Abstract

Background/Objectives

Although several studies have reported associations between moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA), body fatness, and visceral adipose tissue (VAT), the extent to which associations differ among Latinos and non-Latinos remains unclear. The present study evaluated the associations between body composition and MVPA in Latino and non-Latino adults.

Subjects/Methods

An exploratory, cross-sectional analysis was conducted using baseline data collected from 298 overweight adults enrolled in a 12-month randomized controlled trial that tested the efficacy of text messaging to improve weight loss. MVPA, body fatness and VAT were assessed by waist-worn accelerometry, DXA, and DXA-derived software (GE CoreScan GE, Madison, WI) respectively. Participants with less than 5 days of accelerometry data or missing DXA data were excluded; 236 participants had complete data. Multivariable linear regression assessed associations between body composition and MVPA per day, defined as time in MVPA, bouts of MVPA (time per bout ≥10 min), non-bouts of MVPA (time per bout <10 min), and meeting the 150-minute MVPA guideline. The modifying influence of ethnicity was modeled with a multiplicative interaction term.

Results

The interaction between ethnicity and MVPA in predicting percent body fat was significant (p = 0.01, 95% CI [0.58, 4.43]) such that a given increase in MVPA was associated with a greater decline in total body fat in non-Latinos compared to Latinos (adjusted for age, sex and accelerometer wear time). There was no interaction between ethnicity and MVPA in predicting VAT (g) (p = 0.78, 95% CI [−205.74, 273.17]) and BMI (p = 0.18, 95% CI [−0.49, 2.26]).

Conclusions

An increase in MVPA was associated with a larger decrease in body fat, but neither BMI nor VAT, in non-Latinos compared to Latinos. This suggests that changes in VAT and BMI in response to MVPA may be less influenced by ethnicity than is total body fatness.

Introduction

Obesity remains a substantial problem in the United States with approximately 35% of American adults classified as obese (Body Mass Index (BMI) > 30 kg/m2) in 2011–2012 9 (ref. 1). Obese individuals are at a higher risk of developing an array of health problems including hypertension, atherosclerosis, Type 2 diabetes, and cancer (ref. 2,3). Although BMI is frequently used in clinical settings to establish risk status, there is variation in individual risk of developing cardiometabolic disease at any given BMI (ref. 2). Recent evidence strongly suggests that the factor mediating the association between obesity and health outcomes is the amount of visceral adipose tissue (VAT) rather than the amount of either subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) or total body fat (ref. 2). VAT accumulation is strongly associated with unfavorable lipid profiles, insulin resistance, elevated diastolic BP (ref. 4), arterial stiffness, and overall poor cardiovascular health (ref. 5). In addition, analyses of interventions that increase physical activity and restrict caloric intake show that reductions in VAT, not SAT, mediate improvement in cardiometabolic risk factors such as triglyceride levels, cardiorespiratory fitness (ref. 6), HDL (ref. 7), and insulin sensitivity (ref. 8).

Numerous randomized controlled trials provide evidence for a beneficial effect of physical activity (PA) on VAT, particularly those involving aerobic PA interventions (ref. 7–13). These studies, however, have been limited primarily to Caucasian participants, with limited data on other racial/ethnic groups. The association between PA, VAT, cardiometabolic disease and overall mortality may differ by ethnicity. In a multi-ethnic cross-sectional analysis, the inverse association between self-report PA and VAT was significantly stronger for Filipinas than for white and black women (ref. 14). In addition, Lesser and colleagues (ref. 15) demonstrated that while both self-reported MVPA and VPA were associated with VAT in Chinese and European subjects, only VPA was associated with VAT in South East Asians. Furthermore, some studies suggest that the association between PA and diabetes is stronger for White Americans than for African Americans, Hispanics or Asian Pacific Islanders (ref. 16).

To our knowledge, there are no studies comparing the association between objective measures of PA and VAT among Latino and non-Latino adults. While research suggests that PA reduces BMI and total body fat in Latinos (ref. 17–20), data regarding VAT are sparse. Given the higher prevalence of obesity among Latinos (42.5%) compared to whites (32.6%), and the significant increase in the prevalence of obesity among Latinos from 1999–2010 (ref. 21), it is particularly important to investigate the extent to which PA may influence changes in VAT in this population.

In the present study, we evaluated the association between objectively measured PA and body composition derived from anthropometry and DXA among overweight or obese Latino and Non-Latino adults. Given their established influence on body composition, both age and sex were taken into account in the analyses (ref. 22). Although the World Health Organization (WHO) currently recommends 150 minutes of moderate or 75 minutes of vigorous physical activity per week accumulated in bouts lasting at least 10 minutes for the prevention of non-communicable disease and optimal health (ref. 23), decreases in VAT, BMI, and waist circumference have been reported for PA bouts lasting less than ten minutes (ref. 24– 27). Thus, we also explored if PA performed in very short bouts (i.e. less than 10 minutes) was associated with body composition in this sample.

Methods

Study Sample

Baseline data were analyzed from 298 overweight/obese adults enrolled in a 12-month randomized controlled trial that tested the efficacy of text messaging to improve weight-related outcomes (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01171586). Participants were recruited from San Diego and were required to be 21–61 years old, moderately overweight or obese (BMI > 27–39.8), own a cell phone capable of sending and receiving automated text messages, not taking medications that could cause weight gain, and have no history of eating disorders or weight loss surgery. In the present study, participants with fewer than 5 days of accelerometry-based PA data or missing baseline DXA data were excluded from analysis, leaving 236 participants (96 Latino, 140 non-Latino). Inclusion/exclusion criteria were pre-established. Those excluded did not differ on the basis of sex, ethnicity or BMI, but were younger than those included (mean ageexcluded= 38.94, ± 10.74 yr; vs. Mean ageincluded = 42.64 ±10.72 yr; p = 0.016, 2-sided). This study was approved by the University of California, San Diego, Institutional Review Board (Project # 091040) and all participants provided written informed consent.

Measurement Methods

Objective physical activity levels were measured using waist-worn ActiGraph GT1M and/or GT3X+ accelerometers (ActiGraph, LLC; Pensacola, FL). Participants were asked to wear the ActiGraph for at least seven days and were prompted twice via telephone during the monitoring period to assist with compliance. A valid day consisted of > 10 hours of wear time. Data were collected as counts at 30-second epochs. MVPA and VPA were defined using the Troiano count thresholds of 2020 and 5999 counts/minute respectively (ref. 28). A bout consisted of MVPA lasting ≥ 10 minutes allowing for an interruption of up to 2 minutes anywhere within the bout. All accelerometer data extraction, processing, and scoring was performed using the most up-to-date version of ActiLife software.

Body weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a calibrated digital scale, and height (without shoes) was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a stadiometer. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from height and weight as kg/m2. To assess body fat and VAT, participants underwent full body DXA scans conducted by an experienced technician certified by the state of California. The use of DXA and CoreScan/enCORE Software (GE/Lunar, Madison, WI) has been recently validated for assessing VAT, and was reported to correlate strongly to expert readings of CT-derived VAT in both men and women across a wide range of ages and BMIs (ref. 29,30). Regions of interest were automatically determined by the software and adjusted as needed by a trained technician, then verified by a study investigator with experience in DXA-derived body composition. Body fatness was expressed as the percentage of fat mass relative to total body mass; VAT was expressed in grams.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics (proportions, means, and standard deviations) were used to describe the demographic characteristics. Multivariable linear regression assessed associations between body composition (BMI, percent body fat, VAT) and multiple measures of MVPA adjusting for sex, age, ethnicity (Latino or Non-Latino) and ActiGraph wear time. MVPA outcome variables of interest included: (1) Average minutes of MVPA per day (MVPA), (2) Average minutes of MVPA performed in bouts of ≥10 minutes per day (MVPA bouts), (3) Average minutes of MVPA performed in < 10 minute bouts (non-bouts MVPA), and (4) a yes/no binary determined upon performing at least 150 minutes of MVPA in bouts of ≥10 minutes (Meeting Guidelines). Residuals from each model with a continuous MVPA variable were plotted. The assumption of homoscedasticity was met for each model. The modifying influences of sex, age and ethnicity in the relationship between total MVPA and body composition were modeled independently with multiplicative interaction terms. For the interaction analyses, age was entered as a binary variable after creating a median split at 43 years. For the multivariate adjusted models, means and coefficients were reported with their associated standard error terms. Associations and interactions were considered significant if p ≤ 0.05. Given the exploratory nature of this analysis, additional adjustments were not made for multiple comparisons. All analyses were performed using Stata 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Descriptive Statistics of the Total Sample

Participants were predominantly female (78%), educated and employed with an average age of 43 years. Forty-one percent of the sample was Latino (Table 1). The sample mean BMI, percent body fat, and VAT mass was 32.6 kg/m2, 43.1% and 1.3 kg, respectively. On average, participants performed 25 minutes of MVPA per day of which approximately two-thirds were not completed in bouts.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Demographics | n = 236 |

|---|---|

| Age (SD) | 42.64 (10.72) |

| Female (%) | 77.97 |

| Latino (%) | 40.68 |

| Education (%) | |

| High School or Less | 19.92 |

| Some College/Associate/Technical | 33.47 |

| College Degree | 22.03 |

| Graduate or Professional Degree | 24.58 |

| Employment Status (%) | |

| Unemployed | 20.34 |

| Part-Time | 18.22 |

| Full-Time | 61.44 |

| Physical Activity (min/day) (SD) | |

| MVPA | 25.10 (17.13) |

| MVPA Bouts | 9.13 (11.01) |

| MVPA Non-Bouts | 15.97 (10.79) |

| Percent Meeting 150 Minute Guideline | 44.07 |

| Body Composition (SD) | |

| BMI (kg/msq) | 32.55 (3.4) |

| Body Fat (%) | 43.11 (5.79) |

| VAT (kg) | 1.27 (0.62) |

Body Composition

The average BMI, percent body fat and VAT for each sex, ethnicity and age group obtained from the regression models are shown in Table 2. On average, women had lower BMI, higher percent body fat, and lower VAT than did men; older individuals had higher BMI, percent body fat, and VAT than did younger individuals. The differences in body composition between Latinos and non-Latinos were small, with Latinos evidencing slightly higher BMI (32.59 m/kg2 vs. 31.15 m/kg2), lower percent body fat (47.42% vs. 48.15%), and higher VAT (838.68 g vs 631.08 g) than non-Latinos. Variance between comparison groups was similar.

Table 2.

Multivariable Adjusted* Mean (SE) Body Composition

| Sex | Ethnicity | Age | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Latino | Non-Latino | ≤43 | >43 | |

| n | 52 | 184 | 96 | 140 | 120 | 116 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 32.98 (−2.72) | 31.74 (−2.64) | 32.59 (−2.65) | 32.15 (−2.66) | 31.08 (−2.56) | 32.56 (−2.66) |

| % Body Fat | 40.03 (−3.4) | 47.65 (−3.31) | 47.42 (−3.28) | 48.15 (−3.24) | 47.47 (−3.19) | 49.8 (−3.32) |

| VAT (g) | 1355.63 (−417.55) | 603.2 (−405.94) | 838.68 (−408.14) | 631.08 (−402.38) | 1322.5 (−390.92) | 1902.71 (−406.51) |

Adjusted for sex, ethnicity, age and minutes of Acti-graph wear time.

Associations between MVPA and Body Composition

Table 3 shows the associations between each MVPA variable and body composition variables controlling for sex, age, ethnicity and accelerometer wear-time. All measures of MVPA were significantly and negatively associated with percent body fat (p<0.05). A 30-minute daily increase in MVPA was associated with a 2% average decrease in body fat. The associations between MVPA and BMI were significant for non-bouts MVPA and approached significance for total MVPA. For every 30-minute increase in non-bouts MVPA, BMI decreased by 1.5 kg/m2. Similarly, the associations between PA and VAT were significant only for MVPA and non-bouts MVPA. Every 30-minute increase in MVPA and non-bouts MVPA were associated with a 123g and 249g decrease in VAT respectively.

Table 3.

Multivariable Adjusted* Association between PA and Body Composition

| Coefficient | SE | 95% CI | p-value | Rsq for Model | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | |||||

| MVPA | −0.77 | 0.4 | (−1.56, 0.02) | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| MVPA Bouts | −0.53 | 0.6 | (−1.72, 0.66) | 0.38 | 0.03 |

| MVPA Non-Bouts | −1.45 | 0.66 | (−2.74, −0.16) | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Meet 150 | −11.44 | 13.4 | (−37.85, 14.96) | 0.39 | 0.03 |

| Percent Body Fat | |||||

| MVPA | −1.96 | 0.5 | (−2.94, −0.97) | 0 | 0.48 |

| MVPA Bouts | −2.11 | 0.76 | (−3.61, −0.60) | 0.01 | 0.46 |

| MVPA Non-Bouts | −2.79 | 0.83 | (−4.42, −1.15) | 0 | 0.47 |

| Meet 150 | −1.4 | 0.57 | (−2.51, −0.28) | 0.01 | 0.46 |

| VAT (g) | |||||

| MVPA | −123.06 | 61.28 | (−243.80, −2.33) | 0.05 | 0.32 |

| MVPA Bouts | −70.37 | 92.87 | (−253.36, 112.62) | 0.45 | 0.31 |

| MVPA Non-Bouts | −249.42 | 100.46 | (−447.35, −51.49) | 0.01 | 0.33 |

| Meet 150 | −105.38 | 68.31 | (−239.98, 29.21) | 0.12 | 0.32 |

Adjusted for sex, ethnicity, age and minutes of Acti-graph wear time. The coefficient is the average change in body composition per 30-minute/day increase in PA

Interactions by Age, Sex, and Ethnicity

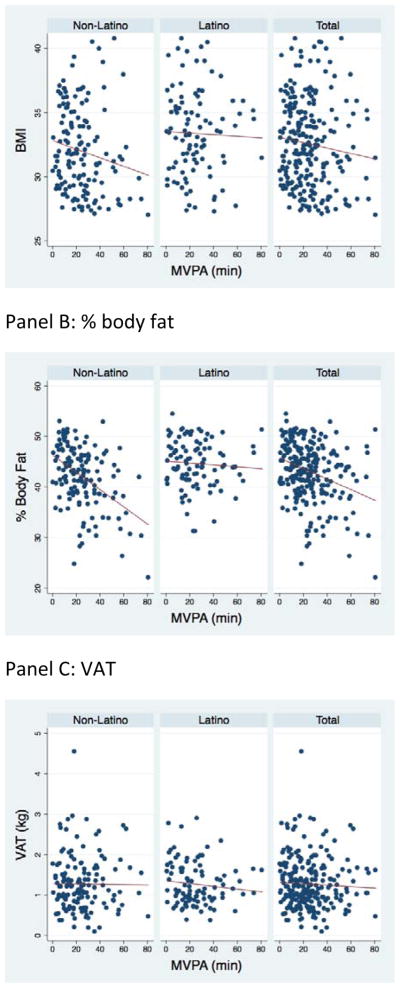

There was a significant interaction between ethnicity and MVPA in predicting percent body fat such that a given increase in MVPA was associated with a greater decline in body fat in non-Latinos. There was no interaction between ethnicity and MVPA in predicting VAT or BMI (Table 4). Figure 1 shows the unadjusted regression models for BMI, percent body fat and VAT vs. MVPA for Latinos and non-Latinos.

Table 4.

Multivariable adjusted* interactions between MVPA and covariates in predicting body composition

| Coefficient | SE | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| Sex Interaction | −0.85 | 0.87 | (−2.57, 0.87) | 0.33 |

| Male | −1.38 | 0.75 | (−2.85, 0.09) | |

| Female | −0.53 | 0.47 | (−1.45, 0.39) | |

|

| ||||

| Ethnicity Interaction | 1.07 | 0.79 | (−0.49, 2.62) | 0.18 |

| Latino | −0.19 | 0.58 | (−1.34, 0.95) | |

| Non-Latino | −1.26 | 0.54 | (−2.33, −0.20) | |

|

| ||||

| Age Interaction | −1.62 | 0.78 | (−3.16, −0.09) | 0.04* |

| ≤43 | 0.23 | 0.61 | (−0.98, 1.43) | |

| > 43 | −1.39 | 0.51 | (−2.39, −0.40) | |

|

| ||||

| % Body Fat | ||||

| Sex Interaction | −0.86 | 1.09 | (−3.01, 1.30) | 0.43 |

| Male | −2.58 | 0.93 | (−4.42, −0.74) | |

| Female | −1.72 | 0.59 | (−2.88, −0.57) | |

|

| ||||

| Ethnicity Interaction | 2.51 | 0.98 | (0.58, 4.43) | 0.01* |

| Latino | −0.61 | 0.72 | (−2.03, 0.81) | |

| Non-Latino | −3.12 | 0.67 | (−4.44, −1.80) | |

|

| ||||

| Age Interaction | −2.09 | 0.97 | (−4.00, −0.17) | 0.03* |

| ≤43 | −0.71 | 0.76 | (−2.21, 0.79) | |

| > 43 | −2.8 | 0.63 | (−4.04, −1.55) | |

|

| ||||

| VAT (g) | ||||

| Sex Interaction | −63.08 | 134.02 | (−327.15, 201.00) | 0.64 |

| Male | −168.56 | 114.52 | (−394.21, 57.08) | |

| Female | −105.49 | 71.85 | (−247.05, 36.08) | |

|

| ||||

| Ethnicity Interaction | 33.71 | 121.53 | (−205.74, 273.17) | 0.78 |

| Latino | −104.94 | 89.66 | (−281.60, 71.73) | |

| Non-Latino | −138.65 | 83.23 | (−302.65, 25.35) | |

|

| ||||

| Age Interaction | −113.09 | 118.9 | (−347.36, 121.18) | 0.34 |

| ≤43 | −82.29 | 93.09 | (−265.71, 101.12) | |

| > 43 | −195.38 | 77.31 | (−347.71, −43.06) | |

Adjusted age, sex and accelerometer wear time

Figure 1.

Unadjusted Body Composition vs MVPA by Ethnicity

Panel A: BMI

Panel B: % body fat

Panel C: VAT

There was a significant interaction between age and MVPA in predicting BMI and body fat such that a given increase in MVPA was associated with a larger decrease in BMI and body fat in older individuals. There were no interactions between sex and MVPA in predicting any of the body composition variables (Table 4).

Discussion

The primary aims of this study were to investigate the relationship between PA and body composition in a sample consisting of approximately half Latino adults, and to compare this relationship between Latinos and non-Latinos. In the entire sample, MVPA was negatively associated with BMI, percent body fat and VAT. Meeting 150 minute bout guidelines was associated with lower body fat, but was not significantly associated with lower BMI or VAT. In general, the associations between non-bouts of MVPA and body composition were stronger than the associations between MVPA completed in bouts of ≥ 10 minutes. These results may be partially explained by the fact that approximately two-thirds of the total MVPA accumulated by participants was in bouts lasting less than 10 minutes. Nonetheless, these results support previous literature suggesting that accumulating MVPA in short bouts is associated with lower BMI, less total body fat and VAT (ref. 24 –27).

The inverse relationship between MVPA and percent body fat was stronger for non-Latinos than for Latinos. These findings support literature suggesting that the relationship between PA and body composition may differ by race or ethnicity (ref. 15,16). However, research in Latinos is limited especially regarding VAT. A variety of factors could explain this finding such as differences in lifestyle, SES, diet and eating habits, rates of fat oxidation during exercise (ref. 14–16), and regional fat distribution. Several studies demonstrate that at a given BMI, the amount and distribution of body fat tends to differ by ethnicity. For example, at a BMI < 30 kg/m2, Latin American women tend to have more body fat than European American and African American women, while at a BMI > 35 kg/m2, European American women tend to have more body fat than the other groups (ref. 31). Other work has shown that at a given BMI, Latinos tend to have more trunk fat (ref. 32) and VAT volume measured by CT (ref. 33), and that Latino men tend to accumulate more VAT for a given increase in BMI (ref. 33). The present study found that when controlling for sex, age, and physical activity, Latinos tend to have less total percent body fat, but more VAT, suggesting that Latinos have greater VAT relative to total percent body fat. Supporting this conclusion, Carroll et al. showed that Latinas have a higher L4L5 VAT to subcutaneous fat ratio than do White women (ref. 33). However, to our knowledge, no other studies have directly compared total percent body fat and total VAT between Latinos and non-Latinos while controlling for physical activity.

Interestingly, the relationship between MVPA and body composition did not differ between Latinos and non-Latinos for VAT or BMI. These results suggest that changes in VAT and BMI in response to MVPA may be less influenced by ethnicity than is total body fatness. Although a causal relationship cannot be inferred due to the correlational nature of this analysis, if true, it would have important implications for weight loss management and counseling across ethnicities. For example, for a given change in MVPA, Latinos may notice less change in total body fat compared to their non-Latino counterparts, but may be experiencing similar health benefits due to declining VAT.

Interactions were also found between age and PA and their association with body composition such that for a given increase in MVPA, the decreases in BMI and percent body fat were greater for older individuals. This implies that older individuals may require a lower amount of PA to obtain similar benefits in maintaining a healthy BMI and body fatness compared to younger adults.

Strengths of this study included a large proportion of Latino adults, the collection of objective PA data by accelerometry, and the use of validated DXA software to assess total body fat and VAT. To our knowledge, it is also the first head-to-head comparison of the association between MVPA and body composition in Latino and non-Latino adults. Limitations included the disproportionately small number of men and the correlational nature of the analyses. We also did not differentiate between weekend or weekday accumulation of MVPA. Although patterns of physical activity may influence body composition and mortality (ref. 34), our goal in the present study was to investigate the relationship between body composition and total bout accumulation regardless of when or how the bouts were accumulated. Finally, multiple measures of physical activity were used and p-values were unadjusted for multiple testing, increasing the likelihood of Type I error. Thus, longitudinal studies with precise measurement of PA and body composition and large sample sizes are needed to clarify the interactions between ethnicity and PA in predicting body composition.

In conclusion, this study found that a given increase in MVPA was associated with a larger decrease in percent body fat in non-Latinos than in Latinos. The relationship of MVPA with VAT and BMI, however, did not differ by ethnicity. Future work is needed to verify these relationships and link these outcomes to cardiovascular and metabolic disease risk.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health, Grant 5T35HL007491. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01171586

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Despres J-P. Body Fat Distribution and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: An Update. Circulation. 2012;126(10):1301–1313. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.067264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neeland IJ, Turer AT, Ayers CR, Berry JD, Rohatgi A, Das SR, et al. Body Fat Distribution and Incident Cardiovascular Disease in Obese Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(19):2150–2151. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.01.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosch Ta, Dengel DR, Kelly aS, Sinaiko aR, Moran a, Steinberger J. Visceral adipose tissue measured by DXA correlates with measurement by CT and is associated with cardiometabolic risk factors in children. Pediatr Obes. 2014;(August 2015):1–8. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strasser B, Arvandi M, Pasha EP, Haley AP, Stanforth P, Tanaka H. Abdominal obesity is associated with arterial stiffness in middle-aged adults. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;25(5):495–502. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borel AL, Nazare JA, Smith J, Almeras N, Tremblay A, Bergeron J, et al. Visceral and not subcutaneous abdominal adiposity reduction drives the benefits of a 1-year lifestyle modification program. Obes (Silver Spring) 2012;20(6):1223–1233. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.396. oby2011396 [pii]\r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas EL, Brynes E, McCarthy J, Goldstone P, Hajnal JV, Saeed N, et al. Preferential loss of visceral fat following aerobic exercise, measured by magnetic resonance imaging. Lipids. 2000;35(7):769–776. doi: 10.1007/s11745-000-0584-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slentz CA, Aiken LB, Houmard JA, Bales CW, Johnson JL, Tanner CJ, et al. Role of Exercise in Reducing the Risk of Diabetes and Obesity Inactivity, exercise, and visceral fat. STRRIDE: a randomized, controlled study of exercise intensity and amount. Jounral of Applied Physioogy. 2005;27710:1613–1618. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00124.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herzig K-H, Ahola R, Leppäluoto J, Jokelainen J, Jämsä T, Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi S. Light physical activity determined by a motion sensor decreases insulin resistance, improves lipid homeostasis and reduces visceral fat in high-risk subjects: PreDiabEx study RCT. Int J Obes. 2014;38(8):1089–1096. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2013.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heydari M, Freund J, Boutcher SH. The effect of high-intensity intermittent exercise on body composition of overweight young males. J Obes. 2012;2012:480467. doi: 10.1155/2012/480467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irving B, Davis CK, Brock DW, Weltman Y, Swift D, Barrett EJ, et al. Effect of exercise training on abdominal visceral fat and body composition. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(11):1863–1872. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181801d40.Effect. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ismail I, Keating SE, Baker MK, Johnson NA. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of aerobic vs. resistance exercise training on visceral fat. Obes Rev. 2012;13(1):68–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vissers D, Hens W, Taeymans J, Baeyens J-P, Poortmans J, Van Gaal L. The Effect of Exercise on Visceral Adipose Tissue in Overweight Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56415. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larsen BA, Allison MA, Kang E, Saad S, Laughlin GA, Araneta MRG, et al. Associations of physical activity and sedentary behavior with regional fat deposition. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46(3):520–528. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182a77220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lesser Ia, Yew AC, Mackey DC, Lear Sa. A Cross-Sectional Analysis of the Association between Physical Activity and Visceral Adipose Tissue Accumulation in a Multiethnic Cohort. J Obes. 2012;2012:703941. doi: 10.1155/2012/703941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gill JMR, Celis-Morales CA, Ghouri N. Physical activity, ethnicity and cardio-metabolic health: Does one size fit all? Atherosclerosis. 2014;232(2):319–333. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brill JB, Perry AC, Parker L, Robinson A, Burnett K. Dose – response effect of walking exercise on weight loss. How much is enough? Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002:1484–1493. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Byrd-Williams CE, Belcher BR, Spruijt-Metz D, Davis JN, Ventura EE, Kelly L, et al. Increased physical activity and reduced adiposity in overweight Hispanic adolescents. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(3):478–484. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181b9c45b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keller C, Treviño RP. Effects of two frequencies of walking on cardiovascular risk factor reduction in Mexican American women. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24(5):390–401. doi: 10.1002/nur.1039. [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vella CA, Ontiveros D, Zubia RY, Dalleck L. Physical activity recommendations and cardiovascular disease risk factors in young Hispanic women. Journal of Sports Science. 2011;29(1):37–45. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2010.520727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution or body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):491–497. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kenney L, Wilmore J, Costill D. Physiology of Sport and Exercise. 6. Champaign: Human Kinetics Publishers; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oja P, Titze S. Physical activity recommendations for public health: development and policy context. EPMA J. 2011;2(3):253–259. doi: 10.1007/s13167-011-0090-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ayabe M, Kumahara H, Morimura K, Sakane N, Ishii K, Tanaka H. Accumulation of short bouts of non-exercise daily physical activity is associated with lower visceral fat in Japanese female adults. Int J Sports Med. 2013;34(1):62–67. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1314814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fan JX, Brown BB, Hanson H, Kowaleski-Jones L, Smith KR, Zick CD. Moderate to vigorous physical activity and weight outcomes: Does every minute count? Am J Heal Promot. 2013;28(1):41–49. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.120606-QUAL-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGuire KA, Ross R. Incidental Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior Are Not Associated With Abdominal Adipose Tissue in Inactive Adults. Obesity. 2012;20(3):576–582. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strath SJ, Holleman RG, Ronis DL, Swartz AM, Richardson CR. Objective physical activity accumulation in bouts and nonbouts and relation to markers of obesity in US adults. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5(4):A131. A131[pii] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Masse LC, Tilert T, Mcdowell M. Physical Activity in the United States Measured by Accelerometer. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2007:181–188. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaul S, Rothney MP, Peters DM, Wacker WK, Davis CE, Shapiro MD, et al. Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry for Quantification of Visceral Fat. Obesity. 2012;20(6):1313–1318. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Micklesfield LK, Goedecke JH, Punyanitya M, Wilson KE, Kelly TL. Dual-Energy X-Ray Performs as Well as Clinical Computed Tomography for the Measurement of Visceral Fat. Obesity. 2012;20(5):1109–1114. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fernández JR, Heo M, Heymsfield SB, Pierson RN, Pi-Sunyer FX, Wang WM, et al. Is percentage body fat differentially related to body mass index in Hispanic Americans, African Americans, and European Americans? Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77(1):71–75. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rahman M, Temple JR, Breitkopf CR, Berenson AB. Racial differences in body fat distribution among reproductive aged women. Metabolism. 2009;58(9):1329–1337. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.04.017.Racial. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carroll JF, Chiapa AL, Rodriquez M, Phelps DR, Cardarelli KM, Vishwanatha JK. Visceral fat, waist circumference, and BMI: impact of race/ethnicity. Obes (Silver Spring) 2008;16(3):600–607. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.92oby200792. [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee I, Sesso HD, Ogumo Y, Paffenbarger RS. The “Weekend Warrior” and Risk of Mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(7):636–641. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]