Introduction

Increased attention to addressing health disparities in the U.S. has necessitated the development of community-engaged interventions and research strategies to alleviate the disproportionate burden of illness faced by minorities and other vulnerable groups.1 Community-based participatory research (CBPR) has gained prominence in recent decades as a promising approach to addressing these health disparities and involves engaging members of the community as equal partners in the research process.2 This approach is increasingly being promoted through funding agencies. For example, the National Institute for Nursing Research (NINR) identifies CBPR in their strategic plan and provides funding mechanisms to support community partnerships for the purposes of advancing nursing research.3, 4 Additionally, after the passing of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) was established. Unlike previous research funding agencies, PCORI requires that patients, caregivers, and other key stakeholders become actively engaged as members of the research team and are seen as equal contributors to the research process.5 These advances are well aligned with nursing’s strong tradition of engaging individuals, families, and communities in designing and evaluating nursing care.6, 7

Community Advisory Boards (CABs) are frequently used to facilitate community-engaged research. CABs are commonly developed within academic-community partnerships to provide a mechanism for representatives from the community of interest, identify priorities, and inform the research process. Research evaluating the effectiveness of CABs has highlighted the important contributions they make in establishing trust and mutually beneficial relationships between academics and community members.8 Although best practices in working with CABs during the formation, operation, and maintenance phases have been described,8 key elements of CABs contributing to the success of diverse academic-community research teams remain largely undescribed in nursing research. The purpose of this paper is to provide a framework for effectively working with CABs in community-engaged research. This framework is informed by research evidence identifying key components of community-engaged research that produces positive health outcomes and experiences of Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) Nurse Faculty Scholars (NFS) working with CABs in diverse communities.

Nurse Faculty Scholars’ Partnerships with CABs

The RWJF NFS program supported early career nurse faculty with diverse research interests. Scholars working in community-based settings or developing interventions were encouraged by their mentors and peers to consider incorporating CABs into their research design as a means of strengthening the quality and impact of their work. CABs were especially promoted for the scholars who were working with vulnerable populations such as racial and ethnic minority groups (e.g., African American, American Indian, Hispanic/Latino), underserved geographical regions in the U.S. (e.g., inner city and rural communities), and representatives from different sectors of society (e.g., healthcare, education, religion) that have traditionally not been included in research as partners. While many of the NFS had been collaborating with CABs for many years, others began to formulate collaborative relationships with members of their targeted groups and others stakeholders as part of their RWJF funded research projects. The RWJF NFS provided support for these research efforts by providing mentorship, funding, and professional development opportunities for scholars interested in growing as community-engaged nurse scientists.

Conceptual Framework

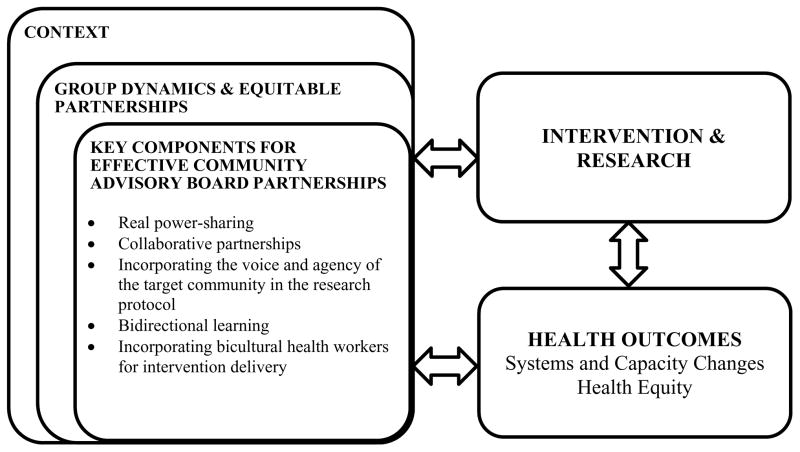

Various conceptual frameworks for community-engagement have been proposed. One of the most widely adopted approaches is the CBPR Model described by Wallerstein and colleagues.9 There are four main constructs in this model – context, group dynamics, interventions and research, and outcomes. Context includes social, environmental, and cultural factors that may influence risk and protective factors for health outcomes in communities. The construct of group dynamics addresses how research is conducted to create equitable partnerships. Interventions and research consist of the main variable(s) leading to the health outcomes influenced by context and group dynamics. Finally, outcomes include the results of the intervention on various levels, including system, capacity, health, and health equity outcomes.

Researchers have recently begun to evaluate community-engagement strategies employed by researchers. This is important given that these strategies, although often well-intended, can have unintended negative consequences on the community such as burden, exhaustion, and disappointment.10 Recently Cyril and colleagues conducted a systematic review to address the gap in knowledge regarding the methods and components of CBPR that maximize positive health outcomes among vulnerable populations.11 Twenty-four studies that evaluated community-engaged methods were identified, and 21 (87.5%) documented positive effects on health outcomes. The key community-engaged components that had a positive impact on health outcomes included: (1) real power-sharing between academic and community partners, (2) collaborative partnerships, (3) incorporating the voice and agency of the target community in the research protocol, (4) bidirectional learning between community members and researchers, and (5) incorporating bicultural health workers that reflects the cultural identity of the community for intervention delivery. The community-engaged components that have been identified to improve the health of disadvantaged populations also resonate with input from the community regarding the importance of including trust development, capacity, mutual learning, and power dynamics as cross-cutting concepts of CBPR.12

Given the effectiveness of the five community-engaged components identified by Cyril and colleagues (2015), we have adapted the CBPR framework9 to highlight the importance of implementing these approaches when working with CABs in community-engaged nursing research (See Figure 1). In the subsequent section we review these key components and provide exemplars regarding how these were implemented through CABs researching a myriad of health issues across diverse communities.

Figure 1.

Key components for working effectively with community advisory boards in community-engaged nursing research.

Note: Adapted from: Wallerstein N, Oetzel J, Duran B, Tafoya G, Belone L, Rae R. (2008); Cyril, S, Smith, B.J., Possamai-Inesedy, A., and Renzaho, A. (2015).

Working with CABs in Diverse Communities

1. Incorporating Real Power-Sharing

Real power-sharing lies at the heart of community-engaged research and provides the cornerstone on which to build relationships advancing the health of communities. In recent years community-based approaches that incorporate power-sharing have been used to address concerns of communities in areas such as depression and stress,13 smoking cessation,14 diabetes,15 cancer,16 and HIV,17 among others. To identify the critical aspects of power-sharing in community-engaged research, consideration needs to be taken to how power is initiated, negotiated, balanced, and shared. In addition to methodology that strongly supports this model, and a movement towards Action Research18 (research with outcomes that improve community health), the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI)19–22 mandates that real power-sharing between researchers and patients (i.e., individuals, families and communities) be present from the time the research question is formulated, to the planning, conduct, and dissemination of findings.23 CABs can be a way to move towards a power-sharing structure by developing an organizational structure to help ensure shared decision making such as the establishment of memorandum of understanding for the partners, operating guidelines and bylaws for the CAB based on the principles of community-based and community engaged research.17 These agreements, guidelines and bylaws often outline the composition of the CAB (e.g., community members vs. academics), decision making authorities, compensation or other benefits for the members, delineate roles and responsibilities, provide guidance for authorship for publications and other products of the partnership, and articulate other issues of importance to the members of the CABs.24 It is not necessarily the documents alone that lead to power sharing, but the process of outlining the responsibilities of all parties in the both the research and in the improvement of health of communities, that does.

The Communities of Harlem Health Revival

In 2006, the Office of Minority Health of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene convened the Borough of Manhattan Ecumenical Advisory Group to advise and advocate for improving the health of Manhattan residents. In 2010 the group’s name was changed from Central Harlem Health Revival to Communities of Harlem Health Revival in order to be more inclusive of the changing demographics of Harlem from a primarily Black and African American community to one that was increasingly comprised of the Hispanic/Latino community. Central Harlem Health Revival first incorporated real power-sharing by engaging diverse stakeholders, especially community members, to work side by side to establish the mission, vision, goals, programs, and roles of partners. Each meeting was co-chaired by an academic and a community member, with community members and academics working together in interdependent roles of critical importance. For example, using models such as PRECEDE-PROCEED25, the community members and the researchers worked side-by-side, identifying and prioritizing community health issues defining desired outcomes, and designing implementation and dissemination strategies that would improve health overall.

2. Collaborative Partnerships

Collaborative partnerships between academics and community members must to be established in order for true power-sharing to exist. However, partnerships can vary based on their level of formality, the nature of their mission, and the delineation of roles. True collaboration is differentiated from other types of partnerships in that the relationships between entities are well defined, mutually beneficial, and advance a common goal.26 Given the influence of social determinants on health disparities, nurse researchers seeking to promote health equity must establish collaborative partnerships not only with healthcare agencies, but across sectors including: education, criminal justice system, public housing, faith-based organizations, community-based non-profit organizations, and other critical stakeholders. These cross-sector collaborative partnerships have been identified as a key strategy for health improvements by creating environmental system changes, facilitating community-wide behavioral changes, and improving population health outcomes.27 However, convening diverse stakeholders may be difficult given differences in their goals and involves negotiations across sectors and individuals. In order for these negotiations to be collaborative in nature, democratic and consensus decision making strategies should be used to ensure that diverse perspectives are considered and respected, especially among groups that have previously not been given voice in influencing the development of health strategies.27

The Center for Urban Youth and Families

The Center for Urban Youth and Families at Rutgers University School of Nursing (CUYF) is an interprofessional research center established in 2012 that aims to improve the health of children and families who reside in urban communities. Center fellows include academicians from nursing, medicine, dentistry, anthropology, social work, and criminal justice. CUYF has an all-volunteer CAB comprised of members of the university, local clergy, and representatives from community-based organizations. Center fellows are committed to using CABs for their studies whenever possible. A CUYF fellow who practiced in a school based health center was approached by family members of children with asthma with concerns regarding access to asthma specialty care. In response to this, the fellow convened a group comprised of university researchers, the clinic director, the clinic’s Chief Strategic Officer, the Associate Dean of Research, two clinic parents whose children had asthma and two adolescent patients with asthma. The group met and developed the concept of a community-based asthma specialty clinic. The parents and adolescent patients provided valuable input regarding what the clinic would like and how it would function. CUYF fellows and clinic administration understood the importance of measuring the effectiveness of the program to ensure sustainability so they agreed to make the project a research study. CUYF fellows consulted university statisticians during the project design and they recommended a design with randomization at the individual level, however CAB members strongly objected to randomization in this way. Although CAB members understood the concept of rigor and randomization, they perceived randomization at the individual level as being discriminatory and unfair to community members. In fact, CAB members told CUYF fellows they would not participate in the project if randomization occurred at the individual level. They felt it was unfair that children attending the same school and utilizing the clinic’s services would receive two different types of care. One parent stated, “The way this is set up my child could get different care than her cousin or maybe even her brother. That’s not right.” Because of this, the project stalled. CUYF fellows invited the statisticians to meet with the CAB members at one of the school based health centers. The statisticians were able to hear the passion and concerns of the community. The group worked together and an alternative design that used cluster randomization, was proposed..

3. Incorporating the Voice and Agency of Beneficiary Communities in Research Protocol

Incorporating voice into research refers to the dialogue between researchers and members of a community about meaningful topics that matter to them.28, 29 As researchers attempt to incorporate agency, they must listen to the voice of community members with the purpose of enacting a change based on the voice.30 The development of CABs is one way to engage the voice and agency of the targeted community in the research protocol. However, attention must be given to ensure that the members of the CAB truly represent the needs, strengths, and voices of the community of interest.24 As such, CABs also should work to engage the beneficiary communities in other ways such as holding focus groups, community forums, and providing other opportunities for voices to be heard and ensuring the research is responsive to these. Caution should be taken to ensure all members of the CABs have an opportunity to voice their perspectives and influence subsequent community actions.

The Workplace Violence Community Advisory Board

The Workplace Violence CAB was formed in 2013 in response to a reported need to engage victims of workplace violence in the development of a program.31 The purpose of the Workplace Violence CAB was to develop a multi-faceted workplace violence prevention program for emergency department settings. Incorporating voice and agency to the Workplace Violence CAB was purposeful. Previously, researchers found all employees, including those often marginalized (i.e., registration clerks), were at risk for workplace violence (e.g., verbal abuse, threats, physical assaults).32 As a result, the community members invited to participate on the Workplace Violence CAB were not limited to physicians and registered nurses, persons commonly perceived as having power in an emergency department setting, but also included staff from registration, unlicensed assistive personnel, police, and social workers from diverse emergency department settings. The members of the Workplace Violence CAB were divided into groups which were facilitated by a person who was trained to ensure equal voice among participants in discussing their experiences and recommendations for the prevention of workplace violence. The lead researcher opted to not participate in the small groups, thus ensuring the agency or actions crafted were those of the board members and not the researcher. At the conclusion of small group sessions, the members came together for large group debriefings in which each member was provided the opportunity to discuss key agencies or actions to be incorporated into the prevention components. Later, each CAB member rated the priority and feasibility of prevention components. Equal value was given to the rating of each member. These processes facilitated equality in the voice and agency for each member.

4. Bidirectional Learning

One of the major benefits of community-engaged research is bidirectional learning, a process through which power can be shifted between academic and community partners leading to collective decision-making and, ultimately, outcomes benefiting the community.33 Mutual learning between researchers and community members results from understanding and valuing each other’s literacy frameworks. CABs provide a practical forum for this interchange of research and community literacies including the knowledge, language, and skills around research and the perspectives, needs, strengths, and capacity of the community, respectively.34 Further, interactions among CAB members can result in shared knowledge that catalyzes the adoption of culturally relevant and sensitive research methods and approaches. For example, Simonds and Christopher35 describe a CBPR project in an Indigenous community in which honest reflection and sharing among CAB members led to critical appraisal of Western data analysis techniques which were ultimately deemed to be inadequate and divergent from the local tribal outlook. Through persistent dialogue among CAB members, the research team worked together to identify approaches to analyze interview data in a manner that honored indigenous ways of knowing.

Path to Prevention

The Path to Prevention CABs represent regionally diverse American Indian tribal communities in the South-central and Northeast U.S. This research team is working together to develop and implement a cardiometabolic risk-reducing postpartum intervention for American Indian women with histories of gestational diabetes. In one community, CAB members shared information regarding existing local maternal/family health services and activities and developed strategies for creating synergy among these and the research program. They also encouraged the research team to partner with the tribal health system to streamline research activities with prenatal and postpartum visits. Conversations with the CAB promoted community members’ understanding and appreciation for key differences between ongoing demonstration projects and the team’s research project. This invaluable bi-directional learning has allowed researchers to better place their research in context and community members to build their capacity for evidenced-based practice.

5. Incorporating Bicultural Health Workers to Deliver the Intervention

Engaging members of the community into the design and delivery of interventions has been identified as a powerful component of effective interventions addressing health disparities.1 In fact, community health workers (CHWs), lay individuals from the community of interest that are trained to address health issues in their own community, have been identified as being integral to CBPR, demonstrating a positive impact on health outcomes.11 CHWs work to improve outcomes of interventions by overcoming cultural barriers to the targeted community, helping to provide access to the community, encouraging participant engagement, improving the quality of health promotion messages included in interventions, and improving health behaviors. Additionally, from the community’s perspective, CHWs and other people that help bridge the culture of the community and the culture of the research team help engender trust with the group being studied.12

The Partnership for Domestic Violence Prevention

The Partnership for Domestic Violence Prevention CAB was established in 2009 as one component of a larger community-academic partnership between the Miami Dade County Community Action and Human Services Department, Coordinated Victim Assistance Center and the University of Miami School of Nursing and Health Studies. The mission of the Partnership for Domestic Violence Prevention was originally to prevent intimate partner violence among Hispanics in Miami Dade County through research and evidence based practices, although the scope grew beyond this as time evolved. Bicultural health workers were incorporated in several ways. First, the development of the CAB was initially led by a Hispanic nurse researcher, a Hispanic academic community psychologist, and a Hispanic social service provider, all whom had experience bridging cultures and academic versus community perspectives. The CAB also included survivors of intimate partner violence and other stakeholders representing different communities of interest (e.g., Hispanics) and sectors (e.g., government, philanthropy, education). Finally, bicultural health workers implemented the research and intervention protocols that were informed by the Partnership for Domestic Violence Prevention CAB more broadly. For example, community members led focus group discussions with community members, delivered a teen dating violence prevention program for Hispanic families, and worked with academics to analyze and publish results.36, 37

Discussion

Given Nursing’s strong tradition of engaging individuals, families, and communities in making care decisions, nurses are uniquely positioned to lead community-engaged research. CABs can be a useful mechanism that nurse researchers can utilize to engage community members in the research process. There are several key components nurse researchers must ensure are present when working with CABs in community-engaged research efforts. These include incorporating real power-sharing structures between academic and community partners, ensuring true collaborative partnerships, engaging the voice and agency of the target community in the research protocol, nurturing bidirectional learning processes, and incorporating bicultural health workers for intervention delivery.11 These components help ensure partnerships within CABs result in constructive community-academic relationships and processes and positive health outcomes. These principles also have broad applications, regardless the health outcome and population of interest.

Although the principles for effective community-engagement were similar across CABs, they were uniquely implemented across research projects and communities. This was partly influenced by the existing infrastructure for community-engagement prior to the initiation of research projects and community preferences regarding how they wanted to be engaged. Some scholars were working with CABs that had been formed prior to the initiation of their research (i.e., Communities of Harlem Health Revival and the CAB for Center for Urban Youth and Families). Other scholars worked to create their own CABs because there were none in place prior to initiating their projects (i.e., Workplace Violence, Path to Prevention, and Partnership for Domestic Violence Prevention). In these cases, scholars worked within existing community structures to convene groups of individuals to respond to the expressed needs of the community, which had been identified in previous research and disseminated through publications coauthored with community partners.31, 32, 37–39 Although these CABs were formed after the research projects were initiated, they played an influential role in developing interventions to address priority problems in the communities. Communities engaged in the CABs had different preferences in the role they wanted to take in the organization of the boards. While some communities wanted to take the lead, others wanted to co-lead the board with researchers, and yet others preferred that the academic partners take the lead. These preferences were also reflected in the planning of co-authored publications and other dissemination strategies. As boards matured, the structure often changed according to community needs, preferences, and resources.

Challenges in Community-Engaged Research

Despite the promise of working with CABs for community-engaged research, RWJF NFS encountered several challenges in implementing the desired core elements of effective community-engaged practices. One of the greatest challenges was being able to balance service versus research demands from community and academic partners. This challenge was particularly salient when aiming to ensure real power sharing structures, collaborative relationships, and providing agency to beneficiary benefits. For example, communities were often interested in working with academic partners as a way to increase access to health services for the communities they were representing. NFS had to learn to be responsive to these identified service needs, although they often went beyond the scope of their research grants and were not always valued by university promotion and tenure review committees. RWJF NFS worked to balance these demands by volunteering their time outside their role as a faculty member, working with students to increase their reach, leveraging other university resources to improve their service and research productivity, and educating university administrators and faculty regarding the value of community-engaged research.

Traditional university structures posed another major challenge and often made true community-engagement difficult. In fact, in many cases university IRBs and financial offices did not have a strong existing infrastructure to engage community members as equal partners on research protocols and grant finances. For example, some RWJF NFS partnered with community organizations that did not have IRBs or the required federal registration to make them eligible to be overseen by university IRBs. Similarly, many community partners did not have the qualifications (e.g., education level) to qualify them for pre-established university positions that were aligned with the responsibility and appropriate compensation for their role on the research projects. The latter was particularly salient when engaging bicultural health workers in intervention delivery. RWJF NFS overcame many of these challenges by working closely and creatively with university administrators and serving as a translator between community and academic systems. Despite overcoming many of these challenges, there were some communities, which represent some of the most vulnerable groups in need of engagement (e.g., undocumented immigrants and children), where special arrangements could not be worked out. More research is needed to determine best practices in working with these groups through CABs and other community-engaged research strategies.

Conclusion

The proposed framework and RWJF NFS project exemplars present several implications for research. Nurse researchers who want to work with a CAB should begin by establishing a shared mission, vision, and strategic priorities across the stakeholders involved. Collaborative partnerships should be developed to help achieve the goal of promoting working relationships among community members, service providers from various disciplines and sectors, and other key stakeholders. Attention should be given to establishing and sustaining an equal voice for all members in these collaborations, paying attention to voices that traditionally have been marginalized in research. The strengths of the relationships developed through CABs should result in bidirectional learning opportunities and capacity building for all involved. When possible, bicultural health workers should be engaged to help bridge the multiple cultures, perspectives, and expertise. Nurse researchers often enter vulnerable communities with good intentions and ideas on how to address serious health inequities that adversely affect the health and wellbeing of community members. We recommend that nurse researchers embrace these evidence-based strategies for engaging communities to overcome challenges, maximize the potential for a positive impact on community health (e.g., reduce health disparities), and ensure that the processes used to achieve these outcomes are collaborative and responsive to the needs and strengths of the community.

Acknowledgments

The time needed to prepare this manuscript was supported primarily by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Nurse Faculty Scholars Program. Additional support for Dr. Gonzalez-Guarda was provided by the University of Miami School of Nursing Center of Excellence for Health Disparities Research: El Centro, National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities grant P60MD002266. For Dr. Cohn additional support was provided by Columbia University, Irving Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, through the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant Number UL1TR001873. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Contributor Information

Rosa M. Gonzalez-Guarda, Duke University School of Nursing.

Emily J. Jones, University of Massachusetts Boston, College of Nursing & Health Sciences.

Elizabeth Cohn, Adelphi University, Center for Health Innovation.

Gordon L. Gillespie, University of Cincinnati College of Nursing.

Felesia Bowen, Rutgers University School of Nursing.

References

- 1.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care (full printed version) National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes. John Wiley & Sons; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Research NIoN. Bringing life to science: NINR strategic plan. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Research NIoN. Program announcment: Community partnerships to advance research (CPAR) (R01) 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frank L, Basch E, Selby JV. The PCORI perspective on patient-centered outcomes research. Jama. 2014;312(15):1513–1514. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.11100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Satterfield JM, Spring B, Brownson RC, et al. Toward a transdisciplinary model of evidence-based practice. Milbank Quarterly. 2009;87(2):368–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00561.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson ET, McFarlane JM. Community as partner: Theory and practice in nursing. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Newman SD, Andrews JO, Magwood GS, Jenkins C, Cox MJ, Williamson DC. Community advisory boards in community-based participatory research: A synthesis of best processes. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8(3):A70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wallerstein N, Oetzel J, Duran B, Tafoya G, Belone L, Rae R. Community-based participatory research for health: from processes to outcomes. 2. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008. What predicts outcomes in CBPR. 371388. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Attree P, French B, Milton B, Povall S, Whitehead M, Popay J. The experience of community engagement for individuals: a rapid review of evidence. Health & social care in the community. 2011;19(3):250–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2010.00976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cyril S, Smith BJ, Possamai-Inesedy A, Renzaho AM. Exploring the role of community engagement in improving the health of disadvantaged populations: a systematic review. Global health action. 2015:8. doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.29842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belone L, Lucero JE, Duran B, et al. Community-based participatory research conceptual model community partner consultation and face validity. Qualitative health research. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1049732314557084. 1049732314557084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tran AN, Ornelas IJ, Kim M, et al. Results from a pilot promotora program to reduce depression and stress among immigrant Latinas. Health promotion practice. 2014;15(3):365–372. doi: 10.1177/1524839913511635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mendenhall TJ, Harper PG, Henn L, Rudser KD, Schoeller BP. Community-based participatory research to decrease smoking prevalence in a high-risk young adult population: An evaluation of the Students Against Nicotine and Tobacco Addiction (SANTA) project. Families, Systems, & Health. 2014;32(1):78. doi: 10.1037/fsh0000003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baig AA, Locklin CA, Wilkes AE, et al. Integrating diabetes self-management interventions for Mexican-Americans into the catholic church setting. Journal of religion and health. 2014;53(1):105–118. doi: 10.1007/s10943-012-9601-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanson LC, Armstrong TD, Green MA, et al. Circles of care development and initial evaluation of a peer support model for African Americans with advanced cancer. Health Education & Behavior. 2012 doi: 10.1177/1090198112461252. 1090198112461252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corbie-Smith G, Adimora AA, Youmans S, et al. Project GRACE: A staged approach to development of a community—Academic partnership to address HIV in rural African American communities. Health Promotion Practice. 2011;12(2):293–302. doi: 10.1177/1524839909348766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DiClemente RJ, Salazar LF, Crosby RA. Health behavior theory for public health: principles, foundations, and applications. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKinney M. Engaging research. First PCORI grants focus on involving patients and families. Modern healthcare. 2012 Jun 25;42(26):14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barr P. Collaborative efforts: PCORI comparative-effectiveness awards add a new twist: patient input. Modern healthcare. 2012 May 28;42(22):12–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Methodology Committee of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research I. Methodological standards and patient-centeredness in comparative effectiveness research: the PCORI perspective. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2012 Apr 18;307(15):1636–1640. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Selby JV, Beal AC, Frank L. The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) national priorities for research and initial research agenda. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2012 Apr 18;307(15):1583–1584. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.(PICORI) PCORI. Engagement Rubric for Researchers.

- 24.Ross LF, Loup A, Nelson RM, et al. The challenges of collaboration for academic and community partners in a research partnership: Points to consider. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 2010;5(1):19–31. doi: 10.1525/jer.2010.5.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. 4. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mattessich PW, Monsey BR. Collaboration: what makes it work. A review of research literature on factors influencing successful collaboration. ERIC; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roussos ST, Fawcett SB. A review of collaborative partnerships as a strategy for improving community health. Annual review of public health. 2000;21(1):369–402. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kotzé M, Seedat M, Suffla S, Kramer S. Community conversations as community engagement: hosts’ reflections. South African Journal of Psychology. 2013;43(4):494–505. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simmons C, Graham A, Thomas N. Imagining an ideal school for wellbeing: Locating student voice. Journal of Educational Change. 2015;16(2):129–144. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graham A, Fitzgerald R. Progressing children’s participation: Exploring the potential of a dialogical turn. Childhood. 2010;17(3):343–359. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gillespie GL, Gates DM, Kowalenko T, Bresler S, Succop P. Implementation of a comprehensive intervention to reduce physical assaults and threats in the emergency department. Journal of Emergency Nursing. 2014;40(6):586–591. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gillespie GL, Pekar B, Byczkowski TL, Fisher BS. Worker, workplace, and community/environmental risk factors for workplace violence in emergency departments. Archives of environmental & occupational health. 2016 doi: 10.1080/19338244.2016.1160861. just-accepted 00-00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. American journal of public health. 2010;100(S1):S40–S46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Granberry PJ, Torres MI, Allison JJ, et al. Developing Research and Community Literacies to Recruit Latino Researchers and Practitioners to Address Health Disparities. Journal of racial and ethnic health disparities. 2016;3(1):138–144. doi: 10.1007/s40615-015-0123-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simonds VW, Christopher S. Adapting Western research methods to indigenous ways of knowing. American journal of public health. 2013;103(12):2185–2192. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gonzalez-Guarda RM, Guerra JE, Cummings AA, Pino K, Becerra MM. Examining the preliminary efficacy of a dating violence prevention program for Hispanic adolescents. The Journal of School Nursing. 2015 doi: 10.1177/1059840515598843. 1059840515598843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gonzalez-Guarda R, Cummings A, Becerra M, Fernandez M, Mesa I. Needs and preferences for the prevention of intimate partner violence among Hispanics: A community’s perspective. The journal of primary prevention. 2013;34(4):221–235. doi: 10.1007/s10935-013-0312-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones EJ, Peercy M, Woods JC, et al. Peer Reviewed: Identifying Postpartum Intervention Approaches to Reduce Cardiometabolic Risk Among American Indian Women With Prior Gestational Diabetes, Oklahoma, 2012–2013. Preventing chronic disease. 2015:12. doi: 10.5888/pcd12.140566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gonzalez-Guarda RM, Diaz EGL, Cummings AM. A community forum to assess the needs and preferences for domestic violence prevention targeting Hispanics. Hispanic health care international. 2012;10(1):18–27. doi: 10.1891/1540-4153.10.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]