Abstract

Object Endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery is the commonest approach to pituitary tumors. One disadvantage of this approach is the development of early postoperative nasal symptoms. Our aim was to clarify the peak onset of these symptoms and their temporal evolution.

Methods The General Nasal Patient Inventory (GNPI) was administered to 56 patients undergoing endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery for pituitary tumors preoperatively and at 1 day, 3 days, 2 weeks, 3 months, and 6 to 12 months postoperatively. Most patients underwent surgery for pituitary adenomas ( N = 49; 88%) and through a uninostril approach ( N = 55; 98%). Total GNPI (0–135) and scores for the 45 individual components were compared.

Results GNPI scores peaked at 1 to 3 days postoperatively, with rapid reduction to baseline by 2 weeks and below baseline by 6 to 12 months postsurgery ( p < 0.01). Of the 45 individual symptoms on the GNPI scale, 19 (42%) worsened transiently after surgery ( p < 0.05). Functioning tumors had a higher GNPI scores at postoperative day 1 and 3 than nonfunctioning tumors, although their temporal evolution was the same ( p < 0.05).

Conclusions Nasal morbidity following endoscopic transsphenoidal pituitary surgery is common, but transient, more so in the functioning subgroup. Nasal symptoms improve below baseline by 6 to 12 months, without the need for specific long-term postoperative interventions in the vast majority of patients.

Keywords: endoscopic, transsphenoidal, pituitary tumor, adenoma, nasal symptoms, GNPI

Introduction

The endoscopic transsphenoidal approach for pituitary surgery is now the favored approach to the pituitary fossa, having progressively replaced the microscopic approach in most centers over the last 10 to 15 years. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 The cranial approaches are mostly reserved for residual pituitary tumors that are deemed too difficult to resect through the transsphenoidal route. The popularity of the endoscopic approach is in part due to the improved surgical access, visibility, the potential for greater tumor resection, reduced nasal trauma, and thus shorter hospital stay and greater patient satisfaction. 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

With the transsphenoidal approach, patients frequently report nasal symptoms such as nasal discharge, congestion, bleeding, crusting, pain, and loss of smell shortly after surgery. Strategies to combat and/or prevent these symptoms vary widely and include the use of postoperative nasal decongestants, saline irrigation, and endoscopic debridement in the outpatient setting. 1 2 4 12 13

We and others have previously reported on the prevalence of postoperative patient-perceived rhinological symptoms following endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery 4 6 8 14 15 16 Using the validated General Nasal Patient Inventory (GNPI) questionnaire, we identified that by 3 to 6 months postoperatively, the majority of patient undergoing endoscopic surgery for pituitary tumors were largely asymptomatic from a nasal point of view. 4 However, the temporal evolution of these symptoms in the early postoperative period remains less clear. This remains of interest when considering the treatment length of preventative therapies.

In this study, we more closely evaluated the onset and early progression of patient-perceived nasal symptoms following endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery for pituitary tumors by administering the GNPI preoperatively and at 1 day, 3 days, 2 weeks, 3 and 6 to 12 months postoperatively.

Method

Patients undergoing transsphenoidal pituitary surgery for pituitary tumors by a single surgeon over an 18-month period (2007–2009) were approached to complete an audit questionnaire prospectively. Of the 58 patients, 56 provided complete follow-up data and were included for analysis. Patient demographics, tumor type, operative details (including cerebrospinal fluid [CSF] leak and method of repair), and complications (including hemorrhage and intervention for ongoing nasal symptoms) were recorded.

Operative Technique

All patients underwent endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery as described previously. 1 4 Cophenylcaine (Aurum Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Romford, United Kingdom) was applied to both nostrils as preoperative nasal preparation. Perioperatively, all patients received a single dose of antibiotics (intravenous cefuroxime and metronidazole). No antiseptic nasal wash or other vasoconstrictors were routinely used during surgery. Typically, surgical approach was through a single nostril, the side chosen taking into account the laterality of the tumor and any anomaly in nasal anatomy. On occasion, surgery required the use of both nostrils, with a small posterior septostomy. The middle turbinate was gently lateralized and turbinectomy (partial or complete) was not performed. The posterior nasal septal mucosa overlying the anterior sphenoid wall, on the side of the approach, was cauterized before opening the sphenoid sinus. The sphenoid sinus mucosa was reflected laterally using cotton patties. In the event of CSF leakage, a graded operative repair was undertaken using combinations of hemostatic gelatin sponge (Spongostan, Ethicon, Edinburgh, United Kingdom), dural substitute (Durafoam, Codman, United Kingdom), and dural sealant (Duraseal, Confluent Surgical, Waltham, Massachusetts) for grade 1 leaks (minor leak with no obvious arachnoid defect). 1 In the event of a grade 2 (i.e., moderate CSF leak with visible arachnoid defect) or grade 3 CSF leak (i.e., large CSF leak with large dural defect), in addition to the aforementioned combinations, a fat graft and/or vascularized nasoseptal flap was used on a selective basis. 1

At the end of tumor removal, nasal cavities in both nostrils were inspected and any significant mucosal bleeding points were controlled with diathermy. The deflected middle turbinate and nasal septum were medialized and nasal packing was not routinely employed.

Postoperative Course

A topical nasal decongestant (Xylometazoline 0.1% spray, Novartis, Surrey, United Kingdom) was prescribed for 7 days postoperatively. Additional therapies, such as saline irrigation, nasal debridement, and review by an otolaryngologist, were not routinely undertaken and only considered for those patients with persistent nasal symptoms, in conjunction with otolaryngologist referral.

Nasal Symptoms

The GNPI is a patient reported outcome tool developed to cover all rhinological conditions. 14 The GNPI questionnaire considers 45 different nasal symptoms and patients choose one of 4 numerical answers for each: 0 (not present), 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), or 3 (severe). Therefore, the higher the score, the greater the symptom burden; the score ranges between 0 and 135.

In this study, patients completed the GNPI questionnaire preoperatively and at 1 day, 3 days, 2 weeks, 3 months, and 6 to 12 months postoperatively. The 45 individual nasal symptoms and the total GNPI score (range: 0–135) at each time points were analyzed.

Statistical Analysis

Analysis was performed using SPSS (version 20, Chicago, Illinois, United States). Comparison between time points was assessed using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), with posthoc Bonferroni tests for parametric data and the chi-square tests for nonparametric data.

Results

Population Characteristics

Mean patient age (±SD) was 58 ± 16 years (range: 23–87) and both sexes were equally represented (M:F 27:29). The majority of patients ( N = 33; 60%) had nonfunctioning pituitary adenomas. The functioning tumors included acromegaly ( N = 6; 11%), Cushing syndrome ( N = 6; 11%), and prolactinomas ( N = 3; 5%). The remainder included Rathke's cysts ( N = 4; 7%), one each of a craniopharyngioma, squamoid cyst, pituitary apoplexy, and a mucocoele. GNPI scores did not differ between adenomas and the small number of nonadenomas ( N = 8) and were analyzed together ( p = 0.8; ANOVA). The majority of lesions were macroadenomas ( N = 40; 83%). Baseline demographics are summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1. Baseline patient demographics.

| Covariate | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Male | 27 (48) |

| Functional | 15 (27) |

| Macro Micro Nonadenoma |

40 (71) 8 (14) 8 (14) |

| Uninostril approach | 55 (98) |

| CSF leak | 20 (36) |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 58 ± 16 |

Abbreviation: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; SD, standard deviation.

Note: Percentages are expressed as a proportion of patients with complete follow-up data ( N = 56).

Procedural Variation and Complications

The majority ( N = 55; 98%) of procedures were undertaken through a single nostril, and none of the patients required postoperative nasal packing. In this series, no patients underwent extended endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery for other skull base pathology. Intraoperative CSF leaks complicated 20 (36%) procedures. These were grade 1 ( N = 19) and grade 2 ( N = 1) CSF leaks. Repairs were made with a combination gelatin sponge (Spongostan), dural substitute (Durafoam), and dural sealant (Duraseal) as described previously. 1 No fat grafts were used, and the repair was effective in all but two patients (i.e., one patient with Cushing disease and another with a Rathke's cyst), who represented with recurrent CSF leaks that were successfully treated with lumbar drains ( N = 2) and further transsphenoidal repair ( N = 1).

On discharge, three patients suffered early postoperative nose bleeds, requiring readmission and management with nasal packing, oral antibiotics ( N = 3), and transfusion/cautery ( N = 1). One patient was reviewed at 3 months in an ear, nose, and throat clinic with symptoms of persistent nasal crusting and headaches that responded to a course of steroid nasal spray and saline irrigation.

General Nasal Patient Inventory Scores

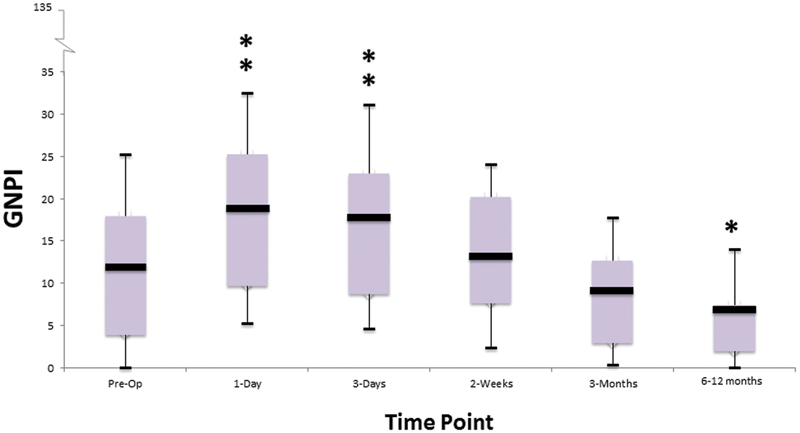

Out of a maximum score of 135, the mean postoperative GNPI scores peaked at day 1 (19 ± 14), before gradually returning to baseline at 2 weeks ( p < 0.01, repeated measures ANOVA and posthoc Bonferroni test; Fig. 1 ). The mean GNPI score at 6 to 12 months follow-up (6.7 ± 7) was significantly lower than the preoperative baseline ( p = 0.03, repeated measures ANOVA and posthoc Bonferroni test; Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Changes in total General Nasal Patient Inventory scores over time. Box plots depict the mean (horizontal black line), interquartile range (box), and the standard deviation values (tails). * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01 versus preoperative value; repeated measures analysis of variance and posthoc Bonferroni test.

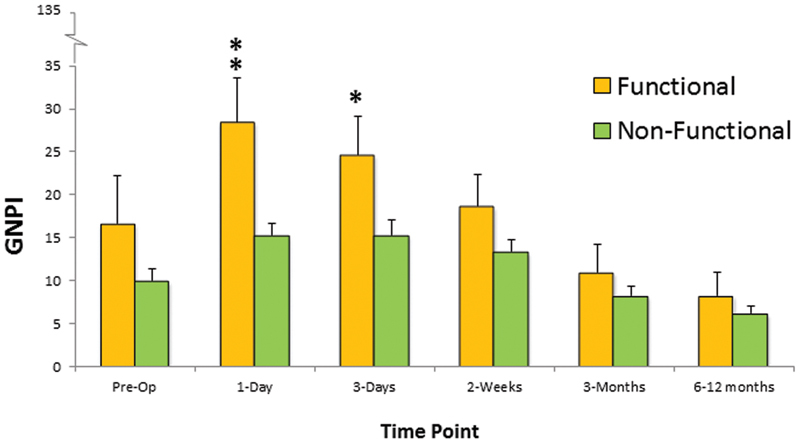

Functioning tumors had a higher GNPI score than the corresponding score for the nonfunctioning tumor types, at day 1 and day 3 ( p = 0.02, repeated measures ANOVA and posthoc Bonferroni test; Fig. 2 ). Age ( p = 0.1) and patient sex ( p = 0.6) were not associated with the mean GNPI scores (repeated measures ANOVA). The postoperative trends in GNPI scores did not significantly interact for patients suffering a CSF leak ( p = 0.4, repeated measures ANOVA).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the total General Nasal Patient Inventory scores (mean ± standard error) over time for functioning compared with nonfunctioning pituitary tumors. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01 versus corresponding score for the other group at same time point; repeated measures analysis of variance and posthoc Bonferroni test.

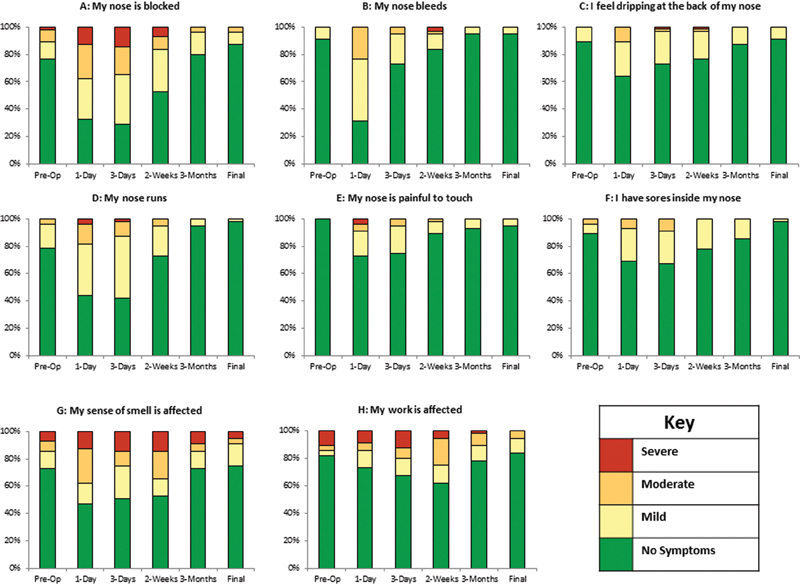

Of the 45 individual symptoms considered by the GNPI, 19 (42%) showed significant variation across different time points during follow-up ( p < 0.05, chi-square test; Table 2 ). All of these symptoms improved to or beyond baseline at 6 to 12 months postoperatively ( Table 2 ). The majority of these symptoms (18/19; 95%) peaked between 1 to 3 days following the operation ( Fig. 3 ). Only the GNPI symptom, “my work is affected” peaked at 2 weeks postoperatively ( Fig. 3 ).

Table 2. The GNPI and the evolution of symptoms over time.

| Symptom | Preoperative (%) | Postoperative (%) | Chi-square p -value |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 d | 3 d | 2 wk | 3 mo | 6–12 mo | ||||

| 1 | I have sores inside my nose | 89 | 70 | 68 | 79 | 86 | 98 | <0.0001 |

| 2 | I get headaches | 59 | 46 | 39 | 45 | 54 | 63 | 0.07 |

| 3 | I take too many painkillers | 82 | 73 | 82 | 86 | 82 | 84 | 0.79 |

| 4 | There is an unpleasant smell in my nose | 93 | 98 | 91 | 84 | 88 | 91 | 0.4 |

| 5 | My nose bleeds | 91 | 32 | 73 | 82 | 95 | 95 | <0.0001 |

| 6 | My sinuses are painful | 89 | 84 | 75 | 71 | 89 | 95 | 0.07 |

| 7 | My nose is blocked | 77 | 34 | 29 | 52 | 80 | 88 | <0.0001 |

| 8 | I feel dripping at the back of my nose | 89 | 63 | 71 | 75 | 88 | 91 | 0.001 |

| 9 | I have an unpleasant taste in my mouth | 82 | 80 | 71 | 68 | 77 | 89 | 0.24 |

| 10 | I have feelings of nausea | 84 | 77 | 77 | 88 | 93 | 96 | 0.04 |

| 11 | My mouth is dry | 68 | 38 | 32 | 48 | 64 | 75 | <0.0001 |

| 12 | My nose feels uncomfortable | 89 | 55 | 45 | 61 | 88 | 91 | <0.0001 |

| 13 | My taste is affected | 84 | 70 | 57 | 61 | 75 | 79 | 0.03 |

| 14 | My work is affected | 82 | 73 | 68 | 63 | 79 | 84 | 0.04 |

| 15 | My voice changes | 79 | 68 | 71 | 82 | 93 | 95 | 0.01 |

| 16 | My jaws are sore | 89 | 86 | 91 | 89 | 96 | 98 | 0.35 |

| 17 | I feel tired | 45 | 25 | 18 | 18 | 36 | 39 | 0.02 |

| 18 | I have sore ears | 89 | 89 | 96 | 95 | 96 | 96 | 0.67 |

| 19 | My nose makes unusual noises | 91 | 82 | 80 | 80 | 89 | 93 | 0.4 |

| 20 | My sleep is disturbed | 59 | 39 | 43 | 52 | 63 | 68 | 0.23 |

| 21 | My nose is painful to touch | 100 | 73 | 75 | 89 | 93 | 95 | <0.0001 |

| 22 | My sense of smell is affected | 73 | 48 | 52 | 54 | 73 | 75 | 0.01 |

| 23 | I have a choking feeling | 96 | 95 | 93 | 93 | 96 | 96 | 0.73 |

| 24 | My nose looks out of shape | 89 | 88 | 89 | 93 | 98 | 98 | 0.49 |

| 25 | I have sneezing attacks | 80 | 88 | 88 | 82 | 84 | 88 | 0.4 |

| 26 | I have pains in my face | 89 | 88 | 80 | 88 | 95 | 96 | 0.48 |

| 27 | I have to breathe through my mouth | 89 | 48 | 45 | 57 | 84 | 95 | <0.0001 |

| 28 | I suffer from hayfever | 89 | 93 | 93 | 93 | 93 | 93 | 0.88 |

| 29 | I have difficulty breathing | 96 | 80 | 82 | 91 | 91 | 96 | 0.09 |

| 30 | I have difficulty talking or eating | 93 | 89 | 89 | 89 | 96 | 96 | 0.71 |

| 31 | I have sore watering eyes | 71 | 75 | 79 | 73 | 84 | 86 | 0.5 |

| 32 | I feel moody, depressed, or irritable | 71 | 88 | 73 | 66 | 71 | 79 | 0.59 |

| 33 | My nose feels itchy | 89 | 88 | 82 | 80 | 84 | 95 | 0.71 |

| 34 | I am constantly sniffing | 91 | 64 | 61 | 68 | 93 | 100 | <0.0001 |

| 35 | My hearing is affected | 86 | 89 | 95 | 91 | 95 | 95 | 0.82 |

| 36 | I speak through my nose | 88 | 64 | 64 | 75 | 86 | 91 | <0.0001 |

| 37 | I have a sore throat | 88 | 73 | 84 | 96 | 96 | 100 | <0.0001 |

| 38 | My gums bleed | 86 | 96 | 98 | 98 | 100 | 100 | 0.001 |

| 39 | I feel dizzy | 79 | 71 | 75 | 73 | 86 | 89 | 0.61 |

| 40 | I suffer from a cough | 84 | 71 | 79 | 88 | 91 | 93 | 0.52 |

| 41 | People ask me if I have a cold | 77 | 75 | 68 | 77 | 93 | 96 | 0.001 |

| 42 | My nose runs | 79 | 43 | 43 | 73 | 93 | 96 | <0.0001 |

| 43 | I snore | 43 | 46 | 48 | 48 | 46 | 48 | 0.97 |

| 44 | I have bad breath | 77 | 77 | 84 | 84 | 86 | 89 | 0.95 |

| 45 | I get toothache | 82 | 88 | 93 | 91 | 91 | 100 | 0.16 |

Abbreviation: GNPI, General Nasal Patient Inventory.

Note: Percentage of asymptomatic patients at each time point ( N = 56). The p -value indicates whether there was significant change in a symptom over time (chi-square test).

Fig. 3.

Temporal evolution of selected nasal symptoms. (A) My nose is blocked. (B) My nose bleeds. (C) I feel dripping at the back of my nose. (D) My nose runs. (E) My nose is painful to touch. (F) I have sores inside my nose. (G) My sense of smell is affected. (H) My work is affected. All symptoms peaked at 1 to 3 days postoperatively with the exception of “My work is affected” (H) .

Discussion

The main findings of this study were that the majority of patients reported some nasal morbidity following transsphenoidal endoscopic pituitary surgery, more so among patients with functional adenomas. Regardless, the nasal symptoms were relatively mild and recovered quickly and with minimal input postoperatively. Our findings indicate that the majority of symptoms peak at 1 to 3 days and show rapid improvement by 2 weeks thereafter. This and the discrepancies between functioning and nonfunctioning adenomas, alongside the very early recovery without significant intervention, represent new findings in transsphenoidal endoscopic surgery.

A variety of scoring systems have been developed to evaluate patient experience of nasal symptoms following pituitary surgery. 3 4 7 8 16 Most of these scales have been validated in patients with rhinological conditions, and only a few, such as the anterior skull base nasal inventory (ASK Nasal-12), have been validated in the pituitary surgery patient group. 8 In this study, the GNPI was used primarily to allow comparison with the results of our previous study. 4 The GNPI inventory provides a comprehensive list of possible nasal symptoms and includes the more refined symptom list of the anterior skull base nasal inventory.

A significant difference in postoperative patient reported nasal morbidity between functioning and nonfunctioning tumors was observed 1 to 3 days after surgery. This has not been previously described in other studies. This may in part be due to previous studies considering later postoperative time points, when as mirrored in our study there is no difference. 2 3 4 The higher GNPI scores in the functioning group of tumor patients may reflect the influence of excess hormone production. Thus, for example, the growth hormone excess in acromegaly is associated with hypertrophy of nasal passages and pharyngeal tissues, leading to increased nasal symptoms and sleep apnea preoperatively. 1 17 18 Likewise, excess cortisol production in Cushing disease is likely to delay early postoperative healing in the nasal passages. 1 19 Reassuringly, the increase in GNPI scores in the functioning group is short lived and beyond 2 weeks, and there is little difference when compared with nonfunctioning tumor patients. The improvement in symptoms in the functioning group is likely related to reduction in excess hormone production in functioning tumors postoperatively. Consistent with our observations, Actor et al demonstrated a more pronounced improvement in olfaction and nasal patency among patients with acromegaly compared with others, a change likely due to the reduction in nasal hypertrophy postoperatively and related to reduction in growth hormone levels postoperatively. 1 17

The overall mean GNPI score at 6 to 12 months follow-up was lower than the preoperative baseline. This was also apparent in the progressive improvements in several individual symptoms considered by the GNPI such as “I get headaches,” “My nose is blocked,” “My voice changes,” and “I get toothache.” The progressive improvement in the overall GNPI score may reflect the reduction in mass effect and improved quality of life secondary to pituitary tumor surgery and the normalization of hormonal excesses in functioning adenomas.

Given the prevalence of early postoperative nasal symptoms following transsphenoidal surgery for pituitary tumors, most patients require ongoing postoperative nasal care on discharge. 2 14 20 However, the exact practice differs widely across centers in part due to the relative lack of evidence basis to guide postoperative therapies following endoscopic pituitary surgery. 1 2 20 In our unit, where endoscopic surgery for most pituitary tumors is typically undertaken through a uninostril approach, the use of a topical nasal decongestant for a short period (i.e., 1 week) postoperatively is preferred. Others recommend a more interventional approach including outpatient endoscopic debridement and/or a longer course of topical nasal agents such as saline irrigation. 2 15 We reserve these measures mostly for the extended transsphenoidal cases, typically requiring a binostril approach, with a partial or complete middle turbinectomy and/or a nasoseptal flap, resulting in greater nasal morbidity. Likewise the use of perioperative broad spectrum antibiotics is common practice in endoscopic pituitary surgery. However, routine provision of postoperative antibiotics is not common, and we prefer to reserve this for extended transnasal procedures, particularly where a temporary nasal packing is used to support the repair.

Despite the different approaches, and accepting the caveats of interstudy comparison, the results from several recent studies including the present confirm that the proportion of patients with persistent nasal symptoms after endoscopic pituitary surgery is relatively small. 4 6 8 15 21 These observations together with findings of recent meta-analysis reaffirm the efficacy and safety of the endoscopic approach in relationship to the more established microscopic approach. 5 6

Footnotes

Disclosure The results of this study have been presented at the International Society of Pituitary Surgeons, Liverpool, United Kingdom, November 2015.

References

- 1.Zador Z, Gnanalingham K. Endoscopic transnasal approach to the pituitary--operative technique and nuances. Br J Neurosurg. 2013;27(06):718–726. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2013.798862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Little A S, Kelly D, Milligan J et al. Predictors of sinonasal quality of life and nasal morbidity after fully endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery. J Neurosurg. 2015;122(06):1458–1465. doi: 10.3171/2014.10.JNS141624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCoul E D, Anand V K, Schwartz T H. Improvements in site-specific quality of life 6 months after endoscopic anterior skull base surgery: a prospective study. J Neurosurg. 2012;117(03):498–506. doi: 10.3171/2012.6.JNS111066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Y Y, Srirathan V, Tirr E, Kearney T, Gnanalingham K K. Nasal symptoms following endoscopic transsphenoidal pituitary surgery: assessment using the General Nasal Patient Inventory. Neurosurg Focus. 2011;30(04):E12. doi: 10.3171/2011.1.FOCUS10319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao Y, Zhong C, Wang Y et al. Endoscopic versus microscopic transsphenoidal pituitary adenoma surgery: a meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:94. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-12-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Little A S, Kelly D F, Milligan J et al. Comparison of sinonasal quality of life and health status in patients undergoing microscopic and endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery for pituitary lesions: a prospective cohort study. J Neurosurg. 2015;123(03):799–807. doi: 10.3171/2014.10.JNS14921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirkman M A, Borg A, Al-Mousa A, Haliasos N, Choi D. Quality-of-life after anterior skull base surgery: a systematic review. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2014;75(02):73–89. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1359303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Little A S, Kelly D, Milligan J et al. Prospective validation of a patient-reported nasal quality-of-life tool for endonasal skull base surgery: The Anterior Skull Base Nasal Inventory-12. J Neurosurg. 2013;119(04):1068–1074. doi: 10.3171/2013.3.JNS122032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fathalla H, Cusimano M D, Alsharif O M, Jing R. Endoscopic transphenoidal surgery for acromegaly improves quality of life. Can J Neurol Sci. 2014;41(06):735–741. doi: 10.1017/cjn.2014.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaillard S.The transition from microscopic to endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery in high-caseload neurosurgical centers: the experience of Foch Hospital World Neurosurg 201482(6, Suppl):S116–S120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jane J A, Jr, Han J, Prevedello D M, Jagannathan J, Dumont A S, Laws E R., Jr Perspectives on endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;19(06):E2. doi: 10.3171/foc.2005.19.6.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Humphreys H. Preventing surgical site infection. Where now? J Hosp Infect. 2009;73(04):316–322. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Little A S, Chapple K, Jahnke H, White W L. Comparative inpatient resource utilization for patients undergoing endoscopic or microscopic transsphenoidal surgery for pituitary lesions. J Neurosurg. 2014;121(01):84–90. doi: 10.3171/2014.2.JNS132095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Douglas S A, Marshall A H, Walshaw D, Robson A K, Wilson J A. The development of a General Nasal Patient Inventory. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2001;26(05):425–429. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.2001.00497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balaker A E, Bergsneider M, Martin N A, Wang M B. Evolution of sinonasal symptoms following endoscopic anterior skull base surgery. Skull Base. 2010;20(04):245–251. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1249248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dusick J R, Esposito F, Mattozo C A, Chaloner C, McArthur D L, Kelly D F.Endonasal transsphenoidal surgery: the patient's perspective-survey results from 259 patients Surg Neurol 20066504332–341., discussion 341–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Actor B, Sarnthein J, Prömmel P, Holzmann D, Bernays R L. Olfactory improvement in acromegaly after transnasal transsphenoidal surgery. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;29(04):E10. doi: 10.3171/2010.7.FOCUS10162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leach P, Abou-Zeid A H, Kearney T, Davis J, Trainer P J, Gnanalingham K K. Endoscopic transsphenoidal pituitary surgery: evidence of an operative learning curve. Neurosurgery. 2010;67(05):1205–1212. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e3181ef25c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wicke C, Halliday B, Allen D et al. Effects of steroids and retinoids on wound healing. Arch Surg. 2000;135(11):1265–1270. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.11.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rudmik L, Soler Z M, Orlandi R R et al. Early postoperative care following endoscopic sinus surgery: an evidence-based review with recommendations. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2011;1(06):417–430. doi: 10.1002/alr.20072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Almeida J R, Snyderman C H, Gardner P A, Carrau R L, Vescan A D. Nasal morbidity following endoscopic skull base surgery: a prospective cohort study. Head Neck. 2010;33(04):547–551. doi: 10.1002/hed.21483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]