Changes in nutrient availability trigger massive rearrangements of the yeast plasma membrane proteome. This work shows that the arrestin-related protein Csr2/Art8 is regulated by glucose signaling at multiple levels, allowing control of hexose transporter ubiquitylation and endocytosis upon glucose depletion.

Abstract

Nutrient availability controls the landscape of nutrient transporters present at the plasma membrane, notably by regulating their ubiquitylation and subsequent endocytosis. In yeast, this involves the Nedd4 ubiquitin ligase Rsp5 and arrestin-related trafficking adaptors (ARTs). ARTs are targeted by signaling pathways and warrant that cargo ubiquitylation and endocytosis appropriately respond to nutritional inputs. Here, we show that glucose deprivation regulates the ART protein Csr2/Art8 at multiple levels to trigger high-affinity glucose transporter endocytosis. Csr2 is transcriptionally induced in these conditions through the AMPK orthologue Snf1 and downstream transcriptional repressors. Upon synthesis, Csr2 becomes activated by ubiquitylation. In contrast, glucose replenishment induces CSR2 transcriptional shutdown and switches Csr2 to an inactive, deubiquitylated form. This glucose-induced deubiquitylation of Csr2 correlates with its phospho-dependent association with 14-3-3 proteins and involves protein kinase A. Thus, two glucose signaling pathways converge onto Csr2 to regulate hexose transporter endocytosis by glucose availability. These data illustrate novel mechanisms by which nutrients modulate ART activity and endocytosis.

Introduction

Glucose is an essential nutrient that sustains cell growth and energy production in most living cells. Glucose uptake occurs by facilitated diffusion through a family of plasma membrane–localized transporters and is a highly regulated process. For example, insulin stimulates glucose storage in adipocytes through the increased targeting of the glucose transporter Glut4 to the plasma membrane (Cushman and Wardzala, 1980; Karnieli et al., 1981; Martin et al., 2000). Glut4 endocytosis is further repressed by insulin in adipocytes (Jhun et al., 1992; Czech and Buxton, 1993) or by membrane depolarization in muscle cells (Wijesekara et al., 2006). Recent work indicates that energetic stress stabilizes another glucose transporter, Glut1, at the cell surface (Wu et al., 2013). Importantly, alterations in Glut transporter availability at the plasma membrane are associated with several human disorders. The insulin-dependent increase of plasma membrane–associated Glut4 is defective in type 2 diabetic patients (Zierath et al., 1996; Ryder et al., 2000). Moreover, Glut transporters, especially Glut1, are overexpressed in cancer cells, likely contributing to the increase in biomass production and tumor progression (Yun et al., 2009; Calvo et al., 2010). Thus, understanding the mechanisms regulating glucose transporter availability at the plasma membrane is of prime importance.

The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is an excellent model to investigate cellular adaptation to nutritional signals. In contrast to mammalian cells that are exposed to a relatively constant supply of nutrients, this unicellular organism evolved adaptive mechanisms to cope with highly variable nutrient availability in the environment (Smets et al., 2010). In particular, its genome encodes 20 hexose transporters that display various affinities toward their substrates, transport kinetics, and specific regulations. This warrants an efficient use of glucose over the broad range of concentrations they can encounter in the wild (Kruckeberg, 1996; Reifenberger et al., 1997). A well-known regulation of hexose transporters occurs at the transcriptional level, with multiple expression patterns favoring cell adaptability to variations in sugar availability.

Additionally, glucose also controls the abundance of carbon source transporters by regulating their endocytosis. Glucose induces the endocytosis of alternative carbon source transporters to ensure that glucose is used in priority when available (Medintz et al., 1996; Horak and Wolf, 1997; Lucero and Lagunas, 1997; Paiva et al., 2002; Ferreira et al., 2005). Glucose also triggers the endocytosis of the high-affinity glucose transporters Hxt2 and Hxt6, which are no longer required when glucose is present at high concentrations (Kruckeberg et al., 1999; Nikko and Pelham, 2009). Thus, by selectively remodeling the landscape of transporters present at the plasma membrane, endocytosis allows the efficient use of nutrients and is thus a core component of cell adaptation.

The selective endocytosis of transporters requires their prior ubiquitylation by the Nedd4-like E3 ubiquitin ligase Rsp5 (Hein et al., 1995; MacGurn et al., 2012). This posttranslational modification acts as a molecular signal that drives transporter internalization and progression in the endocytic pathway. Accordingly, glucose promotes the ubiquitylation of several alternative carbon source transporters, such as Gal2 (galactose), Mal61 (maltose), and Jen1 (lactate; Medintz et al., 1998; Horak and Wolf, 2001; Paiva et al., 2009).

Rsp5 uses adaptor proteins that contribute to the specificity and the timing of transporter ubiquitylation with respect to the physiology of the cell. Particularly, a family of arrestin-related trafficking adaptors (ARTs), related to visual/β-arrestins of metazoans, is crucial for stress- or nutrient-regulated endocytosis of transporters (Lin et al., 2008; Nikko et al., 2008; Becuwe et al., 2012a; Piper et al., 2014). The function of arrestin-related proteins is regulated by nutrient signaling pathways, allowing control of transporter endocytosis by nutritional challenges (O’Donnell et al., 2010, 2015,; MacGurn et al., 2011; Merhi and André, 2012). For instance, the glucose-induced endocytosis of Hxt6 requires the ART Rod1/Art4 (Nikko and Pelham, 2009), whose function is regulated by the yeast 5′ AMP-activated kinase (AMPK) orthologue Snf1 (Becuwe et al., 2012b; O’Donnell et al., 2015; Llopis-Torregrosa et al., 2016).

Here, we examine the mechanism governing endocytosis upon glucose deprivation. We show that in this condition, several high-affinity glucose transporters are induced, but unexpectedly, they are subsequently endocytosed and degraded after a few hours, possibly because of the lack of substrate to transport. Their endocytosis depends on a single ART protein, Csr2/Art8, which is regulated by glucose availability at multiple levels. Csr2 is the first yeast ART regulated at the transcriptional level, a process that involves the yeast AMPK Snf1. This transcriptional regulation renders Csr2 expression restricted to glucose-depleted conditions. Csr2 is further regulated at the posttranslational level: glucose replenishment switches Csr2 from an active, ubiquitylated form to an inactive, deubiquitylated, and phosphorylated form that associates with 14-3-3 proteins, in a process that involves protein kinase A (PKA). These data establish novel regulatory mechanisms by which ART proteins control endocytosis.

Results

Glucose depletion signals endocytosis of the high-affinity hexose transporters Hxt6 and Hxt7

We investigated the molecular events responsible for transporter endocytosis in glucose-deprived cells. Hxt6 is a high-affinity hexose transporter that is barely detectable in cells grown in glucose medium and becomes expressed upon switching cells to very low glucose or glucose-free medium (Ozcan and Johnston, 1995, 1996; Liang and Gaber, 1996; Ye et al., 2001). Accordingly, upon transfer to lactate-containing medium (a nonfermentable carbon source that supports growth by oxidative phosphorylation), Hxt6 was expressed and targeted to the plasma membrane (Fig. 1 A), but it subsequently exhibited a complete vacuolar localization after 24 h. Hxt7, another high-affinity hexose transporter that is nearly identical to Hxt6 and displays a comparable transcriptional regulation, behaved similarly (Fig. 1 A). Hxt6 was also endocytosed when cells were switched to a medium containing ethanol (another nonfermentable carbon source) or no carbon source (Fig. 1 B). Thus, Hxt6 endocytosis did not correlate with growth arrest and was likely triggered by glucose removal rather than by the presence of lactate. Western blots on total cell lysates confirmed a decrease in Hxt6-GFP abundance over time and the coincident appearance of a GFP-containing degradation product, originating from the partial vacuolar degradation of Hxt6-GFP (Fig. 1 C). Consistent with regulation by endocytosis, Hxt6-GFP degradation was strongly affected in the endocytic mutant vrp1Δ (end5Δ; Munn et al., 1995) or in the rsp5 hypomorphic mutant npi1 (Hein et al., 1995; Fig. 1 C). Therefore, Hxt6 is transiently expressed at the plasma membrane upon glucose depletion and is subsequently endocytosed and degraded in a ubiquitin- and Rsp5-dependent manner.

Figure 1.

Csr2 regulates the endocytosis of the high-affinity hexose transporters Hxt6 and Hxt7 upon a switch to a glucose-deprived medium. (A) Localization of endogenously GFP-tagged Hxt6 and Hxt7 in cells grown overnight in glucose (Glc medium (exponential phase) and switched to lactate-containing medium for the indicated times. PM, plasma membrane; V, vacuole. (B) Localization of Hxt6-GFP in WT cells grown on glucose medium and switched to the indicated media. (C) WT, vrp1Δ, and npi1 cells expressing Hxt6-GFP were grown in the indicated conditions. Total cell lysates were immunoblotted with anti-GFP and anti-PGK (phosphoglycerate kinase; used as a loading control) antibodies. Free GFP: originates from the vacuolar degradation of full-length Hxt6-GFP. (D) Localization of Hxt6-GFP in WT, 9-arrestinΔ and 9-arrestinΔ mutant cells complemented with a plasmid encoding either Ecm21/Art2 or Csr2/Art8. (E) Localization of Hxt6-GFP in WT and csr2-1 mutant cells in the indicated growth conditions. (F) From the experiment presented in E, total cell lysates were prepared and immunoblotted. (G) Localization of Hxt7-GFP in WT and csr2-1 mutant cells in the indicated growth conditions. (H) From the experiment presented in G, total cell lysates were prepared and immunoblotted. (I) Western blot signals were quantified using ImageJ (n ≥ 3 independent experiments); the ratio of the free GFP signal over the total GFP signal (7 h lactate time point) is represented (±SEM) for Hxt6-GFP (orange) and Hxt7-GFP (purple). **, P < 0.01.

The ART protein Csr2 is required for Hxt6 endocytosis in glucose-depleted medium

ART family adaptor proteins assist Rsp5 in its functions in endocytosis (Nikko et al., 2008; Nikko and Pelham, 2009; Hatakeyama et al., 2010; O’Donnell et al., 2010, 2015; MacGurn et al., 2011; Becuwe et al., 2012b; Merhi and André, 2012; Karachaliou et al., 2013; Alvaro et al., 2014). Accordingly, in a strain lacking nine ART genes (Nikko and Pelham, 2009), Hxt6 was no longer endocytosed upon transfer to lactate medium (Fig. 1 D).

The expression of a single ART protein, Csr2/Art8, but not its close paralogue Ecm21/Art2, restored Hxt6 endocytosis in the 9-arrestin mutant (Fig. 1 D). The deletion of CSR2 altered transporter trafficking and degradation in these conditions, but not that of ECM21 (Fig. S1, A and B), showing that Csr2 is required for Hxt6 endocytosis. However, in the csr2Δ mutant, Hxt6-GFP was expressed to a much lower level compared with the wild-type (WT) strain, which may interfere with our conclusions (Fig. S1, A and B). Of note, only the expression of Hxt6 and Hxt7 appeared affected, not that of other transporters (Fig. S1 C; see also Fig. 4). The Hxt6 expression defect observed in a csr2Δ strain was not due to a nonconventional role of Csr2 in transporter expression, because it could not be suppressed by various Csr2-encoding plasmids (Fig. S1, D–F). To circumvent this problem, we generated and characterized another CSR2 mutant allele, which we named csr2-1, in which Hxt6 expression was comparable with that in WT cells (Fig. S1, G–I). Reassessing the localization and stability of Hxt6-GFP in the csr2-1 strain upon transfer to lactate medium confirmed the requirement of Csr2 for Hxt6-GFP endocytosis and degradation (Fig. 1, E, F, and I), although we cannot formally rule out a minor contribution of other ARTs. Similar results were obtained with Hxt7, which was also endocytosed and degraded in a Csr2-dependent fashion (Fig. 1, G–I).

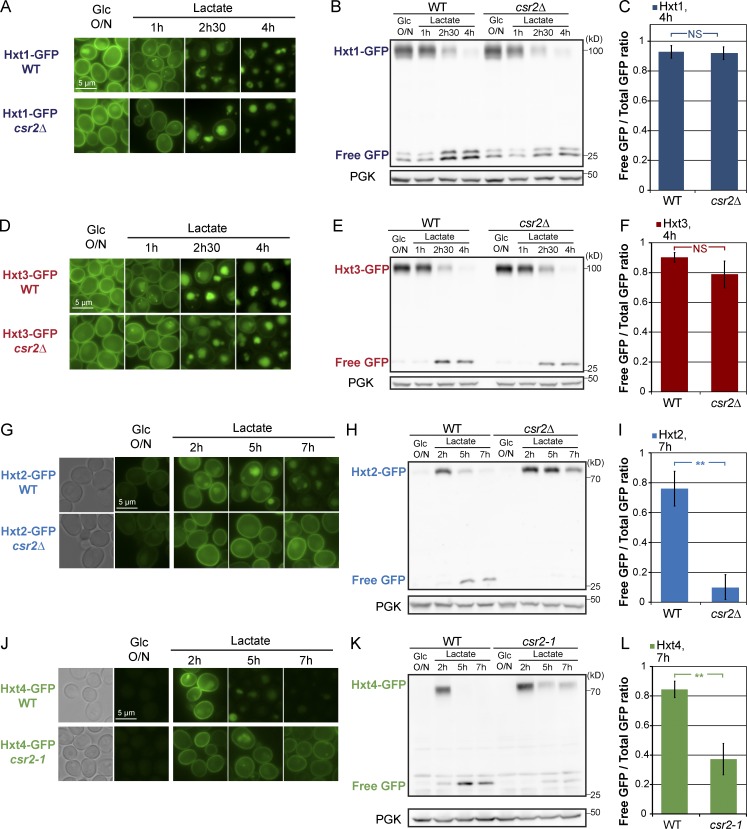

Figure 4.

The endocytosis of other high-affinity hexose transporters during glucose deprivation also involves Csr2. (A) WT and csr2Δ cells expressing endogenously tagged Hxt1-GFP were grown as indicated and imaged for GFP fluorescence. (B) Total cell lysates from the experiment presented in A were immunoblotted using the indicated antibodies. (C) Western blot signals were quantified using ImageJ (n = 3 independent experiments); the ratio of the free GFP signal over the total GFP signal (±SEM) is represented (for the 4-h lactate time point). (D) WT and csr2Δ mutant cells expressing endogenously tagged Hxt3-GFP were grown as indicated and imaged for GFP fluorescence. (E) Total cell lysates from the experiment presented in D were immunoblotted using the indicated antibodies. (F) Western blot signals were quantified (± SEM) as in C (n = 3 independent experiments; NS, not significant). (G) WT and csr2Δ cells expressing endogenously tagged Hxt2-GFP were grown as indicated and imaged for GFP fluorescence. (H) Total cell lysates from the experiment presented in G were immunoblotted using the indicated antibodies. (I) Western blot signals were quantified (± SEM) as in C using the 7-h lactate time point (n = 3 independent experiments; **, P < 0.01). (J) WT and csr2-1 cells expressing endogenously tagged Hxt4-GFP were grown as indicated and imaged for GFP fluorescence. (K) Total cell lysates from the experiment presented in J were immunoblotted using the indicated antibodies. (L) Western blot signals (± SEM) were quantified as in C using the 7-h lactate time point (n = 3 independent experiments; **, P < 0.01).

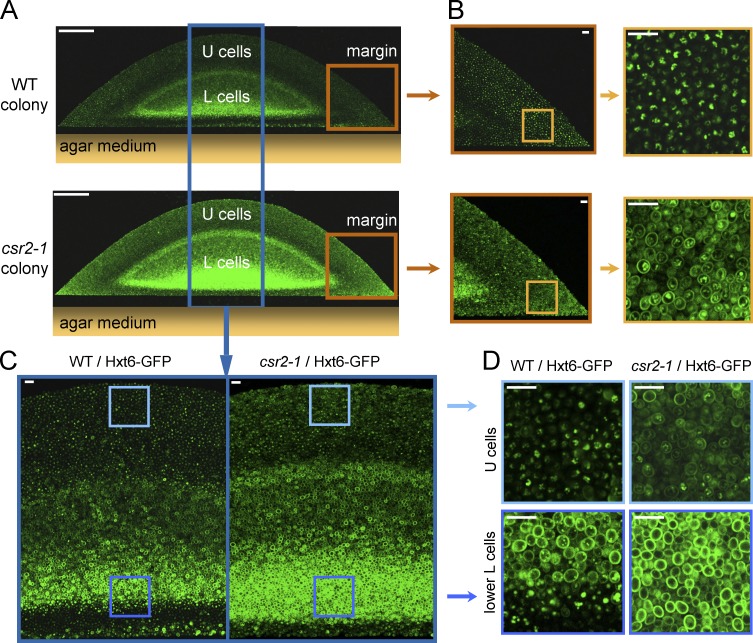

Csr2 regulates Hxt6 homeostasis in the context of a yeast colony

Previous work established that yeast colonies constitute a complex, stratified system composed of layers of yeast cells in distinct physiological and metabolic states (Váchová et al., 2009; Čáp et al., 2012). Whereas upper cells are glycolytic with a low respiratory metabolism, lower cells behave oppositely (Palková et al., 2014; Čáp et al., 2015). Lower cells can be further stratified into “upper” and “lower” lower cells (Podholová et al., 2016). The existence of metabolic gradients across a colony suggested that transporter endocytosis might occur at the frontier of different subpopulations. Yeast expressing Hxt6-GFP was grown on respiratory medium, and cross sections of 4-d-old differentiated colonies were observed using two-photon excitation confocal microscopy (Váchová et al., 2009). The results show that Hxt6 was expressed mostly in lower cells (Fig. 2 A), where it localized to the plasma membrane (Fig. 2, C and D). This is consistent with the fact that these cells rely on respiratory metabolism for survival. In upper cells, which are respirofermenting cells (Čáp et al., 2015), the global Hxt6-GFP fluorescence decreased, and the fluorescent signal localized mostly to the vacuole. Performing the same experiment on a csr2-1 background revealed an increase in global Hxt6-GFP fluorescence of the colony, as well as increased Hxt6-GFP plasma membrane localization in upper cells and in cells at the margins of the colony (Fig. 2, B and D). Furthermore, Hxt6-GFP was also much more expressed in yeast cells proximal to the agar medium in the csr2-1 mutant (lower layers of lower cells; Fig. 2, C and D). These results lend support to a key role of Csr2 in Hxt6 homeostasis in the physiological context of a yeast colony.

Figure 2.

Csr2 regulates Hxt6 homeostasis in the context of a yeast colony. (A) Vertical transverse sections of a WT and a csr2-1 colony expressing Hxt6-GFP and grown on glycerol-ethanol complete respiratory medium, obtained by two-photon confocal imaging. Two individual images spanning the width of the colonies were acquired and assembled after acquisition to generate the composite image shown. Bars, 100 µm. (B) Detailed views of the fluorescence at the margin of each colony. Bars, 10 µm. (C) Detailed view of the central region of the colonies. Two individual images spanning the height of the colonies were acquired and assembled after acquisition to generate the composite image shown. Bars, 10 µm. (D) Detailed view of U (upper) cells and lower L (lower) cells as displayed in C. Bars, 10 µm.

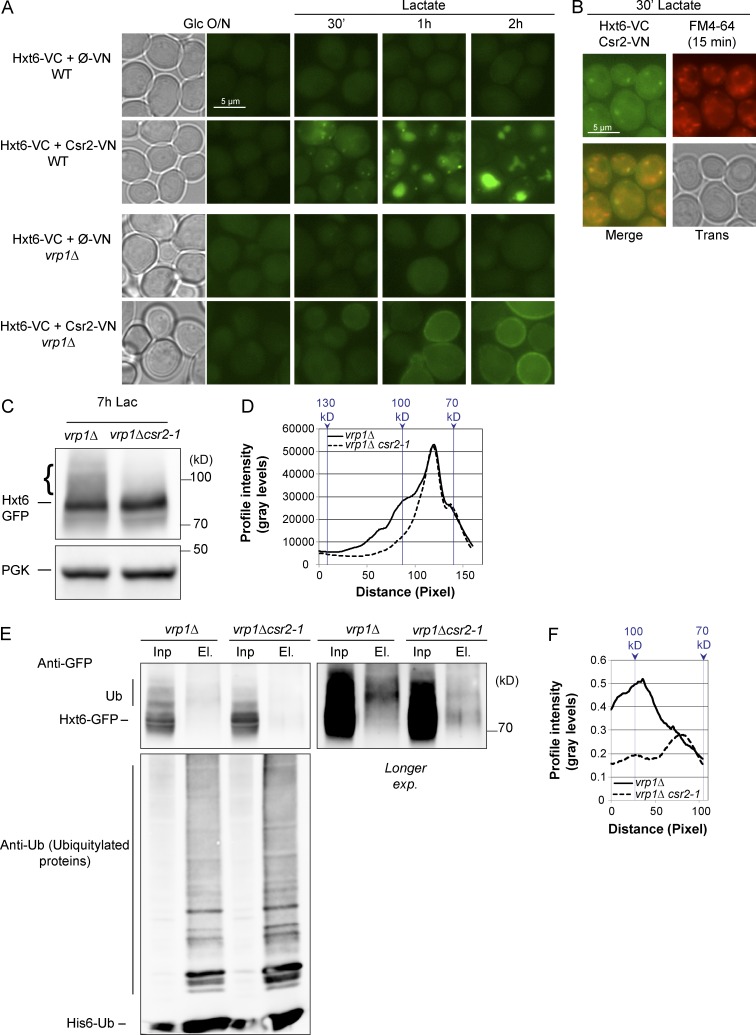

Csr2 interacts with Hxt6 in vivo and promotes its ubiquitylation

Using bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC; Hu et al., 2002), we obtained evidence of in vivo interaction between Csr2 and Hxt6 (Fig. 3 A). The N- and C-terminal fragments (VN and VC) of the Venus fluorescent protein were fused to the C termini of Csr2 and Hxt6, respectively. In these experiments, Hxt6 was tagged at its chromosomal locus to keep its endogenous regulation, whereas Csr2-VN was expressed from a centromeric (low-copy) plasmid and driven by the strong pTEF1 promoter (translation elongation factor-1A) because the endogenous expression level of Csr2 was too weak for BiFC analysis (not depicted). Early after inducing Hxt6 endocytosis by switching the cells to lactate medium (30 min), a fluorescent signal appeared in cytoplasmic punctate structures, which was dependent on the expression of Csr2-VN (Fig. 3 A). This signal partially colocalized with endosomes, as determined by the use of the endocytic tracer FM4-64 (Vida and Emr, 1995; Fig. 3 B). A vacuole-localized fluorescence signal appeared over time and became the major localization of the complex 2 h after transfer to lactate medium (Fig. 3 A). This may be caused by the irreversible reconstitution of the Venus protein upon interaction between Csr2 and Hxt6 (Hu et al., 2002). In the endocytic mutant, vrp1Δ, the reconstituted Csr2-VN/Hxt6-VC fluorescent complex localized to the plasma membrane, suggesting that the lack of a plasma membrane–localized signal in WT cells may be due to the time required for the reconstituted Venus protein to become fluorescent (Hu et al., 2002; Fig. 3 A). Of note, no cytosolic punctae were observed in the vrp1Δ mutant, suggesting that the latter originate solely from endocytosis. Thus, Csr2 can interact in vivo with Hxt6 during its endocytosis.

Figure 3.

Csr2 interacts with Hxt6 in vivo and promotes its ubiquitylation. (A) WT or vrp1Δ cells expressing endogenously tagged Hxt6-VC and either pTEF-driven VN alone (negative control) or VN fused to Csr2 were grown as indicated and imaged by fluorescence microscopy. (B) WT cells expressing endogenously tagged Hxt6-VC and pTEF-driven Csr2-VN were grown in glucose medium and transferred to lactate medium for 30 min. At t = 15 min, the endocytic tracer FM4-64 was added for 15 min before imaging. (C) Total cell lysates from vrp1Δ and vrp1Δ csr2-1 cells expressing Hxt6-GFP grown in the indicated conditions were immunoblotted. Brace, higher molecular mass species of Hxt6-GFP accumulate in the vrp1Δ. (D) Line-scan profile of the immunoblot displayed in C. Continuous line, vrp1Δ lane; dashed line, vrp1Δ csr2-1 lane. (E) vrp1Δ and vrp1Δ csr2-1 cells expressing endogenously tagged Hxt6-GFP and His6-tagged ubiquitin (Ub) were grown for 6 h in lactate medium, and ubiquitylated proteins were affinity-purified. Input (Inp) and ubiquitin-purified fractions (El.) were immunoblotted using anti-GFP and anti-ubiquitin (purification control) antibodies. exp., exposure. (F) Line-scan profile of the immunoblot displayed in E. Continuous line, vrp1Δ lane; dashed line, vrp1Δ csr2-1 lane.

Csr2, as a member of the ART family, was proposed to act as an adaptor protein for Rsp5 to mediate cargo ubiquitylation (Lin et al., 2008; Nikko et al., 2008; Polo and Di Fiore, 2008; Nikko and Pelham, 2009). To study Hxt6 ubiquitylation, we used an endocytosis-deficient strain (vrp1Δ) that favors the detection of ubiquitylated cargoes. Indeed, higher molecular mass species of Hxt6-GFP were readily observed in crude extracts of the vrp1Δ mutant, which were absent in the rsp5 mutant npi1 (see Fig. 1 C). Moreover, this smear was much less present in the double vrp1Δ csr2-1 mutant, suggesting that Csr2 might contribute to Hxt6 ubiquitylation (Fig. 3, C and D). This was confirmed by purifying, in denaturing conditions, all ubiquitylated proteins from vrp1Δ and vrp1Δ csr2-1 strains expressing polyhistidine-tagged ubiquitin. In the purified fraction of the vrp1Δ single mutant, higher molecular mass species of Hxt6-GFP were enriched over nonmodified Hxt6-GFP, but this was not the case in the vrp1Δ csr2-1 mutant (Fig. 3, E and F), showing that Csr2 promotes Hxt6 ubiquitylation.

Csr2 targets other high-affinity glucose transporters for endocytosis in glucose-depleted medium

We studied the localization of other glucose transporters (Hxt1-Hxt5) fused to GFP in cells grown during the exponential phase in glucose-containing medium and during adaptation to a glucose-deprived medium (Fig. S2 A). Only Hxt1 and Hxt3 were expressed in glucose medium, consistent with their function as low-affinity glucose transporters (Ko et al., 1993; Reifenberger et al., 1997; Ozcan and Johnston, 1999). Incubation in lactate medium led to their endocytosis and degradation (Fig. S2 A), in line with previous studies (Snowdon et al., 2009; Roy et al., 2014). However, their endocytosis and degradation were independent of Csr2 (Fig. 4, A–F), suggesting a distinct regulation. Hxt5, which displays a moderate affinity toward glucose (Diderich et al., 2001), was expressed after transfer to lactate medium and accumulated at the plasma membrane over time (Fig. S2 A), consistent with its function in glucose uptake upon glucose recovery (Bermejo et al., 2010). A fraction of Hxt5 was targeted to the vacuole and degraded 7–24 h after transfer to lactate medium, but again, this did not require Csr2 (Fig. S2, B–D).

In contrast, Hxt2 and Hxt4, which display a moderate to high affinity toward glucose, followed a similar regulation as Hxt6 and Hxt7. Both transporters were induced upon transfer to lactate medium and became endocytosed and degraded after a few hours in a Csr2-dependent fashion (Fig. S2 A and Fig. 4, G–L). Thus, Csr2 primarily targets high-affinity glucose transport systems for endocytosis after glucose depletion.

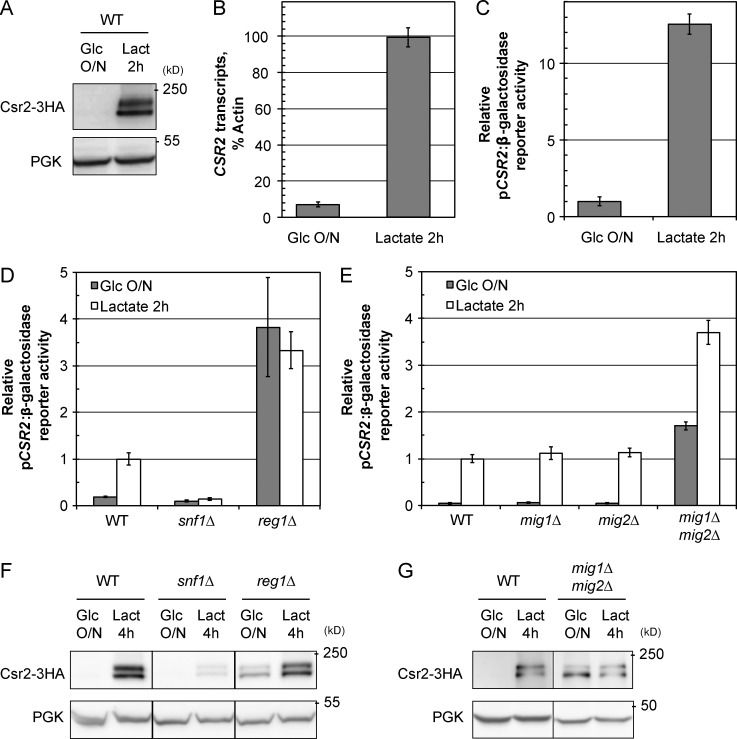

Csr2 transcription is up-regulated in conditions that trigger endocytosis

We then investigated the mechanism whereby Csr2 coordinates transporter endocytosis with glucose availability, starting with a possible regulation of its expression (Khanday et al., 2002). Csr2 was barely detectable in extracts from cells grown in glucose medium but became expressed within 2 h after transfer to lactate medium (Fig. 5 A). This correlated with an increase of more than 14-fold in CSR2 transcripts in lactate versus glucose medium (Fig. 5 B). The use of a β-galactosidase reporter revealed that the CSR2 promoter was activated to a similar extent during glucose depletion (Fig. 5 C). Thus, CSR2 transcription is induced in conditions that trigger the endocytosis of the cargoes it regulates.

Figure 5.

Glucose represses CSR2 expression. (A) Cells expressing endogenously tagged Csr2-3HA were grown as indicated, and total cell lysates were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. Lact, lactate. (B) Total RNA was prepared from cells that are WT for CSR2, and the CSR2 transcript was detected by quantitative RT-PCR. Data represent the mean of four independent biological replicates (each with two technical replicates) ± SEM. (C) β-Galactosidase activity of cells expressing the lacZ reporter gene driven by the CSR2 promoter, grown as indicated. Data were normalized to β-galactosidase activity in glucose-grown cells and are the mean of three independent biological replicates (each with three technical replicates) ± SEM. (D) β-Galactosidase activity (± SEM) of WT, snf1Δ, and reg1Δ cells expressing the pCSR2:lacZ fusion. (E) β-Galactosidase activity (± SEM) of WT, mig1Δ, mig2Δ, and mig1Δ mig2Δ cells expressing the pCSR2:lacZ fusion. (F) WT, snf1Δ, and reg1Δ cells expressing endogenously tagged Csr2-3HA grown as indicated, and total cell lysates were immunoblotted with anti-HA and anti-PGK antibodies. (G) WT and mig1Δ mig2Δ cells expressing endogenously tagged Csr2-3HA grown as indicated, and total cell lysates were immunoblotted with anti-HA and anti-PGK antibodies.

CSR2 expression is regulated by glucose availability through the Snf1/protein phosphatase 1 pathway and its downstream effectors Mig1 and Mig2

Many genes are repressed by glucose through a glucose-sensing pathway composed of the yeast AMPK orthologue Snf1 and its counteracting protein phosphatase 1 complex (Glc7/Reg1; Gancedo, 2008; Zaman et al., 2009). In the snf1Δ mutant, the CSR2 promoter remained repressed upon glucose removal, whereas in the reg1Δ mutant, CSR2 was constitutively derepressed despite the presence of glucose (Fig. 5 D). Thus, the kinase Snf1 is required for the glucose-mediated repression of CSR2.

The Snf1/protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) pathway controls the transcription of many genes through several transcriptional effectors (Broach, 2012). The transcriptional repressor Mig1 is a target of Snf1 and is responsible for the glucose-mediated repression of many Snf1-regulated genes. Mig2 is another repressor that sometimes cooperates with Mig1 in this transcriptional regulation (Westholm et al., 2008). We observed that the CSR2 promoter was strongly derepressed in the mig1Δmig2Δ double mutant, even in the presence of glucose, whereas none of the single mutants were affected (Fig. 5 E). Thus, the Snf1/PP1 glucose signaling pathway regulates CSR2 at the transcriptional level as a function of glucose availability through the redundant action of its downstream effectors Mig1 and Mig2. Notably, the abundance of the Csr2 protein in these various mutants was in general agreement with the observed activity of the CSR2 promoter (Fig. 5, F and G). Minor variations were observed, which may be due to additional layers of regulation such as translation rate or mRNA stability (Braun et al., 2015).

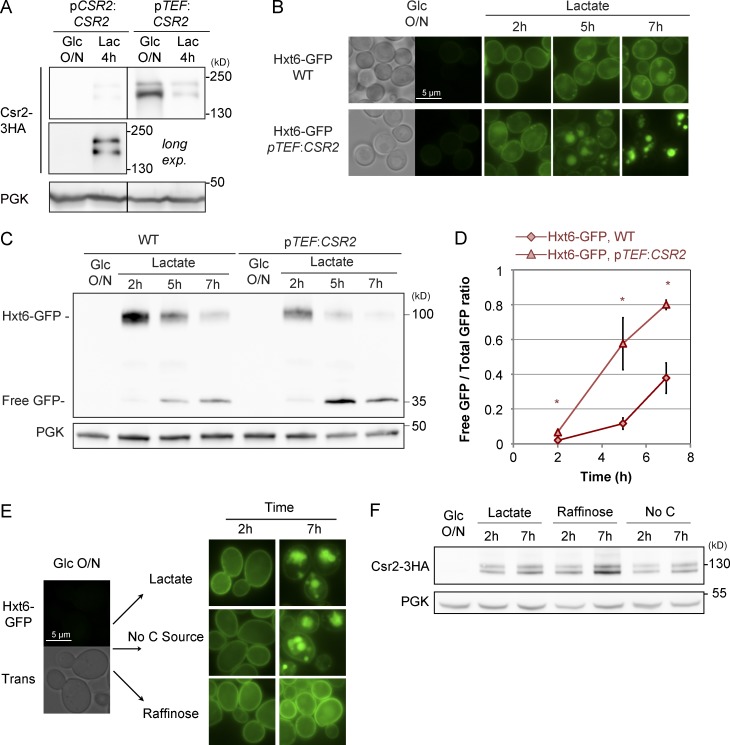

CSR2 overexpression does not trigger Hxt6 endocytosis but increases its efficiency

To study the impact of the transcriptional regulation of CSR2 on Hxt6 endocytosis, we interfered with the endogenous expression of CSR2 through the use of the strong TEF1 promoter, leading to Csr2 expression in glucose medium (Fig. 6 A). Even though Csr2 expression was high in glucose medium and decreased upon transfer to lactate medium, it was always stronger than endogenously expressed Csr2. Csr2 overexpression led to faster endocytosis and degradation of Hxt6 upon transfer of cells to lactate medium (Fig. 6, B–D) indicating that Csr2 overexpression contributes to the overall efficiency of Hxt6 endocytosis.

Figure 6.

The transcriptional regulation of Csr2 contributes to the timing of Hxt6 endocytosis. (A) Cells expressing endogenously 3HA-tagged Csr2 driven by its endogenous promoter or the strong TEF1 promoter were grown as indicated, and total cell lysates were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (top) Samples were on the same gel and exposed for the same amount of time. Middle, longer exposure. (B) Localization of endogenously GFP-tagged Hxt6 in cells expressing Csr2, driven either by its endogenous promoter or by the TEF promoter, grown as indicated. (C) Total cell lysates prepared from the experiment depicted in B were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (D) Western blots signal were quantified using ImageJ (n = 3 independent experiments); the ratio of the free GFP signal over the total GFP signal at various time points is represented ± SEM (*, P < 0.05). Diamonds, WT strain; triangles, pTEF-CSR2 strain. (E) Localization of Hxt6-GFP in WT cells grown in glucose medium and switched to the indicated media. (F) Cells expressing endogenously 3HA-tagged Csr2 driven by its endogenous promoter were grown as indicated, and total cell lysates were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies.

Unexpectedly, while studying the nutritional signals responsible for Hxt6 endocytosis, we found that Hxt6 was endocytosed when cells were transferred to a medium containing lactate or ethanol or even to a medium lacking any carbon source (see Fig. 1 B), but not when transferred to raffinose-containing medium (Fig. 6 E). Raffinose is a trisaccharide that is slowly hydrolyzed in the medium by invertase, a secreted enzyme, into melibiose and fructose, only the latter of which can be used as a carbon source (Lindegren et al., 1944). Raffinose medium is thus sensed by yeast cells as containing a low hexose concentration (2% raffinose concentration being equivalent to 0.2% glucose; Ozcan and Johnston, 1995; Kim et al., 2003). In these conditions, Hxt6 mediates hexose uptake (Liang and Gaber, 1996) and is maintained at the plasma membrane (Fig. 6 E). Yet Csr2 was expressed in these conditions (Fig. 6 F). Therefore, although Csr2 is essential for Hxt6 endocytosis, its expression is not sufficient to trigger transporter endocytosis. This reveals the existence of another level of regulation of Hxt6 endocytosis, possibly by the availability of substrates and/or its transport activity.

Ubiquitylation as a second level of regulation of Csr2 by glucose availability

The Csr2 protein migrated as a doublet by Western blot (Fig. 5, A, F, and G). ART proteins are ubiquitylated by Rsp5 (Lin et al., 2008; Becuwe et al., 2012a), and Csr2 is an in vitro substrate of Rsp5 (Kee et al., 2006), raising the possibility that this pattern is due to Csr2 ubiquitylation. The purification of all ubiquitin conjugates from cells coexpressing 3HA-tagged Csr2 and His6-tagged ubiquitin revealed that the slower migrating band corresponded to ubiquitin-modified Csr2 (Fig. 7 A). Consistently, this band was no longer detected in the hypomorphic rsp5 mutant npi1 (Fig. 7 B) or upon mutations of proline-tyrosine (PY) motifs on Csr2, which are canonical sites predicted to interact with Rsp5 (Csr2-PYm: Y796A, Y1116A; Fig. 7 C). Thus, the upper band of the Csr2 doublet results from its ubiquitylation by Rsp5.

Figure 7.

Csr2 ubiquitylation is regulated by glucose availability. (A) Purification of ubiquitylated proteins from cells coexpressing Csr2-3HA and histidine-tagged ubiquitin and grown in lactate medium for 4 h. Lys, lysate; Unb, unbound fraction; El, eluates. Protein extracts were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (B) WT and npi1 (rsp5 mutant) cells expressing endogenously 3HA-tagged Csr2 were grown in glucose medium and switched to lactate-containing medium for 4 h, before glucose was added back. Total cell lysates were prepared and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (C) WT cells expressing a plasmid-encoded Csr2-3HA or its mutated variant, Csr2(PYm)-3HA (mutations Y796A and Y1116A) were grown and processed as in B. (D) Design of the quantitative proteomics experiment. Lactate-grown cells expressing His6-tagged ubiquitin were treated or not with 2% glucose for 10 min. Ubiquitylated proteins were then purified in both conditions, identified and quantified by quantitative, label-free mass spectrometry. LC-MS/MS, liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. (E) Volcano plot displaying the log2 value of the ratio of protein abundance (label-free quantification [LFQ] intensity) in the presence or absence of glucose, plotted against −log10 of the p-value of the t test for each protein (four independent biological replicates). The line indicates the threshold for a 5% false discovery rate.

Strikingly, this ubiquitylated fraction of Csr2 vanished upon glucose treatment (Fig. 7, B and C). This was confirmed by an unbiased proteomics approach in which Csr2 was identified as a protein whose ubiquitylation is influenced by glucose availability (Fig. 7, D and E). In conclusion, in addition to the transcription-based regulation of CSR2, this dynamic ubiquitylation represents a second glucose-regulated event in the regulation of Csr2.

Glucose treatment led not only to loss of Csr2 ubiquitylation but also to the rapid disappearance of Csr2 (Fig. 7, B and C). 3HA-tagged Csr2 is a short-lived protein, with a comparable half-life in lactate and glucose medium (Fig. S3, A and B), suggesting that its disappearance in response to glucose does not involve a glucose-induced degradation process but rather is due to a transcriptional shutdown of CSR2 followed by the degradation of preexisting Csr2. This degradation involved the proteasome: treatment of cells with the proteasome inhibitor MG-132 led to Csr2-3HA stabilization, in a nonubiquitylated state after glucose addition (Fig. S3 A). However, this degradation did not require Rsp5, because Csr2 was degraded at comparable levels in the npi1 mutant or upon mutation of its PY motifs (Fig. 7, B and C). This suggests the involvement of an additional ubiquitin ligase. However, we did not pursue this line of investigation. Indeed, Csr2 stability was influenced by the epitope used for tagging; for instance, a tandem affinity purification (TAP; = calmodulin binding protein–TEV–protein A)–tagged version of Csr2 caused a much slower degradation after glucose treatment (Fig. S3 C).

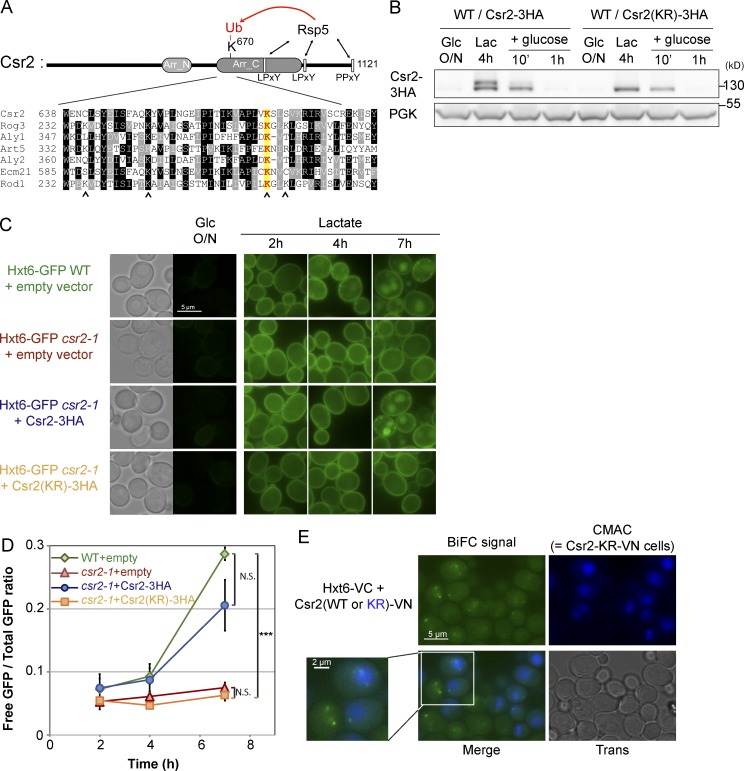

Csr2 ubiquitylation occurs on a conserved lysine of the arrestin-C domain and is required for its function in endocytosis

Initial studies reported that the ubiquitylation of ARTs promotes their activation (MacGurn et al., 2011; Becuwe et al., 2012b; Merhi and André, 2012; Karachaliou et al., 2013). Yet some ARTs can mediate endocytosis independently of their ubiquitylation (Alvaro et al., 2014; Crapeau et al., 2014). As a first step to understanding whether Csr2 ubiquitylation contributes to high-affinity glucose transporter endocytosis, we mapped the ubiquitylation site. Mass spectrometry analysis of a Csr2-3HA immunoprecipitate identified one Csr2 peptide that contained a ubiquitin remnant motif on residue K670 (K-ε-GG signature; Peng et al., 2003; Fig. S4 A). This residue was located at the beginning of the predicted arrestin-C domain and is conserved in at least seven other yeast ART proteins (Fig. 8 A). In particular, it is included among the four sites whose mutation abolished Rod1 ubiquitylation (Becuwe et al., 2012b). Mutation of this site (K670R) abolished Csr2 ubiquitylation (Fig. 8 B). Thus, Csr2 is ubiquitylated on a conserved residue of the arrestin-C domain upon glucose deprivation. Importantly, the Csr2(KR)-3HA mutant was degraded similarly to WT Csr2-3HA after glucose treatment (Fig. 8 B), further confirming that the Rsp5-mediated ubiquitylation of Csr2-3HA does not regulate its stability.

Figure 8.

Csr2 is ubiquitylated at a conserved site in the ART proteins and this is required for its function in endocytosis. (A, top) Schematic of the primary structure of the Csr2 protein showing potential arrestin-N domain (Becuwe et al., 2012a), arrestin-C domain (Pfam accession no. PF02752), LPxY and PPxY motifs, and the lysine residue identified as ubiquitylated by mass spectrometry (K670; see Fig. S4 A). (bottom) Partial alignment of seven ART proteins from S. cerevisiae showing the conservation of a lysine residue at this position. Arrowheads, residues whose combined mutation abolishes Rod1 ubiquitylation (Becuwe et al., 2012b). (B) Total cell lysates from WT cells expressing a plasmid-encoded Csr2-3HA or its mutated variant, Csr2(KR)-3HA (mutation K670R) were prepared at the indicated times and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (C) Localization of Hxt6-GFP in WT cells (carrying an empty plasmid) and csr2-1 mutant cells, transformed with either an empty plasmid, a plasmid carrying a WT Csr2-3HA, or the point mutant Csr2(KR)-3HA in the indicated growth conditions. (D) From the experiment depicted in C, total cell lysates were prepared and immunoblotted (see a representative immunoblot in Fig. S4 B). GFP signals were quantified at various time points and are plotted ± SEM (n = 3 independent experiments); p-values were calculated for the 7-h time point (***, P < 0.001). (E) WT cells expressing both endogenously tagged Hxt6-VC and either a pTEF-driven Csr2-VN or a pTEF-driven Csr2-KR-VN were grown in glucose medium and switched to lactate medium for 30 min. Csr2-KR-VN-expressing cells were labeled with the vacuolar dye CMAC, washed, and mixed with Csr2-VN-expressing cells. Both strains were imaged together by fluorescence microscopy in the green and blue channels. (left) Detailed view of the indicated cells.

The Csr2(KR) mutant could not restore Hxt6-GFP endocytosis, nor its degradation (Fig. 8, C and D, and Fig. S4 B) when expressed on a csr2-1 background. Therefore, Csr2 ubiquitylation is essential for its function in endocytosis in glucose-depleted conditions. Consequently, the loss of Csr2 ubiquitylation upon glucose replenishment probably leads to its inactivation. Interestingly, Csr2(KR)-VN still interacted with Hxt6-VC by BiFC, suggesting that Csr2 ubiquitylation is not a prerequisite for this interaction (Fig. 8 E).

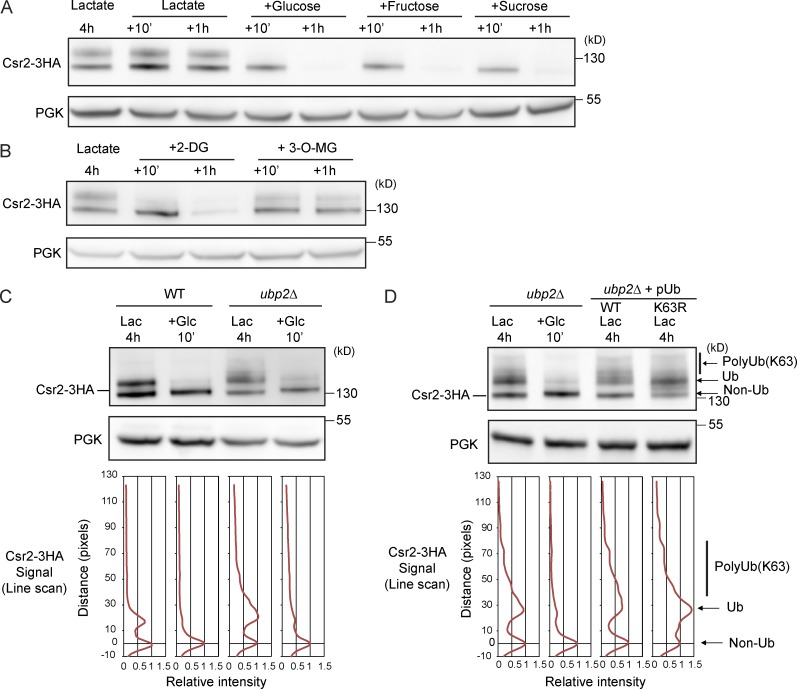

Phosphorylatable sugars regulate Csr2 ubiquitylation

To probe the signaling events whereby glucose regulates Csr2 ubiquitylation, we studied the effect of other sugars or glucose analogues. Fructose (which, like glucose, is a substrate of hexokinase and is metabolized by glycolysis) and sucrose (which is hydrolyzed in the extracellular medium into glucose and fructose by invertase) were equally as competent as glucose to mediate a change in Csr2 ubiquitylation (Fig. 9 A). The glucose analogue 2-deoxyglucose, which is also phosphorylated by hexokinase but cannot be further metabolized, also elicited the loss of Csr2 ubiquitylation (Fig. 9 B). In contrast, 3-O-methylglucose, which behaves as a nonphosphorylatable sugar, did not alter the Csr2 ubiquitylation pattern (Fig. 9 B). Csr2 ubiquitylation is therefore regulated by sugar phosphorylation during early steps of glycolysis, independently of the energy provided by sugar metabolism.

Figure 9.

Regulation of Csr2 ubiquitylation by sugar analogues and the ubiquitin-specific protease Ubp2. (A) Lactate-grown WT cells expressing endogenously tagged Csr2-3HA were treated with glucose, fructose, or sucrose or were nontreated (lactate). Total cell lysates were prepared and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (B) Same as A, except that cells were treated with 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) or 3-O-methylglucose (3-O-MG). (C, top) Total cell lysates from WT and ubp2Δ cells expressing endogenously tagged Csr2-3HA and grown as indicated were immunoblotted with anti-HA and anti-PGK antibodies. (bottom) Line scan showing band intensity as a function of the distance from the maximum of the indicated non-Ub Csr2 peak. (D, top) Total cell lysates from ubp2Δ cells expressing endogenously tagged Csr2-3HA and overexpressing either WT ubiquitin or K63R-ubiquitin were grown and treated as in C. (bottom) Line scan was performed as in C. Arrows on the right indicate the position of nonubiquitylated, ubiquitylated, and polyubiquitylated Csr2.

Interestingly, when expressed in glucose medium using the pTEF promoter, Csr2 was still ubiquitylated, albeit to a lesser extent than the endogenous Csr2 in lactate medium (see Fig. 6 A). This indicates that the loss of Csr2 ubiquitylation is part of an early glucose response. This is further supported by our observation that the loss of Csr2-TAP ubiquitylation after glucose treatment was only transient (see Fig. S3 C).

Ubp2 controls the topology of the ubiquitin modification on Csr2

We then aimed to dissect the mechanism responsible for the dynamic, glucose-regulated ubiquitylation of Csr2. Previous work demonstrated that Rsp5 physically interacts with Ubp2, a deubiquitylating enzyme that counteracts Rsp5 activity in the assembly of K63-linked ubiquitin chains (Kee et al., 2005). Additionally, in vitro ubiquitylated Csr2 was also a substrate of Ubp2 (Kee et al., 2006). However, the deletion of UBP2 only mildly affected the loss of Csr2 ubiquitylation in response to glucose (Fig. 9 C). Yet in lactate-grown ubp2Δ cells, a fraction of Csr2 was shifted up in its apparent size (Fig. 9 C). This may be due to increased ubiquitylation of Csr2, in line with the proposed role of Ubp2 in controlling ubiquitin chain length on Rsp5 substrates (Kee et al., 2005, 2006; Harreman et al., 2009; Erpapazoglou et al., 2012). Indeed, overexpression of a ubiquitin mutant unable to generate K63-linked chains (ubiquitin-K63R) interfered with this process and restricted the extent of this shift (Fig. 9 D). Thus, Ubp2 controls the extent of the K63-linked ubiquitin chain length generated by Rsp5 on Csr2. We further looked for the possible involvement of other deubiquitylating enzymes in Csr2 deubiquitylation upon glucose treatment, using single or multiple ubiquitin isopeptidase mutants because a level of redundancy was anticipated from previous studies (Amerik et al., 2000). However, the disappearance of ubiquitylated Csr2 in response to glucose was maintained in all of the mutants studied (unpublished data).

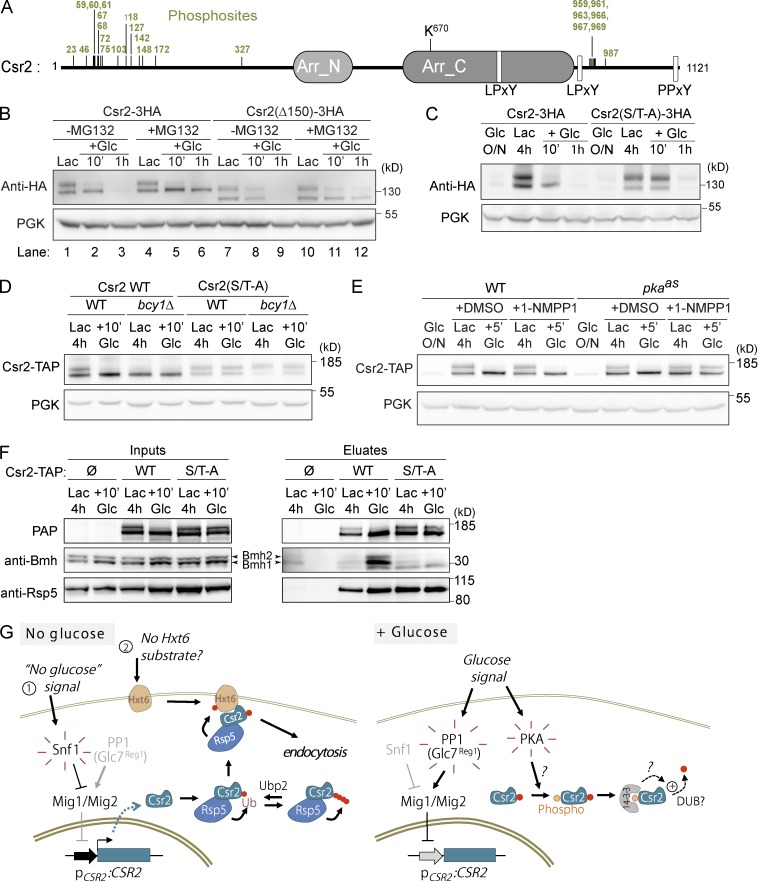

Glucose-regulated deubiquitylation of Csr2 involves its phosphorylated N-terminal region

ART ubiquitylation can be negatively regulated by their phosphorylation (Becuwe et al., 2012b; Merhi and André, 2012). We identified several phosphorylation sites (serine [Ser]/threonine [Thr]) by mass spectrometry after immunoprecipitation of Csr2-3HA. Most of them clustered within two regions of the protein (i.e., around residues 1–150 and 950–990; Fig. 10 A). To investigate whether these contribute to the regulation of Csr2 ubiquitylation, we deleted the first 150 residues of Csr2 (Csr2-Δ150). Csr2-Δ150 was functional and restored Hxt6-GFP endocytosis when expressed in a csr2-1 mutant (see Fig. S5 A) but remained ubiquitylated even after the addition of glucose (Fig. 10 B, lane 8). This became even more evident upon stabilization of the protein with MG-132: whereas Csr2 was stabilized as a nonubiquitylated protein, Csr2-Δ150 was stabilized as both ubiquitylated and nonubiquitylated (Fig. 10 B, compare lanes 6 and 12). This ubiquitylation still occurred on K670, as determined by the lack of ubiquitylation of a Csr2-Δ150, K670R mutant (Fig. S5 B).

Figure 10.

Mechanism of glucose-induced deubiquitylation of Csr2. (A) Schematic of the primary sequence of Csr2 indicating, in green, the position of phosphorylated sites identified by mass spectrometry on a Csr2-3HA immunoprecipitate. (B) Glucose-grown cells expressing a plasmid-encoded full-length Csr2-3HA or a construct lacking its first 150 residues (Csr2-Δ150-3HA; pdr5Δ background) were switched to lactate-containing medium. Cells were then treated with MG-132 (lanes 4 and 10) or not (lanes 1 and 7) for 30 min before glucose was added (lanes 2 and 3, 5 and 6, 8 and 9, and 11 and 12). Total cell lysates were prepared and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (C) WT cells expressing an HA-tagged, plasmid-encoded Csr2-3HA or mutated for several Ser/Thr residues were grown as indicated, and total cell lysates were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (D) WT or bcy1Δ cells expressing either a plasmid-encoded Csr2-TAP or Csr2-(S/T-A)-TAP were grown as indicated, and total cell lysates were immunoblotted using peroxidase anti-peroxidase (PAP) and anti-PGK antibodies. (E) The PKA mutant strain (pkaas) or its WT control, both expressing a Csr2-TAP construct, were grown overnight in glucose medium (exponential phase) and transferred to lactate medium for 4 h in the presence of either 50 µM 1NM-PP1 or an equivalent volume of DMSO. Then, glucose was added to the culture. Total cell lysates were prepared and immunoblotted using the indicated antibodies. (F) WT cells carrying an empty vector, a vector encoding Csr2-TAP or Csr2-(S/T-A)-TAP were grown in lactate-containing medium, before glucose was added. Cells were lysed (inputs) and TAP constructs were affinity-purified (eluates). The presence of Csr2 was revealed using PAP antibodies and that of Bmh1/2 and Rsp5 using specific antibodies. (G) Working model for the regulation of Csr2 by glucose availability. Left: In the absence of glucose, activation of the yeast AMPK kinase Snf1 inhibits the Mig1/Mig2 repressors causing CSR2 derepression. Csr2 is constitutively ubiquitylated by Rsp5 on a conserved lysine, and ubiquitin chain elongation is counteracted by Ubp2. Right: Upon addition of glucose to the medium, Mig1/Mig2 repress CSR2 transcription. This is accompanied by an increased, phospho-dependent association of Csr2 with the Bmh1/2 proteins (14-3-3), along with its deubiquitylation, which requires protein kinase A. Note that Csr2 is also subject to proteasomal degradation (not depicted).

The mutation of some of the phosphorylated Ser/Thr residues located in this region into alanine (see Materials and methods) recapitulated the Csr2Δ150 mutation, because the Csr2-S/T-A mutant was still functional for endocytosis (Fig. S5, C and D) but was no longer deubiquitylated after glucose treatment (Fig. 10 C). This suggests that the glucose-induced deubiquitylation of Csr2 is an active process that involves the phosphorylation of its N-terminal Ser/Thr residues.

PKA activity regulates the glucose-mediated deubiquitylation of Csr2

To identify the potential kinase involved in this regulation, we screened 23 mutants from the deletion collection library on the basis of previous data that predicted kinases that may phosphorylate Csr2 (Mok et al., 2010; Fig. S5 E). Both Tpk1 and Tpk3, which are two of the three alternative catalytic subunits of yeast PKA, were also predicted to phosphorylate Csr2, but because of the described redundancy between these proteins (Broach, 2012), they were not included in this analysis. Instead, we studied the effect of the deletion of the PKA regulatory subunit, which is encoded by a single gene, BCY1 (Toda et al., 1987).

The deletion mutants were transformed with a plasmid encoding Csr2-TAP, and its migration pattern was evaluated by Western blotting before and after glucose addition in each strain. Csr2 displayed an unusual migration pattern in the bcy1Δ strain, because it migrated as a single band rather than a doublet (Fig. S5 E and Fig. 10 D). Because Bcy1 inhibits PKA activity, the sustained PKA activity in the bcy1Δ mutant might cause a constitutive deubiquitylation of Csr2, even in lactate medium. Accordingly, mutations of the N-terminal Ser/Thr residues, or deletion of this region (Δ150), restored a normal, ubiquitylated pattern of Csr2 in the bcy1Δ strain (Fig. 10 D and Fig. S5 F). This suggests that the PKA-mediated phosphorylation of the N-terminal part of Csr2 may regulate ubiquitylation. This was confirmed by using a PKA mutant (pkaas) in which the TPK1, TPK2, and TPK3 genes were replaced by their corresponding ATP-analogue sensitive mutant alleles (Zaman et al., 2009). The chemical inhibition of PKA in this strain using the ATP analogue 1NM-PP1 revealed that Csr2 was no longer deubiquitylated upon glucose replenishment (Fig. 10 E). Of note, the addition of glucose to cells grown in nonfermentable carbon sources was previously reported to induce a spike in cyclic AMP, in line with an activation of PKA in these conditions (Kraakman et al., 1999). This is further supported by the observation that Msn2-GFP, a transcription factor whose nuclear/cytosolic partitioning is regulated by PKA, relocates to the cytosol during the lactate/glucose transition (Fig. S5 G). Altogether, these data reveal a novel role for PKA in controlling the glucose-induced deubiquitylation of Csr2.

Csr2 dynamically interacts with the 14-3-3 proteins Bmh1 and Bmh2

Previous work on ART proteins revealed that cross-talk between phosphorylation and ubiquitylation sometimes involves the yeast 14-3-3 proteins Bmh1 and Bmh2 (Becuwe et al., 2012b; Merhi and André, 2012). A proteomic study identified many ARTs among the Bmh1/2 interactants, including Csr2 (Kakiuchi et al., 2007). Moreover, Csr2 possesses a type I 14-3-3 binding site (consensus Rxx[pS/T]xP) at residue S103, which we found to be phosphorylated in vivo. Using coimmunoprecipitations, we found that Csr2 bound endogenous Bmh1 and Bmh2, especially after glucose treatment (Fig. 10 F). This interaction depended on the phosphorylated residues in Csr2 N terminus, because their mutation disrupted the interaction with Bmh1/2 (Fig. 10 F). Because these N-terminal residues are also involved in Csr2 deubiquitylation, we speculate that upon glucose treatment, an increased, phospho-dependent binding of Csr2 to 14-3-3 proteins could lead to Csr2 deubiquitylation and thus its inactivation. In support of this hypothesis, Rsp5 interacted with Csr2 regardless of the presence of glucose, showing that the loss of ubiquitylation of Csr2 in these conditions is not due to its lack of interaction with Rsp5.

Discussion

In this study, we discovered a role for the poorly characterized ART protein Csr2 in transporter endocytosis upon glucose deprivation. We reveal that Csr2 selectively regulates the endocytosis of medium- to high-affinity hexose transporters, namely, Hxt2, Hxt4, Hxt6, and Hxt7. Csr2 was previously involved in Hxt6 endocytosis in stress conditions, which may represent a separate function (Nikko and Pelham, 2009). Endocytosis of high- and low-affinity hexose transporters upon glucose limitation occurs with different kinetics and likely results from different physiological inputs. The endocytosis of Hxt1 and Hxt3 likely corresponds to the removal of transporters that, because of their low affinity for glucose, are not appropriate when glucose is scarce. This regulation involves the Ras/cAMP-PKA pathway (Snowdon et al., 2009; Snowdon and van der Merwe, 2012; Roy et al., 2014). Instead, we propose that the endocytosis of high-affinity hexose transporters is triggered when they lack substrates to transport. Our results demonstrate that Csr2 is central to the second strategy only. Overall, our findings bolster the idea that ARTs target a limited set of transporters in a given physiological situation.

Although a defect in hexose transporters endocytosis should not impair viability, failure to do so may slow down adaptation and decrease cell fitness. The clearance of inadequate transporters from the plasma membrane could facilitate the insertion of neosynthesized transporters, and their degradation could provide metabolic intermediates required to cope with glucose exhaustion (as described in the case of N starvation, in which transporter endocytosis and degradation provide nitrogen to allow the onset of autophagy; Müller et al., 2015). This will be the focus of future studies. Finally, Hxt6 endocytosis also occurred in the context of yeast colony differentiation, suggesting that a Csr2-dependent hexose transporter remodeling occurs in this particular physiological condition.

We report the multiple levels at which Csr2 is regulated by glucose availability (see proposed working model in Fig. 10 G). Glucose represses CSR2 transcription through the yeast AMPK orthologue Snf1 and its downstream transcriptional repressors Mig1 and Mig2. Prior evidence from a high-throughput transcriptomics study suggested that the PP1 phosphatase (Glc7/Reg1), which counteracts Snf1 activity, negatively regulated CSR2 expression (Apweiler et al., 2012), in accordance with our observations. Thus, the transcriptional control of ART expression participates in the regulation of endocytosis. A glucose-independent, proteasome-mediated degradation of Csr2 superimposes on this transcriptional regulation but was independent of Rsp5, suggesting the involvement of another ubiquitin ligase in this mechanism and arguing against a preferential degradation of active Csr2 species. Because Csr2 is already deubiquitylated and presumably inactive, this degradation step is likely to be of minor significance for the regulation of endocytosis. However, it may be important for the homeostasis of ART proteins, which compete with one another for interaction with Rsp5.

Of note, the transcriptional induction of CSR2 in glucose-starvation conditions was not sufficient to trigger Hxt6 endocytosis. Numerous studies have pointed to a role of substrate binding and/or transport in regulating transporter trafficking (Blondel et al., 2004; Jensen et al., 2009; Cain and Kaiser, 2011; Keener and Babst, 2013; Ghaddar et al., 2014; Roy et al., 2015). Although the nature of the signal that sets off high-affinity glucose transporter endocytosis in the absence of glucose will need to be further explored, hexose binding and/or transport could behave as a protective signal against high-affinity glucose transporter endocytosis.

An additional glucose-mediated regulation of Csr2 occurred at the posttranslational level. Csr2 ubiquitylation at a conserved site in the arrestin-C domain was required for its function in endocytosis. Proteomic database searches revealed that this residue is the major ubiquitylation site for nearly all ART proteins (Craig et al., 2004). Although the mechanism by which ART ubiquitylation regulates their function remains to be investigated, we reveal for the first time, using BiFC, that it is not essential for cargo interaction. Moreover, we found that Csr2 was deubiquitylated upon glucose addition to the medium, likely causing its inactivation (Fig. 10 G), at a time when endocytosis is relayed by the glucose-activated ART protein Rod1 (Nikko and Pelham, 2009; Becuwe et al., 2012b; Llopis-Torregrosa et al., 2016). It is interesting to note that Rsp5 still interacted with Csr2 after glucose addition (i.e., when Csr2 is no longer ubiquitylated), supporting the idea of an active deubiquitylation event. However, the enzyme involved could not be identified at this stage. Functional redundancies and overlaps within ubiquitin isopeptidases can compromise the identification of their function by genetic approaches (Amerik et al., 2000; Kouranti et al., 2010; Weinberg and Drubin, 2014).

The glucose-induced deubiquitylation of Csr2 required its N-terminal region, particularly Ser/Thr residues that we identified as phosphorylated. PKA appeared as a negative regulator of Csr2 ubiquitylation, and this depended on the integrity of Csr2 phospho-residues. These data, together with an apparent activation of PKA during the lactate/glucose shift, lead us to suggest that PKA may directly phosphorylate residues in the N-terminal region of Csr2 in these conditions, thereby participating to the deubiquitylation/inactivation process. However, this remains to be formally proved.

A dynamic interaction of ARTs with the 14-3-3 proteins Bmh1/Bmh2 was previously implicated in the regulation of ART ubiquitylation (Becuwe et al., 2012b; Merhi and André, 2012). In these studies, 14-3-3 proteins were proposed to hinder ART ubiquitylation by Rsp5, and thus to keep them in an inactive state, until the interaction is released. Strikingly, we report here the reversal of this mechanism, in which Bmh1/Bmh2 binding to the N-terminal phosphorylated residues of Csr2 is concomitant to Csr2 deubiquitylation. A unifying model could be that 14-3-3 binding leads to a constitutive deubiquitylation of ART proteins, maybe by favoring the recruitment of deubiquitylating enzymes. This will be the subject of future investigations. Yet our results consolidate the paradigm of a nutrient-regulated phosphorylation/ubiquitylation crosstalk on ART proteins in the control of transporter endocytosis.

Our study completes previous work on the involvement of the yeast AMPK orthologue, Snf1, in carbon source transporters homeostasis (Becuwe et al., 2012b; O’Donnell et al., 2015). The Snf1/PP1 nexus channels glucose presence or absence signals through various ART proteins so that cells efficiently adapt to glucose fluctuations. Additionally, the contribution of PKA activity in Csr2 inactivation by glucose also reveals an unprecedented cross-talk of these two signaling pathways in the regulation of endocytosis.

Although the regulation of nutrient transporter endocytosis by extracellular nutrients remains marginally studied in mammalian cells, GLUT1 availability at the cell surface is regulated by glucose starvation via AMPK and the arrestin-related protein TXNIP (Wu et al., 2013). This striking conservation reveals that similar regulatory mechanisms are at stake in the regulation of transporter endocytosis in mammalian cells. These results have important consequences when addressing the molecular basis of several pathologies. TXNIP is an important metabolic regulator, particularly of glucose and lipid metabolism (Parikh et al., 2007; Patwari and Lee, 2012; Shen et al., 2015; Dotimas et al., 2016). TXNIP acts as a tumor suppressor in a mouse model of thyroid cancer: its overexpression causes a reduction of cellular glucose influx and impairs cell migration (Morrison et al., 2014), whereas TXNIP deficiency is linked to the appearance of hepatocellular carcinomas (Sheth et al., 2006). Another arrestin-related protein, ARRDC3, is linked to obesity in mice and humans (Patwari et al., 2011; Patwari and Lee, 2012) and, through its role in the endocytosis of β4 integrin, also acts as a tumor suppressor (Draheim et al., 2010). Thus, future studies should focus on reaching a better understanding of the function and the regulation of arrestin-related protein by metabolism to form the basis of new therapeutic approaches.

Materials and methods

Yeast strains, transformation, and growth conditions

Strains are listed and detailed in Tables S1 and S2. All strains are derivatives of the BY4741/2 strains unless otherwise indicated. The 9-arrestinΔ mutant was provided by H. Pelham (Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge, England, UK; Nikko and Pelham, 2009). Yeast was transformed by standard lithium acetate/polyethylene glycol procedure. Gene deletion and tagging were performed by homologous recombination and confirmed by PCR on genomic DNA. This was critical because several HXT genes display a strong sequence homology at the DNA level, which sometimes leads to mistargeting of the tagging cassette. Throughout this study, transporters were tagged at the chromosomal locus by homologous recombination, and their expression was driven by their endogenous promoter.

The csr2-1 mutant was generated by inserting a KanMax cassette preceded by a stop codon at +45 bp relative to the CSR2 start codon. This was necessary because in the csr2Δ strain, several HXTs showed an aberrant expression level that could not be linked to CSR2 function (Fig. S1).

Cells were grown in yeast extract/peptone/glucose–rich medium or in synthetic complete (SC) medium (yeast nitrogen base 1.7 g/liter [MP Biomedicals], ammonium sulfate 5 g/liter [Sigma-Aldrich], and dropout amino acid solutions [Elis Solutions]) containing 2% (wt/vol) glucose or 0.5% (vol/vol) sodium-lactate, pH 5.0 (Sigma-Aldrich). For the growth protocol, cells were routinely grown overnight in SC-glucose medium (inoculation at absorbance at 600 nm [A600] = 0.001 in the evening), harvested in early exponential phase in the morning (A600 = 0.3–0.5), resuspended in the same volume of SC medium containing 0.5% lactate (vol/vol), 2% raffinose (wt/vol), or water (no carbon source) as indicated and grown for the indicated times. For Csr2 deubiquitylation analysis (Fig. 9, A and B), 2% glucose (or the indicated sugar at the indicated concentration) was added back to cells grown in SC-lactate medium. 2-Deoxyglucose and 3-O-methylglucose were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and were used at final concentrations of 0.2% and 2%, respectively.

Plasmids and constructs

The plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S3.

To obtain pSL168, the promoter region of CSR2 (912 bp) was amplified from genomic DNA (using oligonucleotides oSL437/oSL438) and cloned BamHI–EcoRI upstream the lacZ gene into a Yep358-based vector (Lodi et al., 2002) to replace the JEN1 promoter.

The plasmid encoding untagged CSR2 was constructed by amplifying the CSR2 gene (−500 bp before ATG, +300 bp after stop codon) from genomic DNA using primers oSL713/oSL714 and cloning at XhoI–XbaI sites into pRS416. To obtain pSL324, a region containing the ECM21 promoter (−500 bp) and ORF was amplified from genomic DNA (using oligonucleotides oSL770/oSL751) and cloned SpeI–XhoI into pSL94 (Becuwe et al., 2012b) at SpeI–XhoI sites.

The plasmid encoding HA-tagged Csr2 under the control of its endogenous promoter (pSL308) was constructed using a 1-kb promoter region of CSR2 (from pSL172, a pRS416-based plasmid containing pCSR2:GFP-CSR2) cloned at SacI–XbaI sites in place of the ADH promoter into pSL178 (pADH:CSR2-3HA).

The K670R mutation in CSR2 was obtained by site directed mutagenesis on pSL172 using oligonucleotides oSL715/oSL716, giving pSL314. The NheI–SalI fragment from pSL314 (containing the KR mutation) was then cloned into pSL308 at NheI–SalI sites, giving pSL318.

The PYm mutations in CSR2 were obtained in two steps. A PCR product (oSL448/oSL656 using pSL172 as a template) was digested at BstEII–SalI and cloned at BstEII–XhoI sites in pSL172 to mutate the C-terminal PPRY motif of Csr2 (residues 1113–1116) into PPRA, giving pSL306. This was then mutagenized using oSL662/oSL663 to mutate the LPPY site (residues 793–796) into LPPA, giving pSL307. The XbaI–SmaI fragment from pSL307 (containing the mutations) was then cloned into pSL311 (a pRS415-based plasmid containing pCSR2:mcs-3HA).

For the N-terminal truncation (Δ150), plasmid pSL325 was generated by amplifying a truncated version of CSR2 (missing the first 450 nucleotides; oSL768/oSL440) from pSL308 and cloning XbaI–XhoI into pSL308-digested XbaI–XhoI to replace WT CSR2. Plasmid pSL345 was generated using a similar strategy: a truncated version of CSR2-KR (missing the first 450 nucleotides) was amplified (oSL768/oSL440) from pSL318 and was cloned at XbaI–XhoI into pSL308-digested XbaI–XhoI to replace WT CSR2.

For the Ser–Thr mutations, a mutant version of CSR2 was obtained by gene synthesis (MWG Eurofins; pSL350), digested at PstI–PstI, and cloned PstI–PstI at endogenous CSR2 sites into pSL308, giving pSL351. The Ser/Thr sites mutated included some of those identified by mass spectrometry (underlined in the following text), and neighboring sites (≤2 residues in Nt or Ct of the modified residue) when present: S42T43S44S46, S59S60S61, T72S75T77S78S79, S103, T116S118, S127, S148. All residues were mutated into alanine. The construct was expressed and functional for endocytosis, as shown in Fig. 10 and Fig. S5, C and D.

All constructs were checked by sequencing. The pCSR2-CSR2-TAP WT and pCSR2-CSR2(S/T-A)-TAP plasmids were obtained by digestion of pSL308 and pSL351, respectively, with the restriction enzyme XhoI and by cotransformation and homologous recombination in yeast using a PCR product amplified from strain ySL1741 (in which Csr2 is endogenously tagged with a TAP cassette) using primers oSL806/oSL807, so that the C-terminal 3HA tag is replaced by the TAP cassette. Clones were rescued in bacteria and named pSL386 (pCSR2-CSR2-TAP) and pSL387 (pCSR2-CSR2(S/T-A)-TAP).

The sequences of the primers used in this study are provided in Table S4.

Total protein extracts

Trichloroacetic acid (TCA; Sigma-Aldrich) was added directly to the culture to a final concentration of 10% (vol/vol) and incubated on ice for 10 min. Cells were then harvested by centrifugation for 1 min at room temperature at 16,000 g, then lysed with glass beads in 100 µl of TCA (10% vol/vol) for 10 min at 4°C. Beads were removed, the lysate was centrifuged for 1 min at room temperature at 16,000 g, and the resulting pellet was resuspended in a modified sample buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 100 mM DTT, 2% SDS, 0.1% bromophenol blue, and 10% glycerol, containing an additional 200 mM of unbuffered Tris solution) at a concentration of 50 µl/initial OD unit, before being denatured at 37°C for 10 min; 10 µl was loaded on SDS-PAGE gels.

MG-132, cycloheximide, and 1NM-PP1 treatment

For MG-132 treatment, cells (pdr5Δ background) were treated with 10 µM MG-132 (Sigma-Aldrich) 30 min before glucose addition in the medium. For cycloheximide treatment, cells were treated with 100 µg/ml of cycloheximide (Sigma-Aldrich) for the indicated times.

For 1NM-PP1 treatment of the pkaas mutant strain (tpk1M164G tpk2M147G tpk3M165G) and its WT control (strains Y3561 and Y2864, respectively, provided by J. Broach, Penn State University, Hershey, PA; Zaman et al., 2009), cells were harvested and transferred into SC medium containing 0.5% lactate and treated for 4 h with either 50 µm 1NM-PP1 (1-[1,1-dimethylethyl]-3-[1-naphthalenylmethyl]-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4-amine; Cayman Chemical) or an equivalent volume of DMSO.

Antibodies, immunoblotting, quantifications, and statistical analysis

We used mouse monoclonal antibodies against GFP (clones 7.1 and 13.1; 11814460001; Roche), HA (clone F7; sc-7392; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), anti-ubiquitin coupled to horseradish peroxidase (clone P4D1; sc-8017; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) and rabbit polyclonal antibodies against 3-phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK; NE130/7S; Nordic-MUbio), Nedd4 (ab14592; Abcam), Bmh2 (a gift from S. Lemmon, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL; Gelperin et al., 1995). Luminescence signals were acquired with the LAS-4000 imaging system (Fujifilm). Quantifications were performed using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health) on nonsaturated blots from independent experiments (n ≥ 3). The ratio of the free GFP signal over the total GFP signal in any given lane was calculated. A two-sided t test was performed and the p-values are indicated (NS, P > 0.05; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

Fluorescence microscopy

Cells were mounted in the appropriate culture medium and imaged at room temperature with a motorized BX-61 fluorescence microscope (Olympus) equipped with a PlanApo 100× oil-immersion objective (1.40 NA; Olympus), a QiClick cooled monochrome camera (QImaging), and the MetaVue acquisition software (Molecular Devices). GFP-tagged proteins were visualized using a GFP filter set (41020; Chroma Technology Corp.; excitation HQ480/20×, dichroic Q505LP, emission HQ535/50m). For FM4-64 labeling, FM4-64 (Invitrogen) was added to 1 ml culture (10 µM final) and incubated at 30°C in a thermomixer for 15 min. Cells were then washed once with 1 ml medium. FM4-64 signal was visualized using an HcRedI filter set (41043; Chroma Technology Corp.; excitation HQ575/50×, dichroic Q610lp, emission HQ640/50m). For CMAC (7-amino-4-chloromethylcoumarin) labeling, cells were incubated with 100 µM CMAC (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 10 min under agitation at 30°C, then washed twice with 1 ml of medium. CMAC signal was visualized using a DAPI filter set (31013v2; Chroma Technology Corp.; excitation D365/10×, dichroic 400dclp, emission D460/50m). Images were processed in ImageJ for levels and for contrast when indicated.

BiFC

Hxt6 was tagged with VC at its chromosomal locus, as previously described, using pFA6a-VC-kanMX6 (Sung and Huh, 2007). Csr2 was tagged with VN at its chromosomal locus, as previously described, using pFA6a-VN-His3MX6 (Sung and Huh, 2007; giving ySL1787), but no BiFC signal was observed, because of the low expression level of Csr2. Thus, plasmids expressing pTEF-driven Csr2-VN and derivatives were constructed as follows. Csr2-VN was PCR-amplified from genomic DNA prepared from strain ySL1787 using oSL1007/oSL1008, digested XbaI–XhoI, and cloned XbaI–XhoI in pRS415-TEF (Mumberg et al., 1995), giving pSL391 (pTEF:Csr2-VN). Csr2-KR-VN was constructed by cloning of a SalI–NheI fragment (containing the KR mutation) originating from pSL314 (see Plasmids and constructs section) into pSL391, giving pSL393 (pTEF:Csr2-KR-VN). For the negative control, VN was PCR-amplified from pFA6a-VN-His3MX6 and cloned at BamHI–EcoRV sites in pRS415 (giving pSL394). The pTEF promoter was excised from pRS415-TEF with SacI–BamHI and cloned at SacI–BamHI sites into pSL394, giving pSL392 (pTEF:-Ø-VN). BiFC signals were visualized using a GFP filter set (41020 from Chroma Technology Corp.; excitation HQ480/20×, dichroic Q505LP, emission HQ535/50m).

Two-photon confocal microscopy

Two-photon confocal microscopy (Fig. 2) was performed according to Váchová et al. (2009). In brief, colonies were grown for 4 d at 28°C on glycerol-ethanol complete respiratory medium (1% yeast extract, 3% glycerol, 1% ethanol, 2% agar, and 10 mM CaCl2) medium, embedded in low-gelling agarose directly on the plates, and then cut vertically down the middle. They were placed on the coverslip (the cutting edge to the glass), and the colony side views of GFP fluorescence were obtained by two-photon confocal microscopy. Images were acquired with a true confocal scanner microscope (SP8 AOBS WLL MP; Leica Biosystems) fitted with a mode-locked laser (Ti:Sapphire Chameleon Ultra I; Coherent) for two-photon excitation and using 20×/0.70 and 63×/1.20 water immersion plan apochromat objectives. Excitation wavelengths of 920 nm were used, with emission bandwidths set to 480–595 nm. Images of whole colonies and central parts of the colonies were composed of two stitched fields of view.

β-galactosidase assays

For β-galactosidase assays, cells carrying pCSR2-lacZ plasmid (pSL168) were grown overnight in SC-based glucose medium to exponential phase. The A600 of each culture was measured and, for each assay, 1 ml of cells were harvested by centrifugation. The remaining cells were resuspended in SC-based lactate medium and grown for 2 h before the next assay. For each assay, cell pellets were frozen in liquid nitrogen and resuspended in 800 µl buffer Z (50 mM NaH2PO4, 45 mM Na2HPO4, 10 mM KCl, and 10 mM MgSO4, pH 7) to which β-mercaptoethanol was added (27 µl/10 ml; Sigma-Aldrich). Then, 160 µl ortho-nitrophenyl-β-galactoside at 4 mg/ml (Sigma-Aldrich) were added, and samples were incubated at 37°C for 30 min, which was still in the linear phase of the reaction. The reactions were stopped by adding 400 µl 1 M Na2CO3. The samples were then centrifuged for 2 min at 14,000 rpm to remove cell debris, and absorbance at 420 nm (A420) was measured. To remove background in each experiment, assays were performed similarly using cells that did not express the lacZ reporter gene. β-Galactosidase activities were calculated as 1,000 × [A420/(A600 × time)], where A420 is the mean of three technical replicates. For each experiment, histograms show the result and standard error of at least three independent biological replicates.

Quantitative RT-PCR

For quantitative RT-PCR, cells were grown overnight in glucose-containing SC medium and then switched into SC-lactate medium for 2 h. For each sample, total RNA extractions were performed from 10 OD units of cells, using the Nucleospin RNA II extraction kit (MACHEREY-NAGEL). Reverse transcription reactions were performed using random hexamer primers (GE Healthcare; final concentration 0.25 µg/µl) and Invitrogen SuperScript II reverse transcription. cDNA quantification was achieved through quantitative RT-PCR using a LightCycler 480 (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. CSR2 cDNAs were amplified using oSL685/oSL686 primers, and data were normalized to ACT1 transcripts (oligonucleotides oSL704/oSL705). The sequences of the primers used in this study are provided in Table S4.

Purification of His6-tagged ubiquitylated conjugates

The purification of all cellular ubiquitylated conjugates for the ubiquitylome experiments were performed from WT BY4741 cells transformed with a plasmid encoding a pCUP1-driven His6-tagged ubiquitin (Gwizdek et al., 2006), provided by C. Dargemont (Hôpital St. Louis - Institut Universitaire d’Hématologie, Paris, France). These purifications were performed four times from four independent cultures. Cells were grown overnight in SC-based lactate medium to exponential phase (A600 = 0.3) without the addition of exogenous copper in the medium, to avoid His6-tagged ubiquitin overexpression. In each replicate, 50 OD units of cells were harvested, and glucose (2% final) was added to the remaining cells. The remaining 50 OD units of cells were harvested after 10 min of glucose treatment. Several proteins, such as transcription factors or metabolic enzymes, are rapidly ubiquitylated and degraded by the proteasome in response to glucose (Spielewoy et al., 2004; Gancedo, 2008; Santt et al., 2008). To identify proteins that display other, nondegradative types of ubiquitylation, such as monoubiquitylation or K63-linked ubiquitylation, we chose not to inhibit proteasomal degradation, which would favor the identification of K48-linked ubiquitin chains (Xu et al., 2009). Thus, glucose treatment was performed without MG-132. The purification of His6-tagged ubiquitin conjugates was then performed using immobilized metal affinity chromatography as described later, following a protocol adapted from Ziv et al. (2011) and modified by Becuwe et al. (2012b). Cells were precipitated with TCA (10% final concentration) for 30 min on ice and lysed with glass beads for 20 min at 4°C. After centrifugation, the pellet was resuspended with 500 µl guanidinium buffer (6 M GuHCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 100 mM K2HPO4, 10 mM imidazole, 100 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Triton X-100) and incubated for 1 h at room temperature on a rotating platform. After centrifugation (16,000 g, 10 min at room temperature), the lysate was incubated for 2.5 h with nickel-nitriloacetic acid beads (Ni-NTA Superflow; QIAGEN). The beads were then washed three times with guanidinium buffer, three times with wash buffer 1 (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM K2HPO4, 20 mM imidazole, 100 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Triton X-100), and three times with wash buffer 2 (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM K2HPO4, 10 mM imidazole, 1 M NaCl, and 0.1% Triton X-100). His6-ubiquitin-conjugated proteins were finally eluted with 40 µl elution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and 250 mM imidazole) for 10 min at room temperature.

For the purification of ubiquitylated species of Hxt6, vrp1Δ and vrp1Δcsr2-1 cells expressing endogenously tagged Hxt6-GFP were transformed with the pCUP1-driven His6-tagged ubiquitin construct described in the preceding paragraph. Cells were grown overnight in SC-based glucose medium to exponential phase (A600 = 0.3), resuspended in SC-based lactate medium to which 100 µM CuSO4 was added, and grown for 6 h at 30°C. Cell pellets (50 OD units) were frozen at −80°C. Cells were then precipitated with TCA (10% final concentration) for 30 min on ice and lysed with glass beads for 10 min at 4°C. Cell lysates were centrifuged for 1 min at room temperature at 16,000 g, and the resulting pellet was resuspended in a modified sample buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 100 mM DTT, 2% SDS, 0.1% bromophenol blue, and 10% glycerol, containing an additional 200 mM of unbuffered Tris solution) at a concentration of 10 initial OD units/50 µl. Samples were then diluted 20 times in guanidinium buffer (6 M GuHCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 100 mM K2HPO4, 10 mM imidazole, 100 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Triton X-100) and incubated for 2 h with nickel-nitriloacetic acid beads (Ni-NTA Superflow) at room temperature on a rotating platform. The beads were then washed three times with guanidinium buffer, three times with wash buffer 1 (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM K2HPO4, 20 mM imidazole, 100 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Triton X-100), and three times with wash buffer 2 (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM K2HPO4, 10 mM imidazole, 1 M NaCl, and 0.1% Triton X-100). His6-ubiquitin-conjugated proteins were finally eluted with 100 µl elution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and 250 mM imidazole) for 10 min at room temperature.

Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry acquisition

Proteins were digested overnight at 37°C in 20 µl 25 mM NH4HCO3 containing sequencing-grade trypsin (12.5 µg/ml; Promega). The resulting peptides were sequentially extracted with 70% acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid. Digested samples were acidified with 0.1% formic acid. All digests were analyzed by a LTQ Velos Orbitrap (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with an EASY-Spray nanoelectrospray ion source (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled to an Easy nano-LC Proxeon 1000 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Chromatographic separation of peptides was performed with the following parameters: Acclaim PepMap100 C18 precolumn (2 cm, 75 µm inside diameter, 3 µm, 100 Å), Pepmap-RSLC Proxeon C18 column (50 cm, 75 µm inside diameter, 2 µm, 100 Å), 300 nl/min flow, using a gradient rising from 95% solvent A (water, 0.1% formic acid) to 35% B (100% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid) in 107 min, followed by a column regeneration of 13 min, for a total run of 2 h. Peptides were analyzed in the Orbitrap in full-ion scan mode at a resolution of 30,000 (at m/z 400) and with a mass range of m/z 400–1,800. Fragments were obtained with a collision-induced dissociation activation with a collisional energy of 40%, an isolation width of 2 D, and an activation Q of 0.250 for 10 ms. Tandem mass spectrometry data were acquired in the linear ion trap in a data-dependent mode, in which the 20 most intense precursor ions were fragmented, with a dynamic exclusion of 20 s, an exclusion list size of 500, and a repeat duration of 30 s.

Raw mass spectrometry data from the LTQ Velos Orbitrap were analyzed with MaxQuant (Cox and Mann, 2008) version 1.5.2.8, using the Andromeda peptide search engine (Cox et al., 2011). Quantifications were performed with MaxLFQ (Cox et al., 2014) using the proteins identified with at least two peptides and analyzed with Perseus software version 1.5.0.15. For the statistical analysis of ubiquitylome experiments, four replicates of each condition (glucose and lactate) were separated into two statistical groups, and a Student’s t test was performed on both groups with a randomization number of 250 to determine the protein enrichments between the groups. The results are displayed as a volcano plot (Hubner and Mann, 2011); the black curves were plotted using a false discovery rate of 0.05 and S0 = 0.2 to highlight the candidates that were significantly enriched in each condition, respectively.

Csr2-3HA purification for the mapping of phosphorylation and ubiquitylation sites by mass spectrometry