Abstract

Background:

Accountable care organizations (ACOs) are becoming a common payment and delivery model. Despite widespread interest, little empirical research has examined what efforts or strategies ACOs are using to change care and reduce costs. Knowledge of ACOs' clinical efforts can provide important context for understanding ACO performance, particularly to distinguish arenas where ACOs have and have not attempted care transformation.

Purpose:

The aim of the study was to understand ACOs' efforts to change clinical care during the first 18 months of ACO contracts.

Methods:

We conducted semistructured interviews between July and December 2013. Our sample includes ACOs that began performance contracts in 2012, including Medicare Shared Savings Program and Pioneer participants, stratified across key factors. In total, we conducted interviews with executives from 30 ACOs. Iterative qualitative analysis identified common patterns and themes.

Results:

ACOs in the first year of performance contracts are commonly focusing on four areas: first, transforming primary care through increased access and team-based care; second, reducing avoidable emergency department use; third, strengthening practice-based care management; and fourth, developing new boundary spanner roles and activities. ACOs were doing little around transforming specialty care, acute and postacute care, or standardizing care across practices during the first 18 months of ACO performance contracts.

Practice Implications:

Results suggest that cost reductions associated with ACOs in the first years of contracts may be related to primary care. Although in the long term many hope ACOs will achieve coordination across a wide array of care settings and providers, in the short term providers under ACO contracts are focused largely on primary care-related strategies. Our work provides a template of the common areas of clinical activity in the first years of ACO contracts, which may be informative to providers considering becoming an ACO. Further research will be needed to understand how these strategies are associated with performance.

Key words: delivery reform, health care organizations, health policy, payment reform, primary care

Accountable care organizations (ACOs) are quickly becoming a common care delivery and contracting model. The ACO model provides financial incentives to provider groups for controlling the total costs of care as well as for delivering high-quality care to their patient population. In many ways, the model is simple—ACO policies and contracts contain few prescriptions for how health care providers should attempt to achieve low-cost care. Commenters and researchers have discussed many possibilities of ACO coordination, activities, and effects across a wide variety of settings and providers, including surgery (Dupree et al., 2014), specialists (Goodney, Fisher, & Cambria, 2012; Joynt, 2014), behavioral health (Bao, Casalino, & Pincus, 2013; Maust, Oslin, & Marcus, 2013), primary care (McWilliams, 2014), pharmacy (Morden, Schwartz, Fisher, & Woloshin, 2013; Smith, Bates, & Bodenheimer, 2013), postacute care, (McWilliams, Chernew, Zaslavsky, & Landon, 2013), cancer care (Bernstein, 2013), and pediatrics (Homer & Patel, 2013).

As ACOs have moved from idea to reality, research has begun to assess characteristics of ACOs (Colla, Lewis, Bergquist, & Shortell, 2016; Colla, Lewis, Tierney, & Muhlestein, 2016; Dupree et al., 2014; Epstein et al., 2014; Lewis, Colla, Schoenherr, Shortell, & Fisher, 2014; Lewis, Colla, Schpero, Shortell, & Fisher, 2014; Lewis, Colla, Tierney, et al., 2014; Shortell, Wu, Lewis, Colla, & Fisher, 2014) and early effects of ACOs (Chien et al., 2014; Colla, Lewis, Kao, et al., 2016; McWilliams, Chernew, Landon, & Schwartz, 2015; McWilliams, Hatfield, Chernew, Landon, & Schwartz, 2016; Song et al., 2014). However, no research has directly examined the clinical strategies and priorities of ACOs. How are ACOs attempting to reduce costs and improve care? Understanding ACOs’ activities can inform both policymakers and researchers. Specifically, it is critical that we understand what ACO providers are attempting to do before identifying outcome measures to evaluate these efforts. For example, if ACOs are targeting specific populations, such as diabetics, we would hope to see changes in outcomes for this cohort; similarly, if ACOs are not actively working to reduce spending on other specific subgroups, such as cancer patients, it should be no surprise if care for this group does not change. Across these priorities for improving care, many expect ACOs to improve care coordination and management of patients across diseases, settings, and providers.

To date, analysis of ACO effects has been relatively uninformed about the activities of ACOs on the ground. When evaluation finds small or no effects on specific clinical or spending outcomes (Chien et al., 2014; Colla et al., 2014), it is unclear whether this is because ACOs have tried and failed to affect change in this area, or if in fact ACOs have not yet tried at all with regard to the particular condition or cohort studied. In this article, we focus on understanding both what and how ACOs are attempting to change and coordinate clinical care.

Dimensions of Improved Clinical Care and Coordination

Perhaps the most central topic in the discourse on ACOs is improved coordination, which many anticipate will transform clinical outcomes and care for patients. Proponents of ACOs hope that ACOs will improve the way health care providers coordinate and deliver care, from coordination within a single visit (e.g., improved previsit planning or team-based care) to coordination across settings and providers for complex patients (e.g., coordination between primary care, postacute care, and hospitals; Colla, Lewis, Bergquist, et al., 2016; Deremo et al., 2014; Joynt, 2014; McWilliams, Landon, Chernew, & Zaslavsky, 2014). Improved coordination is hoped to reduce duplication, increase quality of care, and reduce unnecessary costs associated with fragmented care, as well as improve patients’ experiences with health care.

Although coordination within ACOs is often discussed, there is little agreement or understanding of how ACOs may best coordinate care or even how to define or conceptualize care coordination. One review found over 40 distinct definitions of care coordination in the existing literature on care delivery (McDonald et al., 2007). The term “care coordination” is often used loosely to refer to any care provided outside of the direct physician–patient clinical interaction, generally intended to extend or reinforce office-based treatment, such as providers of different specialties discussing a shared patient. In order to best understand clinical coordination efforts of ACOs, we first aimed to clarify the central concepts of improved clinical coordination. On the basis of the work of Gittell and colleagues (Gittell, 2002; Gittell, Seidner, & Wimbush, 2010; Gittell & Weiss, 2004), we identified several key domains for coordination in clinical care: routines, boundary spanning, and team meetings. Routines refer to the extent to which care delivery services are coordinated and routinized through care management protocols, clinical pathways, and best practice guidelines. Routines remove some of the burden on clinicians by providing a structure for beneficial activities and practices. We identified several major components of routines potentially important for clinical care: disease or care management programs, standardized treatment guidelines, and care transition protocols.

Team meetings (and team-based care more generally) facilitate interactions among participants engaged in the same processes. By providing a forum for direct communication, these meetings allow for timelier and more interactive coordination of tasks, which increases performance of interdependent work.

Boundary spanning refers to activities that integrate the work of multiple people or departments. In the case of clinical care, we consider boundary spanning as work that occurs across existing organizational boundaries (e.g., between two separate physician practices), across provider specialties (e.g., between a cardiologist and a primary care physician), or across settings (e.g., between an emergency department [ED] and a primary care practice). The role of boundary spanners is to work across multiple aspects of a patient’s care rather than focusing on direct care delivery in one setting.

Drawing on this framework, we distinguish between care management and boundary spanning. We define care management as the set of routines (including programs and systems) aimed to help manage patients’ health and medical conditions. This definition of care management combines elements of case management and disease management into an overall rubric of “care management.” Care management might include programs involving self-management, home visits, patient education, medication reconciliation, discharge planning, disease registries, chronic disease management, care planning, telephonic nurse call lines, and wellness initiatives. Notably, under our definition care management largely involves providers working directly with patients.

In contrast, we define care coordination as synonymous with boundary spanning, referring to activities integrating care across organizations, providers, and settings (Gittell & Weiss, 2004), such as improving communications between ED care and primary care or facilitating transitions between postacute care facilities and hospitals. Boundary spanning often involves communication or work between providers and often immediately involves multiple providers (e.g., a specialist and a primary care provider discussing a patient’s care), with the ultimate goal of improving patient care.

In addition to the elements of clinical coordination, there are two additional, overlapping forms of coordination that are outside the domain of this article but worth noting here: structural coordination (or integration) and relational coordination. Structural or organizational coordination refers to areas such as coordination of human resources and leadership and management structures. Relational coordination refers to the existence of trust, mutual respect, and communication. Work has shown that relational coordination mediates the effectiveness of clinical coordination activities (Gittell, 2002).

The Research Gap

The role of ACOs in improving or increasing coordination is currently unknown, although some work has begun to examine this question in various specific domains (Colla, Lewis, Bergquist, et al., 2016; Lewis, Colla, Tierney, et al., 2014; Rundall, Wu, Lewis, Schoenherr, & Shortell, 2016). Proponents of ACOs envision that ACOs will improve the ability of providers to coordinate care. As Gittell notes, “organizations…enable coordination to occur more readily than can be achieved in their absence” (Gittell, 2002). New ACO policies and supports may bolster the ability of ACOs to improve coordination of care. However, to date research on ACO activities is often limited to a single domain (e.g., studying coordination in a single setting, such as behavioral health (Lewis, Colla, Tierney, et al., 2014) or surgery (Dupree et al., 2014). No examination of ACO’s clinical activities currently exists that has comprehensively considered the various domains and activities ACOs are engaged in to foster more in-depth evaluation of ACO programs. Qualitative research will be critical to an in-depth understanding of ACO efforts and will inform evaluation of ACO outcomes.

In this article, we provide an empirical examination of common activities ACOs are undertaking in care delivery during the early stages of ACO performance contracts. Specifically, we use data from interviews with 30 ACOs to understand what clinical programs, activities, and settings ACOs are targeting to coordinate care in the first year of ACO contracts. Results suggest that, during this initial period, ACOs are focusing on transforming primary care, reducing avoidable ED use, strengthening care management, and expanding boundary spanning roles and activity through a combination of routines, team-based care, and boundary spanning.

Methods

We conducted semistructured interviews with executives at 30 ACOs between July and December of 2013. ACOs were selected from respondents to the first wave of the National Survey of ACOs (n = 173). The National Survey of ACOs included all organizations that were potentially ACOs and screened for eligibility at the beginning of the survey; organizations were defined as ACOs if they had a contract that held providers financially responsible for both quality of care and cost of care delivered to their patient population.

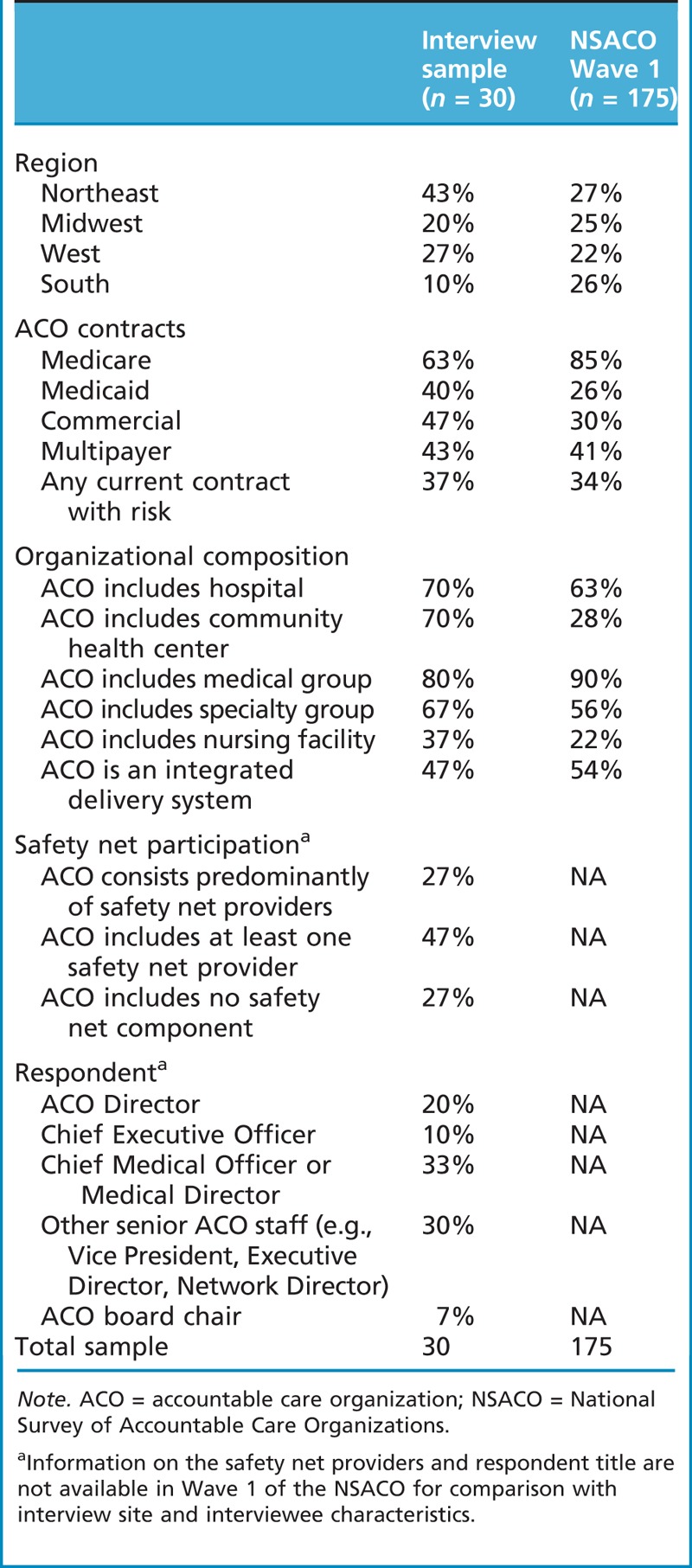

We stratified our interview sample to include ACOs across domains of structure, geographic region, and patient population (e.g., whether or not the ACO included safety net providers). We conducted e-mail and phone outreach with 39 ACOs and achieved 30 total interviews. At the time of interviews, organizations were in the first 12–18 months of their ACO contract(s) with any payer; a few organizations had ACO contracts with multiple papers. During outreach, we gave sites information on the broad topics for the interview, and we asked them to identify the person in their ACO most knowledgeable to speak to those topics. Table 1 presents characteristics of interviewed sites and the full set of ACOs in Wave 1 of the National Survey of ACOs, including the position or title of the specific interviewees we spoke with.

Table 1.

Characteristics of ACOs interviewed compared to full sample in NSACO

A substantial portion of each interview focused on ACOs’ care delivery. The interview guide was developed to elicit detailed information on the clinical activities that resulted from ACO formation (see appendix for interview questions). Interviewers probed respondents on a variety of topics related to care delivery, starting with open-ended questions about changes in care delivery resulting from the ACO. We probed on specific topics on domains of coordination identified above: disease and care management programs, including disease registries; team-based care or clinical meetings that span specialties, settings, or organizations; care transition programs and protocols; introduction of boundary spanning roles; shared patient data; and standardized treatment guidelines. In addition, we probed on efforts to identify high-risk patients and care settings on which ACO strategies were focused. Our interviews also elicited information about other ACO characteristics, including ACO formation, governance and committees, shared savings distribution, communication, and safety net provider participation. This article touches on these topics only as they relate to care delivery.

Interviews were recorded and transcribed. A code list was developed based on a priori topics of interest (such as aspects of care delivery and settings of care), and additional codes were added once interviews were complete to additional topics emerging from the data.

A team of four coders coded interviews using NVivo software; coders went through a process of iterative coding and review until the group reached a Kappa of 0.60, a threshold of acceptable intercoder reliability. We also had a process to review and discuss coding. First, the coders (led by authors KS and VL) reviewed each others’ coding to qualitatively judge coding overlap. Second, while coding each coder noted places in transcripts where there was a question; the coders came together to discuss discrepancies and questions. This process was repeated after coding one to two transcripts until authors felt confident in shared code definitions and coding overlap. In addition, during analysis, authors performed spot checks on coding, reviewing portions of transcripts relevant to themes to verify coding.

Once coding was complete, we grouped codes into general themes. We began by pulling queries on each of the codes and creating summaries of coded material for each code. This process allowed us to quickly determine topics that were infrequently discussed and dropped from subsequent analysis. From here, we began to group topics and codes into broader themes. We used an iterative process of analysis and memo writing to generate themes, discuss themes among authors, and return to the data to verify or refine themes. These themes were abstracted into the results presented in the following section. We give examples to illustrate findings, using anonymized ACO numbers to present the spread of data.

A challenge in interviewing and analyzing our data was around the terms care management and care coordination, often used interchangeably by providers. We opted to address this issue in two ways. In interviews, we mirrored respondents’ language when discussing ACO activities. For example, if a respondent discussed a “care management program,” we also referred to the program as a care management program during the interview, regardless of the content of the program. In contrast, for the purposes of coding and analyzing our data, we developed definitions to distinguish activities. In this article, we define care management as the set of programs and systems aimed to help manage patients’ health and medical conditions, a combination of activities often referred to as disease management or case management. We use boundary spanning to indicate activities coordinating or organizing care across multiple settings, practices, or providers. For example, boundary spanners may work to share information between ED physicians and primary care practices. This work can fall under a number of different roles within provider organizations and practices. We avoid using the term “care coordination” for clarity.

Results

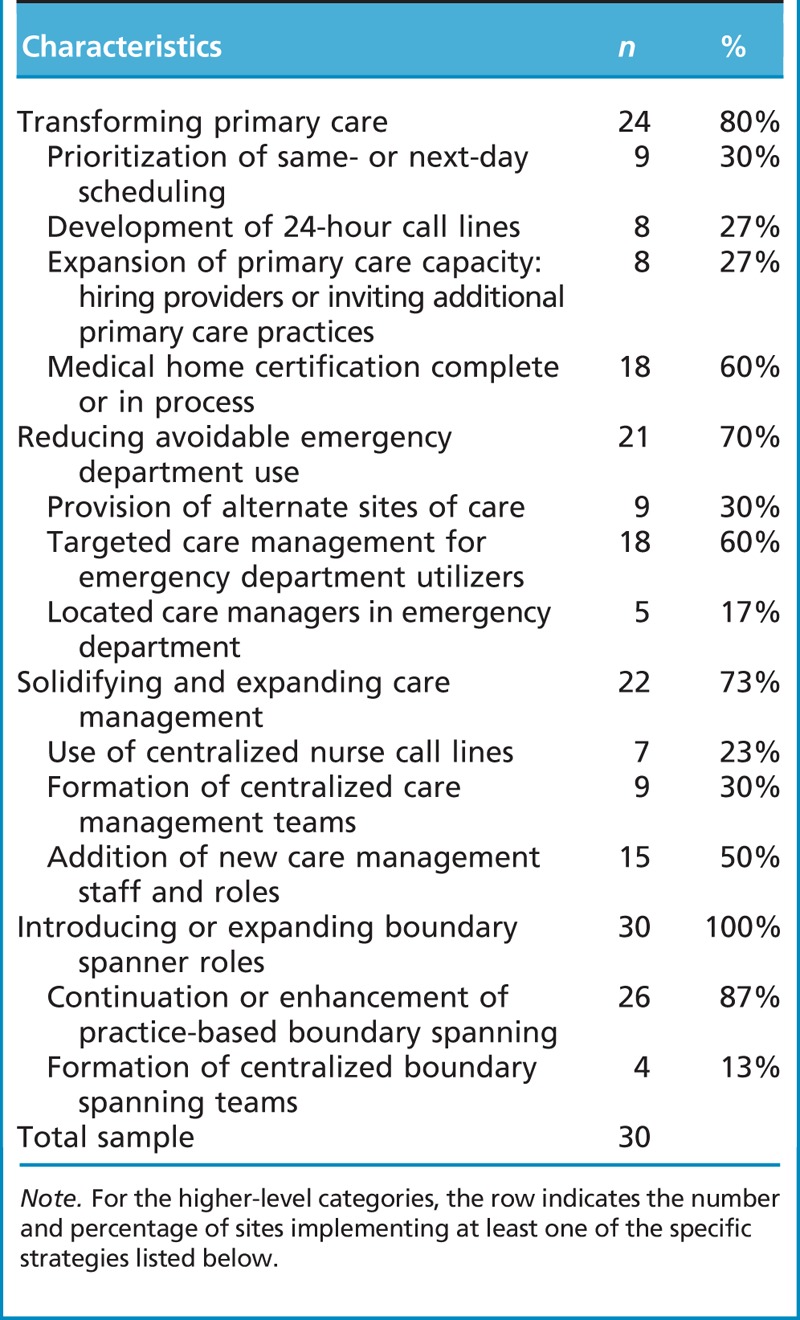

Our analysis revealed four major areas of focus on care delivery during the early stages of ACO development: transforming primary care, reducing avoidable ED use, solidifying care management, and introducing new boundary spanner roles. We describe each of these efforts in more detail, including how these activities relate to one another. Table 2 presents descriptive statistics from our sample on the strategies discussed throughout this section, including the total number of sites implementing the particular strategy and the percentage of the overall sample that number represents.

Table 2.

Care transformation strategies pursued by accountable care organizations in sample

Primary Care Transformation

Respondents reported that ACO initiatives allowed for an increased role and greater flexibility in the way primary care was being provided. Discussing the period before ACO implementation, one respondent stated a sentiment reflected by several interviewees, “[Before the ACO] the hospital did not do enough to recognize the role that the primary care physician plays in controlling the cost around various episodes of care…. A lot of the focus was on the specialty physicians and not enough on where the patients were being referred from” (ACO 2). Respondents reported a change in focus as they pursued accountable care. One respondent stated succinctly, “Primary care is the starting point of how we’re pursuing the accountable care organization” (ACO 26). Overall, ACOs focused on two major ways to transform primary care, increasing access to primary care and building robust primary care teams, as well as data as a motivation for change.

Primary care access

ACOs pursued better primary care access through improved same-day or next-day scheduling, development of 24-hour call lines for patients, and extended hours for primary care practices. For example, one ACO (ACO 6) relied on several of these strategies. The ACO’s primary care practices added hours on the weekends, increased availability of same-day appointments, and started a phone triage service. The phone service was in-house, staffed by nurses with access to patients’ electronic health records and who could schedule next-day appointments when necessary. A major goal of increased access across ACOs was reducing avoidable ED use (discussed in the next section).

Primary care teams

In addition, ACOs focused on building robust primary care teams where the primary care provider served as a “quarterback.” As described by one ACO, “A strong goal is to make sure that the primary care docs are kind of a captain of the team…they’re the ones who are involved and get all the information about what’s happening with the patient” (ACO 23). Other team members were often care managers, nurses, and mid-level practitioners.

In building primary care teams, 60% of ACOs interviewed discussed pursuing medical home certification as part of their care transformation approach (including those at any stage of certification, from complete to in-progress). ACOs hoped to leverage the primary care focus of medical homes to improve overall primary care functioning. For ACO providers without experience in population health or ACO-like contracts, medical home certification seemed a practical action ACOs could take while developing other clinical strategies. Some ACOs deliberately chose to have primary care practices pursue certification as a result of the ACO, whereas other ACOs used certification as a prerequisite for joining the ACO. All who reported pursuing medical home certification saw medical homes as tightly aligned with ACO goals.

Importance of new data to prioritizing primary care

A final important theme around primary care transformation was the importance of new data for primary care providers. ACO primary care providers often gained access to new data that provided them with much more information on patterns of care, utilization, and costs associated with their patients, either through internal ACO data sharing or administrative and claims data provided by the ACO payers. Understanding care provided outside the primary care practice often served as a motivator for primary care transformation. For example, when one ACO (ACO 10) received claims data from their payer, clinical leadership was surprised to discover that ED use among their patients was as high during times when primary care practices were open as when practices were closed. This prompted the ACO to engage in a process of revamping their primary care same-day scheduling to allow more patients to get urgent appointments.

Reducing Avoidable ED Use

All ACOs we interviewed discussed working to reduce avoidable ED use, with several identifying it as one of their ACO’s top priorities. The common focus on ED use was due in large part to new data ACOs received from payers under ACO contracts. For many ACO providers, these data provided the first clear picture of ED use across their primary care patient population. Primary care providers participating in ACOs reported surprises in these data. As one respondent stated, “I think we have now got a better understanding, Oh my god, what’s going on here? We had a patient going to the emergency room 17 times. If we didn’t have the ACO, if we were not having the data to show it, guess what? We all would think we are doing great” (ACO 9). Once ACOs identified ED use as a priority, they focused on what concrete strategies or efforts they might employ to reduce avoidable ED visits, including increasing primary care access (discussed previously), diverting nonsevere cases from the ED, and targeting care management resources to high ED utilizers.

Several ACOs were working to divert patients to alternate sites of care that were lower cost than the ED when neither the ED nor primary care practice was ideal. Urgent care clinics were commonly mentioned, although there were other strategies as well. For example, one ACO (ACO 12) developed a pilot with local ambulance companies where ambulances would transport patients with a specific set of diagnoses to an urgent care clinic rather than an ED. The ACO paid the ambulance companies for this service, which otherwise would not be reimbursed. The ACO viewed this as a way to use existing emergency responders to curb avoidable ED use and provide patients with appropriate care. Two ACOs (ACOs 12 and 13) discussed creating new or expanding existing sobering centers or detoxification facilities; the goal of these centers was to provide lower cost locations than the ED for patients to detoxify.

Nearly all ACOs were working to target care management for high ED utilizers. As one ACO stated, “[We’re] focusing the care management and the care coordination team like a laser on those [high ED users] to make sure that they’re getting in to see their docs when they need to, they’re taking their meds, that if they’re having a problem, they know they can call up the care [manager] at 3:00 a.m. on Sunday, if you need to…all this stuff to make sure that they don’t go to the ER unnecessarily” (ACO 23). Although almost all ACOs had care management services prior to the ACO (discussed in the next section), the focus on avoidable ED use gave care management new or enhanced emphasis. For example, five ACOs interviewed implemented a new care management approach of locating care managers in EDs. These care managers provided patient education upon discharge intended to improve patient adherence to treatments or medications, facilitated follow-up with primary care practices, and/or helped connect patients to other providers or social services. ACOs reported that these were new efforts directly stemming from their participation in an ACO contract.

Solidifying and Expanding Care Management

ACOs were providing a wide range of care management and patient outreach services prior to ACO development. Notably, every organization interviewed had some existing staff dedicated to care management work prior to their ACO contract. With many care management programs and staff already in place, ACOs had to decide whether to keep care management decentralized and based on primary care practices or move toward ACO-wide, centralized care management. Practice-based care management allowed each practice to tailor services to patient needs, whereas centralized care management provided more uniform services to all ACO patients. Most ACOs interviewed (70%) chose to keep care management decentralized. One ACO described how it had come to one such decision. “Within [our chronic disease self-management program] we started first by offering classes at centralized locations, and we quickly discovered that that was not a good model…. So we have decided to decentralize” (ACO 2). An emphasis on decentralized, practice-based care management reinforced the idea that primary care was the central hub of patient care, as primary care teams were the basis for care management. Although the ACOs interviewed had almost all decided to keep care management decentralized, there was a significant push to bolster existing care management by adding new staff or changing the focus or operations of care management. Several ACOs (50%) hired additional care management staff, such that each primary care practice had one or more full-time care managers working with patients.

One disadvantage of the practice-based approach to care management was that effectiveness often varied considerably across practices within an ACO. To reduce variation, ACOs were working to share best practices across providers. Many ACOs had committees on clinical care or quality improvement and relied on this venue for sharing care management practices. In some ACOs, staff members were tasked with sharing best practices. As one primary care practice described, “[The ACO] medical director who was over yesterday…was writing down our care management model. Who’s part of the team? Do you do home visits? What kind of education programs do you have for them?” (ACO 2) The medical director planned to share this information with ACO practices with less developed care management models. Other ACOs were taking a more direct approach, such as providing standardized training across practices. For example, one ACO (ACO 9) was planning to train practices’ care management staff on a variety of topics, beginning with personal health assessments and the identification of high-risk patients.

A few ACOs were pursuing centralized care management strategies, including centralized care management call lines (23% of ACOs interviewed) and centralized care management teams (30%). Shared call lines were helpful to some ACOs, such as two ACOs (ACO 9, ACO 19) that encompassed providers spread across large geographies. Centralized care management teams worked with patients identified as the highest utilizers or most difficult. For example, at one ACO a centralized team worked with patients who visited the ED 50–80 times per year (ACO 13). ACOs with centralized call lines or care management teams faced a significant challenge in linking these resources back to the primary care practice, a challenge also faced by care coordination efforts discussed next.

Introducing New Boundary Spanning Roles

We found two models for implementing boundary spanning activities within ACOs. The first model involved boundary spanners who were based on a single practice at an ACO, such as a primary care practice; the second involved a centralized boundary spanner role or team working across ACO providers.

In most ACOs, boundary spanners were embedded in individual primary care practices (87% of our interviewees). Typically, ACOs that followed this model did not have an overall, formal system of coordination but instead relied on the impact of individual boundary spanners. Often, these individuals were care managers providing limited boundary spanning activity. For example, one ACO consisted of four primary care clinics (ACO 25); as part of the ACO initiative, each clinic hired a new staff member who provided largely care management, such as patient education, but also did some limited coordination work with local hospitals.

A second, less common model of boundary spanning (13% of ACOs interviewed) was the formation of new ACO level coordination teams. These centralized teams were layered on top of practices’ existing care management infrastructure and worked to connect across ACO providers, such as across hospitals and primary care practices. At one ACO (ACO 2), this team consisted of three nurse case managers, a social worker, and a medical director and received support from pharmacy and psychiatry. The team worked to interface between the ACO’s major hospital and the primary care practices, often serving as a liaison between practice-based care managers and the hospital’s discharge planners. This particular model of the centralized team allowed for boundary spanning without overhauling existing care management roles at the practice level. However, this model was not without challenges; ACOs implementing centralized coordination teams were grappling with the best way to effectively link centralized teams into practice-based care management.

Care and Activities Not Targeted by ACOs

Our interviews included questions or probes about several areas of care delivery that few ACOs were addressing. ACOs interviewed were largely not focusing efforts on inpatient hospital care or specialty care at the time of interviews, except a few cases where ACOs were working to build better relationships between primary care providers and specialists. Likewise, few ACOs were focused on any strategies around nursing homes or postacute care, such as improving care transitions between hospitals and postacute care facilities. Only a small number of interviewed ACOs were focused on linking patients to social services that might help improve health, health care, or cost outcomes. In addition, although all ACOs were working to improve care, few were using formal quality improvement strategies; ACOs employing formal quality improvement were typically more advanced existing health care systems with prior quality improvement experience, whereas ACOs that consisted of smaller practices or clinics with less experience with quality improvement or risk based contracts typically were not using formal quality improvement strategies.

Variation Across ACOs

Our sampling strategy was designed to illuminate how ACOs were changing care across varied types of ACOs. Through our interviews and analysis, we determined that regardless of patient population (e.g., disadvantaged or not, elderly vs. non-elderly patients), contracts (i.e., Medicare, commercial, Medicaid), or structure (e.g., hospital included or not), ACOs were using the same basic approaches and strategies described above.

Approaches were sometimes tailored to the ACOs’ specific patient populations or providers, while built on the same central emphases described above. For example, one ACO that consisted of a public hospital, a federally qualified health center, and an affiliated provider network served a patient population with higher rates of mental illness and chemical dependency than other ACOs interviewed. Similar to other ACOs, they focused on reducing avoidable ED use but tailored this strategy to their specific patient population by creating a new detoxification facility where patients could safely detoxify outside of the ED. Similarly, one ACO with a Medicare contract was working on ED diversion by developing protocols for local nursing homes and postacute care facilities around when to send patients to the ED. In both of these cases, the ACO was focused on diverting avoidable ED use, although each specific strategy was tailored to the needs of the patient population.

As another example, strategies to increase primary care access were notably different for specific patient populations. As described above, some common strategies of ACOs were to embed providers in key locations to provide better patient access to appropriate care and reduce unnecessary ED use. An abscess clinic in a public housing unit was one form of embedding providers in external locations, while placing nurse practitioners in local nursing homes was another version.

Synthesis of Themes

The four themes presented are not mutually exclusive; rather, the four are highly intertwined. For example, reducing avoidable ED visits was being achieved largely through improved primary care access, care management for patients using the ED, and improved boundary spanning for patients leaving the ED to prevent unnecessary returns. In addition, because care management was largely decentralized and practice based, strengthened care management often went hand-in-hand with primary care transformation. In the case of ACOs pursuing medical homes, care management was being built into the basic functioning of primary care teams. Boundary spanning activities were also in many cases a subset of the work being done in care management, and only a handful of advanced organizations were creating more robust boundary spanning routines, personnel, or teams. The overlapping nature of our themes is also evident in the co-occurrence: All of the sites interviewed were pursuing at least two of the major themes, with 13 pursuing all four strategies and 11 pursuing three strategies.

Overlaying these areas with the domains of coordination identified at the beginning of this article, ACOs were working to improve care through routines, team-based care, and, to a lesser extent, boundary spanning. Primary care transformation was done largely through changing routines (e.g., improving routines for after office care or same day appointments) as well as team-based care, largely following the medical home model. Efforts to reduce ED use were targeted largely through routines, including care management routines as well as routines around ED usage (through establishing protocols for appropriate ED use and alternate sites of care). Strengthened care management involved a number of routines, such as implementing self-management classes for patients or standardized protocols for chronic disease care. Finally, ACOs were beginning to engage in boundary spanning activity, although this activity was often somewhat limited.

Discussion

Overall, we found four common emphases across ACOs interviewed: transforming primary care, reducing avoidable ED use, solidifying and expanding care management, and introducing new boundary spanner roles. These were common across ACOs with varied patient populations and organizational compositions, although the exact nature of implementation was often tailored to specific patient populations. For example, the emphasis on primary care was common across both ACOs that included a hospital and ACOs that included only outpatient physician practices. In contrast, although the major emphases were similar across ACOs, implementation often varied based on an ACO’s specific patient population. Thus, it appears that the ACO model has encouraged similar areas of focus among providers while simultaneously allowing flexibility for providers to tailor the model to their particular patient population.

Although we did uncover some aspects of care delivery that ACOs were not focused on at the time of our interviews, this does not mean ACOs will never focus their efforts on these settings. We anticipate that there is a common ACO development process across provider organizations that initially focuses on primary care enhancement and then moves toward other care settings and providers. Establishing a solid foundation in primary care may necessarily precede activities focused on other settings and providers. ACOs may diverge in strategy as they progress, such that the common elements of ACO development in early years may give way to multiple, varied strategies for reducing costs and improving care (Shortell et al., 2014).

We expect that ACOs may be successful at achieving cost and quality performance through implementation of routines of many sorts, such as standardized care pathways or care transition protocols. ACOs may be able to leverage both the data available through their ACO enterprise as well as the financial incentives in ACO contracts to implement routines among providers. In addition, we expect that ACOs could create value through boundary spanning, as ACOs may be able to create improved mechanisms to integrate work across primary care, specialty care, and acute and inpatient settings.

An important consideration is the reliance of a high number of ACOs in this study on medical home certification. Improving primary care access and improving care management are two key strategies ACOs are pursuing that are well aligned with goals of medical homes. If, as we suggest, ACOs follow a development trajectory that begins with clinical efforts based largely on primary care, it may be that medical home certification outlines the initial or foundational steps for ACOs to ensure that they provide patient-centered care before they begin larger care transformation. A more functionalist view may be that medical home certification provides ACOs concrete direction through a list of requirements, in contrast to ACO contracts, which provide financial rewards but leave providers almost complete autonomy and discretion in determining priorities and activities.

As ACOs continue to develop, we expect that they will differ from medical homes in a few key ways. First, once ACOs have accomplished work in patient-centered primary care, we theorize that providers will move to efforts in areas that are largely beyond the reach of medical homes, such as improving specialty care, postacute care, or hospital-based care. Furthermore, medical homes are focused on primary care practices, whereas ACOs have broader sets of providers and are financially responsible for care that happens in other settings. Future work could examine the optimal evolution; for example, research could analyze if providers are more successful if they meet medical home requirements before executing an ACO contract.

This work has important limitations. First, our findings are based on a set of 30 ACOs. Analysis with a much larger sample would be required to understand how common each of these emphases or strategies are or how the strategies vary by types of ACO (e.g., ACOs with hospitals and those without). In addition, our work cannot address how these strategies are related to performance on either quality or cost outcomes. Linking ACO strategies to performance data would provide much-needed insights as to what facilitates success in this payment and delivery model. For example, recent research on Medicare ACO performance has shown considerable variation in performance across Medicare ACOs (Colla, Lewis, Kao, et al., 2016; McWilliams et al., 2014, 2015) and has identified broadly some provider characteristics associated with performance (McWilliams et al., 2016). However, this work on performance to date has not examined specific strategies or areas of ACO focus that are associated with performance. This article, in contrast, illuminates the activities of ACOs, suggesting domains of outcomes where researchers may expect to see changes in the first 1–2 years of an ACO contract as well as context for understanding why other domains of outcomes may not see early results in ACO programs (Colla et al., 2014).

Overall, this work suggests that organizations participating in ACO contracts began significant attempts to meaningfully reorganize or redesign care in the first year of ACO contracts. The emphasis on transforming primary care is a welcome one to proponents of reform who look to payment reforms to realign our country’s health care priorities. In addition, the tailoring of the model across populations suggests an important flexibility. Of course, it is unknown to what extent ACO reforms and ACOs themselves will be able to fundamentally alter cost growth and quality of care delivered to patients. The activities of providers highlighted in this research represent the first steps ACO providers are taking to improve care; time will tell the extent to which these activities are the first of many that successfully alter the landscape of U.S. health care or are merely motion without substantial positive change.

Practice Implications

For those in newly formed ACOs or health care providers considering pursuing an ACO contract, this study provides empirical information on the common approaches to accountable care in the first year to a year and a half of ACO performance contracts. Although further research is needed to understand which activities most often result in achieving cost and quality performance, these results can provide a template for provider organizations of the basic activities many providers undertake when beginning an ACO. For example, providers may consider their capacity for undertaking primary care transformation or strengthening care management. In addition, our results might suggest that some providers who have not yet pursued ACOs because of considerations of complexity may in fact be considering a more complicated approach to accountable care than early ACOs; for example, our results suggest that most ACOs in early stage are not working to comprehensively transform specialty care or coordinate between acute and postacute care but instead are focused largely on primary care-based strategies. Thus, our results suggest that providers may not need to be concerned with those more complex issues prior to forming an ACO or undertaking an ACO contract.

Footnotes

The authors have disclosed that they have no significant relationship with, or financial interest in, any commercial companies pertaining to this article.

References

- Bao Y., Casalino L. P., & Pincus H. A. (2013). Behavioral health and health care reform models: Patient-centered medical home, health home, and accountable care organization. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 40(1), 121–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein S. J. (2013). Accountable care organizations and the practice of oncology. Journal of Oncology Practice, 9(3), 122–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien A. T., Song Z., Chernew M. E., Landon B. E., McNeil B. J., Safran D. G., & Schuster M. A. (2014). Two-year impact of the alternative quality contract on pediatric health care quality and spending. Pediatrics, 133(1), 96–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colla C. H., Goodney P. P., Lewis V. A., Nallamothu B. K., Gottlieb D. J., & Meara E. (2014). Implementation of a pilot accountable care organization payment model and the use of discretionary and non-discretionary cardiovascular care. Circulation, 130(22), 1954–1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colla C. H., Lewis V. A., Bergquist S. L., & Shortell S. M. (2016). Accountability across the continuum: The participation of postacute care providers in accountable care organizations. Health Services Research, 51(4), 1595–1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colla C. H., Lewis V. A., Kao L. S., O'Malley A. J., Chang C. H., & Fisher E. S. (2016). Association between Medicare accountable care organization implementation and spending among clinically vulnerable beneficiaries. JAMA Internal Medicine, 176(8), 1167–1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colla C. H., Lewis V. A., Tierney E., & Muhlestein D. B. (2016). Hospitals participating in ACOs tend to be large and urban, allowing access to capital and data. Health Affairs, 35(3), 431–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deremo D., Reese M., Block S. D., Jackson V. A., Lee T. H., Bishop L., & Sawicki R. (2014). Models of care delivery and coordination: Palliative care integration within accountable care organizations. In Kelley & A. S., Meier D. E., Meeting the needs of older adults with serious illness, aging medicine (pp. 153–176). New York, NY: Springer; Retrieved from http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4939-0407-5_11 [Google Scholar]

- Dupree J. M., Patel K., Singer S. J., West M., Wang R., Zinner M. J., & Weissman J. S. (2014). Attention to surgeons and surgical care is largely missing from early Medicare accountable care organizations. Health Affairs, 33(6), 972–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein A. M., Jha A. K., Orav E. J., Liebman D. L., Audet A. M., Zezza M. A., & Guterman S. (2014). Analysis of early accountable care organizations defines patient, structural, cost, and quality-of-care characteristics. Health Affairs, 33(1), 95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittell J. H. (2002). Coordinating mechanisms in care provider groups: Relational coordination as a mediator and input uncertainty as a moderator of performance effects. Management Science, 48(11), 1408–1426. [Google Scholar]

- Gittell J. H., Seidner R., & Wimbush J. (2010). A relational model of how high-performance work systems work. Organization Science, 21(2), 490–506. [Google Scholar]

- Gittell J. H., & Weiss L. (2004). Coordination networks within and across organizations: A multi-level framework. Journal of Management Studies, 41(1), 127–153. [Google Scholar]

- Goodney P. P., Fisher E. S., & Cambria R. P. (2012). Roles for specialty societies and vascular surgeons in accountable care organizations. Journal of Vascular Surgery, 55(3), 875–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homer C. J., & Patel K. K. (2013). Accountable care organizations in pediatrics: Irrelevant or a game changer for children? JAMA Pediatrics, 167(6), 507–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joynt K. E. (2014). The importance of specialist engagement in accountable care organizations. Circulation, 130(22), 1933–1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis V. A., Colla C. H., Schoenherr K. E., Shortell S. M., & Fisher E. S. (2014). Innovation in the safety net: Integrating community health centers through accountable care. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 29(11), 1484–1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis V. A., Colla C. H., Schpero W. L., Shortell S. M., & Fisher E. S. (2014). ACO contracting with private and public payers: A baseline comparative analysis. The American Journal of Managed Care, 20(12), 1008–1014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis V. A., Colla C. H., Tierney K., Van Citters A. D., Fisher E. S., & Meara E. (2014). Few ACOs pursue innovative models that integrate care for mental illness and substance abuse with primary care. Health Affairs, 33(10), 1808–1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maust D. T., Oslin D. W., & Marcus S. C. (2013). Mental health care in the accountable care organization. Psychiatric Services, 64(9), 908–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald K. M., Vandana S., Bravata D. M., Lewis R., Lin N., Kraft S, A., … Owens D. K. (2007). Closing the Quality Gap: A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies: Care Coordination (Vol. 7) Technical Reviews 9.7. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams J. M. (2014). Accountable care organizations: A challenging opportunity for primary care to demonstrate its value. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 29(6), 830–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams J. M., Chernew M. E., Landon B. E., & Schwartz A. L. (2015). Performance differences in year 1 of pioneer accountable care organizations. The New England Journal of Medicine, 372(20), 1927–1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams J. M., Chernew M. E., Zaslavsky A. M., & Landon B. E. (2013). Post-acute care and ACOs—Who will be accountable? Health Services Research, 48(4), 1526–1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams J. M., Hatfield L. A., Chernew M. E., Landon B. E., & Schwartz A. L. (2016). Early performance of accountable care organizations in Medicare. The New England Journal of Medicine, 374(24), 2357–2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams J. M., Landon B. E., Chernew M. E., & Zaslavsky A. M. (2014). Changes in patients’ experiences in medicare accountable care organizations. The New England Journal of Medicine, 371(18), 1715–1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morden N. E., Schwartz L. M., Fisher E. S., & Woloshin S. (2013). Accountable prescribing. The New England Journal of Medicine, 369(4), 299–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rundall T. G., Wu F. M., Lewis V. A., Schoenherr K. E., & Shortell S. M. (2016). Contributions of relational coordination to care management in accountable care organizations: Views of managerial and clinical leaders. Health Care Management Review, 41(2), 88–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortell S. M., Wu F. M., Lewis V. A., Colla C. H., & Fisher E. S. (2014). A taxonomy of accountable care organizations for policy and practice. Health Services Research, 49(6), 1883–1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M., Bates D. W., & Bodenheimer T. S. (2013). Pharmacists belong in accountable care organizations and integrated care teams. Health Affairs, 32(11), 1963–1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Z., Rose S., Safran D. G., Landon B. E., Day M. P., & Chernew M. E. (2014). Changes in health care spending and quality 4 years into global payment. The New England Journal of Medicine, 371(18), 1704–1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]