Abstract

Evidence supports the theory that bacterial communities colonizing Echinacea purpurea contribute to the innate immune enhancing activity of this botanical. Previously we reported that only about half of the variation in in vitro monocyte stimulating activity exhibited by E. purpurea extracts could be accounted for by total bacterial load within the plant material. In the current study we test the hypothesis that the type of bacteria, in addition to bacterial load, is necessary to fully account for extract activity. Bacterial community composition within commercial and freshly harvested (wild and cultivated) E. purpurea aerial samples was determined using high-throughput 16S rRNA gene pyrosequencing. Bacterial isolates representing 38 different taxa identified to be present within E. purpurea were acquired and the activity exhibited by extracts of these isolates varied by over 8,000-fold. Members of the Proteobacteria exhibited the highest potency for in vitro macrophage activation and were the most predominant taxa. Furthermore, the mean activity exhibited by the Echinacea extracts could be solely accounted for by the activities and prevalence of Proteobacteria members comprising the plant-associated bacterial community. The efficacy of E. purpurea material for use against respiratory infections may be determined by the Proteobacterial community composition of this plant, since ingestion of bacteria (probiotics) is reported to have a protective effect against this health condition.

Keywords: Echinacea purpurea, immunostimulatory, macrophage activation, bacteria, Proteobacteria, endophytes

Introduction

Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench (Asteraceae) is a popular immune enhancing botanical in Europe and North America and is used in the prevention and treatment of upper respiratory tract infections [1]. Research demonstrates that Echinacea exhibits both anti-inflammatory and immunostimulatory therapeutic actions. Alkylamides [2] represent anti-inflammatory components within Echinacea and therefore could offer symptomatic relief for colds and flu similar to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. A growing body of literature indicates that variation in the amount and type of bacteria colonizing E. purpurea is responsible for the differences in the immunostimulatory potential of Echinacea plant material. Ingestion of Echinacea containing high levels of immunostimulatory bacterial components may activate the innate immune system and exert therapeutic actions against respiratory infections similar to those observed in clinical studies using probiotic bacteria [reviewed in 3].

We have reported that 97% of the monocyte/macrophage activation potential exhibited by extracts of Echinacea arose from the presence of the bacterial components, lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and Braun-type lipoproteins [4]. High levels of these two bacterial components were found to be present within commercially obtained bulk plant material of E. purpurea and E. angustifolia sourced from six major growers/commercial suppliers in North America. Substantial variation in activity (up to 200-fold) was observed in extracts from these commercial materials, and the activity was negated by treatment with lipoprotein lipase (removes ester-linked fatty acids from the glycerol of Braun-type lipoproteins) and polymyxin B (an inhibitor of LPS) [5]. Other researchers have recently reported that the macrophage simulating activity (TNF-alpha production from RAW 264.7 cells) and the LPS content of 75% ethanol extracts of E. purpurea are derived from endophytic bacteria [6]. Extracts of E. purpurea plants grown under sterile conditions (from seeds sterilized after removal of the epidermis) did not activate macrophages and contained very low levels of LPS as compared to a control plant that was only surface sterilized (surface bacteria removed but endophytic bacteria preserved). Together, the above studies suggest components derived from endophytic bacteria within Echinacea contribute substantially to the in vitro activation of macrophages by extracts of this plant.

In our prior research, total bacterial load within samples of E. purpurea tissue ranged between 106 and 108 bacterial cells/g of dry material. Although bacterial load was strongly correlated with in vitro monocyte activation, only about 54% of the variation in immune enhancing activity exhibited by the Echinacea extracts could be accounted for by bacterial load [7]. Therefore, the objective of the current study was to evaluate the hypothesis that variation in the type of bacteria, together with bacterial load, can more completely account for the activity of the plant material. To accomplish this objective, we identified and isolated bacteria associated with tissue of E. purpurea and evaluated extracts of these isolates for their ability to activate macrophages in vitro. Activity of each plant extract was then compared to the sum of the activities contributed by the amount of each bacterial taxa contained in the plant material.

Results

Total bacterial load varied 36-fold (6.4×106 to 2.3×108, Table 1) for samples from commercial material as compared with only 2.6-fold (4.9×106 to 1.3×107, Table 1) for samples from freshly harvested material. Similarly, activity (EC25 values) varied 72-fold (49 to 3511μg plant material/mL) and 6.8-fold (495 to 3358μg plant material/mL) for extracts from commercial and freshly harvested material, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

The amount of in vitro macrophage stimulatory activity exhibited by Echinacea purpurea that is from plant associated bacteria. E. purpurea aerial material was obtained from fresh wild and cultivated plants and from dried material from six commercial growers. “Percent of activity due to” Total bacteria or Proteobacteria represents the percent of macrophage stimulatory activity exhibited by an E. purpurea extract that can be accounted for by the sum of the activities contributed by the specified bacterial taxa contained in that plant material.

| Load (× 106) | Activity | Percent of activity due to: | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total bacteria | Proteobacteria | (EC25)a | Total bacteria | Proteobacteria | |

| Freshly harvested | |||||

| Plant 1 (wild) | 7.8 | 6.0 | 2057 | 104 | 104 |

| Plant 2 (wild) | 7.3 | 5.7 | 1283 | 91 | 90 |

| Plant 3 (wild) | 8.6 | 6.7 | 617 | 132 | 131 |

| Plant 4 (wild) | 12.7 | 10.5 | 602 | 96 | 95 |

| Plant 1 (cultivated) | 4.9 | 2.4 | 3358 | 72 | 67 |

| Plant 2 (cultivated) | 8.7 | 5.1 | 495 | 29 | 28 |

| Plant 3 (cultivated) | 6.2 | 4.7 | 2120 | 89 | 88 |

| Plant 4 (cultivated) | 10.1 | 7.1 | 980 | 83 | 81 |

| Commercial material | |||||

| Company A | — | — | 1638 | — | — |

| Company B | 19.2 | 10.4 | 3511 | 361 | 349 |

| Company C | 6.4 | 4.0 | 431 | 26 | 26 |

| Company D | 25.0 | 9.7 | 633 | 104 | 91 |

| Company E | 62.6 | 40.0 | 184 | 97 | 96 |

| Company F | 230.5 | 127.9 | 49 | 83 | 82 |

| Mean (SE) | 31.5 (17.1) | 18.5 (9.5) | 1283 (298) | 105 (22.8) | 102 (22.0) |

EC25 value represents the concentration (μg/mL) of plant material required to induce TNF-alpha production in RAW 264.7 cells to levels 25% of those achieved by ultra pure LPS (100ng/mL).

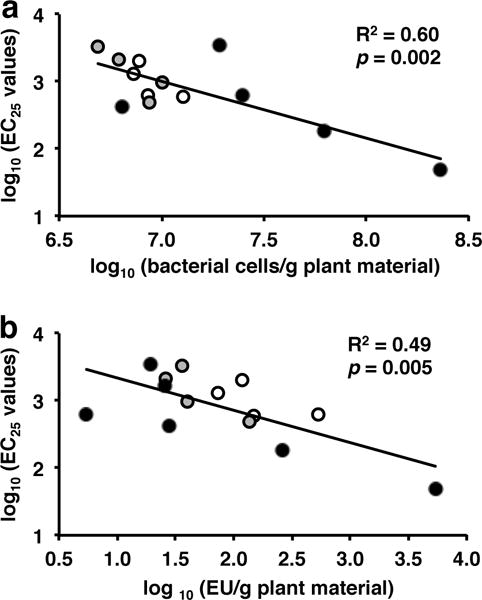

In vitro macrophage stimulatory activity (TNF-alpha production from RAW 264.7 cells) exhibited by E. purpurea aerial samples was significantly correlated with the estimated total load of bacterial cells (R2 = 0.60, p = 0.002, Fig. 1a). Content of LPS as determined by the LAL assay was significantly correlated with in vitro macrophage stimulatory activity (R2 = 0.49, p = 0.005, Fig. 1b). Results from the present study corroborate our previous data [7] that total bacteria load present within E. purpurea (commercially sourced roots and aerial material) was also correlated with the potency of monocyte activation (nuclear factor kappa B activation in THP-1 monocytes).

Fig. 1.

Correlations of in vitro macrophage stimulatory activity exhibited by extracts from Echinacea purpurea with bacterial load and LPS content within aerial plant material. Plant material was obtained from wild E. purpurea (white circles), cultivated E. purpurea (gray circles) and dried material from commercial growers (black circles). Plant material was extracted with 4% SDS and extracts evaluated for activity (TNF-alpha production) in RAW 264.7 macrophages (EC25 values of extracts are in μg of plant material/mL). LPS content (EU/g of dried plant material) was determined through the Pyrochrome®-LAL assay with Glucashield®. Total bacterial load was estimated using a PCR-based quantification method [7]. Pairwise linear regressions are between macrophage stimulatory extract activity and total bacterial load of plant material (a), and macrophage stimulatory activity and LPS levels in extracts (b). Regression analyses were performed on log10 transformed data using Microsoft Excel 2007 and 2011.

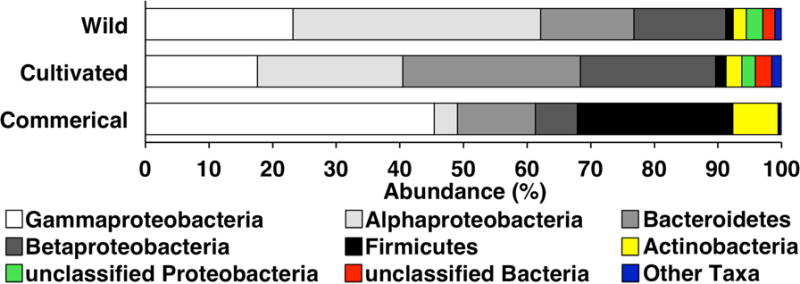

Bacterial community composition within E. purpurea samples was determined using high-throughput 16S rRNA gene pyrosequencing. Of the 14 samples analyzed, one did not yield enough intact DNA to allow for sequencing; therefore, 13 samples were used in the pyrosequencing analysis. Community composition varied between the different sources of Echinacea material, although the majority of bacteria identified were consistently Proteobacteria, making up 55.9, 64.4 and 79.5% of the sequences recovered from commercial, wild and cultivated samples, respectively. Differences between sample types became more apparent at the subphylum level (Fig. 2). Gammaproteobacteria was the most abundant subphyla in commercial samples (45.4% of bacterial sequences recovered), but only made up 23.3 and 17.6% of bacteria identified in wild and cultivated Echinacea tissue, respectively. In contrast, Alphaproteobacteria was the most abundant subphylum in wild (39% of total) and cultivated (22.9%) tissues but only accounted for 3.6% of the community in commercial samples. Betaproteobacteria also composed a larger proportion of the communities in wild (14.4%) and cultivated (21.3%) samples compared to commercial Echinacea material (6.6%). Differences between sample types were also noted in other abundant phyla. Cultivated Echinacea contained the greatest relative abundance of Bacteroidetes (27.9% compared to 14.6% and 12.3% in wild and commercial samples), while Firmicutes were over 14 times more abundant in commercial than in fresh samples (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Mean bacterial community structure in E. purpurea aerial material. Plant material was obtained from wild communities (4 samples), cultivation (4 samples) and commercial growers (6 samples). “Other Taxa” constitute between 0.3% and 1.5% of the community and include Deinococcus-Thermus, Deltaproteobacteria, Candidate division TM7, Planctomycetes, Acidobacteria, Cyanobacteria, Fusobacteria, Candidate division OP10, Gemmatimonadetes, Chlamydiae, Verrucomicrobia, Fibrobacteres, Candidatus Thiobios, and Chloroflexi.

Initially, 120 bacterial isolates were obtained by plating homogenized fresh plant tissue. However, many of these isolates were redundant and the 120 isolates represented only 27 distinct taxa based on 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Comparing isolate taxonomy to whole community sequencing of commercial samples, several taxa were detected by community sequencing that did not have a closely related isolate from the fresh plant material. We obtained isolates for each of those taxa from culture depositories so that a total of 38 different bacterial isolates (27 E. purpurea isolates, 11 depository isolates; Table 2) were assayed for activity (TNF-alpha production from RAW 264.7 cells) in 4% SDS extracts. Activity of the different isolates varied by over 8000-fold, with Gram-negative isolates belonging to phylum Proteobacteria being the most potent stimulators of in vitro macrophage activation (lowest EC25 values; Table 2). Isolates classified as members of the Actinobacteria or Bacteroidetes exhibited moderate potency, while members of the Firmicutes (exclusively Gram-positive) exhibited low potency (Table 2).

Table 2.

Variation in in vitro macrophage stimulatory activity of extracts from bacterial isolates obtained from fresh Echinacea purpurea aerial material or from culture collections. Isolates are named based on the finest resolution of identification obtained from partial 16S rRNA gene sequencing and the affiliated bacterial phylum noted along with whether that taxon is Gram positive or Gram negative. Isolates from culture collections represent taxa identified within E. purpurea samples by whole community 16S rRNA gene sequencing but not directly isolated from that material. Members of the Proteobacteria phylum are indicated by shaded rows.

| Bacterial Isolate | Activity (EC25)a | Bacterial Phylum |

|---|---|---|

| Rhizobium | 216 | Proteobacteria (Gram-negative) |

| Acidovorax delafieldiib | 295 | Proteobacteria (Gram-negative) |

| Roseomonas | 646 | Proteobacteria (Gram-negative) |

| Erwinia | 831 | Proteobacteria (Gram-negative) |

| Agrobacterium | 832 | Proteobacteria (Gram-negative) |

| Citrobacter amalonaticusb | 842 | Proteobacteria (Gram-negative) |

| Pseudoxanthomonas | 1240 | Proteobacteria (Gram-negative) |

| Enterobacter | 1790 | Proteobacteria (Gram-negative) |

| Pseudomonas | 2150 | Proteobacteria (Gram-negative) |

| Stappia stellulata | 2260 | Proteobacteria (Gram-negative) |

| Stenotrophomonas | 3130 | Proteobacteria (Gram-negative) |

| Sphingopyxis | 3230 | Proteobacteria (Gram-negative) |

| Sphingobium | 4590 | Proteobacteria (Gram-negative) |

| Flavobacterium | 6590 | Bacteroidetes (Gram-negative) |

| Variovorax | 6760 | Proteobacteria (Gram-negative) |

| Aeromicrobium | 8650 | Actinobacteria (Gram-positive) |

| Blastococcus | 9010 | Actinobacteria (Gram-positive) |

| Sphingomonas | 9620 | Proteobacteria (Gram-negative) |

| Novosphingobium | 15800 | Proteobacteria (Gram-negative) |

| Nocardioides | 16800 | Actinobacteria (Gram-positive) |

| Bosea | 17700 | Proteobacteria (Gram-negative) |

| Chryseobacterium | 18200 | Bacteroidetes (Gram-negative) |

| Frigoribacterium | 19100 | Actinobacteria (Gram-positive) |

| Rathayibacter | 21000 | Actinobacteria (Gram-positive) |

| Hymenobacter deserti | 21600 | Bacteroidetes (Gram-negative) |

| Kineococcus | 37800 | Actinobacteria (Gram-positive) |

| Carnobacterium gallinarumb | 62600 | Firmicutes (Gram-positive) |

| Paenibacillus | 81386 | Firmicutes (Gram-positive) |

| Pedobacter heparinusb | 99900 | Bacteroidetes (Gram-negative) |

| Microbacterium | 166000 | Actinobacteria (Gram-positive) |

| Mucilaginibacter soli | 265000 | Bacteroidetes (Gram-negative) |

| Pedobacter xinjiangensisb | 289000 | Bacteroidetes (Gram-negative) |

| Lysinibacillus | 292000 | Firmicutes (Gram-positive) |

| Bacillus | 775242 | Firmicutes (Gram-positive) |

| Exiguobacterium aurantiacumb | 1270000 | Firmicutes (Gram-positive) |

| Carnobacterium divergensb | 1770000 | Firmicutes (Gram-positive) |

| Arthrobacter | inactive | Actinobacteria (Gram-positive) |

| Curtobacterium flaccumfaciensb | inactive | Actinobacteria (Gram-positive) |

EC25 value represents the number of bacteria (added/well) capable of inducing TNF-alpha production in RAW 264.7 cells to 25% activation. Percent activation is the level of TNF-alpha production expressed as a percent relative to levels achieved by ultra pure LPS tested at 100ng/mL. Inactive is defined as extracts that when tested at the highest concentration induced TNF-alpha production to levels less than 4% (control values for untreated cells ranged between 0.3% and 0.8%).

Bacterial isolates obtained from culture collections.

Based on our data there are two factors that determine the in vitro activity exhibited by extracts of E. purpurea plant material. The first is the total bacterial load present within the plant material (Fig. 1a; 7). The second is the activity exhibited by each specific type of bacteria present within the plant material (Table 2). Combining these two factors yields the percent of activity exhibited by each plant extract that can be accounted for by its specific bacterial community. While there was variation across samples, taken together the sum of activities contributed by the prevalence and types of bacteria within E. purpurea aerial material accounted for the mean activity exhibited by the extracts (Table 1). Furthermore, the mean activity exhibited by the E. purpurea extracts could be fully accounted for solely by members of the Proteobacteria (Table 1). The percent of extract activity contributed by Proteobacteria in each sample was due to either a single subphylum (alpha, gamma) or a combination of subphyla (alpha, beta and gamma; Table 1S). Only taxa that accounted for >2% of the sequences in the whole community of at least one sample were used in the calculations, but expanding the number of taxa to include those that accounted for >0.5% of the sequences did not change the results (data not shown). Twenty-eight taxa had sequences accounting for >2% of the bacterial community in the commercial E. purpurea samples, two-thirds of which were classified as Gram negative (Table 2S). Together these taxa accounted for 69%–87% of the bacterial load. For the wild and cultivated E. purpurea, 27 bacterial taxa (25 Gram negatives) had sequences accounting for >2% of the community in at least one sample, and together these taxa comprised 78%–89% of the bacterial load (Table 3S).

Discussion

Our earlier research indicated that bacteria associated with E. purpurea are the source of components (Braun-type lipoproteins and LPS) responsible for 97% of the in vitro macrophage activation exhibited by extracts of this botanical [4]. However, further research [7] demonstrated that although the total bacterial load within E. purpurea material is significantly correlated with in vitro monocyte stimulating activity, only 54% of the variation in activity could be accounted for by the amount of bacteria. Therefore, we hypothesized that the type of bacteria, in addition to bacterial load, is necessary to fully account for the degree of in vitro macrophage activation exhibited by E. purpurea plant material. In the current study, we obtained bacterial isolates representing 38 different taxa that were identified to be present within E. purpurea and found the activity exhibited by extracts of these isolates varied by over 8000-fold. Supporting our hypothesis, we further demonstrated the sum of activities calculated from the prevalence of each isolate within the E. purpurea aerial material accounted for the in vitro activity exhibited by extracts of these samples.

The substantial variation in activity observed among extracts of different bacterial isolates indicates that the type of bacteria present in E. purpurea is an important factor contributing to the overall in vitro macrophage activation potential of this botanical. Since members of the Proteobacteria exhibited the highest potency for macrophage activation and were the most predominant taxa, it is likely that bacteria of this phyla are responsible for the majority of the activity exhibited by E. purpurea aerial plant material. However, the specific types of Proteobacteria within E. purpurea is also an important factor, since the activity exhibited by extracts of bacteria in this phylum still varied by almost two orders of magnitude. The significant correlation between LPS content and activity found here and in prior studies [7] is further evidence supporting the importance of Proteobacteria, as members of this phylum are Gram-negative and therefore contain LPS as a major cellular component. The mean in vitro activity exhibited by the E. purpurea extracts can be accounted for by the activities and prevalence of Proteobacteria alone, substantiating that components from Proteobacteria are responsible for the in vitro macrophage activation exhibited by extracts of E. purpurea aerial material. A similar finding was recently reported by Montenegro et al. [8] who found Proteobacteria of the genus Rahnella was the most abundant taxa in the root material from Angelica sinensis, and its prevalence was correlated with in vitro macrophage activation by extracts of this plant.

To determine the amount of plant extract activity that can be accounted for by the bacteria colonizing E. purpurea, we calculated the total activity contributed by each bacterial taxa detected within the plant material, an approach that has potential limitations. Some bacterial isolates could only be identified to the genus level rather than species, an outcome of both short (typically 400–500 bp) read lengths and incomplete taxonomy databases. If there are substantial differences in activity between species of the same genus (or even between strains of the same species), this would not have been accounted for in our calculations. It is also possible that bacterial isolates grown in culture could exhibit different levels of activity compared to the same bacterium growing within the plant material. Assay protocols used to estimate bacterial load and activity (EC25 values) could also have led to errors in the final calculations. These variables might explain why the percentage of plant extract activity accounted for by the total bacteria colonizing E. purpurea varied substantially. However, despite these potential limitations, >80% of the E. purpurea extract activity was accounted for in 10 of the 13 samples tested, and the mean of all samples (105%) suggests that bacterial isolates can fully account for the plant activity.

To mimic commercial processing, the fresh E. purpurea aerial material was not washed prior to analysis and therefore could have contained both epiphytic (surface associated) and endophytic bacteria. For the cultivated and wild populations of E. purpurea, post-harvest growth or introduction of contaminating bacteria or fungi was not an issue, since plants were immediately frozen after harvest. Commercial plant material was obtained from growers/suppliers, so it is possible that post-harvest bacterial contamination contributed to the total bacterial load detected. However, we have previously demonstrated that various postharvest drying procedures do not significantly influence extract activity [5]. Extracts of plant material from cultivated and wild populations of E. purpurea (harvested under control conditions) exhibited activity and LPS levels within the same range as that observed for commercial samples, so any post-contamination of commercial samples was likely minimal.

Greater variability was observed in the total bacterial load and macrophage stimulating activity exhibited by commercial samples compared to those that were freshly harvested. Substantial differences were also observed in the bacteria identified from commercial compared to freshly harvested tissue. At the phylum level, both Firmicutes and Actinobactera were more abundant in commercial than wild or cultivated samples. At the genus level, Pseudomonas (Gram negative) was the most abundant genera identified in commercial samples, but made up <3% of the community in all but one of the wild and commercial samples. The diverse sources (from locations throughout North America) as well as other potential characteristics (plant age at harvest and time in storage) of the commercially obtained Echinacea material may explain the differences observed between these samples and the freshly harvested plant samples.

The bacteria identified in our samples include several that have been identified by previous culture-based studies of Echinacea associated bacteria. For example, the two most abundant genera identified in commercial samples (Pseudomonas and Pantoea) have also been identified among isolates from aerial Echinacea tissue [9, 10]. The most abundant genus identified in wild Echinacea plants, Methylobacterium, was also identified in these two studies [9, 10]. However, some highly abundant bacteria identified in the current study (e.g. Hymenobacter in the cultivated samples) were not detected in culture-based studies [9, 10, 11]. Although culture bias may explain some of the community differences observed between our research and previous studies, experiments on produce-associated bacteria suggest the most prevalent bacteria in a sample (as identified through community sequencing) can often be isolated by culture-based methods [12]. Given the variability in abundance of dominant bacterial groups identified between samples in the current study and the geographic differences in sampling location (North America in the current study and Italy [9, 10]), it is likely that many of the differences in Echinacea-associated bacteria identified between our research and previous studies are genuine.

Macrophage activation (TNF-alpha production by RAW 264.7 cells) was used in the current study to evaluate extracts of E. purpurea and bacterial isolates since activity detected from in vitro activation of innate immune cells appears to be predictive of in vivo efficacy. For example, protection against influenza viral infection in mice was observed after oral administration of a Lactobacillus plantarum strain inducing high cytokine production in vitro, whereas no protection was observed for stains exhibiting inhibition or low cytokine production [13]. Similarly, we have reported that a botanical extract enriched for the bacterial component Braun-type lipoproteins exhibited potent activation of macrophages in vitro and that oral ingestion of this extract in mice exhibited a protective effect against influenza (H1N1) viral infection [14]. In human clinical trials using probiotics for prevention of respiratory infections, evidence indicates strains of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium can reduce the duration of illness in children and adults [reviewed in 3]. Based on the above studies we hypothesize that ingestion of the bacteria colonizing Echinacea plant material may mediate similar therapeutic effects against respiratory infections. In the current study, we provide evidence that the most predominant taxa colonizing Echinacea plant material are members of the Proteobacteria that are potent in vitro activators of macrophage function. A normal dose of Echinacea plant material contains a typical bacterial load that is comparable to a therapeutic dose of probiotic bacteria [7].

Clinical trials evaluating the potential health benefits of E. purpurea dietary supplements for preventing and/or treating the common cold have produced inconsistent results [15]. A major problem contributing to the inconsistent outcomes of Echinacea clinical trials is that these studies have used many different products. These products have varied with respect to plant species (E. purpurea, E. angustifolia and E. pallida), plant part (aerial, flower, root and whole) and raw material (sourced from different climatic areas). As previously shown in commercially diverse bulk Echinacea material, the level of in vitro monocyte/macrophage activation due to bacterial components (LPS and Braun-type lipoproteins) varied by up to 200-fold [5], and the total bacterial load varied by 52-fold [7]. Thus it is possible that the level of activity due to bacterial components varied substantially among the products that have been used in prior Echinacea clinical trials and may have contributed to the inconsistent outcomes of those trials.

Materials and Methods

Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench plant material

Bulk aerial material for E. purpurea was obtained from the following six commercial suppliers: Frontier Natural Products Co-op (lot number 769.3052), Gaia Herbs (lot number 00033507), Glenbrook Farms Herbs & Such (lot number not available), Mountain Rose Herbs (lot number 12066), Richters (lot number 21580), and Trout Lake Farm LLC (lot number EPH-S2051-E3P).

E. purpurea is regularly cultivated on campus at The University of Mississippi and this served as a source to obtain four individual mature/flowering plants for analysis of freshly harvested material. An additional four plants were collected from wild populations at two sites within Mark Twain National Forest, Missouri, USA, by trained botanists (V. Maddox and R. Moraes). For all cultivated and wild plants, fresh aerial material was harvested in July 2012 and immediately freeze-dried to prevent post-harvest growth or introduction of bacteria. Dried plant material was ground and stored at −20°C until use.

Voucher specimens for commercially sourced and cultivated E. purpurea plant samples were deposited in the NCNPR repository at The University of Mississippi. Voucher specimens (numbers 5582 and 5583) for E. purpurea plants collected from wild communities were deposited at Mississippi State University.

Bacterial isolates from fresh plant material and culture depositories

Two E. purpurea plants were collected from the east side of the National Center for Natural Products Research Center on the University of Mississippi campus. Approximately 5 g of root and aerial tissue was collected from each plant and rinsed twice with sterile water. Each 5 g root or aerial tissue sample was added to sterile 100 mL phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and homogenized. The homogenizer was cleaned between samples by running it twice with RO water, rinsed with 70% ethanol to sterilize, and rinsed one final time with sterile water. Homogenates were serially diluted in sterile PBS and 100 μL from each dilution spread on petri dishes containing the following media: tryptic soy agar, nutrient agar, and R2A agar. Two plates were spread per dilution and media type. Plates were incubated at 25°C and checked for new colonies every 24 hours until no new growth was determined. Colonies with a variety of morphologies were selected and streaked for isolation. Isolates were maintained on the media from which they were initially cultured. Additional bacterial genera identified in sequence analysis of Echinacea samples were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and the US Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service’s Northern Regional Research Laboratory (USDA-ARS NRRL) Culture Collection (Table 3).

Table 3.

Bacterial isolates obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and US Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service’s Northern Regional Research Laboratory (USDA-ARS NRRL) Culture Collection. Selected isolates were from genera identified in commercial Echinacea samples by sequence analysis but not obtained from culturing fresh Echinacea tissue.

| Species | Source | Catalog # |

|---|---|---|

| Acidovorax delafieldii | USDA-ARS NRRL | B-4387 |

| Carnobacterium divergens | USDA-ARS NRRL | B-23835 |

| Carnobacterium gallinarum | USDA-ARS NRRL | B-14832 |

| Citrobacter amalonaticus | USDA-ARS NRRL | B-41228 |

| Curtobacterium flaccumfaciens | USDA-ARS NRRL | B-729 |

| Exiguobacterium aurantiacum | ATCC | 35652 |

| Hymenobacter deserti | USDA-ARS NRRL | B-51267 |

| Mucilaginibacter soli | USDA-ARS NRRL | B-59458 |

| Pedobacter heparinus | USDA-ARS NRRL | B-14731 |

| Pedobacter xinjiangensis | USDA-ARS NRRL | B-51338 |

| Stappia stellulata | ATCC | 15215 |

Identification of bacterial isolates

DNA from colonies of each isolate was amplified using primers for the 16S rRNA gene, Bac8F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and Univ1492R (5′-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′). Reactions contained 50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3 at 25°C), 1.5 mM Mg2+, 0.4 μM each primer, 200 μM each dNTP, and 1.25 U Taq polymerase in a final volume of 50 μL. Template was added by touching an isolated colony of each isolate with a sterile toothpick and dipping the toothpick in the reaction mix. Amplifications were performed using the following cycle: initial denaturation at 95°C for 6 min, followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 45°C for 1 min, 72°C for 2 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. Isolates that did not amplify using colony PCR were cultured on their respective media and DNA was extracted using UltraClean Microbial DNA isolation kits (MoBio) following manufacturer’s instructions. Amplifications from DNA extracts were performed as described above, except using 2 μL of extract as template and a shorter initial denaturation of 2 min at 95°C. Amplification products (approximately 600 bp in length) were sequenced through a commercial facility (Functional Biosciences). Resulting DNA sequences were trimmed and identified to the genus level by comparing against sequences in GenBank using BLAST.

Extraction of E. purpurea aerial material and bacterial isolates for analysis of activity and content of LPS

Crude biochemical extracts were prepared from the E. purpurea plant samples by extraction with 98°C water containing 4% SDS as previously described [7]. Bacterial isolates were cultured in broth to an optical density of 0.5 or greater and then 60 μL removed for extraction. The entire 60 μL was used for extraction to include both bacterial cells and secreted bacterial components in the culture medium. SDS was added to each 60 μL sample to a final concentration of 4% and the sample extracted at 98°C for 1 hour. Following removal of SDS using SDS-out reagent (Pierce) in the presence of 1% octylglucoside, crude bacterial extracts were assessed for macrophage activity.

Determination of TNF-alpha production from macorphages and limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL) assay

Macrophage activation was determined by measuring TNF-alpha production from RAW 264.7 cells incubated with extracts of plants and bacterial isolates for 18–24 h as previously described [14]. Level of TNF-alpha in the culture supernatants was determined using ELISA (R&D Systems) following manufacturer’s protocol. Macrophage activation for plant material is reported as an EC25 value that represents the concentration (μg/mL) of plant material required to induce TNF-alpha production to 25% of levels achieved by ultra pure E. coli LPS 0111:B4 strain (InvivoGen) tested at 100ng/mL. Activity of each bacterial isolate is also reported as an EC25 value and represents the number of bacteria (added/well) that induce TNF-alpha production to 25% of levels achieved by ultra pure LPS.

LPS content in the plant 4% SDS crude extracts was determined using the Pyrochrome® LAL assay with Glucashield® (1→3)-β-D-Glucan Inhibiting Buffer (Associates of Cape Cod, Inc.). Glucashield® reagent blocks the contribution of (1→3)-β-D-glucans in the LAL reaction. The use of this reagent is crucial during the analysis of plant extracts since trace levels of glucans present from cellulosic material and from fungal/bacterial origin can interfere with accurate detection of LPS. Data is reported as endotoxin units (EU/g of dried plant material).

Estimation of plant total bacterial load

Total bacterial load was determined through a PCR-based method as described previously [7]. DNA was extracted from 200 mg of commercial E. purpurea samples using PowerSoil DNA isolation kits (MoBio). DNA from greenhouse cultivated and wild E. purpurea was extracted from 50 mg of tissue using PowerPlant Pro DNA isolation kits (MoBio). Prior to extraction, commercial samples were hydrated with 800 μL sterile water, and cultivated and wild samples were rehydrated with 150 μL sterile water. Following extraction, samples were cleaned using PowerClean DNA Cleanup Kits (MoBio) to remove PCR inhibitors. A portion of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified using primers 799f (5′-AACMGGATTAGATACCCKG-3′) and 1492r (5′-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′) that exclude the coamplification of chloroplast DNA [16]. These primers yield a 735 bp bacterial product and a 1090 bp mitochondrial product when used to amplify DNA extracted from plant material [16]. DNA amplifications were conducted as previously described [7]. Bacterial loads were calculated by comparing the intensity of the 735 bp bacterial band from commercial and fresh E. purpurea extracts to a standard curve of DNA extracted and amplified from known quantities of bacteria as described previously [7].

Determination of bacterial community structure

Analysis of the bacterial community associated with E. purpurea was conducted on the same 16S rRNA PCR products used to determine total bacterial load. Bacterial DNA was isolated from the mitochondrial coamplification product by running PCR products on a 1.4% agarose, cutting out the 735 bp bacterial band, and extracting DNA using the Ultraclean GelSpin DNA Extraction kits (MoBio). Bacterial tag-encoded FLX amplicon 454 pyrosequencing (bTEFAP) [17] was conducted on the 16S rRNA 735 bp product of each sample, through a dedicated sequencing facility (MR DNA). Bacterial primers 939f and 1392r [18, 19] were used in the sequencing reaction. A single-step PCR using HotStarTaq Plus Master Mix Kit (Qiagen) was used under the following conditions: 94°C for 3 min, followed by 28 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 53°C for 40 sec, and 72°C for 1 min, with a final elongation step at 72°C for 5 min. Following PCR, all amplicon products from different samples were mixed in equal concentrations and purified using Agencourt AMPure XP beads (Agencourt Bioscience Corporation). Samples were sequenced using Roche 454 FLX titanium instruments and reagents following the manufacturer’s guidelines.

Raw pyrosequence data was transferred into FASTA files for each sample, along with sequencing quality files. Files were accessed using the bioinformatics software Mothur [20] where they were processed and analyzed following the procedures recommended by Schloss et al. [21]. Briefly, sequences were denoised and trimmed to remove barcodes and primers. Chimeric sequences were removed and sequences were then aligned and classified according to those in the SILVA rRNA database [22], after which any sequences classified as being other than bacterial were removed from the dataset. The cell load of each bacterial taxon in Echinacea samples were subsequently calculated from the proportion of sequencing reads of each taxon and the total bacterial load in each sample.

Statistical Analysis

Simple linear regressions were used to relate bacterial load to PCR product band intensity for the standard curve samples. These regressions were then used to determine bacterial load in plant extracts and bacterial isolate cultures based on PCR product band intensity.

Pairwise linear regressions were used to examine the relationships between bacterial load, macrophage activation and content of LPS in E. purpurea samples. Since values for each variable were not normally distributed and spanned several orders of magnitude, data were log10 transformed prior to regressions [23]. All transformations and regressions were conducted in Microsoft Excel 2011.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Information: Methods for: cultures to determine isolate activity; calculating total activity exhibited by the bacteria within the plant material.

Acknowledgments

This research was partly funded by Grant Number R01AT007042 from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) and the Office of Dietary Supplements (ODS). The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NCCIH, ODS or the National Institutes of Health. Additional funding of this research was also provided by grants from the USDA, Agricultural Research Service Specific Cooperative Agreement Nos. 58-6408-6-067 and 58-6408-1-603.

Abbreviations

- E. purpurea

Echinacea purpurea

- LPS

lipopolysaccharides

- EC

effective concentration

- LAL

limulus amebocyte lysate

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Karsch-Völk M, Barrett B, Kiefer D, Bauer R, Ardjomand-Woelkart K, Linde K. Echinacea for preventing and treating the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2:CD000530. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000530.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cech NB, Kandhi V, Davis JM, Hamilton A, Eads D, Laster SM. Echinacea and its alkylamides: effects on the influenza A-induced secretion of cytokines, chemokines, and PGE2 from RAW 264.7 macrophage-like cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2010;10:1268–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.King S, Glanville J, Sanders ME, Fitzgerald A, Varley D. Effectiveness of probiotics on the duration of illness in healthy children and adults who develop common acute respiratory infectious conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Nutr. 2014;112:41–54. doi: 10.1017/S0007114514000075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pugh ND, Tamta H, Balachandran P, Wu X, Howell J, Dayan FE, Pasco DS. The majority of in vitro macrophage activation exhibited by extracts of some immune enhancing botanicals is due to bacterial lipoproteins and lipopolysaccharides. Int Immunopharmacol. 2008;8:1023–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tamta H, Pugh ND, Balachandran P, Moraes R, Sumiyanto J, Pasco DS. Variability in in vitro macrophage activation by commercially diverse bulk Echinacea plant material is predominantly due to bacterial lipoproteins and lipopolysaccharides. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:10552–10556. doi: 10.1021/jf8023722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Todd DA, Gulledge TV, Britton ER, Oberhofer M, Leyte-Lugo M, Moody AN, Shymanovich T, Grubbs LF, Juzumaite M, Graf TN, Oberlies NH, Faeth SH, Laster SM, Cech NB. Ethanolic Echinacea purpurea extracts contain a mixture of cytokine-suppressive and cytokine-inducing compounds, including some that originate from endophytic bacteria. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0124276. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pugh ND, Jackson CR, Pasco DS. Total bacterial load within Echinacea purpurea, determined using a new PCR-based quantification method, is correlated with LPS levels and in vitro macrophage activity. Planta Med. 2013;79:9–14. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1328023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montenegro D, Kalpana K, Chrissian C, Sharma A, Takaoka A, Iacovidou M, Soll CE, Aminova O, Heguy A, Cohen L, Shen S, Kawamura A. Uncovering potential ‘herbal probiotics’ in Juzen-taiho-to through the study of associated bacterial populations. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2015;25:466–469. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiellini C, Maida I, Emiliani G, Mengoni A, Mocali S, Fabiani A, Biffi S, Maggini V, Gori L, Vannacci A, Gallo E, Firenzuoli F, Fani R. Endophytic and rhizospheric bacterial communities isolated from the medicinal plants Echinacea purpurea and Echinacea angustifolia. Int Microbiol. 2014;17:165–174. doi: 10.2436/20.1501.01.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mengoni A, Maida I, Chiellini C, Emiliani G, Mocali S, Fabiani A, Fondi M, Firenzuoli F, Fani R. Antibiotic resistance differentiates Echinacea purpurea endophytic bacterial communities with respect to plant organs. Res Microbiol. 2014;165:686–694. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lata H, Li XC, Silva B, Moraes RM, Halda-Alija L. Identification of IAA-producing endophytic bacteria from micropropagated Echinacea plants using 16S rRNA sequencing. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2006;85:353–359. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jackson CR, Randolph KC, Osborn SL, Tyler HL. Culture dependent and independent analysis of bacterial communities associated with commercial salad leaf vegetables. BMC Microbiol. 2013;13:274. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kechaou N, Chain F, Gratadoux JJ, Blugeon S, Bertho N, Chevalier C, Le Goffic R, Courau S, Molimard P, Chatel JM, Langella P, Bermúdez-Humarán LG. Identification of one novel candidate probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum strain active against influenza virus infection in mice by a large-scale screening. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:1491–1499. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03075-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pugh ND, Edwall D, Lindmark L, Kousoulas KG, Iyer AV, Haron MH, Pasco DS. Oral administration of a Spirulina extract enriched for Braun-type lipoproteins protects mice against influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. Phytomedicine. 2015;22:271–276. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manayi A, Vazirian M, Saeidnia S. Echinacea purpurea: Pharmacology, phytochemistry and analysis methods. Pharmacogn Rev. 2015;9:63–72. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.156353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chelius MK, Triplett EW. The diversity of Archaea and Bacteria in association with the root of Zea mays L. Microb Ecol. 2001;41:252–263. doi: 10.1007/s002480000087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dowd SE, Callaway TR, Wolcott RD, Sun Y, McKeehan T, Hagevoort RG, Edrington TS. Evaluation of the bacterial diversity in the feces of cattle using 16S rDNA bacterial tag-encoded FLX amplicon pyrosequencing (bTEFAP) BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:125. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson CR, Langner HW, Donahoe-Christiansen J, Inskeep WP, McDermott TR. Molecular analysis of microbial community structure in an arsenite-oxidizing acidic thermal spring. Environ Microbiol. 2001;3:532–542. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2001.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker GC, Smith JJ, Cowan DA. Review and re-analysis of domain-specific 16S primers. J Microbiol Meth. 2003;55:541–555. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Raybin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB, Lesniewski RA, Oakley BB, Parks DH, Robinson CJ, Sahl JW, Stres B, Thallinger GG, Van Horn DJ, Weber CF. Introducing mothur: Open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:7537–7541. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01541-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schloss PD, Gevers D, Westcott SL. Reducing the effects of PCR amplification and sequencing artifacts on 16S rRNA-based studies. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27310. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pruesse E, Quast C, Knittel K, Fuchs BM, Ludwig W, Peplies J, Glockner FO. SILVA: a comprehensive online resource for quality checked and aligned ribosomal RNA sequence data compatible with ARB. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:7188–7196. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDonald JH. Handbook of Biological Statistics. 2. Baltimore, MD: Sparky House Publishing; 2009. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information: Methods for: cultures to determine isolate activity; calculating total activity exhibited by the bacteria within the plant material.