Introduction

Atrial fibrillation, the most commonly encountered arrhythmia in clinical practice, is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. Its incidence and prevalence are increasing, and it represents a growing clinical and economic burden. Recent research has highlighted new approaches to both pharmacological and non-pharmacological management strategies. Clinicians need to have a sound working knowledge of atrial fibrillation and to be up to date with the emerging evidence to guide treatment and improve outcomes in these patients.

Sources and selection criteria

In this article, we highlight the recent advances in atrial fibrillation. We searched PubMed/Medline, Embase, and Cochrane databases by using the keywords “atrial fibrillation,” “rate,” “rhythm,” “anticoagulation,” and “non-pharmacological.” We also searched references of recent major articles and key reviews, and we obtained articles where necessary.

Epidemiology

Atrial fibrillation affects an estimated 2.2 million adults in the United States.1 In the United Kingdom alone, more than 46 000 new cases of atrial fibrillation are diagnosed every year.2 The prevalence of atrial fibrillation doubles with each advancing decade from the age of 50.3 Independent risk factors include male sex, increasing age, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, valvular heart disease, and myocardial infarction.4 Left atrial dilatation, left ventricular hypertrophy, and impaired left ventricular systolic function are also associated with atrial fibrillation.5 Compared with people in sinus rhythm, those in atrial fibrillation have a sixfold increased risk of stroke and twofold increased risk of death. For those with rheumatic heart disease, the risk of stroke is increased up to 18-fold.6

Classification

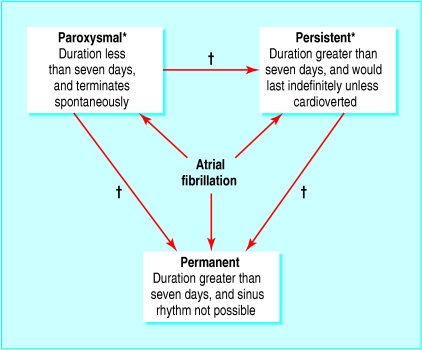

The nomenclature used to classify atrial fibrillation has been diverse. Recent guidelines recommend a classification system based on the temporal pattern of the arrhythmia (fig 1).7

Fig 1.

Classification of atrial fibrillation. *When a patient has had two or more episodes of atrial fibrillation, this is termed recurrent. Both paroxysmal and persistent atrial fibrillation are potentially recurrent arrhythmias. †With time, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation may become persistent; likewise, both paroxysmal and persistent atrial fibrillation may become permanent

Summary points

Although “rhythm control” had been considered superior to “rate control” in managing atrial fibrillation, recent randomised studies have shown neither strategy to be superior

Newer antiarrhythmic agents have been developed, and others are being evaluated for their potential use in atrial fibrillation

Anticoagulation is crucial for prevention of thromboembolic complications; the choice of antithrombotic agent depends on the patient's age, comorbidities, and cardiac status

Warfarin is underprescribed, especially in elderly patients; the benefits of anticoagulation may be greater in such patients

Trials have shown that the oral thrombin inhibitor ximelagatran is as effective as warfarin in the reduction of thromboembolic risk; ximelagatran may become an alternative to warfarin

Non-pharmacological approaches to “rate control,” “rhythm control,” and anticoagulation have been developed and may have an increasing role in the future

Pathophysiology

The causes of atrial fibrillation may be broadly grouped into cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular causes (box 1). The term “lone atrial fibrillation” refers to atrial fibrillation in young people (aged under 60) in whom no apparent cause can be identified.6

Studies have shown that atrial fibrillation results from multiple re-entrant electrical wavelets that move randomly around the atria. These wavelets are initiated by electrical triggers, commonly located in the myocardial sleeves extending from the left atrium to the proximal 5-6 cm portions of the pulmonary veins.8 Other sites in the left and right atria and in the proximal superior vena cava may less frequently trigger atrial fibrillation.9,10 Once triggered, the atrial tissue harbours these wavelets and promotes re-entry, thus facilitating persistence of the arrhythmia. This forms the basis of “atrial remodelling”—a period of atrial fibrillation initially induces electrophysiological changes (“electrical remodelling”) followed by structural changes (“structural remodelling”), which facilitate its persistence.11,12

If atrial fibrillation is associated with poor ventricular rate control, electrical and structural remodelling lead to ventricular dilatation and impairment of systolic function, commonly referred to as “tachycardia induced cardiomyopathy” or “tachycardiomyopathy.”12 Stroke and thromboembolism are a major cause of mortality and morbidity associated with atrial fibrillation, and the underlying pathophysiological basis of this is a prothrombotic or hypercoagulable state, in association with abnormalities of blood flow (atrial stasis, for example) and endothelial or endocardial damage.13

Cardioversion to sinus rhythm

As a result of atrial remodelling, the longer the duration of atrial fibrillation the less successful is the cardioversion. Predictors of recurrence of atrial fibrillation include long standing atrial fibrillation (duration greater than three months), heart failure, structural heart disease, hypertension, increasing age (over 70), and increased left atrial size.14 Although left atrial size is related to the duration of atrial fibrillation, a left atrial diameter greater than 6.5 cm is associated with an increased risk of recurrence.15 Cardioversion carries a 5-7% risk of thromboembolism without anticoagulation and a 1-2% risk after conventional anticoagulation.16 Prolonged anticoagulation is not needed when patients present within 48 hours of onset of atrial fibrillation. Such patients may be safely cardioverted irrespective of whether heparin has been administered since presentation. Administration of heparin is recommended to all patients with an acute presentation, however, to allow flexibility in subsequent management of the arrhythmia.17 For stable patients, in whom the onset of atrial fibrillation is uncertain or greater than 48 hours, anticoagulation for a minimum of three weeks before cardioversion is recommended, to allow resolution of potential thrombi.7 As atrial mechanical activity may not resume concurrently with electrical activity, anticoagulation should be continued for at least four weeks after cardioversion.

An alternative approach is to use transoesophageal echocardiography to exclude atrial thrombi before cardioversion is attempted. The presence of an atrial thrombus necessitates four to six weeks of anticoagulation before cardioversion. Even with this strategy, anticoagulation should be continued for at least four weeks after cardioversion.

Box 1: Causes of atrial fibrillation

Cardiovascular causes

Ischaemic heart disease*

Hypertension*

Mitral valve disease

Mitral stenosis*

Mitral regurgitation

Mitral valve prolapse

Rheumatic heart disease

Heart failure

Cardiomyopathy

Pericarditis

Endocarditis

Myocarditis

Congenital heart disease

Sinus node dysfunction

Cardiac tumours

Post-cardiac surgery

Supraventricular arrhythmia

Wolf-Parkinson-White syndrome

Atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia

Non-cardiovascular causes

Metabolic causes

Thyrotoxicosis*

Low potassium, magnesium, or calcium; acidosis

Phaeochromocytoma

Drugs (sympathomimetics)

Alcohol (“holiday heart syndrome”)

Postoperative (non-cardiac surgery)

Hypothermia

Respiratory causes

Pneumonia

Carcinoma of the lung

Pulmonary embolism

Trauma

Thoracic surgery

Other causes

Vagal atrial fibrillation

Adrenergic atrial fibrillation

Intracranial haemorrhage

“Lone” atrial fibrillation

*Most common causes

Box 2: Guide to rate control

Digoxin is ineffective in controlling ventricular rate during acute episodes and paroxysmal episodes and in states with high sympathetic tone such as thyrotoxicosis, critical illness, and postoperative states. Digoxin is also ineffective for cardioversion

In patients with good left ventricular function, β blockers (metoprolol, propranolol, and atenolol) or non-dihydropyridine calcium antagonists (verapamil and diltiazem) are the drugs of choice, provided no contraindications exist

In patients with acute or chronic heart failure, digoxin or amiodarone should be used. The chronic use of amiodarone is limited by its side effects. β blockers may be considered in patients with stable heart failure

Although digoxin does not provide good rate control in acute episodes, it is generally effective for rate control in persistent atrial fibrillation when used in combination with β blockers and rate limiting calcium antagonists

The adequacy of rate control should be assessed by the clinical symptoms

Target heart rates vary with age. They should generally be 60-90 beats per minutes at rest and 90-115 beats per minute during exercise. This requires careful dose titration

Poor ventricular rate control in the long term leads to a reversible deterioration of left ventricular function (tachycardiomyopathy)

Pharmacological cardioversion

Pharmacological cardioversion is often effective when initiated within seven days of onset of the arrhythmia.18 In general, class I and class III antiarrhythmic agents are commonly used for pharmacological cardioversion and maintenance of sinus rhythm.

In a randomised trial comparing flecainide, propafenone, and amiodarone for cardioversion of recent onset atrial fibrillation, conversion to sinus rhythm occurred in 90%, 72%, and 64% of patients respectively.19 Class IC drugs (flecainide and propafenone) should be avoided in patients with underlying ischaemic heart disease or impaired left ventricular function. Amiodarone can be used in such patients, although the time to conversion can range from days to weeks.20 Dofetilide and ibutilide, newer pure class III agents not currently licensed in the United Kingdom, can also be used for cardioversion.21 With the potential side effects of antiarrhythmic drugs, pharmacological cardioversion should be reserved for haemodynamically stable patients with symptoms.

Electrical cardioversion

Synchronised external direct current cardioversion is a safe procedure with success rates of 70-90%.22 It is used acutely in patients who are haemodynamically compromised or electively as an alternative to pharmacological cardioversion. Electrical cardioversion for atrial fibrillation is usually done under general anaesthesia but has more recently been done under conscious sedation. The current recommendation is to start at 200 J, increasing to 360 J if necessary.7 If this is unsuccessful, adjunctive antiarrhythmic treatment with class III agents such as dofetilide, sotalol, and amiodarone can help to restore sinus rhythm.23,24

Maintenance of sinus rhythm

The relapse rate after cardioversion is high and often necessitates the use of antiarrhythmic treatment. Even then, relapse rates at one year may reach 50%, especially in the presence of comorbidity such as heart failure or uncontrolled hypertension.7

Class IC drugs (flecainide and propafenone) are better tolerated and more effective than class IA drugs (quinidine and disopyramide).25,26 Sotalol is not effective for cardioversion but has some efficacy in maintenance of sinus rhythm.27 Amiodarone may be better than sotalol and class I agents in maintaining sinus rhythm,28 but it is limited by its long term side effects. Dronedarone, a new amiodarone derivative with a better side effect profile, may be a potential alternative to amiodarone.

Ventricular rate control

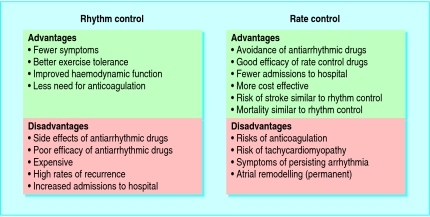

“Rhythm control” and “rate control” are two strategies used in managing atrial fibrillation (boxes 2 and 3). Each strategy has its merits and drawbacks (fig 2). Recent studies have shown that rate control can be considered as a valid alternative to rhythm control (table A on bmj.com). Rhythm control was associated with higher rates of admission to hospital and drug adverse effects, and in one study exercise tolerance was found to be better with rhythm control.w1 In the AFFIRM study of 4060 patients, for example, mortality was higher in the rhythm control arm, although this difference was not statistically significant (22.6% v 17.2%, P = 0.08).w2 However, these “rate versus rhythm” trials have been debated in relation to their applicability to clinical practice, especially as the rate of cross over between study interventions was high, and limited data are available on patients with new onset atrial fibrillation, severe heart failure, or high levels of symptoms, in whom a rhythm control strategy may be unavoidable. None the less, cardioversion should not be done simply as a means of stopping anticoagulation in asymptomatic patients with risk factors for thromboembolism. Indeed, anticoagulation may need to be continued in the long term in patients with such risk factors or those at high risk of recurrence of arrhythmia.

Fig 2.

Advantages and disadvantages of “rate control” and “rhythm control”

Box 3: Guide to rhythm control

Identify and treat all reversible causes of atrial fibrillation before considering drug treatment for maintenance of sinus rhythm

The selection of antiarrhythmic drug needs to be tailored individually to the patient, depending on cardiac status, comorbidities, and contraindications

In patients with good left ventricular function and no coronary artery disease, flecainide and propafenone can be used. Sotalol or amiodarone can also be used in such patients

Amiodarone can be used to maintain sinus rhythm in patients with heart failure. Although not currently licensed in the United Kingdom, dofetilide is an alternative

β blockers are the drugs of choice for patients with coronary artery disease

If sinus rhythm cannot be maintained despite repeated cardioversions and antiarrhythmic treatment, a “rate control” strategy should be adopted. This has been shown to be as effective as rhythm control

Patients who find the symptoms of the arrhythmia unacceptable despite rate control may be considered for non-pharmacological methods to restore sinus rhythm

Reduction of thromboembolic risk

Atrial fibrillation is commonly associated with stroke and thromboembolism. When stroke occurs in association with atrial fibrillation, patients have a greater mortality and morbidity, longer hospital stays, and greater disability than those without atrial fibrillation.

Pooled data from trials comparing antithrombotic treatment with placebo have shown that warfarin reduces the risk of stroke by 62% (95% confidence interval 48% to 72%) and that aspirin alone reduces the risk by 22% (2% to 38%). Overall, in high risk patients, warfarin was better than aspirin in preventing strokes, with a relative risk reduction of 36% (48% to 72%). The risk of major haemorrhage with warfarin was twice that with aspirin.w7

Anticoagulation treatment needs to be tailored individually for patients on the basis of age, comorbidities, and contraindications. We have incorporated risk factors for thromboembolism, derived from major clinical trials,w8-w15 and proposed a simple algorithm for selecting the most appropriate anticoagulant for patients in atrial fibrillation (fig 3). For patients with lone atrial fibrillation and no thromboembolic risk factors, the annual rate of stroke is 1%, and these patients seem to have little to gain from anticoagulation.w8 Such patients may be prescribed aspirin if no contraindications exist.

Fig 3.

Algorithm for anticoagulating patients with atrial fibrillation. *Thyrotoxicosis is associated with a high thromboembolic risk in atrial fibrillation. Current guidelines recommend anticoagulation with warfarin, if no contraindications exist, at least until a euthyroid state is achieved and congestive heart failure has been corrected.7 †Owing to lack of sufficient clear cut evidence, treatment may be decided on an individual basis, and the physician must balance the risks and benefits of warfarin versus aspirin; referral and echocardiography may help in these cases. ‡In patients with older prosthetic valves, the target INR should be higher and aspirin added depending on valve type, valve position, and patient factors. INR=international normalised ratio; CVA=cerebrovascular accident; TIA=transient ischaemic attack

Warfarin remains underprescribed in clinical practice. A review of more than 20 studies of patients with atrial fibrillation showed that only 15-44% of eligible patients were actually prescribed warfarin.w15 Elderly patients are often denied anticoagulation owing to a presumed increased risk of haemorrhagic complications. For such patients, who have a high thromboembolic risk, current data suggest that the benefits of anticoagulation may be greater than in other patients. Indeed, more than 50% of patients with atrial fibrillation in the community are aged over 75,w16 but existing trial data on the effectiveness of warfarin have been derived from selected secondary care populations that under-represent elderly people. The proposed BAFTA trial will assess the risks and benefits of aspirin versus warfarin exclusively in elderly patients with atrial fibrillation in a primary care setting.w17

Warfarin has a narrow therapeutic window and, with its known drug and food interactions, needs regular monitoring. This can be inconvenient for both patients and physicians. Community based studies have shown that patients receiving warfarin have international normalised ratio (INR) values at non-therapeutic levels more than half the time.w18 However, patients who have access to anticoagulation clinics have INR values within the therapeutic range more than 60% of the time.w18 w19 Similarly, monitoring of anticoagulation at clinics has been shown to maintain therapeutic INR values in both elderly patients and younger populations (71.5% and 66.1% respectively, with no statistical difference).w20 Anticoagulation clinics have improved the quality of anticoagulation within the community, and with further research a greater degree of anticoagulation control may be feasible. On the other hand, self monitoring of INR at home may improve the quality and convenience of anticoagulation monitoring. The HOME INR study is comparing this home self monitoring regimen with conventional anticoagulation monitoring at clinics.w21 However, this may be suitable for a only small proportion of patients, considering the age and associated comorbidities of patients with atrial fibrillation.

The limitations of warfarin treatment have prompted the development of new anticoagulants with predictable pharmacokinetics, such that monitoring is unnecessary (table B on bmj.com). Ximelagatran, an oral direct thrombin inhibitor, may be a useful alternative to warfarin. The SPORTIF III and SPORTIF V trials comparing ximelagatran with warfarin found the two agents to be broadly similar.w22 w23 However, approximately 6% of patients on ximelagatran had abnormal liver function tests, so monitoring of liver function will be an important factor.

Idraparinux, a factor Xa inhibitor administered by once weekly subcutaneous injections, is being evaluated in patients with atrial fibrillation in the AMADEUS trial.w24 Oral factor Xa inhibitors are also in development as potential oral anticoagulants.w25 ACTIVE (atrial fibrillation clopidogrel trial with irbesartan for prevention of vascular events) is assessing the role of aspirin plus clopidogrel, compared with adjusted dose warfarin, in the prevention of vascular events in patients with atrial fibrillation.w26

Other new drugs in atrial fibrillation

New antiarrhythmic drugs have been developed and are being evaluated for their potential use in atrial fibrillation (table C on bmj.com). Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blocking drugs have been shown to interfere with atrial remodelling and show great promise in atrial fibrillation.w44

Non-pharmacological therapy

Many non-pharmacological treatments have been developed for the management of atrial fibrillation. Some even afford a possible “cure” (for example, in focal atrial fibrillation), although many have been studied in relatively small numbers of patients who have failed (or cannot tolerate) medical treatment.

Box 4: Outline of the management of atrial fibrillation

Management of the arrhythmia

Rhythm control (restoration and maintenance of sinus rhythm)

Pharmacological: Antiarrhythmic drugs

-

Non-pharmacological: Electrical cardioversion Atrial based pacing Implantable atrial defibrillator Radiofrequency catheter ablation Surgical maze procedure Catheter maze procedure

Rate control (acceptance of arrhythmia and ventricular rate control)

Pharmacological: Antiarrhythmic drugs

Non-pharmacological: Ablate and pace

Reduction of thromboembolic risk

Pharmacological: See fig 3

Non-pharmacological: Obliteration of left atrial appendage Catheter PLAATO procedure (investigational)

Radiofrequency catheter ablation

Ablation of arrhythmogenic foci in the pulmonary veins is effective in 60% of patients, but the risk of recurrence is 30-50% in the first year.w45 Complications of catheter ablation include pulmonary vein stenosis, pericardial effusions, and tamponade.

The surgical maze procedure

The maze procedure is based on the concept that a critical mass of atrial tissue is needed to allow multiple waves of depolarisation to spread.w46 w47 Lines of conduction block are strategically created in the atrial tissue by using incisions, or with newer ablation tools such as microwave, cryothermy, ultrasonography, or radiofrequency energy sources. Follow up of patients at the Cleveland Clinic who underwent the maze procedure found more than 90% of patients to be in sinus rhythm at a mean follow up of three years.w48 The maze procedure is associated with complications and requires open heart surgery. Minimally invasive approaches using percutaneous and surgical techniques are being evaluated.

Implantable atrial defibrillators

The internal atrial defibrillator (IAD) follows from the implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD). It involves transvenous leads in the right atrium and coronary sinus. Conversion rates of up to 98% in patients with drug refractory atrial fibrillation have been achieved.w49 An effective shock needs at least 3 J, but energy as little as 1 J may give considerable discomfort, so the technique is associated with poor patient tolerance.w50 Newer models combine IAD and ICD, allowing termination of both atrial and ventricular arrhythmias.

Pacing for atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation occurs in patients with sick sinus syndrome, and the use of atrial pacing is preferred to ventricular pacing; it is associated with a lower incidence of atrial fibrillation and reversal of atrial remodelling.w51 w52 Atrial based pacing could be effective in preventing episodes that are vagally mediated or related to bradycardia.w53

Ablate and pace

Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of the atrioventricular node is highly effective for drug refractory rate control in atrial fibrillation.w54 Ablating the node produces complete heart block, so a permanent pacemaker is needed to maintain an adequate heart rate. Atrial contractions are not restored, and long term anticoagulation treatment is therefore needed.

Obliteration of the left atrial appendage

In patients with non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation, more than 90% of thrombi form in the left atrial appendage.w55 Closing the left atrial appendage may therefore be an effective way to reduce thromboembolic risk. Surgical closure is recommended only as an adjunctive procedure in patients undergoing mitral valve surgery.w56 However, a new device has been developed that allows percutaneous left atrial appendage transcatheter occlusion (PLAATO procedure) via the transeptal approach.w57 A self expanding nitinol cage is placed under transoesophageal echocardiography guidance and allowed to expand in the left atrial appendage, thus filling it and effectively excluding it from the circulation. This may be appropriate for patients who are not suitable for anticoagulation. Further trials are needed to evaluate its long term safety and efficacy.

Resources for patients

Books

Butler EA. Atrial fibrillation, my heart, the doctors, and me. USA: King of Hearts Publishing, 2000—A vivid account of a patient's experience of atrial fibrillation Larsen HR. Lone atrial fibrillation: towards a cure. Canada: International Health News 2000 Medifocus guidebook: atrial fibrillation. Silver Spring, MD: Medifocus, 2004—A comprehensive book on atrial fibrillation for patients and the general public, updated on an annual basis. Available to purchase and download electronically from www.medifocus.com

Websites

Atrial fibrillation: resources for patients (www.a-fib.com)—A comprehensive website for patients and the general public. It includes personal experiences, discussion forums, and questions for doctors Lone atrial fibrillation forum (www.yourhealthbase.com/lafforum.html)—A forum for sharing personal experiences of lone atrial fibrillation. Provides other useful links and information Atrial fibrillation page (www.members.aol.com/mazern/)—A useful resource for educating patients about the mechanisms of atrial fibrillation and non-pharmacological treatments available St Jude's Medical. AF suppression (www.aboutatrialfibrillation.com)—Provides information about atrial fibrillation, including its scope, symptoms, related diagnostic tests, and treatments

Conclusion

Atrial fibrillation is often associated with comorbidity and carries a high risk of stroke and other vascular complications. Anticoagulation remains the established approach for reducing thrombotic complications but seems to be suboptimal in many cases. Rate control and rhythm control strategies seem to be equally effective for many patients with atrial fibrillation. Novel antiarrhythmic and antithrombotic agents are being evaluated and may have an increasing role in the future management of this common arrhythmia. Box 4 summarises the management of atrial fibrillation.

Supplementary Material

Extra references and three tables are on bmj.com

Extra references and three tables are on bmj.com

Contributors: MBI, AKT, and MF developed the concept of the article. MBI is the primary author. AKT, MF, and GYHL reviewed the manuscript and contributed to all sections.

Competing interests: MBI has no competing interests. AKT and MF are working on an ongoing study of atrial fibrillation funded by Sanofi-Synthelabo and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Sanofi-Synthelabo and Bristol-Myers Squibb are also providing research grants to Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Trust. MF is also on the advisory panel of AstraZeneca on ximelagatran. GYHL has received funding for research, educational symposiums, consultancy, and lecturing from different manufacturers of drugs used for the treatment of atrial fibrillation and thrombosis, including AstraZeneca, who manufacture ximelagatran.

References

- 1.Feinberg WM, Blackshear JL, Laupacis A, Kronmal R, Hart RG. Prevalence, age distribution, and gender of patients with atrial fibrillation: analysis and implications. Arch Intern Med 1995;155: 469-73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruigomez A, Johansson S, Wallander MA, Rodriguez LA. Incidence of chronic atrial fibrillation in general practice and its treatment pattern. J Clin Epidemiol 2002;55: 358-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, Chang Y, Henault LE, Selby JV, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the anticoagulation and risk factors in atrial fibrillation (ATRIA) study. JAMA 2001;285: 2370-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kannel WB, Abbott RD, Savage DD, McNamara PM. Epidemiologic features of chronic atrial fibrillation: the Framingham study. N Engl J Med 1982;306: 1018-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Vaziri SM, D'Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Wolf PA. Independent risk factors for atrial fibrillation in a population-based cohort: the Framingham heart study. JAMA 1994;271: 840-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham study. Stroke 1991;22: 983-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuster V, Ryden LE, Asinger RW, Cannom DS, Crijns HJ, Frye RL, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines and Policy Conferences (committee to develop guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation) developed in collaboration with the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Eur Heart J 2001;22: 1852-923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haissaguerre M, Jais P, Shah DC, Takahashi A, Hocini M, Quiniou G, et al. Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N Engl J Med 1998;339: 659-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai CF, Tai CT, Hsieh MH, Lin WS, Yu WC, Ueng KC, et al. Initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating from the superior vena cava: electrophysiological characteristics and results of radiofrequency ablation. Circulation 2000;102: 67-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hwang C, Karagueuzian HS, Chen PS. Idiopathic paroxysmal atrial fibrillation induced by a focal atr discharge mechanism in the left superior pulmonary vein: possible roles of the ligament of Marshall. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1999;10: 636-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allessie MA, Konings K, Kirchhof CJ, Wijffels M. Electrophysiologic mechanisms of perpetuation of atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol 1996;77: 10-23A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fareh S, Villemaire C, Nattel S. Importance of refractoriness heterogeneity in the enhanced vulnerability to atrial fibrillation induction caused by tachycardia-induced atrial electrical remodeling. Circulation 1998;98: 2202-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lip GYH. Does atrial fibrillation confer a hypercoagulable state? Lancet 1995;346: 1313-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Gelder IC, Crijns HJ, Tieleman RG, Brugemann J, De Kam PJ, Gosselink AT, et al. Chronic atrial fibrillation: success of serial cardioversion therapy and safety of oral anticoagulation. Arch Intern Med 1996;156: 2585-92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Volgman AS, Soble JS, Neumann A, Mukhtar KN, Iftikhar F, Vallesteros A, et al. Effect of left atrial size on recurrence of atrial fibrillation after electrical cardioversion: atrial dimension versus volume. Am J Card Imaging 1996;10: 261-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Consensus Conference on Atrial Fibrillation in Hospital and General Practice. Final consensus statement. Proc R Coll Physicians Edinb 1999;suppl 6: 2-3.

- 17.Albers GW, Dalen JE, Laupacis A, Manning WJ, Petersen P, Singer DE. Antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation. Stroke 2001;119: 194-206S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borgeat A, Goy JJ, Maendly R, Kaufmann U, Grbic M, Sigwart U. Flecainide versus quinidine for conversion of atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm. Am J Cardiol 1986;58: 496-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinez-Marcos FJ, Garcia-Garmendia JL, Ortega-Carpio A, Fernandez-Gomez JM, Santos JM, Camacho C. Comparison of intravenous flecainide, propafenone, and amiodarone for conversion of acute atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm. Am J Cardiol 2000;86: 950-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galve E, Rius T, Ballester R, Artaza MA, Arnau JM, Garcia-Dorado D, et al. Intravenous amiodarone in treatment of recent-onset atrial fibrillation: results of a randomized, controlled study. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996;27: 1079-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Falk RH, Pollak A, Singh SN, Friedrich T. Intravenous dofetilide, a class III antiarrhythmic agent, for the termination of sustained atrial fibrillation or flutter. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997;29: 385-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Gelder IC, Crijns HJ, Van Gilst WH, Verwer R, Lie KI. Prediction of uneventful cardioversion and maintenance of sinus rhythm from direct-current electrical cardioversion of chronic atrial fibrillation and flutter. Am J Cardiol 1991;68: 41-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lau CP, Lok NS. A comparison of transvenous atrial defibrillation of acute and chronic atrial fibrillation and the effect of intravenous sotalol on human atrial defibrillation threshold. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1997;20: 2442-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oral H, Souza JJ, Michaud GF, Knight BP, Goyal R, Strickberger SA, et al. Facilitating transthoracic cardioversion of atrial fibrillation with ibutilide pretreatment. N Engl J Med 1999;340: 1849-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crijns HJ, Gosselink AT, Lie KI. Propafenone versus disopyramide for maintenance of sinus rhythm after electrical cardioversion of chronic atrial fibrillation: a randomized, double blind study. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 1996;10: 145-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naccarelli GV, Dorian P, Hohnloser SH, Coumel P. Prospective comparison of flecainide versus quinidine for the treatment of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation/flutter. Am J Cardiol 1996;77: 53-9A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benditt DG, Williams JH, Jin J, Deering TF, Zucker R, Browne K, et al. Maintenance of sinus rhythm with oral d,l-sotalol therapy in patients with symptomatic atrial fibrillation and/or atrial flutter. Am J Cardiol 1999;84: 270-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.AFFIRM First Antiarrhythmic Drug Substudy Investigators. Maintenance of sinus rhythm in patients with atrial fibrillation: an AFFIRM substudy of the first antiarrhythmic drug. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42: 20-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.