Abstract

Rationale: Hospitalization for acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is associated with significant morbidity and health care costs, and hospitals in the United States are now penalized by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for excessive readmissions. Identifying patients at risk of readmission is important, but modifiable risk factors have not been clearly established, and the potential contributing role of psychological disease has not been examined adequately. We hypothesized that depression and anxiety would increase the risk of both short- and long-term readmissions for acute exacerbation of COPD.

Objectives: To characterize the associations between depression and anxiety and COPD readmission risk.

Methods: We examined the medical records for all patients with a primary diagnosis of acute exacerbation of COPD by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes admitted to the University of Alabama at Birmingham Hospital between November 2010 and October 2012. Those who did not meet the standardized study criteria for acute exacerbation of COPD and those with other respiratory illnesses as the primary diagnosis were excluded. Comorbidities were recorded on the basis of physician documentation of the diagnosis and/or the use of medications in the electronic medical record. Multivariable regression analyses identified factors associated with readmission for acute exacerbation of COPD at 1 year and within 30 and 90 days.

Measurements and Main Results: Four hundred twenty-two patients were included, with 132 readmitted in 1 year. Mean age was 64.8 ± 11.7 years, and mean percent predicted FEV1 was 48.1 ± 18.7%. On univariate analysis, readmitted patients had lower percent predicted FEV1 (44.9 ± 17.3% vs. 50.2 ± 19.4%; P = 0.05) and a higher frequency of depression (47.7% vs. 23.4%; P < 0.001). On multivariable analysis, 1-year readmission was independently associated with depression (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 2.67; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.59–4.47) and in-hospital tobacco cessation counseling (adjusted OR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.18–0.66). Depression also predicted readmission at 30 days (adjusted OR, 3.83; 95% CI, 1.84–7.96) and 90 days (adjusted OR, 2.47; 95% CI, 1.34–4.55).

Conclusions: Depression is an independent risk factor for both short- and long-term readmissions for acute exacerbation of COPD and may represent a modifiable risk factor. In-hospital tobacco cessation counseling was also associated with reduced 1-year readmission.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, exacerbations, risk, depression

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) accounts for significant morbidity and health care costs and is the third leading cause of death in the United States (1, 2). Acute exacerbations of COPD represent critical events in the course of this disease and are associated with decline in lung function, worse quality of life, and increased mortality (3–6). The majority of health care costs associated with COPD result from hospitalization (7, 8), and approximately one-half of patients hospitalized are readmitted for acute exacerbation within 1 year and up to 22% of patients within 30 days (9–11). Reducing 30-day readmissions for acute exacerbation of COPD has been recognized recently by the United States Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services as an important target for both physicians and health care systems (12, 13).

COPD is a complex multisystem disease with numerous physical and psychological processes causing acute exacerbations and influencing hospitalization (14–16). Previously described risk factors for readmission include age, FEV1, hypercarbia, functional status, and prior hospitalizations (11, 17–20), although most of these factors are not modifiable. Numerous medical comorbidities have also been associated with increased risk of readmission (17, 21), and recent literature suggests that a large proportion of COPD readmissions are not for acute exacerbations (12).

Although many medical comorbidities play a role in respiratory decompensation and rehospitalization (22, 23), the impact on readmissions of psychological comorbidities such as depression and anxiety, which are highly prevalent in patients with COPD and affect quality of life, remains largely unexplored (24, 25). In small cohorts, data showed that depressive symptoms in patients with COPD predicted exacerbation risk over 1 year (26, 27). We hypothesized that depression and anxiety would increase the risk of both short- and long-term readmissions because of acute exacerbation of COPD.

Methods

Study Design and Patient Selection

The medical records for patients admitted to the University of Alabama at Birmingham Hospital with a primary diagnosis of acute exacerbation of COPD by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes 491.21, 491.22, and 496 from November 2010 to October 2012 were reviewed. Three physicians (A.I., J.G., and J.W.) reviewed individual electronic medical records and excluded those patients who did not meet the standardized study criteria for acute exacerbation of COPD defined by increased dyspnea, increased cough, or purulent sputum present for at least 48 hours on admission in a patient with known COPD (28). Those with respiratory illnesses other than COPD as a primary diagnosis, such as lung cancer, bronchiectasis, and pneumonia, were also excluded. Acute exacerbation of COPD was defined similarly for readmissions.

Potential contributing comorbidities such as coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), depression, and anxiety were recorded. Comorbidities were defined either by physician diagnosis or by use of medications as documented in the electronic medical record. Clinical variables including laboratory values and vital signs were also recorded at the time of index admission. Immunization status for pneumococcal and influenza vaccines was recorded. Subjects were deemed to have received in-hospital tobacco cessation counseling if counseling from either physicians or tobacco cessation counselors was recorded in the chart. The Hospital Tobacco Consult Service at our center provided bedside smoking cessation counseling, together with pharmacotherapy prescriptions, to patients who were referred by their health care providers or who indicated at admission that they wanted to quit smoking, and patients were referred to the state quit line for follow-up. The consult staff assessed patients’ nicotine withdrawal discomfort, need for pharmacotherapy, and interest in quitting smoking, assisting those interested in developing a personalized quit plan. Patients provided with quit counseling were called within a month after discharge to encourage progress in quitting and use of the state quit line, if referred.

In the current analysis, we investigated risk factors for both short- and long-term readmission for acute exacerbation of COPD. We defined short-term readmission as readmission for acute exacerbation of COPD within 30 days and 90 days of index admission and long-term readmission as within 1 year. The institutional review board at the University of Alabama at Birmingham approved the study (X121221005).

Statistical Analysis

Baseline data were expressed as means with standard deviations (SD) for normally distributed values. Univariate analysis was performed using independent t test or Mann-Whitney U test where appropriate for comparing continuous variables and chi-square test for discrete variables for two groups defined by 1-year readmission status. Variables significant on univariate analysis (P < 0.05) were included in multivariable logistic regression analyses to identify independent predictors of readmission within 1 year of index admission. Additional variables found to be significant predictors of readmission in previous studies and important clinical variables such as age, race, sex, and smoking status were forced into the multivariable models. FEV1 data within 2 years before admission were available in one-half the subjects, and hence we performed a secondary sensitivity analysis by adding FEV1 to the multivariable model for 1-year readmission in this group. Because depression and anxiety can frequently coexist, collinearity diagnostics were performed using variance inflation factor (VIF) assessments. A VIF greater than 10 was considered significant for collinearity. Similar analyses were performed to identify predictors for 30-day and 90-day readmissions. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 20.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for all analysis. All statistical tests were two-sided, with significance assigned to tests with P < 0.05.

Results

Of the 901 patients discharged with primary International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes for acute exacerbation of COPD during the time period of the current analysis, 422 were confirmed by physician review to meet the study definition of exacerbation and to not have alternative primary respiratory illnesses, and were included in the study. These patients were separated into groups on the basis of 1-year readmission, as readmitted (n = 132) and non-readmitted (n = 290). As seen in Table 1, participants overall had a mean ± SD age of 64.8 ± 11.7 years. Of these, 146 (34.5%) were African American, and 212 (50.1%) were male. Mean percent predicted FEV1 was 48.1 ± 18.7%. Depression and anxiety were present in 131 patients (31%) and 89 patients (21%) in the cohort, respectively (Table 1). There was no collinearity between depression and anxiety (VIF = 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants by 1-yr readmission from index hospitalization

| Overall (N = 422) | Patients Not Readmitted (n = 290) | Patients Readmitted (n = 132) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 64.8 ± 11.7 | 65.1 ± 12.0 | 64.3 ± 11.3 | 0.52 |

| Male sex | 212 (50.1) | 74 (56.1) | 138 (47.6) | 0.11 |

| African American | 146 (34.5) | 99 (34.1) | 47 (35.6) | 0.30 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.6 ± 8.3 | 27.7 ± 8.3 | 27.2 ± 8.2 | 0.58 |

| Smoking history, pack-years | 50.0 ± 26 | 49.7 ± 27.2 | 50.6 ± 24.3 | 0.78 |

| Current smoker | 276 (65.2) | 188 (64.8) | 100 (67.1) | 0.74 |

| FEV1 (% predicted)* | 48.1 ± 18.7 | 50.2 ± 19.4 | 44.9 ± 17.3 | 0.05 |

| FEV1/FVC* | 52.5 ± 14.3 | 53.8 ± 14.9 | 50.6 ± 13.1 | 0.13 |

| Serum sodium, mmol/L | 136.7 ± 4.2 | 136.4 ± 4.3 | 137.4 ± 3.9 | 0.03 |

| Serum bicarbonate, mmol/L | 29.1 ± 7.0 | 28.9 ± 7.7 | 29.6 ± 5.3 | 0.36 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 0.55 |

| White blood cell count, 103/mm3 | 10.2 ± 4.7 | 10.3 ± 4.8 | 10.1 ± 4.6 | 0.63 |

| Hematocrit | 39.1 ± 6.1 | 39.3 ± 6.1 | 38.7 ± 6.3 | 0.37 |

| Coronary artery disease | 113 (26.7) | 73 (26.4) | 40 (31.0) | 0.34 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 54 (12.8) | 40 (14.4) | 14 (10.9) | 0.32 |

| Congestive heart failure | 107 (25.3) | 75 (26.4) | 32 (24.2) | 0.64 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 45 (10.6) | 30 (10.3) | 15 (11.4) | 0.75 |

| Hypertension | 296 (70.0) | 201 (69.3) | 95 (72.0) | 0.65 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 99 (23.4) | 73 (25.2) | 26 (19.7) | 0.22 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 51 (12.1) | 37 (12.8) | 14 (10.6) | 0.53 |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 44 (10.4) | 29 (10) | 15 (11.4) | 0.67 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 121 (28.6) | 73 (25.2) | 48 (36.4) | 0.02 |

| Depression | 131 (31.0) | 68 (23.4) | 63 (47.7) | <0.001 |

| Anxiety | 89 (21.0) | 51 (17.6) | 38 (28.8) | 0.009 |

| Tobacco cessation counseling† | 86 (31.2) | 72/189 (38.1) | 14/87 (16.1) | <0.001 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD or No. (%) unless otherwise specified.

Lung function date available on 202 participants.

276 current smokers.

There were no significant differences between groups regarding age, sex, race, body mass index, or smoking history (Table 1). Those readmitted had lower percent predicted FEV1 (44.9 ± 17.3% vs. 50.2 ± 19.4%; P = 0.05), a higher prevalence of GERD (36.4% vs. 25.2%; P = 0.02), and more frequent depression (47.7% vs. 23.4%; P < 0.001) and anxiety (28.8% vs. 17.6%; P = 0.009) (Table 1). Of those who were current smokers, patients readmitted had a significantly lower rate of tobacco cessation counseling (16.1% vs. 38.1%; P < 0.001) (Table 1). Mean sodium levels were higher in patients who were readmitted within 1 year. No baseline differences were observed in other comorbidities including coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, and diabetes mellitus.

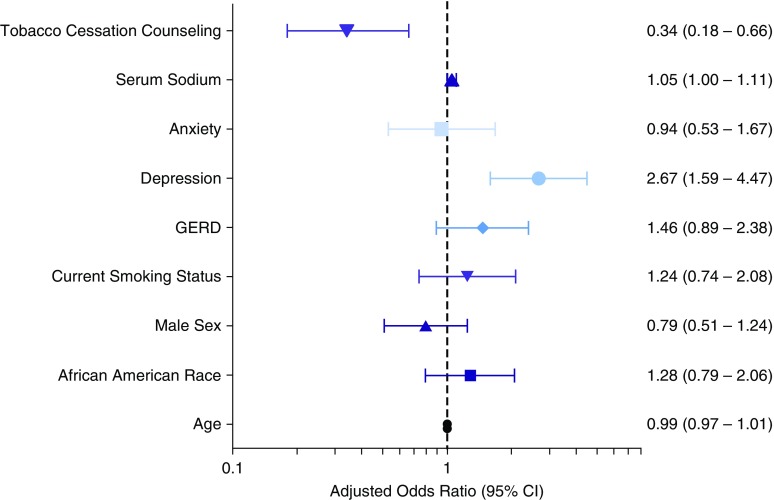

As seen in Table 2, depression (odds ratio [OR], 2.98; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.93–4.61; P < 0.001), anxiety (OR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.16–3.06; P = 0.010), and GERD (OR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.09–2.65; P = 0.019) were associated with increased risk of 1-year readmission on univariate analysis, whereas tobacco cessation counseling was associated with reduced 1-year readmission (unadjusted OR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.20–0.67; P = 0.001). After adjusting for variables significant on univariate analysis (GERD, anxiety, serum sodium, and tobacco cessation counseling) and other variables (age, race, sex, and current smoking status) that could potentially influence readmissions, depression remained significantly associated with increased risk of 1-year readmission (adjusted OR, 2.67; 95% CI, 1.59–4.47; P < 0.001), and tobacco cessation counseling was associated with reduced risk of 1-year readmission (adjusted OR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.18–0.66; P = 0.001) (Figure 1). FEV1 data were not available in all subjects; however, when FEV1 was entered into the multivariable model, depression was significantly associated with 1-year readmission (see Table E1 in the online supplement).

Table 2.

Predictors of readmission at 1 yr

| Variables | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | 0.520 |

| African American | 1.06 (0.69–1.64) | 0.783 |

| Male | 0.71 (0.47–1.08) | 0.107 |

| Current smoking | 0.99 (0.64–1.57) | 0.972 |

| GERD | 1.70 (1.09–2.65) | 0.019 |

| Depression | 2.98 (1.93–4.61) | <0.001 |

| Anxiety | 1.89 (1.16–3.06) | 0.010 |

| Serum sodium, mmol/L | 1.06 (1.01–1.12) | 0.029 |

| Tobacco cessation counseling | 0.37 (0.20–0.67) | 0.001 |

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; GERD = gastroesophageal reflux disease; OR = odds ratio.

Figure 1.

Independent predictors of readmission for acute exacerbation of COPD at 1 year. Variables shown are those significant on univariate comparisons between subjects with and without readmission within 1 year of index admission. The following variables were included in the multivariable model: age, race, sex, current smoking status, GERD, depression, anxiety, serum sodium, and tobacco cessation counseling. CI = confidence interval; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GERD = gastroesophageal reflux disease.

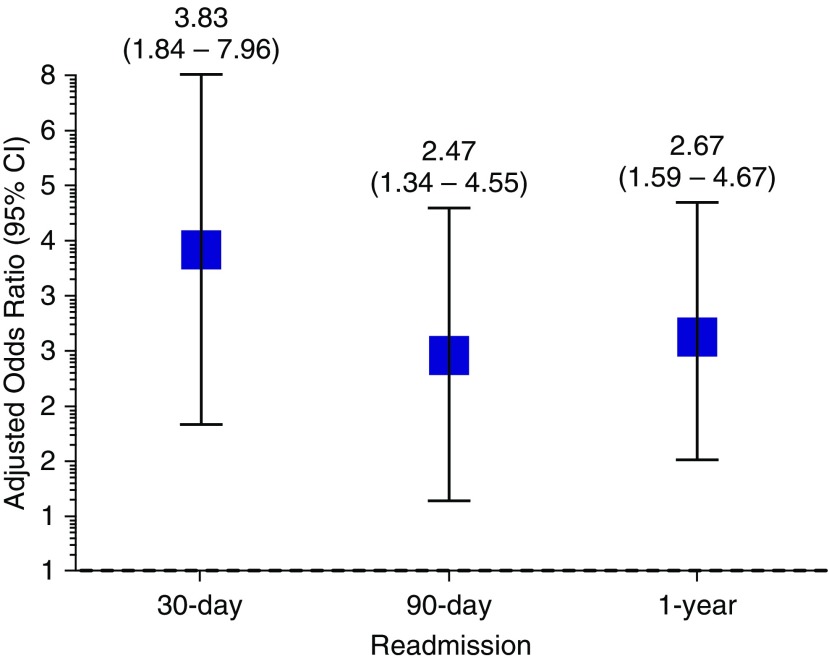

To investigate the role depression played in short-term readmission, we analyzed 30-day (Table E2) and 90-day readmission proportions by univariate and multivariable modeling. Forty-seven patients (11%) were readmitted within the first 30 days of index admission; 23 (5%) were readmitted between days 31 and 90, and 62 (15%) were readmitted between days 91 and 365 after index admission. The cumulative 1-year readmission rate was 31%. Depression was associated with increased 30-day readmission on univariate analysis (unadjusted OR, 4.31; 95% CI, 2.30–8.10; P < 0.001) and remained significant after multivariable adjustment for age, race, sex, smoking status, GERD, sodium level, anxiety, and tobacco cessation counseling (adjusted OR, 3.83; 95% CI, 1.84–7.96; P < 0.001) (Figure 2). After adjustment for these variables, depression was also independently associated with increased risk of 90-day readmission (adjusted OR, 2.47; 95% CI, 1.34–4.55; P = 0.004) (Figure 2). Anxiety was associated with increased risk of 30-day readmission on univariate analysis (unadjusted OR, 2.65; 95% CI, 1.39–5.04; P = 0.003) but did not achieve statistical significance after multivariable adjustment (adjusted OR, 1.44; 95% CI, 0.68–3.05; P = 0.342).

Figure 2.

Depression and risk of readmission for acute exacerbation of COPD at 30 days, 90 days, and 1 year. Black boxes represent adjusted odds ratio with bars representing the 95% CIs. The following variables were included in the multivariable model: age, race, sex, current smoking status, gastroesophageal reflux disease, depression, anxiety, serum sodium, and tobacco cessation counseling. CI = confidence interval; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Discussion

We found that depression is a risk factor for both short-term (30-d and 90-d) and 1-year readmission for acute exacerbation of COPD. Furthermore, we showed that tobacco cessation counseling was associated with reduced risk of 1-year readmission. Because both depression and smoking status are potentially modifiable, they may be valuable targets for interventions aimed at reducing COPD readmissions.

It is estimated that as many as 40% of patients with COPD have comorbid depression or suffer from depressive symptoms (29, 30), and we found a comparable prevalence in our population. However, the percentages in our study and in the general COPD population likely underestimate the actual prevalence of depression, partly because COPD and depression share a number of overlapping symptoms such as decreased energy and fatigue (31), and the effect of COPD symptoms or acute exacerbations of COPD on a patient’s psychological state is poorly understood (32). Importantly, although depression has been shown to be an independent risk factor for mortality in patients with COPD and is linked with an increased risk of exacerbations (27, 33–35), little is known about the association between depression and readmissions for acute exacerbation of COPD. As far as we know, our study is the first to show that depression is associated with an increased risk of both short- and long-term readmissions for acute exacerbation of COPD (36).

Patients with COPD and comorbid depression represent a potentially unique subgroup with difficult-to-control disease (32). Patients with COPD and depression report increased dyspnea, worse quality of life, and decreased treatment adherence, thus making it less likely that proven medical therapies or behavioral interventions such as tobacco cessation or pulmonary rehabilitation would be effective or their benefits maintained (37, 38). Although the underlying mechanistic links remain uncertain, the association between depression and COPD hospitalization is likely bidirectional, wherein depression worsens COPD-related morbidity and mortality, and COPD increases the risk of depression (39, 40).

Previous studies have linked psychological comorbidities with increased risk of mortality in patients with COPD, although data about readmissions are less definitive (38, 41). Coventry and colleagues prospectively examined psychosocial risk factors, including depressive symptoms and social support, and readmissions in a small cohort of patients with COPD in the United Kingdom and found a modest correlation with readmission risk in 1 year (26). Ng and colleagues also prospectively examined outcomes in patients with COPD and depressive symptoms, and although they found an increased risk of mortality and hospital stay, they did not find an increased risk of readmission (42). Xu and colleagues found an independent effect of depression on acute exacerbation of COPD risk but did not examine the risk of readmissions (27). We now report a robust association between depression and risk of readmission for acute exacerbation of COPD in a well-defined patient population, not only in the short term but also over a 1-year period, suggesting that depression is a sustained risk factor for readmission after an index hospitalization.

Although there are no prospective randomized studies of medical therapy for depression and readmission rates, retrospective studies suggest that antidepressant medication use is associated with a significantly lower mortality rate in this population (34). Furthermore, in one randomized clinical trial in patients with COPD and depression, a personalized outpatient intervention program composed of education and counseling improved not only depressive symptoms and adherence to antidepressants, but also dyspnea-related disability (43). Pulmonary rehabilitation can modify both depression symptoms and readmission rates (44, 45), but whether there is a causative link between reduction in depression scores and readmission rates has not been tested. In a retrospective analysis of Medicare data, Ahmedani and colleagues showed that patients with congestive heart failure, pneumonia, and acute myocardial infarction experienced increased risk of 30-day hospital readmission in the presence of comorbid depression (46). Given that reducing 30-day readmission for acute exacerbation of COPD is now a target set forth by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, these studies, together with our data, support the need for further research, including testing of pharmacologic and behavioral interventions, to examine psychological comorbidities such as depression as potentially modifiable risk factors for readmission for acute exacerbation of COPD. Anxiety has also been linked to a worse sensation of dyspnea in COPD (47) and increased risk of acute exacerbation of COPD (36, 47), but data on the risk of readmission are limited. Although we found an association between anxiety and readmissions on univariate analysis, this did not remain significant after multivariable modeling. Depression and anxiety frequently coexist, and depression appears to be a stronger risk factor for readmissions.

In our analysis, we also found that in-hospital tobacco cessation counseling reduced 1-year readmission rates, despite a low percentage (11.4%) of patients readmitted at 1 year who received tobacco cessation education. Persistent smoking is a known risk factor for acute exacerbation of COPD (48). Coultas and colleagues found a correlation between current smoking status and increased risk of depressive symptoms (49). Depression can also play a role in lack of adherence to tobacco cessation in patients with COPD (42). Although the creation of tobacco cessation groups in the stable outpatient setting has been shown to decrease hospitalizations, there is limited evidence regarding the effect of instituting in-hospital tobacco cessation interventions and their effect on readmission rates for acute exacerbation of COPD (48, 50). The mechanisms underlying the positive effects of tobacco cessation are likely related to airway remodeling and reduction in pulmonary inflammation (51). This represents an additional approach that should be tested prospectively.

Although hyponatremia has been shown in other retrospective studies to be a predictor of COPD hospitalization (52), perhaps reflecting the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone release, volume overload, and/or cor pulmonale, we found on univariate analysis that higher serum sodium was associated with readmission risk over 1 year. Although high sodium may reflect dehydration as often seen in COPD exacerbations, we did not find a relationship between readmission and hemoconcentration. Further studies are needed to prospectively assess the predictive value of serum sodium. We also found on univariate analysis that GERD was a predictor of readmissions at 1 year, a finding supported by recent studies (53, 54).

Limitations

This retrospective study was based on administrative data from a single center. However, we reviewed all charts and included only those patients confirmed by physicians to have met the standardized criteria for acute exacerbation of COPD. In addition, because data were not available on the severity of depression using depression scales, we used physician diagnosis and medication use as our diagnostic criteria for depression. This may have underestimated the prevalence of depression and not allowed for stratification on the basis of depressive symptoms or disease severity. However, our findings do suggest that it would be prudent for physicians to be vigilant in assessing their patients with COPD for comorbid depression. Regarding this, the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation recommends screening for depression at enrolment in rehabilitation programs (55). Furthermore, our findings of an association between depression and both short- and long-term readmissions for acute exacerbation of COPD should inform a randomized controlled trial to assess whether this is a truly modifiable risk factor.

We recognize that socioeconomic factors such as education and financial resources are important factors that could potentially modify readmission risk; however, we do not have reliable information on these variables. Comorbidities were defined on the basis of their presence in physician notes in the medical record, which reflects a combination of physician-confirmed and self-reported conditions, and inaccuracies in the latter could have biased our results.

We did not have lung function data for all patients, but our secondary sensitivity analyses for only those patients with FEV1 data showed that depression remained a strong predictor of readmissions. Although we were able to capture data accurately for readmissions to our center, we may have missed capturing data for readmissions to other hospitals. Finally, our study is subject to the usual limitations of retrospective design, including selection bias, misclassification bias, and residual confounding.

Conclusions

Depression is associated with both short- and long-term readmissions for acute exacerbation of COPD. Tobacco cessation counseling before hospital discharge also represents an important target that can potentially decrease 1-year readmission rates. Further studies are needed to assess the impact of interventions targeting depression and tobacco cessation counseling on the rate of readmissions for acute exacerbation of COPD.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: S.P.B. is the guarantor of the manuscript and is responsible for the work as a whole; A.S.I., S.P.B., and M.T.D. contributed to the study design; A.S.I., S.P.B., J.J.G., N.M.P., and J.C.W. contributed to the data collection; S.P.B., J.J.G., and M.T.D. contributed to the data analysis; A.S.I., S.P.B., and M.T.D. contributed to the writing of the manuscript; J.J.G., J.M.W., J.L.T., N.M.P., d.K., J.C.W., and M.T.D. contributed to the review of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Blanchette CM, Dalal AA, Mapel D. Changes in COPD demographics and costs over 20 years. J Med Econ. 2012;15:1176–1182. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2012.713880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halldin CN, Doney BC, Hnizdo E. Changes in prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma in the US population and associated risk factors. Chron Respir Dis. 2015;12:47–60. doi: 10.1177/1479972314562409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Groenewegen KH, Schols AM, Wouters EF. Mortality and mortality-related factors after hospitalization for acute exacerbation of COPD. Chest. 2003;124:459–467. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.2.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Makris D, Moschandreas J, Damianaki A, Ntaoukakis E, Siafakas NM, Milic Emili J, Tzanakis N. Exacerbations and lung function decline in COPD: new insights in current and ex-smokers. Respir Med. 2007;101:1305–1312. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt SA, Johansen MB, Olsen M, Xu X, Parker JM, Molfino NA, Lash TL, Sørensen HT, Christiansen CF. The impact of exacerbation frequency on mortality following acute exacerbations of COPD: a registry-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e006720. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Llor C, Molina J, Naberan K, Cots JM, Ros F, Miravitlles M EVOCA study group. Exacerbations worsen the quality of life of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in primary healthcare. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62:585–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao Z, Ong KC, Eng P, Tan WC, Ng TP. Frequent hospital readmissions for acute exacerbation of COPD and their associated factors. Respirology. 2006;11:188–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2006.00819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalal AA, Shah M, D’Souza AO, Rane P. Costs of COPD exacerbations in the emergency department and inpatient setting. Respir Med. 2011;105:454–460. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bollu V, Ernst FR, Karafilidis J, Rajagopalan K, Robinson SB, Braman SS. Hospital readmissions following initiation of nebulized arformoterol tartrate or nebulized short-acting beta-agonists among inpatients treated for COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2013;8:631–639. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S52557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Almagro P, Barreiro B, Ochoa de Echaguen A, Quintana S, Rodríguez Carballeira M, Heredia JL, Garau J. Risk factors for hospital readmission in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiration. 2006;73:311–317. doi: 10.1159/000088092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah T, Churpek MM, Coca Perraillon M, Konetzka RT. Understanding why patients with COPD get readmitted: a large national study to delineate the Medicare population for the readmissions penalty expansion. Chest. 2015;147:1219–1226. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Criner GJ, Bourbeau J, Diekemper RL, Ouellette DR, Goodridge D, Hernandez P, Curren K, Balter MS, Bhutani M, Camp PG, et al. Executive summary: prevention of acute exacerbation of COPD: American College of Chest Physicians and Canadian Thoracic Society Guideline. Chest. 2015;147:883–893. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farquhar M, Higginson IJ, Fagan P, Booth S. Results of a pilot investigation into a complex intervention for breathlessness in advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): brief report. Palliat Support Care. 2010;8:143–149. doi: 10.1017/S1478951509990897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fabbri LM, Luppi F, Beghé B, Rabe KF. Complex chronic comorbidities of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:204–212. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00114307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu Y, Feng L, Feng L, Nyunt MS, Yap KB, Ng TP. Systemic inflammation, depression and obstructive pulmonary function: a population-based study. Respir Res. 2013;14:53. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-14-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGhan R, Radcliff T, Fish R, Sutherland ER, Welsh C, Make B. Predictors of rehospitalization and death after a severe exacerbation of COPD. Chest. 2007;132:1748–1755. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-3018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baker CL, Zou KH, Su J. Risk assessment of readmissions following an initial COPD-related hospitalization. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2013;8:551–559. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S51507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen HQ, Rondinelli J, Harrington A, Desai S, Amy Liu IL, Lee JS, Gould MK. Functional status at discharge and 30-day readmission risk in COPD. Respir Med. 2015;109:238–246. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu SF, Lin KC, Chin CH, Chen YC, Chang HW, Wang CC, Lin MC. Factors influencing short-term re-admission and one-year mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respirology. 2007;12:560–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2007.01110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roberts CM, Stone RA, Lowe D, Pursey NA, Buckingham RJ. Co-morbidities and 90-day outcomes in hospitalized COPD exacerbations. COPD. 2011;8:354–361. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2011.600362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel AR, Kowlessar BS, Donaldson GC, Mackay AJ, Singh R, George SN, Garcha DS, Wedzicha JA, Hurst JR. Cardiovascular risk, myocardial injury, and exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:1091–1099. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201306-1170OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhatt SP, Dransfield MT. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cardiovascular disease. Transl Res. 2013;162:237–251. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fan VS, Ramsey SD, Giardino ND, Make BJ, Emery CF, Diaz PT, Benditt JO, Mosenifar Z, McKenna R, Jr, Curtis JL, et al. National Emphysema Treatment Trial (NETT) Research Group. Sex, depression, and risk of hospitalization and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:2345–2353. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.21.2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanania NA, Müllerova H, Locantore NW, Vestbo J, Watkins ML, Wouters EF, Rennard SI, Sharafkhaneh A Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) study investigators. Determinants of depression in the ECLIPSE chronic obstructive pulmonary disease cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:604–611. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201003-0472OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coventry PA, Gemmell I, Todd CJ. Psychosocial risk factors for hospital readmission in COPD patients on early discharge services: a cohort study. BMC Pulm Med. 2011;11:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-11-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu W, Collet JP, Shapiro S, Lin Y, Yang T, Platt RW, Wang C, Bourbeau J. Independent effect of depression and anxiety on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations and hospitalizations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:913–920. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200804-619OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wedzicha JA, Donaldson GC.Exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease Respir Care 2003481204–1213.[Discussion, p. 1213–1205.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panagioti M, Scott C, Blakemore A, Coventry PA. Overview of the prevalence, impact, and management of depression and anxiety in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:1289–1306. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S72073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yohannes AM, Alexopoulos GS. Pharmacological treatment of depression in older patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: impact on the course of the disease and health outcomes. Drugs Aging. 2014;31:483–492. doi: 10.1007/s40266-014-0186-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yohannes AM, Alexopoulos GS. Depression and anxiety in patients with COPD. Eur Respir Rev. 2014;23:345–349. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00007813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rebbapragada V, Hanania NA. Can we predict depression in COPD? COPD. 2007;4:3–4. doi: 10.1080/15412550601166550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jennings JH, Digiovine B, Obeid D, Frank C. The association between depressive symptoms and acute exacerbations of COPD. Lung. 2009;187:128–135. doi: 10.1007/s00408-009-9135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qian J, Simoni-Wastila L, Rattinger GB, Lehmann S, Langenberg P, Zuckerman IH, Terrin M. Associations of depression diagnosis and antidepressant treatment with mortality among young and disabled Medicare beneficiaries with COPD. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35:612–618. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quint JK, Baghai-Ravary R, Donaldson GC, Wedzicha JA. Relationship between depression and exacerbations in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:53–60. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00120107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pooler A, Beech R. Examining the relationship between anxiety and depression and exacerbations of COPD which result in hospital admission: a systematic review. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:315–330. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S53255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turan O, Yemez B, Itil O. The effects of anxiety and depression symptoms on treatment adherence in COPD patients. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2014;15:244–251. doi: 10.1017/S1463423613000169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borges-Santos E, Wada JT, da Silva CM, Silva RA, Stelmach R, Carvalho CR, Lunardi AC. Anxiety and depression are related to dyspnea and clinical control but not with thoracoabdominal mechanics in patients with COPD. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2015;210:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Janssen DJ, Müllerova H, Agusti A, Yates JC, Tal-Singer R, Rennard SI, Vestbo J, Wouters EF Eclipse Investigators. Persistent systemic inflammation and symptoms of depression among patients with COPD in the ECLIPSE cohort. Respir Med. 2014;108:1647–1654. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Atlantis E, Fahey P, Cochrane B, Smith S. Bidirectional associations between clinically relevant depression or anxiety and COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2013;144:766–777. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qian J, Simoni-Wastila L, Rattinger GB, Zuckerman IH, Lehmann S, Wei YJ, Stuart B. Association between depression and maintenance medication adherence among Medicare beneficiaries with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29:49–57. doi: 10.1002/gps.3968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ng TP, Niti M, Tan WC, Cao Z, Ong KC, Eng P. Depressive symptoms and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effect on mortality, hospital readmission, symptom burden, functional status, and quality of life. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:60–67. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alexopoulos GS, Kiosses DN, Sirey JA, Kanellopoulos D, Seirup JK, Novitch RS, Ghosh S, Banerjee S, Raue PJ. Untangling therapeutic ingredients of a personalized intervention for patients with depression and severe COPD. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22:1316–1324. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coventry PA, Bower P, Keyworth C, Kenning C, Knopp J, Garrett C, Hind D, Malpass A, Dickens C. The effect of complex interventions on depression and anxiety in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60532. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Puhan MA, Scharplatz M, Troosters T, Steurer J. Respiratory rehabilitation after acute exacerbation of COPD may reduce risk for readmission and mortality:- a systematic review. Respir Res. 2005;6:54. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahmedani BK, Solberg LI, Copeland LA, Fang-Hollingsworth Y, Stewart C, Hu J, Nerenz DR, Williams LK, Cassidy-Bushrow AE, Waxmonsky J, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity and 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, AMI, and pneumonia. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66:134–140. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laurin C, Moullec G, Bacon SL, Lavoie KL. Impact of anxiety and depression on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation risk. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:918–923. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201105-0939PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Au DH, Bryson CL, Chien JW, Sun H, Udris EM, Evans LE, Bradley KA. The effects of smoking cessation on the risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:457–463. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0907-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coultas DB, Edwards DW, Barnett B, Wludyka P. Predictors of depressive symptoms in patients with COPD and health impact. COPD. 2007;4:23–28. doi: 10.1080/15412550601169190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Borglykke A, Pisinger C, Jørgensen T, Ibsen H. The effectiveness of smoking cessation groups offered to hospitalised patients with symptoms of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) Clin Respir J. 2008;2:158–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-699X.2008.00055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mortaz E, Masjedi MR, Rahman I. Outcome of smoking cessation on airway remodeling and pulmonary inflammation in COPD patients. Tanaffos. 2011;10:7–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mohan A, Bhatt SP, Mohan C, Arora S, Luqman-Arafath TK, Guleria R. Derivation of a prognostic equation to predict in-hospital mortality and requirement of invasive mechanical ventilation in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2008;50:335–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takada K, Matsumoto S, Kojima E, Iwata S, Okachi S, Ninomiya K, Morioka H, Tanaka K, Enomoto Y. Prospective evaluation of the relationship between acute exacerbations of COPD and gastroesophageal reflux disease diagnosed by questionnaire. Respir Med. 2011;105:1531–1536. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martinez CH, Okajima Y, Murray S, Washko GR, Martinez FJ, Silverman EK, Lee JH, Regan EA, Crapo JD, Curtis JL, et al. COPDGene Investigators. Impact of self-reported gastroesophageal reflux disease in subjects from COPDGene cohort. Respir Res. 2014;15:62. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-15-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ries AL, Bauldoff GS, Carlin BW, Casaburi R, Emery CF, Mahler DA, Make B, Rochester CL, Zuwallack R, Herrerias C. Pulmonary rehabilitation: Joint ACCP/AACVPR evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2007;131:4S–42S. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]