Abstract

Adolescent sexuality research has expanded to include non-coital behaviors, but there is limited knowledge about individual factors such as cultural values associated with these sexual behaviors outside of industrialized nations. Thus, we examined associations between Latino values (familism, sexual guilt, and importance of female virginity) and three sexual behaviors (making out, oral sex, and vaginal sex), among adolescents ages 12 to 19 (53% female) in Mexico. Findings indicate that sexual guilt and importance of female virginity were consistently associated with all sexual behaviors. Some associations differed by gender and school level. For instance, sexual guilt was a better predictor of high school girls’ oral and vaginal sex. This study expands our understanding of adolescent sexuality in Mexico.

Despite greater emphasis in Mexico on interventions targeting risky sexual behaviors (Campero, Walker, Atienzo, & Gutierrez, 2011; Pick, Givaudan, & Poortinga, 2003), relatively little is known about the prevalence and predictors of non-coital sexual behaviors among adolescents in Mexico. In this study, we examined rates of making out, oral sex, and vaginal sex among youth attending middle schools and high schools in Mexico and explored whether cultural Latino values were associated with these behaviors.

Mexican nationally representative samples indicate that between 28% and 30% of youth have engaged in sexual intercourse (Gutierrez & Atiezo, 2011; Olaiz et al., 2006), with boys and older adolescent more likely to have engaged in the behavior than girls or younger adolescents (Campero et al., 2011; Gonzalez-Garza, Rojas-Martinez, Hernandez-Serrato & Olaiz-Fernandez, 2005). Less is known about non-intercourse behaviors among adolescents in Mexico. Among 10th graders, heavy petting and oral sex were infrequent with a smaller percentage of girls reporting heavy petting (8%) and oral sex (4%) than boys (24%; 7%; Campero et al., 2011).

Cultural Values and Adolescent Sexual Behavior

This study is guided by the integrative ecological model of adolescent sexuality adapted by Raffaelli, Kang, and Guarini (2012) to explain culturally diverse adolescents’ sexuality. Drawing on key model constructs, we examined culturally-relevant values (individual factors) in sexual behaviors among adolescents living in Mexico, an understudied cultural context.

Research conducted in the U.S. indicates that Latino parents may socialize adolescents to delay engaging in sexual behavior by the transmission of general (familism) and sexual (e.g., verguenza and marianismo) Latino cultural values (Villarruel, Jemmot, Jemmot & Ronis, 2007). Familism is the strong bond of nuclear and extended family members, marked by feelings of loyalty, reciprocity, and solidarity and desire to meet family expectations (Villarruel et al., 2007; Villarreal, Blozis, & Widaman, 2005). Marianismo encourages women to be pure, asexual and spiritually stronger than men, to delay sex until marriage, and defer decision making to men (Gil & Vasquez, 1996; Villarreal et al., 2005). Verguenza is defined as sexual guilt and lack of knowledge about sex (Sugar, 1995). In the current study, we assessed aspects of marianismo and verguenza relevant for adolescent sexuality (e.g., aspects of marianismo related to the importance of avoiding sexual activity until marriage). Accordingly, we refer to these values as familism, importance of female virginity, and sexual guilt.

Empirical evidence indicates that these Latino values may delay the timing of normative sexual behaviors in Latino adolescents in the U.S. (Davila, 2005; Espinosa-Hernandez, Bámaca-Colbert, Vasilenko & Mirzoeff, 2013). However, little is known about whether these values contribute to adolescent sexual behaviors in Mexico. Adolescent sexual behaviors in Mexico may be shaped by specific contexts that transmit different cultural values than those encountered by Mexican-American adolescents. For example, sexuality education in Mexican elementary schools became obligatory in 1998, and topics such as family planning and “responsible parenting” have been included in textbooks since then (Pick, Givauda, & Brown, 2000). Moreover, 40% of adults in Mexico believe that premarital sex is morally unacceptable (Poushter, 2014). Although it has been suggested that cultural values shape adolescents’ sexual behavior in Mexico (Amuchastegui, 2001; Pick et al., 2003), to our knowledge no prior quantitative research has explored these links. Thus, we examined associations between Latino values and sexual behaviors among adolescents in Mexico.

Gender and Age Differences in Values and Sexual Behavior

Research suggests that girls in Mexico are discouraged from initiating sexual activity or expressing sexual desire (Pick et al., 2003) and, thus, their transition to first sexual intercourse may be accompanied by sexual guilt. Traditional views regarding female sexuality are likely promoted by the Catholic Church, the predominant religious institution in Mexico (Amuchastegui, 2001). Perhaps due to the alignment with values like marianismo and sexual double standards that discourage sexual behavior for Latinas (Raffaelli & Iturbide, 2009), studies of Latino sexual values in the U.S. often focus on female adolescents (Davila, 2005; Espinosa-Hernandez et al., 2013). One study of Mexican-American adolescents found that values such as familism might be more relevant for girls’ than boys’ sexual expectations (Killoren, Updegraff, & Christopher, 2011), but it is unknown whether similar patterns would be found in Mexico.

Moreover, it is unclear whether the relevance of cultural values differs by gender across adolescence. As adolescents grow older, engaging in sexual behaviors becomes more normative (Gonzalez-Garza et al., 2005); therefore, older adolescents may perceive sexual activity as acceptable and be less influenced by cultural values. This may be especially true for boys (Amuchastegui, 2001; Pick et al., 2003). Therefore, we examined gender differences in two school contexts that cover the developmental span of early-middle adolescence (i.e., middle school) and late adolescence (i.e., high school). Based on prior research (e.g., Amuchastegui, 2001; Gonzalez-Garza et al., 2005; Killoren et al., 2011), we posited that associations would be strongest for middle school girls.

Present Study

We examined adolescent sexual behaviors in Puebla, Mexico, and explored whether Latino cultural values are associated with these behaviors. We had two main aims:

To examine differences in lifetime prevalence of three sexual behaviors (making out, oral sex, and vaginal sex) by gender and school level (i.e., middle and high school).

To examine a) whether the cultural values of familism, importance of female virginity, and sexual guilt were associated with sexual behavior, and b) whether gender and school grade moderated these associations. We predicted that associations between values and sexual behavior would be stronger for middle school girls than the other 3 groups (middle school boys, high school boys and girls).

Method

Participants

Participants were from a study with adolescents in Mexico (N = 1436, 52.7% female, M age = 14.5, SD = 1.43, range 12–19). Participants attended 8th, 9th (middle school; 71%), 11th and 12th grade (high school; 29%). Most (70%) lived with both their biological mother and father.

Procedure

The principal investigator contacted principals of seven middle schools (4 private and 3 public) and one high school in Puebla, one of the largest cities in Mexico. Principals chose the classrooms to participate, based on convenience (e.g., exam or class schedules). University IRB procedures were followed and a waiver of written parental consent obtained. School staff distributed forms to students to take home to parents, and separated students whose parents did not allow them to participate. Over 60% of enrolled students in each school participated, with the exception of one large middle school where fewer classes were sampled and about 30% of the students participated. Adolescents were informed of their rights as participants, and those who assented completed the survey during class time in April and May 2010. Students were assured of the confidentiality of their answers and IDs were assigned to each questionnaire. Adolescents completed the survey in about an hour and a half, and received candy for participating.

Measures

Measures were translated by committee approach (Cha, Kim, & Erlen, 2007). Bilingual research assistants and the first author translated the items as a group. Following this, two Mexican middle school students and a Mexican female school psychologist reviewed the Spanish version to ensure items were age and culturally appropriate. A pilot data collection was conducted in a small private middle school in Mexico City and a teacher suggested rewording unclear instructions. All participants completed questionnaires in Spanish.

Familism

We assessed familism (e.g., “The family should consult close relatives [uncles, aunts] concerning its important decisions”) with 6 items from the Cultural Values Familism subscale (Unger et al., 2002). Participants rated each item on a scale from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 4 (Strongly Agree). Reliability in the current study was good (α = .93). Higher scores indicate stronger familism; M = 3.08 (SD = .53).

Importance of female virginity

Adolescents completed the 3-item Female Virginity as Important scale (Deardorff, Tschann, & Flores, 2008; e.g., “Do you think it’s okay for female adolescents to have sex before marriage?”). Participants rated each item from 1 (Definitely Yes) to 4 (Definitely No). Reliability was acceptable (α = .65). Higher scores indicated higher endorsement of female virginity; M = 3.09 (SD = .53).

Sexual guilt

Adolescents responded to 2 items from the Self-acceptance scale (Deardorff et al., 2008): “Do you feel guilty about having sex?”; “Do you feel guilty about having sexual feelings?” Participants rated each item from 1 (Very much) to 5 (Not at all). Reliability in the current study was adequate (α = .69). Responses were reversed and averaged so higher scores indicating more sexual guilt; M = 2.4 (SD = 1.17).

Sexual behaviors

We assessed whether or not adolescents had engaged in four sexual behaviors with items from the Romantic and Sexual History Survey (Smetana & Gettman, 2006): making out (kissing and rubbing outside of clothes), receiving and performing oral sex, and vaginal sex. Because few adolescents engaged in one type of oral sex but not the other, we combined these into a single oral sex category for the main analyses. Adolescents marked whether they had engaged in each behavior while in each grade from 4th to 12th grade. Responses were recoded into dichotomous indicators (1 = Yes, 0 = No) of ever engaging in each behavior.

Control variables

Mother’s education was used as a proxy indicator for SES (0 = less than high school degree, 1 = high school degree). Non-intact family measured whether an adolescent lived with both parents (coded 0) or any other arrangement (coded 1).

Plan of Analysis

Preliminary analyses involved computing descriptive statistics and examining correlations among study variables. To test Aim 1, we cross-tabulated each sexual behavior by gender and school level, with Χ2 tests to identify significant differences. To test Aims 2a and 2b, we conducted six multivariate logistic regression models. The first three models (main effect) included all control variables and the three cultural values. The second three models included interactions of values with gender and school level. A full model including all predictors and two-way and three-way interactions was tested; non-significant interactions were deleted one at a time (starting with three-way interactions). To account for missing data, we used multiple imputation (Rubin, 1987) and report pooled estimates across 10 multiply imputed datasets.

Results

For descriptive purposes, correlations among study variables are displayed in Table 1. As shown in Table 2, most middle and high school students reported making out. Oral and vaginal sex were uncommon among middle school students but performed by a sizeable minority of high school students. Χ2 tests indicated that all sexual behaviors were significantly more likely for high school than middle school students, and for male than female adolescents.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Between Study Variables, by Gender

| Male M or % |

Female M or % |

1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Mother HS Degree |

52.8 | 43.4 | .05 | −.01 | −.02 | −.02 | .02 | −.04 | −.03 | −.04 | |

| 2. | Non-Intact Family |

28.3 | 32.2 | −.97* | 0.5 | .05 | .01 | .01 | .06 | −.05 | −.07 | |

| 3. | High School | 28.4 | 28.9 | .01 | .03 | −.17*** | −.20*** | −.29*** | .13** | .13** | .32*** | |

| 4. | Familism | 3.1 | 3.0 | .00 | −.09* | −.13** | .12** | .13** | −.05 | −.12** | −.12** | |

| 5. | Female Virginity |

7.8 | 8.7 | −.04 | .17*** | −.22*** | .11** | .22** | −.10* | −.25*** | −.31*** | |

| 6. | Sexual Guilt | 2.2 | 2.6 | −.06 | −.04 | −.30*** | .10* | .36*** | −.08 | −.15*** | −.23*** | |

| 7. | Making Out | 85.8 | 82.8 | −.07 | −.09* | .15*** | −.05 | −.13** | −.13** | .14** | .14** | |

| 8. | Oral Sex | 25.4 | 13.3 | .01 | −.07 | .16*** | −.11** | −.21*** | −.16*** | .15** | .62*** | |

| 9. | Vaginal Sex | 24.7 | 16.0 | .02 | −.07* | .26*** | −.08* | −.24*** | −.30** | .18** | .59** |

Note. M/% indicates either the mean (continuous variables) or % reporting (dichotomous variables). Correlations below diagonal are for female adolescents, above diagonal are for male adolescents.

p < .05,

p <.01,

p <.001.

Table 2.

Percentage of Mexican Adolescents Reporting Making Out, Oral and Vaginal Sex, Separated by Gender and School Level

| Middle School | High School | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male n = 353 |

Female n = 428 |

Male n = 155 |

Female n = 197 |

|

| Making Out | 86.1 | 78.9 | 94.8 | 90.9 |

| Oral Receive | 19.0 | 7.5 | 32.3 | 19.8 |

| Oral Perform | 17.8 | 8.9 | 29.7 | 18.3 |

| Vaginal Sex | 16.1 | 9.8 | 46.5 | 30.5 |

Results of Aim 2 analyses are summarized in Table 3. In the main effects models (Aim 2a), only one significant effect was found for familism; adolescents who placed greater emphasis on familism were less likely to engage in oral sex. Adolescents who placed more importance on female virginity and sexual guilt were less likely to have made out and engaged in oral and vaginal sex. In the full models (Aim 2b), there were no significant interactions in the model for making out. There were, however, significant interactions of values by gender and age in the models for oral and vaginal sex.

Table 3.

Logistic Regressions Showing Associations Between Latino Cultural Values and Engaging in Sexual Behaviors, With Interactions for Gender and School Level

| Making Out | Oral Sex | Vaginal Sex | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Effects | Main Effects | Final Model | Main Effects | Final Model | ||||||

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| Intercept | 1.91*** | .18 | −1.53*** | −1.43*** | .17 | −1.96*** | .17 | −1.93*** | .19 | |

| Mother High School Degree | −0.33 | .17 | −0.05 | .16 | −0.04 | .16 | −0.05 | .17 | −0.03 | .17 |

| Non-Intact Family | 0.00 | .17 | 0.21 | .15 | 0.19 | .16 | 0.25 | .17 | 0.25 | .17 |

| Female | −0.23 | .17 | −0.60*** | .15 | −0.81*** | .21 | −0.30 | .16 | −0.37 | .23 |

| High School (HS) | 0.63** | .22 | 0.41* | .15 | −.039 | .30 | 1.02*** | .16 | 1.12*** | .29 |

| Familism | −0.17 | .15 | −0.38** | .14 | −0.39** | .15 | −0.22 | .15 | −0.22 | .15 |

| Female Virginity | −0.10* | .04 | −0.24*** | .04 | −0.18** | .06 | −0.28*** | .04 | −0.27*** | .07 |

| Sexual Guilt | −0.20** | .07 | −0.27*** | .08 | −0.23 | .12 | −0.50*** | .09 | −0.46** | .14 |

| HS X Female | 0.09 | .44 | −0.39 | .41 | ||||||

| Virginity X Female | −0.21* | .10 | −0.05 | .11 | ||||||

| Guilt X Female | 0.17 | .18 | −0.07 | .21 | ||||||

| Virginity X HS | −0.21 | .12 | −0.11 | .13 | ||||||

| Guilt X HS | −0.07 | .24 | 0.34 | .24 | ||||||

| Virginity X Female X HS | 0.61** | .19 | 0.38* | .19 | ||||||

| Guilt X Female X HS | −0.23* | .40 | −1.00* | .38 | ||||||

Note. Model presented shows pooled estimates from 10 imputed datasets. Average Making Out X2 = 53.20***, Cox and Snell pseudo r2 = .04, Average Oral Main Effect X2 = 135.56***, Cox and Snell pseudo r2 = .10, Average Oral Final Model X2 = 156.36***, Cox and Snell pseudo r2 = .11, Average Vaginal Main Effect X2 = 230.65***, Cox and Snell pseudo r2 = .16, Average Vaginal Final Model X2 = 246.52***, Cox and Snell pseudo r2 = .17. Making Out final model is the same as main effects model due to lack of significant interactions.

p < .05,

p<. 01,

p < .001.

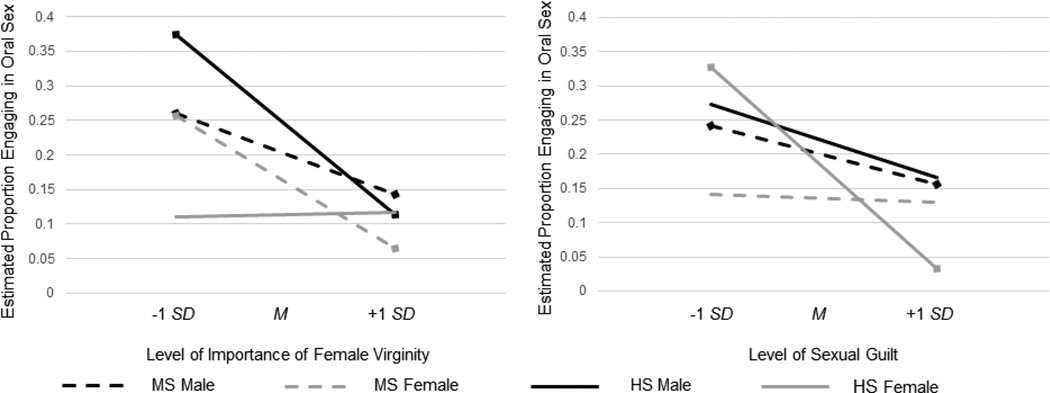

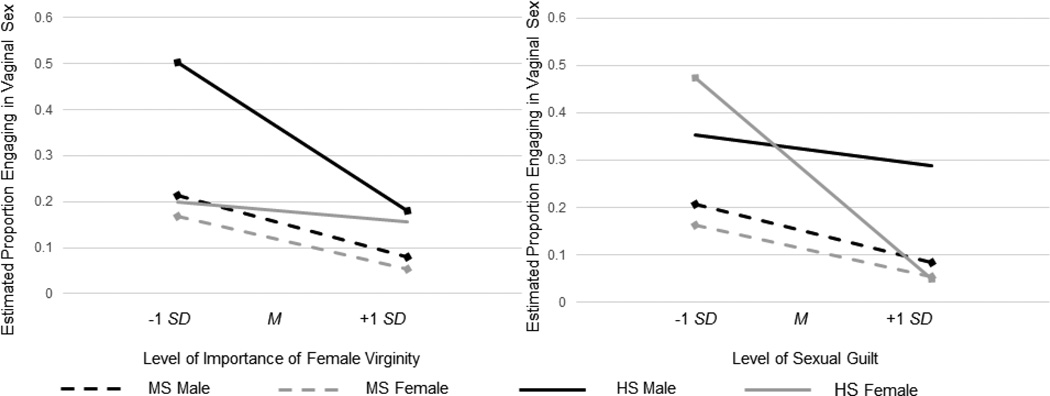

To aid in interpretation of these interactions, main effects models for oral and vaginal sex were computed separately by gender and school level, and results graphed. For boys and girls in middle school, and high school boys (but not girls), importance of female virginity was negatively associated with oral sex, whereas among high school girls and middle school boys sexual guilt was strongly negatively associated with oral sex, and this association was more pronounced for high school girls (Figure 1). Similarly, importance of female virginity was negatively associated with vaginal sex for middle school boys and girls, and high school boys (but not girls). Sexual guilt was associated with vaginal sex for all middle school students, but had a particularly pronounced association for high school girls (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Effect of importance of female virginity and sexual guilt on oral sex, calculated separately for male and female middle and high school students. MS = Middle school, HS = High school, M = Male, F = Female. Diamonds indicate statistically significant slope (p < .05).

Figure 2.

Effect of importance of female virginity and sexual guilt on vaginal sex, calculated separately for male and female middle and high school students. MS = Middle school, HS = High school, M = Male, F = Female. Diamonds indicate statistically significant slope (p < .05).

Discussion

This study expands our understanding of sexual behavior in developed nations in Latin America by assessing adolescent sexual behaviors in Mexico and exploring associations between culturally-relevant values and sexual behaviors.

Our first aim was to examine gender and age differences in different sexual behaviors. Consistent with prior research, overall rates of sexual behavior were low, particularly oral sex (Campero et al., 2011). This is in contrast to U.S. studies that report oral sex to be slightly more common than vaginal sex among youth (Halpern-Felsher et al., 2005), suggesting that oral sex may not be viewed as normative in Mexico. Consistent with previous Mexican studies, younger adolescents and girls were less likely to engage in all behaviors than older adolescents and boys. Gender differences in sexual behavior are consistent with the sexual double standard that prevails in Mexican society (Pick et al., 2003). They may, however, also reflect reporting biases; in U. S. studies, adolescent girls are more likely than boys to deny sexual involvement (Petersen & Hyde, 2011).

Our second aim had two parts. First, we examined associations between three cultural values and sexual behaviors. As expected, adolescents who endorsed values relating to the importance of female virginity and sexual guilt had a lower likelihood of engaging in all sexual behaviors. On the other hand, familism was only associated with oral sex. Oral sex may be considered a taboo among Latinos (Lindberg, Jones & Santelli, 2008), and thus adolescents who have strong family bonds may be reluctant to risk family disapproval or disappointment by engaging in oral sex. Future research should explore the mechanisms linking these variables.

Second, we examined the moderating role of gender and school level (to tap into age differences) on associations between cultural values and sexual behavior. Based on prior research (Killoren et al., 2011), we posited that associations would be strongest for middle school girls. However, we found differences by gender and school level that were not predicted. Boys and girls in middle school and high school boys who considered female virginity important were less likely to have engaged in oral and vaginal sex, compared to adolescents who consider virginity less important. In contrast, among high school girls, sexual guilt was a strong predictor of sexual behavior. U.S. studies indicate that the effect of religion on sexual behavior is stronger among girls than boys (Rostosky, Wilcox, Comer Wright, & Randall, 2004), and qualitative studies in Mexico suggest that feelings of sexual guilt among women are rooted in Catholic religion (Amuchastegui, 2001). These findings raise the possibility that sexual behavior may be more influenced by external cultural standards for boys and younger girls (middle school), whereas older girls may be influenced by internalized feelings of guilt.

The study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design and sample limit conclusions that can be drawn. Although we posited that values affect sexual behaviors, it is possible that sexual behaviors affect values (e.g., once individuals engage in sex they feel less guilty about their own sexuality). In addition, because this is a convenience sample, findings cannot be generalized to all Mexican adolescents. Second, although the sample size was large and effect sizes were robust, we examined a large number of variables and interactions, raising the possibility of Type I error. Finally, although marianismo and verguenza are multidimensional constructs (Villarreal et al., 2005), we only assessed the sexual aspects. We also did not examine values related to masculinity, such as machismo (male sexual dominance) and caballerismo (respectful manners and chivalry), which may be more relevant for Mexican boys’ sexual socialization (Arciniega, Anderson, Tovar-Blank, & Tracey, 2008).

In conclusion, our findings suggest that Latino cultural values are associated with sexual behavior in adolescents residing in Mexico. Future research that builds on this work and addresses study limitations can contribute to expanding understanding of the role of cultural values in Mexican adolescents’ sexual behaviors.

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2012 Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research on Adolescence at Vancouver, B.C. This research was supported by grant P50 DA01007 from the National Institute of Drug Abuse to Sara Vasilenko. We gratefully acknowledge Jackie Darazsdi, Julia Daugherty, Katie Hutchins, Laura Keaton, Rachel Lange, Frankie Machado, Anna Nunn for their help with data collection and data entry. We also want to thank Mrs. Zuilma Hernandez Montes De Oca, Mrs. Graciela Hernandez Coronel and all the wonderful teachers and principals who made data collection possible.

Contributor Information

Graciela Espinosa-Hernández, Psychology Department at University of North Carolina, Wilmington. UNCW, 601 South College Road, Wilmington, NC 28403, (910) 962-4057 hernandezm@uncw.edu.

Sara A. Vasilenko, Methodology Center at the Pennsylvania State University. The Methodology Center, The Pennsylvania State University, 400 Calder Square II, State College, PA 16801, (814) 867-4511 svasilenko@psu.edu.

Mayra Y. Bámaca-Colbert, Human Development and Family Studies Department at the Pennsylvania State University. 311A Health & Human Development East, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park PA 16802, (814) 867-2812 myb12@psu.edu.

References

- Arciniega GM, Anderson TC, Tovar-Blank Z, Tracey TJG. Toward a fuller conception of machismo: Development of a traditional machismo and caballerismo scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2008;55:19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Amuchastegui A. Virginidad e iniciación sexual, experiencias y sinificados [Virginity and sexual initiation, experiences and meanings] Mexico City, Mexico: Edamex; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cha ES, Kim KH, Erlen JA. Translation of scales in cross-cultural research: Issues and techniques. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007;58:386–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campero L, Walker D, Atienzo EE, Gutierrez JP. A quasi-experimental evaluation of parents as sexual health educators resulting in delayed sexual initiation and increased access to condoms. Journal of Adolescence. 2011;34:215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila YR. The social construction and conceptualization of sexual health among Mexican American women. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice. 2005;19:357–368. doi: 10.1891/rtnp.2005.19.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff J, Tschann J, Flores E. Sexual values among Latino youth: measurement development using a culturally based approach. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2008;14:138–146. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.2.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa-Hernandez G, Bamaca-Colbert MY, Vasilenko SA, Mirzoeff CA. Timing of sexual behaviors among female adolescents of Mexican-origin: The role of cultural variables. Child Studies in Diverse Contexts. 2013;3:121–135. [Google Scholar]

- Gil RM, Vazquez CI. The Maria paradox: How Latinas can merge old world traditions with new world self-esteem. New York, NY: Berkley; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Garza C, Rojas-Martinez R, Hernandez-Serrato MI, Olaiz-Fernandez G. Profile of sexual behavior in 12- to 19-year-old Mexican adolescents. Results of ENSA 2000. Salud Publica Mexico. 2005;47:209–218. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342005000300004. http://www.scielosp.org/scielo.php?pid=0036-3634&script=sci_serial. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez JP, Atiezo EE. Socioeconomic status, urbanicity and risk behavior in Mexican youth: An analysis of three cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:900–910. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern-Felsher BL, Cornell JL, Kropp RY, Tschann JM. Oral versus vaginal sex among adolescents: Perceptions, attitudes, and behavior. Pediatrics. 2005;115:845–851. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killoren SE, Updegraff KA, Christopher FS. Family and cultural correlates of Mexican-origin youth’s sexual intentions. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40:707–718. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9587-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg LD, Jones R, Santelli JS. Noncoital sexual activities among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;43:231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olaíz G, Rivera-Dommarco J, Shamah-Levy T, Rojas R, Villalpando-Hernández S, Hernández-Avila M, Sepúlveda-Amor J, et al. Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición 2006 [National Survey of Health and Nutrition 2006] Cuernavaca, Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública; 2006. Retrieved from: http://www.facmed.unam.mx/deptos/salud/censenanza/spi/unidad2/ensanut2006.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen JL, Hyde JS. Gender differences in sexual attitudes and behaviors: A review of meta-analytic results and large datasets. Journal of Sex Research. 2011;48:149–165. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.551851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pick S, Givaudan M, Brown J. Quietly working for school-based sexuality education in Mexico: Strategies for advocacy. Reproductive Health Matters. 2000;8:92–102. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(00)90191-5. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3775275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pick S, Givaudan M, Poortinga YH. Sexuality and life skills education: A multistrategy intervention in Mexico. American Psychologist. 2003;3:230–234. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.3.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poushter J. Pew Research Center. What is morally acceptable? It depends on where in the world you live. 2014 http://www.pewglobal.org/2014/04/15/global-morality/ [Google Scholar]

- Raffaelli M, Iturbide MI. Sexuality and sexual risk-taking behaviors among Latino adolescents and young adults. In: Villaruel F, Carlo G, Azmitia M, Grau J, Cabrera N, Chahin J, editors. Handbook of U.S. Latino Psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2009. pp. 399–414. [Google Scholar]

- Raffaelli M, Kang H, Guarini T. Exploring the immigrant paradox in adolescent sexuality: An ecological perspective. In: Garcia Coll C, Marks A, editors. Is becoming an American a developmental risk? Washington, DC: APA; 2012. pp. 109–134. [Google Scholar]

- Rostosky S, Wilcox BL, Comer Wright M, Randall BA. The impact of religiosity on adolescent sexual behavior: A review of the evidence. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2004;19:677–697. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York, NY: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Gettman DC. Autonomy and relatedness with parents and romantic development in African American adolescents. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:1347–1351. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.6.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugar M. Facets of adolescent sexuality. In: Mahron RC, Feinstein SC, et al., editors. Adolescent psychiatry: Developmental and clinical studies. Hillsdale, NJ: Analytic Press, Inc.; 1995. pp. 139–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman DL, McClelland SI. Normative sexuality development in adolescence: A decade in review, 2000–2009. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21:242–255. [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Teran L, Huang T, Hoffman BR, Palmer P. Cultural values and substance use in a multiethnic sample of California adolescents. Addiction Research and Theory. 2002;10:257–279. [Google Scholar]

- Villarreal R, Blozis SA, Widaman KF. Factorial invariance of a pan-Hispanic familism scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2005;27:409–425. [Google Scholar]

- Villarruel AM, Jemmott JB, III, Jemmott LS, Ronis DL. Predicting condom use among sexually experienced Latino adolescents. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2007;29:724–738. doi: 10.1177/0193945907303102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]