Abstract

In the current drive to incorporate molecular markers into treatment-selection for precision medicine, there has been a significant and we believe ill-advised omission of the large and routinely used group of drugs whose mechanism of action is DNA damage.

Keywords: Precision medicine, DNA-damaging agents

Precision Medicine and Recent and Ongoing Clinical Trials Based on Molecular Markers

In the field of cancer therapeutics, the concept of precision medicine is based on the premise that treatment choices tailored to individual patients using personalized cancer genomic data may markedly improve outcomes [1]. Inherent in this concept is the recognition that molecular alterations occurring within a specific patient's cancer must take on increasing importance relative to, or in addition to considerations of the tissue of origin [1]. Success stories of targeting therapies towards molecular alterations include the development of tyrosine kinase inhibitors for subsets of chronic myelogenous leukemia, lung cancer and melanoma patients with tumors harboring translocated Bcr-Abl and mutated EGFR and BRAF, respectively.

In an attempt to broaden the applicability of this approach, multiple clinical trials have been designed based on molecularly relevant information. The hope is that these molecular alterations might prove predictive of tumor response to pharmacological intervention [1]. These trials attempt to identify and target molecular events, and may be broadly separated into two categories; “umbrella” trials that investigate targeted therapeutic strategies in a single tumor type, and “basket” trials that are predicated on the hypothesis that the presence of a molecular marker affects response to a targeted therapy independent of, or in addition to tumor histology. Selected trials, molecular alterations and targeted therapies are synopsized in Table 1. Biomarker-integrated Approaches of Targeted Therapy for Lung Cancer Elimination (BATTLEi) is an umbrella trial that enrolled patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Based on the presence of specific markers, selection was made between four kinase inhibitors, or the retinoid × receptor ligand bexarotene [2]. Although benefit was reported for KRAS mutant patients who received sorafenib, other marker-matched therapies did not meet endpoints. ALCHEMISTii, Lung-MAPiii, and I-SPY2iv are ongoing umbrella trials designed for early-stage lung adenocarcinoma, squamous NSCLC, and neoadjuvant breast cancer, respectively.

Table 1.

Precision oncology trials, their molecular markers and drugs1

| Trial synopsis | Genomic alterations tested |

Drugs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Design | Tumors included |

Treatment arms/ Patient number/ Trial Status |

Mutation/ Amplification / Deletion |

Protein Expression (IHC)2 |

Kinase inhibitors |

Hormonal agents |

Others |

| BATTLE3 | Randomized Phase II (umbrella) | NSCLC refractory to prior therapy | 4 255 Complete | EGFR, KRAS BRAF, CCND1 | VEGF, VEGFR2, RXRα, RXRβ, RXRγ, CCND1 | Vandetanib, Erlotinib, Sorafenib | None | Bexarotene4 |

| ALCHEMIST5 | Randomized Phase II (umbrella) | Adjuvant NSCLC | 2 8,300 Ongoing | EGFR, ALK | EGFR | Erlotinib, Citzotinib | None | None |

| Lung-MAP6 | Phase II / III (umbrella) | Squamous Lung cancer | 3 10,000 Ongoing | Sequencing of ~200 genes | Selected cases | Taselisib, Palbociclib, AZD4547 | None | Durvalumab7 |

| I-SPY28 | Phase II (umbrella) | Neoadjuvant breast cancer | 7 1,200 Ongoing | 70 gene array | ERBB2, ESR1, PGR | Neratinib, Trastuzumab | None | None |

| SHIVA9 | Randomized Phase II (basket) | Metastatic Solid tumors | 10 741 Complete | KIT, ABL1/2, RET, PI3KCA, AKT1,2,3, MEK, mTOR, RAPTOR, RICTOR, PTEN, STK11, INPP4B, BRAF, YES, FLT3, EGFR, ERBB2, SRC, EPHA2, LCK, PDGFRA/B | ESR1, PGR, AR | Erlotinib, Lapatinib, Sorafenib, Imatinib, Dasatinib, Vemurafenib, Everolimus | Abiraterone, Letrozole, Tamoxifen, Trastuzumab | None |

| CUSTOM10 | Pilot (basket) | Metastatic NSCLC, SCLC, thymic cancers | 5 647 Complete | EGFR, K,N,HRAS BRAF, PIK3CA, AKT, PTEN, ERBB2, KIT, PDGFRA | None | Erlotinib, Selumetibin, MK2206, Lapatinib, Sunitinib | None | None |

| NCI-MATCH11 | Phase II (basket) | Previously treated solid tumors, lymphomas, myelomas | 24 3,000 Ongoing | EGFR, ERBB2, MET, ALK, ROS1, BRAF, PIK3CA, PTEN, NF1, KIT, GNAQ/GNA11, SMO, PTCH1, FGFR1,2,3, DDR2, AKT1, NRAS, CCND1,2,3, Mismatch repair | None | Afatinib, AZD 4547, AZD 5363, AZD9291, Binimetinib, Crizotinib, Dabrafenib, Dasatinib, Defactinib, GSK2636771, Palbociclib, Sunitinib, Taselisib, Trametinib | None | Vismodegib12 Nivolumab13 T-DM114 |

Footnotes

Drugs which are invariant across study arms are not listed.

IHC is immunohistochemistry.

See Resources section i.

Bexarotene is a retinoic acid receptor ligand.

See Resources section ii.

See Resources section iii.

Durvalumab (MED14736) is an anti-PD-L1, a programmed cell death gene. A monoclonal antibody.

See Resources section IV.

See Resources section v.

See Resources section Vi.

See Resources section vii..

Vismodegib acts as a cyclopamine-competitive antagonist of the smoothened receptor (SMO).

Nivolumab is a humanized IgG4 anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody.

T-DM1 is ado-trastuzumab emtansine, a monoclonal antibody (trastuzumab) linked to a cytotoxic agent (emtansine or DM-1).

The SHIVAv and CUSTOMvi trials had limited success and design limitation that led to less than expected frequencies of molecular alterations in patients. The ongoing NCI-Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice Analysis for Therapy Choice (MATCHvii) trial is designed to examine the molecular features of 5,000 patients with solid tumors or lymphoma whose disease has progressed on standard therapy. Molecular markers are used independent of tumor histology to select one of 17 drugs, including 14 kinase inhibitors, an antibody-drug conjugate targeting a hormone receptor, an antagonist of the smoothened receptor, and an anti-PD-1 antibody [3]. This trial has 24 treatment arms, each with a drug treatment for one or more molecular abnormalities.

Lack of Inclusion of the Classical DNA-Targeting Drugs in Molecular Trials

Precision oncology trials to date have been remarkable for the fact that the overwhelming majority of drugs across study arms are protein kinase inhibitors (see Table 1). They are also remarkable for the minority of patients who express the molecular marker; for example, in an interim analysis of the 795 patients who enrolled in the NCI-MATCH trial, only 16 patients were able to enter and receive treatment on one of the treatment arms [4]. Considering the far less than expected frequency of the molecular events, we posit that application of more widely expressed molecular markers and expanding the therapies tested in these trials beyond kinase inhibitors could markedly enhance the scope and impact of the precision oncology trials.

DNA targeting drugs, such as cisplatin, etoposide, topotecan, and gemcitabine, the workhorses of cancer therapy, are not tested in the context of precision oncology trials except as constants across all arms. The reasons for this include increased risk and difficulty for both clinicians and institutions involved in publishing additional results on pre-existing drugs, and patent status and decreased profitability for the companies involved in their production.

As the promise of precision medicine rests on its ability to direct appropriate treatment to the patient group that might receive benefit, the largest pool to which to apply this logic are the pre-existing drugs. There is no reason to think that these established drugs should be any less appropriate than the newer drugs for a more directed application based on the molecular nature of a patient's specific disease. After all, each of these drugs has in its turn obtained FDA-approval due to demonstrable positive affects in some patient population. The level of success within clinical trials then as now, is based on the same factors, including: i) the importance of the target gene or pathway, ii) the effectiveness of the drug in affecting that target, and iii) the identification of the patient population to which it should be applied. It is that third parameter which now needs to be sharpened.

Prospective Approaches to the Inclusion of the DNA-targeting Drugs

Precision in the clinical application of DNA targeting drugs remains both promising and challenging. While the primary molecular targets and mechanisms-of-action of DNA-targeted therapies are well established: base adducts, crosslinks, topoisomerase cleavage complexes, nucleotide shortage, and poly(ADPribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) trapping, the usefulness of many currently available signatures, such as those from gene mutation, expression, methylation, and copy number profiles remains limited. This is due to drug responses being influenced by factors beyond their specific mechanisms of action, including their ability to reach and penetrate tumors, and cellular resistance mechanisms. Still, as patients in treatment today receive these drugs essentially without molecular-based stratification, development of a more directed approach should achieve significant gains in patient response while minimizing toxicity.

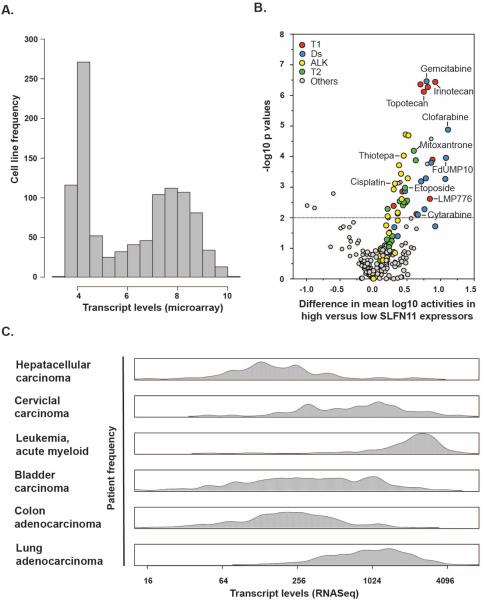

One promising predictive biomarker of sensitivity to DNA targeting agents emerging from cell line data is the expression of SLFN11. SLFN11 (from the word schlafen, which in German means sleeping) is a gene that has recently been causally linked with irreversible cell cycle arrest in response to a broad spectrum of DNA replication inhibitors [5]. High expression of SLFN11 is the significant correlate of response to DNA-damaging drugs including topoisomerase I and II inhibitors, alkylating agents, and DNA synthesis inhibitors (Ds) in multiple independent studies (Figure 1A and B) [5–7]. It also has variability of expression within patient samples (Figure 1C), and thus might be informative for significant portions of the patient population, both within and across tumor types [8]. These are two significant advantages over the infrequently occurring markers currently being employed as indicators for individual kinase inhibitors. Validated assays for detection of SLFN11 expression in patient tumors are needed for this marker to proceed in clinic.

Figure 1.

SLFN11 expression in cancer cells and tissues and its effect on drug activities for FDA-approved and clinical trial drugs. A. Histogram of SLFN11 transcript distribution in the 1036 Cancer Cell Line Encylopedia (CCLE) cancer cell lines [13]. The x-axis is the transcript log2 intensities. The y-axis is the frequency of the cell lines within that bin. B. Volcano plot of the effect of SLFN11 expression on the 108 FDA-approved and 70 clinical trial drug activities in the NCI-60 [14]. The x-axis is the difference in mean log10 growth inhibition 50% activities based on measurement by transcript levels as found between the higher SLFN11 expressers (>−0.3) and the lower (<−0.3) as defined in A. The y-axis is the −log10 p value as calculated by t test. The dashed horizontal line is at the p<0.01 level of significance. C. Density plots of patients SLFN11 transcript levels from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [8]. The x-axis is the transcript level fragments per kilobase per million reads (FPKM) as measured using RNASeq. The y-axis is the frequency of the cell lines within that kernal.

An already established marker that is not commonly used clinically is methylguanine methyltransferase (MGMT). MGMT removes the 06-methylguanine lesions generated by temozolomide. A relatively large number of cancers, especially glioblastoma, do not express MGMT, which renders them highly sensitive to temozolomide, unless they are also deficient in mismatch repair (especially involving MLH1, PMS2, MSH2, and MSH6) [9]. Hence, for temozolomide, both MGMT and mismatch repair status of the tumor should provide molecular insight for the likelihood of response.

Based on cancer cell lines genomic and drug response analyses [6, 7] there are additional emerging candidates to fulfill the role of marker. Genetic inactivation of DNA repair genes has been extended to homologous recombination deficiencies (HRD) in tumors (such as inactivation of BRCA1, BRCA2 or PALB2), which renders them hypersensitive to PARP inhibitors, cisplatin and topoisomerase I inhibitors [10, 11]. The challenge here is how to score tumors for HRD beyond large sequencing of the many genes that determine the HRD phenotype. Also to be considered as candidates are: i) SLX4 with Ds drugs (raltitrexed, cytarabine, and cyclocytidine), as well as topoisomerase I inhibitors (topotecan, irinotecan, and the indenoisoquinoline LMP776), ii) MUS81 with cladribine, and iii) RAD52 with ifosfamide [6, 12].

Concluding Remarks

Whereas the concept of precision medicine has permeated many diseases, oncology is at the forefront of such efforts as evidenced by the numerous clinical trials and ambitious investments in this field. Efforts are underway to overcome some of the challenges to this approach including the difficulties of identification of relevant molecular events and the less than expected frequency of such events in patients. Through the use of robust molecular indicators of pharmacological response such as BRAF mutational activation and perhaps SLFN11 gene expression, it is hoped that cancer might be converted into a disease that is more successfully managed. Identification of these robust molecular indicators, for the protein kinase inhibitors, DNA damaging agents, or any other drug type will be requisite for the success of the precision medicine concept. It is time we woke up to the underexplored promise of achieving more precise application of DNA-targeted drugs.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Resources

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00409968. The BATTLE PubMed identifier is 22586319.

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show?term=alchemist&rank=3. The ALCHEMIST PubMed identifiers are 26408304 and 25677079.

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02154490?term=swog+s1400&rank=1. The Lung-MAP PubMed identifier is 2154490.

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01042379. The I-SPY2 PubMed identifier is 27406346.

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01771458. The SHIVA PubMed identifier is 26342236.

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01306045. The CUSTOM PubMed identifier is 25667274.

http://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/clinical-trials/nci-supported/nci-match. The MATCH PubMed identifier is 2465060.

References

- 1.Yu KH, Snyder M. Omics profiling in precision oncology. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2016 doi: 10.1074/mcp.O116.059253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu S, Lee JJ. An overview of the design and conduct of the BATTLE trials. Chin Clin Oncol. 2015;4(3):33. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2304-3865.2015.06.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agarwal S, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-mediated cytotoxicity involves ADP-ribosylation. Journal of Immunology. 1988;140:4187–4192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NCI-sponsered trials in precision medicine. http://dctd.cancer.gov/MajorInitiatives/NCI-sponsored_trials_in_precision_medicine.htm - h02.

- 5.Zoppoli G, et al. Putative DNA/RNA helicase Schlafen-11 (SLFN11) sensitizes cancer cells to DNA-damaging agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(37):15030–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205943109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sousa FG, et al. Alterations of DNA repair genes in the NCI-60 cell lines and their predictive value for anticancer drug activity. DNA Repair (Amst) 2015;28:107–15. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rees MG, et al. Correlating chemical sensitivity and basal gene expression reveals mechanism of action. Nat Chem Biol. 2016;12(2):109–16. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga/dataAccessMatrix.htm.

- 9.Zhang J, et al. Temozolomide: mechanisms of action, repair and resistance. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2012;5(1):102–14. doi: 10.2174/1874467211205010102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson N, et al. Stabilization of mutant BRCA1 protein confers PARP inhibitor and platinum resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(42):17041–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305170110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Connor MJ. Targeting the DNA Damage Response in Cancer. Mol Cell. 2015;60(4):547–60. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reinhold WC, et al. Using CellMiner 1.6 for Systems Pharmacology and Genomic Analysis of the NCI-60. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(17):3841–52. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cancer Cell Line Encylopedia (CCLE) https://portals.broadinstitute.org/ccle/data/browseData?conversationPropagation=begin.

- 14.CellMiner http://discover.nci.nih.gov/cellminer.