Abstract

Objective

Depressive symptoms and drinking to cope with negative affect increase the likelihood for drinking-related negative consequences among college students. However, less is known about their influence on the naturalistic trajectories of alcohol-related consequences. In the current study, we examined how positive and negative drinking-related consequences changed as a function of depressive symptoms and drinking motives (coping, conformity, social, enhancement).

Method

Participants (N = 652; 58% female) were college student drinkers assessed biweekly during the first two years of college. We used hierarchical linear modeling to examine means of and linear change in positive and negative consequences related to depression and motives, controlling for level of drinking.

Results

Consistent with hypotheses, negative and positive consequences decreased over the course of freshman and sophomore years. Higher levels of depression were associated with a faster decline in negative consequences during freshman year. Coping motives predicted average levels of negative and positive consequences across all years, with the effects of coping motives on consequences most pronounced at low levels of depression during sophomore year.

Conclusions

These findings indicate that screening students for depression and drinking to cope, independent of alcohol consumption, may help identify students at risk for experiencing negative alcohol consequences and that these factors should be addressed in targeted alcohol interventions.

Keywords: Depressive symptoms, Alcohol consequences, College students, Coping motives, Longitudinal

1. Introduction

Approximately one-third of college students are at least mildly depressed (Gress-Smith, Roubinov, Andreotti, Compas, & Luecken, 2013; for review see Ibrahim, Kelly, Adams, & Glazebrook, 2013), and data from college counseling centers show a rise in chronic and severe depression (Barr, Rando, Krylowicz, & Winfield, 2010; Gallagher, 2012). Factors contributing to increasing mental health issues on college campuses may include advances in treatment and the widespread use of psychotropic medication that enable students with preexisting mental health disorders to attend college, heightened academic pressures, and a lack of adaptive skills needed to adequately cope with new environments (Compton, Conway, Stinson, & Grant, 2006). Students with depressive symptoms experience substantially higher rates of drinking-related negative consequences, including alcohol use disorders, relative to non-depressed peers (Martens, Martin, et al., 2008; Miller, Miller, Verhegge, Linville, & Pumariega, 2002). However, no studies to date have prospectively examined how depressive symptoms impact trajectories of drinking-related consequences during college. Gaining a perspective on the natural history of alcohol-related consequences and exploring how these outcomes differ by known factors of alcohol risk (e.g., depression) will inform targeted intervention and health promotion efforts.

1.1 Depressive Symptoms and Drinking to Cope

The motivational model of alcohol use (Cox & Klinger, 1988, 1990) posits that motivation for drinking is a necessary prerequisite and the most proximal predictor of alcohol consumption. In accordance with theory, one's decision to drink rests in the expected affective outcomes of drinking. From a clinical perspective, understanding how motives contribute to drinking behaviors during potentially risky transitions to college can inform avenues for modifying students' motives for high-risk drinking. Of all motives (social, enhancement, coping, conformity), drinking to cope with negative affect is the strongest predictor of drinking-related negative consequences among college students (Kuntsche, Knibbe, Gmel, & Engels, 2005; Kuntsche, Stewart, & Cooper, 2008), and students reporting higher coping motives are found to experience higher levels of negative consequences (e.g., impaired control, academic/occupational problems, physiological dependence) one year later (Merrill et al., 2014).

Consuming alcohol to cope with distress or to escape problems appears to play a fundamental role in the drinking decisions of students with depressive symptoms (Holt et al., 2013; Martens, Neighbors, et al., 2008). Kenney and colleagues (2015) found that endorsement of drinking to cope with negative affect (both in the year prior to and during the first year of college) was a primary mechanism through which depressed mood at college entry predicted women's experience of negative alcohol consequences during college. However, results from fixed-interval (e.g., daily diary) and time-to-drink (e.g., drinking sooner in the week) approaches examining the moderating role of global drinking to cope motives in the relationship between negative affect and drinking have been inconsistent. While some studies demonstrate that students with higher drinking to cope motives drank earlier in weeks (Armeli, Todd, Conner, & Tennen, 2008) and more on days (Mohr et al., 2005) associated with negative moods, other studies fail to find moderating effects (Armeli, Conner, Cullum, & Tennen, 2010; Littlefield, Talley, & Jackson, 2012; O'Hara, Armeli, & Tennen, 2014). Still, it is not known how depression and coping motives influence prospective trends in consequences during college or how depressive status and coping motives may interact to predict trends in consequences. Identifying how depressive status and drinking to cope are associated with trajectories of risk during this critical developmental period will more broadly explicate trends in risk and provide valuable implications for targeted intervention.

1.2 Trends in Negative and Positive Consequences

Overall, students experience a peak in alcohol-related negative consequences in the first year of college (O'Neill, Parra, & Sher, 2001), after which negative consequences decline (Hustad, Carey, Carey, & Maisto, 2009; Schulenberg et al., 2001). Declining trends may be due to an initial ceiling effect in which students tend to experience the most extreme risk during the transition to college, which naturally declines thereafter. Still, although students appear to learn to drink more safely over time, reductions are not sharp and associated risks continue to remain extreme relative to the general population. Further, although negative consequences exhibit general declines overall, this is not the case for all students; therefore, identifying risk factors associated with less decline is needed to benefit students facing heightened risk.

Positive alcohol-related consequences (e.g., feeling more self-confident and sure of self, easier to socialize) receive less attention in research than negative consequences even though positive consequences are more strongly endorsed (Corbin, Morean, & Benedict, 2008; Park, Armeli, & Tennen, 2004) and are as strongly predictive of students' future drinking behaviors and intentions to drink (Lee, Maggs, Neighbors, & Patrick, 2011; Park et al., 2004; Usala, Celio, Lisman, Day, & Spear, 2015). Because the motivational model of alcohol use focuses on drinkers' desire to achieve positive outcomes, assessing how motives for drinking predict positive drinking-related consequences will provide a more comprehensive understanding of students' drinking-related trajectories. To our knowledge, only one study, using data from the current sample, examined trends in both negative and positive consequences. This study revealed declines in both types of consequences over the course of the first year of college, but did not explore moderators of these trends or whether similar declines occurred in sophomore year (Barnett, Clerkin, Wood, Monti, O'Leary Tevyaw, et al., 2014).

Gaining a better understanding of prospective alcohol outcomes is particularly important for at-risk students experiencing depressed mood who may rely on alcohol for its rewarding effects, and therefore may perceive greater benefits from drinking. In fact, negative affect among college students is associated with greater experience of both negative and positive consequences (Park & Grant, 2005; Park & Levenson, 2002), indicating that positive experiences may reinforce risky drinking behaviors despite negative experiences. In Kenney et al's (2015) longitudinal study, women matriculating into college with (versus without) depressed mood exhibited steeper declines in negative alcohol-related consequences during the first year of college despite stable drinking levels and depressive symptoms, and higher overall negative consequences. Building on this prior work, the current study examined how naturalistic rates of change in students' negative and positive consequences differed as a function of depressed mood and drinking motives (known predictors of alcohol risk) over the course of freshman and sophomore years.

1.3 Study Aims and Objectives

Using data from a large multi-site sample of students who completed biweekly assessments during each of the first two years of college, we first tested the hypothesis that the frequency of both positive and negative consequences would decline across each of the first two years. Second, we tested the hypothesis that students reporting stronger levels of drinking to cope with negative affect would exhibit lower rates of change in consequences relative to peers (i.e., their frequency of negative and positive consequences would remain more constant and/or decline less rapidly). Given inconsistencies between recent empirical findings (showing faster declines in the frequency of negative consequences among depressed students) and cross-sectional literature that finds substantially greater alcohol risk among depressed students, we examined trends by depressive status without a hypothesis. Third, we predicted that participants reporting higher (versus lower) levels of depressed mood and higher (versus lower) coping motives would experience more positive and negative consequences, on average, across the course of two years. Finally, we tested the hypothesis that coping motives would moderate the relationship between depressed mood and consequences, such that higher endorsement of drinking to cope should be particularly risk enhancing (i.e., result in higher average frequency of negative consequences across the two years) for depressed participants.

2. Method

2.1 Participants

Participants were 652 incoming college students in a two-year longitudinal study assessing naturalistic changes in drinking-related beliefs and behaviors. The present study sample had a mean age of 18.37 years (SD=0.45) at baseline and was 58% female. Racial composition was: 67% White, 9% Asian, 6% African American, 0.3% Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, 0.2% Native Hawaiian or Alaska Native, 11% Multiracial, and 7% unknown/other. Additionally, 7% reported Hispanic ethnicity.

In the larger study from which these data were drawn, 1,053 participants were enrolled across three consecutive years (2004-2006) from three universities/colleges in New England (U.S.). Because we were interested in trends in consequences, participants were excluded if they did not report any drinking (n = 241; 22.9%) over the course of the study or at baseline (n=139, because motives were only assessed among baseline drinkers), leaving a sample of 673 drinkers. We then retained all possible participants who could contribute data during either or both their freshman and sophomore year. In the freshman year data, another 21 participants were deleted for missing data on biweekly level. The final sample for the freshman data was N = 652. In sophomore year, 87 of the 673 drinkers were deleted listwise due to missing data on between-person variables of interest and 61 were deleted for missing data on biweekly level consequences, leaving a final sophomore sample of N = 525.

2.2 Design and Procedure

A gender-stratified random sample of incoming students that oversampled students who were not exclusively non-Hispanic White was invited to participate. Inclusion criteria were < 21 years old; full-time, non-international student status; and living on campus. In the summer before arriving on campus selected students were mailed a study description, informed consent form, information about how to enroll online using a unique username and password, and $5 for considering participation. For students under 18 years parental consent was obtained. In all, 1,053 (37%) of invited students enrolled in the study.

2.2.1 Data collection

After consent and prior to arriving on campus, participants completed the online baseline survey (Time 1). After the end of the first week on campus participants began receiving biweekly online surveys. Participants were invited to complete a total of 18 biweekly surveys during each academic year. At the end of the first year of college (mid-May), participants completed a second annual (Time 2) online survey. Completers received $20 and $25 for the two annual surveys, $2 and raffle entries for each biweekly survey, and bonuses for high response rates. The Institutional Review Boards of the participating universities approved all procedures.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Annual Survey Measures

Demographics were measured only at Time 1.

Depression

The 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) measured past week depressive symptoms using a four-point scale: 0 (Rarely or none of the time [less than 1 day]) to 3 (Most or all of the time [5-7 days]). Depressed mood reported at Time 1 and Time 2 was used in freshman and sophomore year analyses, respectively.

Drinking motives

were assessed at the Time 1 and Time 2 annual surveys using the four-item subscale of the 20-item Drinking Motives Questionnaire (DMQ; Cooper, 1994). Respondents were asked reasons for drinking in the past 30 days. Response options are 1 (almost never/never) to 5 (almost always/always), with five items summed to create each of the following four subscales: social (α= .87 (T1) and .89 (T2)), enhancement (α = .89 and .86, coping (α = .81 and .84), and conformity (α = .84 and .81).

2.3.2 Biweekly Survey Measures

Drinks per week

Using an automatically produced past-week diary grid, participants reported the number of standard drinks consumed on each day. Total drinks were summed for a weekly drinks variable.

Negative and positive consequences

For each biweekly survey on which participants reported any drinking, they were asked whether in the past week they had any of 11 positive (e.g., “It was easier to socialize,” “I felt less stressed and more relaxed,” “I felt more self-confident and sure of myself.”) and 13 negative (e.g., “I disappointed others that are close to me,” “I passed out,” “I had a romantic or sexual activity that I now regret.”) consequences selected to best capture different consequence domains (e.g., external versus internal) and severity from well-established measures of positive and negative alcohol outcomes (e.g., Kahler, Strong, & Read, 2005; Noar, Laforge, Maddock, & Wood, 2003). Numbers of endorsed positive and negative consequences were separately summed for each week.

2.4 Data Analytic Plan

During the data preparation stage, we averaged across biweekly assessments to create quarterly measures of drinking and consequences. We chose this approach because the drinking behavior and number of consequences experienced was highly variable week-to-week (e.g., heavy drinking, high consequence weeks followed by low- or non-drinking weeks, making linear trajectories of weekly consequences less appropriate). Quarterly aggregates provide more reliable characterizations of drinking behavior across a series of weeks, normally distributed outcome measures, and observation of linear trends in the data.

To account for the non-independence of the repeated quarterly measures, hierarchical linear models (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) were run in HLM 7.01 (Raudenbush, Bryk, & Congdon, 2013). We ran models separately on data collected during freshman and sophomore years for several reasons. First, the between-person predictors of interest (depression, motives) were assessed prior to each respective academic year (T1, T2), so separate models allowed us to use the between-person predictors measured as close in time as possible to the estimated trajectories of consequences. Second, we conducted a preliminary analysis of data collected across both years, and found significant interactions between assessment number (with each biweekly assessment given a dummy code) and class year on both negative and positive consequences, suggesting that the rate at which consequences change over time differs between year, such that they declined faster in freshmen than in sophomore year (negative consequences, class year × time interaction: B=.05, SE=.23, p=.05; positive consequences: B=.67, SE=.18, p<.01)1.

At the within-persons level (Level 1), the slope of time (coded from 0 [quarter 1] to 3 [quarter 4]) allowed for estimation of linear change in consequences over the course of the year. At Level 1, we controlled for quarterly aggregates of drinks per week, to test whether depression and motives were associated with consequences above and beyond level of drinking. At the between-persons level (Level 2), predictors of both the intercept (mean) and slope of consequences over time included depression and drinking motives. Inclusion of all four drinking motives in a single model allowed us to control for shared variance among motives (i.e., a general motivation to drink) and examine the unique influence of each motive. We also modeled aggregate effects of drinks per week (average across all assessments) on the intercept of consequences to control for the potential between-person influence of greater alcohol involvement on consequences. Because a test of whether gender was associated with our outcome variables was non-significant, consistent with research indicating that while males may drink more than females they do not necessarily experience more consequences (Barnett, Clerkin, Wood, Monti, O'Leary Tevyaw, et al., 2014; Perkins, 2002; Sugarman, DeMartini, & Carey, 2009), we chose not to include gender in further analyses.

Negative consequences was square-root transformed to address non-normality; positive consequences was normally distributed. Level 2 predictors were grand-mean centered to facilitate interpretation of the estimates and reduce multicollinearity. The effect of time at L1 also was centered in order to examine effects of predictors of interest on average levels of consequences across all quarters. Intercept and slope effects were treated as random to account for potential differences between participants in both average levels and change over time in consequences; however, non-significant random slopes were fixed in final models. First, fully unconditional models predicting consequences were estimated and the intraclass correlations (ICC) computed. Then, Level 1 and Level 2 predictors were added to test hypotheses.

3. Results

3.1 Descriptives

The ICC of negative consequences was .41 and .44 in freshman and sophomore year, respectively, indicating that 41-44% of the variance in consequences was between-individuals. The ICC of positive consequences was .53 and .64 in freshman and sophomore year, respectively. In the freshman year biweekly data, there were 2,608 possible quarterly data points (N = 652 × 4 quarters), and 2,160 (83%) were complete (i.e., the participant completed at least one survey within that quarter, allowing us to calculate a quarterly average). In the sophomore year data, there were 2,100 possible data points (N = 525 × 4 quarters), and 1,797 (86%) were complete.

In freshmen year 19.3% and in sophomore year 22.5% of the sample met criteria (i.e., score of 16+) for clinically significant levels of psychological stress (Radloff, 1977). Depressive symptoms were correlated with negative consequences and coping motives in both years, and positive consequences in freshman year only (Table 1). Positive and negative consequences were significantly intercorrelated and associated with greater levels of drinking and endorsement of coping motives in both years.

Table 1. Correlation Matrix and Descriptive Statistics of Study Variables.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | Freshman M (SD) | Sophomore M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Depressive symptoms | — | -.14** | .01 | .11* | .31*** | .18*** | -.04 | -.06 | .12** | 10.68 (8.41) | 11.51 (8.91) |

| 2 | Quarterly drinks/week | -.04 | — | .16*** | .34*** | .07 | -.03 | .22*** | .33*** | -.25*** | 6.86 (6.85) | 6.98 (6.75) |

| 3 | Positive consequences | .10* | .23*** | — | .38*** | .29*** | .25*** | .38*** | .33*** | .04 | 4.20 (2.23) | 3.41 (2.21) |

| 4 | Negative consequences | .24*** | .43*** | .49*** | — | .26*** | .07 | .22*** | .22*** | .05 | 0.90 (0.99) | 0.66 (0.78) |

| 5 | Coping motives | .39*** | .24*** | .29*** | .34*** | — | .40*** | .44*** | .34*** | .13** | 1.59 (0.69) | 1.73 (0.76) |

| 6 | Conformity motives | .15*** | -.02 | .19*** | .14*** | .31*** | — | .40*** | .23*** | -.02 | 1.39 (0.61) | 1.50 (0.64) |

| 7 | Social motives | .06 | .31*** | .36*** | .25*** | .47*** | .35*** | — | .66*** | .01 | 2.87 (1.05) | 3.15 (1.02) |

| 8 | Enhancement motives | .01 | .38*** | .34*** | .31*** | .42*** | .19*** | .70*** | — | -.04 | 2.66 (1.12) | 2.82 (1.02) |

| 9 | Gender (1 = female) | .07 | -.24*** | .03 | .05 | .03 | -0.09* | -.05 | -.03 | — | — | — |

Note. N = 652 in freshman year (below diagonal); N = 525 in sophomore year (above diagonal). Negative and positive consequences represent average weekly consequences reported at each biweekly survey within each quarter; Quarterly drinks/week represent the average drinks/week reported at each biweekly survey within each quarter; Descriptives for the other variables come from Level 2 (baseline within each year) data.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

3.2 Natural Trends in Consequences

Tables 2 and 3 depict models predicting negative and positive consequences, respectively, for freshman and sophomore years. Consistent with hypotheses, negative and positive consequences significantly decreased over the course of each year (slope). In freshman year only, higher levels of depression were associated with a faster decline in negative consequences over time. The rate of change in negative and positive consequences was not influenced by drinking motives in either year.

Table 2. Hierarchical Linear Models Predicting Negative Consequences.

| Freshman Year | Sophomore Year | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| B (SE) | t | p | B (SE) | t | p | |

| Intercept of Negative Cons | 0.491 (.030) | 16.009 | <0.001 | 0.392 (.027) | 14.291 | <0.001 |

| L2 Predictors of Intercept | ||||||

| Average drinks per week | 0.030 (.004) | 7.558 | <0.001 | 0.024 (.003) | 7.009 | <0.001 |

| Depression | 0.012 (.002) | 5.291 | <0.001 | 0.007 (.002) | 3.923 | <0.001 |

| Coping Motives | 0.068 (.033) | 2.075 | 0.038 | 0.141 (.029) | 4.817 | <0.001 |

| Conformity Motives | 0.074 (.032) | 2.282 | 0.023 | -0.037 (.032) | -1.156 | 0.248 |

| Social Motives | -0.027 (.021) | -1.267 | 0.206 | 0.039 (.025) | 1.516 | 0.130 |

| Enhancement Motives | 0.087 (.019) | 4.585 | <0.001 | 0.027 (.023) | 1.212 | 0.226 |

| Depression × Coping Motives | -0.003 (.002) | -1.269 | 0.205 | -0.005 (.002) | -2.011 | 0.045 |

| Quarterly Drinks (L1 effect) | 0.039 (.003) | 11.400 | <0.001 | 0.025 (.003) | 7.143 | <0.001 |

| Slope of Neg Cons over Time (L1) | -0.050 (.009) | -5.363 | <0.001 | -0.026 (.009) | -2.776 | 0.006 |

| L2 Predictors of Slope of Neg Cons over Time | ||||||

| Depression | -0.004 (.001) | -3.082 | 0.002 | -0.000 (.001) | -0.110 | 0.912 |

| Coping Motives | -0.015 (.017) | -0.920 | 0.358 | -0.016 (.016) | -0.996 | 0.319 |

| Conformity Motives | -0.016 (.017) | -0.957 | 0.339 | -0.017 (.018) | -0.918 | 0.359 |

| Social Motives | -0.007 (.012) | -0.533 | 0.594 | -0.011 (.013) | -0.799 | 0.425 |

| Enhancement Motives | -0.013 (.011) | -1.176 | 0.240 | 0.002 (.012) | 0.165 | 0.869 |

Note. Neg Cons = negative consequences, L1 = Level 1, L2=Level 2

Table 3. Hierarchical Linear Models Predicting Positive Consequences.

| Freshman Year | Sophomore Year | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| B (SE) | t | p | B (SE) | t | p | |

| Intercept | 3.773 (.139) | 27.115 | <0.001 | 3.270 (.130) | 25.099 | <0.001 |

| L2 Predictors of Intercept | ||||||

| Average drinks per week | 0.062 (.018) | 3.504 | <0.001 | 0.028 (.014) | 2.008 | 0.045 |

| Depression | 0.016 (.011) | 1.488 | 0.137 | 0.001 (.010) | 0.147 | 0.883 |

| Coping Motives | 0.326 (.161) | 2.030 | 0.043 | 0.536 (.150) | 3.577 | <0.001 |

| Conformity Motives | 0.353 (.159) | 2.215 | 0.027 | 0.360 (.159) | 2.261 | 0.024 |

| Social Motives | 0.325 (.103) | 3.165 | 0.002 | 0.419 (.117) | 3.596 | <0.001 |

| Enhancement Motives | 0.181 (.096) | 1.881 | 0.060 | 0.222 (.116) | 1.905 | 0.057 |

| Depression × Coping Motives | -0.015 (.011) | -1.491 | 0.136 | -0.038 (.012) | -3.220 | 0.001 |

| Quarterly Drinks (L1) | 0.130 (.012) | 10.766 | <0.001 | 0.108 (.011) | 10.025 | <0.001 |

| Slope of Pos Cons over Time (L1) | -0.433 (.035) | -12.257 | <0.001 | -0.211 (.032) | -6.494 | <0.001 |

| L2 Predictors of Slope of Pos Cons over Time | ||||||

| Depression | -0.005 (.005) | -1.009 | 0.313 | 0.003 (.004) | 0.669 | 0.504 |

| Coping Motives | -0.067 (.070) | -0.965 | 0.335 | 0.023 (.055) | 0.410 | 0.682 |

| Conformity Motives | -0.001 (.064) | -0.022 | 0.982 | 0.010 (.062) | 0.158 | 0.874 |

| Social Motives | 0.010 (.047) | 0.207 | 0.836 | -0.087 (.052) | -1.694 | 0.090 |

| Enhancement Motives | -0.078 (.041) | -1.916 | 0.056 | 0.080 (.050) | 1.610 | 0.108 |

Note. Pos Cons = positive consequences, L1 = Level 1, L2=Level

3.3 Average Levels of Consequences

3.3.1 Negative Consequences

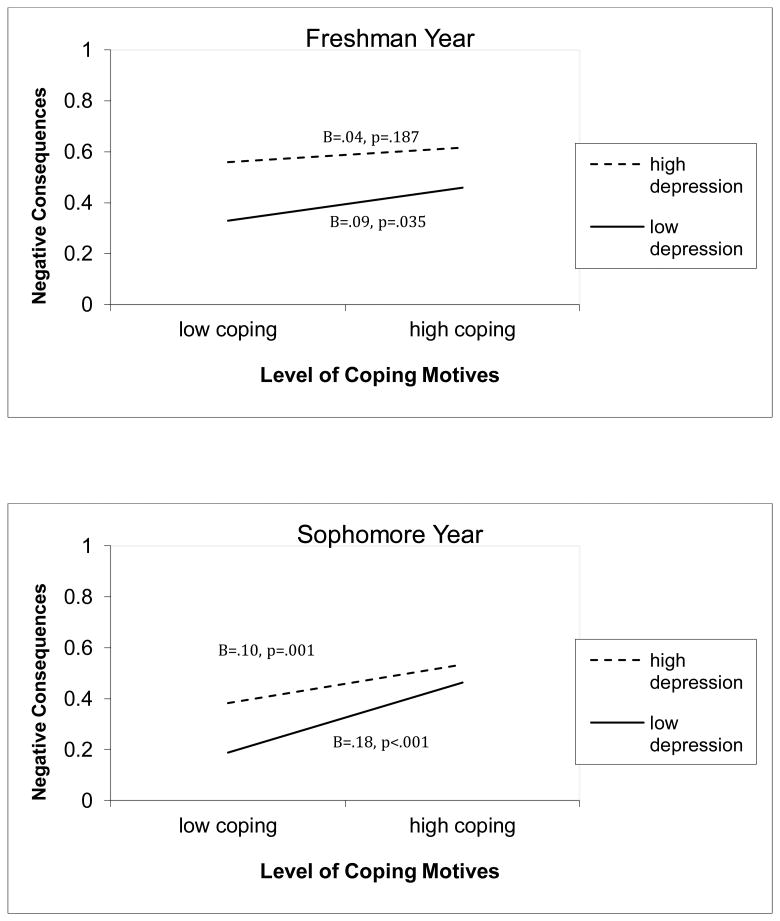

As expected, a higher average number of negative consequences (intercept) was associated with depression and coping motives during both years. During sophomore year, these effects were qualified by a significant interaction between depression and coping motives. We probed this interaction at high and low levels of depression (1 SD above and below the mean, Aiken and West,1991)2, and all simple slopes were significant: the magnitude of the coping motives effect was stronger at low (B=.18, SE=.04, t=4.50, p<.001) than high levels of depression (B=.10, SE=.03, t=3.27, p=.001). In other words, in sophomore year, coping motives were more closely linked to negative consequences among those with fewer symptoms of depression than among those with more symptoms (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Simple slopes of the effect of coping motives on negative consequences at high and low levels of depression in freshman and sophomore year. Note: ns=non-significant

3.3.2 Positive Consequences

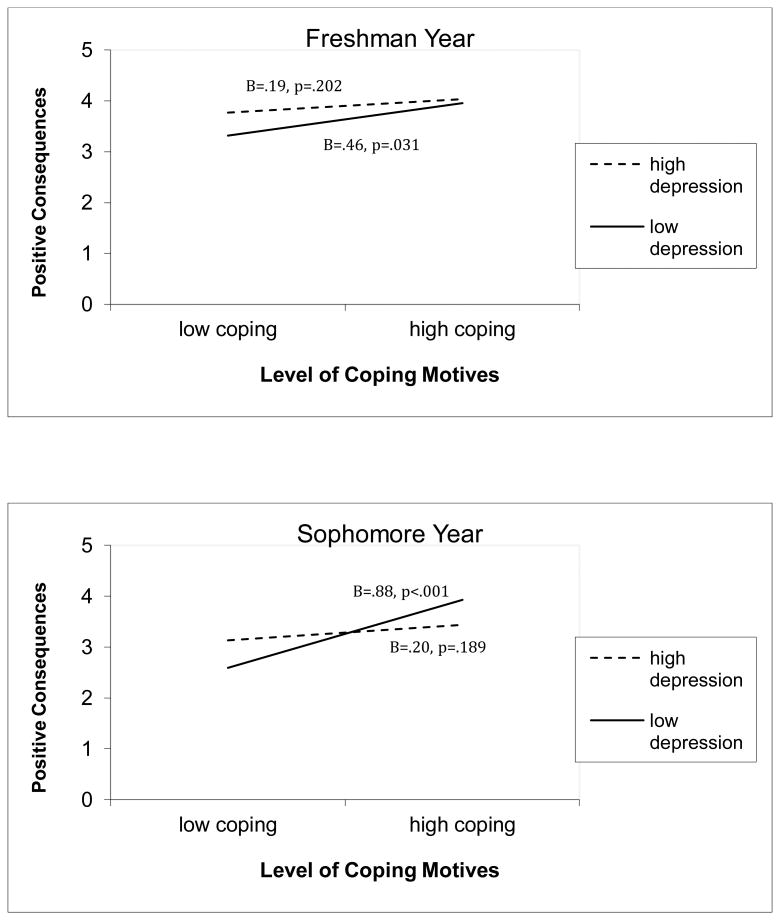

In partial support of hypotheses, more positive consequences (intercept) was associated with coping motives, but not depression, during both years. We also observed an interaction between depression and coping motives on positive consequences in sophomore year, such that higher coping motives were significantly associated with higher levels of positive consequences only at low (B=.88, SE=.20, t=4.45, p<.001) but not high (B=.20, SE=.15, t=1.32, p=.19) levels of depression. That is, in sophomore year, reporting stronger coping motives was linked to more positive consequences only among those with low depression (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Simple slopes of the effect of coping motives on positive consequences at high and low levels of depression in freshman and sophomore year. Note: ns=non-significant

4. Discussion

The current study provides insight into how depressive symptoms and drinking motives influence naturalistic trajectories of positive and negative alcohol-related consequences over the first two years of college. In support of prior research indicating that alcohol-related risk may be greatest early in the first year of college (O'Neill et al., 2001) and decline thereafter (Hustad et al., 2009), we found that negative and positive consequences significantly decreased over the course of freshman and sophomore years in this sample, even after controlling for alcohol consumption. Moreover, findings showed that depressive symptoms and coping motives independently predicted higher overall levels of alcohol-related negative consequences during college. These results confirm and extend the well-documented links found in prior studies (e.g., Kenney et al., 2015; Kuntsche et al., 2005) by using two years of multi-site data that controlled for prior and current drinking levels as well as other motives for drinking.

The escalated risk among depressed students appears to be pronounced early in college, a concerning finding given the importance of college transitions to the healthy adaptation to college life (NIAAA, 2002). However, despite depressed students' greater overall risk, we found that higher levels of depressive symptoms were associated with a steeper decline in negative consequences during freshman year. These results are consistent with Kenney et al.'s recent findings (2016) examining first-year college women. It is plausible that students matriculating into college with depressive symptoms are particularly sensitive to their experience of negative consequences and hence reduce risk behaviors. Based on operant learning theory (Skinner, 1953), consequences perceived to be highly aversive may motivate depressed students to modify behaviors (i.e., via avoidance learning) in order to reduce the likelihood that a consequence will reoccur. Further, gaining a better understanding of how subjective evaluations of alcohol-related consequences may differ by depressive status is an area for future research, since it is possible that depressed students perceive negative and positive consequences differently from non-depressed students. It is also possible that students experiencing significantly more consequences than peers may modify their behaviors or underestimate their responses in order to adhere to peer norms. Regardless, future research is needed to determine if similar declining trajectories emerge in other large representative samples and identify risk reduction mechanisms that may play a role in depressed students drinking-related experiences.

During sophomore year, while both depressive symptoms and coping motives were linked to escalated negative alcohol consequences, coping motivated drinking was particularly risk-enhancing among those with fewer depressive symptoms. Even though lower levels of depressed mood are associated with a lower likelihood to drink to cope, less depressed students may drink to cope because of a singular, volatile issue (e.g., relationship problem) that increases event-level risk. Although it is beyond the scope of this study to examine these mechanisms, identifying the events or situations that trigger drinking to cope, assessing for maladaptive problem-solving or conflict resolution skills, and extrapolating patterns of drinking to cope behaviors and consequences may clarify the coping skills and drinking alternatives most beneficial to students.

The present findings demonstrate that positive consequences may play a particularly important role in the trajectories of students reporting greater drinking to cope. Despite escalated negative consequences, drinking to cope predicted more positive consequences, indicating that positive outcomes may reinforce coping incentivized drinking (e.g., having a good time and increased sociability, tension reduction) and lead to increasing reliance on drinking as a coping mechanism (Littlefield, Sher, & Wood, 2010). These findings are consistent with theories of negative urgency (e.g., drinking excessively in response to extreme negative affect) that focus on the intensity and state of negative emotions that predispose individuals to drink excessively to achieve immediate desired objectives (Cyders & Smith, 2008). As such, drinkers incentivized to drink in response to adverse feelings (e.g., nervousness, lack of confidence) may experience positive consequences (e.g., easier to socialize), regardless of depressive or anxious state and despite increased risk for negative consequences. Routine assessment of positive consequences and qualitative research that illuminates how inter- and intra-personal factors relate to students' motives for drinking and both positive and negative experiences are warranted.

The finding that higher coping motives were more strongly associated with positive consequences at low (versus high) levels of depressive symptoms indicates that non-depressed students may garner particular benefit from drinking to cope with temporary aversive states than more depressed peers who may drink to self-medicate or escape problems. Given the strong correlation between depressive symptoms and coping motives, it is likely that coping motives for drinking are more entrenched among more, relative to less, depressed students. Perhaps less depressed students are better able to obtain the positive outcomes of coping motivated drinking (e.g., self-confidence) that are more challenging for depressed students to access. Indeed, students who drink to avoid problems that are never adequately resolved are at greater risk for enduring maladaptive drinking behaviors than peers who drink to cope with acute issues (e.g., bad grade) (Kassel, Jackson, & Unrod, 2000).

4.1 Limitations

Depressive symptoms and drinking motives were assessed on an annual basis, which did not capture variability in predictors that might have occurred during the course of the respective years. Daily diary and ecological momentary assessment (EMA) methods that account for change and proximity to coping motives may be particularly informative given that global measures of drinking to cope fail to capture contextual processes (O'Hara, Armeli, & Tennen, 2014). Second, we did not account for other mental health issues that are uniquely linked with drinking to cope, such as anxiety (Grant, Stewart, & Mohr, 2009; Lewis et al., 2008) or life stressors (Digdon & Landry, 2013; Merrill & Thomas, 2013). Future research should account for a wider spectrum of mental health constructs. Next, because they could not contribute to our aims, we excluded one-third of the original respondent pool, including abstainers, who did not report a drinking-related negative consequence. Therefore, results may overestimate students' experience of consequences and lack generalizability. Finally, the current analyses also did not account for several known predictors of alcohol risk, such as fraternity/sorority membership (Park, Sher, & Krull, 2008) and athlete status (Martens, 2012), and factors known to protect students from experiencing alcohol-related negative consequences, such as religiosity (Menagi, Harrell, & Lee, 2008), familial and peer social support (Dulin, Hill, & Ellingson, 2006), and use of protective behavioral strategies (PBS; Martens et al., 2005; e.g., “avoid drinking games”). It is particularly important for future research to examine the role of PBS in these relationships given that lesser PBS use mediates the relationship between both depressed mood (LaBrie, Kenney, & Lac, 2010; LaBrie, Kenney, Lac, & Garcia, 2009) and drinking to cope motives (Bravo, Prince, & Pearson, 2015; LaBrie et al., 2011) on alcohol risk outcomes among college students.

4.2 Implications

These findings highlight negative affect and drinking to cope as important risk factors in college students' experience of drinking-related consequences, over and above alcohol consumption, and across two years of biweekly assessment. Interventions that screen students for risk based on heavy drinking criteria alone may be inadequate. Rather, identifying and screening students for depressive symptoms or endorsement of drinking to cope, whether linked to depressed mood or not, appear to be important targets for prevention efforts. Targeted interventions that provide coping skills training (e.g., stress management) or leverage students' prior experience, subjective evaluations, and future expectancies of negative and positive alcohol outcomes may be particularly effective.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants K01AA022938 (Merrill), T32AA007459 (Kenney), and R01AA013970 (Barnett) from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Footnotes

We considered running (for each outcome) a piecewise growth model across the two years to uniquely predict each year's slope in a single model; however, this was determined to be a less parsimonious and appropriate approach as (a) a break in biweekly assessments during the summer months would have required inclusion of an additional time covariate, (b) inclusion of all predictors measured twice (T1, T2) in a single model had the potential for problems related to multicollinearity, and (c) while this would allow separate prediction of slopes in each year, we were also interested in predicting the intercept (mean) of consequences separately in each year, which cannot be done in a single model.

Following recommendations of Aiken & West (1991), we probed our simple slopes at 1SD above and below the mean on the CESD at each year. Thus, in freshmen year, where the mean CESD score was 10.68 (SD=8.41), high and low depression represented 19.09 and 2.27, respectively. In our freshmen year sample, 14% of participants actually scored 19 or higher on the CESD and about 12% scored 2 or lower. In sophomore year, where the mean CESD score was 11.51 (SD=8.91), high and low depression represented 20.42 and 2.60, respectively. In our sophomore year sample, 14% of participants actually scored 20 or higher and 14.5% scored 3 or lower. These proportions are similar to those we would observe in a perfectly normal distribution, where 16% of the sample should fall one standard deviation above and 16% of the sample should fall one standard deviation below the mean.

References

- ACHA. American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment II: Reference Group Undergraduates Executive Summary Spring 2013. Hanover, MD: American College Health Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Armeli S, Conner TS, Cullum J, Tennen H. A longitudinal analysis of drinking motives moderating the negative affect-drinking association among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:38–47. doi: 10.1037/a0017530. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0017530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armeli S, Todd M, Conner TS, Tennen H. Drinking to cope with negative moods and the immediacy of drinking within the weekly cycle among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol & Drugs. 2008;69:313–322. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Clerkin EM, Wood M, Monti PM, O'Leary Tevyaw T, Corriveau D, Kahler CW. Description and Predictors of Positive and Negative Alcohol-Related Consequences in the First Year of College. Journal of Studies on Alcohol & Drugs. 2014;75(1):103–114. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr V, Rando R, Krylowicz B, Winfield E. The Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors annual survey: Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Beets MW, et al. Longitudinal patterns of binge drinking among first year college students with a history of tobacco use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;103(1-2):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo AJ, Prince MA, Pearson MR. Does the how mediate the why? A multiple replication examination of drinking motives, alcohol protective behavioral strategies, and alcohol outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2015;76:872–883. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Conway KP, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Changes in the Prevalence of Major Depression and Comorbid Substance Use Disorders in the United States Between 1991-1992 and 2001-2002. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(12):2141–2147. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.12.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6(2):117–128. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin WR, Morean ME, Benedict D. The Positive Drinking Consequences Questionnaire (PDCQ): Validation of a new assessment tool. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33(1):54–68. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox WM, Klinger E. A motivational model of alcohol use. Jounral of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97(2):168–180. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox WM, Klinger E. Incentive motivation, affective change, and alcohol use: A model. In: Cox WM, editor. Why people drink Parameters of alcohol as a reinforcer. New York: Oxford7 Gardner Press; 1990. pp. 291–314. [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: Positive and negative urgency. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:807–828. doi: 10.1037/a0013341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digdon N, Landry K. University students' motives for drinking alcohol are related to evening preference, poor sleep, and ways of coping with stress. Biological Rhythm Research. 2013;44(1):1–11. doi: 10.1080/09291016.2011.632235. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dulin PL, Hill RD, Ellingson K. Relationships among religious factors, social support, and alcohol abuse in a western U.S. college student sample. Journal of Alcohol & Drug Education. 2006;50(1):5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher RP. Thirty Years of the National Survey of Counseling Center Directors: A Personal Account. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy. 2012;26(3):172–184. doi: 10.1080/87568225.2012.685852. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grant VV, Stewart SH, Mohr CD. Coping-anxiety and coping-depression motives predict different daily mood-drinking relationships. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23(2):226–237. doi: 10.1037/a0015006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gress-Smith JL, Roubinov DS, Andreotti C, Compas BE, Luecken LJ. Prevalence, Severity and Risk Factors for Depressive Symptoms and Insomnia in College Undergraduates. Stress And Health: Journal Of The International Society For The Investigation Of Stress. 2013 doi: 10.1002/smi.2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson H, Rundberg J, Zetterlind U, Johnsson KO, Berglund M. Two-year outcome of an intervention program for university students who have parents with alcohol problems: a randomized controlled trial. Alcoholism, Clinical And Experimental Research. 2007;31(11):1927–1933. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton ME. A comparison of a prospective diary and two summary recall techniques for recording alcohol consumption. British Journal of Addiction. 1989;84(9):1085–1092. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb00792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt LJ, Armeli S, Tennen H, Austad CS, Raskin SA, Fallahi CR, Pearlson GD. A person-centered approach to understanding negative reinforcement drinking among first year college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38(12):2937–2944. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hustad JTP, Carey KB, Carey MP, Maisto SA. Self-regulation, alcohol consumption, and consequences in college student heavy drinkers: A simultaneous latent growth analysis. Journal Of Studies On Alcohol And Drugs. 2009;70(3):373–382. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim AK, Kelly SJ, Adams CE, Glazebrook C. A systematic review of studies of depression prevalence in university students. Journal Of Psychiatric Research. 2013;47(3):391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR, Read JP. Toward efficient and comprehensive measurement of the alcohol problems continuum in college students: The brief young adult alcohol consequences questionnaire. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29(7):1180–1189. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171940.95813.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD, Jackson SI, Unrod M. Generalized expectancies for negative mood regulation and problem drinking among college students. Journal Of Studies On Alcohol. 2000;61(2):332–340. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney SR, Abar C, O'Brien K, Clark G, LaBrie JW. Trajectories of alcohol use and consequences in college women with and without depressed mood. Addictive Behaviors. 2016;53:19–22. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney SR, Jones RN, Barnett NP. Gender differences in the effect of depressive symptoms on alcohol expectancies, coping motives, and alcohol outcomes in the first year of college. Journal Of Youth And Adolescence. 2015;44(10):1884–1897. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0311-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney SR, LaBrie JW. Use of protective behavioral strategies and reduced alcohol risk: Examining the moderating effects of mental health, gender and race. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27(4):997–1009. doi: 10.1037/a0033262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25(7):841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Stewart SH, Cooper ML. How stable is the motive-alcohol use link? A cross-national validation of the Drinking Motives Questionnaire Revised among adolescents from Switzerland, Canada, and the United States. Journal Of Studies On Alcohol And Drugs. 2008;69(3):388–396. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Kenney SR, Lac A. The use of protective behavioral strategies is related to reduced risk in heavy drinking college students with poorer mental and physical health. Journal of Drug Education. 2010;40:361–378. doi: 10.2190/DE.40.4.c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Kenney SR, Lac A, Garcia JA, Ferraiolo P. Mental and social health impacts the use of protective behavioral strategies in reducing risky drinking and alcohol consequences. Journal of College Student Development. 2009;50:35–49. doi: 10.1353/csd.0.0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Lac A, Kenney SR, Mirza T. Protective behavioral strategies mediate the effect of drinking motives on alcohol use among heavy drinking college students: Gender and race differences. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:354–361. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Maggs JL, Neighbors C, Patrick ME. Positive and negative alcohol-related consequences: Associations with past drinking. Journal of Adolescence. 2011;34(1):87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Hove MC, Whiteside U, Lee CM, Kirkeby BS, Oster-Aaland L, Larimer ME. Fitting in and feeling fine: conformity and coping motives as mediators of the relationship between social anxiety and problematic drinking. Psychology Of Addictive Behaviors: Journal Of The Society Of Psychologists In Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22(1):58–67. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.22.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Do changes in drinking motives mediate the relation between personality change and “maturing out” of problem drinking? Journal Of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119(1):93–105. doi: 10.1037/a0017512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Talley AE, Jackson KM. Coping motives, negative moods, and time-to-drink: Exploring alternative analytic models of coping motives as a moderator of daily mood-drinking covariation. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:1371–1376. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.05.020. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MR. Alcohol interventions for college student-athletes. In: White HR, Rabiner DL, editors. College drinking and drug use. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2012. pp. 203–220. [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Ferrier AG, Sheehy MJ, Korbett K, Anderson DA, Simmons A. Development of the Protective Behavioral Strategies Survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:698–705. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Martin JL, Hatchett ES, Fowler RM, Fleming KM, Karakashian MA, Cimini MD. Protective behavioral strategies and the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related negative consequences among college students. Journal Of Counseling Psychology. 2008;55(4):535–541. doi: 10.1037/a0013588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Neighbors C, Lewis MA, Lee CM, Oster-Aaland L, Larimer ME. The roles of negative affect and coping motives in the relationship between alcohol use and alcohol-related problems among college students. Journal Of Studies On Alcohol And Drugs. 2008;69(3):412–419. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menagi FS, Harrell ZAT, Lee JN. Religousness and college student alcohol use: Examining the role of social support. Journal of Religion and Health. 2008 Jun;47(2):217–226. doi: 10.1007/s10943-008-9164-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Thomas SE. Interactions between adaptive coping and drinking to cope in predicting naturalistic drinking and drinking following a lab-based psychosocial stressor. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38(3):1672–1678. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Wardell JD, Read JP. Drinking motives in the prospective prediction of unique alcohol-related consequences in college students. Journal Of Studies On Alcohol And Drugs. 2014;75(1):93–102. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BE, Miller MN, Verhegge R, Linville HH, Pumariega AJ. Alcohol misuse among college athletes: Self-medication for psychiatric symptoms? Journal of Drug Education. 2002;32(1):41–52. doi: 10.2190/JDFM-AVAK-G9FV-0MYY. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr CD, Armeli S, Tennen H, Temple M, Clark J, Carney MA. Moving beyond the keg party: A daily process study of college student dirnking motivations. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:392–403. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIAAA. A call to action: Changing the culture of drinking at US colleges. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2002. (Vol. NIH publication no. 02-5010) [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Laforge RG, Maddock JE, Wood MD. Rethinking positive and negative aspects of alcohol use: Suggestions from a comparison of alcohol expectancies and decisional balance. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64(1):60–69. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hara RE, Armeli S, Tennen H. Drinking-to-cope motivation and negative mood-drinking contingencies in a daily diary study of college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75:606–614. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.606. http://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2014.75.606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill SE, Parra GR, Sher KJ. Clinical relevance of heavy drinking during the college years: Cross-sectional and prospective perspectives. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15(4):350–359. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.15.4.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL. Positive and negative consequences of alcohol consumption in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29(2):311–321. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Armeli S, Tennen H. The daily stress and coping process and alcohol use among college students. Journal Of Studies On Alcohol. 2004;65(1):126–135. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Grant C. Determinants of positive and negative consequences of alcohol consumption in college students: Alcohol use, gender, and psychological characteristics. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30(4):755–765. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Levenson MR. Drinking to cope among college students: prevalence, problems and coping processes. Journal Of Studies On Alcohol. 2002;63(4):486–497. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park A, Sher KJ, Krull JL. Risky drinking in college changes as fraternity/- sorority affiliation changes: A person-environment perspective. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:219–229. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW. Surveying the damage: A review of research on consequences of alcohol misuse in college populations. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;(SUPPL14):91–100. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2. Newbury Park , CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Congdon R. HLM 7.01 for Windows. Skokie, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc; 2013. [Computer software] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg J, Maggs JL, Long SW, Sher KJ, Gotham HJ, Baer JS, Zucker RA. The problem of college drinking: insights from a developmental perspective. Alcoholism, Clinical And Experimental Research. 2001;25(3):473–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. Science and human behavior. Simon and Schuster; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Sugarman DE, DeMartini KS, Carey KB. Are women at greater risk? An examination of alcohol-related consequences and gender. The American Journal on Addictions. 2009;18(3):194–197. doi: 10.1080/10550490902786991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usala JM, Celio MA, Lisman SA, Day AM, Spear LP. A field investigation of the effects of drinking consequences on young adults' readiness to change. Addictive Behaviors. 2015;41:162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]