Abstract

Background

School‐based sexual and reproductive health programmes are widely accepted as an approach to reducing high‐risk sexual behaviour among adolescents. Many studies and systematic reviews have concentrated on measuring effects on knowledge or self‐reported behaviour rather than biological outcomes, such as pregnancy or prevalence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of school‐based sexual and reproductive health programmes on sexually transmitted infections (such as HIV, herpes simplex virus, and syphilis), and pregnancy among adolescents.

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE, Embase, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) for published peer‐reviewed journal articles; and ClinicalTrials.gov and the World Health Organization's (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform for prospective trials; AIDS Educaton and Global Information System (AEGIS) and National Library of Medicine (NLM) gateway for conference presentations; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), UNAIDS, the WHO and the National Health Service (NHS) centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) websites from 1990 to 7 April 2016. We handsearched the reference lists of all relevant papers.

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), both individually randomized and cluster‐randomized, that evaluated school‐based programmes aimed at improving the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trials for inclusion, evaluated risk of bias, and extracted data. When appropriate, we obtained summary measures of treatment effect through a random‐effects meta‐analysis and we reported them using risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We assessed the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach.

Main results

We included eight cluster‐RCTs that enrolled 55,157 participants. Five trials were conducted in sub‐Saharan Africa (Malawi, South Africa, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, and Kenya), one in Latin America (Chile), and two in Europe (England and Scotland).

Sexual and reproductive health educational programmes

Six trials evaluated school‐based educational interventions.

In these trials, the educational programmes evaluated had no demonstrable effect on the prevalence of HIV (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.32, three trials; 14,163 participants; low certainty evidence), or other STIs (herpes simplex virus prevalence: RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.15; three trials, 17,445 participants; moderate certainty evidence; syphilis prevalence: RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.39; one trial, 6977 participants; low certainty evidence). There was also no apparent effect on the number of young women who were pregnant at the end of the trial (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.16; three trials, 8280 participants; moderate certainty evidence).

Material or monetary incentive‐based programmes to promote school attendance

Two trials evaluated incentive‐based programmes to promote school attendance.

In these two trials, the incentives used had no demonstrable effect on HIV prevalence (RR 1.23, 95% CI 0.51 to 2.96; two trials, 3805 participants; low certainty evidence). Compared to controls, the prevalence of herpes simplex virus infection was lower in young women receiving a monthly cash incentive to stay in school (RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.85), but not in young people given free school uniforms (Data not pooled, two trials, 7229 participants; very low certainty evidence). One trial evaluated the effects on syphilis and the prevalence was too low to detect or exclude effects confidently (RR 0.41, 95% CI 0.05 to 3.27; one trial, 1291 participants; very low certainty evidence). However, the number of young women who were pregnant at the end of the trial was lower among those who received incentives (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.58 to 0.99; two trials, 4200 participants; low certainty evidence).

Combined educational and incentive‐based programmes

The single trial that evaluated free school uniforms also included a trial arm in which participants received both uniforms and a programme of sexual and reproductive education. In this trial arm herpes simplex virus infection was reduced (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.99; one trial, 5899 participants; low certainty evidence), predominantly in young women, but no effect was detected for HIV or pregnancy (low certainty evidence).

Authors' conclusions

There is a continued need to provide health services to adolescents that include contraceptive choices and condoms and that involve them in the design of services. Schools may be a good place in which to provide these services. There is little evidence that educational curriculum‐based programmes alone are effective in improving sexual and reproductive health outcomes for adolescents. Incentive‐based interventions that focus on keeping young people in secondary school may reduce adolescent pregnancy but further trials are needed to confirm this.

15 April 2019

Update pending

Studies awaiting assessment

The CIDG is currently examining a new search conducted in April 2019 for potentially relevant studies. These studies have not yet been incorporated into this Cochrane Review. All eligible published studies found in the last search (7 Apr, 2016) were included and five ongoing studies were identified (see 'Characteristics of ongoing studies' section).

Plain language summary

School‐based interventions for preventing HIV, sexually transmitted infections, and pregnancy in adolescents

Cochrane researchers conducted a review of the effects of school‐based interventions for reducing HIV, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and pregnancy in adolescents. After searching for relevant trials up to 7 April 2016, they included eight trials that had enrolled 55,157 adolescents.

Why is this important and how might school‐based programmes work?

Sexually active adolescents, particularly young women, are at high risk in many countries of contracting HIV and other STIs. Early unintended pregnancy can also have a detrimental impact on young people's lives.

The school environment plays an important role in the development of children and young people, and curriculum‐based sexuality education programmes have become popular in many regions of the world. While there is some evidence that these programmes improve knowledge and reduce self‐reported risk taking, this review evaluated whether they have any impact on the number of young people that contracted STIs or on the number of adolescent pregnancies.

What the research says

Sexual and reproductive health education programmes

As they are currently configured, educational programmes alone probably have no effect on the number of young people infected with HIV during adolescence (low certainty evidence). They also probably have no effect on the number of young people infected with other STIs (herpes simplex virus: moderate certainty evidence; syphilis: low certainty evidence), or the number of adolescent pregnancies (moderate certainty evidence).

Material or monetary incentive‐based programmes to promote school attendance

Giving monthly cash, or free school uniforms, to encourage students to stay in school may have no effect on the number of young people infected with HIV during adolescence (low certainty evidence). We do not currently know whether monthly cash or free school uniforms will reduce the number of young people infected with other STIs (very low certainty evidence). However, incentives to promote school attendance may reduce the number of adolescent pregnancies (low certainty evidence).

Combined educational and incentive‐based programmes

Based on a single included trial, giving an incentive such as a free school uniform combined with a programme of sexual and reproductive health education may reduce STIs (herpes simplex virus; low certainty evidence) in young women, but no effect was detected for HIV or pregnancy (low certainty evidence).

Authors' conclusions

There is currently little evidence that educational programmes alone are effective at reducing STIs or adolescent pregnancy. Incentive‐based interventions that focus on keeping young people, especially girls, in secondary school may reduce adolescent pregnancy but further high quality trials are needed to confirm this.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Adolescents have been recognized as having an important place in the post‐2015 development agenda (United Nations 2015); indeed three of the United Nation's sustainable development goals (SDGs) specifically target adolescent sexual and reproductive health, and access to appropriate health services as a human right. However, adolescents, particularly those under 16 years of age, constitute a high‐risk group who are less likely to use or have access to condoms or contraceptives (Harrison 2005; Mathews 2009; Pettifor 2005; UNAIDS 2012).

Incident HIV infections amongst young people aged 15 to 24 years account for almost half of new infections (UNAIDS 2012). These have increased since 2000, with adolescents within the African region having 90% of the world's HIV‐related adolescent deaths (World Health Organization 2014). Despite a downward trend in adolescent pregnancy worldwide (World Bank 2016), most pregnancies in girls under the age of 18 are unwanted and many are terminated. Restrictive abortion laws and lack of services can result in high levels of maternal mortality (Grimes 2006). If the pregnancy is continued and unwanted, it is associated with adverse outcomes for both the mother's and infant's health (Pallitto 2005). A meta‐analysis that examined risk factors for pregnancy for girls aged between 13 and 19 years, found that sociodemographic indicators, family disruption, and leaving school early were the most consistently associated factors (Imamura 2007).

The effect of intimate partner violence on young women’s ability to control their sexual and reproductive health has also been highlighted as an important issue (Garcia‐Moreno 2013). Poor health‐related outcomes can result from lack of autonomy and difficulty in accessing services. Pregnancy coercion and birth control sabotage has been linked to unintended pregnancy (Miller 2010; Thiel de Bocanegra 2010), and limitations on condom use (Katz 2015), which increases the risk and incidence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including HIV (Dhairyawan 2013). It is also associated with poor perinatal and maternal health with increased risk of low birth weight and preterm birth (Shah 2010).

Programmes that promote sexual abstinence and delay of sexual initiation in adolescence have been unsuccessful in reducing self‐reported pregnancy and STIs (Underhill 2008; Oringanje 2016).

Description of the intervention

The school environment plays a pivotal role in the socialization and development of children and young people and has been considered to be an appropriate setting for interventions to promote adolescent sexual and reproductive health (Dick 2006; Mason‐Jones 2012; UNAIDS 1997).

Schools bring together large numbers of young people within an established infrastructure, and can provide systems into which interventions can be incorporated. As many young people spend a substantial amount of time in school, it is also an arena for peer connections and the development of relationships that influence individual and group behaviour within the school, and beyond into local communities; although it is important to recognize that schools are not always supportive or safe social environments for young people (Abrahams 2006; Kaplan 2007; Plummer 2007). It is known that dropping out of school can result in adverse health outcomes for young people (Freudenberg 2007).

Schools have been the setting for many sexual and reproductive health programmes that have been regarded as being successful (Kirby 2006), and curriculum‐based sexuality education programmes have become popular in many regions of the world. Most of these programmes have been based on the theory of social learning (Bandura 1977), the health belief model (Rosenstock 1988), the theory of reasoned action (Fishbein 2010) ‐ or adaptations of these theories ‐ and aim to change attitudes, intentions, behaviours, and social norms through improved knowledge and understanding of the risks of early sexual initiation, and the importance of contraceptive and/or condom use. Many studies have also incorporated the 17 characteristics of programmes that are considered previously to have been successful (Kirby 2009).

Thus, a range of educational interventions has been developed to promote sexual and reproductive health among adolescents, which aims to reduce the incidence of HIV, STIs, and early unwanted pregnancies. Many of these programmes encourage abstinence from sexual activity, the postponement of sexual debut until later years, or encourage secondary delay (that is, those who have their sexual debut delaying further sexual activity). They also encourage increase in condom use among those adolescents who are sexually active. Interventions include programmes delivered by teachers or peer educators that may be supplemented by condom distribution programmes, and others that include targeted health service provision and include drama, role play, and other engagement activities.

Other evidence suggests that simply staying on at school can have positive effects on sexual and reproductive health outcomes, and that encouraging school attendance helps girls in particular to avoid early sexual activity and pregnancy (Black 2008; Monstad 2008).

How the intervention might work

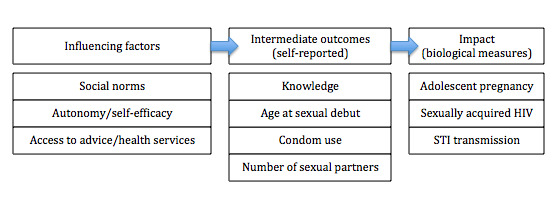

Many sexual and reproductive health education programmes are based on behavioural science theories (Glanz 2010), and aim to improve knowledge, change attitudes, intentions, behaviours, and social norms around sexual and reproductive health. There have been a large number of systematic reviews that evaluated the effectiveness of these programmes (Chin 2012; Dick 2006; DiClemente 2008; Flisher 2008; Gallant 2004; Harrison 2010; Johnson 2003; Johnson, 2011; Kim 2008; Kirby 2007; Lazarus 2010; Magnussen 2004; Medley 2009; Michielsen 2010; Paul 2008; Shepherd 2010; Yankah 2008), including reviews that have focused solely on school‐based interventions (Bennet 2005; Fonner 2014; Kirby 2006; Lopez 2016; Paul 2008), and a review of reviews (Mavedzenge 2013). Many of these reviews have suggested that school‐ and community‐based prevention programmes for adolescents have been effective in delaying self‐reported sexual activity, HIV‐related preventative behaviours, adolescent pregnancy, and STIs (Chin 2012; Fonner 2014; Johnson 2003; Johnson, 2011; Kirby 2009; Laud 2016), although others have reported less, or mixed, success (Bennet 2005; DiCenso 2002; Lopez 2016Oringanje 2016). The logic model for how these programmes might be thought to influence sexual and reproductive health outcomes can be seen in Figure 1.

1.

Logic model showing potential causal chain from influencing factors to impact.

As school dropout has negative effects on health outcomes for young people (Freudenberg 2007), researchers have become interested in using cash or other types of transfers (such as free school uniforms or vouchers) as incentives for adolescents to remain at school (Baird 2009; Baird 2010). Conditional and unconditional cash or other transfer programmes have been introduced to take into account the substantial financial barriers to remaining at school or to accessing health services (Pettifor 2012), especially where these are not freely provided on a universal basis. These programmes view staying at school ‐ especially for girls ‐ as a ‘social vaccine’, based on evidence that the longer adolescents stay in education the less likely they are to engage in high risk sexual behaviour, such as transactional sex, or because pregnancy or STI/HIV risks would interrupt their longer‐term aspirations and career plans.

Why it is important to do this review

Most evaluations of school‐ and community‐based programmes, or indeed of any interventions to improve the sexual and reproductive health of young people, have used self‐reported sexual behaviours as their main outcomes. However, self‐report measures have been found to be prone to bias (Langhaug 2011; Plummer 2004), and, as such, may well be an unreliable surrogate measure for effects such as sexually acquired infections and pregnancy (Brown 2015). Therefore, this review focuses on the effect of such interventions on biological outcome measures. Incidence of HIV or other STIs, or pregnancy are the most convincing indicators of the effectiveness of preventative interventions. This systematic review provides a unique contribution to the field because it only included studies if biological outcomes, such as HIV, STIs, or pregnancy, had been measured objectively. There are also varying interpretations of the strength of the evidence regarding school‐based HIV, STIs, and pregnancy prevention programmes for adolescents. This systematic review also provides more detail about the current strength of the evidence by using the GRADE assessment tool.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of school‐based sexual and reproductive health programmes on sexually transmitted infections (such as HIV, herpes simplex virus, and syphilis), and pregnancy among adolescents.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (both individually randomized and cluster‐randomized).

Types of participants

Adolescents (defined as 10 to 19 year olds) attending primary, middle, or high (secondary) school at the time of the intervention.

In countries where children start school at a later age, or where school populations sometimes include young people over the age of 20 years, we included these studies if most of the participants (over 50%) were adolescents.

Types of interventions

We included any intervention that aimed to reduce the risk of HIV or other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) or pregnancy among adolescents, and was primarily conducted in schools or linked to schools or school attendance, with or without a community component. Some were curriculum‐based educational interventions primarily delivered by adults (teachers, or other adults) or peers (peer educators), or included additional features to change the school or community environment (for example, by changing school policies or improving health services). Other interventions focused on encouraging adolescents to stay at school by providing incentives (cash or other material transfers).

Types of outcome measures

Clinical/biological outcomes:

HIV prevalence;

STI prevalence;

Pregnancy prevalence.

Behavioural self‐reported outcomes:

use of male condoms at first sex;

use of male condoms at most recent (last) sex;

incidence of sexual initiation (sexual debut).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We developed the search strategy with the assistance of the HIV/AIDS Review Group Information Specialist and developed a comprehensive search strategy in an attempt to identify all relevant studies regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press, and in progress). We searched the following bibliographic databases for the years 1990 to 7 April 2016 using the search terms presented in the Appendices: MEDLINE (Appendix 1), Embase (Appendix 2), CENTRAL (the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) (Appendix 3), the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch; Appendix 4), and ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov). We also searched the following conference databases: AIDS Education Global Information System (AEGIS) (www.aegis.com), and NLM GATEWAY (gateway.nlm.nih.gov/gw).

Searching other resources

We also searched libraries of relevant organizations and international agencies: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), UNAIDS, the WHO, and the National Health Service (NHS) Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD). We handsearched the reference lists of all relevant papers, including systematic reviews and reviews of reviews. We contacted researchers, research institutions, relevant government departments, and organizations that were known to conduct school‐based HIV intervention research or were known to us to identify further published and unpublished studies. Where we were unable to obtain sufficient data from the published articles, we contacted the study authors to request further information about ongoing trials, raw data, and unpublished work.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

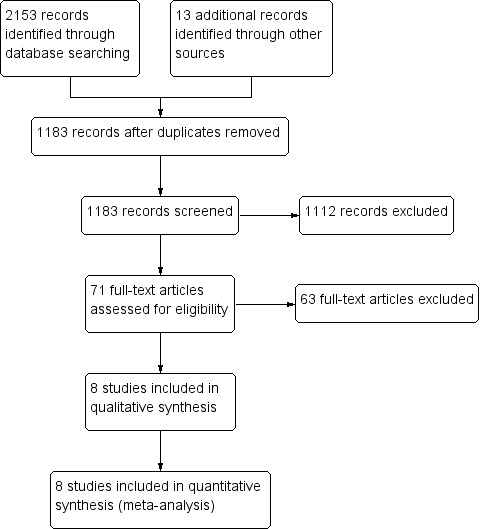

Two review authors (AMJ and either DS, CM, AH, or AK) independently reviewed all titles and abstracts identified in the search for relevant trials for the review. We obtained full‐text articles for all studies that both review authors recorded as potentially relevant for the review. If the two review authors did not agree initially, we obtained the full‐text article and consulted a third review author to make the decision. We listed all full‐text articles that we excluded and their reasons for exclusion in a 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table. Also, we constructed a PRISMA diagram to illustrate the study selection process (Figure 2).

2.

Study flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (AMJ and either DS, CM, AH, or AK) independently extracted data on study design (location, context, theoretical framework, dates, duration of follow‐up), participants (age, gender, language, ethnicity), interventions (type and complexity of the intervention and all the component parts, length of training of teachers or facilitators, content and duration of the intervention, intensity of the intervention), and methodological quality (method of randomization, attrition, sample size, adjustments for assignment bias, appropriateness of analysis for cluster RCTs, potential confounders, and protection against contamination), using a standardized data extraction form designed specifically for the purpose.

For the meta‐analysis of the trials the effect measure we used for inference was the relative risk of the outcome. Some of the included trials reported this measure, but other trials reported odds ratios. To convert the information from these studies into a relative risk framework, we used frequencies of observed outcomes and odds ratio effect estimates and corresponding confidence limits to estimate the design effect (DE) and intraclass correlation (ICC) for each study overall. We did this by estimating the variance of the odds ratio under the assumption of independence from the raw frequencies, extracting the variance of the odds ratio from the confidence limits adjusted for clustering, and then calculating the design effect as the ratio of the variance (clustered) over the variance (independence). We followed the guidelines from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions to reduce the size of each trial to its 'effective sample size' (Rao 1992). We then solved the corresponding ICC from the standard design effect equation (DE = 1+(m‐1)*ICC, where m is the average cluster size). We used this information to adjust the standard error of the relative risk estimate for clustering (McKenzie 2014). If the ICC or design effect was not reported, we assumed the ICC to be 0.1, as in a previous review of school‐based studies (Walsh 2015).

For Stephenson 2008 GBR, we estimated the DE from the unweighted effect measures and confidence intervals (CIs) reported. We then applied this estimated DE to the weighted estimates and CIs reported.

We managed trials with multiple publications as one study. One trial incorporated three interventions that were meta‐analysed separately (Duflo 2015 KEN). We entered eligible trials into Review Manager (RevMan) 5.3 (Review Manager 5.3). Where methods, data or analyses were unclear, we contacted the trial authors for clarification. We resolved any discrepancies and disagreements by discussion amongst the review author team. There were a few disagreements, generally as a result of differing interpretations of the texts or tables, and we resolved these by going back to the original or supporting papers, or back to the review authors to resolve.

We assessed the quality of evidence using the GRADE approach (GRADEpro 2014).

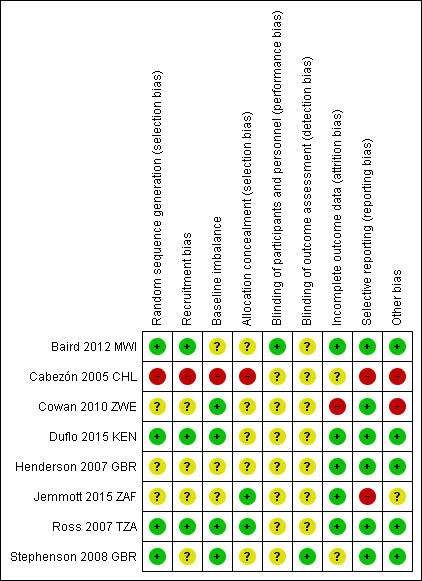

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We independently examined the components of each included trial for risk of bias using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' assessment tool (Higgins 2011), and incorporated those items specifically related to cluster‐RCTs. This included information on random sequence generation, recruitment bias, baseline imbalance, allocation concealment, blinding (of participants, personnel, and the outcome assessors), incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other sources of bias. We assessed the methodological components of the trials and classified them as being at either high, low, or unclear risk of bias. Again, we resolved any differences of opinion by discussion.

Measures of treatment effect

We reported all outcomes using risk ratios (RR) with 95% CIs.

Dealing with missing data

We aimed to conduct a complete‐case analysis so that we included all individuals with a recorded outcome in the analysis. If missing information was a problem, or we needed more details on reported measures, we sought further clarification from study investigators. All included trials reported at least one of the main outcome measures. However, one trial did not include the data in the final published paper and we were unable to get this data for inclusion in the review despite contacting the trial authors (Jemmott 2015 ZAF).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity between trials by inspecting the forest plots to detect overlapping CIs and by calculating the I² statistic using RevMan 5.3 (Higgins 2003). We also conducted a Chi2 test for heterogeneity at the P=0.1 level.

Assessment of reporting biases

When we reported the results of the included trials, we used the intention‐to‐treat results for the meta‐analysis. We did not construct funnel plots to look for evidence of publication bias because there were too few trials included in each analysis.

Data synthesis

Two review authors, AMJ and CL, analysed data using RevMan 5.3 (Review Manager 5.3). Given that the included trials used a variety of interventions, where it was appropriate to combine trials in a meta‐analysis we used a random‐effects model, since this is a conservative approach based on fewer assumptions than the fixed‐effect approach. We stratified the primary analysis by gender and performed a subgroup analysis by type of intervention (primarily curriculum‐based versus incentive‐based, and incentive‐based plus curriculum) where this was possible. Where trials reported incidence rates (for example, Ross 2007 TZA), we estimated the total number of infections reported and added this to the baseline infections to get an overall prevalence of infections at the endpoint of the trial. Where trials reported the inverse outcome we inverted the reported numbers. For Henderson 2007 GBR we estimated the number of respondents who were evaluated for using a condom at last sex and we then used this as the number of sexually active participants in the trial.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted subgroup analyses for young women and young men separately. We also conducted subgroup analyses for type of intervention (for example, education‐based interventions and incentives to stay at school).

'Summary of findings' tables

We used a 'Summary of findings' table to interpret the results and to provide key information about the certainty of evidence for included trials in the comparison, magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and included available data on the main outcomes. We used the GRADE profiler, GRADEpro 2014, to import data from RevMan 5.3 (Review Manager 5.3). We based the display on a recent trial of what review users prefer (Carrasco‐Labra 2015).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The search identified 1183 unique references after we removed duplicates. After screening the abstracts, we excluded 1112 articles, and we assessed the remaining 71 full‐text articles formally for eligibility against the inclusion criteria (see Figure 2).

Included studies

We included eight cluster‐randomized trials in this review; 281 communities and 55,157 participants were enrolled. The cluster size ranged from 18 to 461 participants. One trial was conducted in Latin America (Chile, Cabezón 2005 CHL), two trials in Europe (England (Stephenson 2008 GBR), and Scotland (Henderson 2007 GBR)), and five in sub‐Saharan Africa (Malawi (Baird 2012 MWI), Zimbabwe (Cowan 2010 ZWE), Kenya (Duflo 2015 KEN), South Africa (Jemmott 2015 ZAF), and Tanzania (Ross 2007 TZA). Of those conducted in Africa, two were in rural areas (Cowan 2010 ZWE; Ross 2007 TZA), and three were in both rural and urban areas (Baird 2012 MWI; Duflo 2015 KEN; Jemmott 2015 ZAF).

All included trials were published between 2005 and 2015, with reported follow‐ups ranging from 18 months (Baird 2012 MWI), to seven years (Duflo 2015 KEN; Stephenson 2008 GBR).

Seven of the eight trials included a specific sexual and reproductive health educational component in the intervention and were based on a range of theoretical frameworks (Cabezón 2005 CHL; Cowan 2010 ZWE; Duflo 2015 KEN; Henderson 2007 GBR; Jemmott 2015 ZAF; Ross 2007 TZA; Stephenson 2008 GBR). These interventions focused specifically on changing knowledge, attitudes, behaviours, and norms related to sexual and reproductive health. The educational component ranged in intensity from three, one‐hour sessions in one school year (Stephenson 2008 GBR), to 36 sessions of 40 minutes over three school years (Ross 2007 TZA). Three trials incorporated trained peer educators into their intervention (Cowan 2010 ZWE; Ross 2007 TZA; Stephenson 2008 GBR), two incorporated nurse or health worker training to encourage 'youth friendly services' (Cowan 2010 ZWE; Ross 2007 TZA), and one included a parental training component (Cowan 2010 ZWE). Drama (including video dramas), games, or role play were incorporated into five of the intervention programmes (Cowan 2010 ZWE; Henderson 2007 GBR; Jemmott 2015 ZAF; Ross 2007 TZA; Stephenson 2008 GBR). Four of the seven trials reported some mention of gender roles (Cowan 2010 ZWE; Henderson 2007 GBR; Ross 2007 TZA; Stephenson 2008 GBR). Condoms were not given freely to participants in any of the trials, but were demonstrated to students in two trials (Henderson 2007 GBR; Stephenson 2008 GBR), and sold and marketed to young people in one trial (Ross 2007 TZA) (see Table 4: Description of educational interventions).

1. Description of educational interventions.

| Study (Country) | Target group | Target group education | Other components | Outcome measurement | |||

| Duration of intervention | Number of sessions | Delivered by | Content1 | ||||

| Cabezón 2005 CHL (Chile) | Girls (age 15 to 16 years) attending an all girls' high school | 1 year | 14 | Teachers | TeenSTAR programme focusing on abstinence, fertility awareness, and psychological and personal aspects of sexuality. | N/A | 3 years |

| Cowan 2010 ZWE (Zimbabwe) | Form 2 pupils (median age 15 years) | 3 years | Unclear 'both in‐and‐out of school' |

A school leaver (peer) who received training and supervision | A focus on developing knowledge and skills around sexual health issues. | A 22‐session community‐based programme for parents and community stakeholders aimed at improving communication with and community support of teenagers. A strand aimed at nurses and rural clinic workers aiming to improve accessibility of clinics to young people. |

4 years |

| Duflo 2015 KEN (Kenya) | 6th grade students (median age 13.5 years) | No details given | No details given | Teachers | Kenyan government's UNICEF/HIV/AIDS curriculum focusing on abstinence until marriage. | Health clubs to deliver HIV information outside the classroom. | 2 years 7 years |

| Henderson 2007 GBR (Great Britain) | 13‐15 year olds | 2 years | 20 | Teachers | Aimed to reduce unwanted pregnancies, reduce unsafe sex, and improve the quality of sexual relationships. | 5‐day training for teachers | 4.5 years |

| Jemmott 2015 ZAF (South Africa) | Grade 6 pupils (age range 9 to 18 years) |

6 days | 12 | Adult facilitators with 8 days of training | Mixed‐sex sessions involved games, brainstorming, role‐playing, group discussions, and comic workbooks with a series of characters and storylines. | Participants were given assignments to take home and to complete with parents. | 4.5 years |

| Ross 2007 TZA (Tanzania) | Primary school students (age range 14 to > 18 years) | 3 years | 36 | Teachers with peer assistants | Aimed to provide knowledge and skills to delay sexual debut, reduce sexual risk‐taking, and increase appropriate use of health services. | Health workers were trained for 1 week in the provision of youth‐friendly sexual and reproductive health services and supervised quarterly. Community mobilization activities including annual youth health weeks, interschool competitions and performances, and quarterly video shows. |

3 years |

| Stephenson 2008 GBR (Great Britain) | Year 9 pupils (age 13 to 14 years) | 4 months | 3 | Peers | Aimed at improving skills in sexual communication and condom use and knowledge of pregnancy, STIs, contraception, and local health services. | N/A | 7 years |

1None of the interventions included free distribution of condoms.

Abbreviations: N/A: not applicable ; STI: sexually transmitted infection.

One trial, and a trial within one of the studies, had no specific educational component, and used only a conditional or unconditional cash transfer as the intervention (Baird 2012 MWI), or two free school uniforms over a period of 18 months (Duflo 2015 KEN). These interventions were an attempt to influence the 'upstream factors' that affect reproductive health outcomes, such school attendance, poverty, and inequality (see Table 5: Description of incentive interventions).

2. Description of incentive‐based interventions.

| Study ID (Country) | Target group | Incentive‐based components | Outcome measurement | |||

| Type | Size | Conditional | Frequency | |||

| Baird 2012 MWI(Malawi) | Never married girls (age 13 to 22 years) |

Cash | USD 1 to 5 to the participant and USD 4 to 10 to her family |

Yes | Monthly | 1.5 years |

| Duflo 2015 KEN(Kenya) | 6th grade students (median age 13.5 years) | School uniform | — | No | At start of school year and 18 months later | 2 years 7 years |

Biological outcomes such as HIV, herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV2) (and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs)), were measured by dried blood spots and laboratory tests (Baird 2012 MWI; Cowan 2010 ZWE; Duflo 2015 KEN; Ross 2007 TZA), or blood sera and urine tests (Jemmott 2015 ZAF), and participants were provided treatment, counselling, and follow‐up as necessary. Current pregnancy was measured by urine sample (Ross 2007 TZA), or school reports with follow‐up home visits (Duflo 2015 KEN), whilst pregnancy at follow‐up was measured by linkage to health service records (Henderson 2007 GBR; Stephenson 2008 GBR), or school reports (Cabezón 2005 CHL; Duflo 2015 KEN), with follow‐up home visits (Duflo 2015 KEN).

Excluded studies

We excluded 63 studies (see the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table); a further five trials are ongoing, or have been completed, but have not reported their results in peer‐reviewed publications (see the 'Characteristics of ongoing studies' table).

Risk of bias in included studies

We have summarized the 'Risk of bias' assessments in Figure 3.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item for each included study.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

Baird 2012 MWI, Duflo 2015 KEN, Ross 2007 TZA, and Stephenson 2008 GBR utilized a computer‐generated random sequence and we deemed them to be at low risk of bias. We judged Cabezón 2005 CHL to be at high risk of bias, as classes were alternately selected by choosing a letter of the class from a bag, and the remaining trials were at unclear risk due to inadequate description of methods (Cowan 2010 ZWE; Henderson 2007 GBR; Jemmott 2015 ZAF).

Recruitment bias

We considered Baird 2012 MWI, Duflo 2015 KEN and Ross 2007 TZA to be at low risk of recruitment bias as individuals were recruited and baseline surveys were completed before the randomization of enumeration areas. We judged Cowan 2010 ZWE, Henderson 2007 GBR, Jemmott 2015 ZAF and Stephenson 2008 GBR to be at unclear risk of recruitment bias, as clusters were randomized first and then individuals were recruited from those clusters. Cabezón 2005 CHL only requested informed consent from parents of girls in the intervention group, and we therefore deemed it to be at high risk of recruitment bias.

Baseline imbalance

Cowan 2010 ZWE, Duflo 2015 KEN, Ross 2007 TZA, and Stephenson 2008 GBR all reported baseline measurements of outcomes between intervention and control participants and there were no baseline imbalances reported, therefore we judged them to be at low risk of bias. We deemed Baird 2012 MWI, Henderson 2007 GBR and Jemmott 2015 ZAF to be at unclear risk of bias for baseline imbalance. Baird 2012 MWI reported that, at baseline, schoolgirls in the intervention group were more likely to report unprotected sexual intercourse than those in the control group. Furthermore, the main outcome measures, HIV and HSV2, were not measured at baseline. Henderson 2007 GBR reported a slight gender imbalance at baseline and also an imbalance in those who reported sexual activity between the intervention and control groups. Jemmott 2015 ZAF reported 'some imbalance' at baseline, but provided no further details. We deemed Cabezón 2005 CHL to be at high risk of bias as there was baseline imbalance in the incidence of pregnancy between the intervention and control groups in the 1997 cohort, with no pregnancies in the intervention group and six in the control group.

Allocation concealment

We judged both Jemmott 2015 ZAF and Ross 2007 TZA to be at low risk of bias for allocation concealment as they reported concealing allocation up to the point of assignment. We judged Baird 2012 MWI, Cowan 2010 ZWE, Duflo 2015 KEN, Henderson 2007 GBR, and Stephenson 2008 GBR to be at an unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment, as the trial authors did not describe this in any detail. We judged one trial to be at a high risk of bias for allocation concealment (Cabezón 2005 CHL), as classes were chosen alternately and therefore assignment was unlikely to have been concealed adequately.

Blinding

Baird 2012 MWI and colleagues mentioned that they did not mask students to their assignment, and it became apparent that some participants had friends or acquaintances in other groups. However as it was not an educational intervention but rather a cash transfer incentive‐based programme there was no chance of 'contamination'. Furthermore, although participants were aware of whether they were receiving cash, how much, and whether it was conditional or not, they were not aware that the primary outcomes were related to HIV/STI prevalence. Baird 2012 MWI did not mask the investigators that conducted statistical analyses and did not describe blinding of the assessors who gathered samples. Overall, we deemed the trial as at an unclear risk of bias for performance and detection bias. Only Stephenson 2008 GBR described the process of blind matching of participants to routine National Health Service (NHS) data, and therefore we judged it to be at low risk of bias for the purposes of this Cochrane Review for detection bias, but unclear for performance bias. It is often difficult to blind participants and personnel in cluster‐RCTs within schools and communities, as a number of trial authors noted (Henderson 2007 GBR; Jemmott 2015 ZAF; Stephenson 2008 GBR). Trial authors did not report blinding of participants or personnel (Cabezón 2005 CHL; Cowan 2010 ZWE; Henderson 2007 GBR; Jemmott 2015 ZAF; Ross 2007 TZA), or said that it was not possible to blind teachers who attended a training course to deliver the intervention (Duflo 2015 KEN; Henderson 2007 GBR). Therefore, we judged these trials to be at an unclear risk of bias (Cabezón 2005 CHL; Cowan 2010 ZWE; Duflo 2015 KEN; Henderson 2007 GBR; Jemmott 2015 ZAF; Ross 2007 TZA).

Incomplete outcome data

We judged Baird 2012 MWI, Duflo 2015 KEN, Henderson 2007 GBR, Jemmott 2015 ZAF and Ross 2007 TZA to be at low risk of bias for this domain, as loss to follow‐up was similar in both intervention and control groups amongst those selected for follow‐up, and these trials performed intention‐to‐treat analyses. We deemed Henderson 2007 GBR to be at low risk of bias for objective outcomes, as follow‐up was equal across both trial arms (99.6% intervention, 99.5% control). A small level of attrition may have occurred due to women attending private clinics (less than 2% terminations) or having terminations in England or Wales (2.7%). There is no reason to expect this would differ across trial arms. However, we deemed Henderson 2007 GBR to be at high risk of bias for self‐reported outcomes due to a very low rate of response (41% control, 38% intervention). A systematic under‐representation of school leavers may have biased the result towards the null hypothesis. We deemed Ross 2007 TZA to be at low risk of bias due to similar attrition rates across control (72%) and intervention (74%) arms. Stephenson 2008 GBR conducted an intention‐to‐treat analysis. Missing data for objective measures meant that 28% of the control girls and 21% of the trial girls (P value 0.21) could not be matched with abortion data. It is possible that this may have biased the result towards the null hypothesis, but this risk appears to be small. Cabezón 2005 CHL reported that loss to follow‐up was 'similar' across intervention and control groups, but provided no data to support this, so we judged the trial to be at an unclear risk of bias. Cowan 2010 ZWE reported that interim survey results revealed a high rate of outmigration (46%) from the original cohort, so the design of the trial was altered and resulted in a cross‐sectional study. As a result, the proportion of the original cohort members included in the final survey was unlikely to have been more than 7%. This very high loss to follow‐up left all outcome measures and the study prone to a high risk of bias.

Selective reporting

We judged six trials to be at low risk of bias (Baird 2012 MWI; Cowan 2010 ZWE; Duflo 2015 KEN, Henderson 2007 GBR; Ross 2007 TZA; Stephenson 2008 GBR), as the trial authors reported all of the outcomes stated in their methods section. We judged Cabezón 2005 CHL to be at high risk of bias as the measurement of pregnancy rates was obtained from school records, and it is unlikely that all pregnancies were reported. Jemmott 2015 ZAF did not include complete details of the outcome data related to the biological outcomes measured (HIV, HSV2 and other STIs) in the published paper and so we judged it to be at high risk of bias.

Other potential sources of bias

We considered Baird 2012 MWI, Duflo 2015 KEN, Henderson 2007 GBR, Ross 2007 TZA, and Stephenson 2008 GBR to have a low risk of bias for this domain, as we found no other potential sources of bias. Jemmott 2015 ZAF did not describe their method of choosing schools that were eligible in sufficient detail, so we deemed the trial to be at an unclear risk of bias. We judged Cabezón 2005 CHL to be at high risk of bias. As abortion in Chile is illegal, it is unlikely that pregnancy and abortion would be reported fully to schools. Cowan 2010 ZWE reported that it became difficult to implement the programme in schools for political reasons, and that this coincided with a fall in school attendance for economic reasons and substantial outmigration from the country. Therefore we judged this trial as having a high risk of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Educational interventions versus no intervention.

| Educational programmes to reduce HIV, STIs, and pregnancy in adolescents | |||||

| Patient or population: adolescents Settings: schools and communities Intervention: sexual and reproductive health educational interventions delivered through schools Control: no intervention Outcomes: confirmed biologically by blood or urine test | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (trials) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Control | Sexual and reproductive health education | ||||

|

HIV prevalence Follow‐up: 18 months to 3 years |

10 per 1000 |

10 per 1000 (8 to 13) |

RR 1.03 (0.80 to 1.32) |

14,163 (3 trials) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2,3,4 |

|

HSV2 prevalence Follow‐up: 18 months to 3 years |

110 per 1000 |

114 per 1000 (103 to 127) |

RR 1.04 (0.94 to 1.15) |

17,445 (3 trials) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1,2,3,5 |

| Syphillis prevalence Follow‐up: 18 months to 3 years | 30 per 1000 |

24 per 1000 (14 to 42) |

RR 0.81 (0.47 to 1.39) |

6977 (1 trial) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,6,7 |

| Pregnant at end of trial Follow‐up: mean 3 years | 90 per 1000 |

89 per 1000 (77 to 104) |

RR 0.99 (0.85 to 1.16) |

8280 (3 trials) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1,2,3,5 |

| The assumed risk is taken from the median control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; HSV2: herpes simplex virus‐2; RR: risk ratio; STI: sexually transmitted infection. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1No serious risk of bias: none of the trials described blinding of outcome assessors but this deficiency was not considered serious enough to downgrade. 2No serious inconsistency: none of these trials found a statistically significant effect. Statistical heterogeneity was low. 3Downgraded by 1 level for serious indirectness: these trials were conducted in schools in low‐income countries, and had extensive programmes of sexuality education including peers, teachers, and communities. However, the findings are not easily generalized to other programmes or settings. 4Downgraded by 1 level for imprecision: due to the low prevalence of HIV in these trials, both the trials and the meta‐analysis remain underpowered to allow confident exclusion of small but clinically important effects. 5No serious imprecision: the meta‐analysis is adequately powered to look for a 25% relative reduction, and the 95% CI is narrow and probably excludes clinically important effects. 6Downgraded by 1 level for serious indirectness: only a single trial from Tanzania evaluated this outcome. This does not exclude effects with different programmes in different settings. 7Downgraded by 1 level for serious imprecision: the 95% CI is wide and includes both clinically important effects and no effect.

Summary of findings 2. Incentive‐based programmes versus no intervention.

| School‐based incentive programmes to reduce HIV, STIs, and pregnancy in adolescents | |||||

|

Patient or population: adolescents

Settings: school and communities

Intervention: incentive‐based programmes delivered through schools which aim to reduce HIV and STI among adolescents

Control: no intervention Outcomes: confirmed biologically by blood or urine test | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (trials) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Control | Incentive programmes | ||||

|

HIV prevalence Follow‐up: 18 months to 3 years |

10 per 1000 |

12 per 1000 (5 to 30) |

RR 1.23 (0.51 to 2.96) |

3805 (2 trials) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2,3,4 |

| HSV2 prevalence Follow‐up: 18 months to 3 years | Not calculated | Not calculated | Not calculated | 7229 (2 trials) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,3,5 |

| Syphillis prevalence Follow‐up: 18 months to 3 years | 30 per 1000 |

12 per 1000 (2 to 98) |

RR 0.41 (0.05 to 3.27) |

1291 (1 trial) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,6,7 |

| Pregnant at end of trial Follow‐up: mean 3 years | 90 per 1000 |

68 per 1000 (52 to 89) |

RR 0.76 (0.58 to 0.99) |

4200 (2 trials) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2,3,8 |

| The assumed risk is taken from the median control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; HSV2: herpes simplex virus‐2; RR: risk ratio; STI: sexually transmitted infection. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1No serious risk of bias: neither of these trials described blinding of outcome assessors. However, this deficiency was not serious enough to downgrade. 2No serious inconsistency: statistical heterogeneity was low. 3Downgraded by 1 level for serious indirectness: these two trials were conducted in Malawi and Kenya, and used very different interventions. Baird 2012 MWI gave a monthly cash transfer while Duflo 2015 KEN provided free school uniforms. It is difficult to extrapolate these result to different settings. 4Downgraded by 1 level for imprecision: due to the low prevalence of HIV in these trials, both the trials and the meta‐analysis remain underpowered to allow confident exclusion of small but clinically important effects. 5Downgraded by 2 levels for serious inconsistency: Baird 2012 MWI reported a statistically significant reduction in HSV2 in young women, whereas Duflo 2015 KEN found no effect in either males or females alone or combined into one mixed gender group. 6Downgraded by 1 level for serious indirectness: only a single trial assessed this outcome. The lack of effect does not exclude the possibility of effects in other settings. 7Downgraded by 2 levels for serious imprecision: the prevalence of syphilis was very low and consequently the trial is underpowered to confidently exclude small but clinically important effects. 8Downgraded by 1 level for serious imprecision: the 95% CI is wide and includes both important effects and negligible effects.

Summary of findings 3. Combined incentive‐based and educational interventions versus no intervention.

| School‐based combined incentive and educational programmes to reduce HIV, STIs, and pregnancy in adolescents | |||||

|

Patient or population: adolescents

Settings: school and communities

Intervention: incentives to promote school attendance plus sexual and reproductive health education

Control: no intervention Outcomes: confirmed biologically by blood or urine test | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (trials) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Control | Incentive programmes | ||||

|

HIV prevalence Follow‐up: 18 months to 3 years |

10 per 1000 |

15 per 1000 (5 to 51) |

RR 1.53 (0.45 to 5.13) |

2506 (1 trial) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2,3 |

| HSV2 prevalence Follow‐up: 18 months to 3 years | 110 per 1000 |

90 per 1000 (75 to 109) |

RR 0.82 (0.68 to 0.99) |

5899 (1 trial) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2,3 |

| Syphillis prevalence Follow‐up: 18 months to 3 years | — | — | — | — (0 trials) | — |

| Pregnant at end of trial Follow‐up: mean 3 years | 90 per 1000 |

81 per 1000 (60 to 107) |

RR 0.90 (0.67 to 1.19) |

2782 (1 trial) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2,3 |

| The assumed risk is taken from the median control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval; HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus; HSV2: herpes simplex virus‐2; RR: risk ratio; STI: sexually transmitted infection. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1No serious risk of bias: this trial did not describe blinding of outcome assessors. However, this deficiency was not serious enough to downgrade. 2Downgraded by 1 level for serious indirectness: only a single trial assessed this outcome and consequently the results are difficult to extrapolate to different settings or alternative incentives or educational programmes. 3Downgraded by 1 level for serious imprecision: the 95% CI is wide and includes both important effects and negligible or no effect.

Comparison 1: School‐based educational interventions versus no intervention

Six trials evaluated school‐based educational interventions and reported biologically confirmed outcomes (Cabezón 2005 CHL; Cowan 2010 ZWE; Duflo 2015 KEN; Henderson 2007 GBR; Ross 2007 TZA; Stephenson 2008 GBR). One additional trial reported that these outcomes were measured, but did not report the data (Jemmott 2015 ZAF). We have requested the data from the trial authors but have received no response. Duflo 2015 KEN was a four‐arm trial in which one trial arm received an educational intervention that we included in Comparison 1. This trial also included an incentive programme, the results of which we have reported in Comparison 2, as well as a combined incentive and educational programme that is reported in Comparison 3.

HIV incidence and prevalence

Only Ross 2007 TZA measured HIV incidence. The incidence of HIV was low with no statistically significant differences between intervention and control groups in young women (16/1448 intervention group versus 24/1492 control group), or young men (3/2076 intervention group versus 2/2024 control group).

Three trials measured HIV prevalence at the end of follow‐up (Cowan 2010 ZWE; Duflo 2015 KEN; Ross 2007 TZA). In these trials, there were no demonstrable effects on the prevalence of HIV in young women or young men, or both sexes combined (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.32; three trials, 14,163 participants; Analysis 1.1). Although the effect estimate is close to no effect, the 95% confidence interval (CI) is wide, and larger studies may be necessary to fully exclude the possibility of small effects.

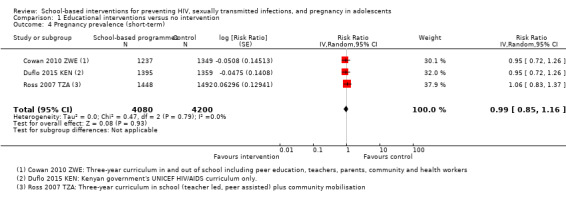

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Educational interventions versus no intervention, Outcome 1 HIV prevalence.

Note that although Ross 2007 TZA did not measure HIV prevalence, we were able to calculate prevalence based on the reported baseline prevalence and the incidence rate. This is based on the assumption that those who had HIV at baseline (or subsequently developed HIV during the study) were still living with HIV at the end of the study.

Other sexually transmitted infections

Three trials measured and reported HSV2 prevalence at the end of follow‐up. Across all three trials there were no demonstrable effects in either young women, young men, or both sexes combined (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.15; three trials, 17,445 participants; Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Educational interventions versus no intervention, Outcome 2 HSV2 prevalence.

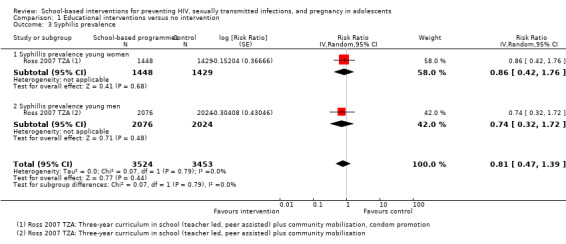

Only Ross 2007 TZA measured and reported the prevalence of syphilis at the end of follow‐up. Although the prevalence was lower in the intervention group, the 95% CI is wide and includes the possibility of no effect for young women, young men, and both sexes combined (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.39; one trial, 6977 participants; Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Educational interventions versus no intervention, Outcome 3 Syphilis prevalence.

Pregnancy

Three trials measured short‐term pregnancy prevalence through either urine testing (Cowan 2010 ZWE; Ross 2007 TZA), or school reports and home visits (Duflo 2015 KEN) of female participants within the trial. There were no apparent effects in individual trials or all trials combined (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.16; three trials, 8280 participants; Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Educational interventions versus no intervention, Outcome 4 Pregnancy prevalence (short‐term).

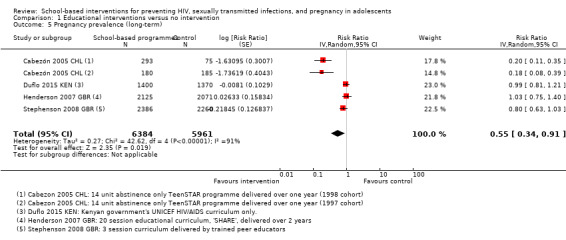

Four trials measured long‐term pregnancy prevalence. Two trials measured this outcome using health service data with biologically confirmed pregnancies (Henderson 2007 GBR; Stephenson 2008 GBR), while the other two trials relied on school reports and records (Cabezón 2005 CHL; Duflo 2015 KEN). There was an apparent reduction in long‐term pregnancy prevalence (RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.91; Analysis 1.5). Of these trials, only Cabezón 2005 CHL reported an effect that reached standard levels of statistical significance, and this effect was consistent for both cohorts, (RR 0.20, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.35 and RR 0.18, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.39). However, we deemed this trial to be at a high risk of bias and when this study was excluded there was no effect on long‐term pregnancy prevalence for the remaining trials (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.08; three trials, 11, 612 participants).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Educational interventions versus no intervention, Outcome 5 Pregnancy prevalence (long‐term).

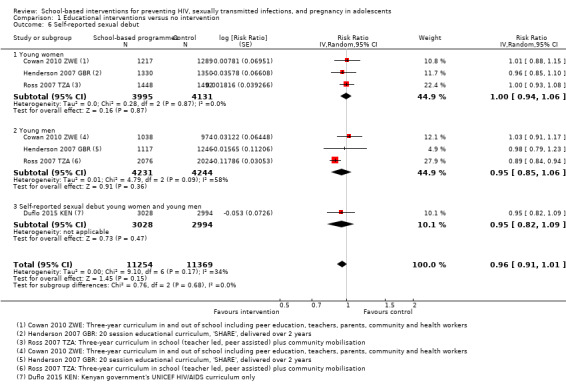

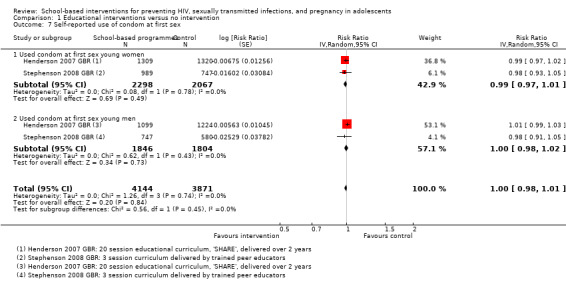

Self‐reported measures of behaviour change

Six trials also collected data on secondary measures of self‐reported behaviour change (Cowan 2010 ZWE; Duflo 2015 KEN; Henderson 2007 GBR; Jemmott 2015 ZAF; Ross 2007 TZA; Stephenson 2008 GBR). Across these trials there was no demonstrable effect on the number of young people reporting their first sexual encounter during the trial period (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.01; four trials, 22,623 participants; Analysis 1.6). There was also no evidence of an effect on the proportion of young people using a condom during their first sexual encounter (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.01; two trials, 8015 participants; Analysis 1.7), or using a condom during their most recent sexual encounter (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.03; six trials, 18,795 participants; Analysis 1.8). Although the exact outcome measurement varied between trials, statistical heterogeneity between trials was low.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Educational interventions versus no intervention, Outcome 6 Self‐reported sexual debut.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Educational interventions versus no intervention, Outcome 7 Self‐reported use of condom at first sex.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Educational interventions versus no intervention, Outcome 8 Self‐reported use of condom at last sex.

Comparison 2: Incentive programmes versus no intervention

Two trials evaluated incentive‐based programmes to encourage school attendance (Baird 2012 MWI; Duflo 2015 KEN).

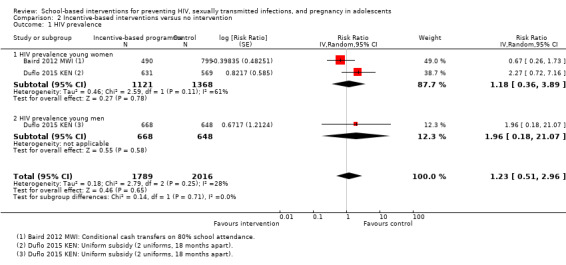

HIV prevalence

There were no demonstrable effects on the prevalence of HIV in young women or men in either trial, or in the trials combined (RR 1.23, 95% CI 0.51 to 2.96; two trials, 3805 participants; Analysis 2.1). However, the prevalence of HIV was low, and consequently the trials are underpowered to exclude clinically important effects with confidence.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Incentive‐based interventions versus no intervention, Outcome 1 HIV prevalence.

Baird 2012 MWI measured HIV prevalence amongst girls attending school, and those who had dropped out. However, the trial was not powered to detect effects in school dropouts, and because our analysis was aimed primarily at school‐based interventions, we have only included the schoolgirl cohort in all of our analyses. In the published paper Baird reported that the effect of HIV prevalence was statistically significant (HIV tests were positive in 7/490 intervention schoolgirls and 17/799 control schoolgirls at follow‐up).

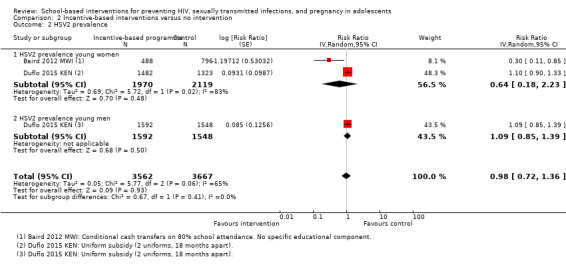

Other sexually transmitted diseases

Both trials reported HSV2 prevalence at the end of the trial. Of these, Baird 2012 MWI reported a reduction in HSV2 prevalence in young women (RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.85), based on 5/488 intervention schoolgirls testing positive compared to 27/796 control schoolgirls. However, it is important to note that Baird did not measure, or report HSV2 prevalence at baseline. No effect was apparent in young women or young men in the other trial (Duflo 2015 KEN), or when we combined the two trials (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.36; two trials, 7229 participants; Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Incentive‐based interventions versus no intervention, Outcome 2 HSV2 prevalence.

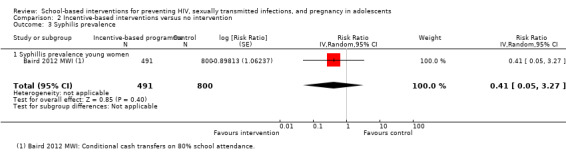

Only Baird 2012 MWI assessed the prevalence of syphilis, and the prevalence was too low to demonstrate effects (1/491 intervention schoolgirls versus 4/800 control schoolgirls; Analysis 2.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Incentive‐based interventions versus no intervention, Outcome 3 Syphilis prevalence.

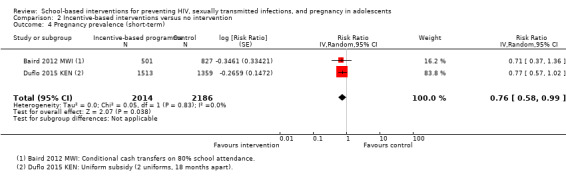

Pregnancy

Both trials measured short‐term pregnancy prevalence. Overall, pregnancy was reduced by around a quarter in those who received incentives (116/2014 intervention versus 151/2186 control; RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.58 to 0.99; two trials, 4200 participants; Analysis 2.4). The effect size was consistent across trials, but with wide CIs which include no effect.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Incentive‐based interventions versus no intervention, Outcome 4 Pregnancy prevalence (short‐term).

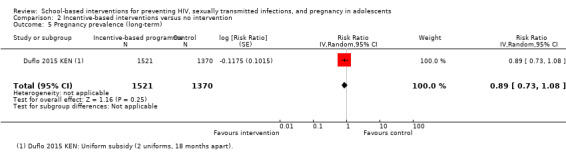

Only Duflo 2015 KEN measured the incidence of pregnancy throughout the long‐term follow‐up period up to seven years, and did not demonstrate an effect (604/1521 intervention versus 583/1370 control; RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.08; one trial, 2891 participants; Analysis 2.5).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Incentive‐based interventions versus no intervention, Outcome 5 Pregnancy prevalence (long‐term).

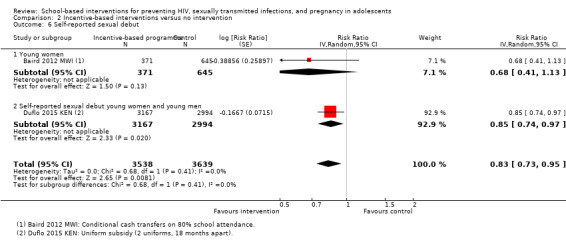

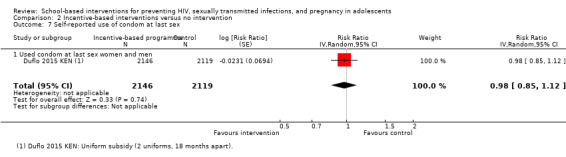

Self‐reported measures of behaviour change

Both trials collected data on secondary measures of self‐reported behaviour change. There was a reduction in the proportion of young people reporting their first sexual encounter (sexual debut) during the trial period (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.95; two trials, 7177 participants; Analysis 2.6). Only Duflo 2015 KEN, reported on the proportion using a condom during their most recent sexual encounter and demonstrated no reduction (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.12; one trial, 4265 participants, Analysis 2.7).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Incentive‐based interventions versus no intervention, Outcome 6 Self‐reported sexual debut.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Incentive‐based interventions versus no intervention, Outcome 7 Self‐reported use of condom at last sex.

Comparison 3: Combined incentive and educational programmes

Duflo 2015 KEN was a four‐arm trial that also included a trial arm in which participants received both free school uniforms and a programme of sexual and reproductive health education.

HIV prevalence

There were no demonstrable effects on HIV prevalence (RR 1.53, 95% CI 0.45 to 5.13; 1 trial, 2506 participants; Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Combined incentive‐based and educational interventions versus no intervention, Outcome 1 HIV prevalence.

Other sexually transmitted diseases

The prevalence of herpes simplex virus infection was lower in those receiving an incentive and educational programme combined compared to controls (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.99; one trial, 5899 participants, Analysis 3.2), and this reduction was mainly in young women (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.93).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Combined incentive‐based and educational interventions versus no intervention, Outcome 2 HSV2 prevalence.

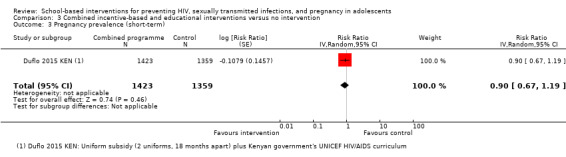

Pregnancy

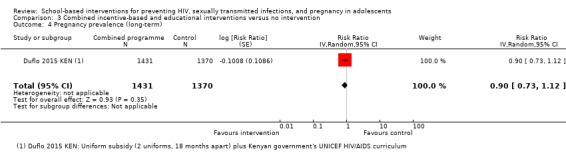

No effect was demonstrated either on the proportion of young women pregnant in the short‐term (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.19; one trial, 2782 participants; Analysis 3.3), or the incidence of pregnancy at the long‐term follow up (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.12; one trial, 2801 participants; Analysis 3.4).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Combined incentive‐based and educational interventions versus no intervention, Outcome 3 Pregnancy prevalence (short‐term).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Combined incentive‐based and educational interventions versus no intervention, Outcome 4 Pregnancy prevalence (long‐term).

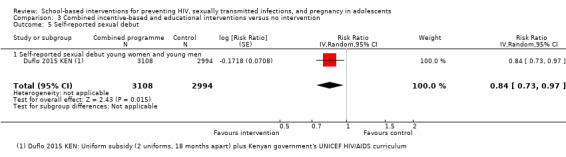

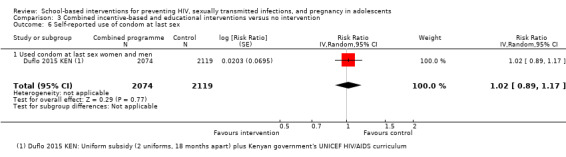

Self‐reported measures of behaviour change

The proportion of young people reporting their sexual debut during the trial was lower in those receiving the intervention (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.97; one trial, 6102 participants; Analysis 3.5), but there was no effect demonstrated on the proportion of adolescents using a condom during their most recent sexual encounter (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.17; one trial, 4193 participants; Analysis 3.6).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Combined incentive‐based and educational interventions versus no intervention, Outcome 5 Self‐reported sexual debut.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Combined incentive‐based and educational interventions versus no intervention, Outcome 6 Self‐reported use of condom at last sex.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Sexual and reproductive health educational programmes

In these trials, the educational programmes evaluated had no demonstrable effect on the prevalence of HIV (low certainty evidence), or other sexually transmitted infections (Herpes Simplex virus prevalence: moderate certainty evidence; Syphilis prevalence: low certainty evidence). There was also no apparent effect on the number of young women who were pregnant at the end of the trial (moderate certainty evidence).

Material or monetary incentive‐based programmes to promote school attendance

In these two trials, the incentives used had no demonstrable effect on the prevalence of HIV (low certainty evidence). Compared to controls, the prevalence of Herpes Simplex virus infection was lower in young women receiving a monthly cash incentive to stay in school, but not in young people given free school uniforms (very low certainty evidence). Only one trial evaluated the effects on syphilis and the prevalence was too low to confidently detect or exclude effects (very low certainty evidence). However, the number of young women who were pregnant at the end of the trial was lower among those who received incentives (low certainty evidence).

Combined material or monetary incentive‐based and educational programmes

One trial used a combined approach; this showed there was no demonstrable effect on the prevalence of HIV (low certainty evidence). Compared to controls, the prevalence of HSV infection was lower for those receiving free school uniforms to stay in school and an educational programme (low certainty evidence). The provision of a combined programme had no demonstrable effect on the number of young women who were pregnant at both short‐ and long‐term follow‐up (low certainty evidence).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The trials included in this review evaluated educational programmes that incorporated many of the specific characteristics that have previously been recommended for well‐designed adolescent sexual and reproductive health interventions (Kirby 2006). However, despite this, they failed to demonstrate any reduction in the prevalence of STIs or adolescent pregnancy. It is only possible to theorize about the potential reasons for this, but three factors may be important.

Firstly, the trials could simply be underpowered for the detection of small but clinically important effects. This could certainly be true for the lack of effect on HIV. Even in geographical settings where HIV is more common than elsewhere, the incidence during adolescence is relatively low and very large trials would be required to exclude small effects with confidence (see Table 6). For more common outcomes though, such as HSV2 and pregnancy, the trials are adequately powered to detect effects, and the effect estimate is close to zero with narrow 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Importantly, if the interventions are not reducing these more common outcomes, they are unlikely to be having an impact on HIV.

3. Optimal information size calculations.

| Outcome | Assumed risk1 | Clinically important relative reduction | Sample size required2,3 |

| HIV prevalence | 10/1000 (1%) | 25% | 43,576 |

| HIV prevalence | 10/1000 (1%) | 50% | 9344 |

| HSV2 prevalence | 110/1000 (11%) | 25% | 3606 |

| Syphilis prevalence | 30/1000 (3%) | 25% | 14,264 |

| Pregnancy | 90/1000 (9%) | 25% | 4494 |

1The assumed risk is the median control group risk from the included studies. 2We based all calculations on 2‐sided tests, with a ratio of 1:1, power of 0.8, and confidence level of 0.05. 3We performed all calculations using www.sealedenvelope.com/power/binary‐superiority.

Secondly, despite the effort that went in to designing these educational programmes, they may still have failed to address some areas critical to effecting change. For instance, it is unclear to what extent the programmes incorporated discussion of exploitation or violence, or whether the messages were adapted appropriately for both the male and female students. Furthermore, none gave condoms freely to participants. It is therefore not possible to say that educational programmes would never work, only that these programmes did not, despite extensive efforts to develop multifaceted approaches through formative consultation with young people themselves (Henderson 2007 GBR; Ross 2007 TZA; Stephenson 2008 GBR).

The third possible explanation is that educational programmes alone do not address the wider structural issues that influence sexual health outcomes, sexual behaviour and risk taking; the availability and affordability of schools and health services, contraceptive choice and condoms, poverty, and cultural gender norms. Indeed it is this third factor which has led some to develop and promote interventions which prioritize school attendance and educational achievement.

This review included two trials that promoted school attendance through cash transfers, and free school uniforms respectively (Baird 2012 MWI; Duflo 2015 KEN). Further trials are currently ongoing (Pettifor 2016), or have not yet reported their results (NCT01187979; NCT01233531). The two early trials have had some positive, but conflicting findings, which should temper enthusiasm for this approach until the results of these additional trials have been published. Baird 2012 MWI found a reduction in HSV2 prevalence in girls given monthly cash incentives, while Duflo 2015 KEN did not reproduce this effect with free school uniforms. Similarly, while both cash incentives and free school uniforms were associated with a reduction in adolescent pregnancies, a third trial arm in Duflo 2015 KEN, which received both free school uniforms and an educational intervention, did not have a lower incidence of pregnancy. This is counter‐intuitive and further trials will help us to understand why.

Quality of the evidence

We assessed the quality or certainty in the evidence using the GRADE approach, which we have presented in the 'Summary of findings' tables (Table 1; Table 2).

For educational programmes we have moderate certainty that these programmes do not have an impact on either STIs or pregnancy. As described above, we downgraded the certainty for indirectness, as we are unable to extrapolate the findings of these few trials in specific settings confidently to all educational programmes everywhere. For the finding of no effect on HIV prevalence we further downgraded the evidence to low certainty under 'imprecision', as the prevalence of HIV was generally low in these trials and very large trials would be needed to exclude fully the possibility of small but clinically important effects.

For incentive‐based programmes, our level of certainty is low or very low due to the limited number of trials available (which affects both precision and directness) and the inconsistencies in the findings of the two available trials. There are currently several more trials of incentive‐based programmes underway, and we would expect that certainty about the presence or absence of effects will be increased in future editions of this review.

Potential biases in the review process

We used only peer‐reviewed trials in this review. It is unlikely that we missed papers that were unpublished that included biological outcomes, as this is a relatively new innovation in adolescent sexual and reproductive health research and it is likely that they would be published. Most intervention studies of this kind use self‐reported measures only.

The missing data from Jemmott 2015 ZAF are unlikely to have affected the overall findings, however, the findings on pregnancy at long‐term follow‐up were sensitive to the exclusion of Cabezón 2005 CHL. The potential for a high risk of bias in this study suggests that the study authors' conclusions should be treated with caution.

All eight of the cluster‐randomized controlled trials (cluster‐RCTs) reported that they took account of the cluster randomization. However, not all of them included the intraclass correlation (ICC) or design effect. Therefore, we recalculated the standard errors reported and use these in our meta‐analyses.

We have only included RCTs. Before‐and‐after studies are often used for public health interventions, but when we deemed that there were enough RCTs for this analysis, we decided that the inclusion of studies with less robust designs was unlikely to add anything further.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The conclusions of this Cochrane Review are consistent with previous published reviews of curriculum‐based educational programmes. The Health Technology Assessment Centre’s systematic review of school‐based interventions to prevent STIs including HIV included RCTs and assessed sexual risk behaviour outcomes (Shepherd 2010). The review authors identified few statistically significant effects on behaviour in the included studies. Where there were significant effects, they often only applied to a subgroup of the participants (boys only or girls only, or only the subgroup who became sexually active during the study period). This led them to conclude that “school‐based behavioural interventions for the prevention of STIs in young people can bring about improvements in knowledge and increased self‐efficacy, but the interventions did not significantly influence sexual risk‐taking behaviour or infection rates”. The recent suggestion that the UK Govenment's Teenage Pregnancy Strategy which incorporated school‐based programmes and health service interventions has been effective in reducing adolescent pregnancy (Hadley 2016) is promising but needs further evidence from controlled studies, preferably with randomized designs, as temporal trends can confuse and mislead.

There now seems to be consensus that in sub‐Saharan Africa few curriculum‐based educational programmes have been shown to be effective, and many of the evaluations have a high risk of bias (Michielsen 2010; Paul 2008). The most recent systematic review of programmes for adolescents and young people based in schools and other settings, found 28 experimental studies, only 11 of which were RCTs, and many of which were judged to be of sub optimal quality (Michielsen 2010). This paucity of strong evidence regarding the effects of educational programmes in sub‐Saharan Africa on adolescent HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention is also consistent with the assessments of earlier reviews (Flisher 2008; Gallant 2004; Kirby 2007; Magnussen 2004; Michielsen 2010; Paul 2008), in that programmes that aimed at delaying sexual debut among adolescents and young people have been shown to have limited effectiveness. Our current knowledge of what works remains limited, especially for marginalized adolescents (Chandra‐Mouli 2015).

The finding that incentive‐based programmes that encourage school attendance may reduce pregnancy in adolescents confirms the results of a previous study which suggests that leaving school early was associated with early pregnancy (Imamura 2007).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.