Abstract

Adaptive thermogenesis regulates core body temperature, controls fat deposition, and contributes strongly to the overall energy balance. This process occurs in brown fat and requires uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1), an integral protein of the inner mitochondrial membrane. Classic biochemical studies revealed the general principle of adaptive thermogenesis: in the presence of long-chain fatty acids (FA), UCP1 increases the permeability of the inner mitochondrial membrane for H+, which makes brown fat mitochondria produce heat rather than ATP. However, the exact mechanism by which UCP1 increases the membrane H+ conductance in a FA-dependent manner has remained a fundamental unresolved question.

Recently, the patch-clamp technique was successfully applied to the inner mitochondrial membrane of brown fat to directly characterize the H+ currents carried by UCP1. Based on the patch-clamp data, a new model of UCP1 operation was proposed. In brief, FA anions are transport substrates of UCP1, and UCP1 operates as an unusual FA anion/H+ symporter. Interestingly, in contrast to short-chain FA anions, long-chain FA anions cannot easily dissociate from UCP1 due to strong hydrophobic interactions established by their carbon tails, and a single long-chain FA participates in many H+ transport cycles. Therefore, in the presence of long-chain FA, endogenous activators of brown fat thermogenesis, UCP1 effectively operates as an H+ uniport. In addition to their transport function, long-chain FA competitively remove tonic inhibition of UCP1 by cytosolic purine nucleotides, thus enabling activation of the thermogenic H+ leak through UCP1 under physiological conditions.

1. Introduction

In humans and other mammals, the core body temperature is maintained at around 37°C, which is well above normally encountered ambient temperatures in most climates. The heat required to support such a high body temperature is produced by numerous exothermic reactions within the body. These reactions often are not specialized thermogenic reactions, have other primary physiological functions, and cannot be regulated to control the amount of heat produced. The body appears to have only a few adjustable thermogenic reactions that exist specifically for heat production and constitute “adaptive thermogenesis”. The H+ leak across the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) of brown fat is primarily responsible for adaptive thermogenesis. This leak dissipates an electrochemical H+ gradient (ΔΨ) across the IMM and converts ΔΨ into heat at the expense of mitochondrial ATP production. The mitochondrial H+ leak in brown fat is mediated by uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) [1–6], which belongs to the SLC25 superfamily of mitochondrial solute carriers[7].

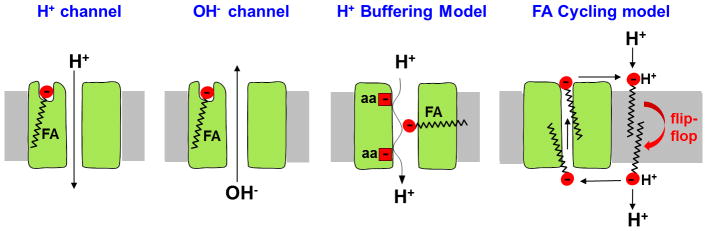

There are two major regulators of the thermogenic H+ leak via UCP1: free long-chain fatty acids (FA) and purine nucleotides. FA activate the UCP1-dependent H+ leak, whereas Mg2+-free cytosolic purine nucleotides (primarily ATP) inhibit it. Despite the fact that FA and purine nucleotides were established as the principal UCP1 regulators as early as the 1970s [8, 9], the exact mechanism involved is still actively debated. Several mechanisms of the FA-dependent H+ leak through UCP1 have been proposed. Over the years, the following models have been most widely discussed (Fig. 1): 1) a H+ channel activated by allosteric binding of long-chain FAs. In this model it has often been suggested that UCP1 has a basal, FA-independent H+ transport activity and FA are primarily required to competitively remove purine nucleotide inhibition [10–14]; 2) an OH− channel activated by allosteric binding of FA [15, 16]; 3) the “proton buffering” model in which UCP1 is a H+ channel where FAs bind in the pore and their carboxylic acid groups complete the H+ translocation pathway along with titratable amino acid residues of UCP1 [17]; and 4) the “FA cycling” model in which UCP1 is a long-chain FA anion carrier that transports H+ indirectly: UCP1 carries long-chain FA anions outside the mitochondria where they bind a proton and, in protonated form, “flip-flop” back across the IMM to release the proton into the mitochondrial matrix [18]. These models have not been reconciled, and numerous questions remain about the mechanism of the UCP1-mediated H+ leak. First, what species are translocated by UCP1? Second, does UCP1 have a FA-independent “basal” H+ transport activity? Third, what is the mechanism by which FA increase H+ leak through UCP1? And finally, how do FA overcome purine nucleotide inhibition?

Figure 1. Proposed models of UCP1 operation.

H+ channel activated by allosteric binding of FA, OH− channel activated by allosteric binding of FA, “H+ buffering” model, and “FA cycling” model are shown.

Arguably, the main roadblock to understanding the mechanism of the UCP1-mediated H+ leak has been the lack of direct methods to measure this leak and the inability to rigorously control experimental conditions. The patch-clamp technique resolved these experimental limitations for the first time and allowed high-resolution functional analysis of UCP1 in its native membrane environment [19]. This method has facilitated the gathering of a wealth of new experimental data regarding UCP1, leading to a refined model explaining the mechanism by which FA and purine nucleotides regulate the H+ leak through UCP1. Here we summarize the data obtained by the patch-clamp analysis of UCP1 and discuss how the new model of UCP1 operation correlates with recently obtained structural data for UCP1 and other SLC25 members.

2. Patch-clamp recording of UCP1 currents

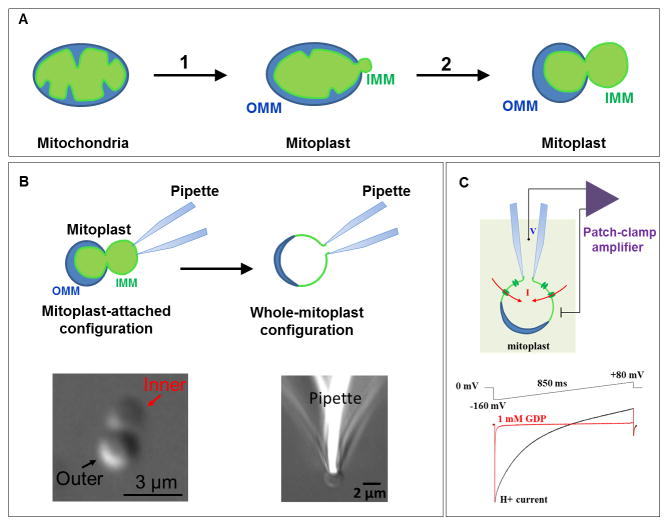

UCP1-dependent H+ currents were recorded from the vesicles of the whole IMM (so called mitoplasts) isolated from brown fat of mice. Each mitoplast represents an intact IMM of a single mitochondrion (Fig. 2A and B). The patch-clamp technique is applied to mitoplasts in essentially the same way as it is to cells, but the size of a mitoplast is significantly smaller. After formation of the initial gigaohm seal between the patch pipette and a mitoplast, we disrupt the small portion of the IMM under the pipette (break-in into the mitoplast) by application of high-amplitude voltage steps to gain access into the mitochondrial matrix from the pipette (Fig. 2B). In this configuration, called the whole-mitoplast or whole-IMM configuration, currents flowing across the whole IMM can be measured and full control of the voltage can be achieved using two electrodes – one in the pipette and one in the bath solution (Fig. 2B and C). In addition, solution composition is controlled on both sides of the IMM, matrix (pipette) and cytosolic (bath).

Figure 2. Mitochondrial patch-clamp.

(A) Preparation of mitoplasts (vesicles of the whole IMM): (1) Mitochondria isolated from tissue lysate are subjected to low-pressure French press to rupture the OMM and release the IMM (mitoplasts are formed); (2) when mitoplasts are incubated in a KCl solution, the IMM is further released from the OMM and mitoplasts assume an 8-shaped form. Remnants of the OMM are attached to the IMM. (B) Formation of the gigaom seal between the glass patch pipette and the IMM (mitoplast attached configuration) is followed by break-in into the mitoplast to achieve a whole-mitoplast configuration for recording currents across the whole IMM. The IMM patch under the pipette is destroyed by high-amplitude voltage pulses (200–500 mV). After break in, the IMM is completely released from the OMM, and mitoplast assumes a round shape. An isolated 8-shaped mitoplast and a round mitoplast attached to the pipette after break-in are shown in the lower panel. (C) Patch-clamp recording from the whole IMM. FA-dependent H+ current via UCP1 before (black) and after (red) application of UCP1 inhibitor GDP into the bath. The voltage protocol used to induce the current is shown above the current traces. All voltages indicated are within the mitochondrial matrix in respect to the bath (cytosol).

In the whole-IMM configuration, long-chain FA induce a large H+ current across the IMM of brown fat [19] (Fig. 2C). This current is specific to brown fat, can be inhibited by purine nucleotides such as GDP and ATP, and cannot be detected in UCP1-deficient mice. The H+ selectivity of the currents induced by long-chain FA was established by measuring reversal potentials of the UCP1 current and comparing them to the theoretical Nernst equilibrium potentials [19]. These experiments demonstrated the possibility of recording UCP1 currents directly using the patch-clamp technique. For a carrier, UCP1 produces currents of enormous amplitude (despite of the fact that carriers have at least three orders of magnitude lower unitary currents as compared to ion channels) [20]. The extremely high density of UCP1 expression in brown fat (~10% of the total mitochondrial protein) can explain the large currents recorded.

3. FA are required for the UCP1-dependent H+ leak

Despite the general consensus that FA increase the UCP1-dependent H+ leak, it is controversial whether FA are required for UCP1 activation or UCP1 have basal, FA-independent H+ transport activity. UCP1 reconstituted in artificial lipid membranes requires FA for its activity [21], whereas native UCP1 in intact isolated brown fat mitochondria appears to stay active even in the presence of high concentrations of the FA acceptor bovine serum albumin [15]. It is not clear whether reconstituted UCP1 behaves in exactly the same way as UCP1 in its native membrane environment. On the other hand, in the experiments with intact mitochondria, FA could not be completely removed from the mitochondrial membranes even by high concentrations of albumin. Mitochondria of various tissues such as heart (55), brain (56), liver (57), kidney (58), and skeletal muscle (59), contain phospholipase A2 (PLA2), and FA generated by such continuous PLA2 activity would be difficult to remove completely from mitochondrial suspensions.

The patch-clamp technique not only studies UCP1 in its native membrane environment but also provides adequate control over the concentration of membrane FA. The cytosolic and matrix faces of the IMM are exposed to almost infinite amounts of bath and pipette solutions, and there is constant perfusion/diffusion of solutions on both sides of the IMM. Such patch-clamp experiments have demonstrated that the IMM of brown fat indeed possesses a very robust PLA2 activity, and it is very effective in activating the H+ leak through UCP1 [19]. Furthermore, this PLA2 activity was so strong that application of FA-free albumin only on the cytosolic face of the IMM could not completely inhibit the H+ current via UCP1. In contrast, high concentrations of albumin or cyclodextrin (another FA acceptor) applied on both sides of the IMM fully inhibited the H+ current. These experiments demonstrate that UCP1 has no FA-independent basal H+ transport activity. Previous observations of such “basal activity” in suspensions of isolated mitochondria were very likely associated with the inability to fully extract endogenous FA due to mitochondrial PLA2 activity. These results also demonstrate that the signaling mechanisms associated with IMM phospholipases may play important roles in regulating UCP1 in vivo.

4. FA activate the H+ leak through UCP1 by serving as its transport substrates

To understand the mechanism by which FA activate the UCP1-dependent H+ leak, it is important to identify the ion species transported by UCP1. Various models proposed previously claimed that UCP1 conducts either H+ (or OH− in the opposite direction) or FA anions (Fig. 1), but an agreement regarding the ion species conducted by UCP1 has yet to be reached.

As mentioned previously, the patch-clamp experiments demonstrated that the UCP1 current induced by long-chain FA is highly H+ selective [19]. However, this experiment alone does not exclude a possibility that UCP1 transports FA anions. Indeed, in the FA-cycling model, although the transmembrane currents are carried by protons, only FA anions are directly transported by UCP1 (Fig. 1).

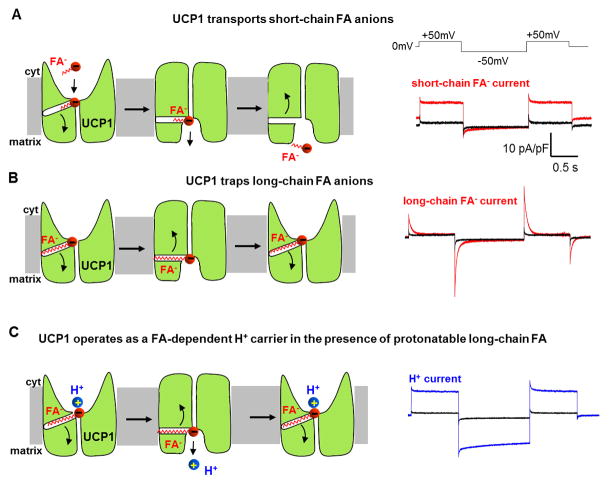

To reveal a possible FA anion current and isolate it from the H+ current, UCP1 activity was recorded in the presence of various low-pKa FA analogs that do not bind H+ at physiological pH and cannot cause UCP1-dependent H+ translocation. Such electrophysiological experiments demonstrated that UCP1 indeed transports low-pKa FA anions [19]. These experiments also discovered that long-chain and short-chain FA anions are handled by UCP1 in two different ways. Short-chain FA anions are simply transported by UCP1 across the membrane and produce steady transmembrane currents in response to a voltage step protocol (Fig. 3A). Long-chain FA anions are translocated but cannot dissociate from UCP1 due to strong hydrophobic interactions, resulting in limited motion within the membrane and transient currents in response to the same voltage step protocol (Fig. 3B). In addition, due to the higher hydrophobic interactions, long-chain FA anions activate UCP1 currents at significantly lower concentrations than short-chain FA (low micromolar vs. millimolar, respectively). In transport of FA, it is assumed that UCP1 is a carrier and similar to other SLC25 members UCP1 operates by alternating-access mechanism of transport [22–24]. Although certain aspects of UCP1 transport remind of the ion channel mechanism [19, 25], it is unlikely that efficient transport of FA anions (containing two opposite moieties, polar and hydrophobic) can be accomplished via a simple pore.

Figure 3. Model of UCP1 operation based on the electrophysiological data.

(A) Left panel: the mechanism of steady UCP1 current induced by short-chain low-pKa FA analogs added on the cytosolic face of the IMM. Short-chain FA are simply transported by UCP1 across the IMM. UCP1 has two conformation states, with substrate binding site exposed either to the cytosolic (c-state) or matrix (m-state) side of the IMM. To reflect the fact that long-chain FA anions cannot bind to UCP1 on the matrix side [19], the access to the substrate binding site in the m-state is shown narrower as compared to c-state. Right panel: an original trace of steady UCP1 current induced by short-chain low-pKa FA analogs. Voltage protocol is shown above. (B) Left panel: the mechanism of transient UCP1 current induced by long-chain low-pKa FA analogs added on the cytosolic face of the IMM. A long-chain FA− analog is translocated by UCP1 similar to short-chain FA−, however the long carbon tail of FA− establishes strong hydrophobic interaction with UCP1 to prevent FA− dissociation. Thus, the negatively charged FA− shuttles within the UCP1 translocation pathway in response to the transmembrane voltage, producing transient currents. These currents suggest that the UCP1 substrate binding site changes its position within the membrane during c-m conformation change. Right panel: an original trace of transient UCP1 current induced by long-chain low-pKa FA analogs. (C) Left panel: the mechanism of H+ current via UCP1 induced by regular long-chain FA added on the cytosolic face of the IMM. UCP1 operates as a symporter that transports one FA− and one H+ per the transport cycle. The H+ and the FA− are translocated by UCP1 upon a conformational change, and H+ is released on the opposite side of the IMM, while the FA− stays associated with UCP1 due to the hydrophobic interactions established by its carbon tail. The FA− anion then returns to initiate another H+ translocation cycle. Charge is translocated only in step 3 when the long chain FA anion returns without the H+. Right panel: an original trace of H+ current via UCP1 induced by regular long-chain FA.

Interestingly, UCP1 can bind and transport only cytosolic long-chain FA anions. Matrix long-chain FA anions, even when added at much higher concentrations, failed to induce UCP1 currents in the patch-clamp experiments [19]. In contrast, short-chain FA could activate UCP1 currents when added on any side of the IMM. This suggests that access to the substrate binding site on the matrix side of UCP1 is limited and long-chain FA cannot reach it due to their larger size.

Finally, the long-chain low-pKa FA anions are very effective inhibitors of the H+ currents activated by regular long-chain FA, suggesting that: 1) FA and H+ transport occur through the same translocation pathway; and 2) H+ binding to the polar head of the FA anion is essential for the H+ transport through UCP1. In conclusion, FA are likely to activate the H+ leak through UCP1 by serving as its transport substrates.

5. Mechanism of the FA-dependent H+ leak via UCP1

The new data on FA-UCP1 interaction obtained with the patch-clamp technique do not completely agree with any of the previously proposed models of UCP1 operation (Fig. 1). FA are essential for the activation of the H+ leak and serve as UCP1 transport substrates. Thus, the models in which FA activate the H+ leak via UCP1 allosterically and especially those in which UCP1 has a basal FA-independent H+ transport activity (the “H+ channel” or “OH−” channel in Fig. 1) cannot adequately explain the functional properties of UCP1. Although the “H+ buffering” and “FA-cycling” models agree better with the electrophysiological data, some important observations still remain unexplained. In particular, the “H+ buffering” model does not incorporate the fact that FA anions are UCP1 transport substrates. In regard to “FA-cycling”, this model requires binding of long-chain FA anions on the matrix side of the IMM to explain the H+ translocation into the mitochondrion, but long-chain FA anions cannot bind UCP1 on the matrix side[19].

Therefore, a new model of UCP1 operation, which represents the simplest explanation of all electrophysiological data, was proposed [19]. In this model, FA serves as a co-substrate for H+ transport by UCP1 (Fig. 3C). However, as mentioned above, long-chain FA are retained within UCP1 translocation pathway by hydrophobic interactions and essentially serve as carriers that help H+ transport through UCP1. In accordance with this model, a long-chain FA and H+ interact with the substrate binding site of UCP1 on the cytosolic face of the IMM (Fig. 3C). Upon a conformational change, the substrate binding site becomes exposed to the opposite side of the IMM and H+ is released in the mitochondrial matrix. However, FA remains anchored to UCP1 due to the hydrophobic interactions established by its long carbon tail, and upon another conformational change returns back to the cytosolic face of the IMM to initiate another transport H+ cycle. Although FA−/H+ transport through UCP1is electroneutral, the charge translocation is produced by the anionic headgroup of long-chain FA when, after releasing H+, it returns to the opposite side of the membrane (Fig. 3C).

The model of UCP1 operation presented in Fig. 3C assumes that UCP1 operates as a transporter rather than a channel. The previously estimated transport rate of UCP1, 0.3 H+ per second per mV of membrane potential [26], and a very small, undetectable, UCP1 unitary conductance observed in the patch-clamp experiments both support the conclusion that UCP1 operates as a transporter (channels normally conduct millions of ions per second). Interestingly, when UCP1 cannot bind one of its transported species (H+), it produces transient instead of steady currents in response to changes in membrane potential (Fig. 3B). Other transporters are also known to produce transient currents (so called pre-steady-state currents) in the absence of one of the transported substrates [27].

6. UCP1 function and SLC25 structural data

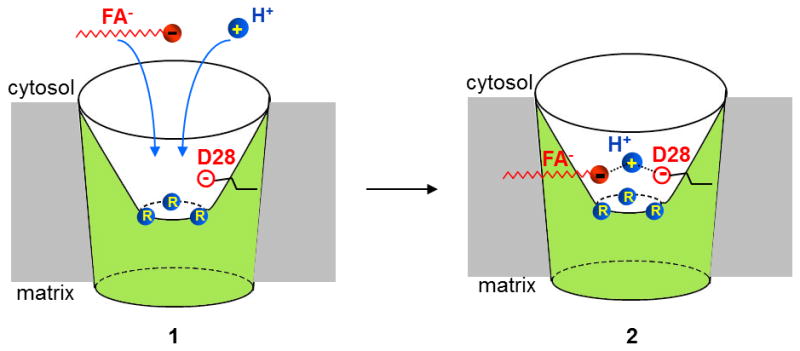

Based on sequence and symmetry analyses, all SLC25 family members are predicted to have one substrate-binding site (SBS) located near the centre of the membrane [23, 24]. During transport, this single SBS is believed to be intermittently exposed to different sides of the IMM as the carrier changes its conformation from a cytosolic to a matrix [22, 23]. The structures of two SLC25 members were solved in association with blockers that lock them in the cytosolic state: the ATP/ADP translocator with carboxyatractyloside [28] and UCP2 with GDP [29]. Although the validity of the UCP2 structure has been put in doubt [30], both carriers have a deep aqueous cavity on the cytosolic side with a putative SBS located within and exposed to the intermembrane space\cytosol (Fig. 4). The cytosolic state of all other carriers is predicted to have a similar architecture [22, 24].

Figure 4. Proposed substrate binding site of UCP1.

Predicted SBS of UCP1 before (1) and after (2) binding of an FA anion and H+. Arginines R84, R183, and R277 are shown in blue, and D28 is shown as an open red circle in the water-filled cytosolic cavity. H+ is stabilized between the carboxylic headgroup of FA and D28 (2).

Interestingly, the predicted SBS of UCP1 has three positively charged arginines (R84, R183, and R277) and a titratable residue (aspartate, D28), suggesting that UCP1 transports small carboxylic or keto acids in symport with H+ [23]. It was suggested that the positively charged arginines attract negatively charged head of FA anions into UCP1[23]. However, substitution of any one of the arginines with a neutral amino acid did not seem to affect H+ transport when mutant UCP1 was expressed in yeast[31]. Arguably, more than one arginine must be neutralized to prevent attraction of FA− and H+ translocation.

UCP1 residues that bind the hydrophobic tail of FA should be located near the SBS. Alternatively, the long hydrophobic tail could simply protrude into and be stabilized within the membrane. These hydrophobic interactions not only anchor long-chain FAs within UCP1, but also can help bring the anionic head of long-chain FA in close proximity to D28 (the hydrophobic interaction would be required to overcome electrostatic repulsion between the FA headgroup and D28) (Fig. 4). Thus, negatively charged D28 may serve as UCP1 selectivity filter that prevents penetration of small anions and only allows FA− that are stabilized by the hydrophobic interactions. The importance of hydrophobic FA tail in UCP1 binding (the longer the tail the smaller FA concentration is required to activate UCP1 currents) is consistent between the patch-clamp experiments and previous studies [2, 19, 32]. Interestingly, indirect studies in suspensions of isolated brown fat mitochondria reported a GDP-sensitive Cl− conductance presumably mediated by UCP1 [16, 33]. This anionic Cl− conductance was hard to reconcile with H+ transport by UCP1, and in early studies it was proposed that UCP1 may be an anion channel that transports OH− rather than H+ [16]. The UCP1 model presented here does not completely exclude transport of Cl− or OH−; however, because Cl− and OH− do not establish hydrophobic interactions with UCP1, their transport by UCP1 should be very limited due to the repulsion by D28. UCP1-mediated Cl− currents were too small to be detected by the patch-clamp technique, but Cl− could slightly affect the reversal potential of H+ currents [19].

The close proximity of the carboxylic headgroup of FA (solution pKa ~5) and anionic aspartate D28 (solution pKa ~4) could dramatically increase the pKa of the FA and D28, so that they can bind H+ at physiological pH (Fig. 4). Thus, in this model both the FA headgroup and D28 are required to stabilize a single H+ within the SBS, similar to what has been proposed for the mitochondrial phosphate carrier [22]. Thus, D28 seems to be important for both UCP1 selectivity filter and H+ permeation. Low-pKa FA analogs also bind to the SBS but cannot stabilize an H+, even together with D28, and translocation occurs without an H+, resulting in FA− currents only (Fig. 3). D28 is indispensable for H+ translocation by UCP1 [34].

What conformational changes does UCP1 undergo during the transport cycle? We propose that after initial binding of the anionic headgroup of FA to the SBS at the bottom of the cytosolic cavity, the UCP1 changes conformation to “engulf” FA and bring it within the membrane electric field (Fig. 5). Indeed, because low-pKa FA anions associated with UCP1 sense the membrane field and produce transient current in response to membrane voltage steps of different polarity (Fig. 3B), they must be located inside the UCP1 protein, not inside its water-filled cavity [19]. Furthermore, given that the anionic head is easily translocated by UCP1 in response to changes in transmembrane voltage (Fig. 3B)[19], we conclude that when associated with a FA substrate, UCP1 easily undergoes conformational changes. Both engulfment of the substrate upon binding to UCP1 and the easy conformational change of UCP1 thereafter are reminiscent of the “induced transition fit” principle once proposed for the ATP/ADP translocator [35]. In accordance with this principle, immediately after initial binding, the substrate induces a conformational change in the SBS (carrier optimally engulfs the substrate), so that the structure of the carrier becomes more flexible and easily switches between cytosolic and matrix states. Thus, we propose that in the long-chain FA-bound conformation of UCP1, the SBS with the attached FA headgroup is intermittently exposed to the cytosolic and matrix side to accomplish H+ transport (Fig. 5).

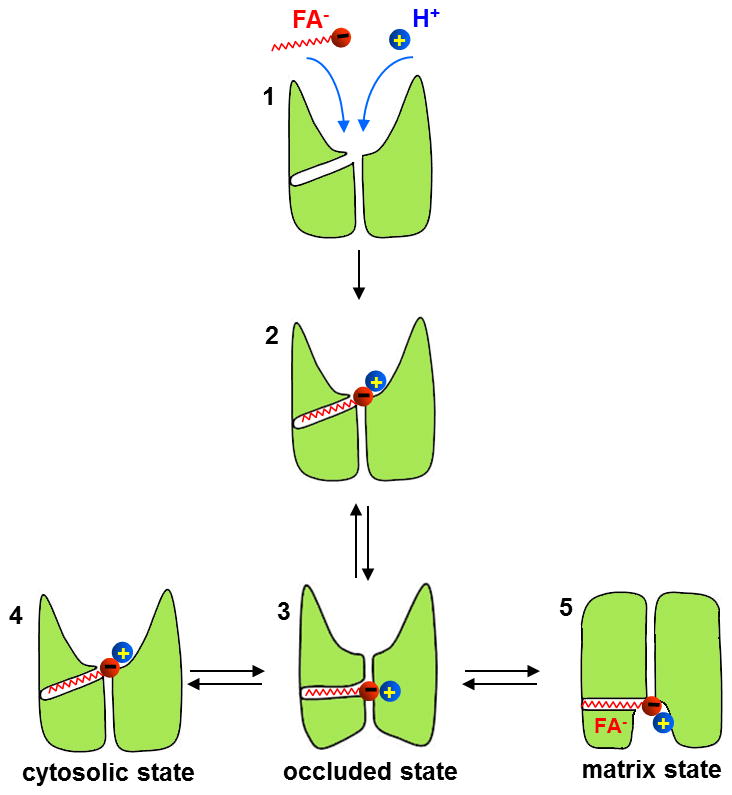

Figure 5. Proposed UCP1 conformational changes during the transport cycle.

After initial binding of the anionic long-chain FA and an H+ to the SBS (1 and 2, for simplicity D28 and arginines are omitted), UCP1 changes its conformation and the FA penetrates into the area that separates the cytosolic cavity and the matrix, within the membrane electric field (occluded state, 3). The structure of the substrate-bound UCP1 (3) is flexible, and it spontaneously transitions between the cytosolic state (4) and the matrix state (5) to expose the FA headgroup to different sides of the IMM and accomplish H+ transport.

This, however, does not necessarily mean that UCP1 cannot transition between cytosolic and matrix states without FA. Electrophysiological experiments demonstrate that low pKa short-chain FA analogs can be transported by UCP1 when present only on the cytosolic (or matrix) side of the IMM (Fig. 3a)[19]. This either means that 1) empty (FA-free) UCP1 can transition from matrix to cytosolic conformation without FA−, or 2) cytosolic FA−, being a hydrophobic substrate, can penetrate into the membrane and bind to the SBS even in the matrix conformation. Clearly, a combination of advanced electrophysiological and structural methods is required to shed more light on the molecular mechanism of UCP1 action.

7. The role of LCFAs in the removal of purine nucleotide inhibition of UCP1

All the properties of UCP1 discussed so far relate to UCP1 activity in the absence of purine nucleotides. However, in living cells, UCP1 is tonically inhibited by cytosolic purine nucleotides, primarily ATP. Purine nucleotides bind on the cytosolic side of UCP1 and seem to occlude the UCP1 translocation pathway [21, 29]. The identity of the molecule that overcomes the purine nucleotide inhibition and helps to activate UCP1-dependent thermogenesis in brown fat has remained elusive. Two primary candidates have been suggested: FAs and long chain acyl-CoA. However, results pertaining to the ability of either of these two molecules to overcome purine nucleotide inhibition have been controversial [2, 12, 32, 36].

In the patch-clamp experiments, long-chain FAs were able to overcome the inhibition of UCP1 by ATP [19] and therefore, should be able to do the same in vivo. This result is not surprising given that FA anions are permeable species and could compete with ATP4− that binds near or within the translocation pathway [21]. Due to the significant structural differences between FA anions and ATP4−, their binding sites on UCP1 cannot be identical. However, these binding sites may partially overlap or may simply be located in close proximity, so that the electrostatic repulsion between the two negatively charged species results in competition.

In the absence of purine nucleotides, even sub-micromolar concentrations of long-chain FAs can activate very large UCP1 currents [19]. Purine nucleotides reduce sensitivity of UCP1for long-chain FA to ensure that UCP1-dependent H+ leak is not activated by basal concentrations of FA. Due to the purine nucleotide inhibition, UCP1-dependent thermogenesis would only occur after stimulation of brown adipocytes by norepinephrine when the level of intracellular free FA is significantly elevated[11].

Although it has been proposed that acyl-CoA can overcome UCP1 inhibition by purine nucleotides [37, 38], patch-clamp data demonstrates that long chain acyl-CoA inhibits UCP1in low micromolar concentrations [19]. Long chain acyl-CoA contains a nucleotide and an acyl moieties. It is likely that the nucleotide moiety associates with the purine nucleotide binding site of UCP1, while the acyl moiety binds to hydrophobic pocket intended for the carbon tail of the long-chain FA. Thus, acyl-CoA is not an activator but rather inhibitor of UCP1. The physiological significance of such inhibition remains unclear, as well as the concentration of acyl-CoA achieved in the mitochondrial intermembrane space in vivo.

Although long-chain FA can overcome ATP inhibition in the patch-clamp experiments, this may not be the only physiological mechanism for the removal of UCP1 inhibition by purine nucleotides. In vivo, the removal of ATP inhibition can also be assisted by other mechanisms, such as the elevation of pH in the cytosol (or more locally, in the intermembrane space) [9], by the association of UCP1 with cardiolipin [21], or by a recently reported redox regulation of UCP1 [39].

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants 5R01GM107710 to Y.K.

References

- 1.Krauss S, Zhang CY, Lowell BB. The mitochondrial uncoupling-protein homologues. Nature reviews. 2005;6:248–261. doi: 10.1038/nrm1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rial E, Poustie A, Nicholls DG. Brown-adipose-tissue mitochondria: the regulation of the 32000-Mr uncoupling protein by fatty acids and purine nucleotides. Eur J Biochem. 1983;137:197–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klingenberg M, Winkler E. The reconstituted isolated uncoupling protein is a membrane potential driven H+ translocator. Embo J. 1985;4:3087–3092. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb04049.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aquila H, Link TA, Klingenberg M. The uncoupling protein from brown fat mitochondria is related to the mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier. Analysis of sequence homologies and of folding of the protein in the membrane. Embo J. 1985;4:2369–2376. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin CS, Klingenberg M. Characteristics of the isolated purine nucleotide binding protein from brown fat mitochondria. Biochemistry. 1982;21:2950–2956. doi: 10.1021/bi00541a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ricquier D, Kader JC. Mitochondrial protein alteration in active brown fat: a soidum dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoretic study. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1976;73:577–583. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(76)90849-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palmieri F. Mitochondrial transporters of the SLC25 family and associated diseases: a review. Journal of inherited metabolic disease. 2014;37:565–575. doi: 10.1007/s10545-014-9708-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicholls DG. A history of UCP1. Biochemical Society transactions. 2001;29:751–755. doi: 10.1042/bst0290751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nicholls DG, Locke RM. Thermogenic mechanisms in brown fat. Physiol Rev. 1984;64:1–64. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1984.64.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rial E, Gonzalez-Barroso MM. Physiological regulation of the transport activity in the uncoupling proteins UCP1 and UCP2. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1504:70–81. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00240-1. [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:277–359. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shabalina IG, Jacobsson A, Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Native UCP1 displays simple competitive kinetics between the regulators purine nucleotides and fatty acids. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38236–38248. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402375200. M402375200 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzalez-Barroso MM, Fleury C, Bouillaud F, Nicholls DG, Rial E. The uncoupling protein UCP1 does not increase the proton conductance of the inner mitochondrial membrane by functioning as a fatty acid anion transporter. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1998;273:15528–15532. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiménez-Jiménez J, Zardoya R, Ledesma A, García de Lacoba M, Zaragoza P, Mar González-Barroso M, Rial E. Evolutionarily Distinct Residues in the Uncoupling Protein UCP1 Are Essential for Its Characteristic Basal Proton Conductance. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2006;359:1010–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.04.022. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2006.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nicholls DG. The physiological regulation of uncoupling proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757:459–466. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicholls DG, Rial E. A history of the first uncoupling protein, UCP1. Journal of bioenergetics and biomembranes. 1999;31:399–406. doi: 10.1023/a:1005436121005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klingenberg M, Huang SG. Structure and function of the uncoupling protein from brown adipose tissue. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1415:271–296. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(98)00232-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garlid KD, Jaburek M, Jezek P. The mechanism of proton transport mediated by mitochondrial uncoupling proteins. FEBS letters. 1998;438:10–14. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fedorenko A, Lishko PV, Kirichok Y. Mechanism of Fatty-Acid-Dependent UCP1 Uncoupling in Brown Fat Mitochondria. Cell. 2012;151:400–413. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.010. S0092-8674(12)01113-0 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hille B. Ionic channels of excitable membranes. 2. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland, Mass: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klingenberg M. Wanderings in bioenergetics and biomembranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797:579–594. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.02.012. S0005-2728(10)00066-6 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kunji ER, Robinson AJ. Coupling of proton and substrate translocation in the transport cycle of mitochondrial carriers. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2010;20:440–447. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.06.004. S0959-440X(10)00100-4 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robinson AJ, Overy C, Kunji ER. The mechanism of transport by mitochondrial carriers based on analysis of symmetry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:17766–17771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809580105. 0809580105 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson AJ, Kunji ER. Mitochondrial carriers in the cytoplasmic state have a common substrate binding site. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2617–2622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509994103. 0509994103 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jezek P, Jaburek M, Garlid KD. Channel character of uncoupling protein-mediated transport. FEBS letters. 2010;584:2135–2141. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.02.068. S0014-5793(10)00172-9 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicholls DG. The effective proton conductance of the inner membrane of mitochondria from brown adipose tissue. Dependency on proton electrochemical potential gradient. Eur J Biochem. 1977;77:349–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peres A, Giovannardi S, Bossi E, Fesce R. Electrophysiological insights into the mechanism of ion-coupled cotransporters. News Physiol Sci. 2004;19:80–84. doi: 10.1152/nips.01504.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pebay-Peyroula E, Dahout-Gonzalez C, Kahn R, Trezeguet V, Lauquin GJ, Brandolin G. Structure of mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier in complex with carboxyatractyloside. Nature. 2003;426:39–44. doi: 10.1038/nature02056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berardi MJ, Shih WM, Harrison SC, Chou JJ. Mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 structure determined by NMR molecular fragment searching. Nature. 2011;476:109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature10257. nature10257 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zoonens M, Comer J, Masscheleyn S, Pebay-Peyroula E, Chipot C, Miroux B, Dehez F. Dangerous liaisons between detergents and membrane proteins. The case of mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2013;135:15174–15182. doi: 10.1021/ja407424v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Echtay KS, Bienengraeber M, Klingenberg M. Role of intrahelical arginine residues in functional properties of uncoupling protein (UCP1) Biochemistry. 2001;40:5243–5248. doi: 10.1021/bi002130q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winkler E, Klingenberg M. Effect of fatty acids on H+ transport activity of the reconstituted uncoupling protein. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:2508–2515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nicholls DG, Lindberg O. Brown-adipose-tissue mitochondria. The influence of albumin and nucleotides on passive ion permeabilities. Eur J Biochem. 1973;37:523–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1973.tb03014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Echtay KS, Winkler E, Bienengraeber M, Klingenberg M. Site-directed mutagenesis identifies residues in uncoupling protein (UCP1) involved in three different functions. Biochemistry. 2000;39:3311–3317. doi: 10.1021/bi992448m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klingenberg M. The ADP and ATP transport in mitochondria and its carrier. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:1978–2021. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.04.011. S0005-2736(08)00144-2 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang SG. Binding of fatty acids to the uncoupling protein from brown adipose tissue mitochondria. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2003;412:142–146. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(03)00031-6. [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cannon B, Sundin U, Romert L. Palmitoyl coenzyme A: a possible physiological regulator of nucleotide binding to brown adipose tissue mitochondria. FEBS letters. 1977;74:43–46. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(77)80748-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katiyar SS, Shrago E. Differential interaction of fatty acids and fatty acyl CoA esters with the purified/reconstituted brown adipose tissue mitochondrial uncoupling protein. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1991;175:1104–1111. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91679-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chouchani ET, Kazak L, Jedrychowski MP, Lu GZ, Erickson BK, Szpyt J, Pierce KA, Laznik-Bogoslavski D, Vetrivelan R, Clish CB, et al. Mitochondrial ROS regulate thermogenic energy expenditure and sulfenylation of UCP1. Nature. 2016;532:112–116. doi: 10.1038/nature17399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]