Abstract

Hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF) belong to the basic helix loop helix–PER ARNT SIM (bHLH-PAS) family of transcription factors that induce metabolic reprogramming under hypoxic condition. The phylogenetic studies of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) sequences across different organisms/species may leave a clue on the evolutionary relationships and its probable correlation to tumorigenesis and adaptation to low oxygen environments. In this study, we have aimed at the evolutionary investigation of the protein HIF-1α across different species to decipher their sequence variations/mutations and look into the probable causes and abnormal behaviour of this molecule under exotic conditions. In total, 16 homologous sequences for HIF-1α were retrieved from the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Sequence identity was performed using the Needle program. Multiple aligned sequences were used to construct the phylogeny using the neighbour-joining method. Most of the changes were observed in oxygen-dependent degradation domain and inhibitory domain. Sixteen sequences were clustered into 5 groups. The phylogenetic analysis clearly highlighted the variations that were observed at the sequence level. Comparisons of the HIF-1α sequence among cancer-prone and cancer-resistant animals enable us to find out the probable clues towards potential risk factors in the development of cancer.

Keywords: Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), hypoxia, phylogeny, oxygen-dependent degradation domain, cancer resistance

Introduction

High proliferation and less vasculature are features under hypoxia in most of the solid tumours. Hypoxic phenotype is the aggressiveness of the tumour with poor prognostic effect.1 Tumour tissues are adapted to this condition with metabolic reprogramming with the expression of hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs). Hypoxia-inducible factors belong to the bHLH-PAS family of transcription factors that induce metabolic reprogramming under hypoxic condition.2 Hypoxia-inducible factor is a heterodimer of HIF-α (containing 826aa) and HIF-β (containing 824aa) subunits. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α exists in 3 isoforms, namely, HIF-1α, HIF-2α, and HIF-3α. The HIF-1β subunits are also known as aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear transporters (ARNTs). The ARNTs are ubiquitously expressed in cells and are stable under normoxic conditions. Recent studies have shown that ARNT level is influenced by hypoxia, and it depends on the cell type.3 However, the HIF-1α subunits are sensitive to oxygen and undergo oxygen-dependent proteasomal degradation, which is regulated by 2 different mechanisms. The first mechanism involves prolyl hydroxylase 2 (PHD2) that adds hydroxyl groups to proline residues (at 402 and 564) present on the oxygen-dependent degradation domain (ODD) of HIF-1α. Von Hippel-Lindau tumour suppressor protein (pVHL) recognizes and binds to the hydroxylated proline residues and directs HIF-1α for proteasomal degradation by interacting with proteasomal E3 ligase complex. Another complementary mechanism which regulates HIF-1α level is factor inhibiting HIF (FIH). It is an asparagine hydroxylase enzyme that adds hydroxyl group to asparagine residue (803) present in C-terminal transactivation domain (C-TAD) of HIF-1α and prevents the interaction with CBP (CREB-binding protein) and p300 transcriptional coactivators, which also promotes proteasomal degradation of HIF-1α.4–6

Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α has a half-life of less than 5 minutes under normoxic conditions4 and is involved in foetal and postnatal physiology.7 However, under hypoxic conditions, HIF-1 and HIF-2α help in developing resistance to chemotherapy and radiotherapy due to downstream effects.5,6,8–10 The HIF-1α plays a major part in the adaptation of solid tumour to low oxygen levels1 that exists at high altitude11 and deep aquatic and subterranean environments,12 as its lifetime increases to 8 minutes and develops stability.11 Hence, in this study, we have aimed at the evolutionary investigation of the protein HIF-1α across different species to decipher their sequence variations/mutations and investigate the probable causes and abnormal behaviour of this molecule under exotic conditions.

The phylogenetic studies of HIF-1α sequences across different organisms/species may throw light on the evolutionary correlations to tumorigenesis and adaptation to low oxygen environments. This understanding may also aid in developing novel strategies to combat cancer while exploring approaches to enhance the efficacy of radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

Materials and Methods

Sequencing analysis

The protein sequence of human HIF-1α (hHIF-1α; isoform 1) was retrieved from Universal Protein Resource (UniProt),13 which contained 826 amino acids. To examine the occurrence and evolutionary correlations of HIF-1α in 16 different species, namely, chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes: JAA40616.1), Sumatran orangutan (Pongo abelii: NP_001126975.1), rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta: H9ET32), crab-eating macaque (Macaca fascicularis: NP_001270825.1), dog (Canis lupus familiaris: NP_001274092.1), yak (Bos grunniens: Q0PGG7.1), cow (Bos taurus: NP_776764.2), Tibetan antelope (Pantholops hodgsonii: AAX89137.1), goat (Capra aegagrus hircus: NP_001272657.1), blind mole-rat (BMR; Nannospalax judaei: CAG29396.1), rat (Rattus norvegicus: NP_077335.1), mouse (Mus musculus: AAC53461.1), naked mole-rat (NMR; Heterocephalus glaber: NP_001297196.1), naked carp (Gymnocypris przewalskii: AAW69834.1), and zebrafish (Danio rerio: AAQ91619.1), respectively. Global alignment (Needle) with BLOSUM62 (Gap open penalty 10, Gap extend penalty 2)14–16 and multiple alignment via the tool MultAlin17 were performed. These sequences were selected on the basis of hypoxic-adapted and normoxic animals.

Human HIF-1α has 10 domains, namely, bHLH (17–70), PAS-A (85–158), PAS-B (228–298), PAS-C (302–345), ODD (401–603), N-terminal VHL recognition site (380–417), C-terminal VHL recognition site (556–572), inhibitory domain (ID; 576–785), N-terminal transactivation domain (N-TAD; 531–575), and C-TAD (786–826), respectively. Hence, domain-wise comparisons of hHIF-1α with all other organisms were also performed. The alignments were manually curated to remove poorly aligned regions. The output was studied for the position-wise conservation and variations/mutations of amino acids across all the 10 domains of HIF-1α, which are depicted in Figures 1 to 3. Multiple sequence alignment of all 16 protein sequences was deduced using blosum62 with default parameters to observe the various conserved domains across evolution (Corpet1988). The same is also illustrated in Figures 1 to 3.

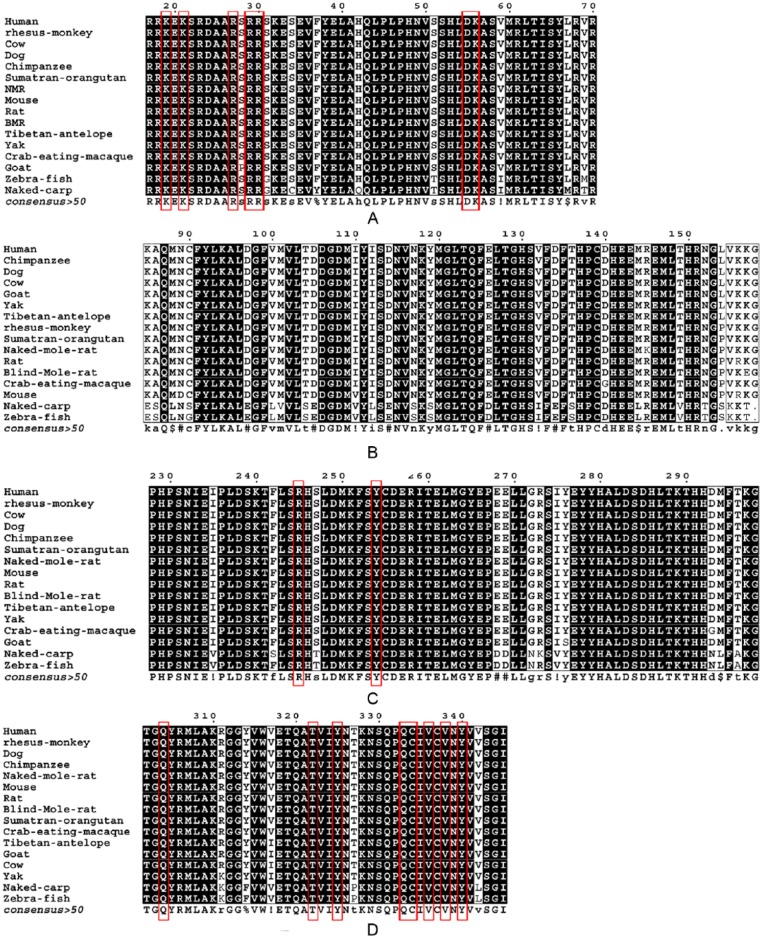

Figure 1.

Multiple sequence alignment. (A) bHLH domain. The DNA-interacting basic amino acids K21, R29, K19, R30, R27, D55, and K56 are highlighted in red.18 (B) PAS-A, (C) PAS-B, and (D) PAS-C. PAS-B is involved in interaction with aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear transporter (ARNT) and HSP90. Residues interacting with PAS-B and ARNT were highlighted in red. PAS-C also includes residues interacting with ARNT as mentioned in crystal structure PDB ID (4H6J), and it is highlighted in red.

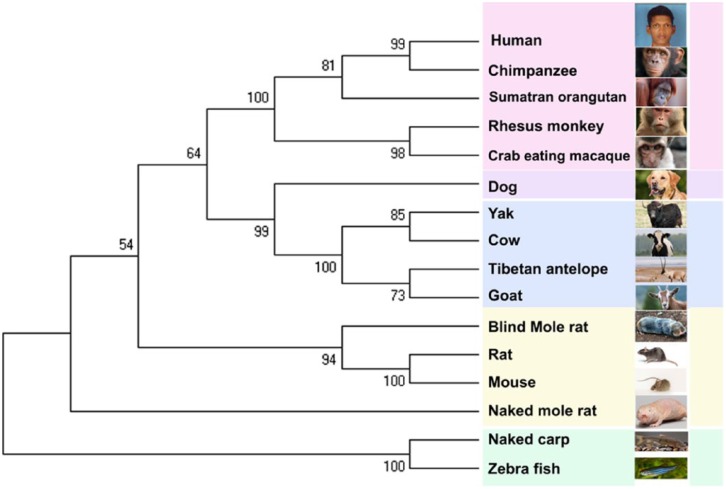

Figure 3.

Multiple sequence analysis of (A) inhibitory domain and (B) C-terminal transactivation domain (C-TAD). There are 2 binding sites in C-TAD. Site 1 in human hypoxia-inducible factor-1α carboxy-terminal activation domain encompasses residues 795 to 806 and contains the hydroxylated asparagine (N803), and site 2 includes residues 812 to 823 and shows only weak binding independent of site 1. These sites are highlighted in green.

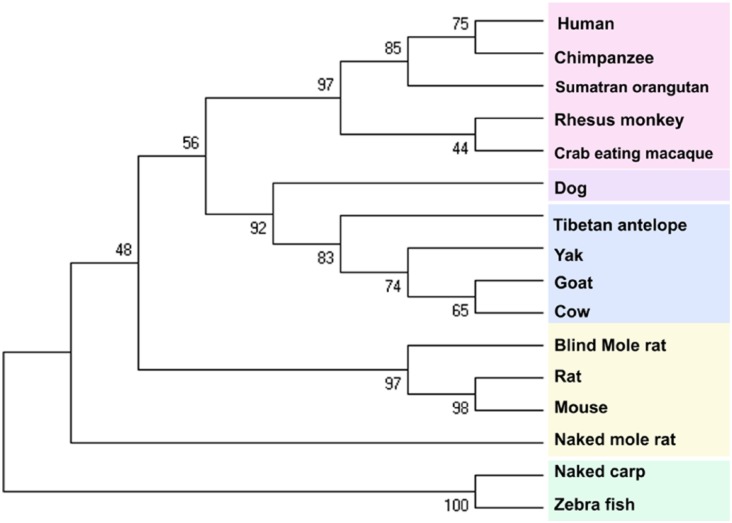

Phylogenetic analysis

The 16 sequences were then used for phylogenetic inferences and evolutionary trees for respective domains of HIF-1α. The output was constructed with MEGA 6.019 and is highlighted in Figure 4. The bootstrap consensus tree inferred from 1000 replicates is taken to represent the evolutionary history of the taxa analysed.20 The neighbour-joining method was used to infer the evolutionary history.21 The bootstrap (value 100) was repeated 1000 times to generate consensus. The branches that are not reproduced less than 50% of the time during bootstrap were collapsed. Poisson correction method was used to compute the evolutionary distances.22 All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated.

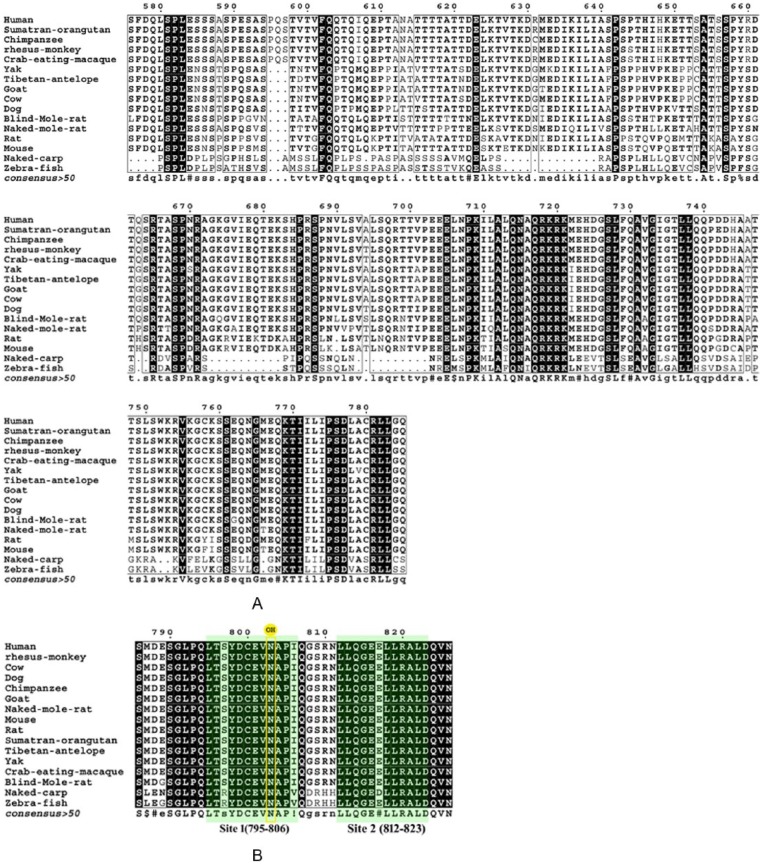

Figure 4.

Evolutionary relationships of taxa for hypoxia-inducible factor-1α of selected organisms.

Results

This study was aimed at deciphering the amino acid variation and phylogenetic relations across the 16 orthologs of HIF-1α. The identities between the sequences were calculated with reference to hHIF-1α. The tabulated results are presented in Supplementary Table 1. Most species exhibit lower identity values for the ODD and IDs, respectively. The values in Supplementary Table 1 highlight that the variations across all domains are maximum for aquatic fishes, naked carp, and zebrafish, respectively. Similar results were exhibited during domain-wise comparison via multiple sequence alignment. The conservation of functional sites in the bHLH domain of HIF-1α was observed across all species considered for the study. Apart from the DNA-binding residues, which were highly conserved, the changes were observed as in Figure 1A. The DNA-interacting basic amino acids, namely, K21, R29, K19, R30, R27, D55, and K56,18 appear to be conserved across the 16 species, indicating that DNA-binding function is intact. Maximum difference was observed in naked carp, which exhibits the following polymorphisms with respect to the hHIF-1α. The classical changes S31C, F34Y, H42Q, S51T, V59I, L67M, and V69T were, respectively, observed in the bHLH domain of naked carp. Similarly, in the PAS-A domain, permissible substitutions such as K85E, A86S, V100L, T104S, D105E, I112L, D114E, N117S, Y119S, E126D, V132I, D134E, T136S, M144L, T149V, N152T, L154S, V155K, and K157T were observed in both naked carp and zebrafish, with respect to hHIF-1α. The heterodimerization of HIF-1α with ARNT is crucial for its transactivity. PAS domains of these 2 proteins play key roles in heterodimerization. As Bersten et al23 have highlighted in his review, the PAS-A domain is less accessible to small and other sensory molecules than the PAS-B. These polymorphisms found in PAS-A may affect the overall activity of HIF-1α. It is well known that PAS-B is the key domain that establishes protein-protein interaction with ARNT and HSP90.24,25 Residues interacting with ARNT were conserved across the 16 selected sequences. However, with PAS-B exhibiting changes, it might affect HSP90 interaction.

Most of the changes in PAS-B domain were observed in naked carp and zebrafish. I235V, S247T, E268D, E269D, G272N, I275V, M294L, and T296A substitutions were found in both naked carp and zebrafish. PAS-C showed the following changes, namely, R311K polymorphism in naked carp, zebrafish, and yak, respectively. Substitutions such as Y314F, T327P, and V342L were observed in naked carp and zebrafish. N-terminal VHL recognition site of hHIF-1α also shows the following changes with respect to naked carp, which denote interesting substitutions, namely, S380P, E381M, D382K, T383N, S384L, S385D, K392E, D395E, and L399V. Similarly, the changes E381L, D382E, T383S, S385T, E393D, P394S, and T407A are seen in zebrafish. Similarly, interesting mutations, namely, T407I and G414S, were observed in NMR. S385C was the other interesting polymorphism reflected in mouse, rat, and BMR, respectively.

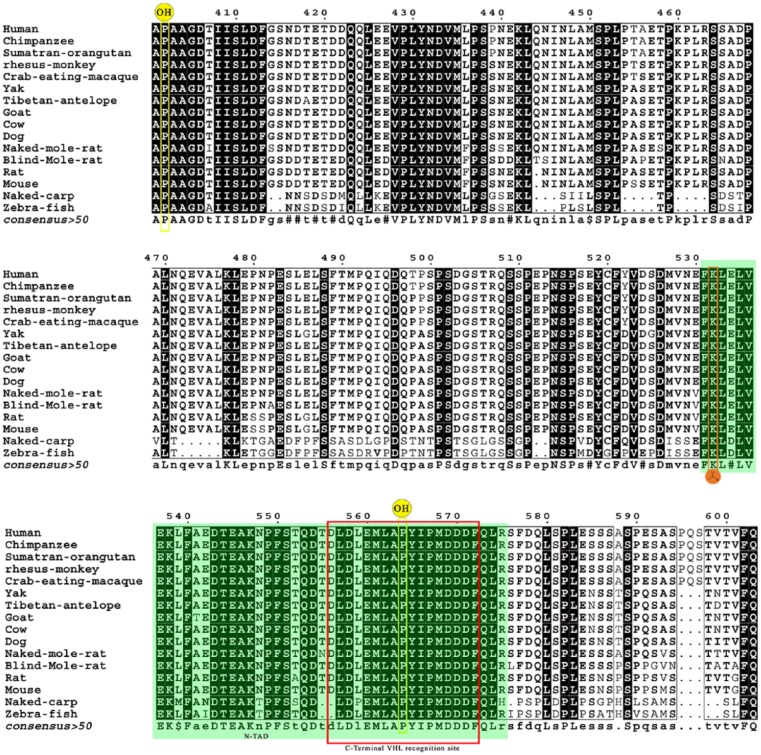

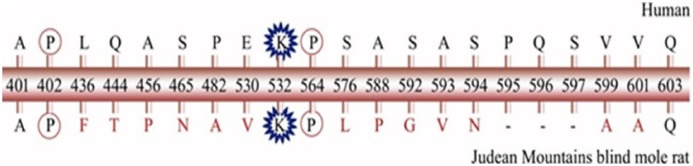

The ODD exhibits notable changes compared with other domains across all the 16 species. The posttranslational modification residues such as P402, K532, and P564 are all conserved across the species (Figure 2). However, a critical change L559P has been observed in the binding site of HIF-1α, which is crucial for PHD2 interaction, which is seen in naked carp. Remaining binding site residues, namely, M568, D571, F572, P567, M561, E560, A563, Y565, P564, I566, L562, L574, Q573, and D570,26 appear well conserved across rat, mouse, humans, and BMR. The N-TAD (which is an integral part of ODD) shows E534D, L539M, E542 N548T, T552S, L559P, and R575H polymorphisms in naked carp. Interesting changes such as A541T in goat, T555N in NMR, T552A in rat, and E534D, E542I, and N548I in zebrafish were observed.

Figure 2.

Multiple sequence alignment of oxygen-dependent degradation domain. Hydroxylation sites P402 and P564 are highlighted in yellow. The acetylation site (K532) is shown in orange red. The N-terminal transactivation domain is shown in green, and the C-terminal VHL recognition site is shown in red box.

The ID shows huge variations, and the same are depicted in Figure 3A. The C-TAD shows the following changes, namely, M787L, D788E, S797R, G808D, S809R, R810H, and N811H in zebrafish and naked carp, respectively. Furthermore, E789G is also found in both BMR and zebrafish.

The regulation and half-life of the protein are dependent on the hydroxylation of proline residues at 402 and 564 by the PHD2 under normoxic condition. The domain that includes these residues is called ODD. The hydroxylated residues were recognized by the pVHL and facilitated the ligation with proteasomal complex.1 Thus, recognition by pVHL is also a major factor towards the HIF-1α turnover. There are lots of changes in N-terminal VHL recognition site of zebrafish and naked carp. The rodents except NMR show S385C substitution. C-terminal VHL recognition site possesses 2 binding sites. Site 1 from 560 to 567 (EMLAHypYIP)4 is well conserved. But in site 2, containing residues (DFQLRSF)4 from 571 to 577, the following changes are observed. R575H, S576P, and F577S substitutions are observed in naked carp. S576I and F577P are found in zebrafish. In BMR, S576L is the change seen. These variations in VHL binding region may not render the VHL-mediated degradation of HIF-1α and increase the stability of protein even under normoxic condition. This may be the probable reason for BMR having a higher level of HIF-1α under hypoxic conditions than normal rats.12 The main regulatory domain is exhibiting good conservation of critical hydroxylation sites (P402 and P564). The binding site (L559, M568, D571, F572, P567, M561, E560, A563, Y565, P564, I566, L562, L574, Q573, and D570)26 of ODD to PHD2 is also well conserved. Acetylation of K532 facilitates the interaction of HIF-1α with VHL, and this site is also well conserved. Interestingly, only the naked carp showed changes in L559P. Naked carp is a hypoxic-adapted fish; this change may increase the stability of HIF-1α by deviating interaction of ODD with PHD2. The C-TAD is a major domain involved in transactivity. The hydroxylation at N803 by FIH prevents its interaction with coactivator. So, any change in the interaction site of C-TAD will affect the regulation of transactivity. There are 2 binding sites in C-TAD. Site 1 in hHIF-1α carboxy-terminal activation domain encompasses residues 795 to 806 and contains the hydroxylated asparagine. Naked carp and zebrafish show S797R I806V mutations in this site. Site 2 includes residues 812 to 823 and shows only weak binding independent of site 1. E817D substitution is found in site 2 of naked carp. The ID is a stretch domain (576–785) that represses the transactivity of HIF-1α. There are lots of changes observed in this domain as illustrated in Figure 3A, which depicts close to 50% variations among naked carp, BMR, zebrafish, and hHIF. The removal of this particular domain increases the transactivity of HIF-1α.27

The phylogenetic analysis clearly highlighted the variations that were observed at the sequence level of HIF-α. Figure 4 indicates that the 16 sequences are clustered into 5 groups. Naked carp and zebrafish standout as an independent cluster, exhibiting significant differences across the set under study. The aquatic creatures, rodents, carnivore (dog), even-toed ungulate, and higher primates are grouped separately. The formation of each clade in the phylogenetic tree (Figure 4) may be due to adaptations by different organisms to their habitats. Even though humans and chimpanzee share the same ancestral branch, the ODD is crucial for determining the half-life of HIF-1α; different organisms may have diverged according to the natural selection (Figure 5). Alignment of sequences showed critical replacements in the ODD. This is evidenced by the phylogenetic distance between the normoxic animals such as human beings and hypoxic animals such as Judean Mountains blind-mole rat. The taxa result infers that there is a clear divergence in HIF-1α protein as it gets evolved. All organisms were grouped out from rodents, zebrafish, and naked carp. From the phylogenetic analysis, we conclude that the variations in the different domains of HIF-α provide vital clues for plausible stabilization of this key molecule under hypoxic and normoxic conditions.

Figure 5.

Phylogeny of the oxygen-dependent degradation domain. The tree shows similar trend in group formation like the tree for entire hypoxia-inducible factor-1α. Shuffle is only observed in the group of even-toed ungulates.

Discussion

We have found significant changes in residues belonging to specific domains of HIF-1α protein and vital clues to appreciate the evolutionary variations. The oxygen-dependent hydroxylation of ODD and its recognition by VHL are crucial steps in HIF-1α half-life and activity. Changes found in this domain may enhance or decrease the activity of HIF-1α. These variations in VHL binding region may not render the VHL-mediated degradation of HIF-1α and increase the stability of protein even under normoxic condition. This may be the possible reason for BMR having a higher level of HIF-1α under hypoxic conditions than normal rats12; several changes were observed in ODD with respect to BMR (Figure 6). Furthermore, the effect of observed changes in N-terminal VHL recognition site and C-terminal VHL recognition site is not known. Particularly in site 2 from 571 to 577 (DFQLRSF), changes observed may be restraining the ODD binding to VHL in naked carp and zebrafish. But these changes are not prominent in either cancer-resistant animals such as BMR and NMR or cancer-prone animals such as humans, mouse, and rat.

Figure 6.

Correlation of changes in human hypoxia-inducible factor-1α oxygen-dependent degradation domain with respect to blind-mole rat. The critical residues such as P402, P564, and K532 are well conserved.

Conclusions

This study is an attempt to appreciate the evolutionary changes of protein HIF-1α and the detailed sequence variations across the set of species considered. Key substitutions in the oxygen-dependent hydroxylation of the ODD and the consequence of the same towards its recognition to VHL enable us to explain its criticality with respect to HIF-1α half-life and its activity. Comparisons of the HIF-1α sequence among cancer-resistant animals, such as BMR and NMR, and cancer-prone animals, such as human, mouse, and rat, suggest derivation of probable clues towards potential risk factors for cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sir M Visvesvaraya Institute of Technology for kind support during the work and also thanks to Vijay Radhakrishan.

Footnotes

PEER REVIEW: Five peer reviewers contributed to the peer review report. Reviewers’ reports totalled 1411 words, excluding any confidential comments to the academic editor.

FUNDING: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions

JP, CGJ, DJK, and HGN conceived and designed the experiments. DJK and HGN analysed the data. CGJ and JP wrote the first draft of the manuscript. JP, CGJ, DJK, and HGN contributed to the writing of the manuscript. CGJ, DJK, and HGN agree with manuscript results and conclusions. JP, CGJ, DJK, and HGN jointly developed the structure and arguments for the paper. CGJ, DJK, and HGN made critical revisions and approved the final version. All authors reviewed and approved of the final manuscript

REFERENCES

- 1.Brahimi-Horn MC, Chiche J, Pouysségur J. Hypoxia and cancer. J Mol Med. 2007;85:1301–1307. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0281-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang GL, Jiang BH, Rue EA, Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:5510–5514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mandl M, Depping R. Hypoxia-inducible aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT) (HIF-1β): is it a rare exception? Mol Med. 2014;20:215–220. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2014.00032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lisy K, Peet DJ. Turn me on: regulating HIF transcriptional activity. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:642–649. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cairns Rob A, Harris IS, Mak TW. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:85–95. doi: 10.1038/nrc2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Staab A, Loeffler J, Said HM, et al. Effects of HIF-1 inhibition by chetomin on hypoxia-related transcription and radiosensitivity in HT 1080 human fibrosarcoma cells. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:1471–2407. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Semenza GL. HIF-1: mediator of physiological and pathophysiological responses to hypoxia. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88:1474. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.4.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baumann R, Depping R, Delaperriere M, Dunst J. Targeting hypoxia to overcome radiation resistance in head & neck cancers: real challenge or clinical fairytale? Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2016;16:751–758. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2016.1192467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertout JA, Majmundar AJ, Gordan JD, et al. HIF2α inhibition promotes p53 pathway activity, tumor cell death, and radiation responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14391–14396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907357106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhatt RS, Landis DM, Zimmer M, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-2α: effect on radiation sensitivity and differential regulation by an mTOR inhibitor. BJU Int. 2008;102:358–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07558.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qiu Q, Zhang G, Ma T, et al. The yak genome and adaptation to life at high altitude. Nat Genet. 2012;44:946–949. doi: 10.1038/ng.2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shams I, Avivi A, Nevo E. Hypoxic stress tolerance of the blind subterranean mole rat: expression of erythropoietin and hypoxia-inducible factor 1α. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9698–9703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403540101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Apweiler R, Bairoch A, Wu CH, et al. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D158–D169. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rice P, Longden I, Bleasby A. EMBOSS: the European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite. Trends Genet. 2000;16:276–277. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li W, Cowley A, Uludag M, et al. The EMBL-EBI bioinformatics web and programmatic tools framework. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W580–W584. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McWilliam H, Li W, Uludag M, et al. Analysis tool web services from the EMBL-EBI. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:W597–W600. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corpet F. Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchical clustering. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:10881–10890. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.22.10881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu D, Potluri N, Lu J, Kim Y, Rastinejad F. Structural integration in hypoxia-inducible factors. Nature. 2015;524:303–308. doi: 10.1038/nature14883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zuckerkandl E, Pauling L. Evolutionary divergence and convergence in proteins. In: Bryson V, Vogel HJ, editors. Evolving Genes and Proteins. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1995. pp. 97–166. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bersten DC, Sullivan AE, Peet DJ, Whitelaw ML. bHLH-PAS proteins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:827–841. doi: 10.1038/nrc3621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cardoso R, Love R, Nilsson CL, et al. Identification of Cys255 in HIF-1α as a novel site for development of covalent inhibitors of HIF-1α/ARNT PasB domain protein-protein interaction. Protein Sci. 2012:211885–1896. doi: 10.1002/pro.2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katschinski DM, Le L, Schindler SG, Thomas T, Voss AK, Wenger RH. Interaction of the PAS B domain with HSP90 accelerates hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha stabilization. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2004;14:351–360. doi: 10.1159/000080345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chowdhury R, McDonough MA, Mecinović J, et al. Structural basis for binding of hypoxia-inducible factor to the oxygen-sensing prolyl hydroxylases. Structure. 2009;17:981–989. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang B-H, Zheng JZ, Leung SW, Roe R, Semenza GL. Transactivation and inhibitory domains of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha: modulation of transcriptional activity by oxygen tension. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19253–19260. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.31.19253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.