuah S. Systematic review of the efficacy and effectiveness of complementary feeding interventions in developing countries. Matern Child Nutr. 2008;4(s1):24–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2007.00124.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rahman A. Assessing income-wise household environmental conditions and disease profile in urban areas: Study of an Indian city. Epidemiology. 2005;16(5):S43–S44. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200509000-00099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohammed S, Tilahun M, Tamiru D. Morbidity and associated factors of diarrheal diseases among under five children in Arba-Minch district, Southern Ethiopia, 2012. Sci J Public Health. 2013;1(2):102–106. doi: 10.11648/j.sjph.20130102.19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anteneh A, Kumie A. Assessment of the impact of latrine utilization on diarrhoeal diseases in the rural community of Hulet Ejju Enessie Woreda, East Gojjam Zone, Amhara Region. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2010;24(2):110–118. doi: 10.4314/ejhd.v24i2.62959. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yilgwa C, Yilgwan G, Abok I. Domestic Water Sourcing and the Risk of Diarrhoea: a Cross-Sectional survey of a Periurban Community in Jos, Nigeria. Nig J Med. 2010;19(3):34–37. doi: 10.4314/njm.v19i3.60182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gebru T, Taha M, Kassahun W. Risk factors of diarrhoeal disease in under-five children among health extension model and non-model families in Sheko district rural community, Southwest Ethopia. Comp cross-sectional study BMC Public Health. 2014;14:395. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yilgwan CS, Okolo S. Prevalence of diarrhea disease and risk factors in Jos University Teaching Hospital. Nig Ann Afr Med. 2012;11(4):217–221. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.102852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kitaw D. Breast feeding initiation time and its impact on diarrheal disease and pneumonia in West Africa. J Public Health Epidemiol. 2015;7(12):352–359. doi: 10.5897/JPHE2015.0741. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.WHO. Strengthening action to improve feeding of infants and young children 6–23 months of age in nutrition and child health program. 2008. Geneva. Available at www.who.int/child_adolescent_health/documents/9789241597890/en. Accessed Aug 2016.

- 45.WHO. Breastfeeding promotion and support in a baby-friendly hospital. 2009. Geneva: Switzerland. Available at http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/bfhi_trainingcourse_s3/en/. Accessed Aug 2016.

- 46.Kimani-Murage EW, Madise NJ, Fotso J-C, Kyobutungi C, Mutua MK, Gitau TM, Yatich N. Patterns and determinants of breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices in urban informal settlements. Nairobi Kenya BMC Public Health. 2011;11:396. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lartey A, Manu A, Brown KH, Peerson JM, Dewey KG. A randomized, community-based trial of the effects of improved, centrally processed complementary foods on growth and micronutrient status of Ghanaian infants from 6 to 12 mo of age. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70(3):391–404. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.3.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.César JA, Victora CG, Barros FC, Santos IS, Flores JA. Impact of breast feeding on admission for pneumonia during postneonatal period in Brazil: nested case–control study. BMJ. 1999;318(7194):1316–1320. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7194.1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scientific Rationale: Benefits of Breastfeeding. 2012. Available at https://www.unicef.org/nutrition/files/Scientific_rationale_for_benefits_of_breasfteeding.pdf. Accessed 25 Sept 2016.

- 50.Stuebe A. The risks of not breastfeeding for mothers and infants. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2009;2(4):222–231. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Victora CG, Barros A. Effect of breastfeeding on infant and child mortality due to infectious diseases in less developed countries: a pooled analysis. Lancet. 2000;355(9202):451–455. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)82011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heinig MJ. Host defense benefits of breastfeeding for the infant: effect of breastfeeding duration and exclusivity. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2001;48(1):105–123. doi: 10.1016/S0031-3955(05)70288-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Madhi SA, Cunliffe NA, Steele D, Witte D, Kirsten M, Louw C, Ngwira B, Victor JC, Gillard PH, Cheuvart BB. Effect of human rotavirus vaccine on severe diarrhea in African infants. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(4):289–298. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vesikari T, Matson DO, Dennehy P, Van Damme P, Santosham M, Rodriguez Z, Dallas MJ, Heyse JF, Goveia MG, Black SB. Safety and efficacy of a pentavalent human–bovine (WC3) reassortant rotavirus vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(1):23–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ruiz-Palacios GM, Pérez-Schael I, Velázquez FR, Abate H, Breuer T, Clemens SC, Cheuvart B, Espinoza F, Gillard P, Innis BL. Safety and efficacy of an attenuated vaccine against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(1):11–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Araujo EC, Clemens SAC, Oliveira CS, Justino MCA, Rubio P, Gabbay YB. Silva VBd, Mascarenhas JD, Noronha VL, Clemens R: Safety, immunogenicity, and protective efficacy of two doses of RIX4414 live attenuated human rotavirus vaccine in healthy Brazilian infants. Jornal De Pediatria. 2007;83(3):217–224. doi: 10.2223/JPED.1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon requesting the primary author.