Abstract

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) and substance use are highly prevalent conditions among military populations. There is a significant body of evidence that suggests greater approval of substance use (i.e., norms) is related to increased substance use. The objective of this work is to understand the impact of TBI and military service on substance use norms of soldiers and their partners. Data are from the baseline assessment of Operation: SAFETY, an ongoing, longitudinal study of US Army Reserve/National Guard (USAR/NG) soldiers and their partners. Multiple regression models examined associations between alcohol, tobacco, illicit drug use, and non-medical use of prescription drug (NMUPD) norms within and across partners based on current military status (CMS) and TBI. Male USAR/NG soldiers disapproved of NMUPD, illicit drug use and tobacco use. There was no relation between military status and alcohol use. Among females, there was no relation between CMS and norms. The NMUPD norms of wives were more likely to be approving if their husbands reported TBI symptoms and had separated from the military. Husbands of soldiers who separated from the military with TBI had greater approval of the use of tobacco, NMUPD, and illicit drugs. Overall, there is evidence to suggest that, while generally disapproving of substance use, soldiers and partners become more accepting of use if they also experience TBI and separate from the military. Future research should examine the longitudinal influence of TBI on substance use norms and subsequent changes in substance use over time.

Keywords: substance use, military, traumatic brain injury, marriage

1.0 Introduction

Substance use within the workplace is associated with detrimental effects that reaches beyond impairments in productivity to include negative health consequences [1–5]. Military workforces are not impervious to problematic substance use and its associated negative effects [6, 7]. When compared to the general population, service members have higher rates of substance use [8, 9]. In fact, substance abuse is one of the most commonly reported health problems among soldiers returning from Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) [10–13]. The use of tobacco is higher among service members than in the general population [6] and a long history of alcohol misuse has been chronicled [6, 12, 14]. Prescription drug misuse is also a concern [12, 14]. High rates of health problems in veterans of OEF/OIF exacerbates potentials for misuse. For instance, traumatic brain injury increases the likelihood of pain management plans involving opioids [15]. Examination of health related behaviors in active duty personnel found the lifetime, past year, and past month use of illicit and prohibited drugs in those 18–65 years of age to be 28.2%, 1.4%, and 0.3% respectively [16]. A cross-sectional study in veterans using the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system, found that 7% of OEF/OIF veterans screened positive for cocaine and marijuana use disorders [17].

Among military personnel, a number of factors may influence substance use. Demographic factors related to an increased likelihood of substance misuse include male gender, age less than 25 years, and being single (i.e., never married, widowed, or divorced) [18]. Combat exposure and a history of deployment are associated with increased substance use/misuse, though the specific branch of the military also influences different patterns of substance use [18]. Following deployment, United States Army Reserve/National Guard (USAR/NG) soldiers report higher rates of mental health problems and treatment needs for new-PTSD, depression, and substance abuse than their active duty counterparts [19–22].

Substance use norms are another influential factor associated with substance use [23, 24]. In particular, greater approval substance use is related to higher levels of use, while decreasing approval is related to lower levels of use [25–27]. For example, in civilians, peer alcohol use is a strong predictor of individual alcohol use [25–28]. Tobacco use is associated with self-identification as a smoker, tobacco outlets close to home, and perceptions that smoking is more prevalent than actual use [29–32]. Parental substance use, childhood perceptions of parental norms, and individual and friends’ norms all contribute to an increased likelihood of marijuana and alcohol use [24]. Research on prescription drug norms has found individuals to overestimate peers’ misuse [33].

Information concerning substance use norms is much more limited in the military than in civilian populations. However, given the higher rates of alcohol and tobacco use in the military as compared to the general population, it is possible that their underlying norms may differ. When asked about the alcohol consumption of their coworkers, military personnel overestimated the actual amount of alcohol consumed by their coworkers as well as the percentage of their coworkers who engaged in episodes of heavy drinking [34]. The more often that military personnel believed their coworkers drank, the frequency of their own alcohol use also increased [34, 35]. Soldiers’ norms may be subject to change over time as a result of exposure to a number of service conditions or changes in social, environmental, or health related factors that influence their substance use [15, 19–21]. One such influence is that of an intimate partner. Partner influences have been observed on each other’s physical health, mental health, and risk related behavior [36, 37]. Previous work with civilians found that one partner’s actual use of a given substance (e.g., alcohol, tobacco, illicit drugs, and nonmedical use of prescription drugs (NMUPD)) is predictive of their spouse’s use of the same substance [38–43]. Further, there is evidence in civilian populations that a partner’s expectations about substance use are related to their own substance use [44, 45]. Given the high proportion of service members who are married, there is a potential for partners to impact each other’s health behaviors [46]. As such, it is important to understand within (i.e., how one person’s behaviors impact his/her own behaviors) and cross-spouse (i.e., how one partner’s behaviors impact his/her partner’s behaviors) influences among soldiers and partners.

Another factor that may relate to changing substance use norms is separation from the military. Norman et al. [47] investigated the predictors of problematic substance use following discharge from the military and found that the majority of soldiers who screened positive for problematic substance use during active duty no longer screened positive during the year after separation from the military; however 42% of the sample continued to have problematic substance use

Appreciating other factors that negatively impact soldier wellbeing is also necessary as these factors may precipitate departure from the military or further influence substance use. One such vulnerability factor is stress. Common stressors in the military are related to injuries and deployment [20, 48–52]. Combat-related traumatic brain injuries (TBI) and their detrimental aftereffects have been a major longstanding concern [53]. It is possible that health conditions, such as TBI, can impact substance use norms.

1.1 Purpose of the present study

Given the high percentage of married soldiers coupled with a higher prevalence of substance abuse among USAR/NG than active duty soldiers, the primary objective of this study was to explore how TBI and current military status (CMS) relate to the couples’ substance use related norms. Importantly, we examined within spouse effects (e.g., his behaviors impacting his norms) and cross spouse (e.g., his behaviors impacting her norms) effects.

2.0 Methods

The Operation: SAFETY (Soldiers and Families Excelling Through the Years) study protocol was approved by The State University of New York (SUNY) at Buffalo’s Institutional Review Board and also vetted by the Army Human Research Protections Office, Office of the Chief, Army Reserve as well as the Adjutant General of the National Guard.

2.1 Recruitment

After coordinating with unit commanders, Operation SAFETY staff were able to attend unit drills to present a brief project overview to soldiers and distribute study information packets to soldiers to take home to share with their partners. The 10-minute briefing detailed study objectives and protocols, what participation would involve, topics covered in the questionnaire, and confidentiality. Soldiers and their partners each received $60 for baseline and $70 for each of the yearly follow-ups ($200 per person/$400 couple over the study period). Soldiers were told that investigators had obtained a certificate of confidentiality from the US Department of Health and Human Services that prevents disclosure of their information in response to legal orders. Assurances were made that not only would the military not know of their participation, but partners would not learn of each other’s responses. To conclude, soldiers were invited to complete a one-page screening form.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) the couple is married or living as if married; (2) one member of the dyad is a current USAR/NG Soldier; (3) the soldier is 18–45 years of age; (4) both partners are able to speak and understand English; (5) both partners are willing and able to participate; and (6) both partners have had at least one alcoholic beverage in the past year. Assessment surveys were scheduled for eligible couples who verbalized their willingness to participate.

Over 15-months, we attended 47 recruitment events at units across New York State. We received 1653 completed screening forms; 922 were ineligible (579 were single, 329 failed ≥1 screening items (M=1.5(SD: 0.09)). Of the 731 eligible, 572 (78%) agreed to participate and 83% of couples (N=472) completed at least part of the survey. Among males, 435 completed the entire survey, while 7 started but did not finish. Female participants completed 440 surveys and 14 additional surveys were partially completed. There were 7 same sex couples. Only surveys where both partners completed the entire survey were included for follow-up (N=411). We examined the differences between those that passed and enrolled vs those who passed and did not enroll after screening. When a civilian partner screened for the study (n=11), these couples were less likely to enroll (p<.001). No differences existed within the soldiers’ screening health variables between those who enrolled and completed compared to those who enrolled and did not complete. The data presented are from a subset of the main study based upon soldiers who were deployed and their partners.

2.2 Participants

The sample for this report is comprised of (248 male soldiers (MS) and 34 female soldiers (FS); Table 1) USAR/NG Soldiers and their partners. Both male and female soldiers served an average of 11 years (males (M(SD)): 11.9 (6.0); females 11.3 (4.0)) of military service. The sample is mostly non-Hispanic White (male soldiers and partners: 81% and 89% respectively; female soldiers and partners: 76% and 71% respectively). Both male and female soldiers had at least some college education (60% MS; 50% FS) or a college degree (26% MS; 47% FS). Male soldier partners (MSP) and female soldier partners (FSP) also had some college education (42% MSP; 50 FSP) or a college degree (48% MSP; 47%FSP). Average gross household income was $60,000 to $79,999. Soldiers and partners were in their early thirties (MS: Mean (SD) 33.4 (6.2) and their partners (32.0(6.5); FS: 33.2 (4.7) and their partners (34.3 (5.9)) and mostly married (MS: 75.4%; FS: 76.5%).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of male and female USAR/NG soldiers and their partners with combat experience.

| Male Soldiers and Partners | Female Soldiers and Partners | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Characteristic | Husbands (n=248) % (n) or x̄ (sd) |

Wives (n=248) % (n) or x̄ (sd) |

Wives (n=34) % (n) or x̄ (sd) |

Husbands (n=34) % (n) or x̄ (sd) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 81.1% (201) | 88.7% (220) | 76.5% (26) | 70.6% (24) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 4.5% (11) | 1.2% (3) | 2.9% (1) | 8.8% (3) |

| Hispanic | 9.7% (24) | 5.2% (13) | 11.8% (4) | 11.8% (4) |

| Other | 3.2% (8) | 3.6% (9) | 5.8% (2) | 5.9% (2) |

|

| ||||

| Education | ||||

| <HS – HS Grad | 14.1% (35) | 9.2% (23) | 2.9% (1) | 17.7% (6) |

| Some College | 60.1% (149) | 42.3% (105) | 50.0% (17) | 44.1% (15) |

| College + | 25.8% (64) | 48.4% (120) | 47.1% (16) | 38.2% (13) |

|

| ||||

| Age | 33.4 (6.2) | 32.0 (6.49) | 33.2 (4.7) | 34.3 (5.9) |

|

| ||||

| Married/Cohabitating | 75.4% (187) / 24.6% (61) | 76.5% (26) / 23.5% (8) | ||

|

| ||||

| Years Served | 11.9 (6.0) | 8.0 (4.6) | 11.3 (4.0) | 11.8 (7.6) |

|

| ||||

| Number of Deployments | 1.6 (0.9) | 1.3 (.49) | 1.3 (0.5) | 2.0 (1.2) |

2.3 Survey Administration

After completing an informed consent, surveys were administered using secure HIPAA-compliant online survey programming software, StudyTrax™ which allowed for data encryption. The baseline survey took approximately 2 ½ hours to complete while follow-up surveys lasted 90-minutes.

2.4 Measures

2.4.1 Perceived approval of substance use (norms)

Participants were asked three questions on a seven-point Likert scale concerning the acceptability of alcohol, tobacco, NMUPD, and illicit drugs. These questions (“People who are important to me think I [should not-should use] [substance]”; “People who are important to me would [disapprove-approve] of my using [substance]”; and, “People who are important to me want me to use [substance] [unlikely—likely]”) are based on the work of Armitage and colleagues [56]. All three items were summed to create a substance use norms summary score. Lower scores are indicative of greater substance use disapproval, while higher scores suggest greater approval. This scale had a reliability of .77 in husbands and .78 in wives.

2.4.2 Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

TBI was assessed using the three-item Brief Traumatic Brain Injury Scale [57]. Soldiers were asked if any of various types of injuries occurred while deployed (e.g., blast, fragment, vehicular, etc.), the severity of injury (e.g., being dazed, no memory, lost consciousness for various lengths, etc.), and if they were currently experiencing any injury-related problems. Symptoms resulting from a head injury or concussion was dichotomized into experiencing versus not experiencing TBI symptoms.

2.4.3 Current Military Status (CMS)

Participants’ responses were dichotomized into yes or no based on reports of current versus completed military service status.

2.5 Analytic Plan

Multiple linear regression models examined associations between substance use (alcohol, tobacco, NMUPD, and illicit drugs) norms both within and across couples based on CMS and TBI. Within spouse models examined the impact of a soldier’s CMS and TBI on his/her own norms. Cross spouse models examined the impact of a soldier’s CMS and TBI on his/her partner’s norms. Subsequent models examined the interaction between CMS and TBI.

3.0 Results

3.1 Descriptive Statistics

Among soldiers who were deployed, 24% (N= 60) of the males screened positive for TBI as did 24% (N= 8) of the females. Four percent of male soldiers and 18% of female soldiers separated from the military. Among male soldiers, the mean (standard deviation) scores for substance use norms were: alcohol (9.8 (4.4)), tobacco (5.3 (3.2)), NMUPD (4.2 (2.6)), and illicit drug use (4.2 (2.5). For their partners, normative scores were: alcohol (9.3 (4.3)), tobacco (4.4 (2.3)), NMUPD (4.2 (2.3)), and illicit drug use (4.2 (2.4)). Among female soldiers, normative scores were: alcohol (9.3 (4.2)), tobacco (4.7 (2.8)), NMUPD (4.3 (2.5)), and illicit drug use (4.2 (2.5). For their partners, normative scores were: alcohol (9.4 (4.2)), tobacco (4.4 (2.3)), NMUPD (4.3 (2.4)), and illicit drug use (4.2 (2.2)).

3.2 Main Effects

3.2.1 Within Spouse Effects

To examine the within spouse effects, we used Ordinary Least Squares regression models to identify the impact of Current Military Status (CMS) and TBI on his or her own perceived normative beliefs (i.e., approval) regarding alcohol, tobacco, NMUPD, and illicit drug use.

3.2.1.1 Husbands’ Norms Based on His CMS and TBI

Among men, CMS and TBI had no significant association with their alcohol-related norms. However, men in the military were less approving of other substance use. Specifically, being in the military was negatively associated with husbands’ tobacco norms (β = −2.55, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: −4.82, −0.28; p < .05). Additionally, husbands in the military had lower approval of both NMUPD (β = −2.24, 95% CI: −4.04, −0.44; p<.05) and illicit drug use (β = −2.23, 95% CI: −4.02, −0.45; p < .05). TBI was not significantly associated with tobacco, NMUPD, or illicit drug use.

3.2.1.2 Wives’ Norms Based on Her CMS and TBI

Wives’ CMS was not related to any of the substance use norms. Women soldiers who screened positive for TBI had lower approval of alcohol use (β = −3.48, 95% CI: −6.87, −0.09; p < .05). Among women, TBI was not related to any other substance use norms.

3.2.2 Cross Spouse Effects

Similar regression models were used to identify cross-spouse effects, or the impact of Current Military Status and TBI on their spouses’ perceived approval.

3.2.2.1 Husbands’ Norms Based on Her CMS and TBI

Wives’ CMS was not associated with any of her husbands’ substance use related norms. However, there was some evidence suggesting a relationship between wives’ TBI symptoms and husbands’ approval of alcohol use such that wives with TBI had husbands with lower perceived approval of alcohol (β = −3.30, 95% CI: −6.67, 0.06; p = .05).

3.2.2.2 Wives’ Norms Based on His CMS and TBI

Husbands’ CMS and TBI symptoms were only associated with wives’ NMUPD related norms. Specifically, there was some evidence indicating a negative association between husbands’ CMS and wives’ NMUPD norms (β = −1.49, 95% CI: −3.11, 0.13, p = .07), suggesting wives whose husbands were in the military had lower approval of NMUPD. Husbands with TBI symptoms had wives with higher approval of NMUPD (β = 0.73, 95% CI: .06, 1.40; p < .05).

3.3 Interaction Effects

To examine the potential effects of an interaction between CMS and TBI symptoms on norms, an interaction term was added to each regression model. Predictive margins were also calculated to determine the stratum-specific interactions between CMS and TBI on norms.

3.3.1 Within Spouse Effects

3.3.1.1 Husbands’ Norms Based on His CMS and TBI

No significant interactions were found between husbands’ CMS and TBI on his norms.

3.3.1.2 Wives’ Norms Based on Her CMS and TBI

No significant interactions were found between wives’ CMS and TBI on her norms.

3.3.2 Cross Spouse Effects

3.3.2.1 Husbands’ Norms Based on Her CMS and TBI

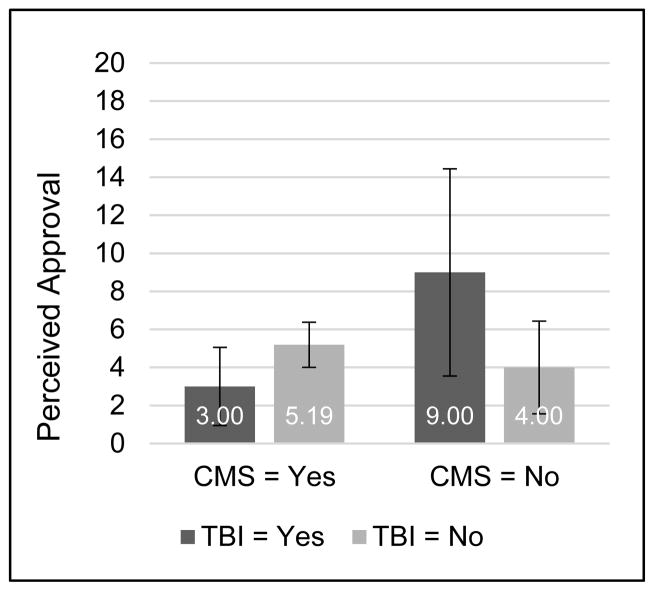

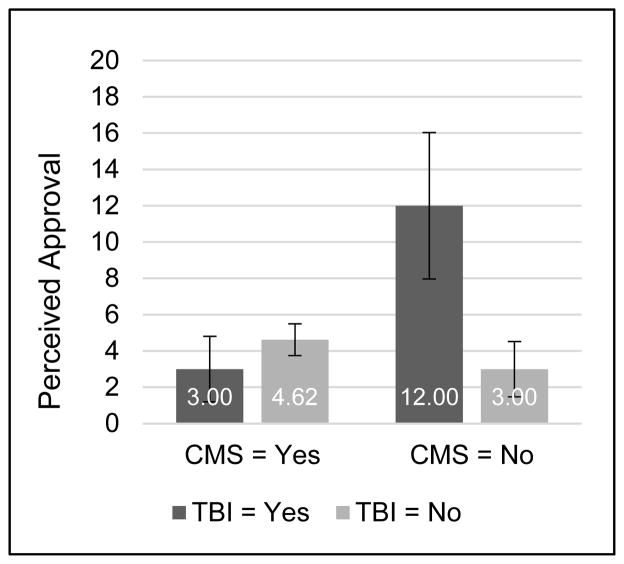

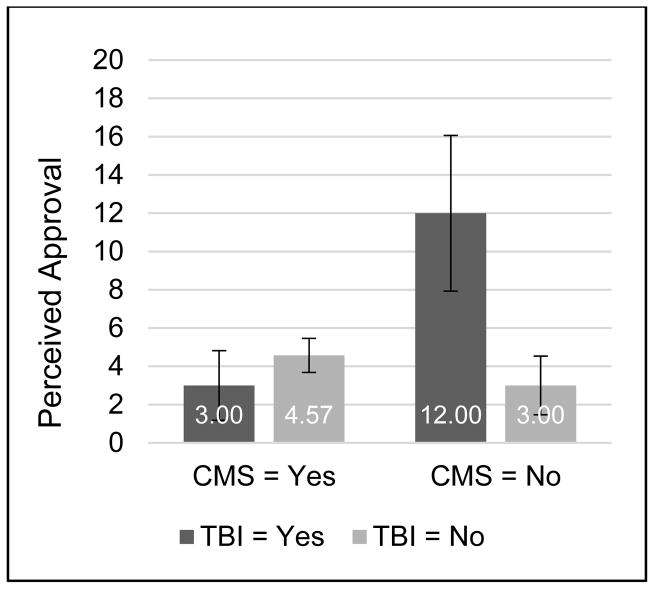

TBI symptoms in wives had a significant interaction with her CMS on husbands’ tobacco use norms (β = −7.19, 95% CI: −13.61, −0.77, p < .05), NMUPD norms (β = −10.62, 95% CI: −15.37, −5.86, p < .001), and illicit drug use norms (β = −10.57, 95% CI: −15.37, −5.77, p < .001). Predictive margins show that husbands were more likely to approve of tobacco use (p = .002), NMUPD (p < .001), and illicit drug use (p < .001) when their wives were no longer in the military and reported TBI symptoms (Figures 1, 2, and 3, respectively). There was no significant interaction for husbands’ alcohol norms.

Figure 1.

Husbands’ tobacco use perceived approval by wives’ CMS and TBI status.

Figure 2.

Husbands’ NMUPD perceived approval by wives’ CMS and TBI status.

Figure 3.

Husband’s illicit drug use perceived approval by wives’ CMS and TBI status.

3.3.2.2 Wives’ Norms Based on His CMS and TBI

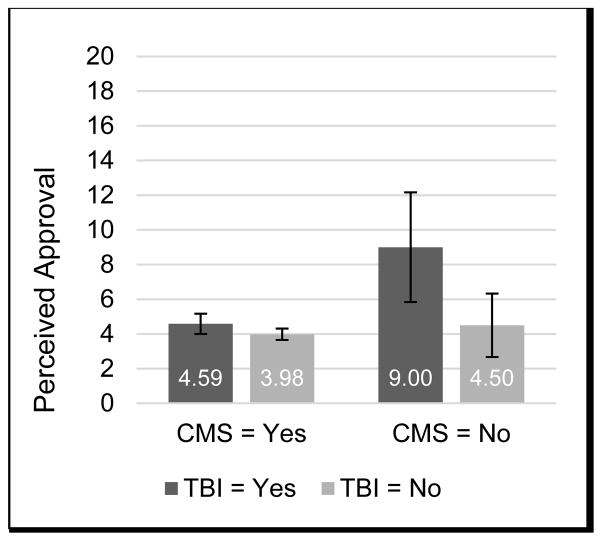

TBI symptoms in husbands had a significant interaction with his CMS on wives’ NMUPD norms (β = −3.90, 95% CI: −7.61, −0.18, p < .05). Predictive margins show that wives were most likely to approve of NMUPD (p < .001) when their husbands were no longer in the military and reported TBI symptoms (Figure 4). There were no significant interaction effects for alcohol, tobacco, or illicit drug use.

Figure 4.

Wives’ NMUPD perceived approval by husbands’ CMS and TBI status.

4.0 Discussion

This study is among the first to report substance use norms in a sample of soldiers and their spouses. The current study was also the first to examine factors that may change substance use norms for soldiers and partners, in particular, TBI and current military status. Results demonstrated that husbands currently in the military disapproved of the use of tobacco, NMUPD, and illicit drugs. Among women, military service was also not related to substance use norms. Our most noteworthy observations involved the interaction between current/separated military status and TBI which demonstrated significant cross spouse effects (that is, one person’s circumstances impacted their partner’s norms). More specifically, husbands were more likely to be approving of NMUPD, tobacco use, and illicit drug use if their partners had TBI symptoms and had separated from the military. Similarly, wives had greater approval of NMUPD if their partners had TBI symptoms and separated from the military.

It is plausible that the spouses of reservists became more accepting of their husbands/wives use of NMUPD and in some cases other substances because, now acutely aware of partners’ impairments, became open to possibilities that mitigate impairments. Essentially, the more amenable attitudes concerning their partners’ use of substances after they have separated from the military likely originate from their expectations of symptom palliation and/or self-medication back to former levels of functioning.

Our findings that spouses’ of USAR/NG soldiers shift to more approving substance use norms should partners report TBI symptoms after separating from the military is especially concerning considering reservists face a greater risk for substance abuse, mental health, and readjustment challenges than other soldiers. Susceptibility to these problems and the use of opioids for pain management certainly suggests that reservists may be at a high risk for worse outcomes, thus warranting targeted TBI intervention and management.

Irrespective of other influences on soldier wellbeing, simply returning to civilian life after separating from the military can be difficult for some individuals. Soldiers who report difficulty readjusting to civilian life are more likely to engage in problematic substance use [12, 47]. Post-deployment this is especially a concern for USAR/NG soldiers as they report a greater psychiatric burden along with more difficulties readjusting to civilian life than active duty counterparts [8, 61]. The mental health and substance-related treatment needs of reservists are more substantial also [19–22]. The most frequent reintegration challenges relate to problems accessing health care, family life and relationship difficulties, uncertainty of employment, expectations of a smooth readjustment, and rapid resumption of pre-deployment civilian roles [8, 20, 61].

The environment to which soldiers are returning offers added complexity to reintegration. Often community norms and behavior are likely dissimilar to those found within the military, which have influenced soldier norms and behavior prior to separation. This is demonstrated by Golub and Bennett in their examination of substance use in veterans returning to low-income, predominantly minority communities [62]. Prior to military service, the majority of the sample reported marijuana as the only substance used. While serving, marijuana use was significantly lower, problematic alcohol use (binge and heavy drinking) became a concern, and misuse of prescription drugs was newly initiated in six percent of the sample. After separating, marijuana use increased, problematic alcohol use decreased, and seven percent of the sample continued to misuse prescription drugs. Initiations of NMUPD during deployment and a continuation of misuse is problematic and suggestive of prescription drug seeking activity after separation.

Because our results depict that reservists’ spouses are at risk of developing more lenient substance norms when their partner is symptomatic and no longer in the military, there may be great value in including spouses in management plans. Future longitudinal research in reservists and their spouses is needed to examine influences of TBI on substance use norms and actual substance use changes over time in this population. Research documenting the efficacies of intervention and management strategies uniquely tailored to USAR/NG veterans that also incorporate spousal participation are also merited.

Limitations

This study has a few limitations. The data analyzed in this study were cross-sectional in nature. We acknowledge that our sample yielded comparatively few female soldiers with combat exposure. However, until recently, this was not uncommon as women were restricted from participating in many combat roles. Our TBI measure was analyzed as a dichotomous variable (i.e., symptoms versus no symptoms) leaving pertinent TBI related details such as mechanism and severity of injury, symptom specification, and objective assessments unaccounted for. Nonetheless, the results of analyses provided novel information about underlying substance use norms in an understudied population.

5.0 Conclusion

USAR/NG soldiers and their spouses generally disapprove of the use of substances. However, when soldiers report persisting TBI symptoms after separating from the military, spouses report greater approval of NMUPD and in certain cases tobacco and illicit drug use. Future work should examine how changing norms impact changes in actual substance use for both soldiers and their partners.

References

- 1.DeFulio A, et al. Employment-based abstinence reinforcement as a maintenance intervention for the treatment of cocaine dependence: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2009;104(9):1530–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02657.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DMB. The U.S. Mandatory Guidelines for Federal Workplace Drug Testing Programs: current status and future considerations. Forensic Sci Int. 2008;174(2–3):111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Normand J, Lempert RO, O’Brien CP. Under the influence? : drugs and the American work force. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 1994. p. 321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phillips JA, HM, Baldwin DD, Gifford-Meuleveld L, Mueller KL, Perkison B, Upfal M, Dreger M. Marijuana in the Workplace: Guidance for Occupational Health Professionals and Employers: Joint Guidance Statement of the American Association of Occupational Health Nurses and the American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. Workplace Health Saf. 2015;63(4):139–164. doi: 10.1177/2165079915581983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hourani LL, Williams TV, Kress AM. Stress, mental health, and job performance among active duty military personnel: findings from the 2002 Department of Defense Health-Related Behaviors Survey. Mil Med. 2006;171(9):849–56. doi: 10.7205/milmed.171.9.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bray RM, Hourani LL. Substance use trends among active duty military personnel: findings from the United States Department of Defense Health Related Behavior Surveys, 1980–2005. Addiction. 2007;102(7):1092–1101. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Department of Defense Directives 1010.4, D.a.A.U.b.D.P. DoD Policy of drug and alcohol abuse. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas JL, et al. Prevalence of mental health problems and functional impairment among active component and National Guard soldiers 3 and 12 months following combat in Iraq. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):614–23. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisen SA, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of psychiatric disorders in 8,169 male Vietnam War era veterans. Mil Med. 2004;169(11):896–902. doi: 10.7205/milmed.169.11.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kulesza M, et al. Help-Seeking Stigma and Mental Health Treatment Seeking Among Young Adult Veterans. Mil Behav Health. 2015;3(4):230–239. doi: 10.1080/21635781.2015.1055866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seal KH, et al. Bringing the war back home: mental health disorders among 103,788 US veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan seen at Department of Veterans Affairs facilities. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(5):476–82. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennett AS, Elliott L, Golub A. Opioid and other substance misuse, overdose risk, and the potential for prevention among a sample of OEF/OIF veterans in New York City. Subst Use Misuse. 2013;48(10):894–907. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.796991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bray RM, et al. 2008 Department of Defense Survey of Health Related Behaviors Among Active Duty Military Personnel: A Component of the Defense Lifestyle Assessment Program (DLAP) RTI International; Research Triangle Park, NC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bray RM, Marsden ME, Peterson MR. Standardized Comparisons of the Use of Alcohol, Drugs, and Cigarettes among Military Personnel and Civilians. American Journal of Public Health. 1991;81(7):865–869. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.7.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seal KH, et al. Association of mental health disorders with prescription opioids and high-risk opioid use in US veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. JAMA. 2012;307(9):940–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bondurant S, Wedge R, editors. Institute of Medicine. Combating Tobacco Use in Military and Veteran Populations. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009. p. 380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hawkins EJ, et al. Recognition and management of alcohol misuse in OEF/OIF and other veterans in the VA: A cross-sectional study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;109(1–3):147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seal KH, et al. Substance use disorders in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans in VA healthcare, 2001–2010: Implications for screening, diagnosis and treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;116(1–3):93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobson IG, et al. Alcohol use and alcohol-related problems before and after military combat deployment. JAMA. 2008;300(6):663–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.6.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Milliken CS, Auchterlonie JL, Hoge CW. Longitudinal assessment of mental health problems among active and reserve component soldiers returning from the Iraq war. JAMA. 2007;298(18):2141–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.18.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith TC, et al. Prior assault and posttraumatic stress disorder after combat deployment. Epidemiology. 2008;19(3):505–12. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31816a9dff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riddle JR, et al. Millennium Cohort: the 2001–2003 baseline prevalence of mental disorders in the U.S. military. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(2):192–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Measham F, Newcombe R, Parker H. The normalization of recreational drug use amongst young people in north-west England. Br J Sociol. 1994;45(2):287–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bailey JA, et al. Associations Between Parental and Grandparental Marijuana Use and Child Substance Use Norms in a Prospective, Three-Generation Study. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(3):262–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leonard KE, Kearns J, Mudar P. Peer networks among heavy, regular and infrequent drinkers prior to marriage. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61(5):669–73. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delucchi KL, Matzger H, Weisner C. Alcohol in emerging adulthood: 7-year study of problem and dependent drinkers. Addict Behav. 2008;33(1):134–42. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andrews JA, et al. The influence of peers on young adult substance use. Health Psychol. 2002;21(4):349–57. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Homish GG, Leonard KE. The social network and alcohol use. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69(6):906–14. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schleicher NC, et al. Tobacco outlet density near home and school: Associations with smoking and norms among US teens. Prev Med. 2016;91:287–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lipperman-Kreda S, et al. Density and Proximity of Tobacco Outlets to Homes and Schools: Relations with Youth Cigarette Smoking. Prevention Science. 2014;15(5):738–744. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0442-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McLaughlin I. Tobacco Control Legal Consortium, License to Kill?: Tobacco Retailer Licensing as an Effectivve Enforcement Tool. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ilakkuvan V, et al. What Does Having Your Pack in Your Pocket Say About You? Characteristics and Attitude Differences of Youth Carrying Tobacco at a Music Festival. Health Educ Behav. 2016 doi: 10.1177/1090198116643964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kilmer JR, et al. Normative perceptions of non-medical stimulant use: associations with actual use and hazardous drinking. Addict Behav. 2015;42:51–6. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neighbors C, et al. Normative Misperceptions of Alcohol Use Among Substance Abusing Army Personnel. Military Behavioral Health. 2014;2(2):203–209. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams J, et al. Mediating mechanisms of a military Web-based alcohol intervention. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;100(3):248–57. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Homish GG, Leonard KE. Spousal influence on general health behaviors in a community sample. Am J Health Behav. 2008;32(6):754–63. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2008.32.6.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Derrick JL, Leonard KE, Homish GG. Perceived partner responsiveness predicts decreases in smoking during the first nine years of marriage. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(9):1528–36. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dollar KM, et al. Spousal and alcohol-related predictors of smoking cessation: a longitudinal study in a community sample of married couples. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(2):231–3. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.140459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Homish GG, Leonard KE. Spousal influence on smoking behaviors in a US community sample of newly married couples. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(12):2557–67. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Homish GG, Leonard KE, Cornelius JR. Predictors of marijuana use among married couples: the influence of one’s spouse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;91(2–3):121–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Homish GG, Leonard KE, Cornelius JR. Individual, partner and relationship factors associated with non-medical use of prescription drugs. Addiction. 2010;105(8):1457–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02986.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leonard KE, Homish GG. Changes in Marijuana Use Over the Transition Into Marriage. J Drug Issues. 2005;35(2):409–429. doi: 10.1177/002204260503500209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith PH, et al. Women ending marriage to a problem drinking partner decrease their own risk for problem drinking. Addiction. 2012;107(8):1453–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leonard KE, Homish GG. Predictors of heavy drinking and drinking problems over the first 4 years of marriage. Psychol Addict Behav. 2008;22(1):25–35. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Homish GG, Leonard KE. Marital quality and congruent drinking. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66(4):488–96. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Department of Defense. Annual Report to the Congressional Defense Committees on Plans for the Department of Defense for the Support of Military Family Readiness, Fiscal Year 2012. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Norman SB, Schmied E, Larson GE. Predictors of continued problem drinking and substance use following military discharge. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75(4):557–66. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoge CW, et al. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems and barriers to care. US Army Med Dep J. 2008:7–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoge CW, et al. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(1):13–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken CS. Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA. 2006;295(9):1023–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.9.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mental Health Advisory Team (MHAT-V) Operation Iraqi Freedom 06-08: Iraq, Operation Enduring Freedom 8: Afghanistan. Office of the Surgeon Multi-National Force-Iraq and Office of the Command Surseon and Office of The Surgeon General United States Army Medical Command; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grieger TA, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in battle-injured soldiers. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(10):1777–83. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.10.1777. quiz 1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Institute of Medicine. Gulf War on Health. Vol. 7. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2008. Long-term Consequences of Traumatic Brain Injury. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Management of Concussion/mTBI Working Group. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Concussion/Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Version 2.0. Veterans Health Administration and Department of Defense; Wasington, DC: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carlson KF, et al. Psychiatric diagnoses among Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans screened for deployment-related traumatic brain injury. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23(1):17–24. doi: 10.1002/jts.20483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Armitage CJ, et al. Different Perceptions of Control: Applying an Extended Theory of Planned Behavior to Legal and Illegal Drug Use. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 1999;21(4):301–316. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schwab KA, et al. Screening for traumatic brain injury in troops returning from deployment in Afghanistan and Iraq: initial investigation of the usefulness of a short screening tool for traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 2007;22(6):377–89. doi: 10.1097/01.HTR.0000300233.98242.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Comper P, et al. A systematic review of treatments for mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2005;19(11):863–80. doi: 10.1080/02699050400025042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Snell DL, et al. A systematic review of psychological treatments for mild traumatic brain injury: an update on the evidence. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2009;31(1):20–38. doi: 10.1080/13803390801978849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ghaffar O, et al. Randomized treatment trial in mild traumatic brain injury. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61(2):153–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Castenada LW, Harrell MC, Varda DM. R. Corporation, editor. Deployment experiences of guard and reserve families: Implications for support and retention. Arlington, VA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Golub A, Bennett AS. Substance use over the military-veteran life course: an analysis of a sample of OEF/OIF veterans returning to low-income predominately minority communities. Addict Behav. 2014;39(2):449–54. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]