Abstract

We report two cases of Nicolau syndrome (embolia cutis medicamentosa), a rare complication of injectable medications, both associated with the administration of 20 mg of subcutaneous glatiramer acetate. Both patients required surgical debridement and were subsequently treated conservatively without additional complications. Patient 1 opted to discontinue disease-modifying therapy. Patient 2 continued glatiramer acetate therapy without complications by using other injection sites. These cases highlight the need for prompt investigation of new unusual skin lesions in patients receiving injectable multiple sclerosis treatments (regardless of length of treatment and previous minor cosmetic concerns) and illustrate the clinical distinction between Nicolau syndrome and drug-induced skin necrosis.

Nicolau syndrome (embolia cutis medicamentosa) is a rare iatrogenic complication of injectable medications that can lead to skin necrosis.1 Intramuscular injections have been associated with this phenomenon more often than subcutaneous injections such as glatiramer acetate (GA).2

The spectrum of GA-associated dermatologic events includes localized injection-site reactions (ISRs) with pain, erythema, and induration; less commonly, lipoatrophy and panniculitis; and rarely, skin necrosis.3 Herein, we report two cases of Nicolau syndrome associated with GA therapy. One patient required prompt surgical intervention and wound care, and the other was treated conservatively before eventual wound debridement.

Informed consent was provided by both patients included in this report; Johns Hopkins University institutional review board approval was not required for this report of two cases.

Case 1

A 43-year-old woman diagnosed with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS) 2 years earlier and treated solely with GA developed sharp pain in her left thigh immediately after administering GA. Within several hours, the 3.8-cm2 area became erythematous, swollen, warm, and painful. Lancinating pain continued into the next day. She went to a local urgent care facility and was empirically prescribed cephalexin for presumed cellulitis. During the next 2 days, the lesion became livid and persistently ached, prompting her to visit a primary-care physician, who referred her for surgical consultation. She had already stopped injections after the initial symptoms started. The patient ultimately developed a necrotic lesion with granulation tissue but no signs of infection or large-vessel thrombosis. She underwent surgical debridement followed by conservative wound care. During the following 9 months, the lesion improved (Figure 1). In the meantime, she did not have MS-related clinical activity and chose to discontinue disease-modifying MS therapies, although she is considering starting an oral MS medication.

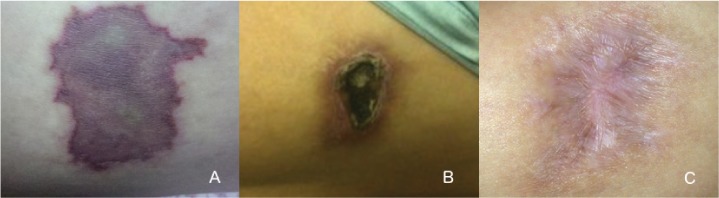

Figure 1.

A, Livid skin lesion on the anterolateral thigh measuring approximately 1.5 × 1.0 cm 5 days after subcutaneous injection with glatiramer acetate. B, Eschar formation 9 weeks after injection. C, Healed scar approximately 9 months after wound debridement.

The patient had not had any previous adverse effects and had never been exposed to other immunomodulatory or immunosuppressive medications. She had no history of environmental or drug allergies. Her medical history included vitamin D insufficiency and migraine headaches. At the time of the ISR, oral vitamin D supplementation was her only additional medication.

Case 2

A 34-year-old woman diagnosed with relapsing-remitting MS at age 30 years after transverse myelitis who was treated solely with GA since age 31 years experienced severe pain in her left anterior thigh immediately after injecting GA. Within hours, erythema and swelling developed. She visited a local urgent care facility and was empirically treated for cellulitis with cephalexin. Pain and swelling continued. Two days later she visited her primary-care physician, who noted the erythematous and now ulcerated lesion and referred her to a wound care center. The lesion (1.0 × 1.1 × 0.3 cm) was managed conservatively with topical wound care and dressing changes. At 2 weeks, an eschar had formed and the wound was debrided. The lesion healed without further complications. Biopsy for histopathologic diagnosis was not performed. She continued GA therapy for several months, using her remaining injection sites.

The patient had not had any previous GA-associated adverse effects and had not been exposed to other immunomodulatory or immunosuppressive medications. Her medical history included hypertension, allergic rhinitis, and an allergy to codeine. At the time of the ISR, amlodipine, cetirizine, and vitamin D supplementation were her only other medications.

One year later, given new signs of deteriorating balance and disease progression, her treatment was changed from GA to natalizumab.

Discussion

Nicolau syndrome is a rare iatrogenic complication of injectable medications (typically intramuscular, although cases have occurred with subcutaneous administration) that is mechanically and immediately related to the injection itself rather than to the composition of the drug administered.1,2,4 It is purportedly associated with microembolization and localized vasopasm of terminal vasculature.2,5 On this basis, it is argued that the drug itself need not be discontinued because the reaction is not fated to recur as a true allergic response; patients have continued GA without further complications even after episodes of necrosis.2,5 There are rare accounts of Nicolau syndrome associated with GA, first reported in 2003.4–8 It can be distinguished from GA-induced skin necrosis on clinical grounds: whereas drug-induced necrosis typically develops gradually at multiple sites with multilocular ulcerative lesions, Nicolau syndrome typically involves immediate localized pain, a livid or violaceous appearance, and palpable swelling within hours of injection. Days later, the site becomes necrotic and, within weeks, develops an eschar. The two cases reported herein fit the latter description, supporting the diagnosis of Nicolau syndrome.

These cases demonstrate that although GA (typically dosed as 20 mg subcutaneously) is generally considered to be well tolerated, new skin lesions should be examined to determine whether they are minor or instead represent a serious reaction. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of three-times-weekly dosed 40-mg GA found that 35% of patients experienced an ISR of any type, with 1% of patients discontinuing treatment for this reason; this trial did not identify any cases of skin necrosis associated with 40-mg GA.9 A literature review did not find any published cases of skin necrosis involving the 40-mg dose, although in principle this rare reaction is still possible based on its purported mechanism.

Common adverse effects of subcutaneous GA injections include mild localized erythema and induration. Lipoatrophy and localized panniculitis have been reported.10 Skin necrosis is more commonly seen with interferon beta, although cases have also been reported with GA.2,11 Least commonly, there have been single case reports of erythema nodosum, Jessner-Kanof lymphocytic infiltration, urticarial vasculitis, and cutaneous CD30+ primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma associated with GA.3

In patients experiencing an atypical ISR, consultation with a dermatologist, a wound care specialist, or possibly a surgeon may be prudent given the potential for permanent scarring. Given the rarity of this condition, there is not a single standard of care, although in reported cases the approach is usually conservative (analgesia, wound care) unless or until necrosis prompts surgical intervention. Clinicians should not assume that such occurrences of new skin abnormalities are simply mild or nuisance problems without having evaluated the lesion in question, especially if the concern is made known by telephone or otherwise not in person.

PracticePoints

Nicolau syndrome is a rare iatrogenic complication of injectable medications (typically intramuscular, although cases have occurred with subcutaneous administration) that is mechanically and immediately related to the injection itself rather than to the composition of the administered drug.

Although injectable medications for MS are usually well tolerated, new skin reactions should be investigated for lividity and ulceration suggesting Nicolau syndrome or drug-induced necrosis.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Kimbrough is a previous participant in the National Institutes of Health T32 Training Program at Johns Hopkins University; has received a previous educational grant from Teva; and has received consulting fees from Medical Logix LLC. Dr. Newsome has served on scientific advisory boards for Biogen and Genentech and has received research support from Biogen, Novartis, and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (paid directly to institution).

References

- 1. Nicolau S. Dermite livedoide et gangreneuse de la fesse, consecutive aux injections intra-muscularies dans la syphilis. Ann Mal Vener. 1925; 20: 321– 329. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Harde V, Schwarz T.. Embolia cutis medicamentosa following subcutaneous injection of glatiramer acetate. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2007; 5: 1122– 1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kluger N, Thouvenot E, Camu W, Guillot B.. Cutaneous adverse events related to glatiramer acetate injection (copolymer-1, Copaxone). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009; 23: 1332– 1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zecca C, Mainetti C, Blum R, Gobbi C.. Recurrent Nicolau syndrome associated with subcutaneous glatiramer acetate injection: a case report. BMC Neurol. 2015; 15: 249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Koller S, Kranke B.. Nicolau syndrome following subcutaneous glatiramer-acetate injection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011; 64: e16– e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gaudez C, Regnier S, Aractingi S, Heinzlef O.. Livedo-like dermatitis (Nicolau's syndrome) after injection of copolymer-1 (glatiramer acetate) [in French]. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2003; 159: 571– 573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Martinez-Moran C, Espinosa-Lara P, Najera L, . et al. Embolia cutis medicamentosa (Nicolau syndrome) after glatiramer acetate injection [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2011; 102: 742– 744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pulido Perez A, Parra Blanco V, Suarez Fernandez R.. Nicolau syndrome after administration of glatiramer acetate [in Spanish]. Neurologia. 2013; 28: 448– 449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Khan O, Rieckmann P, Boyko A, Selmaj K, Zivadinov R; GALA Study Group. . Three times weekly glatiramer acetate in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2013; 73: 705– 713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Edgar CM, Brunet DG, Fenton P, McBride EV, Green P.. Lipoatrophy in patients with multiple sclerosis on glatiramer acetate. Can J Neurol Sci. 2004; 31: 58– 63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Frohman EM, Brannon K, Alexander S, . et al. Disease modifying agent related skin reactions in multiple sclerosis: prevention, assessment, and management. Mult Scler. 2004; 10: 302– 307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]