A current debate concerning the neural control of prehension centers on the question of whether the digits in a pincer grasp are controlled individually or together. Employing a novel approach that perturbs mechanically the grasp component during a natural reach-to-grasp movement, this work is the first to test a key hypothesis: whether perturbing one of the digits during the movement affects the other. Our results support the idea that the digits are not independently controlled.

Keywords: reach to grasp, online coordination, mechanical perturbation

Abstract

Our understanding of reach-to-grasp movements has evolved from the original formulation of the movement as two semi-independent visuomotor channels to one of interdependence. Despite a number of important contributions involving perturbations of the reach or the grasp, some of the features of the movement, such as the presence or absence of coordination between the digits during the pincer grasp and the extent of spatio-temporal interdependence between the transport and the grasp, are still unclear. In this study, we physically perturbed the index finger into extension during grasping closure on a minority of trials to test whether modifying the movement of one digit would affect the movement of the opposite digit, suggestive of an overarching coordinative process. Furthermore, we tested whether disruption of the grasp results in the modification of kinematic parameters of the transport. Our results showed that a continuous perturbation to the index finger affected wrist velocity but not lateral displacement. Moreover, we found that the typical flexion of the thumb observed in nonperturbed trials was delayed until the index finger counteracted the extension force. These results suggest that physically perturbing the grasp modifies the kinematics of the transport component, indicating a two-way interdependence of the reach and the grasp. Furthermore, a perturbation to one digit affects the kinematics of the other, supporting a model of grasping in which the digits are coordinated by a higher-level process rather than being independently controlled.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY A current debate concerning the neural control of prehension centers on the question of whether the digits in a pincer grasp are controlled individually or together. Employing a novel approach that perturbs mechanically the grasp component during a natural reach-to-grasp movement, this work is the first to test a key hypothesis: whether perturbing one of the digits during the movement affects the other. Our results support the idea that the digits are not independently controlled.

from the seminal work of Jeannerod (1981, 1984), the organization of reach-to-grasp movements has been thought of as the integration of two motor programs: the reach or transport, which brings the hand close to the target object, and the grasp, which coordinates the opening, positioning, and closing of the digits. The original formulation of the model described the two components as mostly independent, with the reach responding to “extrinsic” properties of the target object such as position and orientation and the grasp to “intrinsic” properties such as size and shape. However, subsequent work involving perturbations of object size and/or position has provided clear evidence for the effects of the grasp on transport (Bootsma and van Wieringen 1992; Coats et al. 2008; van de Kamp and Zaal 2007), more specifically, that as the grasp program reorganizes to successfully attain the action goal the transport component is similarly affected to allow for that modification, suggesting a relative interdependence of the two motor components.

The use of perturbation paradigms provides us with a useful means to test the ability of the motor system to reorganize its output. Perturbations of the reach-to-grasp movement have been successfully employed to study the interdependence of the reach and grasp components but also to examine the relationship between the digits.

There are two general prevailing theories explaining how the pincer grasp is coordinated. One view suggests that the digits are individually controlled (Smeets and Brenner 1999). In brief, the respective movements of the thumb and the index finger are described as independent pointing movements where the trajectory of each digit is unaffected by the trajectory of the other. One advantage of this model is that there is no need to assume the existence of an overarching coordinative program for the opening and closing of the fingers (Smeets et al. 2009). The competing hypothesis, which has received much support (Mon-Williams and Bingham 2011; van de Kamp and Zaal 2007; Zaal and Bongers 2014), is that the hand elements are coordinated as a singular grasping apparatus. Zaal and colleagues have used an object size perturbation that modifies the location of only one of the two contact points on the object. This work has shown that modifying the trajectory of one of the two digits as the movement unfolds results in the modification of the opposite digit’s trajectory outward whether the grasping apparatus comprises a single hand (van de Kamp et al. 2009; van de Kamp and Zaal 2007) or two (Zaal and Bongers 2014).

Nonperturbation paradigms have also been employed to study this relationship. For example, Mon-Williams and Bingham (2011) used a set of difficult-to-grasp objects that nonetheless allowed for a choice of contact points for the index and the thumb. Their results showed that the end positioning of the digits was not independently selected but covaried in such a way that a clear relationship was observed between them.

These results have been taken as evidence that prehension is coordinated by a motor program that takes into account the state of both digits during the movement and suggest that a single control variable may be modulated to oversee the grasping component.

A direct approach to study this would require imposing a mechanical perturbation of one finger during a reach-to-grasp action and measuring the compensatory response of the adjacent finger and wrist. In the present study, we used a mechanical finger perturbation paradigm to test the predictions of the two views on grasping. We reasoned that if during a reach-to-grasp movement one of the digits is momentarily impeded from its intended trajectory, the kinematic outcome for the opposing digit could either remain unaffected (independent control) or exhibit compensatory effects (coordinated control). Intriguing evidence for the latter suggestion comes from an early study by Cole and Abbs (1987). This is the only study we are aware of that has used a mechanical perturbation of a finger during a static grasping task (without involving a reach component). In that study, the authors looked at the kinematic modifications on the thumb and index finger during a digit contact task under natural and perturbation conditions. The perturbation involved the application of an extension force to the thumb for half a second as the participants brought their fingertips together. Interestingly, during the thumb perturbation, the authors observed a concomitant modulation of the kinematics of the index finger in the form of joint flexion (the index moved toward the object). While the paradigm did not include a full reach-to-grasp motion, the possibility that a reorganization of the pincer movement was deployed by the modification of only one of its components suggests that a perturbation of the grasp during a reach-to-grasp movement may also result in a coordinative modification.

To test that first hypothesis, we used a mechanized exoskeleton to produce a temporary extension force on the index finger of our participants in a small percentage of grasping trials. Furthermore, we prevented visual feedback of the moving hand by conducting the experiment in the dark (the target object glowed in the dark), thereby limiting sensory feedback to somatosensory input.

A second and related issue we were interested in is how grasping interacts with the transport component. It has been known for some time that grasp and transport evolve along parallel timescales (Jeannerod 1981, 1984). More recently, following a series of studies, Rand and colleagues (2006, 2010) have proposed the existence of a control law linking hand closure to spatial (distance to object) and reach (velocity and acceleration) characteristics. Their model indicates that increased transport velocity results in longer closure distances (the distance from the object at which the hand begins to close). This suggests that if the grasp and the transport are reciprocally linked, a sudden opening of grip aperture should result in a slowing down of the wrist to allow for a proper closure distance.

As mentioned above, when object properties (e.g., the size, location, or orientation of the object) are experimentally perturbed, requiring subjects to make rapid online corrections in order to successfully grasp the object, compensatory changes in kinematics occur not only in the grasp but also in the transport component. Moreover, a similar effect is observed when the transport is perturbed mechanically. For example, Haggard and Wing (1991, 1995) implemented a mechanical perturbation of the arm during a grasping movement. Their results showed that hand aperture compensated for the effects of the perturbation. However, it remains unknown whether the reverse would hold, namely, whether a mechanical perturbation of the grasp would lead to a compensatory reorganization of the transport component.

Given that previous work has employed perturbations of the target object to study the effects on the transport and grasp components, it could be argued that the results of such paradigms may, in part, be due to the relatively slow visuomotor transformations required to recalculate the movement. Ideally, the interaction between the different components should be tested by a direct perturbation of the reach-to-grasp apparatus that bypasses the visual system.

In the present study, we used a mechanical perturbation of the index finger to force participants to modify their motor output during a reach-to-grasp action toward a constant goal. We were interested in analyzing two perturbation effects: 1) the kinematic changes of the thumb (nonperturbed digit) following the perturbation to the index finger (we hypothesized that if the fingers are independently controlled during grasp then the compensatory response should be relatively isolated to the perturbed finger, whereas if grasping is achieved in a unified manner then we may expect to see a compensatory response in the thumb) and 2) whether the transport component, suggested to be controlled independently of grasp, would also show compensatory changes as a result of the perturbed grasp.

METHODS

Subjects.

Ten right-handed subjects [2 women, 8 men; age 30.5 ± 6.6 yr (mean ± SD)] participated after providing verbal and written informed consent. Subjects were free of orthopedic or neuromuscular diseases that could interfere with the experiment. The Rutgers Institutional Review Board approved all experimental procedures.

Setup.

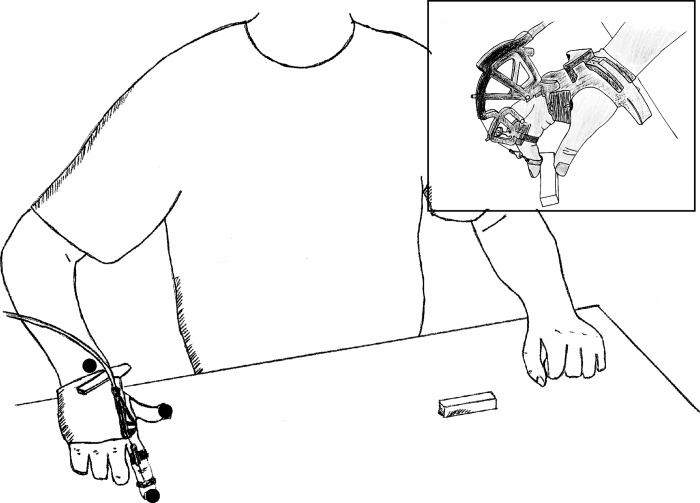

Subjects remained seated during the experiment. A lightweight force-producing hand exoskeleton (CyberGrasp, VRLOGIC) was placed over each subject’s right hand. Actuators for middle, ring, and pinkie fingers were removed to further reduce the weight of the exoskeleton. Optical motion capture sensors (100 Hz; Optotrak Certus Motion Capture System, Northern Digital) were positioned on the tip of the thumb and index finger, permitting measurement of pincer grasp aperture. A third sensor on the wrist tracked movement excursion. Subjects positioned their hand in an open grasp formation, with their thumb depressing a start button mounted to a horizontal wooden board at the level of the umbilicus and their index finger positioned over a marker ~120 mm (initial aperture) anterior to the start button (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Experimental setup. Participants maintained an initial aperture of >100 mm while their thumb pressed a switch that, when released, initiated data recording. Black circles show the approximate location of the motion tracking markers.

Procedure.

After an audible tone, subjects were instructed to grasp and vertically lift (50 mm) a rectangular block (20 × 20× 40 mm) located 250 mm to the left of the start button. Once the block was lifted, subjects placed the block down and returned to the starting position. Subjects were given 2 s to complete each trial. All trials were completed within the allotted time. The intertrial interval was randomized at 3–5 s.

The lights in the room were shut off at the time of the audible tone, preventing subjects from seeing their hands or fingers while performing the movement task. Blocking visual feedback of the hand and fingers ensured that subjects relied only on somatosensation to correct online kinematics during the perturbation trials (see below). Glow-in-the-dark paint covering the rectangular block permitted full vision of the object throughout the duration of movement. To prevent visual accommodation to darkness, the lights were immediately turned on once the object was grasped.

During a typical trial, subjects maintained the initial open-aperture finger position (120 mm). After hearing the “go” tone, they began their movement toward the target object. In perturbation (PERT) trials, a 0.5-N extension force was applied by the CyberGrasp exoskeleton at the time when grasp aperture fell below 100 mm and was sustained for the remaining duration of the trial. The CyberGrasp consists of a force control unit and actuator that receives an analog input in order to produce a steady continuous force output. The response latency of the CyberGrasp is 1–2 ms after the trigger signal from our DAQ board. In an external frame of reference, the displacement of index finger was perpendicular to the path of the index finger en route to the object, resulting in digit extension. The magnitude of the perturbation was chosen on the basis of extensive pilot testing (Schettino et al. 2015) to be comfortably tolerated by the subject pool, without requiring excessive nonspecific overflow activation across all the muscles of the hand-arm. The optimal timing of the perturbation was also extensively piloted to occur in the first 50% of the movement in order to allow the study of the early stages of prehension formation.

The data for this report are a subset of a larger experiment involving transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to study the grasping circuit (Schettino et al. 2015). In that study, TMS (75%) and NoTMS (25%) trials were randomly intermingled with NoPERT (80%, 48 trials) and PERT (20%, 12 trials) trials per block (240 trials/block, 2 total blocks). Here we only analyze the NoTMS trials to gain an understanding of the fundamental effects of physical perturbation on compensatory changes in motor coordination at the adjacent effectors in the hand. Each trial was separated by 3–5 s, according to established protocols, to prevent the effects of a TMS pulse on a given trial from influencing the subsequent trial. Because of the intertrial interval time, and the random nature of the condition order, it is highly unlikely that the NoTMS trials were inadvertently impacted by the TMS trials.

Analysis.

For the present analysis, we pooled all of the PERT and NoPERT trials, resulting in 96 NoPERT and 24 PERT trials per subject. The data were visually inspected, and trials showing errors such as early starts or sensor occlusion were marked for exclusion from the statistical analysis. At the group level, 61 trials were eliminated [49 NoPERT (5%), 12 PERT (5%)]. Data were analyzed off-line with custom-written MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA) scripts. Trial onset was defined as 50 ms before the point when aperture fell below threshold (100 mm). Trial offset was defined as when wrist velocity fell below 5% of peak velocity and/or the moment where the wrist changed to a vertical trajectory. Individual subject means were obtained for each perturbation condition. To compare across trials, data were normalized in time (temporal analysis) or longitudinal displacement (spatial analysis).

Kinematic measures.

We analyzed the following kinematic parameters: movement time (MT), defined as the interval between trial onset and offset; peak velocity (PV) and time to peak velocity (TPV); as well as peak deceleration (Pdec) and time to peak deceleration (TPdec) of the wrist. Grasp aperture was defined as the Euclidean distance between the thumb and index markers. Digit and wrist displacements were calculated in the longitudinal vs. lateral direction (horizontal plane). To compare displacement profiles, displacement was sampled at 10 points obtained at regular intervals starting from 5% to 95% along the longitudinal axis. Similarly, to compare temporal events, relative time was sampled at 10 points obtained at regular time intervals from 5% to 95% of MT.

Statistical analysis.

Kinematic differences between conditions in MT, PV, TPV, Pdec, and TPdec were compared with paired t-tests. Wrist trajectory was assessed with a two-way repeated measures (rm)ANOVA with perturbation condition (No, Yes) and displacement (5–95%) as factors. Digit lateral displacement due to the perturbation was analyzed with a three-way rmANOVA with digit (thumb, index), perturbation condition (No, Yes), and longitudinal displacement (5–95%) as factors. In the temporal domain, digit trajectory was analyzed with a two-way rmANOVA with perturbation condition (NoPERT, PERT) and time point (5–95%) as factors. In cases where the sphericity assumption was violated, significance was established with Huynh-Feldt corrections. Significant two-way interactions were followed up with Bonferroni-Holm sequential tests to determine the location of significant differences between the traces.

RESULTS

Grasp perturbation modified timing and velocity of hand transport.

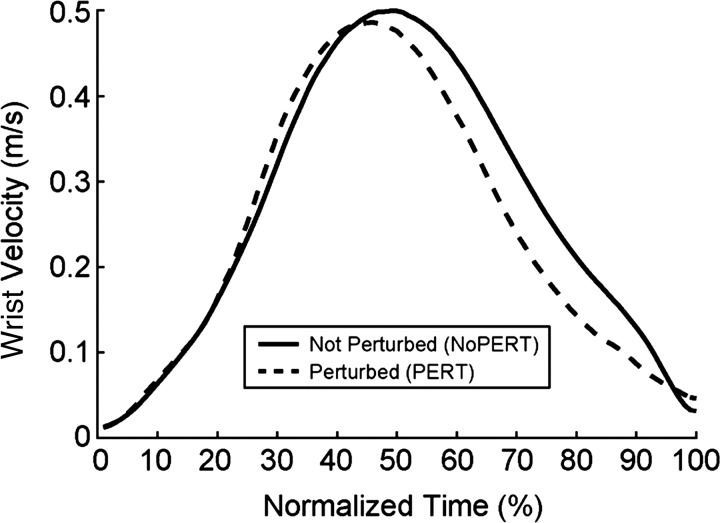

Table 1 shows the kinematic parameters of the wrist for the NoPERT and PERT conditions. The presence of the perturbation resulted in lower PV (t9 = 4.56, P = 0.001) and consequently longer MT (t9 = 8.13, P < 0.001). Figure 2 shows the velocity profiles for each condition. As can be observed, the perturbation resulted in earlier TPV (t9 = 5.28, P = 0.001), earlier TPdec (t9 = 2.56, P = 0.03), and a greater Pdec (t9 = 2.55, P = 0.03), resulting in a protracted approach to the object.

Table 1.

Kinematic parameters

| Condition | Movement Time, ms | PV, m/s | %TPV | Pdec, m/s | %TPdec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NoPERT | 595.5 (6.4) | 0.5 (0.059) | 28.8 (7.25) | −0.019 (0.003) | 55.7 (11.82) |

| PERT | 721.1 (7.1) | 0.48 (0.057) | 22.5 (7.96) | −0.02 (0.003) | 46.5 (6.38) |

Values are mean (SD) wrist kinematics. All kinematic measures exhibited significant differences between conditions. PV, peak velocity; %TPV, relative time to peak velocity; Pdec, peak deceleration; %TPdec, relative time to peak deceleration.

Fig. 2.

Wrist velocity curves in relative time for the 2 experimental conditions. The starting point for the x-axis corresponds to movement onset (see methods).

Hand trajectory remained invariant in the face of perturbation of grasp.

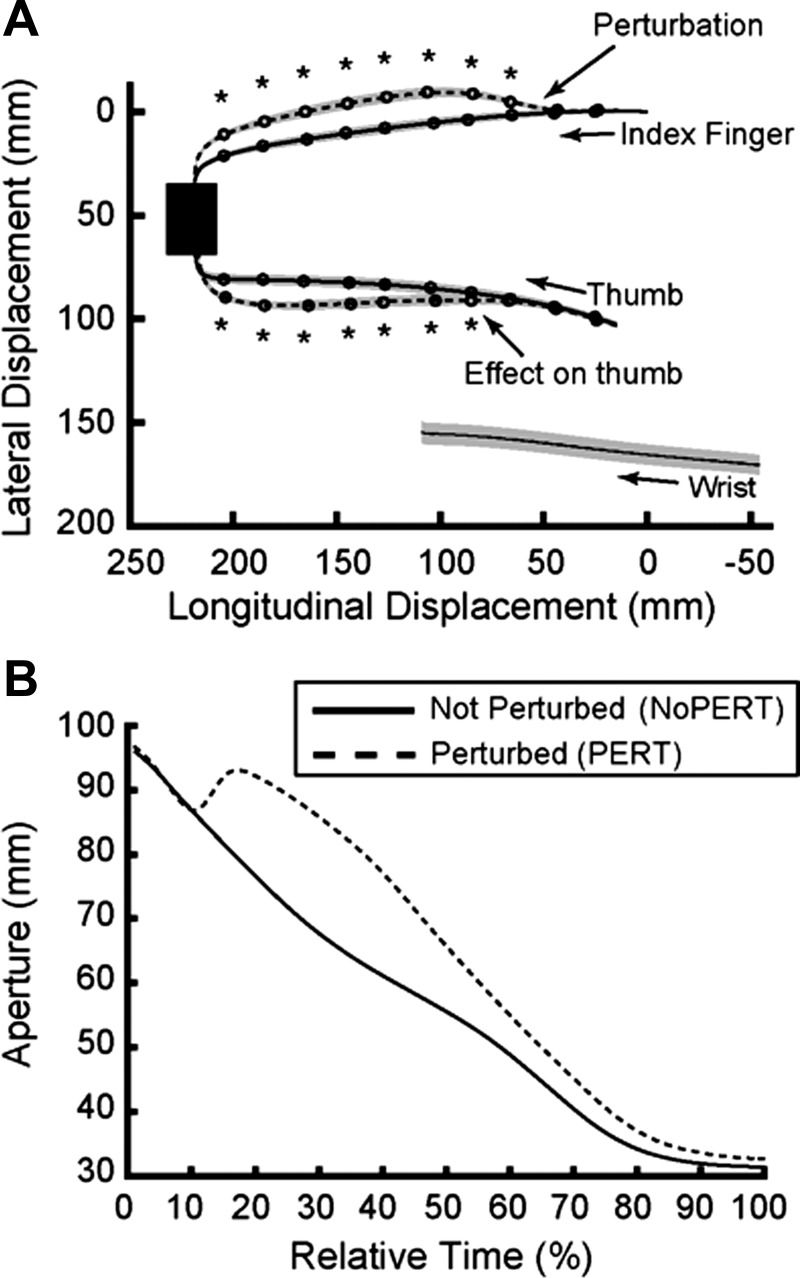

Figure 3A shows the mean displacements for the index, thumb, and wrist markers. As can be appreciated, the traces for the displacement of the wrist overlap in space, indicating that the perturbation did not cause differences in wrist lateral position during the movement. A rmANOVA conducted on the displacement of the wrist with condition (NoPERT, PERT) and lateral displacement (5–95%) as factors did not reveal significant effects of the perturbation condition, despite this being the direction of the force imposed on the finger. In other words, the spatial path of the wrist remained invariant across the perturbation conditions.

Fig. 3.

A: displacement of the index, thumb, and wrist during both NoPERT (solid lines) and PERT (dashed lines) experimental conditions. Gray areas represent ± 1 SE. B: grip aperture profiles for the NoPERT (solid line) and PERT (dashed line) conditions in normalized time (%).

Effect of perturbation on grasp aperture.

Figure 3B shows the aperture traces for the PERT and NoPERT conditions in relative time. Given that subjects began their movement with a large aperture, the movement in the NoPERT condition consisted of closing of the digits. In the PERT condition, the timing of the perturbation was ~10% of the movement across participants. At that moment (when the distance between the digits fell below 100 mm), the exoskeleton produced a continuous extension force against the index finger, which resulted in an opening of grasp aperture. The average delay for the response to the perturbation, or “perturbation reversal” (Schettino et al. 2015), was 84.6 ± 1.1 (SD) ms.

Perturbation resulted in kinematic changes in both digits.

As can be observed in Fig. 3B, the extension force on the index finger resulted in a clear deviation from the original trajectory in space (solid trace). Interestingly, the thumb also demonstrated a concurrent deviation. A rmANOVA conducted on the lateral displacements with digit (thumb, index), condition (NoPERT, PERT), and longitudinal displacement (5–95%) as factors revealed significant main effects of digit (F1,9 = 5122.3, P < 0.0001), condition (F1,9 = 5.47, P = 0.44), and displacement (F9,81 = 15.9, P = 0.001). There were also significant interactions of digit × condition (F1,9 = 427.7, P < 0.0001), digit × longitudinal displacement (F9,81 = 134.8, P < 0.0001), condition × longitudinal displacement (F9,81 = 6.6, P = 0.003), and digit × condition × longitudinal displacement (F9,81 = 141.1, P < 0.0001). Post hoc tests comparing the lateral displacement of each digit across perturbation conditions revealed significant differences between longitudinal displacement points 25–95% for the index and 35–95% for the thumb (represented with asterisks in Fig. 3A). This suggests that the effects on the thumb did not occur instantaneously with the perturbation of the index but at a notable delay.

To characterize that latency in the temporal domain, we conducted a rmANOVA with condition (NoPERT, PERT) and time point (5–95%) as factors on the relative time of the thumb trajectories. The results revealed significant main effects of perturbation (F1,9 = 87.7, P < 0.0001) and time point (F9,81 = 57.1, P < 0.0001). A significant interaction of perturbation × time point was also noted (F9,81 = 35.97, P < 0.0001). Bonferroni post hoc tests showed that time points t25–t65 exhibited significant differences, indicating that the thumb began its response at 25% of MT.

DISCUSSION

The present study focused on the coordination between the components of a reach-to-grasp movement. One of our goals was to provide evidence for one of two competing hypotheses regarding the grasp, namely, do the digits, during a reach-to-grasp movement, move independently of one another (Smeets and Brenner 1999) or are they controlled as a single unit by a higher-level process (Hoff and Arbib 1993; Saling et al. 1996)? To test this question, we produced a perturbation of the index finger during the movement by applying a constant grip-opening force. Our rationale was that if the digits work independently then the compensation for the perturbation would involve solely the index finger. Otherwise, we would observe a modification in the behavior of the thumb as well. A second objective of our experiment involved the coordination of the transport and grasp components. Given that our perturbation paradigm disrupts the grasp component, and knowing that perturbations of the transport result in modifications in the grasp (Haggard and Wing 1991, 1995), we expected the transport component to also be affected by a perturbation of the grasp.

The first main finding of our study is that a perturbation of the index finger during a reach-to-grasp movement led to a compensatory reorganized movement of the nonperturbed thumb. The most parsimonious way to describe the behavior of the thumb is that after a short delay following the perturbation of the index, it maintained its position for almost the remainder of the movement, rather than flexing toward the index as it did in the NoPERT trials. The increased aperture following the perturbation matches the results of previous studies involving object size perturbations (van de Kamp et al. 2009; van de Kamp and Zaal 2007). Nonetheless, a previous study employing a similar paradigm (Cole and Abbs 1987) used a load perturbation of the thumb during a pincer grasp task. The results, while showing a compensation by the index finger to the pull on the thumb, were in the opposite direction as those observed in our participants. That is, while our results showed an increase in grip aperture, Cole and Abbs (1987) found a movement of the index finger toward the thumb. While the reasons for this discrepancy are unclear, it is important to note that their task differed substantially from ours. During the task, their subjects’ arm was completely immobilized by a cast. Furthermore, the cast also held the thumb in place, allowing for movement only in the distal joint (the same segment that was pulled by the load). It seems reasonable to assume that these restrictions prevented a natural grasping motion that could have interfered with the patterns of sensory feedback necessary for the coordination of a reach-to-grasp movement (Gentilucci et al. 1994).

In our study, participants reached for and grasped the target object without movement restrictions other than the actual perturbation in PERT trials. While a reduction in aperture such as that observed by Cole and Abbs is difficult to explain in functional terms, a possible functional interpretation of the observed increase in aperture in our paradigm is that of an increase in safety margin to prevent bumping into the object, via a recoordinative process between the index and thumb. Furthermore, the direction of the modified trajectory suggests that the response of the thumb is unlikely to be explained by biomechanical factors. An important remaining question is whether the increased aperture reflects the widest possible distance that can be attained in the remaining grasp time (as a fixed, standardized distance) or whether it reflects a scalable amount relative to the object size or perturbation magnitude. Distinguishing between these options will require further experimentation in which object size and/or perturbation magnitude are parametrically manipulated.

Similarly, further evidence that the grip reorganization we observed has a functional role comes from the average delay of the movement of the thumb. While the actual delay varied between trials, our data suggest that the thumb response began at ~25% of relative time. Since the perturbation occurred at ~10% of relative time (Fig. 3A) and average MT in the PERT condition was 721.1 ms, the average delay can be estimated at ~108.2 ms, suggesting a supraspinal control process.

With respect to our original question, our findings do not support the view that finger coordination during pincer grasping may be organized as a multipoint reaching movement (Smeets et al. 2009; Smeets and Brenner 1999). Had this been the case, we would predict that the effects of the perturbation would be isolated to the index finger, and that the trajectory of the thumb would not differ between conditions. Rather, what we found was that the thumb significantly deviated from its natural path, leading to a significant increase in grasp aperture. This finding supports the view that pincer grasping may be organized by a unifying coordinative process.

Regarding the relationship between the transport and grip components, we observed that the spatial trajectory of hand transport, as seen in the trajectory of the wrist, remained invariant to the perturbation, indicating that the force was not strong enough to modify the movement spatially. However, the transport of the wrist did slow down, presumably to allow time for the reorganization of the pincer grasp component. This effect of a direct perturbation of the grasp component on wrist transport suggests that modifying the grasp process may result in a modification of the transport component.

Our results are in line with the Hoff-Arbib model (Hoff and Arbib 1993) in which hand state is taken into account by the transport “controller” in order to assess whether a successful grasp is feasible in the time remaining. In our study, the perturbation of the index finger impedes the process of hand closure, necessitating grasp reorganization and increasing the time required for the movement. Moreover, our results also support the notion that both the reach and the grasp interact to organize the full movement (Rand et al. 2006; Zaal et al. 1998) rather than it being the result of a hierarchical control of the transport over the grasp.

The notion of motor synergy has been used to describe the coordination of body segments suggesting the concomitant recruitment of muscles and joints (Overduin et al. 2012; Santello et al. 1998). Our results support that notion by suggesting a unitary organization for the elements of the reach-to-grasp movement in such a way that perturbing one of them results in compensatory adjustments in the others. Nonetheless, the precise neural correlates of the correction may depend on the magnitude of the deviation from the desired motor state (Fishbach et al. 2007). That is, brief, mild perturbations may be corrected through spinal control, while larger disruptions may need a modification at the level of the sensorimotor strip (S1-M1) or a modification of the motor plan at the level of parietal and premotor cortices.

We have suggested previously (Schettino et al. 2015) that our kinematic data are consistent with work in which the response to mechanical loads has been explored (Ehrsson et al. 2007; Johansson and Westling 1988). On the basis of these studies and the temporal occurrence of our responses, we have proposed that the early part of the responses, namely, the initiation of the compensatory movements, may be controlled directly by the sensorimotor strip. Nonetheless, our TMS results have shown that the modulation of the force counteracting the mechanical perturbation (and therefore modulating aperture as well) is dependent on the contralateral ventral premotor cortex (Schettino et al. 2015).

To conclude, we used a novel paradigm, involving a direct physical perturbation of a finger during a reach-to-grasping action, to test between two competing models about the control processes governing finger coordination during grasp and grasp-reach interactions. Our data support a model in which control of multiple fingers during grasping is achieved by a unitary control process of a global variable, rather than control of individual fingers as independent units. Moreover, our data are first to highlight the adaptations to the reaching component that occur in the face of mechanical perturbations of grasp.

GRANTS

This work was funded in part by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 NS-085122 (E. Tunik) and R01 HD-58301 (S. V. Adamovich).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

L.F.S., S.V.A., and E.T. analyzed data; L.F.S., S.V.A., and E.T. interpreted results of experiments; L.F.S., S.V.A., and E.T. prepared figures; L.F.S., S.V.A., and E.T. drafted manuscript; L.F.S., S.V.A., and E.T. edited and revised manuscript; L.F.S., S.V.A., and E.T. approved final version of manuscript; S.V.A. and E.T. performed experiments; E.T. conceived and designed research.

REFERENCES

- Bootsma RJ, van Wieringen PC. Spatio-temporal organization of natural prehension. Hum Mov Sci 11: 205–215, 1992. doi: 10.1016/0167-9457(92)90061-F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coats R, Bingham GP, Mon-Williams M. Calibrating grasp size and reach distance: interactions reveal integral organization of reaching-to-grasp movements. Exp Brain Res 189: 211–220, 2008. doi: 10.1007/s00221-008-1418-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole KJ, Abbs JH. Kinematic and electromyographic responses to perturbation of a rapid grasp. J Neurophysiol 57: 1498–1510, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrsson HH, Fagergren A, Ehrsson GO, Forssberg H. Holding an object: neural activity associated with fingertip force adjustments to external perturbations. J Neurophysiol 97: 1342–1352, 2007. doi: 10.1152/jn.01253.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbach A, Roy SA, Bastianen C, Miller LE, Houk JC. Deciding when and how to correct a movement: discrete submovements as a decision making process. Exp Brain Res 177: 45–63, 2007. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0652-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentilucci M, Toni I, Chieffi S, Pavesi G. The role of proprioception in the control of prehension movements: a kinematic study in a peripherally deafferented patient and in normal subjects. Exp Brain Res 99: 483–500, 1994. doi: 10.1007/BF00228985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggard P, Wing A. Coordinated responses following mechanical perturbation of the arm during prehension. Exp Brain Res 102: 483–494, 1995. doi: 10.1007/BF00230652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggard P, Wing AM. Remote responses to perturbation in human prehension. Neurosci Lett 122: 103–108, 1991. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90204-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff B, Arbib MA. Models of trajectory formation and temporal interaction of reach and grasp. J Mot Behav 25: 175–192, 1993. doi: 10.1080/00222895.1993.9942048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeannerod M. Intersegmental coordination during reaching at natural visual objects. In: Attention and Performance XI, edited by Long J, Baddeley A. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Jeannerod M. The timing of natural prehension movements. J Mot Behav 16: 235–254, 1984. doi: 10.1080/00222895.1984.10735319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson RS, Westling G. Programmed and triggered actions to rapid load changes during precision grip. Exp Brain Res 71: 72–86, 1988. doi: 10.1007/BF00247523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mon-Williams M, Bingham GP. Discovering affordances that determine the spatial structure of reach-to-grasp movements. Exp Brain Res 211: 145–160, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s00221-011-2659-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overduin SA, d’Avella A, Carmena JM, Bizzi E. Microstimulation activates a handful of muscle synergies. Neuron 76: 1071–1077, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand MK, Shimansky YP, Hossain AB, Stelmach GE. Phase dependence of transport-aperture coordination variability reveals control strategy of reach-to-grasp movements. Exp Brain Res 207: 49–63, 2010. doi: 10.1007/s00221-010-2428-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand MK, Squire LM, Stelmach GE. Effect of speed manipulation on the control of aperture closure during reach-to-grasp movements. Exp Brain Res 174: 74–85, 2006. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0423-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saling M, Mescheriakov S, Molokanova E, Stelmach GE, Berger M. Grip reorganization during wrist transport: the influence of an altered aperture. Exp Brain Res 108: 493–500, 1996. doi: 10.1007/BF00227272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santello M, Flanders M, Soechting JF. Postural hand synergies for tool use. J Neurosci 18: 10105–10115, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schettino LF, Adamovich SV, Bagce H, Yarossi M, Tunik E. Disruption of activity in the ventral premotor but not the anterior intraparietal area interferes with on-line correction to a haptic perturbation during grasping. J Neurosci 35: 2112–2117, 2015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3000-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeets JB, Brenner E. A new view on grasping. Mot Contr 3: 237–271, 1999. doi: 10.1123/mcj.3.3.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeets JB, Brenner E, Martin J. Grasping Occam’s razor. Adv Exp Med Biol 629: 499–522, 2009. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-77064-2_27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Kamp C, Bongers RM, Zaal FT. Effects of changing object size during prehension. J Mot Behav 41: 427–435, 2009. doi: 10.3200/35-08-033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Kamp C, Zaal FT. Prehension is really reaching and grasping. Exp Brain Res 182: 27–34, 2007. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-0968-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaal FT, Bongers RM. Movements of individual digits in bimanual prehension are coupled into a grasping component. PLoS One 9: e97790, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaal FT, Bootsma RJ, van Wieringen PC. Coordination in prehension. Information-based coupling of reaching and grasping. Exp Brain Res 119: 427–435, 1998. doi: 10.1007/s002210050358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]