Abstract

Background and objectives

Hyperphosphatemia is common among recipients of maintenance dialysis and is associated with a higher risk of mortality and cardiovascular events. A large randomized trial is needed to determine whether lowering phosphate concentrations with binders improves patient-important outcomes. To inform such an effort we conducted a pilot randomized controlled trial.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We conducted a randomized controlled trial of prevalent hemodialysis recipients already receiving calcium carbonate as a phosphate binder at five Canadian centers between March 31, 2014 and October 2, 2014. Participants were randomly allocated to 26 weeks of an intensive phosphate goal of 2.33–4.66 mg/dl (0.75–1.50 mmol/L) or a liberalized target of 6.20–7.75 mg/dl (2.00–2.50 mmol/L) by titrating calcium carbonate using a dosing nomogram. The primary outcome was the difference in the change in serum phosphate from randomization to 26 weeks.

Results

Fifty-three participants were randomized to the intensive group and 51 to the liberalized group. The median (interquartile range) daily dose of elemental calcium at 26 weeks was 1800 (1275–3000) mg in the intensive group, and 0 (0–500) mg in the liberalized group. The mean (SD) serum phosphate at 26 weeks was 4.53 (1.12) mg/dl (1.46 [0.36] mmol/L) in the intensive group and 6.05 (1.40) mg/dl (1.95 [0.45] mmol/L) in the liberalized group. Phosphate concentration in the intensive group declined by 1.24 (95% confidence interval, 0.75 to 1.74) mg/dl (0.40 [95% confidence interval, 0.24 to 0.56] mmol/L) compared with the liberalized group. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in the risk of hypercalcemia, hypocalcemia, parathyroidectomy, or major vascular events.

Conclusions

It is feasible to achieve and maintain a difference in serum phosphate concentrations in hemodialysis recipients by titrating calcium carbonate. A large trial is needed to determine if targeting a lower serum phosphate concentration improves patient-important outcomes.

Keywords: Hemodialysis; phosphate binders; randomized controlled trials; Calcium Carbonate; Calcium, Dietary; Canada; Goals; Humans; Hypercalcemia; hyperphosphatemia; Hypocalcemia; Kidney Failure, Chronic; Nomograms; Parathyroidectomy; Phosphates; Pilots; Prevalence; Random Allocation; renal dialysis; renal insufficiency, chronic

Introduction

Hyperphosphatemia is common in chronic dialysis recipients and is associated with morbidity and mortality (1,2). As a result, the reduction of elevated serum phosphate concentrations toward the normal range is advocated in clinical practice guidelines and is a core component of the medical management of patients who receive maintenance dialysis (3,4). This is most commonly achieved through a combination of dietary restriction of phosphate-containing foods and the use of oral phosphate binders (5).

Despite widespread use of these strategies to reduce serum phosphate concentration, there is a paucity of clinical trial evidence to support the claim that serum phosphate lowering with binders reduces mortality or other patient-important outcomes (6–8). The relationship between the use of phosphate binders and mortality has been examined in well designed observational studies comprising large cohorts of incident dialysis recipients (9,10). After propensity score matching to maximally account for confounding, these studies yielded conflicting findings. Ultimately, the lack of definitive high-grade evidence for the efficacy of phosphate binding is concerning due to the potential toxicity of binders (11), their cost (12), and the pill burden which compromises quality of life (13).

We conducted a pilot, multicenter, randomized controlled trial to evaluate whether targeting a normal serum phosphate concentration as compared with a liberalized approach to phosphate binding was feasible.

Materials and Methods

We completed an open-label, allocation-concealed, parallel group, pragmatic randomized controlled trial of intensive versus liberalized phosphate control in patients with ESRD receiving chronic hemodialysis (Clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT01994733). Patients were recruited from five Canadian dialysis programs (University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta; London Health Sciences Centre, London, Ontario; St. Joseph’s Healthcare, Hamilton, Ontario; St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Ontario; and Queen Elizabeth II Hospital, Halifax, Nova Scotia). The Research Ethics Board at each institution approved the trial and all participants provided written consent. Patients were randomized in randomly permuted blocks of two and four and stratified by center using a secure web-based system. The Population Health Research Institute in Hamilton, Canada, served as the trial coordinating center.

Participants

We recruited men and women >18 years of age who were receiving conventional chronic hemodialysis (up to 4 sessions/wk, 3–5 h/session) for at least 90 days, had a most recent serum phosphate of 1.30–2.50 mmol/L, and were receiving a calcium-containing phosphate binder. We excluded individuals who met one or more of the following criteria: scheduled for a live donor kidney transplant in the next 26 weeks; planned switch to a hemodialysis schedule of >16 h/wk within the next 26 weeks; planned switch to peritoneal dialysis within the next 26 weeks; pregnancy; albumin-corrected serum calcium >2.60 mmol/L requiring reduction of the calcium carbonate dose in the 8 weeks before screening; those taking >3 g/d of elemental calcium at the time of screening; a history of calciphylaxis; enrollment in another clinical trial that would interfere with adherence to or the safety of an oral phosphate binder; or if the patient’s attending nephrologist believed a particular serum phosphate concentration goal or calcium dose was medically necessary.

Intervention

After randomization, the number of calcium carbonate tablets each participant was taking was increased to a maximum dose of 3 g elemental calcium per day in the intensive group or decreased to a minimum dose or no calcium carbonate in the liberalized group. Adjustments were made on the basis of the patient’s serum phosphate concentration at baseline, week 2, week 4, and then with each routine bloodwork (see Supplemental Tables 1 and 2 for calcium carbonate adjustment nomograms). Routine bloodwork was done every 6 weeks at three participating sites and every calendar month at the other two sites. A serum phosphate concentration of 2.33–4.66 mg/dl (0.75–1.50 mmol/L) was targeted in the intensive group, consistent with clinical practice guidelines that suggest serum phosphate normalization (4). In the liberalized group, a serum phosphate concentration of >6.20 mg/dl (2.00 mmol/L), but <7.75 mg/dl (2.50 mmol/L), was targeted.

Calcium carbonate was chosen as the binder to be escalated or reduced as it is the phosphate binder predominantly used in Canada. Participants were offered complimentary chewable (Tums Extra Strength containing 300 mg of elemental calcium/tablet) or nonchewable (500 mg elemental calcium/tablet) formulations of calcium carbonate on the basis of their personal preference.

Cointerventions

Hemodialysis time was to remain constant and below a total of 16 h/wk in the absence of medical necessity. All patients in the trial had access to a dietitian for advice regarding the ESRD diet. However, in the liberalized group, suggestions regarding dietary phosphate restriction were omitted unless serum phosphate exceeded 7.75 mg/dl (2.50 mmol/L). Clinicians were free to adjust dialysate calcium concentrations or add calcium between meals for hypocalcemia.

If albumin-adjusted serum calcium exceeded 10.43 mg/dl (2.60 mmol/L) on any blood draw, calcium carbonate was not escalated further regardless of the serum phosphate concentration. The total calcium dose was reduced by 50% if the albumin-adjusted calcium exceeded 10.83 mg/dl (2.70 mmol/L). If albumin-adjusted serum calcium was <8.02 mg/dl (2.00 mmol/L), the clinician was permitted to add calcium carbonate between meals or at bedtime (i.e., as a calcium supplement), and this was not counted in the total calcium dose that was administered as a phosphate binder. Serum intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH) was collected at intervals dictated by dialysis unit policy. Given the intercenter variability in assays used, iPTH was expressed as a multiple of the upper limit of normal at that facility. Clinicians were free to adjust any aspect of care other than calcium carbonate dose (i.e., introduction/escalation of activated vitamin D products, cinacalcet, parathyroidectomy) in response to hyperparathyroidism.

Follow-Up

Participants were followed for 26 weeks. Follow-up was censored if a patient died, unexpectedly switched to a hemodialysis regimen that delivered >16 h/wk of therapy, commenced peritoneal dialysis, or received a kidney transplant.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the difference in the baseline to week 26 (or last follow-up) serum phosphate concentration between the intensive and liberalized groups Secondary outcomes included the number of patients who successfully achieved the target serum phosphate concentration at week 26 on the basis of the group to which they were randomized (i.e., <4.66 mg/dl [1.50 mmol/L] in the intensive group and >6.20 mg/dl [2.00 mmol/L] in the liberalized group); treatment compliance as defined by taking the study medication at least 80% of the time by self-report; number of serious adverse events (i.e., defined as fatal events or those which cause or prolong hospitalization or result in significant discomfort or disability); number of hospitalizations for vascular reasons unrelated to dialysis access; proportion of patients with a vascular death or nonfatal vascular event; proportion of patients developing albumin-adjusted serum calcium >10.43 mg/dl (2.60 mmol/L); number of fractures; and number of patients developing calcific uremic arteriolopathy (i.e., calciphylaxis).

Sample Size

We recruited 104 patients to enable the detection of a serum phosphate difference of as small as 1.09 mg/dl (0.35 mmol/L) at 26 weeks with a power of 0.90 and a two-tailed P value of 0.05, assuming a standard deviation of 2.02 mg/dl (0.65 mmol/L) on the basis of historical laboratory values at some of the participating hospitals. We designed the trial on the basis of an intergroup serum phosphate difference of 1.09 mg/dl (0.35 mmol/L) as this increment in serum phosphate concentration was previously associated with an approximately 20% relative increase in mortality in a meta-analysis of observational data (1).

Statistical Analyses

All analyses followed the intention-to-treat principle. Comparisons between groups were made as the intensive serum phosphate control group relative to the liberalized group. The primary outcome was evaluated by comparing the mean difference between the baseline and week 26 serum phosphate concentrations between groups. For participants who did not have a serum phosphate measured at 26 weeks, the next closest measurement was used. A sensitivity analysis was conducted using all serum phosphate concentrations as repeated measures with a mixed effects linear regression model in which patients were considered random effects and the treatment group was considered a fixed effect. Outcomes expressed as frequencies (e.g., the composite of fatal and nonfatal vascular events) were analyzed by computing the relative risk between groups and the corresponding 95% confidence interval and P value using the Fisher exact test. Outcomes expressed as a count (i.e., number of serious adverse events, and number of hospitalizations for vascular reasons) were reported as discrete events and expressed as proportions. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant without adjustment for multiple comparisons. All analyses were conducted using SAS v 9.2 (Cary, NC).

Results

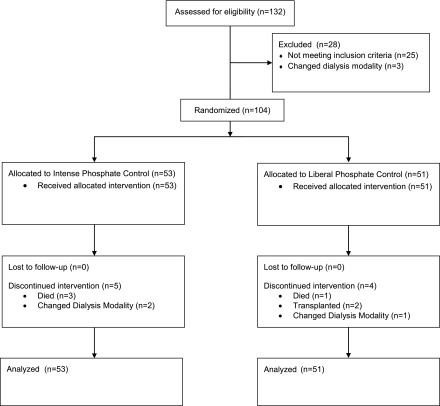

We recruited 104 patients between March 31, 2014 and October 2, 2014; 53 were randomized to intensive phosphate control and 51 to liberalized phosphate control. Mean age was 64.4 (SD 12.4) years and 34 (32.7%) were women. The median time on dialysis was 3.0 (interquartile range, 2.0–6.0) years and the most common cause of ESRD was diabetes. Nineteen patients (18.3%) had a prior myocardial infarction and 15 (14.4%) had a prior stroke. Patient characteristics were well balanced between the treatment groups at baseline (Table 1). Censoring before 26 weeks occurred in five intensive group participants (three deaths, two changes in dialysis modality) and four liberalized group participants (one death, two kidney transplants, one change in dialysis modality). Flow of patients through the trial is depicted in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by intervention group

| Characteristic | Liberalized, n=51 | Intensive, n=53 |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr (SD) | 62.4 (11.1) | 66.3 (13.3) |

| Women, n (%) | 19 (37.3) | 15 (28.3) |

| Primary reason of ESRD, n (%) | ||

| Diabetes | 26 (51.0) | 29 (54.7) |

| Hypertension/ischemic | 7 (13.7) | 10 (18.9) |

| GN | 7 (13.7) | 6 (11.3) |

| PCKD | 4 (7.8) | 2 (3.8) |

| Other | 7 (13.7) | 6 (11.3) |

| Time since commencing hemodialysis, yr (IQR) | 3 (1, 6) | 3 (2, 5) |

| Weekly time on hemodialysis, h (SD) | 11.7 (1.1) | 11.9 (1.6) |

| Urine output >1 cup/d, n (%) | 18 (35.3) | 20 (37.7) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||

| History of coronary artery disease | 15 (29.4) | 18 (34.0) |

| History of diabetes | 29 (56.9) | 35 (66.0) |

| History of stroke | 6 (11.8) | 9 (17.0) |

| Vascular disease | 8 (15.7) | 10 (18.9) |

| Bone-mineral metabolism medication use, n (%) | ||

| Sevelamer | 4 (7.8) | 5 (9.4) |

| Aluminum | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.9) |

| Alfacalcidol | 17 (33.3) | 23 (43.4) |

| Calcitriol | 9 (17.6) | 14 (26.4) |

| Ergocalciferol | 7 (13.7) | 9 (17.0) |

| Cholecalciferol | 7 (13.7) | 5 (9.4) |

| Cinacalcet | 1 (2.0) | 1 (1.9) |

| History of parathyroidectomy, n (%) | 5 (9.8) | 3 (5.7) |

| Serum phosphate concentration, mg/dl (SD) | 5.52 (0.93) | 5.27 (0.93) |

| mmol/L (SD) | 1.78 (0.30) | 1.70 (0.30) |

| Albumin-adjusted calcium concentration, mg/dl (SD) | 9.30 (0.80) | 9.46 (0.68) |

| mmol/L (SD) | 2.32 (0.20) | 2.36 (0.17) |

| Dialysate ionized calcium concentration mg/dl (IQR) | 5.01 (5.01, 5.01) | 5.01 (5.01, 5.01) |

| mmol/L (IQR) | 1.25 (1.25, 1.25) | 1.25 (1.25, 1.25) |

Continuous data are presented as mean (SD) or median (interquartile range), as appropriate. Categoric data are presented as number (%). Conversion factors: phosphate: 1mmol/L=3.10 mg/dl; calcium: 1mmol/L= 4.01 mg/dl. PCKD, polycystic kidney disease; IQR, interquartile range.

Figure 1.

Participant flow in the TARGET trial.

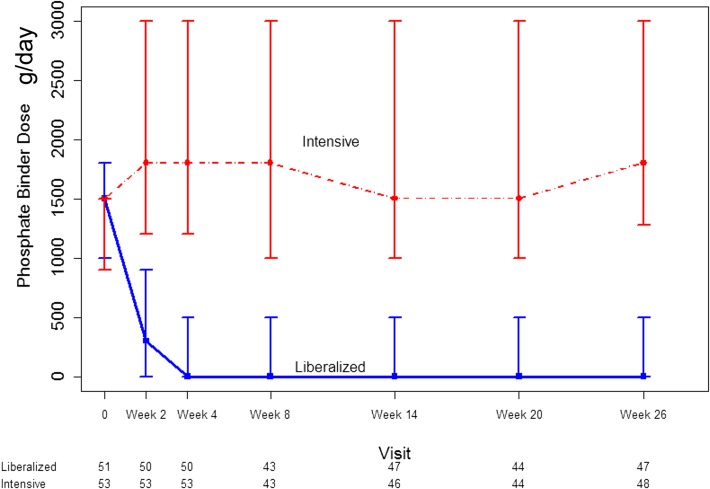

Phosphate Binder Dosing during the Follow-Up Period

Self-reported adherence to the trial-prescribed calcium carbonate dose was >90% at all study visits. The median daily calcium dose at randomization was 1500 (interquartile range [IQR], 900–1500) mg in the intensive group and 1500 (IQR, 1000–1800) mg in the liberalized group. By 26 weeks, the median daily calcium dose was 1800 (IQR, 1275–3000) mg in the intensive group and 0 (IQR, 0–500) mg in the liberalized group. The prescribed daily calcium dose over the course of follow-up is displayed in Figure 2. Depending on whether he/she chose a chewable or nonchewable form of calcium carbonate, a typical participant in the intensive arm received 4–6 additional tablets daily as compared with a patient in the liberalized arm.

Figure 2.

Sustained separation in the dose of elemental calcium administered as calcium carbonate in patients randomized to a liberalized phosphate target (>2.00 mmol/L) or an intensive serum phosphate target (0.75–1.00 mmol/L). Dots represent medians and whiskers represent 2.5th and 97.5th percentile. The numbers under the x-axis represent the number of participants under active follow-up and with evaluable data at each time point.

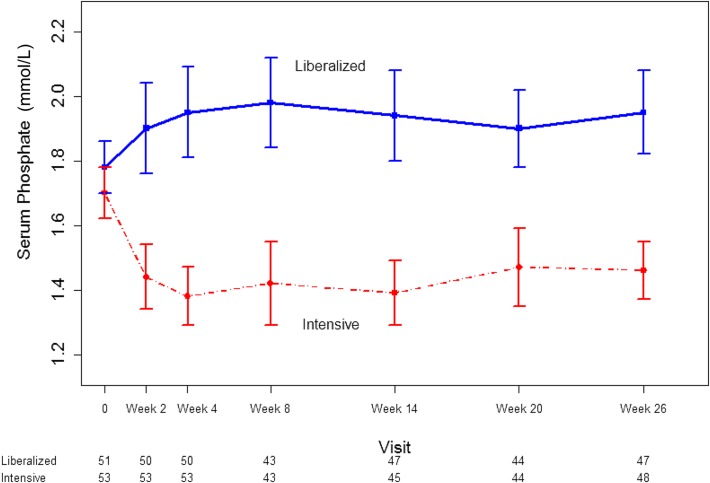

Phosphate Control during the Study Follow-Up Period

As shown in Figure 3, a separation in serum phosphate concentration was evident within the first 2 weeks after randomization. The phosphate concentration in the intensive group fell by a mean of 1.24 (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.74 to 1.74; P<0.001) mg/dl (0.40 mmol/L; 95% CI, 0.24 to 0.56 mmol/L) over the study as compared with the liberalized group. The repeated measures model estimated a serum phosphate concentration that was 1.46 (95% CI, 1.15 to 1.74) mg/dl (0.47 mmol/L; 95% CI, 0.37 to 0.56 mmol/L; P<0.001) lower in the intensive group compared with the liberalized group over the study duration. At the final study visit, 29 (54.7%) patients in the intensive group had a serum phosphate concentration of <4.66 mg/dl (1.50 mmol/L), whereas 14 (27.5%) patients in the liberalized group had a serum phosphate concentration of >6.20 mg/dl (2.00 mmol/L).

Figure 3.

Sustained separation in serum phosphate concentration in patients randomized to a liberalized serum phosphate target (>2.00 mmol/L) or an intensive serum phosphate target (0.75–1.00 mmol/L). Dots represent medians and whiskers represent 2.5th and 97.5th percentile. 1 mmol/L phosphate = 3.10 mg/dl. The numbers under the x-axis represent the number of participants under active follow-up and with evaluable data at each time point.

Hypophosphatemia (serum phosphate <2.33 mg/dl [0.75 mmol/L]) was noted in no patients in the intensive group and in 1 (2.0%) patient in the liberalized group. Significant hyperphosphatemia (serum phosphate >7.75 mg/dl [2.50 mmol/L]) occurred in 21(42.0%) patients in the liberalized group and 2 (3.8%) in the intensive group.

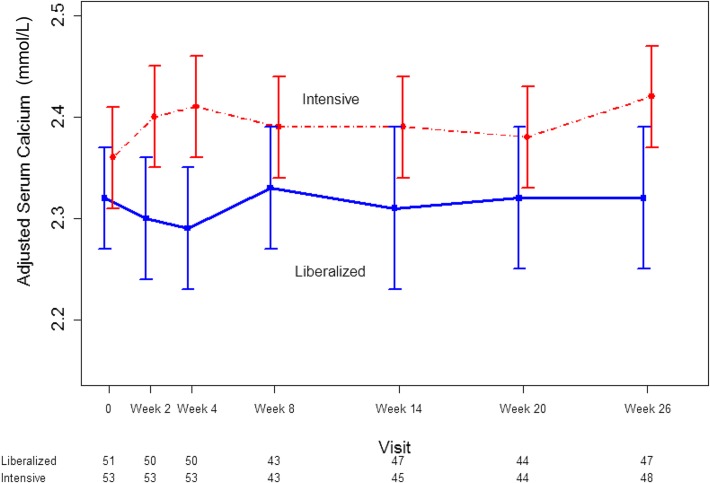

Phosphate Binding Strategy and Other Mineral Metabolic Parameters

Patients in the intensive group had slightly higher serum calcium concentrations than the liberal group over the course of the trial (Figure 4). At 26 weeks, albumin-adjusted serum calcium declined by 0.28 mg/dl (0.07 mmol/L) in the liberalized group as compared with the intensive group (95% CI, −0.60 to 0.04 mg/dl [−0.15 to 0.01 mmol/L]; P=0.11). In the intensive group, 11 (20.8%) patients had hypercalcemia that required a change in phosphate binder dose compared with 5 (9.8%) patients in the liberalized group (P=0.17). Hypocalcemia requiring the addition of calcium carbonate occurred in 4 (7.8%) patients in the liberalized group and no patients in the intensive group (P=0.05).

Figure 4.

Modest decline in albumin-adjusted serum calcium concentration in patients randomized to a liberalized serum phosphate target (>2.00 mmol/L) or an intensive serum phosphate target (0.75–1.00 mmol/L). Dots represent medians and whiskers represent 2.5th and 97.5th percentile. 1 mmol/L calcium = 4.01 mg/dL. The numbers under the x-axis represent the number of participants under active follow-up and with evaluable data at each time point.

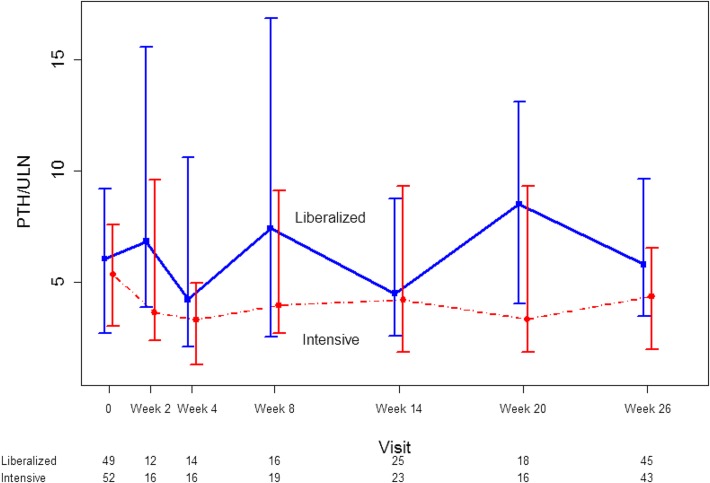

There was no intergroup difference in the change in iPTH, expressed in multiples of the upper limit of normal, from randomization to the end of follow-up (mean difference 1.14; 95% CI, −0.78 to 3.07; P=0.25) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Lack of difference in intact parathyroid hormone concentration in patients randomized to a liberalized serum phosphate target (>2.00 mmol/L) or an intensive serum phosphate target (0.75–1.00 mmol/L). Dots represent medians and whiskers represent 2.5th and 97.5th percentile. The numbers under the x-axis represent the number of participants under active follow-up and with evaluable data at each time point. ULN, upper limit of normal.

There was no meaningful change in the prescribed dialysate calcium concentration or in the dose of activated Vitamin D from randomization to the end of the trial.

Clinical Events and Quality of Life

Clinical events are summarized in Table 2 and no statistically significant differences were noted between the two groups. Over the 26-week follow-up period, there were four deaths (three in the intensive group and one in the liberalized group) and all were attributed to vascular causes. Health-related quality of life measured by the EuroQoL-5D feeling thermometer visual analog scale did not differ between groups (P=0.89) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Clinical outcomes by intervention group

| Outcome | Liberalized, n=51 | Intensive, n=53 | Relative Risk (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vascular death or vascular event | 3 (6) | 5 (9) | 0.62 (0.16 to 2.48) |

| Fracture | 3 (6) | 1 (2) | 3.12 (0.34 to 29.0) |

| Calciphylaxis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA |

| Parathyroidectomy | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 1.04 (0.07 to 16.2) |

| Hospitalization (all cause) | 18 (35) | 14 (26) | 1.34 (0.75 to 2.39) |

| Hospitalization for vascular reason | 5 (10) | 5 (9) | 1.04 (0.32 to 3.38) |

| Serious adverse event (not listed above) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA |

Data reported as number (%). 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; NA, not applicable.

Table 3.

Quality of life as measured with the EuroQoL-5D tool

| Variables | Liberalized | Intensive | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | ||

| Baseline EQ5D score | 50 | 66.84 (18.64) | 53 | 65.15 (17.87) | 0.64 |

| Week 26 EQ5D score | 45 | 64.02 (21.56) | 50 | 65.02 (18.58) | 0.81 |

| Week 26−baseline EQ5D score | 45 | −1.80 (20.57) | 50 | −1.24 (17.36) | 0.89 |

EQ5D, EuroQoL-5D survey tool.

Discussion

We demonstrated that randomly allocating hemodialysis recipients to two different serum phosphate concentration targets is feasible and results in a meaningful separation in serum phosphate concentration by varying calcium carbonate tablets alone. Moreover, this was achieved by completely withdrawing calcium carbonate in the majority of participants in the liberalized group and maintaining a dose of <2 g/d in patients in the intensive group.

Basic science experiments have implicated hyperphosphatemia as a mediator of vascular calcification (14–16). Moreover, a variety of observational studies have shown a relationship between high serum phosphate concentration and cardiovascular events, fractures, and all-cause mortality among chronic dialysis recipients (17–20). A meta-analysis of such studies showed that a 1 mg/dl increase in serum phosphate concentration was associated with an incremental increase of 18% in death (1). However, the causal relationship between hyperphosphatemia and mortality has never been demonstrated.

Serum phosphate control is a cornerstone of care in patients who receive maintenance dialysis. Contemporary guidelines recommend the control of serum phosphate concentration toward normal values which in most labs would be a value of <4.34–4.66 mg/dl (1.40–1.50 mmol/L) (4). Achievement of this target is often challenging for patients receiving conventional hemodialysis regimens. A conventional hemodialysis regimen of a 3–4-hour dialysis session thrice weekly will generally be inadequate to remove excess dietary phosphate, even when phosphate intake is moderated. The inevitable surfeit of phosphate necessitates the use of oral phosphate binders to avoid hyperphosphatemia. When administered with meals, such binders limit gastrointestinal absorption of phosphate and thus mitigate the tendency to hyperphosphatemia. Although nearly universally prescribed to patients receiving conventional dialysis regimens, the efficacy of phosphate binders in reducing adverse cardiovascular events and mortality has never been proven. This is despite the fact that phosphate binders are the chief contributors to the substantial pill burden of patients receiving hemodialysis and that each binder has its own set of proven and theoretical toxicities (13).

The ability of calcium salts to effectively bind intestinal phosphate and reduce serum phosphate concentration has been recognized for decades (3,21–23). In Canada, calcium-based phosphate binders, and calcium carbonate in particular, are the most frequently used binders in the dialysis population. Their efficacy and low cost, in addition to their ability to counter the hypocalcemia that is frequently seen in advanced CKD, have solidified this position for calcium-based binders. However, hypercalcemia, gastrointestinal intolerance, and the concern that calcium intake via phosphate binders might exacerbate vascular calcification have led to the development of noncalcium-based binders such as sevelamer, lanthanum, and ferric citrate (24–27). Although some of these products have gained popularity in certain jurisdictions, there is inadequate evidence that these agents, which are costlier than calcium-based binders, lead to improved clinical outcomes (28,29).

To our knowledge, this is the first trial to report on dialysis recipients randomly allocated to two different serum phosphate targets. Although several trials compared the relative efficacy of different types of phosphate binders on biochemical indices and, in a few cases, clinical endpoints, none have addressed the more fundamental question of whether serum phosphate lowering improves patient-important outcomes (24,25). Although this pilot trial was not intended to examine the effect of phosphate lowering on patient-important events, it demonstrates the feasibility and safety of performing a large clinical trial, powered to establish whether phosphate lowering reduces fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events. As such, our trial serves as a vital precursor for future work in this area. The fact that mean phosphate values generally remained below 6.20 mg/dl (2.00 mmol/L) in the liberalized group despite the withdrawal of all binders suggests that most patients enrolled in a trial will not become excessively hyperphosphatemic while completely off binders. One could therefore consider a simple strategy of binder intensification versus complete binder withdrawal (with rescue for extreme hyperphosphatemia) in a larger trial.

We established broad inclusion criteria that made the majority of prevalent hemodialysis recipients eligible. We are therefore confident that the trial’s findings, as well as its relevance to the design of future trials, are broadly applicable. To facilitate adherence and minimize disruption to participants, we adopted a pragmatic approach to titrating phosphate binder dosing. Most blood values used to determine ongoing calcium carbonate dosing were derived from routine predialysis bloodwork drawn as part of usual dialysis care. Because the results of such tests were available within a few hours, research staff were able to advise participants about subsequent dosing by the end of the same dialysis session and provide them with a resupply of calcium carbonate if needed. Finally, in order to prevent the theoretical risks attributed to excessive hyperphosphatemia, bloodwork was routinely monitored throughout the trial and patients received “rescue” phosphate binding for more extreme hyperphosphatemia.

The trial has some important limitations. We elected not to blind the phosphate-binding strategy, which may have made the trial more susceptible to differential cointerventions which could bias the results. Ultimately, we felt that blinding a medication titrated on the basis of ongoing routine bloodwork would be impracticable. Furthermore, part of the goal of a liberalized strategy was to reduce the patient’s pill burden to enhance quality of life, an effect that would be lost by the use of placebo. Despite good adherence, few participants were able to consistently meet their serum phosphate target. This is expected to some extent given the inherent variability of serum phosphate concentration in hemodialysis recipients, likely due to the sensitivity of this parameter to a variety of factors (e.g., abbreviated dialysis sessions, transient dietary changes, adherence to binders). Despite this, on average, there was a clear separation in serum phosphate concentration between the treatment groups that became evident shortly after randomization. This difference was sustained through week 26 with a magnitude that might reasonably be expected to result in important effects on survival. This pilot trial was of a relatively short duration and it is possible that the differences in serum phosphate concentration may not be sustainable in a multiyear study.

Our reliance on calcium carbonate for titration of serum phosphate may be a source of criticism. Recent meta-analyses of relatively small trials suggested that sevelamer confers superior outcomes to calcium-based binders (28–30). However, this evidence base is of low quality and calcium salts are still the most commonly used phosphate-lowering medications in many countries thanks to their efficacy in lowering phosphate, reasonable tolerance, and low cost. Our intent was to test whether a strategy of changing the dose of phosphate binders in patients who were already using them would result in a substantial difference in serum phosphate concentration. We anticipate future research can generalize our findings and permit the use of any available phosphate binders.

We demonstrated that randomizing hemodialysis recipients to a pragmatic strategy of targeting an intensive or liberalized serum phosphate concentration by manipulating oral phosphate binders is feasible and safe. A meaningful and sustained separation in phosphate concentration was achieved and, in most patients randomized to the liberalized arm, the withdrawal of all phosphate binders did not lead to excessive hyperphosphatemia. The continued widespread use of phosphate binders to achieve intensive serum phosphate targets despite the absence of evidence for the efficacy of this strategy is unacceptable. A large trial, powered for patient-important outcomes, is urgently needed.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors warmly appreciate the dedication of our patient participants and local research staff without whom this trial could not be completed. We are grateful for the support of the Canadian Nephrology Trials Network.

This work was funded by an operating grant provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. M.W. was supported by a New Investigator’s Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. A.X.G. was supported by the Dr. Adam Linton Chair in Kidney Health Analytics.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Getting Out of the Phosphate Bind: Trials to Guide Treatment Targets,” on pages 868–870.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.10941016/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Palmer SC, Hayen A, Macaskill P, Pellegrini F, Craig JC, Elder GJ, Strippoli GF: Serum levels of phosphorus, parathyroid hormone, and calcium and risks of death and cardiovascular disease in individuals with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 305: 1119–1127, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Block GA, Ix JH, Ketteler M, Martin KJ, Thadhani RI, Tonelli M, Wolf M, Jüppner H, Hruska K, Wheeler DC: Phosphate homeostasis in CKD: Report of a scientific symposium sponsored by the National Kidney Foundation. Am J Kidney Dis 62: 457–473, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Kidney Foundation : K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for bone metabolism and disease in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 42[Suppl 3]: S1–S201, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Work Group : KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of Chronic Kidney Disease-Mineral and Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl 76(113): S1–S130, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tonelli M, Pannu N, Manns B: Oral phosphate binders in patients with kidney failure. N Engl J Med 362: 1312–1324, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Navaneethan SD, Palmer SC, Vecchio M, Craig JC, Elder GJ, Strippoli GF: Phosphate binders for preventing and treating bone disease in chronic kidney disease patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD006023, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hutchison AJ: Novel phosphate binders: Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose. Kidney Int 86: 471–474, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palmer SC, Teixeira-Pinto A, Saglimbene V, Craig JC, Macaskill P, Tonelli M, de Berardis G, Ruospo M, Strippoli GF: Association of drug effects on serum parathyroid hormone, phosphorus, and calcium levels with mortality in CKD: A meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis 66: 962–971, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isakova T, Gutiérrez OM, Chang Y, Shah A, Tamez H, Smith K, Thadhani R, Wolf M: Phosphorus binders and survival on hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 388–396, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winkelmayer WC, Liu J, Kestenbaum B: Comparative effectiveness of calcium-containing phosphate binders in incident U.S. dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 175–183, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodman WG, Goldin J, Kuizon BD, Yoon C, Gales B, Sider D, Wang Y, Chung J, Emerick A, Greaser L, Elashoff RM, Salusky IB: Coronary-artery calcification in young adults with end-stage renal disease who are undergoing dialysis. N Engl J Med 342: 1478–1483, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manns B, Stevens L, Miskulin D, Owen WF Jr, Winkelmayer WC, Tonelli M: A systematic review of sevelamer in ESRD and an analysis of its potential economic impact in Canada and the United States. Kidney Int 66: 1239–1247, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiu YW, Teitelbaum I, Misra M, de Leon EM, Adzize T, Mehrotra R: Pill burden, adherence, hyperphosphatemia, and quality of life in maintenance dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1089–1096, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moe SM, Chen NX: Pathophysiology of vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease. Circ Res 95: 560–567, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moe SM: Vascular calcification: Hardening of the evidence. Kidney Int 70: 1535–1537, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giachelli CM: The emerging role of phosphate in vascular calcification. Kidney Int 75: 890–897, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Block GA, Hulbert-Shearon TE, Levin NW, Port FK: Association of serum phosphorus and calcium x phosphate product with mortality risk in chronic hemodialysis patients: A national study. Am J Kidney Dis 31: 607–617, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Block GA, Klassen PS, Lazarus JM, Ofsthun N, Lowrie EG, Chertow GM: Mineral metabolism, mortality, and morbidity in maintenance hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 2208–2218, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kuwae N, Regidor DL, Kovesdy CP, Kilpatrick RD, Shinaberger CS, McAllister CJ, Budoff MJ, Salusky IB, Kopple JD: Survival predictability of time-varying indicators of bone disease in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 70: 771–780, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wald R, Sarnak MJ, Tighiouart H, Cheung AK, Levey AS, Eknoyan G, Miskulin DC: Disordered mineral metabolism in hemodialysis patients: An analysis of cumulative effects in the Hemodialysis (HEMO) Study. Am J Kidney Dis 52: 531–540, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Slatopolsky E, Weerts C, Lopez-Hilker S, Norwood K, Zink M, Windus D, Delmez J: Calcium carbonate as a phosphate binder in patients with chronic renal failure undergoing dialysis. N Engl J Med 315: 157–161, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malberti F, Surian M, Colussi G, Poggio F, Minoia C, Salvadeo A: Calcium carbonate: A suitable alternative to aluminum hydroxide as phosphate binder. Kidney Int Suppl 24: S184–S185, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malberti F, Surian M, Poggio F, Minoia C, Salvadeo A: Efficacy and safety of long-term treatment with calcium carbonate as a phosphate binder. Am J Kidney Dis 12: 487–491, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chertow GM, Burke SK, Raggi P; Treat to Goal Working Group : Sevelamer attenuates the progression of coronary and aortic calcification in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 62: 245–252, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suki WN, Zabaneh R, Cangiano JL, Reed J, Fischer D, Garrett L, Ling BN, Chasan-Taber S, Dillon MA, Blair AT, Burke SK: Effects of sevelamer and calcium-based phosphate binders on mortality in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 72: 1130–1137, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Finn WF; SPD 405-307 Lanthanum Study Group : Lanthanum carbonate versus standard therapy for the treatment of hyperphosphatemia: Safety and efficacy in chronic maintenance hemodialysis patients. Clin Nephrol 65: 191–202, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Finn WF, Joy MS, Hladik G; Lanthanum Study Group : Efficacy and safety of lanthanum carbonate for reduction of serum phosphorus in patients with chronic renal failure receiving hemodialysis. Clin Nephrol 62: 193–201, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palmer SC, Gardner S, Tonelli M, Mavridis D, Johnson DW, Craig JC, French R, Ruospo M, Strippoli GF: Phosphate-binding agents in adults with CKD: A network meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am J Kidney Dis 68: 691–702, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sekercioglu N, Thabane L, Díaz Martínez JP, Nesrallah G, Longo CJ, Busse JW, Akhtar-Danesh N, Agarwal A, Al-Khalifah R, Iorio A, Guyatt GH: Comparative effectiveness of phosphate binders in patients with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. PLoS One 11: e0156891, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patel L, Bernard LM, Elder GJ: Sevelamer versus calcium-based binders for treatment of hyperphosphatemia in CKD: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 232–244, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.