Abstract

We directly assessed mesial temporal activity in two Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients without a history or EEG evidence of seizures, using intracranial foramen ovale electrodes. We detected clinically silent hippocampal seizures and epileptiform spikes during sleep, a period when both were most likely to interfere with memory consolidation. These index cases support a model in which early development of occult hippocampal hyperexcitability may contribute to the pathogenesis of AD.

One century ago, microscopic analysis of brain tissue from a single patient, Auguste Deter, established a link between amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and severe memory loss1. Amyloid plaques were, in fact, first described by Blocq and Marinesco in 1892, in patients with epilepsy2. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and epilepsy both impair cognition and manifest overlapping patterns of cellular neurodegeneration and hypometabolism in the temporal lobe3. Despite extraordinary advances in the molecular pathology of AD4, the structural basis for the early fluctuating course of cognitive decline in AD remains elusive and cannot be explained from purely microscopic or macroscopic pathological standpoints. Correlation of cognitive deficits with amyloid plaque load is weak5, comparable brain atrophy can be seen in cognitively normal adults6 and in non-dementing diseases (including epilepsy)7, and a fluctuating course is not easily explained by a monotonic process of progressive cell death. Interneurons are among the first to die in AD mesial temporal cortex8, however, and the ensuing degradation of synaptic connectivity and circuit remodeling could disrupt network oscillations that contribute to memory storage and retrieval. Intermittent temporal lobe dysrhythmia could therefore account for early fluctuations in cognition in AD patients. Here, we used intracranial electrodes inserted through the foramen ovale (FO) and positioned adjacent to the mesial temporal lobe (mTL)9 to directly assess, for the first time, mTL activity in two patients with AD and fluctuating cognition.

The first patient examined was a 67 year-old woman with no seizure history who developed cognitive decline over one year, punctuated by confusional episodes described as hours of repetitive questioning and garbled speech that required days for full recovery. Neuropsychological testing demonstrated amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Additional clinical details are reported in the Supplementary Information.

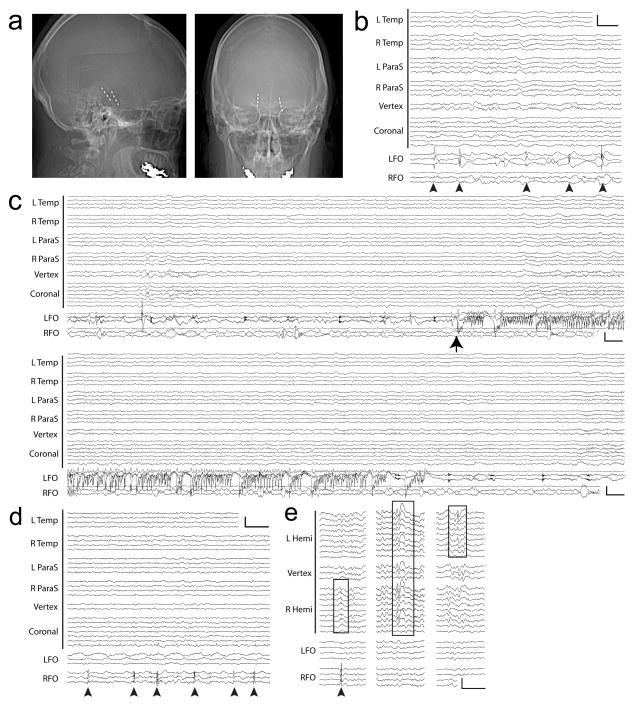

Brain MRI showed diffuse atrophy, and 18FDG-PET demonstrated left temporoparietal hypometabolism (Supp. Figure 1a,b). A 35-minute scalp EEG obtained during sleep showed normal sleep architecture including spindles and K-complexes, and no evidence of focal slowing or epileptiform discharges. CSF analysis showed an amyloid-tau index of 0.44 (<1.0 abnormal) and a phosphorylated tau level of 95.9 pg/mL (>61 abnormal), consistent with a diagnosis of AD. Genetic testing revealed APOE3/4 alleles but no exome variants in three known familial AD genes (Supp. Figure 2). On continuous video-EEG monitoring, left temporal sharp waves were seen at a rate of ~2/hour during wakefulness and ~40–70/hour during sleep. Rare right temporal sharp waves also occurred during sleep (~5/hour). Based on a high index of suspicion for occult seizures, the patient was implanted with bilateral FO electrodes targeting the mTL (Figure 1a). Intracranial recordings from these electrodes revealed abundant mTL spiking (~400/hour during wakefulness and up to ~850/hour during sleep), with 85% of spikes arising from the left mTL. The majority (95%) of spikes detected on FO electrodes were not evident on scalp EEG (Figure 1b). During the first of 12 hours of recording, the patient had three subclinical seizures arising from the left mTL, all occurring during sleep (Figure 1c). Scalp EEG during these seizures showed no ictal activity. One seizure was associated with awakening from sleep, while the others had no overt clinical manifestations. The patient was treated with levetiracetam, a common anti-epileptic drug that has been shown to reduce abnormal spiking activity in animal models of AD10 and to reduce hippocampal hyperactivity in humans with amnestic mild cognitive impairment11. Levetiracetam binds to SV2A12, a synaptic vesicle protein that regulates neurotransmitter release, though the exact mechanism of levetiracetam’s anticonvulsant effect is unknown. After starting levetiracetam (1500mg/day), no further seizures were captured on FO electrodes over the following 48 hours prior to their removal, and spike frequency was reduced by 65%. Twelve months later, she reported one spell of confusion following several consecutively missed doses of levetiracetam. Repeat neuropsychological testing showed mild progression of her cognitive deficits.

Figure 1.

Subclinical mTL seizures and spikes captured with FO electrodes in two AD patients. (A–C): Patient #1. A. Skull x-rays demonstrating radiopaque FO electrodes, with lateral (left) and anterior-posterior (right) views. B. Left mTL spikes (arrowheads), without scalp EEG correlate. Calibration scale: 200uV, 1 sec. C. Electrographic seizure from the left mTL (arrow), without scalp EEG ictal correlate. Panels show continuous EEG spanning 60 seconds. Calibration scale: 150uV, 1 sec. (D–E): Patient #2. D. Right mTL spikes (arrowheads), without scalp EEG correlate. Calibration scale: 200uV, 1 sec. E. Three types of epileptiform discharges. Left: Right mTL spike (arrowhead) with scalp EEG correlate resembling benign epileptiform transient of sleep (box). Middle: Bifrontal spike-wave on scalp EEG (box) without FO correlate. Right: Left temporal sharp wave on scalp EEG (box) without FO correlate. Calibration scale: 200uV, 1 sec. (B–D): Anterior-posterior bipolar montage. L Temp = left temporal (Fp1-F7, F7-T3, T3-T5, T5-O1), R Temp = right temporal (Fp2-F8, F8-T4, T4-T6, T6-O2), L ParaS = left parasagittal (Fp1-F3, F3-C3, C3-P3, P3-O1), R ParaS = right parasagittal (Fp2-F4, F4-C4, C4-P4, P4-O2), Vertex (Fz-Cz, Cz-Pz), Coronal = coronal ring (T1-T3, T3-C3, C3-Cz, Cz-C4, C4-T4, T4-T2, T2-T1), LFO = left FO (LFO1–2, LFO2–3, LFO3–4), RFO = right FO (RFO1–2, RFO2–3, RFO3–4). (E): Referential montage (C2 reference). L Hemi = left hemisphere (Fp1, F7, T1, T3, T5, F3, C3, P3, O1), Vertex (Fz, Cz, Pz), R Hemi = right hemisphere (Fp2, F8, T2, T4, T6, F4, C4, P4, O2), LFO = left FO (LFO1, LFO2, LFO3, LFO4), RFO = right FO (RFO1, RFO2, RFO3, RFO4). Contact 1 is deepest on FOs.

The second patient included in this study was a 58 year-old woman with no seizure history, initially evaluated for gradual cognitive decline, including repetitive questioning, misplacing objects, and social withdrawal. Within 5 years, she had severe dementia (additional clinical details are reported in the Supplementary Information). Brain MRI demonstrated diffuse atrophy (Supp. Figure 1c), and CSF showed an amyloid-tau index of 0.26 (<1.0 abnormal) and a phosphorylated tau level of 73.2 pg/mL (>61 abnormal), consistent with a diagnosis of early onset AD. There was no reported history of early onset dementia in this family (although genetic analysis was not obtained). At age 63, dramatic fluctuations in anxiety prompted further evaluation. Continuous video-EEG monitoring demonstrated rare multifocal epileptiform discharges seen independently over the right temporal, left temporal, and bifrontal regions (~2/hour during wakefulness and ~12/hour during sleep). Bilateral FO electrode recordings demonstrated frequent right mTL spikes (~16/hour during wakefulness and up to ~190/hour during sleep). Similar to the first patient, over 95% of the spikes detected on FO electrodes were not evident on scalp EEG (Figure 1d). Those that were evident on scalp EEG resembled benign epileptiform transients of sleep, previously defined as a normal variant of no pathological significance13 (Figure 1e). A trial of levetiracetam (1000mg/day) was not tolerated due to worsening mood.

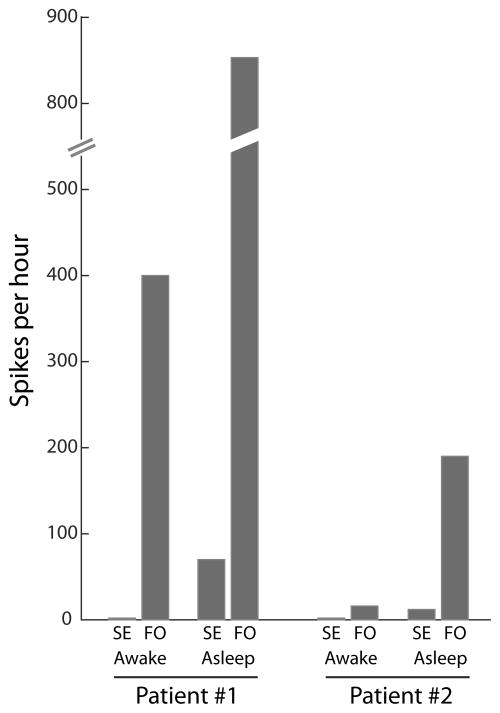

These two patients demonstrate that clinically silent mTL seizures and spikes can occur early in the course of AD, in the absence of significant scalp EEG abnormalities, and may predominate during sleep. Here, we validate a minimally invasive method to detect this activity using FO electrodes, which are safe, readily inserted percutaneously, and allow highly sensitive monitoring of mTL activity.9,14,15 The clinical utility of FO recordings in evaluating dementia patients is not yet known, though our FO recordings clearly demonstrate that scalp EEG findings greatly underestimate subcortical hyperexcitability in AD (Figure 2). All mTL seizures and over 95% of mTL spikes were not evident on scalp EEG. Additional studies of AD patients with FO recordings are needed to determine whether occult mTL epileptiform abnormalities are common or rare in AD and whether they define a hyperexcitable subtype of AD with specific treatment implications.

Figure 2.

mTL spikes detected on FO electrodes are absent from scalp EEG recordings. Quantification and comparison of spike frequencies simultaneously observed on scalp EEG (SE) and FO electrodes, during wakefulness and sleep, for Patient #1 and #2.

Our findings challenge the widely held view that epilepsy occurs only as a late sequela of neurodegeneration in AD, to be treated symptomatically once clinical seizures arise. Subclinical seizures and spikes can cause significant cognitive impairments16–18. Vossel and colleagues found subclinical scalp EEG and/or MEG epileptiform discharges in 42% of AD patients without a history of seizures, and patients with epileptiform discharges had a faster rate of cognitive decline19. In our patients, mTL seizures and spikes were activated during sleep, a period critical for memory consolidation, which may further increase their pathogenic impact20. Activation of spikes during sleep has been described in animal models21,22 and patients with AD19, and is common in focal epilepsies23. EEG recordings in the AD population should at minimum include sleep. When clinical seizures arise in AD, they are typically well-controlled with medication24,25, yet it remains unclear whether early detection and treatment of subclinical spikes and seizures can prevent or slow cognitive decline in AD. Elucidation of the cognitive impact of subclinical epileptiform activity on disease trajectory, and development of novel pharmacology to treat the specific hyperexcitability of the AD brain should be a critical priority.

Online Methods

Foramen ovale electrode placement

After explaining the risks and benefits of the procedure, consent for FO electrode placement was obtained from either the patient (Patient #1 had capacity to provide consent) or from the patient’s health care proxy (Patient #2). Placement of foramen ovale (FO) electrodes14 was performed in the operating room under sterile conditions, with the patient under general endotracheal anesthesia and positioned supine with neck extended and head turned away from the site of insertion. Prior to insertion, each cheek was prepped with chlorhexidine, and Lidocaine 1% was injected 2.5 cm lateral to the labial fissure. With the fluoroscope C-arm angled 45 degrees from vertical, the foramen ovale was visualized. A 16-gauge needle was initially used to pass through the skin, and a 10-gauge needle with stylet (Ad-Tech, Racine, WI) was advanced towards the foramen ovale under fluoroscopic guidance. The needle tip was placed approximately 2mm anterior to the clival line, and a lateral fluoroscopic image was taken to confirm the needle’s position. The stylet was then removed, and a four-contact FO electrode (Ad-Tech, Racine, WI) was advanced through the needle under fluoroscopic guidance so that all electrode contacts were positioned beyond the tip of the needle. A lateral fluoroscopic image was taken to confirm electrode position, and the needle was gently withdrawn. The electrode was sutured to the cheek with 0 silk sutures. The same procedure was repeated to place the FO electrode on the contralateral side. After placement of both FO electrodes, anteroposterior and lateral fluoroscopic images were taken to confirm final electrode position, and sterile dressings were placed over the electrode exit site on each cheek. The patient was awakened from general anesthesia and observed in the post-anesthesia recovery room for 1 hour. A post-procedure CT head was obtained, and the patient was brought to the inpatient Epilepsy Monitoring Unit for further monitoring. While FO electrodes were in place, the patient remained on vancomycin and ceftriaxone antimicrobial prophylaxis. At the end of the investigation, prophylactic anticoagulation was held for 24 hours, and the FO electrodes were removed at the bedside.

Scalp EEG and FO electrode recordings

Scalp electrodes were placed using the International 10–20 system with anterior temporal electrodes (T1, T2). All recordings were acquired using XLTEK hardware (Natus Medical Inc., Pleasanton CA) with data sampled at 1024 Hz. Scalp EEG and FO electrode recordings were visually interpreted as per routine clinical practice. Spike quantification was performed manually on randomly sampled, 30–60 minute segments of uninterrupted awake or asleep states.

Cognitive testing

The Blessed Information-Memory-Concentration test26 and Montreal Cognitive Assessment27 were administered by physicians and/or other trained personnel during Memory Disorders Unit and/or Epilepsy Clinic visits. CDR scales were assessed at each Memory Disorders Unit visit.

Laboratory testing

CSF amyloid and tau analysis was performed by Athena Diagnostics, Marlborough, MA (ADmark Alzheimer’s Evaluation).

Imaging

For patient #1, MRI brain images were obtained with and without gadolinium contrast, on a Siemens 3T Trio scanner, with the following sequences: sagittal FLAIR, sagittal T1, axial FLAIR, axial T2, coronal FLAIR, coronal T2, axial SWI, and axial DWI. 18FDG-PET images were obtained on a Siemens Biograph PET/CT scanner 45 minutes after injection with 5.5mCi of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose. For patient #2, 3T MRI brain images were obtained without contrast, with the following sequences: sagittal FLAIR, sagittal T1, axial FLAIR, axial T2, coronal T1, axial GRE, and axial DWI. All scans were performed for clinical purposes and interpreted by staff neuroradiologists.

Genetic Analysis

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects undergoing genetic analysis. Five of six siblings of Patient #1 were enrolled in an IRB approved neurogenetics project at Baylor College of Medicine (H-13798) with informed consent. As described previously28, DNA extracted from peripheral blood samples was submitted for whole exome sequencing (Genet, Gaithersburg, MD). Sequencing produced more than 120× average depth of coverage per exome (median coverage = 115) per sample with >90% of the captured bases at >20× coverage depth. Raw sequencing reads were processed using the Codified (https://www.scienceexchange.com/labs/codified-genomics) annotation platform29. Alleles with > 20× coverage and 40% allele fraction were considered for further analysis. The Similarity score (the proportion of the rare variants with MAF <0.5 shared among siblings was as expected, averaging 46% and ranging between 42% and 49%. We identified on average 707 total variants per exome (range 694–739) and an average of 131 variants per exome in known disease genes (range 124–138).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH-NINDS R25-NS065743 (A.D.L.), Massachusetts General Hospital Executive Committee on Research (A.D.L.), NIH-NINDS U01-NS090362 (A.G.), Citizens United for Research in Epilepsy (A.G.), NIH-NINDS R01-NS29709 (J.N.), and the Blue Bird Circle Foundation (J.N.).

Footnotes

Author Contributions: A.D.L, G.D., A.G., E.N.E., J.N., and A.J.C. drafted and edited the manuscript. A.D.L., G.D., and A.G. prepared the figures. A.D.L. performed the spike quantification. A.G. performed the genetic analysis. A.J.C. and J.N. conceived the study.

Competing Financial Interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Data Availability: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Alzheimer A. Über einen eigenartigen schweren Erkrankungsprozeβ der Hirnrinde. Neurol Cent. 1906;23:1129–36. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blocq P, Marinesco G. Sur les lesions et la pathogenie de l’epilepsie dite essentielle. La Sem Medicale. 1892;12:445–446. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noebels J. A perfect storm: Converging paths of epilepsy and Alzheimer’s dementia intersect in the hippocampal formation. Epilepsia. 2011;52:39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02909.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selkoe DJ, Hardy J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol Med. 2016;8:595–608. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201606210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aizenstein HJ, et al. Frequent amyloid deposition without significant cognitive impairment among the elderly. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:1509–17. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.11.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fjell AM, et al. Brain Changes in Older Adults at Very Low Risk for Alzheimer’s Disease. J Neurosci. 2013;33:8237–8242. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5506-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernhardt BC, et al. Mapping limbic network organization in temporal lobe epilepsy using morphometric correlations: insights on the relation between mesiotemporal connectivity and cortical atrophy. Neuroimage. 2008;42:515–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.04.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koliatsos VE, et al. Early involvement of small inhibitory cortical interneurons in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2006;112:147–62. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wieser HG, Elger CE, Stodieck SR. The ‘foramen ovale electrode’: a new recording method for the preoperative evaluation of patients suffering from mesio-basal temporal lobe epilepsy. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1985;61:314–322. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(85)91098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanchez PE, et al. Levetiracetam suppresses neuronal network dysfunction and reverses synaptic and cognitive deficits in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:E2895–E2903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121081109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bakker A, et al. Reduction of hippocampal hyperactivity improves cognition in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neuron. 2012;74:467–474. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lynch BA, et al. The synaptic vesicle protein SV2A is the binding site for the antiepileptic drug levetiracetam. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2004;101:9861–9866. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308208101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.White JC, Langston JW, Pedley TA. Benign epileptiform transients of sleep. Clarification of the small sharp spike controversy. Neurology. 1977;27:1061–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.27.11.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheth SA, et al. Utility of foramen ovale electrodes in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2014;55:713–724. doi: 10.1111/epi.12571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pastor J, Sola RG, Hernando-Requejo V, Navarrete EG, Pulido P. Morbidity associated with the use of foramen ovale electrodes. Epilepsia. 2008;49:464–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kleen JK, et al. Hippocampal interictal epileptiform activity disrupts cognition in humans. Neurology. 2013;81:18–24. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318297ee50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Binnie CD. Cognitive impairment during epileptiform discharges: Is it ever justifiable to treat the EEG? Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:725–730. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00584-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tatum WO, Ross J, Cole AJ. Epileptic pseudodementia. Neurology. 1998;50:1472–1475. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.5.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vossel KA, et al. Incidence and impact of subclinical epileptiform activity in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2016:1–13. doi: 10.1002/ana.24794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mander BA, Winer JR, Jagust WJ, Walker MP. Sleep: A Novel Mechanistic Pathway, Biomarker, and Treatment Target in the Pathology of Alzheimer’s Disease? Trends Neurosci. 2016;39:552–66. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Born HA, et al. Genetic suppression of transgenic APP rescues Hypersynchronous network activity in a mouse model of Alzeimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2014;34:3826–3840. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5171-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kam K, Duffy ÁM, Moretto J, LaFrancois JJ, Scharfman HE. Interictal spikes during sleep are an early defect in the Tg2576 mouse model of β-amyloid neuropathology. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20119. doi: 10.1038/srep20119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malow BA, Lin X, Kushwaha R, Aldrich MS. Interictal spiking increases with sleep depth in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1998;39:1309–1316. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rao SC, Dove G, Cascino GD, Petersen RC. Recurrent seizures in patients with dementia: frequency, seizure types, and treatment outcome. Epilepsy Behav. 2009;14:118–120. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarkis RA, Dickerson BC, Cole AJ, Chemali ZN. Clinical and Neurophysiologic Characteristics of Unprovoked Seizures in Patients Diagnosed With Dementia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;28:56–61. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.15060143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blessed G, Tomlinson BE, Roth M. The association between quantitative measures of dementia and of senile change in the cerebral grey matter of elderly subjects. Br J Psychiatry. 1968;114:797–811. doi: 10.1192/bjp.114.512.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nasreddine ZS, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klassen T, et al. Exome sequencing of ion channel genes reveals complex profiles confounding personal risk assessment in epilepsy. Cell. 2011;145:1036–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reid JG, et al. Launching genomics into the cloud: deployment of Mercury, a next generation sequence analysis pipeline. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-15-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.