Xia et al. show that EGF receptor activation results in the binding of the RNF8 forkhead-associated domain to pyruvate kinase M2-phosphorylated histone H3-T11, leading to histone H3 polyubiquitylation and degradation and subsequent gene expression for tumor cell glycolysis and proliferation.

Abstract

Disassembly of nucleosomes in which genomic DNA is packaged with histone regulates gene expression. However, the mechanisms underlying nucleosome disassembly for gene expression remain elusive. We show here that epidermal growth factor receptor activation results in the binding of the RNF8 forkhead-associated domain to pyruvate kinase M2–phosphorylated histone H3-T11, leading to K48-linked polyubiquitylation of histone H3 at K4 and subsequent proteasome-dependent protein degradation. In addition, H3 polyubiquitylation induces histone dissociation from chromatin, nucleosome disassembly, and binding of RNA polymerase II to MYC and CCND1 promoter regions for transcription. RNF8-mediated histone H3 polyubiquitylation promotes tumor cell glycolysis and proliferation and brain tumorigenesis. Our findings uncover the role of RNF8-mediated histone H3 polyubiquitylation in the regulation of histone H3 stability and chromatin modification, paving the way to gene expression regulation and tumorigenesis.

Introduction

In the eukaryotic nucleus, genomic DNA is packaged into chromatin by forming nucleosomes. Each nucleosome core particle consists of a histone octamer wrapped by 146 base pairs of DNA (Luger et al., 1997). A histone octamer is composed of two copies each of the core histones H2A, H2B, H3, and H4. The histone tails protrude from the nucleosome and are subjected to a wide array of covalent modifications, including ubiquitylation, phosphorylation, methylation, acetylation, sumoylation, and ADP ribosylation (Strahl and Allis, 2000). These posttranscriptional modifications coordinately regulate the chromatin structure, which affects the biological processes of gene expression, DNA replication, and DNA damage response (Chi et al., 2010).

Ubiquitylation is a sequential ATP-dependent enzymatic action of E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme, E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, and E3 ligase (Lu and Hunter, 2009; Bassermann et al., 2014). Proteins can be monoubiquitylated or polyubiquitylated through internal lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, and K63) or the N-terminal methionine (Clague and Urbé, 2010; Behrends and Harper, 2011). Polyubiquitylation via K48 or K11 commits the substrate to degradation by the 26S proteasome, whereas monoubiquitylation or K63-linked polyubiquitylation specifies nonproteolytic fates for the substrate (Bassermann et al., 2014). Histone ubiquitylation and other types of posttranslational modifications, including histone phosphorylation, methylation, and acetylation, can cross-regulate each other (Sun and Allis, 2002; Latham and Dent, 2007). Monoubiquitylation of histone H2A, H2B, H3, H4, and H1 and the histone variants H2AX, H2AZ, and Cse4, which is largely associated with transcription regulation, gene silencing, and DNA repair, has been intensively studied (Zhang, 2003; Osley et al., 2006; Weake and Workman, 2008). Non–chromatin-bound histone H3 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is degraded in a Rad53 kinase– and ubiquitylation-dependent manner with unclarified physiological consequences (Singh et al., 2009). However, whether eukaryotic chromosomal histone is regulated by proteasome-dependent degradation, the molecular mechanism underlying this regulation, and the role of this regulation in gene expression and tumor development are poorly understood.

In this study, we showed that epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor (EGFR) activation resulted in the binding of the RNF8 forkhead-associated (FHA) domain to PKM2-phosphorylated histone H3-T11, leading to histone H3 polyubiquitylation at K4, dissociation of histones from chromatin, and subsequent nucleosome disassembly and degradation of histone H3. RNF8-mediated nucleosome disassembly promoted the binding of RNA polymerase II to the promoter regions of MYC and CCND1 and enhanced the expression of c-Myc and cyclin D1, cell proliferation, and tumorigenesis.

Results

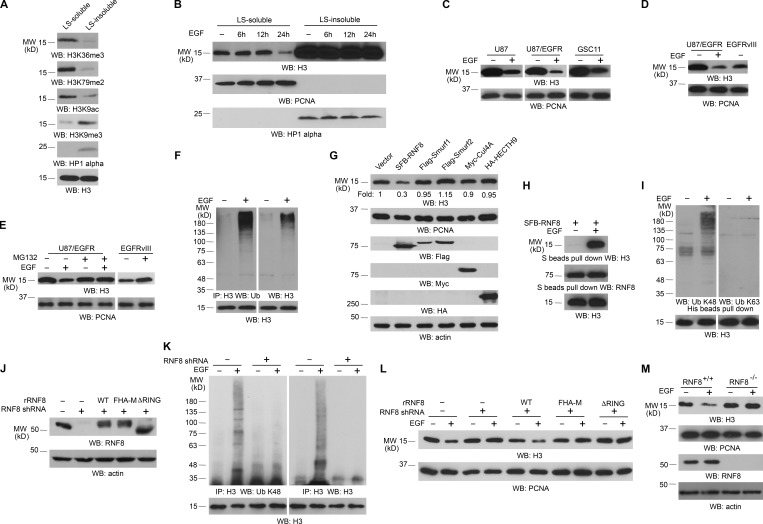

RNF8 regulates EGF-induced polyubiquitylation and degradation of histone H3

To determine whether growth factor receptor activation has any effect on the expression of histone H3, which is important for gene expression (Chi et al., 2010), we used a previously established approach to extract nucleosomes enriched in transcriptionally active chromatin regions (Rocha et al., 1984; Sun et al., 2007; Henikoff et al., 2009). In line with previous studies (Rocha et al., 1984; Sun et al., 2007; Henikoff et al., 2009), transcriptionally active chromatin were enriched in low salt (LS)–soluble but not LS-insoluble fractions of chromatin fragments of U251 glioblastoma (GBM) cells; this was demonstrated by high levels of transcriptional active markers including H3K36me3, H3K79me2, H3K9 acetylation in the LS-soluble fraction and H3K9me3 and HP1 α heterochromatin markers mainly in the insoluble fraction (Fig. 1 A; Maison and Almouzni, 2004; Barski et al., 2007; Steger et al., 2008; Wagner and Carpenter, 2012; Yang et al., 2012b). Quantification analysis of an equal volume of two fractions showed that the amount of histone H3 in LS-soluble fraction was much lower than that in the insoluble fraction (Fig. S1 A). Of note, prolonged EGF treatment significantly reduced histone H3 protein level in LS-soluble, but not LS-insoluble, chromatin fractions (Fig. 1 B). Similar results were also observed in U87 and EGFR-overexpressed U87 (U87/EGFR) GBM cells and GSC11 human primary GBM cells (Fig. 1 C). In addition, U87 cells expressing constitutively active EGFRvIII mutant, which lacks 267 amino acids from its extracellular domain and is commonly found in GBM as well as in breast, ovarian, prostate, and lung carcinomas (Kuan et al., 2001), had significantly lower levels of histone H3 expression than did U87/EGFR cells without EGF treatment (Fig. 1 D). Furthermore, EGF-induced histone H3 down-regulation was also detected in MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells and A431 human epidermoid carcinoma cells (Fig. S1 B). As expected, EGF-induced histone H3 down-regulation was blocked by pretreatment with AG1478, an EGFR inhibitor (Fig. S1 C). Given that EGF treatment or expression of EGFRvIII increased cell proliferation (Yang et al., 2012a,b), these results indicated that EGFR activation leads to histone H3 down-regulation in transcriptionally active chromatin regions in different cell and tumor types, which correlates with increased cell proliferation.

Figure 1.

RNF8 regulates EGF-induced polyubiquitylation and degradation of histone H3. Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation (IP) analyses were performed with the indicated antibodies. WB, Western blot. (A) Chromatin extracts of U251 cells were separated into LS-soluble and LS-insoluble fractions, and an equal amount of H3 was loaded. (B) U251 cells were treated with or without EGF for the indicated time. Chromatin extracts were separated into an equal volume of LS-soluble and LS-insoluble fractions. (C) The indicated cells were treated with or without 100 ng/ml EGF for 24 h. The LS-soluble chromatin extracts were prepared. (D) Immunoblotting analyses of U87/EGFR treated with or without 100 ng/ml EGF for 24 h and U87/EGFRvIII cells were performed with the indicated antibodies. The LS-soluble chromatin extracts were prepared. (E) U87/EGFR cells were pretreated with or without 25 µM MG132 for 30 min before 100 ng/ml EGF stimulation for 24 h. MG132 was incubated with the cells for 8 h and removed to avoid cell death. U87/EGFRvIII cells were treated with or without 25 µM MG132 for 8 h, followed by incubation without MG132 for 16 h. LS-soluble chromatin extracts were prepared. (F) U251 cells were treated with or without 100 ng/ml EGF in the presence of 25 µM MG132 for 6 h. The cell extracts for ubiquitylation assay were prepared. (G) The indicated E3 ligases were transfected with a plasmid expressing EGFRvIII in 293T cells. The LS-soluble chromatin extracts were prepared for testing H3 levels and PCNA control. The total cell lysates were prepared for testing E3 ligase expression and actin control. (H) U251 cells expressing SFB-RNF8 were treated with or without 100 ng/ml EGF for 6 h. (I) U251 cells expressing His-H3 were treated with or without 100 ng/ml EGF for 6 h in the presence of 25 µM MG132. The LS-soluble chromatin extracts (H) and cell lysates for ubiquitylation assay (I) were prepared. (J–L) RNF8 was depleted in U251 cells by expressing RNF8 shRNA and reconstituted with expression of WT rRNF8, rRNF8 RING finger–deleted, or FHA-M mutants. The total cell lysates were prepared (J). These cells were also treated with or without 100 ng/ml EGF and 25 µM MG132 for 6 h (K) or with or without 100 ng/ml EGF for 24 h (L). Cell lysates for ubiquitylation assay (K) and the LS-soluble chromatin extracts (L) were prepared. (M) RNF8+/+ and RNF8−/− MEFs were treated with or without 100 ng/ml EGF for 24 h. LS-soluble chromatin extracts were prepared for H3 level and PCNA control. Total cell lysates were prepared for RNF8 protein level and actin control. The experiments shown in B and M were repeated four times. The other experiments were repeated three times.

To determine the mechanisms underlying EGF-induced histone H3 degradation, we pretreated U251 cells with cycloheximide (CHX), which blocks protein synthesis. Cycloheximide treatment did not inhibit EGF-induced histone H3 down-regulation (Fig. S1 D), suggesting that histone H3 expression is primarily regulated by altering histone H3 stability. This assumption was supported by treatment of U87/EGFR, U87/EGFRvIII (Fig. 1 E), and U251 (Fig. S1 E) cells with MG132 proteasome inhibitor, which blocked EGF-induced histone H3 down-regulation in U87/EGFR and U251 cells and increased H3 expression in U87/EGFRvIII cells. In line with these results supporting proteasome-dependent histone H3 degradation, EGF treatment induced polyubiquitylation of histone H3 immunoprecipitated from total cell lysates of U251 cells (Fig. 1 F). These results indicated that EGF treatment results in polyubiquitylation and proteasome-dependent degradation of H3 in transcriptionally active chromatin regions.

To identify the E3 ligase that ubiquitylates histone H3, we overexpressed nucleus-located E3 ligases, including RNF8 and CUL4-DDB-ROC1, that are known for ubiquitylating H2AX, H2A, H3, or H4 in response to irradiation (Wang et al., 2006; Huen et al., 2007), as well as SMAD-specific E3 ubiquitin protein ligase (Smurf)1, Smurf2, and HECTH9. Fig. 1 G shows that only RNF8 expression resulted in enhanced histone H3 degradation. Immunoblotting analyses of immunoprecipitated RNF8 with an anti–histone H3 antibody showed that EGF treatment induced an association between histone H3 and RNF8 (Fig. 1 H). RNF8 is known to contain a FHA domain and a RING finger and is involved in DNA damage–induced K63-linked polyubiquitylation of H2AX or H2A (Huen et al., 2007; Kolas et al., 2007; Mailand et al., 2007; Wang and Elledge, 2007; Peuscher and Jacobs, 2011). EGF treatment resulted in K48-linked, but not K63-linked, polyubiquitylation of histone H3 (Fig. 1 I), and depletion of RNF8 with shRNA (Fig. 1 J) blocked EGF-induced K48-linked polyubiquitylation (Fig. 1 K) and degradation of histone H3 (Fig. 1 L). Notably, the effect of RNF8 depletion on histone degradation was abrogated by reconstituted expression of WT, but not FHA domain–mutated, RNF8 (FHA-M: R42/S60/R61A) or a RING finger–deleted mutant (RNF8 ΔRING) in U251 (Fig. 1 L) and U87/EGFR cells (not depicted), indicating that the RNF8 E3 ligase activity and FHA domain play essential roles in histone H3 degradation. In line with these results, RNF8-deficient mouse fibroblasts displayed a strong resistance to EGF-induced histone H3 degradation compared with their WT counterparts (Fig. 1 M). These results indicated that RNF8 is essential for EGF-induced histone H3 ubiquitylation and degradation.

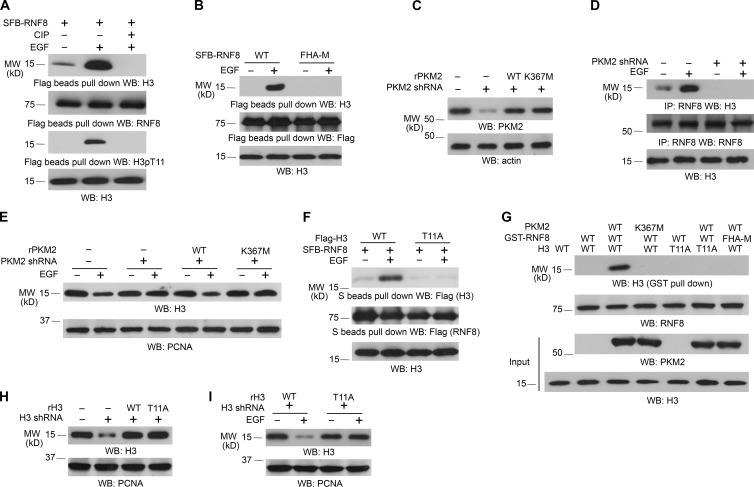

RNF8 FHA domain binds to phosphorylated histone H3 at T11

RNF8 preferentially binds to threonine (Thr, T)-phosphorylated proteins, whereas T11 phosphorylation of histone H3 plays a crucial role in EGF-promoted gene transcription (Huen et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2012b). Treatment of immunoprecipitated RNF8 and histone H3 complex from EGF-treated U251 cells with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase, which abrogated phosphorylation of histone H3 at T11, disrupted the association between histone H3 and RNF8 (Fig. 2 A), indicating that histone H3 phosphorylation is required for this protein complex formation. This finding was further supported by the fact that the RNF8 FHA-M mutant, which lost its ability to bind to Thr-phosphorylated protein (Huen et al., 2007; Mahajan et al., 2008), was unable to associate with histone H3 (Fig. 2 B).

Figure 2.

RNF8 FHA domain binds to phosphorylated histone H3 at T11. Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation (IP) analyses were performed with the indicated antibodies. WB, Western blot. (A) SFB-RNF8 immunoprecipitated from U251 cells with or without 100 ng/ml EGF treatment for 6 h was incubated with or without 10 U calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (CIP) for 1 h at 37°C, followed by washing three times with PBS. LS-soluble chromatin extracts were prepared. (B) U251 cells expressing SFB-tagged WT RNF8 or RNF8 FHA-M mutant were treated with or without 100 ng/ml EGF for 6 h. LS-soluble chromatin extracts were prepared. (C–E) U251 cells with or without expression of PKM2 shRNA were reconstituted with the expression of WT rPKM2 or rPKM2 K367M mutant (C). Cells were treated with or without 100 ng/ml EGF for 6 h. Coimmunoprecipitation between histone H3 and RNF8 was examined (D). Histone H3 expression levels of cells treated with or without 100 ng/ml EGF for 24 h were examined (E). LS-soluble chromatin extracts were prepared (D and E). (F) U251 cells expressing SFB-tagged RNF8 and Flag-tagged WT histone H3.3B or H3.3B-T11A mutant were treated with or without 100 ng/ml EGF for 6 h. LS-soluble chromatin extracts were prepared. (G) Purified WT histone H3.3B or H3.3B-T11A mutant was mixed with His-PKM2 WT or His-PKM2 K367M for an in vitro phosphorylation reaction. The mixture was then incubated with purified and immobilized WT GST-RNF8 or GST-RNF8 FHA-M mutant on glutathione agarose beads for in vitro pull-down analyses. (H and I) U251 cells with or without expression of histone H3.3 shRNA and reconstituted expression of WT histone rH3.3B and rH3.3B-T11A mutant (H) were treated with or without 100 ng/ml EGF for 24 h (I). LS-soluble chromatin extracts were prepared. All of the experiments were repeated three times.

Our previous study demonstrated that pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2), which is up-regulated by EGF stimulation, phosphorylates histone H3 at T11 and promotes EGF-induced expression of genes such as MYC and CCND1 (encoding for cyclin D1; Yang et al., 2012a,b). Expression of PKM2 shRNA, which depleted PKM2 in U251 (Fig. 2 C) and U87/EGFR (Fig. S2 A) cells, blocked the interaction between RNF8 and histone H3 (Fig. 2 D) and histone H3 degradation (Fig. 2 E and Fig. S2 B) induced by EGF stimulation; the effect of PKM2 depletion on histone H3 expression was abrogated by reconstituted expression of WT PKM2, but not its PKM2 K367M inactive mutant (Fig. 2 E and Fig. S2 B). In addition, coimmunoprecipitation analyses showed that RNF8 interacts with WT histone H3, but not with the histone T11A mutant, upon EGF treatment (Fig. 2 F). Furthermore, in vitro pull-down assay by mixing purified WT GST-RNF8 or GST-RNF8 FHA-M mutant with purified WT histone H3 or H3-T11A mutant in the presence or absence of WT PKM2 or PKM2 K367M showed that RNF8 did not bind to H3; however, inclusion of WT PKM2, but not PKM2 K367M, enabled WT RNF8, but not RNF8 FHA-M mutant, bound to WT histone H3, but not H3-T11A (Fig. 2 G). These results indicated that RNF8 binds to EGF-induced and PKM2-phosphorylated histone H3 at T11.

Histone H3 is coded by several genes in the human genome and expresses as H3.1, H3.2, and H3.3 (H3.3 having H3.3A, H3.3B, and H3.3C isoforms encoded by H3F3A, H3F3B, and H3F3C, respectively), with highly conserved sequences that differ by only a few amino acids (Marzluff et al., 2002; Hake et al., 2006). The large reduction of total H3 expression by H3.3 shRNA in both U251 (Fig. 2 H) and U87/EGFR cells (Fig. S2 C), as detected by an antibody that recognizes all H3 variants, suggested that H3.3 is the primary histone H3 isoform in both cells (Yang et al., 2012b). Reconstituted expression of RNAi-resistant WT histone rH3.3B and rH3.3B–T11A mutant in U251 (Fig. 2 H) and U87/EGFR cells (Fig. S2 C) showed that H3.3B-T11A, but not its WT counterpart, is resistant to degradation induced by EGF stimulation (Fig. 2 I and Fig. S2 D). These results indicated that PKM2-mediated phosphorylation of histone H3 at T11 is pivotal for EGF-induced and RNF8-mediated histone H3 degradation.

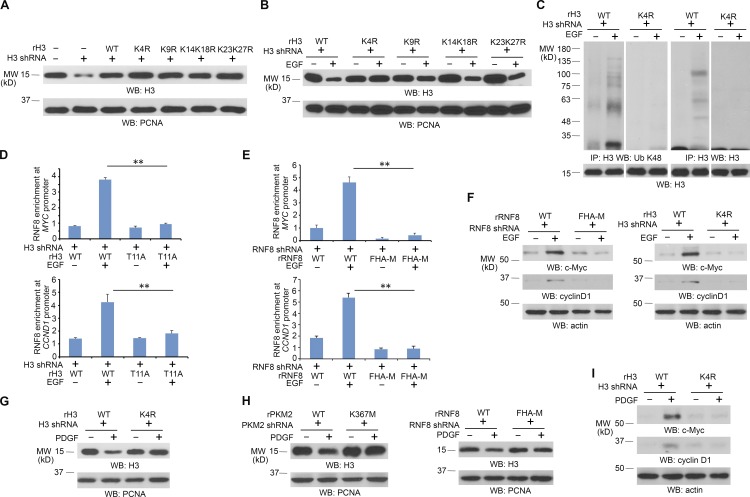

RNF8-mediated histone H3 ubiquitylation at K4 promotes MYC and CCND1 expression

To identify the EGF-induced ubiquitylation residue of histone H3, we mutated K4, K9, K14, K18, K23, and K27, which are located at the N-terminal tail of histone H3.3B, into arginine. Reconstituted expression of these mutants in U251 cells (Fig. 3 A) showed that histone H3.3B-K4R, but not the other H3.3B mutants, was resistant to EGF-induced histone H3.3 degradation (Fig. 3 B) and largely reduced ubiquitylation of H3.3 upon EGF stimulation of U251 (Fig. 3 C). Resistance of reconstituted expression of H3.3B-K4R for EGF-induced degradation was also observed in U87/EGFR cells (Fig. S3 A). In addition, we performed an in vitro ubiquitylation assay and showed that purified histone H3 is ubiquitylated by purified RNF8. In contrast, H3K4R mutant reduced RNF8-mediated histone H3 ubiquitylation, suggesting that H3K4 is ubiquitylated by RNF8 and additional lysines of H3 are also ubiquitylated in this in vitro setting (Fig. S3 B). These results strongly suggested that RNF8 ubiquitylates histone H3 at K4.

Figure 3.

RNF8-mediated histone H3 ubiquitylation at K4 promotes MYC and CCND1 expression. Immunoblotting analyses were performed with the indicated antibodies. IP, immunoprecipitation; WB, Western blot. (A and B) U251 cells expressing histone H3.3 shRNA were reconstituted with expression of WT rH3.3B or the indicated rH3.3B mutants (A). These cells were treated with or without 100 ng/ml EGF for 24 h (B). LS-soluble chromatin extracts were prepared. (C) U251 cells expressing histone H3.3 shRNA were reconstituted with expression of WT rH3.3B or rH3.3B K4R mutant. These cells were treated with or without 100 ng/ml EGF for 6 h in the presence of 25 µM MG132. Cell lysates for ubiquitylation assay were prepared. (D) Flag-RNF8 stably expressed U251 cells with histone H3.3 depletion and reconstituted expression of WT histone rH3.3B or rH3.3B-T11A were treated with or without 100 ng/ml EGF for 6 h. ChIP assays with an anti-Flag antibody and quantitative PCR analyses with primers against promoters of MYC and CCND1 were performed. (E) U251 cells with RNF8 depletion and reconstituted expression of WT rFlag-rRNF8 or rFlag-RNF8 FHA-M mutant were treated with or without 100 ng/ml EGF for 6 h. ChIP assay with an anti-Flag antibody and quantitative PCR analyses with primers against promoters of MYC and CCND1 were performed. (D and E) The data represent the means ± SD of three independent experiments. **, P < 0.001 by Student’s t test. (F) U251 cells with RNF8 depletion and reconstituted expression of WT rRNF8 or rRNF8 FHA-M mutant or with histone H3.3 depletion and reconstituted expression of WT histone rH3.3B or rH3.3B-K4R were treated with or without 100 ng/ml EGF for 24 h. Total cell lysates were prepared. (G) U251 cells with histone H3.3 depletion and reconstituted expression of WT histone rH3.3B or rH3.3B-K4R were treated with or without 100 ng/ml PDGF for 24 h. LS-soluble chromatin extracts were prepared. (H) U251 cells with PKM2 depletion and reconstituted expression of WT rPKM2 or rPKM2 K367M or with RNF8 depletion and reconstituted expression of WT rRNF8 or rRNF8 FHA-M mutant were treated with or without 100 ng/ml PDGF for 24 h. LS-soluble chromatin extracts were prepared. (I) U251 cells with histone H3.3 depletion and reconstituted expression of WT histone rH3.3B or rH3.3B-K4R were treated with or without 100 ng/ml PDGF for 24 h. Total cell lysates were prepared. All of the experiments were repeated three times.

PKM2 phosphorylates histone H3-T11 at promoter regions of MYC and CCND1 and promotes their gene transcription (Yang et al., 2012b). To determine the role of RNF8-dependent H3 ubiquitylation in MYC and CCND1 expression, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analyses. As shown in Fig. 3 D, EGF stimulation resulted in enhanced binding of RNF8 to both the MYC and CCND1 promoter regions in U251 cells with reconstituted expression of WT histone rH3.3B, but not with reconstituted expression of the rH3.3B-T11A mutant. In addition, the RNF8 FHA-M mutant, unlike its WT counterpart, failed to bind to the promoter regions of MYC and CCND1 (Fig. 3 E). Consistent with these findings, depletion of RNF8 and reconstituted expression of RNF8 FHA-M mutant and depletion of H3.3 and reconstituted expression of histone H3.3B-K4R mutant blocked EGF-induced expression of c-Myc and cyclin D1 (Fig. 3 F). Given that H3-K4 methylation at the promoter regions of MYC and CCND1 was not much altered upon EGF treatment (Fig. S3 C), these results strongly suggested that H3-K4 ubiquitylation is important for EGF-induced expression of c-Myc and cyclin D1.

Acting similarly to EGF, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) also induced degradation of WT histone H3.3B, but not H3.3B-K4R mutant, in U251 cells (Fig. 3 G). The H3 degradation was blocked by depletion of PKM2 and RNF8, which was rescued by reconstituted expression of WT rPKM2 and WT rRNF8, but not by that of the rPKM2 K367M and rRNF8 FHA-M mutants (Fig. 3 H). Furthermore, rH3.3B K4R expression blocked PDGF-induced expression of c-Myc and cyclin D1 (Fig. 3 I). These results indicated that the activation of both EGFR and PDGFR promote PKM2- and RNF8-dependent histone H3 degradation and expression of c-Myc and cyclin D1.

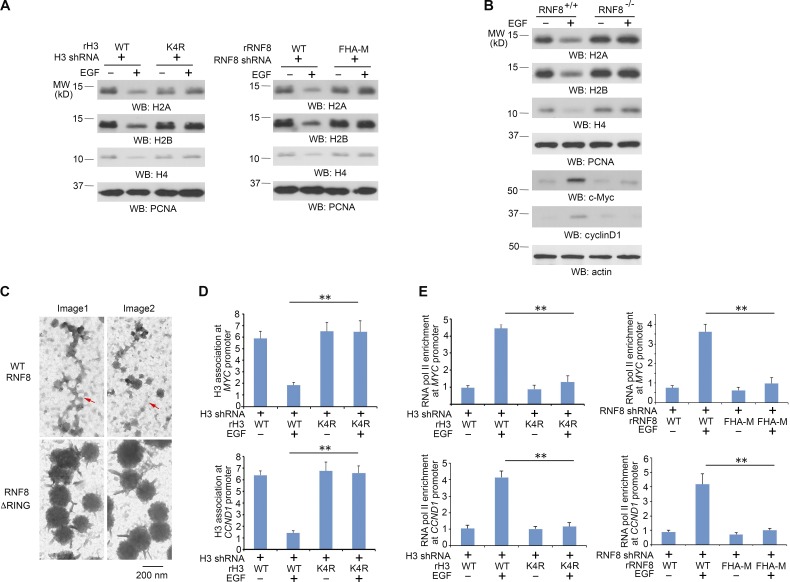

RNF8-mediated histone H3-K4 ubiquitylation promotes nucleosome disassembly

For eukaryotic gene activation, nucleosomes need to be displaced to permit transcription factors and the transcriptional machinery to bind to the DNA (Williams and Tyler, 2007; Henikoff, 2008). Intriguingly, H2A, H2B, and H4 were down-regulated upon EGF stimulation, and this down-regulation was blocked by reconstituted expression of rH3.3B-K4R mutant and rRNF8 FHA-M mutant in U251 (Fig. 4 A) and U87/EGFR (Fig. S4 A) cells. Consistently, RNF8 deficiency in mouse fibroblasts blocked EGF-induced down-regulation of H2A, H2B, and H4 and up-regulation of c-Myc and cyclin D1 (Fig. 4 B), whereas RNF8 overexpression reduced basal expression levels of H2A, H2B, and H4, which were further down-regulated by EGF treatment (Fig. S4 B). In addition, MG132 proteasome inhibitor treatment increased H2A, H2B, and H4 protein levels in U87/EGFRvIII cells (Fig. S4 C), indicating proteasomal degradation of these proteins.

Figure 4.

RNF8-mediated histone H3-K4 ubiquitylation promotes nucleosome disassembly. Immunoblotting analyses were performed with the indicated antibodies. WB, Western blot. (A) U251 cells with histone H3.3 depletion and reconstituted expression of WT histone rH3.3B or rH3.3B-K4R or with RNF8 depletion and reconstituted expression of WT rRNF8 or rRNF8 FHA-M mutant were treated with or without 100 ng/ml EGF for 24 h. LS-soluble chromatin extracts were prepared. (B) RNF8+/+ and RNF8−/− MEFs were treated with or without 100 ng/ml EGF for 24 h. LS-soluble chromatin extracts were prepared for detection of H2A, H2B, H4, and PCNA control. Total cell lysates were used to determine the expression levels of c-Myc, cyclinD1, and actin control. (C) U251 cells with RNF8 depletion and reconstituted expression of WT rFlag-RNF8 or rFlag-RNF8 ΔRING mutant were treated with 100 ng/ml EGF for 8 h, followed by formaldehyde fixation, micrococcal nuclease digestion, ChIP with an anti-Flag antibody, and electron microscopy analyses. The red arrows point to the chromatin regions with disassembled nucleosomes. Two samples were prepared, and ∼60 pictures were taken for each group. Two representative pictures are shown for WT rFlag-RNF8 or rFlag-RNF8 ΔRING mutant accordingly. (D) U251 cells with histone H3.3 depletion and reconstituted expression of WT histone rH3.3B or rH3.3B-K4R mutant were treated with or without 100 ng/ml EGF for 8 h. ChIP assay with an anti-H3 antibody and quantitative PCR analyses with the primers against promoters of MYC and CCND1 were performed. (E) U251 cells with histone H3.3 depletion and reconstituted expression of WT histone rH3.3B or rH3.3B-K4R mutant or with RNF8 depletion and reconstituted expression of WT rRNF8 or rRNF8 FHA-M mutant were treated with or without 100 ng/ml EGF for 8 h. ChIP assay with an anti–RNA Pol II antibody and quantitative PCR analyses with the primers against promoters of MYC and CCND1 were performed. (D and E) The data represent the means ± SD of three independent experiments. **, P < 0.001 by Student’s t test. The experiments shown in A and B were repeated three times.

To identify if RNF8-dependent histone H3 degradation induced nucleosome disassembly in transcriptionally active chromatin regions, we performed electron microscopy analyses of immunoprecipitated Flag-tagged WT RNF8- or RNF8 ΔRING–associated chromatin fractions from EGF-stimulated cells. Fig. 4 C shows that the sizes of the WT RNF8-associated nucleosomes, which apparently underwent disassembly, were much smaller than those associated with the RNF8 ΔRING mutant. In addition, many more areas of chromatin were disassociated with histones in WT RNF8 immunoprecipitates than in the RNF8 ΔRING mutant immunoprecipitates. In line with this finding, ChIP analyses using an anti–H3 antibody and primers of CCND1 and MYC promoter for PCRs showed that EGF treatment reduced the association of H3 in the promoter regions of U251 cells with histone H3.3 depletion and reconstituted expression of WT histone rH3.3B, but not in cells with reconstituted expression of rH3.3B-K4R (Fig. 4 D). Furthermore, ChIP analyses demonstrated that EGF stimulation resulted in the binding of RNA polymerase II to the promoter regions of MYC and CCND1, which was blocked by reconstituted expression of the rH3.3B-K4R mutant (Fig. 4 E, left), the rRNF8 FHA-M mutant (Fig. 4 E, right), and the RNF8 ΔRING mutant (not depicted). These results indicate that RNF8-mediated histone H3 ubiquitylation and subsequent disassembly of nucleosomes promotes the assembly of gene transcription machinery on the promoter regions of MYC and CCND1.

RNF8-mediated histone H3 ubiquitylation promotes tumor cell glycolysis and tumorigenesis

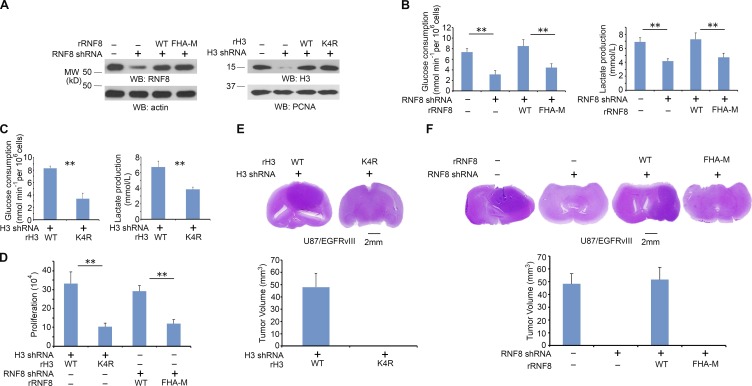

c-Myc–regulated glycolytic gene expression and increased cyclin D1 expression are essential for the EGF-promoted Warburg effect and cell cycle progression, respectively (Yang et al., 2012b,c). To investigate the role of histone H3-K4 ubiquitylation in EGFR-regulated tumor cell glycolysis, we depleted RNF8 or histone H3.3 in U87/EGFRvIII cells and reconstituted the cells with WT rRNF8, rRNF8 FHA-M, WT histone rH3.3B, or histone rH3.3B-K4R mutant (Fig. 5 A). U87/EGFRvIII cells had higher levels glucose consumption and lactate production than U87 cells (Fig. S5 A), and this increase was inhibited by RNF8 depletion. In addition, RNF8 depletion–reduced glucose consumption and lactate production were rescued by reconstituted expression of WT rRNF8, but not that of the rRNF8 FHA-M mutant (Fig. 5 B). Furthermore, U87/EGFRvIII cells expressing RNF8 shRNA and histone H3.3 shRNA had levels of histone H3 expression, glucose consumption, and lactate production similar to those of parental U87/EGFRvIII cells possessing intact RNF8-depdendent histone H3 degradation (Fig. S5 B). However, reconstituted expression of RNAi-resistant histone H3 suppressed glucose consumption and lactate production, and this suppression was rescued by reconstituted expression of WT rRNF8, but not that of the rRNF8 FHA-M mutant. These results suggest that RNF8 regulates glycolysis through regulation of histone H3 stability. In line with these findings, histone rH3.3B-K4R expression, compared with expression of its WT counterpart, largely reduced glucose consumption and lactate production (Fig. 5 C). In addition, reconstituted expression of rRNF8 FHA-M and rH3.3B-K4R mutants inhibited tumor cell proliferation (Fig. 5 D).

Figure 5.

RNF8-mediated histone H3 ubiquitylation promotes the glycolysis and tumorigenesis. (A) RNF8 and histone H3.3 in U87/EGFRvIII cells were depleted with expression of their shRNA and reconstituted with expression of WT rRNF8, rRNF8 FHA-M, WT histone rH3.3B, or histone rH3.3B-K4R. Total cell lysates were prepared for expression levels of RNF8 and actin control. LS-soluble chromatin extracts were prepared for detection of H3 and PCNA control. Immunoblotting analyses were performed with the indicated antibodies. Experiments were repeated three times. WB, Western blot. (B) U87/EGFRvIII cells with RNF8 depletion were reconstituted with or without expression of WT rRNF8 or rRNF8 FHA-M. Media were collected for analysis of glucose consumption (left) or lactate production (right), which was normalized by cell numbers (per 106). (C) U87/EGFRvIII cells with histone H3.3 depletion were reconstituted with expression of WT histone rH3.3B or rH3.3B-K4R. Media were collected for analysis of glucose consumption (left) or lactate production (right), which was normalized by cell numbers (per 106). (D) A total number of 3 × 104 U87/EGFRvIII cells with histone H3.3 depletion and reconstituted expression of WT histone rH3.3B or rH3.3B-K4R or with RNF8 depletion and reconstituted expression of WT rRNF8 or rRNF8 FHA-M were plated and counted 7 d after seeding in DMEM with 0.5% bovine calf serum. (B–D) Data represent the means ± SD of three independent experiments. **, P < 0.001 by Student’s t test. (E and F) 5 × 105 U87/EGFRvIII cells with H3.3 depletion and reconstituted expression of WT histone rH3.3B or rH3.3B-K4R (E) or RNF8 depletion and reconstituted expression of WT rRNF8 or rRNF8 FHA-M (F) were intracranially injected into athymic nude mice (n = 7 per group). After 2 wk, the mice were sacrificed and tumor growth was examined. H&E-stained coronal brain sections showed representative tumor xenografts (top). Tumor volumes were calculated (bottom). Data represent the means ± SD of seven mice in each group.

To investigate the role of RNF8-mediated histone H3 ubiquitylation in brain tumorigenesis, we intracranially injected U87/EGFRvIII-H3.3 shRNA cells with reconstituted expression of WT histone rH3.3B, histone rH3.3B K4R, U87/EGFRvIII–RNF8 shRNA cells, or U87/EGFRvIII–RNF8 shRNA cells with reconstituted expression of WT rRNF8 or rRNF8 FHA-M mutant into athymic nude mice. Reconstituted expression of histone H3.3B K4R, but not reconstituted expression of WT histone rH3.3B, abrogated the growth of brain tumors (Fig. 5 E). In addition, depletion of RNF8 inhibited tumorigenesis, and this effect was rescued by reconstituted expression of WT rRNF8, but not that of rRNF8 FHA-M mutant (Fig. 5 F). Similar effects of RNF8-dependent histone H3 degradation on tumorigenesis were also detected using human primary GSC11 GBM cells (not depicted). The consistency of the effects of mutant RNF8 FHA-M, histone H3-K4R, and H3-T11A expression on tumorigenesis (Yang et al., 2012b) strongly suggests that RNF8-dependent histone H3 ubiquitylation occurs during tumorigenesis in mice and highlights the significance of this regulation in brain tumor development.

Discussion

Eukaryotic histones undergo posttranslational modifications for regulation of different biological processes (Chi et al., 2010). However, the effect of growth factor receptor activation on the stability of chromatin-bound histones and on subsequent gene transcription is unknown. In this study, we demonstrate that activation of EGFR and PDGFR results in RNF8-dependent polyubiquitylation and degradation of histone H3, which requires primed PKM2-dependent histone H3 phosphorylation at T11 and binding of RNF8 to phosphorylated histone H3-T11 through its FHA domain. Importantly, RNF8-mediated H3-K4 polyubiquitylation promotes the dissociation of histones from transcriptionally active chromatin regions, degradation of free histone protein, and binding of RNA polymerase II to the loosened chromatin for gene transcription of MYC and CCND1, which promotes tumor cell glycolysis and proliferation and tumorigenesis (Fig. 6). These findings elucidate previously unrevealed mechanisms of RNF8-mediated histone degradation and nucleosome disassembly, providing instrumental insight into the growth factor–induced regulation of chromosome structure and gene expression, which is essential for growth factor receptor activation–promoted tumorigenesis.

Figure 6.

RNF8/UbcH8-mediated histone H3 polyubiquitylation and degradation promotes gene expression. EGFR activation results in PKM2 phosphorylating H3 at T11 and subsequent binding of RNF8 FHA domain to phosphorylated histone H3. RNF8-mediated H3-K4 polyubiquitylation promotes the dissociation of histone from chromatin, degradation of histones, and binding of RNA polymerase (Pol) II for gene transcription of MYC and CCND1, which promotes the glycolysis, cell proliferation, and tumorigenesis.

Of the four core histones, H2A and H2B have long been known to be modified by ubiquitylation in the regulation of cellular processes (Osley, 2004; Weake and Workman, 2008). In addition, H3 was reported to be polyubiquitylated without identified ubiquitylation residues (Zhang, 2003). H3 is polyubiquitylated, with an unknown physiological consequence, in elongating rat spermatids, and this polyubiquitylation is mediated by a testis-specific Ubc4 isoform, Ubc4-testis, and a HECT domain–containing protein, LASU1 (Chen et al., 1998; Liu et al., 2005). Non–chromatin-bound histone H3 in S. cerevisiae is subject to ubiquitylation-dependent proteolysis mediated by RAD53-dependent histone H3-Y99 phosphorylation (Singh et al., 2009). Nevertheless, whether H3 is monoubiquitylated at multiple lysines or polyubiquitylated of one or more lysines in H3 was not clear (Singh et al., 2009). In response to irradiation, CUL4-DDB-ROC1 E3 ligase complex mediated ubiquitylation of histone H3 and H4 and RNF8-Ubc13 mediated K63-linked polyubiquitylation of histone H1, which weakens the interaction between histones and DNA and facilitates the recruitment of repair proteins to damaged DNA (Wang et al., 2006; Thorslund et al., 2015). We showed here that CUL4-DDB-ROC1 expression did not affect EGFR activation–induced histone H3 degradation. In contrast, RNF8 depletion in tumor cells or deficiency in MEFs inhibited EGF-induced and K-48-linked histone H3 polyubiquitylation and degradation. Expression of histone H3.3B-K4R, which is resistant to polyubiquitylation, blocked the disassociation of histones from nucleosomes, which is required for gene expression. These results suggest that signaling context–dependent coupling of different E3–E2 complexes to histone is instrumental for K-48– or K-63–linked polyubiquitylation of histone and subsequent regulation of histone functions or stability.

EGFR overexpression or mutation occurs in up to 60% of human GBM (Wykosky et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2011). Expression of EGFRvIII in U87 cells, which elicits rapid brain tumor growth (Yang et al., 2011), results in a decrease of histone expression, suggesting that activation of receptor tyrosine kinase–driven accelerated cell growth and proliferation requires disassembly of nucleosomes and a rapid turnover of histones so that the gene transcriptional machinery is maintained at a highly active state. Given the broad effect of PKM2 on gene expression by acting as a coactivator of transcriptional factors or regulators, including β-catenin, HIF1α, and STAT3 (Yang and Lu, 2015), these findings highlight the instrumental role of PKM2/RNF8–mediated histone H3 polyubiquitylation in the regulation of histone H3 stability and chromatin modification, which is instrumental for epigenetic regulation of gene expression and tumorigenesis.

Materials and methods

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies recognizing phospho–histone H3 T11, H2B, and c-Myc were obtained from Signalway Antibody. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies recognizing all histone H3 variants, histone H2A, H3K9ac, H3K9me3, H3K79me2, RNA polymerase II, and goat antibodies for RNF8 and H3 were obtained from Abcam. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies for H3K36me3, HP1 α are from Cell Signaling Technology. Mouse monoclonal antibodies for GST and rabbit polyclonal antibodies for cyclin D1, histone H4 and RNF8 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Mouse monoclonal antibody for PCNA was from BD. Rabbit monoclonal antibodies recognizing ubiquitin, ubiquitin Lys-48, and Lys-63 were from EMD Millipore. EGF, cycloheximide, MG132, a glucose assay kit, GST-binding resin, rabbit polyclonal antibody for Flag and mouse monoclonal antibody for Flag, His, and tubulin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Hygromycin, puromycin, DNase-free RNase A, and propidium iodide were purchased from EMD Biosciences. HyFect transfection reagents were from Denville Scientific. GelCode Blue Stain Reagent was obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Cocktail protease inhibitor was from Roche. The lactate assay kit was from Eton Bioscience, Inc. Anti-Flag affinity beads were from BioLegend. S-protein agarose beads were from GenScript.

Cells and cell culture conditions

U251, U87, U87/EGFR, and U87/EGFRvIII GBM cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone). MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells, A431 human epidermoid carcinoma cells, and 293T cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% bovine calf serum (HyClone). Human primary GSC11 GBM cells were maintained in DMEM/F-12 50/50 supplemented with B27, 10 ng/ml EGF, and 10 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor. Cell cultures were made quiescent by growing them to confluence, and the medium was replaced with fresh medium containing 0.5% serum for 1 d. EGF at a final concentration of 100 ng/ml was used for cell stimulation.

Transfection

Cells were plated at a density of 4 × 105/60-mm dish 18 h before transfection. Transfection was performed as previously described (Xia et al., 2007).

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting analysis

Extraction of proteins with a modified buffer from cultured cells was followed by immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting with corresponding antibodies as described previously (Lu et al., 1998). To detect H3 ubiquitylation in vivo, we prepared denatured cell extracts before immunoprecipitation by resuspending cell pellets in 100 µl denaturing buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1% SDS, and 1 mM DTT). Samples were boiled for 10 min, and immunoprecipitations were performed after adding 900 µl TNN buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 0.25 M NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, 0.5% NP-40, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM phenylmethyl sulphoxide, and 1X protease inhibitor cocktail).

Cell proliferation assay

A total of 3 × 104 cells were plated and counted 7 d after seeding in DMEM with 0.5% bovine calf serum. Data represent the mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

DNA constructs and mutagenesis

PCR-amplified human histone H3.3B was cloned into lentiviral vector pCDH (between NheI and NotI), pCold vector (between XhoI and HindIII), and pcDNA3.1/Flag vector (between BamHI and NotI). Histone H3 K4R, K9R, T11A, K14R, K18R, K23R, and K27R and the RNF8 FHA domain R42S60R61A mutant were generated by using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies). PCR-amplified human WT and mutant RNF8 were cloned into pCDH between NheI and NotI. SFB-RNF8, Flag-RNF8, RING depletion mutant, and GST-RNF8 were gifts from J. Chen’s laboratory (MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX). pcDNA3.1/PKM2 WT and K367M, pcold /PKM2 WT, and K367M have been described previously (Yang et al., 2012a,b).

The pGIPZ control was generated with control oligonucleotide 5′-GCTTCTAACACCGGAGGTCTT-3′. pGIPZ RNF8 shRNA was generated with 5′-TAAGGAGAATGCGGAGTAT-3′. pGIPZ histone H3.3B shRNA has been described previously (Yang et al., 2012b).

Purification of recombinant proteins

The WT and mutant GST-RNF8, GST-RNF8 FHA-M, WT and mutant His-H3, K4R, T11A, WT and mutant His-PKM2, and K367M were expressed in bacteria and purified as described previously (Xia et al., 2007).

S-protein, His, and GST pull-down assays

S-protein agarose, Ni-NTA His-binding resin or GST-binding resin were incubated with cell lysate or purified protein for 12 h. The beads were washed with the lysis buffer for three times.

In vitro phosphorylation assays

The bacterially purified recombinant PKM2 (200 ng) were incubated with histone H3 (100 ng) in kinase buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 50 mM MgCl2, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM DTT, 5% glycerol, 0.5 mM PEP, and 0.05 mM FBP) at 25°C for 1 h. The reactions were terminated by the addition of SDS-PAGE loading buffer and heated to 100°C. The reaction mixtures were then subjected to SDS-PAGE.

In vitro ubiquitylation assays

Reactions were performed as described previously (Lu et al., 2002). Approximately 3 µg GST-RNF8 and WT or mutant His-H3 were incubated with 50–500 nM E1, 0.5–5 µM His-E2, 10 µM GST-Ub, and 2 mM ATP in reaction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 2.5 mM MgCl2, and 0.5 mM DTT) for 90 min at room temperature.

Chromatin fractionation

Cells were first lysed with buffer A (50 mM Hepes, pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.34 M sucrose, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, protease inhibitors, and 0.1% Triton X-100) on ice for 15 min. After centrifugation at 6,600 g for 10 min, pellets, including the nucleus, were washed in buffer A and further lysed with LS lysis buffer (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, protease inhibitors) on ice for 15 min. The soluble chromatin fraction was collected after centrifugation at 12,000 g for 10 min. Pellets containing the LS-insoluble chromatin fractions were then sonicated in the lysis buffer for Western blot analysis.

Uranyl acetate–negative staining for electron microscopy

RNF8 was depleted in U251 cells by expressing RNF8 shRNA and was reconstituted with expression of Flag-tagged WT rRNF8 or rRNF8 RING finger–deleted mutant. After 100 ng/ml EGF treatment for 8 h, cells were fixed with formaldehyde and collected for micrococcal nuclease digestion. The cross-linked chromatin fractions were then incubated with an anti-Flag antibody and ChIP-grade protein G beads. The immunoprecipitated chromatin was washed and eluted with Flag peptides. The eluted samples were placed on 400-mesh carbon-coated, formvar-coated copper grids treated with poly-l-lysine for 30 min and then negatively stained with EMD Millipore–filtered aqueous 1% uranyl acetate for 1 min. The stain was blotted dry from the grids with filter paper, and the samples were allowed to dry. The samples were then examined using a JEM 1010 transmission electron microscope (JEOL) at an accelerating voltage of 80 kV. Digital images were obtained using the AMT Imaging System (Advanced Microscopy Techniques Corp.).

Measurements of glucose consumption and lactate production

Cells were seeded in culture dishes, and the medium was changed after 6 h with nonserum DMEM. Cells were incubated for 12–16 h, and the culture medium was then collected for measurement of glucose and lactate concentrations. Glucose levels were determined using a glucose (GO) assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich). Glucose consumption was the difference in glucose concentration between the collected culture medium and DMEM. Lactate levels were determined using a lactate assay kit (Eton Bioscience, Inc.).

ChIP assay

ChIP was performed by using SimpleChIP Enzymatic Chromatin IP kit (Cell Signaling Technology). Chromatin prepared from cells (in a 10-cm dish) was used to determine total DNA input and for overnight incubation with the specific antibodies or with normal rabbit or mouse immunoglobulin G. For ChIP assay with anti-Flag, anti-H3, and anti-RNA pol II, the CCND1 promoter–specific primers used in PCR were 5′-TGCCGGGCTTTGATCTTT-3′ (forward) and 5′-CACAGGAGCTGGTGTTCCAT-3′ (reverse). MYC promoter–specific primers were 5′-GGGTTCCCAAAGCAGAGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCTGGAATTACTACAGCGAGTT-3′ (reverse).

Intracranial injection

We intracranially injected 5 × 105 GBM cells (in 5 µl DMEM per mouse) with endogenous histone H3.3 depletion and reconstituted expression of histone WT rH3.3B or rH3.3B-K4R or with endogenous RNF8 depletion and reconstituted expression of WT rRNF8 or rRNF8 FHA-M mutant into 4-wk-old female athymic nude mice. The intracranial injections were performed as described in a previous publication (Gomez-Manzano et al., 2006). Seven mice per group in each experiment were included. Mice injected with U87/EGFRvIII or GSC11 GBM cells were sacrificed 14 or 30 d after glioma cell injection, respectively. The tumor sizes and volumes were measured before and after treatment as described previously (Yang et al., 2011). The data are presented as the means ± SD in seven mice.

The brain of each mouse was harvested, fixed in 4% formaldehyde, and embedded in paraffin. The specimens were stained with Mayer’s hematoxylin and subsequently with eosin (Biogenex Laboratories). Afterward, the slides were mounted by using a Universal Mount (Research Genetics). The use of animals was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Quantification and statistical analysis

All data represent the mean ± SD of at least three independent experiments. Sample number (n) indicates the number of independent biological samples in each experiment. Sample numbers and experimental repeats are indicated in figure legends. A statistical analysis was conducted with the two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test unless specifically indicated. Differences in means were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05 (**, P < 0.001; *, P < 0.01; N.S., not significant).

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows that EGFR activation induces histone H3 degradation in U251, MDA-MB-231, and A431 cells and that pretreatment of U251 cells with AG1478 and MG132, but not cycloheximide, inhibits EGF-induced H3 degradation. Fig. S2 shows that PKM2 and H3T11 are important for EGF-induced H3 degradation in U87/EGFR cells. Fig. S3 shows that RNF8-mediated histone H3 ubiquitylation at K4 is required for EGF-induced histone H3 ubiquitylation and degradation. Fig. S4 shows that RNF8-mediated histone H3-K4 ubiquitylation promotes nucleosome disassembly in U251, U87/EGFR, and U87/EGFRvIII cells. Fig. S5 shows that RNF8-mediated histone H3 ubiquitylation promotes the glycolysis in U87/EGFRvIII cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Junjie Chen (MD Anderson Cancer Center) for RNF8 plasmids; Hui-Kuan Lin (MD Anderson Cancer Center) for Flag-Smurf1, Flag-Smurf2, and HA-HECTH9 plasmids; Shuo Dong (Baylor College of Medicine) for MLL plasmid; and Jianping Jin (UT Medical School) for Myc-Cul4A plasmid.

This work was supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke grant 1R01 NS089754 (to Z. Lu), National Cancer Institute grants 2R01 CA109035, 1R01 CA169603, and 1R01 CA204996 (to Z. Lu), The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Research Grant (to Y. Xia), National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute MD Anderson Support Grant P30CA016672, James S. McDonnell Foundation 21st Century Science Initiative in Brain Cancer Research Award 220020318 (to Z. Lu), and National Institutes of Health Brain Cancer Specialized Program of Research Excellence grant 2P50 CA127001. Z. Lu is a Ruby E. Rutherford Distinguished Professor.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used:

- ChIP

- chromatin immunoprecipitation

- EGF

- epidermal growth factor

- FHA

- forkhead associated

- GBM

- glioblastoma

- LS

- low salt

- PDGF

- platelet-derived growth factor

References

- Barski A., Cuddapah S., Cui K., Roh T.Y., Schones D.E., Wang Z., Wei G., Chepelev I., and Zhao K.. 2007. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell. 129:823–837. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassermann F., Eichner R., and Pagano M.. 2014. The ubiquitin proteasome system - Implications for cell cycle control and the targeted treatment of cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1843:150–162. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.02.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrends C., and Harper J.W.. 2011. Constructing and decoding unconventional ubiquitin chains. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18:520–528. 10.1038/nsmb.2066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.Y., Sun J.M., Zhang Y., Davie J.R., and Meistrich M.L.. 1998. Ubiquitination of histone H3 in elongating spermatids of rat testes. J. Biol. Chem. 273:13165–13169. 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi P., Allis C.D., and Wang G.G.. 2010. Covalent histone modifications–Miswritten, misinterpreted and mis-erased in human cancers. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 10:457–469. 10.1038/nrc2876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clague M.J., and Urbé S.. 2010. Ubiquitin: Same molecule, different degradation pathways. Cell. 143:682–685. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Manzano C., Alonso M.M., Yung W.K., McCormick F., Curiel D.T., Lang F.F., Jiang H., Bekele B.N., Zhou X., Alemany R., and Fueyo J.. 2006. Delta-24 increases the expression and activity of topoisomerase I and enhances the antiglioma effect of irinotecan. Clin. Cancer Res. 12:556–562. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hake S.B., Garcia B.A., Duncan E.M., Kauer M., Dellaire G., Shabanowitz J., Bazett-Jones D.P., Allis C.D., and Hunt D.F.. 2006. Expression patterns and post-translational modifications associated with mammalian histone H3 variants. J. Biol. Chem. 281:559–568. 10.1074/jbc.M509266200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henikoff S. 2008. Nucleosome destabilization in the epigenetic regulation of gene expression. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9:15–26. 10.1038/nrg2206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henikoff S., Henikoff J.G., Sakai A., Loeb G.B., and Ahmad K.. 2009. Genome-wide profiling of salt fractions maps physical properties of chromatin. Genome Res. 19:460–469. 10.1101/gr.087619.108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huen M.S., Grant R., Manke I., Minn K., Yu X., Yaffe M.B., and Chen J.. 2007. RNF8 transduces the DNA-damage signal via histone ubiquitylation and checkpoint protein assembly. Cell. 131:901–914. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolas N.K., Chapman J.R., Nakada S., Ylanko J., Chahwan R., Sweeney F.D., Panier S., Mendez M., Wildenhain J., Thomson T.M., et al. . 2007. Orchestration of the DNA-damage response by the RNF8 ubiquitin ligase. Science. 318:1637–1640. 10.1126/science.1150034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuan C.T., Wikstrand C.J., and Bigner D.D.. 2001. EGF mutant receptor vIII as a molecular target in cancer therapy. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 8:83–96. 10.1677/erc.0.0080083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latham J.A., and Dent S.Y.. 2007. Cross-regulation of histone modifications. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14:1017–1024. 10.1038/nsmb1307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Oughtred R., and Wing S.S.. 2005. Characterization of E3Histone, a novel testis ubiquitin protein ligase which ubiquitinates histones. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:2819–2831. 10.1128/MCB.25.7.2819-2831.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z., and Hunter T.. 2009. Degradation of activated protein kinases by ubiquitination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78:435–475. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.013008.092711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z., Liu D., Hornia A., Devonish W., Pagano M., and Foster D.A.. 1998. Activation of protein kinase C triggers its ubiquitination and degradation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:839–845. 10.1128/MCB.18.2.839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z., Xu S., Joazeiro C., Cobb M.H., and Hunter T.. 2002. The PHD domain of MEKK1 acts as an E3 ubiquitin ligase and mediates ubiquitination and degradation of ERK1/2. Mol. Cell. 9:945–956. 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00519-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luger K., Mäder A.W., Richmond R.K., Sargent D.F., and Richmond T.J.. 1997. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature. 389:251–260. 10.1038/38444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan A., Yuan C., Lee H., Chen E.S., Wu P.Y., and Tsai M.D.. 2008. Structure and function of the phosphothreonine-specific FHA domain. Sci. Signal. 1:re12 10.1126/scisignal.151re12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailand N., Bekker-Jensen S., Faustrup H., Melander F., Bartek J., Lukas C., and Lukas J.. 2007. RNF8 ubiquitylates histones at DNA double-strand breaks and promotes assembly of repair proteins. Cell. 131:887–900. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maison C., and Almouzni G.. 2004. HP1 and the dynamics of heterochromatin maintenance. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5:296–305. 10.1038/nrm1355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzluff W.F., Gongidi P., Woods K.R., Jin J., and Maltais L.J.. 2002. The human and mouse replication-dependent histone genes. Genomics. 80:487–498. 10.1006/geno.2002.6850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osley M.A. 2004. H2B ubiquitylation: The end is in sight. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1677:74–78. 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2003.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osley M.A., Fleming A.B., and Kao C.F.. 2006. Histone ubiquitylation and the regulation of transcription. Results Probl. Cell Differ. 41:47–75. 10.1007/400_006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peuscher M.H., and Jacobs J.J.. 2011. DNA-damage response and repair activities at uncapped telomeres depend on RNF8. Nat. Cell Biol. 13:1139–1145. 10.1038/ncb2326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha E., Davie J.R., van Holde K.E., and Weintraub H.. 1984. Differential salt fractionation of active and inactive genomic domains in chicken erythrocyte. J. Biol. Chem. 259:8558–8563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R.K., Kabbaj M.H., Paik J., and Gunjan A.. 2009. Histone levels are regulated by phosphorylation and ubiquitylation-dependent proteolysis. Nat. Cell Biol. 11:925–933. 10.1038/ncb1903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger D.J., Lefterova M.I., Ying L., Stonestrom A.J., Schupp M., Zhuo D., Vakoc A.L., Kim J.E., Chen J., Lazar M.A., et al. . 2008. DOT1L/KMT4 recruitment and H3K79 methylation are ubiquitously coupled with gene transcription in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28:2825–2839. 10.1128/MCB.02076-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strahl B.D., and Allis C.D.. 2000. The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature. 403:41–45. 10.1038/47412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z.W., and Allis C.D.. 2002. Ubiquitination of histone H2B regulates H3 methylation and gene silencing in yeast. Nature. 418:104–108. 10.1038/nature00883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J.M., Chen H.Y., Espino P.S., and Davie J.R.. 2007. Phosphorylated serine 28 of histone H3 is associated with destabilized nucleosomes in transcribed chromatin. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:6640–6647. 10.1093/nar/gkm737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorslund T., Ripplinger A., Hoffmann S., Wild T., Uckelmann M., Villumsen B., Narita T., Sixma T.K., Choudhary C., Bekker-Jensen S., and Mailand N.. 2015. Histone H1 couples initiation and amplification of ubiquitin signalling after DNA damage. Nature. 527:389–393. 10.1038/nature15401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner E.J., and Carpenter P.B.. 2012. Understanding the language of Lys36 methylation at histone H3. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13:115–126. 10.1038/nrm3274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., and Elledge S.J.. 2007. Ubc13/Rnf8 ubiquitin ligases control foci formation of the Rap80/Abraxas/Brca1/Brcc36 complex in response to DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:20759–20763. 10.1073/pnas.0710061104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Zhai L., Xu J., Joo H.Y., Jackson S., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Xiong Y., and Zhang Y.. 2006. Histone H3 and H4 ubiquitylation by the CUL4-DDB-ROC1 ubiquitin ligase facilitates cellular response to DNA damage. Mol. Cell. 22:383–394. 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weake V.M., and Workman J.L.. 2008. Histone ubiquitination: triggering gene activity. Mol. Cell. 29:653–663. 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams S.K., and Tyler J.K.. 2007. Transcriptional regulation by chromatin disassembly and reassembly. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 17:88–93. 10.1016/j.gde.2007.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wykosky J., Fenton T., Furnari F., and Cavenee W.K.. 2011. Therapeutic targeting of epidermal growth factor receptor in human cancer: successes and limitations. Chin. J. Cancer. 30:5–12. 10.5732/cjc.010.10542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y., Wang J., Liu T.J., Yung W.K., Hunter T., and Lu Z.. 2007. c-Jun downregulation by HDAC3-dependent transcriptional repression promotes osmotic stress-induced cell apoptosis. Mol. Cell. 25:219–232. 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W., and Lu Z.. 2015. Pyruvate kinase M2 at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 128:1655–1660. 10.1242/jcs.166629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W., Xia Y., Ji H., Zheng Y., Liang J., Huang W., Gao X., Aldape K., and Lu Z.. 2011. Nuclear PKM2 regulates β-catenin transactivation upon EGFR activation. Nature. 480:118–122. 10.1038/nature10598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W., Xia Y., Cao Y., Zheng Y., Bu W., Zhang L., You M.J., Koh M.Y., Cote G., Aldape K., et al. . 2012a EGFR-induced and PKCε monoubiquitylation-dependent NF-κB activation upregulates PKM2 expression and promotes tumorigenesis. Mol. Cell. 48:771–784. 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W., Xia Y., Hawke D., Li X., Liang J., Xing D., Aldape K., Hunter T., Alfred Yung W.K., and Lu Z.. 2012b PKM2 phosphorylates histone H3 and promotes gene transcription and tumorigenesis. Cell. 150:685–696. (published erratum appears in Cell 2014. 158:1210) 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W., Zheng Y., Xia Y., Ji H., Chen X., Guo F., Lyssiotis C.A., Aldape K., Cantley L.C., and Lu Z.. 2012c ERK1/2-dependent phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of PKM2 promotes the Warburg effect. Nat. Cell Biol. 14:1295–1304. 10.1038/ncb2629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. 2003. Transcriptional regulation by histone ubiquitination and deubiquitination. Genes Dev. 17:2733–2740. 10.1101/gad.1156403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.