Abstract

An analysis of stomatal behavior reveals the importance of modeling slow stomatal responses and the impacts on photosynthesis under dynamic light environments.

Stomata control gaseous exchange between the leaf and bulk atmosphere, limiting CO2 uptake for photosynthesis and water loss by transpiration, and therefore determine plant productivity and water use efficiency. In order to function efficiently, stomata must respond to internal and external signals to balance these two diffusional processes. However, stomatal responses are an order of magnitude slower than photosynthetic responses, which lead to a disconnection between stomatal conductance and net CO2 assimilation. Here, we discuss the influence of anatomical features on the rapidity of stomatal movement and explore the temporal relationship between net CO2 assimilation and stomatal conductance responses. We describe how these mechanisms have been included into recent modeling efforts, increasing the accuracy and predictive power under dynamic environmental conditions, such as those experienced in the field.

Stomatal anatomical characteristics and behavior control gaseous fluxes between the internal leaf environment and the external atmosphere, with major implications for photosynthesis, plant water status, evaporative cooling, and nutrient uptake. The capacity of stomata to allow CO2 into the leaf or lose water is known as stomatal conductance (gs), measured as mole of flux per unit of area (mol m−2 s−1). Stomatal conductance is the reciprocal of stomatal resistance and is determined primarily by stomatal density, distribution, and pore area. Global water usage is predicted to double before 2030 (UNESCO, 2009) due to the rising global population, increasing the need for greater crop yields but with reductions in the amount of water available for their growth. This, along with more erratic precipitation episodes, is putting increasing pressure on breeders and scientists to find new crop varieties or breeding targets that would result in sustained or increased crop yields with less inputs of water. Most crop species are not indigenous to where they are currently cultivated and often are not fully adapted to the environmental conditions, potentially increasing the level of stress that the plant experiences. For decades, breeders focused mainly on selecting varieties for increased yield, decreasing the diversity of other traits of interest (e.g. stomatal behavior) and potential targets for selection. As stomata are key to plant photosynthesis and water use, this makes them attractive targets for manipulation to improve carbon uptake, optimize water use, and reduce drought stress. Earlier work used stable carbon isotopic discrimination as a proxy for time-integrated water use efficiency (WUE) and revealed that higher gs in wheat (Triticum aestivum) resulted in a lower level of limitation of net CO2 assimilation (A) and higher yield (Fischer et al., 1998). For this reason, previous research explored improving gas exchange via specific manipulation of steady-state gs (e.g. by manipulating stomatal density), while we have taken a less obvious approach and are exploring the rapidity of stomatal responses that synchronize gs with mesophyll demands for CO2 (Lawson et al., 2010; Lawson and Blatt, 2014; Raven, 2014) to improve A, WUE, and leaf temperature.

Stomata balance CO2 uptake and water loss by adjusting the pore aperture to changing environmental and internal cues. In general, stomata of C3 and C4 plants open with increasing or high light, low [CO2], and low vapor pressure deficit (VPD), while closure is driven by the reverse, low light, high [CO2], and high VPD (Raschke, 1975; Outlaw, 2003). However, it should be kept in mind that these environmental stimuli are rarely experienced by the plant in isolation; therefore, stomata must respond to multiple signals in a hierarchical manner (Lawson and Morison, 2004; Lawson et al., 2010; Aasamaa and Sõber, 2011). Although gs is closely linked with mesophyll demands for CO2 (Wong et al., 1979; Farquhar and Sharkey, 1982; Mansfield et al., 1990; Buckley and Mott, 2013), stomatal responses to changing conditions can be an order of magnitude and more slower than photosynthetic responses. Reports of correlations between A and gs often refer to steady-state measurements or long-term observations that do not reflect the reality of field conditions, as short-term fluctuations in environmental conditions can lead to a temporal disconnection between A and gs (Kirschbaum and Pearcy, 1988; Tinoco-Ojanguren and Pearcy, 1993; Lawson and Weyers, 1999; Lawson et al., 2010; McAusland et al., 2016). The lack of temporal synchronicity between A and gs under natural fluctuating light conditions has important implications for photosynthetic carbon gain and for the ratio of CO2 gained through photosynthesis to water lost by transpiration, known as WUE, as well as resulting in heterogeneity in gas exchange over individual leaves (Lawson and Weyers, 1999; McAusland et al., 2013) and within canopies (Weyers and Lawson, 1997). In this review, we will explore the temporal relationship between A and gs responses, the impact on WUE, and the influence of anatomical characteristics on stomatal responses. Although we recognize the impact of environmental variables such as [CO2], relative humidity, and soil water content on the temporal response of gs, here we will only focus on changes in light intensity. As part of describing temporal responses in gs, we will explore the use of models to better describe and allow a comparison of responses between different species. Many current and early models calculate gs in steady state, and although they are useful as a predictive tool to assess the role of gs on gaseous fluxes at the local and regional scale, they fail to incorporate the temporal (and spatial) heterogeneity in gs observed in the natural environment due to ever-changing environmental conditions.

IMPACT OF THE TEMPORAL RESPONSE OF gs ON PHOTOSYNTHESIS

Temporal Response of gs

Due to technical considerations, most studies regarding stomatal behavior on intact leaves have used gs as a proxy to investigate stomatal movements instead of directly measuring pore area. Despite this being a useful tool for understanding stomatal dynamics, it should be kept in mind that the relationship between gs and pore area is not linear, as the influence of pore area on gs decreases rapidly with the magnitude of stomatal opening (Kaiser and Kappen, 2001). Nevertheless, Kaiser and Kappen (1997, 2000, 2001) showed that gs and pore area measurements, although on different scales, generally lead to the same conclusion regarding limitations of photosynthesis (A) and water loss. It is well known that a low gs or slow stomatal opening can restrict the uptake of CO2 and, therefore, A (Farquhar and Sharkey, 1982; Barradas et al., 1994; Barradas and Jones, 1996; McAusland et al., 2016), while high gs facilitates higher rates of A but inevitably at the cost of greater water loss through transpiration (Barradas et al., 1994; Naumburg and Ellsworth, 2000; Lebaudy et al., 2008; Lawson et al., 2010; McAusland et al., 2013, 2016; Lawson and Blatt, 2014). In response to fluctuations in environmental parameters, it is commonly assumed that plants try to synchronize stomatal opening with the mesophyll demand for CO2 and stomatal closure with the need to minimize water loss through transpiration (Cowan and Farquhar, 1977; Farquhar et al., 1980; Mott, 2009; Lawson et al., 2012; Drake et al., 2013; Jones, 2013). However, slow gs kinetics (McAusland et al., 2016) means that the stomatal aperture lags behind the steady-state target (Kaiser and Kappen, 2000).

Light is the greatest environmental driver of photosynthesis, and stomatal response to light is one of the most well-researched stomatal behaviors (Shimazaki et al., 2007). Numerous studies have investigated steady-state stomatal responses to light; however, as these responses are measured under constant conditions, they represent situations that are rarely found in nature (Jones, 2013). Measurements of gs collected under field conditions are highly variable and, therefore, correlate poorly with those measured under steady-state conditions in the laboratory (Poorter et al., 2016), usually due to slow gs kinetics (McAusland et al., 2016), meaning that, when measured, stomata have not yet reached the new steady-state target (Whitehead and Teskey, 1995; Kaiser and Kappen, 2000; Lawson et al., 2010).

Stomatal Response to Dynamic Light

Several studies have investigated the dynamics of stomatal response and photosynthesis to fluctuations in environmental variables, especially light (Knapp and Smith, 1987; Kirschbaum et al., 1988; Tinoco-Ojanguren and Pearcy, 1993; Barradas et al., 1994; Lawson et al., 2010; Wong et al., 2012; McAusland et al., 2016). However, the majority of these have concentrated on the influence of sun and shade flecks on carbon gain in understory forest dwelling species (Chazdon, 1988; Chazdon and Pearcy, 1991; Tinoco-Ojanguren and Pearcy, 1993; Pearcy, 1994; Leakey et al., 2005) and for plants that have developmentally acclimated to shaded or exposed conditions (Knapp and Smith 1987, 1988), often ignoring dynamic stomatal response and the potential limitation on carbon gain or water loss. Over the diurnal period, these fluctuations in light (sun/shade flecks) drive the temporal and spatial dynamics of carbon gain and water loss (Lawson and Blatt, 2014). It is often the speed of the stomatal response to environmental fluctuations that is critical when assessing carbon uptake and WUE (Raschke, 1975; Kirschbaum and Pearcy, 1988; Lawson and Morison, 2004; Lawson et al., 2010). In the field, the response of A and gs is largely dominated by fluctuations in photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD; Pearcy, 1990; Way and Pearcy, 2012), which can vary on a scale of seconds, minutes, days, and even seasons (Assmann and Wang, 2001), and is driven by sun angle, cloud cover, and shading from overlapping leaves (Pearcy, 1990; Chazdon and Pearcy, 1991; Way and Pearcy, 2012); as a consequence, leaves are subjected to varying spectral qualities and light intensities. It is noteworthy that such rapid changes in PPFD will result in rapid intense modifications to leaf temperature, with greater gs providing enhanced evaporative cooling and possible protection against heat damage (Schymanski et al., 2013).

In the 1980s to early 1990s, Pearcy and colleagues investigated the impacts of sun flecks, primarily on carbon gain and later on stomatal dynamics. They dissected the temporal photosynthetic and gs response into different phases to explain the periods of response associated with limitations in A and overshoots of gs leading to excess water loss. The initial phase was termed the induction and represents periods of up to 10 min during which biochemical processes rather than CO2 supply limit carbon assimilation (Barradas and Jones, 1996). The second phase, dominated by stomatal limitation, describes slow gs responses that constrain CO2 diffusion and A (Lawson et al., 2010, 2012; Vialet-Chabrand et al., 2013; McAusland et al., 2016). The third phase explains the period in which gs remains high, exceeding the amount of gs required for maximum rates of carbon assimilation (Kirschbaum et al., 1988; Tinoco-Ojanguren and Pearcy, 1993; Lawson et al., 2010), leading to excess water loss (relative to carbon gained) and effectively a drop in WUE (McAusland et al., 2016). Studies mainly on forest understory species have reported that sun flecks may contribute 10% to 60% of the total daily carbon gain (Way and Pearcy, 2012), depending on forest type and plant age. Stomatal limitations on A have been estimated at up to 30%, with significant implications for carbon sequestration and crop yields (Fischer et al., 1998; Lawson and Blatt, 2014). Indeed, Kirschbaum et al. (1988) found that, if initial gs values were high, A could be 6 times higher 1 min after an increase in PPFD than if initial gs was low, an 82% gs limitation on A, illustrating the importance of gs in natural dynamic conditions such as those found in the field. Continued increases in gs after A has reached light saturation also have been reported, which led to a decrease in intrinsic water use efficiency (Wi) with higher water loss for no CO2 gain (Kirschbaum et al., 1988; Tinoco-Ojanguren and Pearcy, 1993; Lawson et al., 2010).

Differences in the speed of stomatal opening and closing and the magnitude of change in gs in response to sun and shade flecks are known to exist between species and within individual plants (Assmann and Grantz, 1990; Ooba and Takahashi, 2003; Franks and Farquhar, 2007; Vico et al., 2011; Drake et al., 2013; Vialet‐Chabrand et al., 2013). Response times also are dependent upon the plant water status (Lawson and Blatt, 2014), leaf age (Urban et al., 2008), the history of stress (Pearcy and Way, 2012; Porcar-Castell and Palmroth, 2012; Wong et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012), and the duration and magnitude of changes in PPFD (Weyers and Lawson, 1997; Lawson et al., 1998, 2012; Lawson and Blatt, 2014). There is also evidence to suggest that changes in growth environment during stomatal development influence the speed of response in mature leaves (Arve et al., 2017). The speeds of opening and closing in response to changing PPFD in many species are not correlated (Ooba and Takahashi, 2003); however, Vico et al. (2011) compared 60 published gas-exchange data sets on stomatal response to PPFD to determine the impact of stomatal delays on photosynthesis and found a general parallel relationship in the rates of stomatal response, concluding that rates of stomatal opening were essentially correlated with the rate of closure. If we assumed that there is no delay in stomatal opening or closing, optimal leaf gas exchange would be achievable (Cowan and Farquhar, 1977; Lawson and Blatt, 2014), but it is important to consider the fact that specific delays in stomatal movement may be indicators of the current needs of the plant (Ooba and Takahashi, 2003; Manzoni et al., 2011; Vico et al., 2011; Drake et al., 2013). The response of gs is thought to reflect this priority: under well-watered conditions in the canopy, stomata will remain open (particularly lower down in the canopy where VPD will be lower) in order to utilize light energy from sunflecks to maximize CO2 diffusion into the leaf (Lawson et al., 2012; Way and Pearcy 2012), even at the cost of further water loss (Allen and Pearcy, 2000), while under drought or water-limited conditions, stomata will often close to conserve water at the expense of carbon gain (Knapp and Smith, 1988).

Influence of Anatomy on Stomatal Response

Stomatal anatomical features such as stomatal density and size are known to determine steady-state gs (Franks and Farquhar, 2001) and are key components for determining the maximum theoretical gs of the plant (Dow et al., 2014). Stomatal size and density vary greatly between plant species and are influenced by the growth environment (Willmer and Fricker, 1996; Hetherington and Woodward, 2003; Franks and Beerling, 2009). Stomatal density often has been negatively correlated with stomatal size (Hetherington and Woodward, 2003; Franks and Beerling, 2009). Recently, a great deal of consideration has been given to the impact of stomatal anatomical features on stomatal function and gas exchange, particularly to the morphological and mechanical diversity of stomata with reference to performance and plasticity (Franks and Farquhar, 2007). Recent studies and reviews have implied that stomatal response times to environmental perturbations are affected by physical attributes such as size and density (Drake et al., 2013; Raven, 2014), the presence or absence of subsidiary cells (Franks and Farquhar, 2001), as well as the shape of the guard cells (McAusland et al., 2016) and their clustering (Papanatsiou et al., 2016) and that manipulation of these features could have positive effects for carbon gain and WUE (Doheny-Adams et al., 2012; Lawson et al., 2012; Tanaka et al., 2013; Franks et al., 2015).

Hetherington and Woodward (2003) first suggested that dumbbell-shaped stomata could open and close faster than kidney-shaped stomata in response to environmental perturbations, as even small changes in volume in the smaller dumbbell-shaped guard cells would lead to greater stomatal opening compared with the larger kidney-shaped guard cells. Franks and Farquhar (2007) took this further by advocating other factors that may influence the speed of response, such as guard cell geometry, mechanical advantage, osmotic or turgor pressure, and the energetic cost of guard cell movements (as mentioned previously). A mechanical advantage of dumbbell-shaped stomata was suggested to be associated with the reciprocal coupling of guard and subsidiary cell osmotic and turgor pressures, leading to more rapid stomatal movements (Franks and Farquhar, 2007; Raven, 2014). These findings underlie the potential of dumbbell-shaped stomata to track changes in environmental conditions and maximize the efficiency of photosynthesis and water use through increased stomatal response times (Hetherington and Woodward, 2003; McAusland et al., 2016), a point also highlighted by Chen et al. (2017) in their analysis of stomatal evolution. Drake et al. (2013) investigated the correlation between stomatal anatomy, specifically density and size, and stomatal opening speeds and found that the maximum rate of stomatal opening was driven by size and density. Although the work of Drake et al. (2013) and the review from Raven (2014) made significant progress in linking stomatal size to function, including the speed of response to light and associated implications, the size of stomata is not the only and main determinant of the speed of response. For example, Papanatsiou et al. (2016) note that stomatal clustering can affect gs kinetics independent of stomatal dimensions and the available pool of osmotic solutes available to drive aperture changes. The results of Drake et al. (2013) also could have been skewed by the experimental condition, as step changes in light from a state of darkness not only incur biochemical limitations on stomatal movement and assimilation but represent a state that is rarely seen in the natural environment except prior to dawn.

Recent work from Kaiser et al. (2016) using similar experimental conditions could have overestimated the biochemical limitation and underestimated the diffusional limitation on A due to the slow response of gs from dark. Producing a step change from low to high light is more representative of the conditions experienced in the field during a diurnal period from passing clouds and overlapping leaves (McAusland et al., 2016; Vialet-Chabrand et al., 2017); therefore, more relevant information can be gained regarding the speed of stomatal response and the implications this may have for carbon assimilation and WUE. In a recent study, McAusland et al. (2016) compared the speed of stomatal responses to a step change in light, in both dumbbell- and ellipse-shaped guard cells in a range of species, including model species and crops. These authors found that guard cell shape (dumbbell or elliptical) and potentially photosynthetic type (C3/C4) played a key role in determining the speed of stomatal response, with dumbbell-shaped guard cells exhibiting faster responses than those with elliptical guard cells. Slow stomatal opening in response to increasing light was demonstrated to limit carbon assimilation by approximately 10%, which would equate to substantial losses in carbon gain over the course of the day, potentially negatively impacting productivity and yield, whereas slow stomatal closure when PPFD decreased resulted in a significant decrease in WUE, as overshoots in gs by up to 80% were observed with only a negligible 5% gain in A. Closer coupling of A and gs, therefore, has the potential to enhance carbon gain and Wi and, in turn, improve performance, productivity, and yield (Lawson et al., 2010; Lawson and Blatt, 2014; Li et al., 2016; McAusland et al., 2016; Qu et al., 2016).

MODELING THE TEMPORAL RESPONSE OF STOMATA

As mentioned above dynamic stomatal behavior plays a key role in regulating the flux of carbon and water through the soil-plant-atmosphere continuum and is an important determinant for scaling leaf-level measurements of WUE and photosynthesis to the canopy level (Weyers et al., 1997). Modeling is generally considered the most effective tool for simulating stomatal responses to environmental conditions (Damour et al., 2010), and the importance of integrating stomatal behavior into scaling models is recognized (Weyers et al., 1997; Bernacchi et al., 2007; Lawson et al., 2010; Barman et al., 2014; Bonan et al., 2014; De Kauwe et al., 2015). Many current models calculate steady-state gs and have become successful tools for predicting the impact of gs on water and carbon fluxes at ecosystem and regional scales. However, heterogeneity in the spatial and temporal responses of stomata often is overlooked (Weyers et al., 1997; Lawson and Weyers, 1999), limiting the confidence with which these current models can predict larger scale responses or the impact of predicted climate change (Buckley et al., 2003; Dewar et al., 2009; Baldocchi, 2014). The addition of stomatal dynamics to existing models has the potential to reveal the extent to which gs has been inaccurately predicted by steady-state models. As stomata respond continuously to fluxes in environmental conditions and, therefore, gs is rarely in steady state, this reinforces the need for improved mechanistic models of gs (Damour et al., 2010; Vialet-Chabrand et al., 2016). Greater focus in future modeling efforts attempting to scale from the leaf to the canopy level should be given to the inclusion and integration of temporal stomatal dynamics to fluctuations in environmental signals (Vico et al., 2011; Vialet-Chabrand et al., 2013) to predict the impact of large-scale heterogeneity in stomatal traits on water and CO2 fluxes through the canopy, ecosystem, and global scales. Furthermore, as stomata are exposed to constant fluctuations over the diurnal period, it is often the speed of the stomatal response that is critical in determining CO2 uptake and transpiration dynamics over the course of the day (McAusland et al., 2016; Vialet-Chabrand et al., 2016) rather than the steady-state values that are often the basis of many existing models. Here, we will review the existing dynamic models and the advantages and disadvantages of their use and predictive power while also discussing the incorporation of dynamic models for greater accuracy in predicting stomatal impacts on A, gs, and Wi in a natural environment.

Modeling the Temporal Response of gs to Changes in Light Intensity

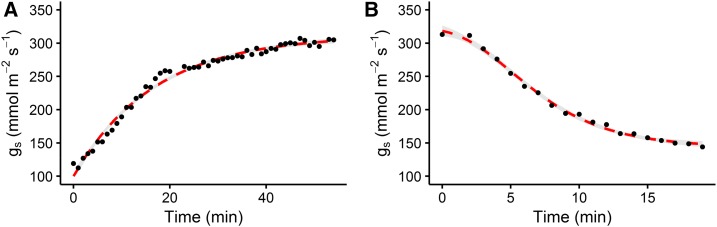

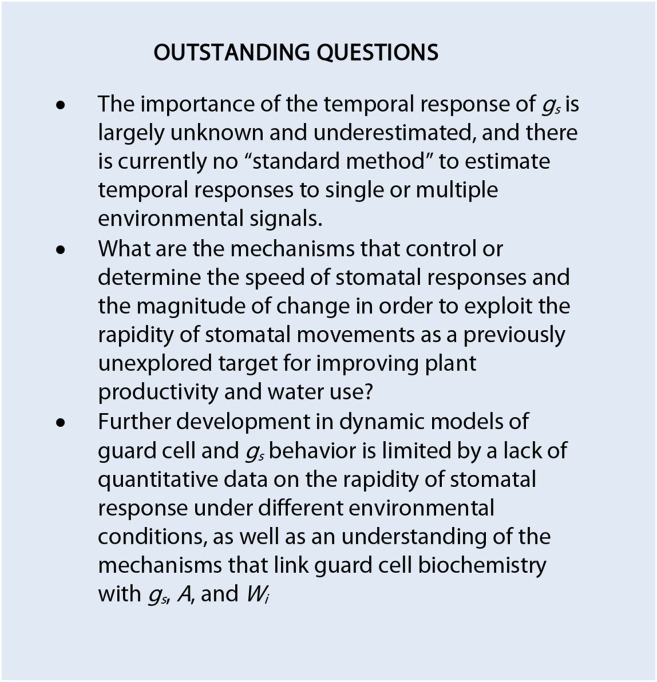

In the early 1970s, temporal responses of gs were examined to determine the degree of limitation on A and the regulation of water loss (Woods and Turner, 1971; Davies and Kozlowski, 1974; Horie, 1978). Most of these early studies were based on step increases and decreases in light intensity, revealing a slow exponential or sigmoidal variation in gs with time (Fig. 1). The response of gs to a step change in light intensity was initially evaluated as the time for gs to reach the new steady state (Gs) at the new light level or a percentage of this value as an estimator of the rapidity of response (Woods and Turner, 1971; Davies and Kozlowski, 1974; Grantz and Zeiger, 1986; Dumont et al., 2013). More recently, the rapidity of response has been estimated using a regression fit to the linear part of the gs response, providing an estimate of the maximum rate of gs increase (Tinoco-Ojanguren and Pearcy, 1992; Fay and Knapp, 1995; Naumburg et al., 2001; Drake et al., 2013). Temporal responses of gs assessed using these approaches are prone to errors, as they are largely dependent on the estimation of Gs that may never be reached and the linearity of the initial part of the curve. The lack of a standard method to estimate the temporal response of gs, (e.g. in the choice of the linear part of the curve) prevents a direct comparison of results from different studies. A more robust approach is to use normalized observations of gs between the initial and final Gs (Laffray et al., 1982; Iino et al., 1985; Barradas et al., 1994; Mencuccini et al., 2000; Drake et al., 2013). This approach not only provides a visual representation of the differences in temporal gs responses but also is independent of the magnitude of the gs response, although it is unable to summarize the overall response in one descriptive statistic. Moreover, if a steady state is not reached during the measurement period, it is difficult to normalize data.

Figure 1.

Application of an exponential model (A) and a sigmoidal model (B; red dashed lines) on the temporal response of gs (black dots) in Arabidopsis (Columbia-0 [Col-0]) to a step change in light intensity (from 100 to 1,000 µmol m−2 s−1 and from 1,000 to 100 µmol m−2 s−1, respectively). Gas-exchange measurements of gs were recorded at 60-s intervals; leaf temperature was maintained at 25°C, and leaf VPD was maintained at 1 kPa.

Dynamic Models of gs

An alternative to these earlier error-prone approaches is to fit a model to the temporal response of gs following a step change in light intensity and determine a set of parameter values to describe and enable an evaluation of specific parts of the response curve. In general, such models require the following parameters: an initial and final value of gs and a time constant. These parameters are targets, which means that if Gs is not reached during the response, the model can constrain the parameter value based on the shape of the response curve. Parameter values can be adjusted using a statistical method that provides the best set of values based on the comparison of the observations and the model outputs.

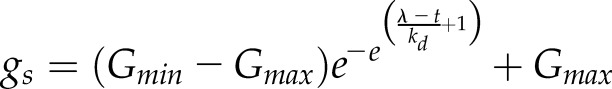

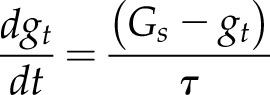

Typically, two empirical models based on the shape of the variation of gs are commonly used, an exponential and a sigmoidal model. For both models, a set of differential equations and associated analytical solutions are available. To date, a large number of studies have used the analytical equations of the exponential response of gs (Horie, 1978; Knapp, 1993; Whitehead and Teskey, 1995; Naumburg and Ellsworth, 2000; Franks and Farquhar, 2001, 2007; Naumburg et al., 2001; Vico et al., 2011; Martins et al., 2016; Qu et al., 2016) that can be formulated for an increase (Eq. 1) or decrease (Eq. 2) in gs:

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

where Gmin and Gmax represent the minimum and maximum steady state gs, τi and τd represent the time constants for the increase and decrease in gs, and t is the time at which gs is estimated starting from time 0. In this model, the time constants represent the time required to reach 63% of the total variation (when  ,

, ). The large number of studies using the exponential model is due to its ease of use and the fact that most of the observed temporal responses of gs have an exponential shape.

). The large number of studies using the exponential model is due to its ease of use and the fact that most of the observed temporal responses of gs have an exponential shape.

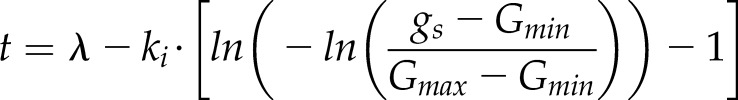

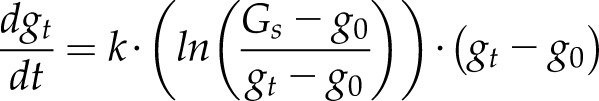

A delay in the increase in gs responses after a step increase in light has been reported for several species (Barradas et al., 1994; Naumburg and Ellsworth, 2000; Drake et al., 2013; Elliott-Kingston et al., 2016; McAusland et al., 2016), and the shape of this type of response can be described by a sigmoidal equation:

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

where ki and kd represent the time constants for the increase (Eq. 3) or decrease (Eq. 4) of gs and λ is the initial lag time. Time constants ki and kd do not directly represent a time to reach a percentage of Gs but also depend on λ. However, the time to reach any value of gs can be calculated by solving the previous equation as a function of time:

|

(5) |

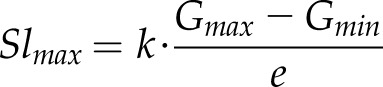

Using Equation 5, the equivalence between the exponential and sigmoidal time constants can be written as:

|

(6) |

where τ represents the time to reach 63% of the total gs variation including the initial lag time.

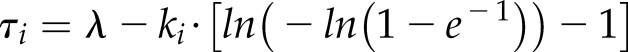

Another interesting property that has been used in numerous studies to describe the speed of stomatal response is the maximum slope of gs increase, which is calculated based on the previously described parameters:

|

(7) |

Equation 7 relates the effect on gs of stomatal density (approximated by G) and the speed of response of stomata (estimated by k), highlighting the importance of differences in stomatal density when drawing conclusions from differences in Slmax. It should be kept in mind that, as mentioned previously, the scaling up from stoma to leaf level is not a linear process, and caution should be taken when interpreting the temporal response of gs in terms of stomatal behavior (Kaiser and Kappen, 2001; Vialet-Chabrand et al., 2016).

Both the exponential (Fig. 1A) and sigmoidal (Fig. 1B) models can be fitted on data collected using a generic protocol that consists of a step increase in light intensity from 100 to 1,000 µmol m−2 s−1 while other environmental variables are held constant (e.g. relative humidity). This generic protocol has been used in numerous publications and can be adapted depending on the species. Although a step change in light intensity often is used as the standard method to assess temporal responses in gs, this approach is not fully representative of natural environmental variation but is close to what a plant may experience during a sunfleck in the field. We provide a curve-fitting routine in Microsoft Excel to illustrate the use of the exponential and sigmodal models described above in an accessible format (Supplemental File S1). Despite differences in timing or light intensities, the parameters derived from this protocol can be compared to characterize the differences in the temporal response of gs. Under a continuously changing light environment, the analytical models presented above can be biased, as they assume a constant Gs between each calculated time point. In the case of a dynamic light environment, differential equations would be preferred for their accurate and continuous descriptions of the gs response. A differential equation describing an exponential response of gs has been described previously (Horie, 1978; Noe and Giersch, 2004; Vico et al., 2011) but requires a larger number of steps to be solved and, therefore, has rarely been used (Kirschbaum et al., 1988; Noe and Giersch, 2004; Vialet-Chabrand et al., 2016):

|

(8) |

Alternatively, a differential equation for a sigmoidal variation of gs can be used (Vialet-Chabrand et al., 2013; Moualeu-Ngangue et al., 2016), providing a control on the initial lag experienced by stomata after a change in light intensity:

|

(9) |

Alternative, more complex equations than Equation 8 have been proposed by Kirschbaum et al. (1988), but they can be more difficult to parameterize due to their large number of parameters. The use of a differential equation required the calculation of the steady-state target Gs at any point of time, so Vialet-Chabrand et al. (2013) proposed the use of a spline function to estimate the light intensity (or any environmental variable) continuously and then use of these values to predict Gs using any already available steady-state model. Therefore, this approach to model the temporal response of gs can be used in existing steady-state gs models to predict the transient states of gs resulting from the previous variations in light intensity.

In many studies, the temporal response of gs has been associated with stomatal behavior and focused on the rapidity of stomatal movements (Franks and Farquhar, 2007; Drake et al., 2013; Raven, 2014). However, it is important to note that the rapidity of stomatal movements is not necessarily correlated to the rapidity of the variations of gs (Vialet-Chabrand et al., 2016). For example, a higher stomatal density can result in a higher rate of gs increase (Slmax) without changes in stomatal behavior (McAusland et al., 2016). Both anatomical traits (e.g. stomatal density and size) and biochemical traits (e.g. number and regulation of ion channels) describing stomatal behavior need to be considered to fully understand the kinetics of gs responses following a change in light intensity or any other environmental parameter. To this extent, empirical analysis of gs also may be extracted from mechanistic models of guard cells, notably OnGuard, which yields outputs in stomatal aperture that connect directly to the underlying processes of solute transport and metabolism (Chen et al., 2012; Hills et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012). Indeed, Wang et al. (2014) have used this platform to undertake a study of stomatal kinetics, incorporating a first-order sensitivity analysis of the dependence on individual ion channels and pumps at the plasma membrane and tonoplast. Their study yielded a number of unexpected results, as noted below.

An Example of Dynamic Modeling of gs

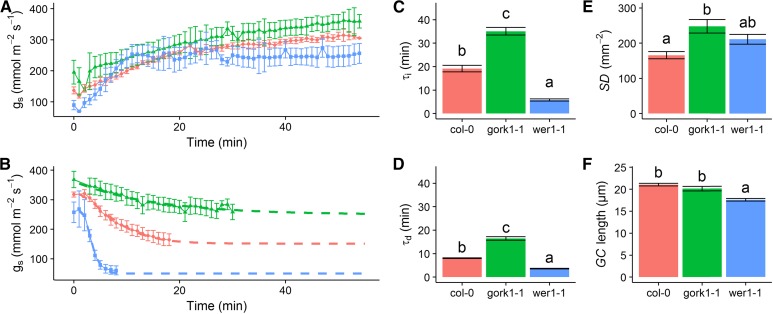

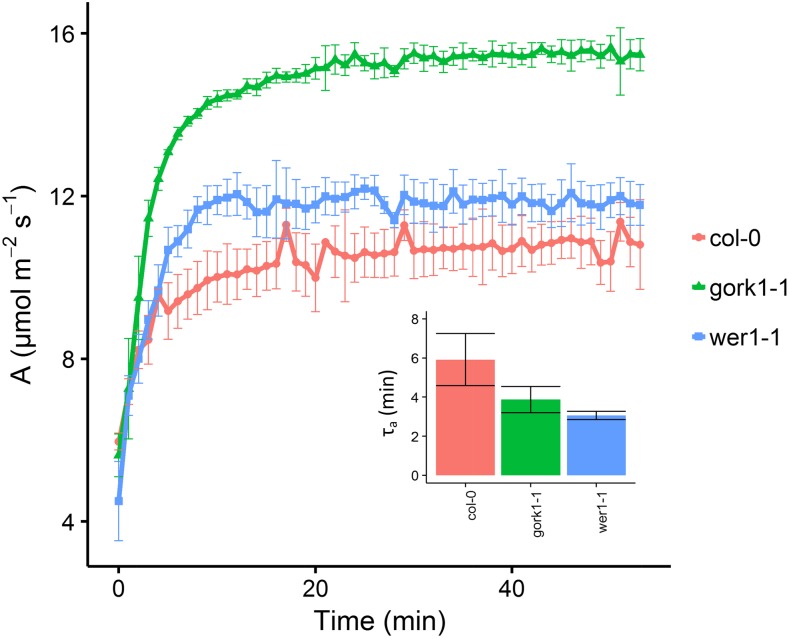

To illustrate the use of models to describe temporal gs responses and the effect of physical and functional stomatal attributes, we compared the rapidity of the temporal response of gs in two Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) genotypes and ecotype Col-0, one with altered stomatal distribution (wer1-1; Lee and Schiefelbein, 1999) and the second with impaired stomatal closure (gork1-1; Hosy et al., 2003). Compared with Col-0, the ectopic stomata of wer1-1 resulted in a faster stomatal response, as illustrated by the lower Gs (Fig. 2, A and B) and lower τi and τd (Fig. 2, C and D). The ectopic anatomy of the wer1-1 stomata potentially allows faster pore opening, as there is no back pressure from the surrounding epidermal cells because the stomatal guard cells are above and not in line with the epidermal cells, resulting in faster movements for the same energy cost. This change in stomatal anatomy also leads to a lower Gs compared with the wild-type control, although the mechanism for this is unknown and needs further investigation. As shown previously by Hosy et al. (2003), plants with impaired outward K+ channels (gork1-1) have greater τi and τd and higher Gs, resulting in a large unnecessary water loss during stomatal closure but little effect on stomatal limitation of A due to the relatively high values of gs. The strong reduction of the outwardly rectifying K+ channel activity in the guard cell membrane prevents K+ release and increases the stomatal aperture by maintaining membrane depolarization at membrane potentials more positive than the K+ equilibrium potential. This imbalance in osmoregulation induced a slow stomatal response by potentially slowing down K+ uptake. Although there were small but significant differences in anatomical features such as stomatal density (Fig. 2E) and guard cell length (Fig. 2F), they cannot explain the different temporal responses of gs in these plants, highlighting the importance of other parameters, such as the biochemistry and mechanics of stomatal movement as described above. The same conclusions can be drawn, for example, from studies of slac1 (Wang et al., 2012), amy3 and bam1 (Horrer et al., 2016), and other mutant and transgenic plants (Eisenach and de Angeli, 2017; Jezek and Blatt, 2017; Lunn and Santelia, 2017). These findings illustrate the plasticity of temporal gs responses and the potential impact that manipulating the speed of stomatal responses could have on A and WUE. For example, the fast gs response in the wer1-1 plants reduced gs limitation of A under an increase in light (Figs. 2A and 3) and reduced potential water loss when subjected to a decrease in light (Fig. 2B). These plants exhibited a potential for increased/greater synchronization between A and gs (Fig. 3), which may lead to higher WUE over the course of the day (McAusland et al., 2016).

Figure 2.

Temporal response of gs in Arabidopsis ecotypes (Col-0) and mutants (gork1-1 and wer1-1) following a step change in light intensity (from 100 to 1,000 µmol m−2 s−1 [A] and from 1,000 to 100 µmol m−2 s−1 [B]). Gas-exchange measurements of gs were recorded at 60-s intervals; leaf temperature was maintained at 25°C, and leaf VPD was maintained at 1 kPa. Time constants for an (C) increase (τi) and (D) decrease (τd) in gs were derived from the exponential model described in the text; (E) SD, stomatal density; (F) GC, guard cell. Letters represented the results of Tukey’s posthoc comparisons of group means.

Figure 3.

Temporal response of A in Arabidopsis (Col-0, gork1-1, and wer1-1) to a step change in light intensity (from 100 to 1,000 µmol m−2 s−1). Insert graph, the time constant (τa) to reach 63% of the steady-state A under 1,000 µmol m−2 s−1 light indicates the temporal limitation of A. Gas exchange was recorded at 60-s intervals; leaf temperature was maintained at 25°C, and leaf VPD was maintained at 1 kPa.

CONCLUSION

Despite stomatal behavior occurring at the microscale, it is important to recognize the impact they have on cycles of carbon and water in large-scale global systems. Although stomata typically occupy only a small portion of the leaf surface (0.3%–5%), they are known to control approximately 95% of all gas exchange between the leaf and environment, and estimations show that 98% of all water taken up through the roots may be transpired through stomatal pores (Morison, 2003), potentially translating to 60% of all terrestrial precipitation (Katul et al., 2012). Indeed, most crop plants will transpire over twice their fresh weight in water every day (Chaumont and Tyerman, 2014). With this in mind, stomata represent important targets for manipulating crop photosynthetic productivity and water use, which is particularly important considering that the allocation of fresh water resources is becoming a significant global concern. As highlighted in this review, the importance of the temporal response of gs is largely unknown and underestimated, and understanding this variation will aid future scaling efforts from individual stoma to leaf and canopy levels. What is apparent is the lack of quantitative data on the rapidity of the stomatal response under different environmental conditions, making it difficult to describe the mechanisms of guard cell movement and assess the impact of uncoordinated responses on leaf-level gas exchange. By integrating the dynamic or stomatal responses to changing environmental conditions, and taking account of different stomatal morphology as well as sensing and signaling systems, we may be able to maximize the benefit of photosynthesis (in terms of carbon gain) relative to the cost of water and translate these findings into more sustainable crop production systems for the future.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental File S1. GS_Fit.xlsm.

Supplementary Material

Glossary

- WUE

water use efficiency

- VPD

vapor pressure deficit

- PPFD

photosynthetic photon flux density

- Col-0

Columbia-0

Footnotes

This work was supported by Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (grant no. BB/I001187/1 to T.L. and H.G. and grant nos. BB/L019205/1 and BB/L001276/1 to M.R.B.) and Natural Environment Research Council (PhD) studentship grant no. Env-East DTP E14EE to J.S.A.M. and T.L.

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Aasamaa K, Sõber A (2011) Responses of stomatal conductance to simultaneous changes in two environmental factors. Tree Physiol 31: 855–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen MT, Pearcy RW (2000) Stomatal behavior and photosynthetic performance under dynamic light regimes in a seasonally dry tropical rain forest. Oecologia 122: 470–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arve LE, Kruse OMO, Tanino KK, Olsen JE, Futsæther C, Torre S (2017) Daily changes in VPD during leaf development in high air humidity increase the stomatal responsiveness to darkness and dry air. J Plant Physiol 211: 63–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assmann SM, Grantz DA (1990) Stomatal response to humidity in sugarcane and soybean: effect of vapour pressure difference on the kinetics of the blue light response. Plant Cell Environ 13: 163–169 [Google Scholar]

- Assmann SM, Wang XQ (2001) From milliseconds to millions of years: guard cells and environmental responses. Curr Opin Plant Biol 4: 421–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldocchi D. (2014) Measuring fluxes of trace gases and energy between ecosystems and the atmosphere: the state and future of the eddy covariance method. Glob Change Biol 20: 3600–3609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barman R, Jain AK, Liang M (2014) Climate-driven uncertainties in modeling terrestrial energy and water fluxes: a site-level to global-scale analysis. Glob Change Biol 20: 1885–1900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barradas VL, Jones HG (1996) Responses of CO2 assimilation to changes in irradiance: laboratory and field data and a model for beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). J Exp Bot 47: 639–645 [Google Scholar]

- Barradas VL, Jones HG, Clark JA (1994) Stomatal responses to changing irradiance in Phaseolus vulgaris L. J Exp Bot 45: 931–936 [Google Scholar]

- Bernacchi CJ, Kimball BA, Quarles DR, Long SP, Ort DR (2007) Decreases in stomatal conductance of soybean under open-air elevation of [CO2] are closely coupled with decreases in ecosystem evapotranspiration. Plant Physiol 143: 134–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonan GB, Williams M, Fisher RA, Oleson KW (2014) Modeling stomatal conductance in the earth system: linking leaf water-use efficiency and water transport along the soil-plant-atmosphere continuum. Geosci Model Dev 7: 2193–2222 [Google Scholar]

- Buckley TN, Mott KA (2013) Modelling stomatal conductance in response to environmental factors. Plant Cell Environ 36: 1691–1699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley TN, Mott KA, Farquhar GD (2003) A hydromechanical and biochemical model of stomatal conductance. Plant Cell Environ 26: 1767–1785 [Google Scholar]

- Chaumont F, Tyerman SD (2014) Aquaporins: highly regulated channels controlling plant water relations. Plant Physiol 164: 1600–1618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chazdon RL. (1988) Sunflecks and their importance to forest understorey plants. Adv Ecol Res 18: 1–63 [Google Scholar]

- Chazdon RL, Pearcy RW (1991) The importance of sunflecks for forest understory plants. Bioscience 41: 760–766 [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZH, Chen G, Dai F, Wang Y, Hills A, Ruan YL, Zhang G, Franks PJ, Nevo E, Blatt MR (2017) Molecular evolution of grass stomata. Trends Plant Sci 22: 124–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZH, Eisenach C, Xu XQ, Hills A, Blatt MR (2012) Protocol: optimised electrophyiological analysis of intact guard cells from Arabidopsis. Plant Methods 8: 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan IR, Farquhar GD (1977) Stomatal function in relation to leaf metabolism and environment. Symp Soc Exp Biol 31: 471–505 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damour G, Simonneau T, Cochard H, Urban L (2010) An overview of models of stomatal conductance at the leaf level. Plant Cell Environ 33: 1419–1438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies WJ, Kozlowski TT (1974) Stomatal responses of five woody angiosperms to light intensity and humidity. Can J Bot 52: 1525–1534 [Google Scholar]

- De Angeli A, Eisenach C (2017) Ion transport at the vacuole during stomatal movements. Plant Physiol 174: 520–530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Kauwe MG, Kala J, Lin YS, Pitman AJ, Medlyn BE, Duursma RA, Abramowitz G, Wang YP, Miralles DG (2015) A test of an optimal stomatal conductance scheme within the CABLE land surface model. Geosci Model Dev 8: 431–452 [Google Scholar]

- Dewar RC, Franklin O, Mäkelä A, McMurtrie RE, Valentine HT (2009) Optimal function explains forest responses to global change. Bioscience 59: 127–139 [Google Scholar]

- Doheny-Adams T, Hunt L, Franks PJ, Beerling DJ, Gray JE (2012) Genetic manipulation of stomatal density influences stomatal size, plant growth and tolerance to restricted water supply across a growth carbon dioxide gradient. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 367: 547–555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dow GJ, Berry JA, Bergmann DC (2014) The physiological importance of developmental mechanisms that enforce proper stomatal spacing in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol 201: 1205–1217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake PL, Froend RH, Franks PJ (2013) Smaller, faster stomata: scaling of stomatal size, rate of response, and stomatal conductance. J Exp Bot 64: 495–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont J, Spicher F, Montpied P, Dizengremel P, Jolivet Y, Le Thiec D (2013) Effects of ozone on stomatal responses to environmental parameters (blue light, red light, CO2 and vapour pressure deficit) in three Populus deltoides × Populus nigra genotypes. Environ Pollut 173: 85–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott-Kingston C, Haworth M, Yearsley JM, Batke SP, Lawson T, McElwain JC (2016) Does size matter? Atmospheric CO2 may be a stronger driver of stomatal closing rate than stomatal size in taxa that diversified under low CO2. Front Plant Sci 7: 1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Sharkey TD (1982) Stomatal conductance and photosynthesis. Annu Rev Plant Physiol 33: 317–345 [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, von Caemmerer S, Berry JA (1980) A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C3 species. Planta 149: 78–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fay PA, Knapp AK (1995) Stomatal and photosynthetic responses to shade in sorghum, soybean and eastern gamagrass. Physiol Plant 94: 613–620 [Google Scholar]

- Fischer RA, Rees D, Sayre KD, Lu ZM, Condon AG, Saavedra AL (1998) Wheat yield progress associated with higher stomatal conductance and photosynthetic rate, and cooler canopies. Crop Sci 38: 1467 [Google Scholar]

- Franks PJ, Beerling DJ (2009) Maximum leaf conductance driven by CO2 effects on stomatal size and density over geologic time. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 10343–10347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks PJ, Farquhar GD (2001) The effect of exogenous abscisic acid on stomatal development, stomatal mechanics, and leaf gas exchange in Tradescantia virginiana. Plant Physiol 125: 935–942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks PJ, Farquhar GD (2007) The mechanical diversity of stomata and its significance in gas-exchange control. Plant Physiol 143: 78–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks PJW, Doheny-Adams TW, Britton-Harper ZJ, Gray JE (2015) Increasing water-use efficiency directly through genetic manipulation of stomatal density. New Phytol 207: 188–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grantz DA, Zeiger E (1986) Stomatal responses to light and leaf-air water vapor pressure difference show similar kinetics in sugarcane and soybean. Plant Physiol 81: 865–868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington AM, Woodward FI (2003) The role of stomata in sensing and driving environmental change. Nature 424: 901–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hills A, Chen ZH, Amtmann A, Blatt MR, Lew VL (2012) OnGuard, a computational platform for quantitative kinetic modeling of guard cell physiology. Plant Physiol 159: 1026–1042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horie T. (1978) Studies on photosynthesis and primary production of rice plants in relation to meteorological environments. J Agric Meteorol 34: 125–136 [Google Scholar]

- Horrer D, Flütsch S, Pazmino D, Matthews JSA, Thalmann M, Nigro A, Leonhardt N, Lawson T, Santelia D (2016) Blue light induces a distinct starch degradation pathway in guard cells for stomatal opening. Curr Biol 26: 362–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosy E, Vavasseur A, Mouline K, Dreyer I, Gaymard F, Porée F, Boucherez J, Lebaudy A, Bouchez D, Very AA, et al. (2003) The Arabidopsis outward K+ channel GORK is involved in regulation of stomatal movements and plant transpiration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 5549–5554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iino M, Ogawa T, Zeiger E (1985) Kinetic properties of the blue-light response of stomata. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 82: 8019–8023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jezek M, Blatt MR (2017) The membrane transport system of the guard cell and its integration for stomatal dynamics. Plant Physiol 174: 487–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones HG. (2013) Plants and Microclimate: A Quantitative Approach to Environmental Plant Physiology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser E, Morales A, Harbinson J, Heuvelink E, Prinzenberg AE, Marcelis LFM (2016) Metabolic and diffusional limitations of photosynthesis in fluctuating irradiance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Sci Rep 6: 31252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser H, Kappen L (1997) In situ observations of stomatal movements in different light-dark regimes: the influence of endogenous rhythmicity and long-term adjustments. J Exp Bot 48: 1583–1589 [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser H, Kappen L (2000) In situ observation of stomatal movements and gas exchange of Aegopodium podagraria L. in the understorey. J Exp Bot 51: 1741–1749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser H, Kappen L (2001) Stomatal oscillations at small apertures: indications for a fundamental insufficiency of stomatal feedback-control inherent in the stomatal turgor mechanism. J Exp Bot 52: 1303–1313 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katul GG, Oren R, Manzoni S, Higgins C, Parlange MB (2012) Evapotranspiration: a process driving mass transport and energy exchange in the soil‐plant‐atmosphere‐climate system. Rev Geophys 50: RG3002 [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum MU, Pearcy RW (1988) Gas exchange analysis of the relative importance of stomatal and biochemical factors in photosynthetic induction in Alocasia macrorrhiza. Plant Physiol 86: 782–785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum MUF, Gross LJ, Pearcy RW (1988) Observed and modelled stomatal responses to dynamic light environments in the shade plant Alocasia macrorrhiza. Plant Cell Environ 11: 111–121 [Google Scholar]

- Knapp AK. (1993) Gas exchange dynamics in C3 and C4 grasses: consequence of differences in stomatal conductance. Plant Physiol 74: 113–123 [Google Scholar]

- Knapp AK, Smith WK (1987) Stomatal and photosynthetic responses during sun/shade transitions in subalpine plants: influence on water use efficiency. Oecologia 74: 62–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp AK, Smith WK (1988) Effect of water stress on stomatal and photosynthetic responses in subalpine plants to cloud patterns. Am J Bot 75: 851 [Google Scholar]

- Laffray D, Louguet P, Garrec JP (1982) Microanalytical studies of potassium and chloride fluxes and stomatal movements of two species: Vicia faba and Pelargonium × hortorum. J Exp Bot 33: 771–782 [Google Scholar]

- Lawson T, Blatt MR (2014) Stomatal size, speed, and responsiveness impact on photosynthesis and water use efficiency. Plant Physiol 164: 1556–1570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson T, James W, Weyers J (1998) A surrogate measure of stomatal aperture. J Exp Bot 49: 1397–1403 [Google Scholar]

- Lawson T, Kramer DM, Raines CA (2012) Improving yield by exploiting mechanisms underlying natural variation of photosynthesis. Curr Opin Biotechnol 23: 215–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson T, Morison JIL (2004) Stomatal function and physiology. In AR Hemsley, I Poole, eds, The Evolution of Plant Physiology; from whole plants to ecosystem. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 217–242 [Google Scholar]

- Lawson T, von Caemmerer S, Baroli I (2010) Photosynthesis and stomatal behaviour. In Lüttge UE, Beyschlag W, Büdel B, Francis D, eds, Progress in Botany. Springer, Berlin, pp 265–304 [Google Scholar]

- Lawson T, Weyers J (1999) Spatial and temporal variation in gas exchange over the lower surface of Phaseolus vulgaris L. primary leaves. J Exp Bot 50: 1381–1391 [Google Scholar]

- Leakey ADB, Scholes JD, Press MC (2005) Physiological and ecological significance of sunflecks for dipterocarp seedlings. J Exp Bot 56: 469–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebaudy A, Vavasseur A, Hosy E, Dreyer I, Leonhardt N, Thibaud JB, Véry AA, Simonneau T, Sentenac H (2008) Plant adaptation to fluctuating environment and biomass production are strongly dependent on guard cell potassium channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 5271–5276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MM, Schiefelbein J (1999) WEREWOLF, a MYB-related protein in Arabidopsis, is a position-dependent regulator of epidermal cell patterning. Cell 99: 473–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Kromdijk J, Heuvelink E, van Noort FR, Kaiser E, Marcelis LFM (2016) Effects of diffuse light on radiation use efficiency of two Anthurium cultivars depend on the response of stomatal conductance to dynamic light intensity. Front Plant Sci 7: 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunn J, Santelia D (2017) Transitory starch metabolism in guard cells: inique features for a unique function. Plant Physiol 174: 539–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield TA, Hetherington AM, Atkinson CJ (1990) Some current aspects of stomatal physiology. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 41: 55–75 [Google Scholar]

- Manzoni S, Vico G, Katul G, Fay PA, Polley W, Palmroth S, Porporato A (2011) Optimizing stomatal conductance for maximum carbon gain under water stress: a meta-analysis across plant functional types and climates. Funct Ecol 25: 456–467 [Google Scholar]

- Martins SCV, McAdam SAM, Deans RM, DaMatta FM, Brodribb TJ (2016) Stomatal dynamics are limited by leaf hydraulics in ferns and conifers: results from simultaneous measurements of liquid and vapour fluxes in leaves. Plant Cell Environ 39: 694–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAusland L, Davey PA, Kanwal N, Baker NR, Lawson T (2013) A novel system for spatial and temporal imaging of intrinsic plant water use efficiency. J Exp Bot 64: 4993–5007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAusland L, Vialet-Chabrand S, Davey P, Baker NR, Brendel O, Lawson T (2016) Effects of kinetics of light-induced stomatal responses on photosynthesis and water-use efficiency. New Phytol 211: 1209–1220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mencuccini M, Mambelli S, Comstock J (2000) Stomatal responsiveness to leaf water status in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) is a function of time of day. Plant Cell Environ 23: 1109–1118 [Google Scholar]

- Morison JIL. (2003) Plant water use, stomatal control. In Stewart BA, Howell TA, eds, Encyclopedia of Water Science. Marcel Dekker, New York, pp 680–685 [Google Scholar]

- Mott KA. (2009) Opinion: stomatal responses to light and CO2 depend on the mesophyll. Plant Cell Environ 32: 1479–1486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moualeu-Ngangue DP, Chen TW, Stützel H (2016) A modeling approach to quantify the effects of stomatal behavior and mesophyll conductance on leaf water use efficiency. Front Plant Sci 7: 875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naumburg E, Ellsworth DS (2000) Photosynthetic sunfleck utilization potential of understory saplings growing under elevated CO2 in FACE. Oecologia 122: 163–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naumburg E, Ellsworth DS, Katul GG (2001) Modeling dynamic understory photosynthesis of contrasting species in ambient and elevated carbon dioxide. Oecologia 126: 487–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noe SM, Giersch C (2004) A simple dynamic model of photosynthesis in oak leaves: coupling leaf conductance and photosynthetic carbon fixation by a variable intracellular CO2 pool. Funct Plant Biol 31: 1195–1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooba M, Takahashi H (2003) Effect of asymmetric stomatal response on gas-exchange dynamics. Ecol Modell 164: 65–82 [Google Scholar]

- Outlaw WH. (2003) Integration of cellular and physiological functions of guard cells. CRC Crit Rev Plant Sci 22: 503–529 [Google Scholar]

- Papanatsiou M, Amtmann A, Blatt MR (2016) Stomatal spacing safeguards stomatal dynamics by facilitating guard cell ion transport independent of the epidermal solute reservoir. Plant Physiol 172: 254–263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearcy RW. (1990) Photosynthesis in plant life. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 41: 421–453 [Google Scholar]

- Pearcy RW. (1994) Photosynthetic utilization of sunflecks: a temporally patchy resource on a time scale of seconds to minutes. In MM Caldwell, RW Pearcy, eds, Exploitation of Environmental Heterogeneity by Plants. Academic Press, San Diego, pp 175–208

- Pearcy RW, Way DA (2012) Two decades of sunfleck research: looking back to move forward. Tree Physiol 32: 1059–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poorter H, Fiorani F, Pieruschka R, Wojciechowski T, van der Putten WH, Kleyer M, Schurr U, Postma J (2016) Pampered inside, pestered outside? Differences and similarities between plants growing in controlled conditions and in the field. New Phytol 212: 838–855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porcar-Castell A, Palmroth S (2012) Modelling photosynthesis in highly dynamic environments: the case of sunflecks. Tree Physiol 32: 1062–1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu M, Hamdani S, Li W, Wang S, Tang J, Chen Z, Song Q, Li M, Zhao H, Chang T, et al. (2016) Rapid stomatal response to fluctuating light: an under-explored mechanism to improve drought tolerance in rice. Funct Plant Biol 43: 727–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raschke K. (1975) Stomatal action. Annu Rev Plant Physiol 26: 309–340 [Google Scholar]

- Raven JA. (2014) Speedy small stomata? J Exp Bot 65: 1415–1424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schymanski SJ, Or D, Zwieniecki M (2013) Stomatal control and leaf thermal and hydraulic capacitances under rapid environmental fluctuations. PLoS ONE 8: e54231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimazaki K, Doi M, Assmann SM, Kinoshita T (2007) Light regulation of stomatal movement. Annu Rev Plant Biol 58: 219–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y, Sugano SS, Shimada T, Hara-Nishimura I (2013) Enhancement of leaf photosynthetic capacity through increased stomatal density in Arabidopsis. New Phytol 198: 757–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinoco-Ojanguren C, Pearcy RW (1992) Dynamic stomatal behavior and its role in carbon gain during lightflecks of a gap phase and an understory Piper species acclimated to high and low light. Oecologia 92: 222–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinoco-Ojanguren C, Pearcy RW (1993) Stomatal dynamics and its importance to carbon gain in two rainforest Piper species. II. Stomatal versus biochemical limitations during photosynthetic induction. Oecologia 94: 395–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO World Water Assessment Programme (2009) The United Nations World Water Development Report 3: Water in a Changing World. Paris: UNESCO, and London: Earthscan http://www.unesco.org/new/en/natural-sciences/environment/water/wwap/wwdr/wwdr3-2009/downloads-wwdr3

- Urban O, Sprtová M, Kosvancová M, Tomásková I, Lichtenthaler HK, Marek MV (2008) Comparison of photosynthetic induction and transient limitations during the induction phase in young and mature leaves from three poplar clones. Tree Physiol 28: 1189–1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vialet-Chabrand S, Dreyer E, Brendel O (2013) Performance of a new dynamic model for predicting diurnal time courses of stomatal conductance at the leaf level. Plant Cell Environ 36: 1529–1546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vialet-Chabrand S, Matthews JSA, Brendel O, Blatt MR, Wang Y, Hills A, Griffiths H, Rogers S, Lawson T (2016) Modelling water use efficiency in a dynamic environment: an example using Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Sci 251: 65–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vialet-Chabrand S, Matthews JSA, Simkin AJ, Raines CA, Lawson T (2017) Importance of fluctuations in light on the acclimation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol 173: 2163–2179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vico G, Manzoni S, Palmroth S, Katul G (2011) Effects of stomatal delays on the economics of leaf gas exchange under intermittent light regimes. New Phytol 192: 640–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Hills A, Blatt MR (2014) Systems analysis of guard cell membrane transport for enhanced stomatal dynamics and water use efficiency. Plant Physiol 164: 1593–1599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Papanatsiou M, Eisenach C, Karnik R, Williams M, Hills A, Lew VL, Blatt MR (2012) Systems dynamic modeling of a guard cell Cl− channel mutant uncovers an emergent homeostatic network regulating stomatal transpiration. Plant Physiol 160: 1956–1967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Way DA, Pearcy RW (2012) Sunflecks in trees and forests: from photosynthetic physiology to global change biology. Tree Physiol 32: 1066–1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weyers JDB, Lawson T (1997) Heterogeneity in stomatal characteristics. Adv Bot Res 26: 317–352 [Google Scholar]

- Weyers JDB, Lawson T, Peng ZY (1997) Variation in stomatal characteristics at the whole-leaf level. In van Gardingen PR, Foody GM, Curran PJ, eds, SEB Seminar Series: Scaling Up. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, pp 129–149 [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead D, Teskey RO (1995) Dynamic response of stomata to changing irradiance in loblolly pine (Pinus taeda L.). Tree Physiol 15: 245–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willmer C, Fricker M (1996) Stomata. Springer Science & Business Media, London, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- Wong SC, Cowan IR, Farquhar GD (1979) Stomatal conductance correlates with photosynthetic capacity. Nature 282: 424–426 [Google Scholar]

- Wong SL, Chen CW, Huang HW, Weng JH (2012) Using combined measurements for comparison of light induction of stomatal conductance, electron transport rate and CO2 fixation in woody and fern species adapted to different light regimes. Tree Physiol 32: 535–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods DB, Turner NC (1971) Stomatal response to changing light by four tree species of varying shade tolerance. New Phytol 70: 77–84 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Xia X, Zhang Y, Gan SS (2012) An ABA-regulated and Golgi-localized protein phosphatase controls water loss during leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant J 69: 667–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.