Abstract

Rationale: In a prior study, lumacaftor/ivacaftor treatment (≤28 d) in patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) heterozygous for F508del-CFTR did not improve lung function.

Objectives: To evaluate an optimized lumacaftor/ivacaftor dosing regimen with a longer duration in a cohort of patients heterozygous for F508del-CFTR.

Methods: Patients aged 18 years or older with a confirmed CF diagnosis and percent predicted FEV1 (ppFEV1) of 40 to 90 were randomized to lumacaftor/ivacaftor (400 mg/250 mg every 12 h) or placebo daily for 56 days. Primary outcomes were change in ppFEV1 at Day 56 and safety. Other disease markers were evaluated.

Measurements and Main Results: Of 126 patients, 119 (94.4%) completed the study. Lumacaftor/ivacaftor was well tolerated, although chest tightness and dyspnea occurred more frequently with active treatment than with placebo (27.4% vs. 14.3% and 14.5% vs. 6.3%, respectively). Mean (SD) ppFEV1 values at baseline were 62.9 (14.3) in the active treatment group and 60.1 (14.0) in the placebo group. Absolute changes in ppFEV1 (least squares mean [SE]) at Day 56 were −0.6 (0.8) percentage points in the active treatment group and −1.2 (0.8) percentage points in the placebo group (P = 0.60). CF respiratory symptom scores in the active treatment group improved by a mean of 5.7 points versus a decrease of −0.8 in the placebo group (P < 0.01). No changes in body mass index occurred. Changes from baseline in sweat chloride (least squares mean [SE]) at Day 56 were −11.8 (1.3) mmol/L in the active treatment group and −0.8 (1.2) mmol/L in the placebo group (P < 0.0001).

Conclusions: Sweat chloride and respiratory symptom scores improved with lumacaftor/ivacaftor, though no meaningful benefit was seen in ppFEV1 or body mass index in patients heterozygous for F508del-CFTR.

Clinical trial registered with www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01225211).

Keywords: percent predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second, sweat chloride, adverse events

The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein is an ion channel in the apical membrane of epithelial cells that conducts chloride ions and helps regulate bicarbonate ion transport (1, 2). Cystic fibrosis (CF) is caused by defects in the CFTR protein arising from mutations in the CFTR gene (3). The F508del mutation is the most common cause of CF, present in 86.5% (4) of patients with CF in the United States and in about 73% of patients with CF worldwide, with approximately 38% of the global CF population being homozygous for the F508del-CFTR mutation (5). The F508del-CFTR mutation primarily causes defects in processing and trafficking of the CFTR protein; most F508del-CFTR is targeted for degradation before reaching the cell surface (6). Furthermore, the F508del-CFTR protein expressed at the cell surface exhibits defects in both function (gating) and stability (7). Absent or deficient CFTR protein results in severe epithelial dysfunction, leading to deleterious effects in the pancreas, gastrointestinal tract, reproductive tract, and respiratory system (8).

Lumacaftor is a CFTR corrector that increases the delivery of CFTR protein to the cell surface by improving the processing and trafficking of F508del-CFTR protein (9). Ivacaftor, a CFTR potentiator, increases the channel open probability (or gating) of both normal and mutant CFTR at the cell surface to enhance total ion (chloride) transport in vitro (10). When combined, the effects of lumacaftor/ivacaftor are significantly greater than either agent alone, as demonstrated in vitro and clinically (9, 11, 12).

In cohorts 1–3 of this phase II study (VX09-809-102), patients homozygous for F508del-CFTR showed improvements in percent predicted FEV1 (ppFEV1) when treated with lumacaftor 600 mg once daily or 400 mg every 12 hours in combination with ivacaftor 250 mg every 12 hours for 28 days, after a 28-day pretreatment period of lumacaftor monotherapy (11). Further, two large, nearly identical phase III studies demonstrated clinical efficacy when lumacaftor/ivacaftor was administered to patients homozygous for F508del-CFTR over a 24-week treatment period, as shown by improved lung function, reduced frequency of CF-related pulmonary exacerbations (PEx), and improved body mass index (BMI) (12).

Previously in the VX09-809-102 study, in patients with CF who were heterozygous for F508del-CFTR, lumacaftor/ivacaftor combination therapy did not improve lung function after the one regimen administered to them (lumacaftor 600 mg once daily/ivacaftor 250 mg every 12 h) (11). In this article, we report findings from cohort 4 of the same study, in which the effects of lumacaftor/ivacaftor combination therapy over a longer treatment period (56 d) and with an increased lumacaftor dose (400 mg every 12 h) were assessed in individuals heterozygous for the F508del-CFTR mutation. Some of the results of this study have been reported previously in the form of an abstract (13).

Methods

Study Design and Participants

Detailed methods describing this phase II multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled VX09-809-102 study (www.clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT01225211), as well as results from the first three cohorts, have been published previously (11). In cohort 4, patients were randomized at 51 sites in Australia, Belgium, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The study protocol, informed consent, and other necessary documents were approved by an independent ethics committee or institutional review board for each study site before initiation. This study was conducted in accordance with good clinical practice as described in the International Conference on Harmonization Guideline E6, Good Clinical Practice, Consolidated Guidance (April 1996).

A total of 126 patients aged 18 years or older with a confirmed diagnosis of CF and ppFEV1 between 40 and 90 (inclusive) of normal for age, sex, and height were eligible for inclusion in cohort 4 (14, 15). All patients were tested for CFTR genotype at screening; eligible patients had the F508del-CFTR mutation on one allele plus a second allele with a mutation predicted to result in the lack of CFTR production or otherwise expected to be unresponsive to ivacaftor (based on in vitro testing). Second CFTR allele mutations for these patients are given in Table E1 in the online supplement. All enrolled patients provided written informed consent.

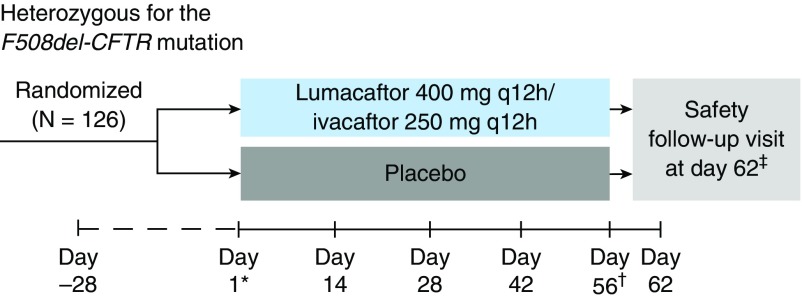

Patients were randomized 1:1 to receive either lumacaftor 400 mg every 12 hours in combination with ivacaftor 250 mg every 12 hours or matched placebo for 56 days (Figure 1). Randomization was stratified by sex (male vs. female) and ppFEV1 severity at screening (<70 vs. ≥70).

Figure 1.

Study design. *The first dose of study drug was administered on Day 1. †On Day 56, the last dose of study drug was administered in the morning. ‡Patients who prematurely discontinued study drug treatment 7 or more days before the Day 56 visit were not required to complete a safety follow-up visit. q12h = every 12 hours.

Procedures

Lumacaftor 400 mg every 12 hours/ivacaftor 250 mg every 12 hours or placebo were administered orally on Day 1 through Day 56. Spirometric assessments and sweat chloride collection were completed, and the Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire–Revised (CFQ-R) (16) was administered prior to the morning dose of study drug at applicable study visits.

Outcomes

The primary outcome measures were safety, tolerability, and the absolute change from baseline in ppFEV1 at Day 56. Key secondary outcome measures included relative change from baseline in ppFEV1 and absolute change in BMI, patient-reported respiratory symptoms in the CFQ-R respiratory domain (a change of 4 points in the respiratory domain score being considered the minimal clinically important difference) (16), body weight, and sweat chloride concentrations at Day 56. Safety evaluations included laboratory assessments, clinical evaluation of vital signs, pulse oximetry, physical examinations, electrocardiograms, and standard adverse event reporting.

Statistical Analyses

Efficacy analyses were conducted for all patients who were randomized and received at least one dose of study drug. The primary efficacy outcome measure was analyzed using a mixed model for repeated measures analysis, with absolute change from baseline in ppFEV1 as the dependent variable; treatment, visit, and treatment-by-visit interaction as fixed effects; and patient as a random effect. The model was adjusted for sex and for ppFEV1 at screening (<70 vs. ≥ 70).

The primary result obtained from the model was treatment effect at Day 56. Key secondary outcomes were analyzed using a mixed model for repeated measures analysis similar to that used for the primary outcome measure. A hierarchical testing procedure was used to control the overall type I error rate at 0.05 for the primary endpoint and the key secondary endpoints in the following order: absolute change in ppFEV1, relative change in ppFEV1, absolute change in BMI, absolute change in the CFQ-R respiratory domain, and absolute change in body weight, all from baseline at Day 56. At each step, the test for treatment effect was considered statistically significant if the P value was less than or equal to 0.05 and all previous tests also met this level of significance.

Results

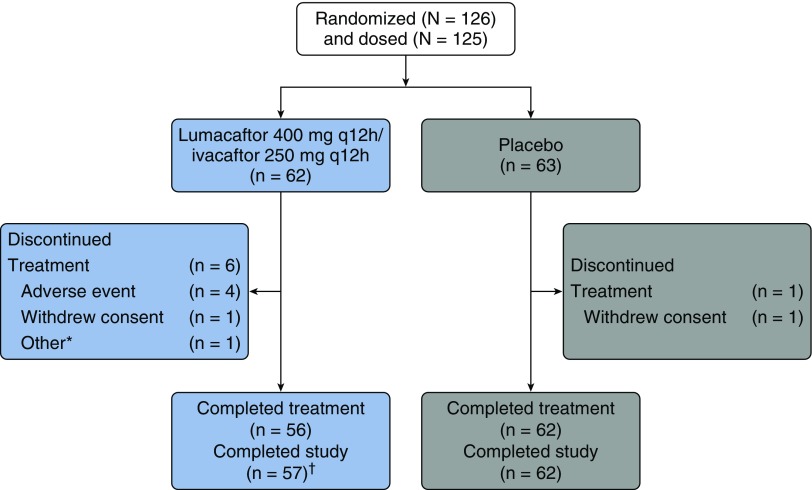

Patient disposition is shown in Figure 2. Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics were similar across treatment groups and consistent with those seen in patients with CF and moderate lung disease (Table 1) (17). The mean (SD) age of all participants was 29.9 (8.4) years. The mean (SD) baseline ppFEV1 values were 62.9 (14.3) in the lumacaftor/ivacaftor treatment group and 60.1% (14.0) in the placebo group; these values are similar to those in other large studies of this treatment combination (11, 12). The mean (SD) sweat chloride values at the time of randomization were 100.7 (12.5) mmol/L in the lumacaftor/ivacaftor treatment group and 102.9 (9.2) mmol/L in the placebo group, reflecting minimal CFTR function at baseline.

Figure 2.

Patient disposition. *Did not meet inclusion criterion of F508del-CFTR mutation on one allele. †One patient discontinued treatment prior to Day 56 but completed required Day 56 visit off study treatment. q12h = every 12 hours.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | Lumacaftor 400 mg Every 12 h/Ivacaftor 250 mg Every 12 h (n = 62) | Placebo (n = 63) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr, mean (SD) | 29.0 (7.8) | 30.8 (8.9) |

| Range, yr | 18–53 | 19–58 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 29 (46.8) | 31 (49.2) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 22.8 (3.2) | 22.2 (3.0) |

| ppFEV1 at baseline, mean (SD) | 62.9 (14.3) | 60.1 (14.0) |

| <40,* n (%) | 2 (3.2) | 4 (6.3) |

| ≥40 to <70, n (%) | 40 (64.5) | 41 (65.1) |

| ≥70 to ≤90, n (%) | 19 (30.6) | 18 (28.6) |

| >90,* n (%) | 1 (1.6) | 0 |

| Sweat chloride concentration, mmol/L, mean (SD); n | 100.7 (12.5); 61 | 102.9 (9.2); 63 |

Definition of abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; ppFEV1 = percent predicted FEV1.

ppFEV1 enrollment criterion (FEV1 40 to 90% of predicted normal value) was applied at screening.

The most common adverse events (Table 2) were respiration abnormal (i.e., chest tightness), infective PEx of CF, cough, increased sputum, and dyspnea. The overall incidence of adverse events was similar in the lumacaftor/ivacaftor group and the placebo group, although more patients in the treatment group than in the placebo group experienced abnormal respiration and dyspnea (17 [27.4%] and 9 [14.5%] patients in the lumacaftor/ivacaftor group vs. 9 [14.3%] and 4 [6.3%] patients in the placebo group, respectively). Drug treatment was well tolerated; only four (6.5%) patients in the lumacaftor/ivacaftor group had adverse events leading to discontinuation in the study (Figure 2). Two patients discontinued because of infective PEx of CF; one discontinued because of increased aspartate transaminase and alanine transaminase; and one discontinued because of abnormal respiration, nausea, and dizziness. None of the patients in the placebo group discontinued the study because of adverse events. Most adverse events were mild or moderate in severity. Serious adverse events were reported in nine (14.5%) patients in the lumacaftor/ivacaftor treatment group and five (7.9%) in the placebo group.

Table 2.

Adverse events reported by at least 10% of patients in either treatment group

| MedDRA Preferred Term, n (%) | Lumacaftor 400 mg Every 12 h/Ivacaftor 250 mg Every 12 h (n = 62) | Placebo (n = 63) |

|---|---|---|

| Any adverse event | 52 (83.9) | 53 (84.1) |

| Respiration abnormal* | 17 (27.4) | 9 (14.3) |

| Infective PEx of CF | 14 (22.6) | 12 (19.0) |

| Cough | 13 (21.0) | 12 (19.0) |

| Sputum increased | 10 (16.1) | 12 (19.0) |

| Dyspnea | 9 (14.5) | 4 (6.3) |

| Nausea | 7 (11.3) | 7 (11.1) |

| Pyrexia | 7 (11.3) | 9 (14.3) |

| Diarrhea | 7 (11.3) | 5 (7.9) |

| Hemoptysis | 5 (8.1) | 8 (12.7) |

| Abdominal pain, upper | 5 (8.1) | 7 (11.1) |

| Headache | 3 (4.8) | 11 (17.5) |

Definition of abbreviations: CF = cystic fibrosis; MedDRA = Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (version 17.0); PEx = pulmonary exacerbations.

Generally reported as chest tightness.

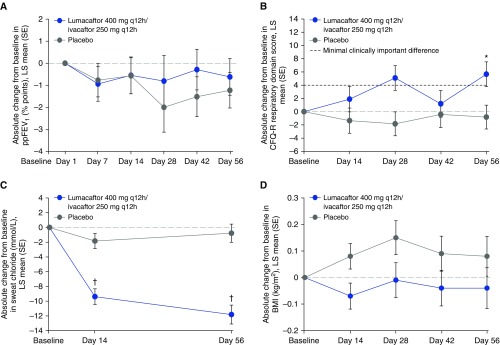

The key efficacy data are shown in Table 3. Patients were assessed at baseline and Day 56. The absolute changes in ppFEV1 (least squares [LS] mean [SE]) at 56 days were −0.6 (0.8) percentage points for patients in the lumacaftor/ivacaftor treatment group and −1.2 (0.8) percentage points for patients in the placebo group (P = 0.60) (Figure 3A). The LS mean (95% confidence interval [CI]) difference (active − placebo) was 0.6 (−1.7, 2.9). The number of patients who had at least a 5% improvement in ppFEV1 at the end of the study was no greater in the lumacaftor/ivacaftor treatment group (odds ratio, 1.7; 95% CI = 0.7, 4.3; nominal P = 0.25). Note that, within the framework of the hierarchical testing procedures, statistically significant differences between treatment groups were not observed for the primary endpoint; therefore, none of the key secondary endpoints could be considered statistically significant, regardless of the nominal P value. The patient-reported CFQ-R respiratory domain scores (LS mean [SE]) were 5.7 (1.9) points in the lumacaftor/ivacaftor treatment group and −0.8 (1.8) points for the placebo group; the treatment difference was 6.5 points, which was nominally statistically significant (P = 0.01) (Figure 3B and Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of key efficacy data

| Lumacaftor 400 mg Every 12 h/Ivacaftor 250 mg Every 12 h (n = 62) | Placebo (n = 63) | |

|---|---|---|

| ppFEV1 absolute change

(percentage points) from baseline at Day 56* | ||

| Number of subjects | 55 | 60 |

| LS mean (SE) | −0.6 (0.8) | −1.2 (0.8) |

| LS mean difference (active − placebo), 95% CI | 0.6 (−1.7, 2.9) | — |

| P value vs. placebo | 0.60 | — |

| ppFEV1 relative change (%)

from baseline at Day 56* | ||

| Number of subjects | 55 | 60 |

| LS mean (SE) | −0.7 (1.4) | −2.2 (1.4) |

| LS mean difference (active − placebo), 95% CI | 1.5 (−2.4, 5.4) | — |

| P value vs. placebo | 0.44 | — |

| BMI (kg/m2) absolute change

from baseline at Day 56* | ||

| Number of subjects | 56 | 60 |

| LS mean (SE) | −0.04 (0.08) | 0.08 (0.08) |

| LS mean difference (active − placebo), 95% CI | −0.1 (−0.3, 0.1) | — |

| P value vs. placebo | 0.26 | — |

| CFQ-R respiratory domain score

absolute change from baseline at Day 56* | ||

| Number of subjects | 55 | 60 |

| LS mean (SE) | 5.7 (1.9) | −0.8 (1.8) |

| LS mean difference (active − placebo), 95% CI | 6.5 (1.4, 11.6) | — |

| P value vs. placebo | 0.01 | — |

| Body weight (kg) absolute change from

baseline at Day 56* | ||

| Number of subjects | 56 | 60 |

| LS mean (SE) | −0.1 (0.2) | 0.2 (0.2) |

| LS mean difference (active − placebo), 95% CI | −0.3 (−0.9, 0.3) | — |

| P value vs. placebo | 0.37 | — |

| Sweat chloride: absolute change

(mmol/L) from baseline at Day 56 | ||

| Number of subjects | 54 | 59 |

| LS mean (SE) | −11.8 (1.3) | −0.8 (1.2) |

| LS mean difference (active − placebo), 95% CI | −11.0 (−14.5, −7.6) | — |

| P value vs. placebo | <0.0001 | — |

| ppFEV1 responders

(≥5%) relative change from baseline at Day

56 | ||

| Yes, n (%) | 14 (22.6) | 9 (14.3) |

| No, n (%) | 48 (77.4) | 54 (85.7) |

| OR (95% CI) vs. placebo | 1.7 (0.7, 4.3) | — |

| P value vs. placebo | 0.25 | — |

Definition of abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; CFQ-R = Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire–Revised; CI = confidence interval; LS = least squares; OR = odds ratio; ppFEV1 = percent predicted FEV1.

These outcome measures were included in the hierarchical testing procedure and appear in the table in the order in which they were tested.

Figure 3.

Absolute change from baseline in (A) ppFEV1 by visit, (B) CFQ-R respiratory domain score by visit, (C) sweat chloride concentration by visit, and (D) body mass index by visit. *P = 0.01 versus placebo; †P < 0.0001 versus placebo. BMI = body mass index; CFQ-R = Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire–Revised; LS = least squares; ppFEV1 = percent predicted FEV1; q12h = every 12 hours; lumacaftor/ivacaftor (n = 62), placebo (n = 63).

CFTR activity was estimated by serial assessments of sweat chloride (Figure 3C and Table 3). A reduction in sweat chloride was observed in the lumacaftor/ivacaftor group (LS mean [SE]) at Day 14 (−9.4 [1.1] mmol/L; nominal P < 0.0001), which became further pronounced at Day 56 (−11.8 [1.3] mmol/L; nominal P < 0.0001). Patients in the placebo group had no significant change in sweat chloride at any time point (−1.8 [1.0] and −0.8 [1.2] mmol/L at Day 14 and Day 56, respectively). Nutritional status was estimated by the change in BMI. There were no statistically significant improvements in BMI (Figure 3D and Table 3) or body weight (Table 3) during the study, and outcomes favored the placebo group.

Discussion

The purpose of this cohort of study VX09-809-102 was to determine whether prolonged treatment with combination lumacaftor/ivacaftor therapy at a dose higher than previously tested could result in clinically meaningful efficacy improvements in patients heterozygous for the F508del-CFTR mutation, with a second allele with a mutation predicted to result in the lack of CFTR production or otherwise expected to be unresponsive to ivacaftor. Results for cohorts 1–3 had suggested the potential for efficacy, based on a gene–dose effect with lumacaftor/ivacaftor combination therapy for an abbreviated (28-d) treatment period (11). Results from this cohort (cohort 4) suggest that the combination of lumacaftor 400 mg every 12 hours/ivacaftor 250 mg every 12 hours over a 56-day treatment period does not significantly improve ppFEV1, the primary outcome measure, in patients heterozygous for F508del-CFTR.

Despite observing negative results for this primary outcome measure, results of secondary outcomes from this study suggest that corrector-potentiator treatment has a pharmacologic effect in patients with a single F508del allele. Nominally significant improvements (P < 0.0001) were observed in sweat chloride concentrations, a biomarker for CFTR activity in patients with CF. The magnitude of the difference in sweat chloride between treatment groups at 56 days (11.0 mmol/L [95% CI = −14.5, −7.6]) was similar to that seen with the same dosing regimen when administered to patients homozygous for F508del-CFTR (11.1 mmol/L [95% CI = −18.5, −3.7]), although the point estimate for the latter was based on a small sample size (n = 9) (11).

Ongoing studies evaluating the effects of lumacaftor/ivacaftor on sweat chloride, or alternatively other F508del-CFTR corrector-potentiator combination treatments, may provide additional context for these data because this degree of CFTR function improvement would be expected to result in at least a modest clinical benefit over the duration studied in this trial. Indeed, the data provide a lower limit of aggregate sweat chloride change, indicating that changes of less than 10 mmol/L are unlikely to have measurable clinical benefit in modulator studies of up to 2 months in duration. Such information is valuable for the advancement of sweat chloride as a potential surrogate outcome measure when developing future clinical trials.

In addition to changes in sweat chloride, lumacaftor/ivacaftor treatment was also associated with improvements in CF symptoms. The absolute change from baseline at Day 56 in the CFQ-R respiratory domain score with lumacaftor/ivacaftor treatment was 5.7 points, compared with −0.8 points with placebo (treatment difference, 6.5 [95% CI = 1.4, 11.6]). The lumacaftor/ivacaftor response exceeded the minimally clinically important difference (4 points) and was higher than the score observed with the same dosing regimen in patients homozygous for F508del-CFTR (CFQ-R score, 4.0 [95% CI = −6.8, 14.8]) (11). These findings are somewhat surprising, given the magnitude of changes in other clinical indicators, and might indicate that patients are perceiving a treatment effect that is not measured by lung function.

It should be noted that no benefits were seen in BMI with lumacaftor/ivacaftor therapy in this study. There was a small improvement in BMI in patients receiving placebo at Day 56, although the change was not statistically significant compared with the lumacaftor/ivacaftor group.

Lumacaftor/ivacaftor was well tolerated in this population, and the safety profile was consistent with that observed in the phase III studies of lumacaftor/ivacaftor in patients homozygous for F508del-CFTR (12). Few treatment discontinuations occurred, and no differences in the overall rate of adverse events were seen in the lumacaftor/ivacaftor treatment group as compared with the placebo group. However, chest tightness and dyspnea were observed more frequently in the lumacaftor/ivacaftor treatment group than in the placebo group; similar findings have been reported for patients homozygous for F508del-CFTR (11, 12). These respiratory symptoms tended to occur upon treatment initiation in patients in the lumacaftor/ivacaftor treatment group, whereas patients receiving placebo generally experienced symptoms after the first week of the study. In those patients continuing lumacaftor/ivacaftor, the effect resolved with continued dosing by the fourth week for the lumacaftor/ivacaftor group and by the sixth week for the placebo group.

It is possible that subclinical bronchoconstriction partly accounts for the inconsistency in CFTR activity as reflected in sweat chloride, clinical symptoms, and change in lung function at Day 56. The evaluation of other correctors that are similarly efficacious but not associated with chest tightness may help provide context for these data. These findings further suggest that developers of CFTR-targeted strategies may need to consider outcomes beyond ppFEV1 to guide development, such as patient-reported outcomes and acute PEx frequency.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that lumacaftor/ivacaftor is generally well tolerated in patients heterozygous for F508del-CFTR but does not exhibit sufficient efficacy to warrant further evaluation when the primary outcome measure is ppFEV1. Nevertheless, significant changes in sweat chloride concentrations in the lumacaftor/ivacaftor group versus placebo, coupled with an improvement in patient-reported respiratory symptoms, indicate some restitution of CFTR function.

Additional material

Supplementary data supplied by authors.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

Editorial support was provided by Stephen Parker, ELS, and Dhrupad Patel, Pharm.D. D.P. is an employee of Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated and may own stock or stock options in that company. S.P. is a former employee of Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated and may own stock or stock options in that company. Medical writing and editorial support were provided by Edwin Thrower, Ph.D., and Dena McWain. E.T. and D.M. are employees of Ashfield Healthcare Communications, which received funding from Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated.

Footnotes

Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated provided funding for this study and for editorial support in manuscript development. Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated was involved in study design as well as data collection, analysis, and interpretation, and reviewed and provided feedback on the manuscript. The authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The authors had editorial control of the manuscript and provided their final approval of all content.

Author Contributions: S.M.R., M.W.K., D.W., and M.P.B.: had the idea for and designed the study; S.M.R., S.A.M., E.R., S.C.B., M.W.K., and M.P.B.: collected, analyzed, and interpreted data; X.L., G.M., and D.W.: analyzed and interpreted data; and S.M.R., S.A.M., E.R., S.C.B., M.W.K., D.W., and M.P.B.: wrote and revised the manuscript.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Berger HA, Anderson MP, Gregory RJ, Thompson S, Howard PW, Maurer RA, Mulligan R, Smith AE, Welsh MJ. Identification and regulation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator-generated chloride channel. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:1422–1431. doi: 10.1172/JCI115450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi JY, Muallem D, Kiselyov K, Lee MG, Thomas PJ, Muallem S. Aberrant CFTR-dependent HCO3− transport in mutations associated with cystic fibrosis. Nature. 2001;410:94–97. doi: 10.1038/35065099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Derichs N. Targeting a genetic defect: cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator modulators in cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir Rev. 2013;22:58–65. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00008412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient registry: annual data report 2014 Bethesda, MD: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation; 2014[accessed 2016 May 19]. Available from: https://www.cff.org/2014-Annual-Data-Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clinical and Functional Translation of CFTR (CFTR2) Summary for F508del mutation Baltimore: CFTR2 Team; 2016[accessed 2016 May 19]. Available from: http://www.cftr2.org/mutation.php?view=general&mutation_id=1 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lukacs GL, Mohamed A, Kartner N, Chang XB, Riordan JR, Grinstein S. Conformational maturation of CFTR but not its mutant counterpart (ΔF508) occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum and requires ATP. EMBO J. 1994;13:6076–6086. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06954.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Goor F, Straley KS, Cao D, González J, Hadida S, Hazlewood A, Joubran J, Knapp T, Makings LR, Miller M, et al. Rescue of ΔF508-CFTR trafficking and gating in human cystic fibrosis airway primary cultures by small molecules. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:L1117–L1130. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00169.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Sullivan BP, Freedman SD. Cystic fibrosis. Lancet. 2009;373:1891–1904. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60327-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Goor F, Hadida S, Grootenhuis PD, Burton B, Stack JH, Straley KS, Decker CJ, Miller M, McCartney J, Olson ER, et al. Correction of the F508del-CFTR protein processing defect in vitro by the investigational drug VX-809. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:18843–18848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105787108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Goor F, Hadida S, Grootenhuis PD, Burton B, Cao D, Neuberger T, Turnbull A, Singh A, Joubran J, Hazlewood A, et al. Rescue of CF airway epithelial cell function in vitro by a CFTR potentiator, VX-770. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:18825–18830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904709106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyle MP, Bell SC, Konstan MW, McColley SA, Rowe SM, Rietschel E, Huang X, Waltz D, Patel NR, Rodman D VX09-809-102 study group. A CFTR corrector (lumacaftor) and a CFTR potentiator (ivacaftor) for treatment of patients with cystic fibrosis who have a phe508del CFTR mutation: a phase 2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:527–538. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wainwright CE, Elborn JS, Ramsey BW, Marigowda G, Huang X, Cipolli M, Colombo C, Davies JC, De Boeck K, Flume PA, et al. TRAFFIC Study Group; TRANSPORT Study Group. Lumacaftor–ivacaftor in patients with cystic fibrosis homozygous for Phe508del CFTR. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:220–231. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rowe SM, McColley SA, Rietschel E, Li X, Bell SC, Konstan MW, Marigowda G, Waltz D, Boyle MP. Effect of 8 weeks of lumacaftor in combination with ivacaftor in patients with CF and heterozygous for the F508del‐CFTR mutation [abstract 254] Pediatr Pulmonol. 2014;49(Suppl 38):306. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:179–187. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang X, Dockery DW, Wypij D, Fay ME, Ferris BG., Jr Pulmonary function between 6 and 18 years of age. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1993;15:75–88. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950150204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quittner AL, Modi AC, Wainwright C, Otto K, Kirihara J, Montgomery AB. Determination of the minimal clinically important difference scores for the Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire-Revised respiratory symptom scale in two populations of patients with cystic fibrosis and chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa airway infection. Chest. 2009;135:1610–1618. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rowe SM, Heltshe SL, Gonska T, Donaldson SH, Borowitz D, Gelfond D, Sagel SD, Khan U, Mayer-Hamblett N, Van Dalfsen JM, et al. GOAL Investigators of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics Development Network. Clinical mechanism of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator potentiator ivacaftor in G551D-mediated cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:175–184. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201404-0703OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.