Thyroid hormone binds to nuclear receptors to regulate gene expression and acts in tissues during development and in adult life (1, 2). Thyroid hormone action is regulated at multiple levels, including tissue specific distribution of the receptor isoforms, thyroid hormone receptor (TR) α and TRβ, local activation of the inactive thyroxine (T4) to the biologically active triiodothyronine (T3) by the type 2 5′-deiodinase enzyme (3), and transport of T3 into the cytoplasm by monocarboxylate transporter 8 (Mct8) and other transporters in specific tissues (4). TR isoforms have developmental and tissue-specific distribution (2), with TRα expressed in brain, bone, atria, and skeletal muscle (5). TRβ1 is expressed in liver, cardiac ventricle, and adrenal cortex (6), and TRβ2 is expressed in pituitary, brain, retina, and the inner ear (2). Thyroid hormone is important for normal brain development and function (7). TRα1 has been shown to have a major role during fetal brain development, and TRβ1 has a role in distinct brain regions and in sensory development. Mutation of TRα disrupts the action of T3 on neuronal differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells (8).

Thyroid hormone has long been used for the pharmacologic treatment of conditions in euthyroid individuals, especially lowering cholesterol and weight loss (9). The challenge has been to accomplish these desirable metabolic effects of thyroid hormone without adverse effects on the heart, bone, and other tissues (10). The recognition of differential TR isoform tissue distribution and the development of TR isoform–specific agonists has led to a resurgence of interest in tissue-specific modulation of gene expression for treatment of a range of conditions, especially metabolic and neurologic disorders (10, 11) (Table 1). Sobetirome, originally described with the designation GC1, is a TR agonist with preferential TRβ binding (21). The selectivity of action and favorable side-effect profile, however, relate to both the preference for TRβ isoform binding and also the tissue distribution, with increased distribution to the liver and reduced distribution to the heart, compared with T3 (21). Direct tests of gene expression profiles comparing treatment with sobetirome and T3, within the liver or in vitro in liver cells, however, shows limited differences in the profile of stimulated genes (22). Sobetirome has been effective in preclinical models and in clinical trials for its ability to lower serum cholesterol without substantial adverse effects (13). 3,5-Diiodothyropropionic acid (DIPTA) binds with similar affinity to TRα and TRβ, but in experimental models showed a selective cardiac inotropic function (23). In a clinical trial in patients with congestive heart failure, DIPTA increased cardiac output, but did not reduce symptoms and was poorly tolerated (12). Chronic DITPA treatment was associated with reduced cholesterol, but significant weight loss and an increase in markers of bone turnover (24). Eprotirome (KB2115) has higher affinity for TRβ and has shown good results in phase I and II clinical trials as a monotherapy for hypercholesterolemia with marked reduction of serum low-density lipoprotein (LDL) concentration (15), but was ultimately withdrawn due to adverse action on cartilage in a dog model after chronic administration. Other thyroid hormone analogs, such as MGL-3196 and MB07344, have shown significant LDL reduction as monotherapy or in combination with statins (16, 17). Positive effects on glucose metabolism and weight loss have been reported with thyroid hormone analogs in preclinical studies. In ob/ob mice, KB-141 reduced serum cholesterol and improved glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity (19). GC-24 improved insulin sensitivity and normalized serum triglycerides in rats placed on a high fat diet (20).

Table 1.

Thyroid Hormone Analog Therapeutic Targets

| Compound | TR Isoform Selectivity | Study | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| DITPA | TRβ = TRα | Human clinical trial in congestive heart failure (12) | No improvement in CHF; beneficial effect on LDL and weight reduction |

| Sobetirome (also referred to as GC1) | TRβ > TRα (10-fold) | Preclinical study and clinical trial for hypercholesterolemia (13) | Reduction in LDL, triglyceride, lipoprotein a |

| Induction of ABCD2 in fibroblasts of X-ALD patients (14) | Stimulation of ABCD2 expression | ||

| Eprotirome | TRβ > TRα (22-fold) | Clinical trial hypercholesterolemia (15) | Reduction in LDL, triglyceride, lipoprotein a |

| MB07344 | TRβ > TRα (15-fold) | Animal model study for hyperlipidemia in combination with statin (16) | Synergic effect in lowering cholesterol |

| MGL-3196 | TRβ > TRα (28-fold) | Clinical study for hypercholesterolemia (17) | Reduction in LDL and apolipoprotein B |

| Triac | TRβ > TRα (2-fold to 3-fold) | Mouse model of MCT8 deficiency (18) | Restore neuronal differentiation in mice |

| KB141 | TRβ > TRα (8-fold) | Models of obesity and diabetes (19) | Improved glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity; reduction in body weight |

| GC-24 | TRβ > TRα (40-fold) | Model of diet-induced obesity (20) | Improved glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity |

Abbreviations: CHF, congestive heart failure; DITPA, 3,5 diidothyropropionic acid; LDL, low density lipoprotein; MCT8, monocarboxylate transporter 8; TRIAC, 3,5,3′- triiodothyroacetic acid; X-ALD, X -linked adrenoleukodystrophy.

In this issue of Endocrinology, Hartley et al. (25) demonstrate the efficacy of sobetirome in a mouse model of X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy (X-ALD), a rare disease caused by a mutation of a membrane peroxisome lipid transporter (ABCD1) that leads to the toxic accumulation of C24:0 and C26:0, very long-chain fatty acids (VLCFAs), in the brain and adrenal (26). The clinical presentation varies with respect to age of onset and the tissues involved and ranges from isolated adrenocortical insufficiency and slowly progressive myelopathy to lethal cerebral demyelination, with childhood onset cerebral the most severe. At this time, there are no effective treatments available (26). Various approaches to treatment have been attempted, including Lorenzo's Oil, a dietary supplement that lowers VLCFA levels by inhibiting synthesis (26), and compounds such as bezafibrate that inhibits fatty acid elongation (27).

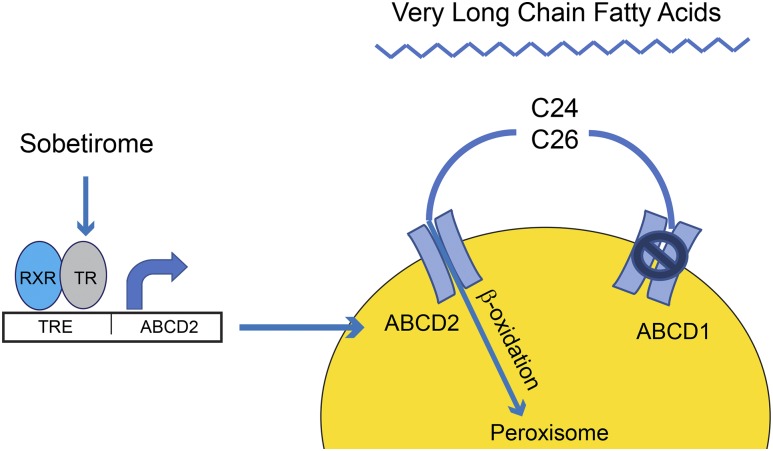

Several previous studies form the basis of the approach used by Hartley et al. (25). Overexpression of ABCD2, which is a homologous peroxisomal lipid transporter, has been shown to compensate for the deficiency of ABCD1 in a mouse model of X-ALD, preventing accumulation of VLCFA in the brain (28) (Fig. 1). Pharmacologic stimulation of the ABCD2 transporter has been attempted with several approaches. The histone deacetylase inhibitor 4-phenylbutyrate stimulates ABCD2 expression and reduced VLCFA in the brain of an X-ALD mouse model, with 6 weeks of dietary 4-phenylbutyrate normalizing C24:0 levels and inducing an 80% reduction of C26:0 (29). The ABCD2 gene promoter is thyroid hormone responsive, and treatment with thyroid hormone upregulates the expression of this membrane lipid transporter in ABCD1 deficient fibroblasts and was shown to require TRβ to mediate this stimulation (30). Finally, sobetirome and CGS 23425, TRβ-selective analogs, were shown to stimulate ABCD2 expression in cell lines and fibroblasts from X-ALD patients (14).

Figure 1.

Sobetirome stimulates peroxisomal β-oxidation of very long-chain fatty acid by upregulating ABCD2. Sobetirome increases expression of a peroxisomal lipid transporter (ABCD2) in cells lacking ABCD1. Upregulation of ABCD2 increases peroxisomal uptake and β-oxidation of C24 and C26 very long-chain fatty acid.

This study by Hartley et al. (25), builds on the previous studies, but utilizes longer term therapy of sobetirome in an animal model and demonstrates a significant action on VLCFA in the adrenal and brain. The authors demonstrate that ABCD2 expression is upregulated with T3 or sobetirome treatment in the fibroblasts of patients with X-ALD as well as the liver and brain of ABCD1 knockout mice, a mouse model of X-ALD (25). They then investigated if the upregulation of ABCD2 results in a reduction of VLCFA levels. X-ALD mice were made hypothyroid and then treated with high-dose T3 or sobetirome. Interestingly, at day 7 and 28, after induction of hyperthyroidism with T3 or sobetirome, the level of VLCFA was significantly reduced in the plasma and adrenal glands of these X-ALD mice but not in the brain. Because of the long turnover of the murine myelin lipid component, the authors speculated that a longer treatment would be necessary to see any changes in the levels of VLCFA in the brain. After 12 weeks, T4/T3 or sobetirome treatment induced, respectively 24% and 17% reduction, of VLCFA in the brain.

Is the modest reduction in brain VLCFA demonstrated in the X-ALD mice by chronic sobetirome treatment relevant for treatment of patients with X-ALD? The mouse model has limitations, as ABCD1 knockout mice do not develop the classic clinical phenotype with respect to neurologic manifestations and, in particular, the cerebral demyelination and inflammation. It is generally accepted, though, that VLCFA accumulation leads to the X-ALD clinical phenotype and the devastating cerebral demyelination, such that even the partial reduction of VLCFA observed with chronic treatment by Hartley et al. (25) in the X-ALD mouse holds promise for a therapeutic action of sobetirome. The reduction of VLCFA was achieved with relatively high concentrations of sobetirome, raising concern for adverse actions on tissues such as the heart and bone. However, therapy of long duration could produce side effects that are unacceptable for treatment targets of weight loss or cholesterol lowering, but are acceptable for X-ALD, a condition which is severe and with very limited treatment options. The side-effect profile of TRβ-selective agonists, such as sobetirome, are favorable with respect to cardiac (21) and bone effects (31), and the off-target effects could potentially be managed with β blockers and bisphosphonates, as is done for patients with thyroid cancer receiving chronic excess thyroid hormone therapy to suppress serum thyrotropin.

Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome (AHDS) is characterized by congenital hypotonia, spasticity, and severe psychomotor delay and is due to a mutation of the thyroid hormone transporter Mct8 (18). The Mct8 gene mutation results in blunted thyroid hormone feedback to thyrotropin, resulting in higher levels of circulating T3 and hypermetabolism, with a high caloric requirement. 3,3′,5-triiodothyroacetic acid, a natural thyroid hormone analog with a slight preferential affinity for TRβ and the capability to be transported into the brain cells independent of Mct8, has been studied in animal models of Mct8 deficiency (18). DITPA does not require Mct8 transporter and has been shown to have brain action in mouse models of Mct8 knockout and for treatment of patients with AHDS (32). Treatment in patients results in normalization of the thyroid tests and reduced caloric requirement, but does not influence the neurologic phenotype. The metabolic actions of thyroid hormone are more readily reversed with thyroid hormone analogs than neurologic deficits.

Sobetirome reduction of VLCFA in the brain of the X-ALD mouse models builds on the previous strategy proposed to treat X-ALD by increasing expression of the alternative transporter, ABCD2 (25). Clinical experience with systemic sobetirome treatment of hypercholesterolemia suggests a favorable side-effect profile, although the dose and duration of therapy that would be required for X-ALD remains to be established. Given the current limitation of X-ALD animal models, with respect to the brain manifestations, only human clinical trials with sobetirome will provide direct answers to the efficacy. Despite the potent actions of thyroid hormone in the brain, especially during development, the experience with other conditions, such as AHDS and even iodine deficiency, is that the more established the disease, the less effective the intervention will be, so early initiation of therapy in X-ALD is likely important. Combination of agents that increase ABCD2 expression with agents that inhibit fatty acid oxidation may also enhance the effectiveness of therapy for X-ALD. These findings may represent an important advancement for treatment of X-ALD, as well as further expanding the spectrum of disorders that can be treated with thyroid hormone analogs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant 1K08DK097295 (to A.M.), NIH Grant RO1DK98576 (to G.A.B.), and Veterans Affairs Merit Review Awards (to G.A.B. and A.M.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AHDS

- Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome

- DIPTA

- 3,5-diiodothyropropionic acid

- LDL

- low-density lipoprotein

- Mct8

- monocarboxylate transporter 8

- T3

- triiodothyronine

- T4

- thyroxine

- TR

- thyroid hormone receptor

- VLCFA

- very long-chain fatty acid

- X-ALD

- X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy.

References

- 1.Brent GA. Mechanisms of thyroid hormone action. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(9):3035–3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng SY, Leonard JL, Davis PJ. Molecular aspects of thyroid hormone actions. Endocr Rev. 2010;31(2):139–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larsen PR, Zavacki AM. The role of the iodothyronine deiodinases in the physiology and pathophysiology of thyroid hormone action. Eur Thyroid J. 2012;1(4):232–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Visser WE, Friesema EC, Visser TJ. Minireview: thyroid hormone transporters: the knowns and the unknowns. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milanesi A, Lee JW, Kim NH, Liu YY, Yang A, Sedrakyan S, Kahng A, Cervantes V, Tripuraneni N, Cheng SY, Perin L, Brent GA. Thyroid hormone receptor α plays an essential role in male skeletal muscle myoblast proliferation, differentiation, and response to injury. Endocrinology. 2016;157(1):4–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang CC, Kraft C, Moy N, Ng L, Forrest D. A novel population of inner cortical cells in the adrenal gland that displays sexually dimorphic expression of thyroid hormone receptor-β1. Endocrinology. 2015;156(6):2338–2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernal J, Guadaño-Ferraz A, Morte B. Thyroid hormone transporters-functions and clinical implications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11(12):690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu YY, Tachiki KH, Brent GA. A targeted thyroid hormone receptor alpha gene dominant-negative mutation (P398H) selectively impairs gene expression in differentiated embryonic stem cells. Endocrinology. 2002;143:2664–2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lamki L, Ezrin C, Koven I, Steiner G. L-thyroxine in the treatment of obesity without increase in loss of lean body mass. Metabolism. 1973;22(4):617–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brenta G, Danzi S, Klein I. Potential therapeutic applications of thyroid hormone analogs. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2007;3(9):632–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baxter JD, Webb P. Thyroid hormone mimetics: potential applications in atherosclerosis, obesity and type 2 diabetes. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8(4):308–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldman S, McCarren M, Morkin E, Ladenson PW, Edson R, Warren S, Ohm J, Thai H, Churby L, Barnhill J, O’Brien T, Anand I, Warner A, Hattler B, Dunlap M, Erikson J, Shih MC, Lavori P. DITPA (3,5-diiodothyropropionic acid), a thyroid hormone analog to treat heart failure: phase II trial veterans affairs cooperative study. Circulation. 2009;119(24):3093–3100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin JZ, Martagón AJ, Hsueh WA, Baxter JD, Gustafsson JA, Webb P, Phillips KJ. Thyroid hormone receptor agonists reduce serum cholesterol independent of the LDL receptor. Endocrinology. 2012;153(12):6136–6144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Genin EC, Gondcaille C, Trompier D, Savary S. Induction of the adrenoleukodystrophy-related gene (ABCD2) by thyromimetics. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;116(1-2):37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ladenson PW, Kristensen JD, Ridgway EC, Olsson AG, Carlsson B, Klein I, Baxter JD, Angelin B. Use of the thyroid hormone analogue eprotirome in statin-treated dyslipidemia. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(10):906–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ito BR, Zhang BH, Cable EE, Song X, Fujitaki JM, MacKenna DA, Wilker CE, Chi B, van Poelje PD, Linemeyer DL, Erion MD. Thyroid hormone beta receptor activation has additive cholesterol lowering activity in combination with atorvastatin in rabbits, dogs and monkeys. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156(3):454–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taub R, Chiang E, Chabot-Blanchet M, Kelly MJ, Reeves RA, Guertin MC, Tardif JC. Lipid lowering in healthy volunteers treated with multiple doses of MGL-3196, a liver-targeted thyroid hormone receptor-β agonist. Atherosclerosis. 2013;230(2):373–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horn S, Kersseboom S, Mayerl S, Müller J, Groba C, Trajkovic-Arsic M, Ackermann T, Visser TJ, Heuer H. Tetrac can replace thyroid hormone during brain development in mouse mutants deficient in the thyroid hormone transporter mct8. Endocrinology. 2013;154(2):968–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bryzgalova G, Effendic S, Khan A, Rehnmark S, Barbounis P, Boulet J, Dong G, Singh R, Shapses S, Malm J, Webb P, Baxter JD, Grover GJ. Anti-obesity, anti-diabetic, and lipid lowering effects of the thyroid receptor beta subtype selective agonist KB-141. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;111(3-5):262–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amorim BS, Ueta CB, Freitas BC, Nassif RJ, Gouveia CH, Christoffolete MA, Moriscot AS, Lancelloti CL, Llimona F, Barbeiro HV, de Souza HP, Catanozi S, Passarelli M, Aoki MS, Bianco AC, Ribeiro MO. A TRbeta-selective agonist confers resistance to diet-induced obesity. J Endocrinol. 2009;203(2):291–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trost SU, Swanson E, Gloss B, Wang-Iverson DB, Zhang H, Volodarsky T, Grover GJ, Baxter JD, Chiellini G, Scanlan TS, Dillmann WH. The thyroid hormone receptor-beta-selective agonist GC-1 differentially affects plasma lipids and cardiac activity. Endocrinology. 2000;141:3057–3064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yuan C, Lin JZ, Sieglaff DH, Ayers SD, Denoto-Reynolds F, Baxter JD, Webb P. Identical gene regulation patterns of T3 and selective thyroid hormone receptor modulator GC-1. Endocrinology. 2012;153(1):501–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pennock GD, Raya TE, Bahl JJ, Goldman S, Morkin E. Cardiac effects of 3,5-diiodothyropropionic acid, a thyroid hormone analog with inotropic selectivity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;263(1):163–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ladenson PW, McCarren M, Morkin E, Edson RG, Shih MC, Warren SR, Barnhill JG, Churby L, Thai H, O’Brien T, Anand I, Warner A, Hattler B, Dunlap M, Erikson J, Goldman S. Effects of the thyromimetic agent diiodothyropropionic acid on body weight, body mass index, and serum lipoproteins: a pilot prospective, randomized, controlled study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(3):1349–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hartley MD, Kirkemo LL, Banerji T, Scanlan TS. A thyroid hormone–based strategy for correcting the biochemical abnormality in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Endocrinology. 2017;158(5):1328–1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berger J, Gartner J. X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy: clinical, biochemical and pathogenetic aspects. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 2006;1763:1721-1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Engelen M, Schackmann MJ, Ofman R, Sanders RJ, Dijkstra IM, Houten SM, Fourcade S, Pujol A, Poll-The BT, Wanders RJ, Kemp S. Bezafibrate lowers very long-chain fatty acids in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy fibroblasts by inhibiting fatty acid elongation. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2012;35(6):1137–1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pujol A, Ferrer I, Camps C, Metzger E, Hindelang C, Callizot N, Ruiz M, Pàmpols T, Giròs M, Mandel JL. Functional overlap between ABCD1 (ALD) and ABCD2 (ALDR) transporters: a therapeutic target for X-adrenoleukodystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13(23):2997–3006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kemp S, Wei HM, Lu JF, Braiterman LT, McGuinness MC, Moser AB, Watkins PA, Smith KD. Gene redundancy and pharmacological gene therapy: implications for X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Nat Med. 1998;4(11):1261–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fourcade S, Savary S, Gondcaille C, Berger J, Netik A, Cadepond F, El Etr M, Molzer B, Bugaut M. Thyroid hormone induction of the adrenoleukodystrophy-related gene (ABCD2). Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63(6):1296–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freitas FR, Moriscot AS, Jorgetti V, Soares AG, Passarelli M, Scanlan TS, Brent GA, Bianco AC, Gouveia CH. Spared bone mass in rats treated with thyroid hormone receptor TR beta-selective compound GC-1. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;285(5):E1135–E1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verge CF, Konrad D, Cohen M, Di Cosmo C, Dumitrescu AM, Marcinkowski T, Hameed S, Hamilton J, Weiss RE, Refetoff S. Diiodothyropropionic acid (DITPA) in the treatment of MCT8 deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(12):4515–4523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]