Summary

An unanswered question in human health is whether anti-oxidation prevents or promotes cancer. Anti-oxidation has historically been viewed as chemo-preventive but emerging evidence suggests that antioxidants may be supportive of neoplasia. We posit this contention to be rooted in the fact that ROS do not operate as one single biochemical entity, but as diverse secondary messengers in cancer cells. This cautions against therapeutic strategies to increase ROS at a global level. To leverage redox alterations towards the development of effective therapies necessitates the application of biophysical and biochemical approaches to define redox dynamics and to functionally elucidate specific oxidative modifications in cancer versus normal cells. An improved understanding of the sophisticated workings of redox biology is imperative to defeating cancer.

ROS Lie at the Heart of all Lives

Reduction-oxidation (Redox) chemical reactions in which the oxidation states of atoms are changed, represent a principle constituent of all life. Despite this, our current understanding of redox biochemistry inside living cells remains surprisingly elusive in both physiological and pathological settings. Molecular oxygen is a di-radical and is relatively unreactive. However, incomplete reduction of oxygen leads to the formation of chemically more reactive species called reactive oxygen species (ROS), a collective term that includes the superoxide anion (O2−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and hydroxyl radical (HO•). Due to their greater chemical reactivity, ROS are traditionally thought to exclusively mediate the toxicity of oxygen. As such, ROS have been associated with the principle of oxidative stress mediating pathology as they are considered to be damaging agents that can structurally and/or functionally compromise macromolecules such as nucleic acids, proteins and lipids (Cross et al., 1987). Oxidative stress occurs when there is a net increase in ROS and this has been implicated in carcinogenesis (Cross et al., 1987), neurodegeneration (Andersen, 2004), atherosclerosis (Mugge, 1998), diabetes (Paravicini and Touyz, 2006) and aging (Haigis and Yankner, 2010).

In the context of tumorigenesis, there is much excitement over the possibility of harnessing differences in cellular redox states to develop novel therapeutic strategies. Much effort has been invested in defining the role of ROS as a tumor promoting or a tumor-suppressing agent, with abundant evidence supporting either argument. This presents a conundrum on how we should approach ROS therapy in cancer. Perhaps an element underlying this conundrum is the fact that ROS involvement in pathogenesis is not confined to macromolecular damage, but is mediated through specific ROS-driven signaling events. The concept that ROS can operate as critical intracellular signaling molecules through oxidative modification of cysteine residues is widely documented in the literature (Poole et al., 2004) but has remained controversial. This is because reactive oxygen species are generally perceived as indiscriminately reactive chemical entities, which would hinder the ability of ROS to achieve target/substrate specificity, a central aspect in cellular signaling.

In this review, we discuss the fundamentals of free radical biochemistry that underlie the potential of ROS to act as critical secondary messengers. We present evidence on the conflicting roles of ROS in promoting or suppressing tumorigenesis, discuss experimental caveats and misconceptions hindering our progress, and lastly, describe examples of current technological advances in areas of molecular imaging and biochemistry that should be more broadly utilized to increase our understanding of redox signaling. Our goal is to highlight the importance of defining specific redox-dependent vulnerabilities in cancer cells and to caution against the use of agents that lead to global redox changes as a strategy to target cancer cells.

Cellular Sources of ROS

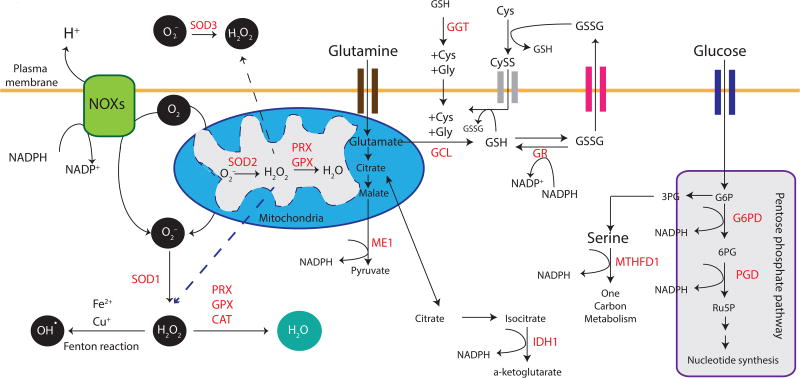

During normal cellular respiration in aerobic organisms, electrons are passed through a series of mitochondrial complexes to the terminal electron acceptor, molecular oxygen (O2). Leakage of electrons from the electron transport chain, primarily in reactions mediated by coenzyme Q, ubiquinone and its complexes, can produce O2− through the one-electron reduction of O2. Superoxide dismutases (SODs) are the major antioxidant defense systems against O2− (Fridovich, 1997). Accumulation of superoxides can damage proteins and lead to oxidative inactivation of nitric oxide, thereby leading to peroxynitrite formation and mitochondrial dysfunction (Radi et al., 1991). There are three isoforms of SODs in mammals: the cytoplasmic Cu/ZnSOD (SOD1), the mitochondrial MnSOD (SOD2), and the extracellular Cu/ZnSOD (SOD3), all of which require catalytic metal (Cu or Mn) for their activation (Inarrea et al., 2005). O2− released into the mitochondrial matrix by complexes I, II and III is rapidly converted into hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) by SOD2 (Murphy, 2009). O2− released from complex III into the intermembrane space traverses through voltage-dependent anion channels into the cytosol to be converted into H2O2 by SOD1 (Han et al., 2003; Muller et al., 2004). Mammalian SOD1 can also detoxify O2− in the mitochondrial intermembrane space to produce freely diffusible H2O2 (Inarrea et al., 2005; Sturtz et al., 2001). SOD3, a secreted extracellular Cu/Zn-containing SOD, is the major SOD in the vascular extracellular space that functions to protect against the toxic effects of superoxides (Stralin et al., 1995). The primary location of mammalian SOD3 in tissues is within the extracellular matrix and on cell surfaces, with a smaller fraction in the plasma and extracellular fluids (Marklund, 1984) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Sources of Cellular Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Defense Mechanisms.

The major source of cellular ROS is the mitochondria. Leakage through the electron transport chain releases mitochondrial superoxides (O2−), which can be converted by mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (SOD2) into hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Likewise, activity of oxidases such as NADPH oxidases (NOXs) at membranes, cytochrome p450 at the endoplasmic reticulum, lipoxygenases, cyclooxygenase and xanthine oxidase, can all lead to the production of O2, which can be converted by cytoplasmic SOD1 into H2O2. SOD3 mediates a similar reaction in the extracellular space. H2O2 can further undergo a Fenton chemical reaction to yield hydroxyl radicals (OH•). Peroxiredoxin (PRX), glutathione peroxidase (GPX) and catalase (CAT) enzymatically mediate reduction of H2O2 into water (H2O). A number of metabolic enzymes generate reducing equivalents of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) as a byproduct, thus contributing to the maintenance of redox homeostasis. Examples of these include Glucose-6-phosphate Dehydrogenase (G6PD) and 6-Phosphogluconate Dehydrogenase (PGD) of the Pentose phosphate pathway, Methylenetetrahydrofolate Dehydrogenase (MTHFD1), Isocitrate Dehydrogenase (cytoplasmic IDH1 and mitochondrial IDH2) and Malic Enzyme (cytoplasmic ME1 and mitochondrial ME2/3). Biosynthesis of reduced glutathione (GSH) is mediated through Glutamate-cysteine Ligase (GCL) while Glutathione Reductase (GR) catalyzes the reduction of glutathione disulfide (GSSG) back to the sulfhydryl form GSH. GSSG can be exported out of the cell through multidrug resistant proteins to maintain intracellular redox homeostasis. The oxidized dimer of cysteine, cystine, is a substrate for the cystine-glutamate antiporter (system xc–). This transport system increases the concentration of cystine inside the cell, which is quickly reduced to cysteine. Extracellular GSH can be hydrolyzed by Gamma-glutamyl Transferase (GGT) to yield products that are imported into cells as individual amino acids or as dipeptides. This salvage pathway represents a means by which GSH can be produced independently of GCL over the short term. Dotted lines denote H2O2 diffusion.

In addition to mitochondrial respiration, another prominent source of superoxides is the membrane-bound NADPH oxidase (NOX) complex, which mediates the catalytic generation of ROS. NOXs catalyze the generation of intracellular and extracellular O2− from O2 and NADPH (Bedard and Krause, 2007) (Figure 1). Although primarily localized to the plasma membrane, mammalian NOXs can be found on other membranes, including those of the nucleus, mitochondria, and endoplasmic reticulum (Bedard and Krause, 2007). Given their cellular localization, SODs 1 and 3 can rapidly convert NOX-derived O2− into H2O2, which can readily diffuse across membranes (Fisher, 2009). In the presence of a metal catalyst, H2O2 is converted to hydroxyl radicals (HO•) through the Fenton chemical reaction (Lloyd et al., 1997) (Figure 1). HO• is highly toxic due to its indiscriminate reactivity, leading to the oxidation of lipids, proteins and nucleic acids; their subsequent accumulation results in cellular damage or genomic instability (Dizdaroglu and Jaruga, 2012).

The unique chemical properties and compartmentalization of each reactive species as described above imply that alterations in the levels of each ROS type will incur different functional consequences in the cell. As such, it is essential to comprehensively define the reactive species in question when studying the role of redox homeostasis in both physiological and pathological settings. This point will be revisited in later parts of this review.

Achieving Balance—Antioxidant Defense Mechanisms

To protect macromolecules from indiscriminate damage incurred by free radicals, cells orchestrate a complex network of antioxidants to maintain proper cellular function. As described earlier, SODs are expressed in various cellular compartments and rapidly convert O2− into H2O2 in an effort to prevent O2−-induced inactivation of proteins in both unicellular and multicellular organisms (Chen et al., 2009b; Fridovich, 1997). To counter the effects of H2O2, Peroxiredoxins (PRXs), Glutathione Peroxidases (GPXs), and Catalase (CAT) convert intracellular H2O2 into water (Figure 1). Of these, PRXs are thought to be ideal H2O2 scavengers, given their abundant expression and broad distribution of 6 isoforms across the mammalian cell in the cytosol, mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum and the peroxisome (Rhee et al., 2012). Oxidized PRXs are subsequently reduced by Thioredoxins (TRXs), which are then restored to their reduced form by Thioredoxin Reductase (TR) and the reducing equivalent, Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate (NADPH) (Berndt et al., 2007). Hyper-oxidation of eukaryotic PRXs by a second H2O2 molecule into sulfinic acid can also be reactivated by the enzymatic activity of sulfiredoxin (Biteau et al., 2003; Woo et al., 2003) (Figure 2). In addition to PRXs, the GPX family of proteins (GPX1-8) can also convert H2O2 to H2O in the cytoplasm and mitochondria. During this process, GPXs oxidize reduced glutathione (GSH) to glutathione disulfide (GSSG). Analogous to TR, Glutathione Reductase (GR) reduces oxidized GSSG back to GSH, using NADPH as an electron donor (Couto et al., 2016). In the peroxisome, CAT efficiently converts H2O2 to H2O in the absence of any cofactors.

Figure 2. Oxidative Modifications of the Amino Acid Cysteine.

Top: Reactive cysteine thiols (R-SH) can be oxidized by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), organic hydroperoxides, hypohalous acids or peroxynitrite to form sulfenic acids, which can go on to form reversible disulfides (R-SS-R') or irreversible oxidation products such as sulfinic acid or sulfonic acids. Sulfinic acid forms of some peroxiredoxins can be enzymatically recovered through the action of sulfinic acid reductases (sulfiredoxins).: Bottom: Disulfide reduction by the dithiol reductant thioredoxin (TRX) or glutaredoxin (GRX). Two electrons are required in a two-step reaction to reduce the two proximal cysteines from the disulfide to the dithiol form. Reduction of a regulatory disulfide by TRX or GRX creates an unstable intermediate mixed disulfide form. The close proximity of a second cysteine in these dithiol reductases drives the forward reaction to reduce the disulfide into the dithiol form with high efficiency. (For a detailed discussion of cysteine-based modifications please refer to (Klomsiri et al., 2011)).

NADPH is an important cofactor for replenishing reduced GSH (Mannervik, 1987) and TRX pools (Holmgren and Lu, 2010). There are multiple sources of NADPH as an enzymatic byproduct in both the cytosol and the mitochondria of mammals. These include glucose 6 phosphate dehydrogenase, an enzyme that shunts glycolysis to the oxidative arm of the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP); isocitrate dehydrogenases (IDH1 and 2), which catalyze the oxidative decarboxylation of isocitrate; and malic enzymes (ME1, 2 and 3), which catalyze the oxidative decarboxylation of malate to pyruvate (Minard et al., 1998). In the pathway of one-carbon metabolism, carbon units from serine and glycine amino acids feed into the folate cycle, which is essential for nucleotide synthesis (Locasale, 2013) and is an important source of NADPH in the cytosol and mitochondria (Fan et al., 2014; Lewis et al., 2014) (Figure 1).

The activity and production of the above enzymatic antioxidants and reducing equivalents is tightly regulated by a number of key transcription factors. Nuclear Factor, Erythroid 2 like 2 (NFE2L2/NRF2) is a master regulator of redox homeostasis in response to oxidative stress and is activated by cells to increase the expression of gene networks involved in cytoprotective activities. This includes xenobiotic metabolism (Higgins and Hayes, 2011), regulation of proteasomal subunits (Kapeta et al., 2010; Kwak et al., 2003) and inflammatory responses (Meakin et al., 2014). Cellular levels of NRF2 are primarily controlled post-translationally (Hayes and Dinkova-Kostova, 2014), although oncogene-induced transcription has also been described in KrasG12D-expressing murine embryonic fibroblasts (DeNicola et al., 2011) and pancreatic ductal cells (Chio et al., 2016). In both murine and human cells, NRF2 is a short-lived protein under basal conditions, as it is targeted for proteasomal degradation through its interaction with the cytoplasmic protein Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1) and the CULLIN 3/Ring-Box1 (CUL3-/RBX1) ubiquitin ligase complex (Ishii et al., 2000; Itoh et al., 1999; Kobayashi and Yamamoto, 2006). When levels of H2O2 are high, redox-sensitive cysteine residues in KEAP1 can undergo oxidation, thus preventing NRF2 association and subsequent degradation in both murine (Zhang and Hannink, 2003) and human (Fourquet et al., 2010) cells. In the absence of Keap1, the β-TRCP/GSK-3 axis can also mediate degradation of Nrf2 in murine embryonic fibroblasts (Rada et al., 2011) through recognition motifs in the Neh6 domain of murine or human NRF2 (Chowdhry et al., 2013). Stabilized NRF2 translocates into the nucleus to induce the expression of antioxidants such as GPXs, PRXs and CAT, as well as enzymes involved in GSH synthesis and utilization (Jaramillo and Zhang, 2013). Furthermore, NRF2 activation has also been shown to promote NADPH production by regulating enzymes in the pentose phosphate and serine biosynthesis pathways in both murine (Wu et al., 2011) and human (DeNicola et al., 2015; Mitsuishi et al., 2012) cells.

In addition to NRF2, the transcription factor p53 has also been shown to suppress ROS accumulation by directly regulating the expression of a variety of antioxidant genes including SOD2, GPX1 and CAT (Budanov et al., 2004; Kruiswijk et al., 2015), and indirectly through the induction of the metabolic gene TP53-inducible glycolysis and apoptosis regulator (TIGAR) (Bensaad et al., 2006; Cheung et al., 2012). Expression of TIGAR suppresses levels of fructose 2-6-bisphosphate, redirecting glucose carbons to the PPP and increasing cytosolic NADPH production to suppress ROS accumulation in cell culture (Yin et al., 2012). As discussed in subsequent sections, alterations in the expression or activity of any of the above oxidant-producing or -suppressing enzymes, contribute directly to the process of tumorigenesis, underscoring the importance of redox homeostasis in tumor development.

The ROS Conundrum—A Friend or a Foe?

Changes in cellular redox states have long been implicated in a variety of diseases (Andersen, 2004; Cross et al., 1987; Mugge, 1998; Paravicini and Touyz, 2006), and its role in tumorigenesis has remained an area of major interest. Much of the early excitement stemmed from clinical data obtained by Linus Pauling, where he demonstrated that intravenous administration of vitamin C in terminal human cancer patients resulted in clinical benefit (Cameron and Pauling, 1976, 1978). This laid the foundation for the concept that elevated ROS was conducive to tumorigenesis and thus, suppression through antioxidants could be prophylactic, if not therapeutic. Subsequent studies using monolayer, immortalized cell lines demonstrated that ectopic expression of oncogenes could lead to enhanced ROS generation when compared to immortalized, non-transformed counterparts (Szatrowski and Nathan, 1991), further lending support to the notion that ROS could promote tumorigenesis. High levels of ROS can cause damage to nucleic acids, which has led to the hypothesis that elevated ROS can be carcinogenic by serving as a mutagen and promoting genomic instability (Ames et al., 1993). Over the past decade, contradictory evidence has emerged regarding the role of ROS in tumorigenesis. While ROS have been shown to promote cancer cell proliferation, survival, angiogenesis and metastasis in mouse models and human cell lines (Sabharwal and Schumacker, 2014), experimental studies have revealed that dietary supplementation of the antioxidants N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) or Vitamin E markedly accelerated tumor development and mortality in mouse models of oncogenic Kras- and Braf-induced lung cancer (Sayin et al., 2014). Additionally, metastasis was promoted by NAC in melanoma human xenografts (Piskounova et al., 2015). Similar results were obtained in an endogenous oncogenic Braf/PTEN null mouse model of melanoma, where NAC and Trolox increased the rate of melanoma cell migration and invasion without impacting the growth of primary tumors (Le Gal et al., 2015). Furthermore, dietary supplementation of folate, a cofactor of one-carbon metabolism for the production of NADPH, has also been shown to promote the development and progression of breast cancer in experimental murine models (Deghan Manshadi et al., 2014; Ebbing et al., 2009). Finally, clinical trials revealed that supplementation with the antioxidants beta-carotene, NAC, vitamin A or E did not reduce the incidence of head and neck, lung, colorectal or prostate cancers (Fortmann et al., 2013; van Zandwijk et al., 2000). Instead, these treatments were shown to increase the incidence and mortality from lung and prostate cancer (Goodman et al., 2004; Klein et al., 2011).

In an attempt to reconcile these seemingly contradictory observations, major findings supporting the tumor promoting or tumor suppressive role of ROS are reviewed herein, followed by a discussion of the potential caveats in experimental design and interpretations of these studies that in part, have fostered this controversy.

ROS Promote Tumorigenesis

Tumor Promoting Genetic Alterations Generate ROS

Studies beginning in the 90s set the stage for the concept that ROS is a driving factor for tumorigenesis. Notably, overexpression of human SODs in murine sarcoma cells have been shown to suppress radiation (but not chemical) induced transformation and thus metastasis (Safford et al., 1994; St Clair et al., 1992). Ectopic expression of oncogenic Ras was observed to induce the production of ROS, measured as superoxides, and led to enhanced proliferation of immortalized human fibroblasts (Irani et al., 1997; Ogrunc et al., 2014; Sohn and Rudolph, 2003; Yang et al., 1999). However, observations of elevated ROS following ectopic oncogenic Ras expression were not present in cells where oncogenic Ras was expressed at the endogenous locus, and are thus likely artifactual (DeNicola 2011). Loss of the tumor suppressor p53, either in human cancer cell lines through siRNA-mediated knockdown (KD), or in primary splenocytes and thymocytes from Trp53 knockout (KO) mice, has been shown to elevate ROS production (Sablina et al., 2005). Strikingly, pre-partum administration of NAC in drinking water extended life and blunted lymphoma formation in p53-deficient murine offspring (Sablina et al., 2005). Additionally, Trp53 mutant mice that are incapable of cell cycle arrest, senescence and apoptosis -- through lysine to arginine mutations at three of the critical p53 acetylation sites (K117, 161, 162) -- were found to be resistant to early onset spontaneous tumorigenesis (Li et al., 2012). Since these mice retain intact regulatory mechanisms for energy metabolism and ROS production, p53-dependent redox regulation was predicted to be a critical aspect of p53-mediated tumor suppression (Li et al., 2012). Similar to p53, the ability of other transcription factors to regulate the intracellular redox environment is considered to constitute a critical aspect of their tumor suppressive functions. These include the FOXO family of proteins, activation of which leads to the up-regulation of antioxidant enzymes such as MnSOD and catalase (Greer and Brunet, 2008). Likewise, genetic ablation of Brca1 increased ROS levels and the frequency of spontaneous mammary tumor formation in p53 heterozygous mice (Cao et al., 2007). A recent report suggests that BRCA1-dependent regulation of oxidative stress is mediated through NRF2 (Gorrini et al., 2013).

Elevated ROS through the above genetic alterations is believed to drive tumorigenesis in part by acting as a direct DNA mutagen (Irani et al., 1997; Ogrunc et al., 2014; Sohn and Rudolph, 2003; Yang et al., 1999) or via induction of genomic instability upon activation of topoisomerase II (Shibutani et al., 1991). These observations support the notion that ROS induced mutagenesis is a critical driving factor of tumor initiation and progression.

ROS Promote Cell Migration

Loss of cell-to-cell adhesion, survival upon matrix detachment, migratory ability and breakthrough into the cell basement membrane are all critical features of tumor metastasis, and ROS have been implicated in these processes (Chiang and Massague, 2008). For instance, in Src-transformed 3T3 fibroblasts, NOX-derived ROS were shown to promote the formation of invadopodia in vitro (actin-rich protrusions of the plasma membrane) (Diaz et al., 2009). In this study, treatment of cells with NAC or DPI (diphenyleneiodonium chloride)—a flavoprotein inhibitor of the NOX family of NADPH oxidases—prevented lamellipodia formation (thin-sheet membrane protrusions of motile cells). Similarly, sustained activation of 5-lipoxygenase in human metastatic prostate cancer cells could lead to elevated production of ROS and oxidative activation of vSrc (Giannoni et al., 2009); this in turn, enhanced invasive potential, anchorage-and growth factor independent-growth of Src-transformed cells in vitro. Accordingly, these effects were suppressed upon NAC supplementation in the media (Giannoni et al., 2009).

In addition to cytosol-derived ROS, mitochondrial ROS have been shown to support Kras-induced anchorage-independent growth of murine lung cancer cells through dampening the MAPK/ERK pathway (Weinberg et al., 2010). Likewise, elevated ROS levels resulting from mutations in mitochondrial DNA (impairing complex I activity) were also reported to promote the migration and engraftment of mouse and human tumor cell lines in the lung upon tail vein injection (Ishikawa et al., 2008). This process was suppressed when cells were treated with NAC prior to tail vein injection into mice that were further supplemented with NAC through their drinking water. The notion that ROS enable tumor cell migration and metastasis has been further supported by recent observations that SOD3 is epigenetically silenced in breast cancer. Specifically, intramuscular injection of adenovirus-expressing SOD3 into mammary-tumor bearing mice followed by primary tumor resection was shown to reduce cancer metastasis to the lung (Teoh-Fitzgerald et al., 2014). This suggests that in addition to intracellular redox homeostasis, restoration of the extracellular superoxide scavenging activity can contribute to mammary tumorigenesis. Finally, administration of the mitochondrially-targeted superoxide scavenger, MitoTEMPO, has been shown to block the establishment of lung metastases by tail vein-injected B16 murine melanoma cells or MDA231 human breast cancer cells (Porporato et al., 2014). Collectively, these observations support the hypothesis that intracellular and extracellular ROS fuel migratory processes that are central to cancer metastasis.

ROS Drive Mitogenic Signaling Cascades

Growth factor activation has been shown to induce sustained H2O2-dependent stimulation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and MAPK/ERK signaling cascades. This is believed to be mediated through oxidative inactivation of phosphatases such as the phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) (Lee et al., 2002), protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) 1B (Salmeen et al., 2003) and MAPK phosphatases (Son et al., 2011), which are all negative regulators of the PI3K/AKT and MAPK pathways. Given the importance of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR (Liu et al., 2009) and MAPK/ERK (Roberts and Der, 2007) pathways in growth and survival, hyper-activation of these pathways is a hallmark of a number of solid and hematological malignancies. Indeed, genetic studies demonstrated that loss of the antioxidant enzyme Prx1 promoted mammary tumorigenesis in MMTV/v-H-Ras expressing mice through H2O2-dependent increase in AKT activity (Cao et al., 2009). Loss of Prx1 further predisposed mice to spontaneous malignancies such as lymphomas, sarcomas and carcinomas upon aging (Neumann et al., 2003). Thus, ROS is believed to be tumor-promoting through activation of the above mitogenic signaling pathways.

Antioxidants Promote Tumorigenesis

Tumor-Promoting Genetic Alterations Induce Endogenous Antioxidants

As discussed earlier, NRF2 is essential for the transactivation of a battery of genes involved in the maintenance of redox homeostasis (Hayes and Dinkova-Kostova, 2014). Constitutive up-regulation of this transcription factor has been reported for a variety of human cancer types including skin, breast, prostate, lung and the pancreas (No et al., 2014). Experimentally, NRF2 activity has been demonstrated to be essential for cancer cell proliferation (DeNicola 2011, Chio 2016) metabolic reprogramming (Mitsuishi et al., 2012), chemoresistance (Zhang et al., 2010), serine biosynthesis (DeNicola et al., 2015), as well as mRNA translation (Chio et al., 2016), in part through maintenance of redox homeostasis. More specifically, a downstream target gene of NRF2, xCT/SLC7a11, the light subunit of the system xc– essential for the import of cysteine to support GSH synthesis, has been implicated in the proliferation and multidrug resistance of several types of cancer cells, including lung and ovary malignancies (Chen et al., 2009a; Huang et al., 2005; Lo et al., 2008). Pharmacological inhibition of xCT has been shown to markedly inhibit the growth of a variety of carcinomas, including hepatocellular carcinoma (Guo et al., 2011), lymphoma (Gout et al., 2001), glioma (Chung et al., 2005), prostate (Doxsee et al., 2007) and breast cancer (Narang et al., 2003). Overexpression of SLC7A11 in human breast and liver cancer cells abrogates p53 (3KR)-mediated tumor growth suppression in xenograft models through maintenance of their antioxidant capacity and ability to evade ferroptosis (Jiang et al., 2015).

In line with the above observations, in experimental mouse models elevated intracellular levels of GSH have been found to be necessary for the initiation and progression of cancers of various origins: pancreatic (Chio et al., 2016; DeNicola et al., 2011), mammary (Harris et al., 2015) and lung (Sayin et al., 2014). Loss of TIGAR -- a gene controlling glucose metabolism to maintain NADPH levels to regenerate GSH -- can impair both proliferation and survival of human cancer cell lines following oxidative or genotoxic stress (Bensaad et al., 2006; Lui et al., 2011; Wanka et al., 2012; Yin et al., 2012). Gut-specific genetic ablation of Tigar in mice was reported to restrict hyper-proliferation seen in Wnt-driven adenomas by failing to limit ROS production (Cheung et al., 2013). These studies support the notion that endogenous antioxidants are essential in the process of tumorigenesis.

Endogenous Antioxidants Promote Cell Migration and Metastasis

As tumor cells detach from the extracellular matrix and invade the basement membrane, ROS levels increase and the reduced pool of GSH decreases (Schafer et al., 2009). In contrast to the reported roles of ROS in promoting cell migration (see previous section), NADPH-generating enzymes of the folate-mediated one-carbon metabolism pathway have been shown to promote distant metastasis in human melanoma cells (Piskounova et al., 2015). In this study, administration of NAC was reported to increase the frequency of melanoma cells in the blood and metastatic disease burden. This is in line with observations that epithelial cells undergo cell death upon matrix detachment in culture due to reduced glucose uptake, ATP depletion and elevated oxidative stress (Debnath and Brugge, 2005; Debnath et al., 2002). Furthermore, breast and lung cancer cell lines undergo metabolic changes to suppress ROS during invasion in culture, and metastasis in vivo (Chen et al., 2007; Dey et al., 2015; Dong et al., 2013; Kamarajugadda et al., 2013; Lu et al., 2010; Qu et al., 2011). Also, oncogenic signaling promotes survival of matrix-detached cells through increased glucose uptake and flux through the pentose phosphate pathway to generate reducing equivalents of NADPH (Schafer et al., 2009). Lastly, treatment of these cells with the antioxidants NAC or Trolox can substantially increase the number and average size of colonies, indicating a role of antioxidants in enhancing the transforming activity of cells that experience oncogenic insults. In congruence with the above findings, cytosolic IDH1-dependent reductive carboxylation also promotes anchorage-independent growth by increasing the abundance of mitochondrial NADPH (Jiang et al., 2016). Thus, an increase in intracellular reducing equivalents through metabolic changes is in favor of supporting cancer cell growth, survival and migration.

ROS Activate Stress-Induced Signaling Pathways to Trigger Cell Death

In contrast with its ability to activate mitogenic signaling pathways, elevated levels of ROS have also been shown to induce cell cycle arrest, senescence and cancer cell death through the activation of the ASK1/JNK and ASK1/p38 signaling pathways in human fibroblasts and cancer cells (Ichijo et al., 1997; Moon et al., 2010). This is believed to be mediated by H2O2 oxidation of TRX1 and subsequent dissociation of ASK1, thereby triggering the suppression of anti-apoptotic factors through sustained activation of the downstream MAP kinase kinase (MKK)4/MKK7/JNK and MKK3/MKK6/p38 pathways (Ichijo et al., 1997; Saitoh et al., 1998; Thornton and Rincon, 2009; Tobiume et al., 2001; Wagner and Nebreda, 2009). Additionally, ROS have been shown to mediate death receptor activation through down-regulation of the cytoprotective FLIP protein (Wang et al., 2008). More recently, oxidizing agents such as buthionine sulfoximine have been shown to functionally inactivate mitogenic signaling cascades driven by AKT in pancreatic ductal cells (Chio et al., 2016) as well as in skeletal muscle cells (Tan et al., 2015). Collectively, these observations support a tumor-suppressive role of ROS and highlight the importance of endogenous antioxidants in promoting cancer cell growth and survival.

What Is the Source of Contention?

As outlined above, there is abundant evidence advocating for either a supportive or a suppressive role of ROS in the process of tumorigenesis. This accentuates two facts, i) redox regulation is of indisputable importance in the etiology and progression of cancer and ii) our understanding of thiol redox dynamics in cells and organisms is still at its infancy. As we begin to dissect the diverse and complex outcomes of cellular redox changes, we should also be wary of the following experimental and conceptual caveats that might have contributed to the current controversies.

N-Acetylcysteine—More than an Antioxidant

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is an important antioxidant because it augments the synthesis of GSH. NAC readily enters cells and within the cytosol, it is converted to L-cysteine, which is a precursor to GSH. NAC is also a source of sulfhydryl groups in cells and scavenger of free radicals as it interacts with ROS such as OH• and H2O2 (Aruoma et al., 1989). For this reason, NAC is broadly referred to in the literature as the rescue agent for systems under oxidative stress. However, there are numerous pleiotropic effects associated with NAC that are often under appreciated. At low doses (0.1–1 mM), NAC works as a regulator of redox state, but at elevated doses (>5 mM), it can directly alter the structure of TGF-beta (White et al., 1999) and can induce p53-dependent apoptosis selectively in oncogenically transformed cells, an activity that is not observed in chain-breaking antioxidants such as vitamin E and Trolox (Liu et al., 1998). Importantly, an increase in GSH is not required for apoptosis-triggered NAC. It has been shown that treatment of human breast cancer cells with NAC suppresses the activation of NRF2 target genes in the presence of ROS-inducing agents such as tert-butyl hydroquinone (Wang et al., 2006). While this may be due to NAC-mediated augmentation of GSH, it also raises the possibility that antioxidant defense mechanisms may be blocked through alternative means by the presence of NAC. Therefore, the experimental use of NAC at high doses should be interpreted with caution.

Is it Metabolism, Redox, or Both?

NADPH provides the reducing equivalents for the regeneration of GSH. Two major contributors of cytosolic reducing equivalents of NADPH are the pentose phosphate pathway and the serine one-carbon metabolism (folate cycle). Other generators of NADPH include ME1, IDH1/2 and NNT. Elevated activities of these enzymes and pathways are generally thought to support the notion that increased reducing equivalents promote the growth, survival and migration of cancer cells (Cairns et al., 2011). However, in addition to being a major reducing equivalent, NADPH is also used for anabolic pathways, such as lipid synthesis, cholesterol synthesis and fatty acid chain elongation. In fact, in a recent study, deuterium labeling of NADPH revealed that the overall demand for NADPH for biosynthesis is greater than 80% of total cytosolic NADPH production, with most of this NADPH consumed for fatty acid synthesis (Ye et al., 2014). Consequently, in transformed cells growing under aerobic conditions, the majority of cytosolic NADPH is actually devoted to biosynthesis and not to redox defense. In other words, an increase in the demand for NADPH-producing enzymes in cancer cells may not necessarily reflect an increase in redox sustenance but rather, an increase in anabolic demands.

The relationship between mitochondrial metabolism and ROS is also confounded by the ambiguity of conventional methods for assigning ROS production to individual mitochondrial sites. Indeed, alterations in cancer cell mitochondrial activity will inevitably lead to changes in both cellular metabolism and redox status. For example, pharmacological inhibition of complex III of the electron transport chain (ETC) in human cancer cells supports the idea that ROS, generated from complex III, are required for hypoxia-dependent HIF1 stabilization (Brunelle et al., 2005; Guzy et al., 2005; Mansfield et al., 2005). This is proposed to be the consequence of direct inhibition of prolyl hydroxylase (PHD) enzymes through oxidation of essential non-heme-bound iron (Pan et al., 2007). However, most pharmacological and genetic interventions altering the function of the ETC induce changes in both oxygen consumption and mitochondrial ROS production (Chua et al., 2010); it is thus challenging to distinguish the difference between mitochondria-dependent regulation of HIF1 proline hydroxylation via the depletion of oxygen or the increase in reactive oxygen. Likewise, the inability to modulate ROS production without altering ATP synthesis poses a major obstacle in our comprehension of the physiological roles of specific mitochondrial sites of ROS production. For this reason, experimental evidence for the contribution of ROS to the process of tumorigenesis remains difficult to interpret because methods for altering mitochondrial superoxide or peroxide production also change energy metabolism. Approaches to manipulating each parameter independently will be critical to establishing a definitive mechanism. Accordingly, a recent high-throughput screen of 65,000 small molecules against mitochondrial H2O2 production revealed that compounds such as S3QEL, specifically suppressed complex III O2− production without impairing the bioenergetic function of mitochondria (Orr et al., 2015). By experimentally facilitating the dissociation of energy metabolism from mitochondrial ROS production, approaches using compounds such as these may help address a longstanding problem in redox biology—do mitochondrial changes contribute more to metabolic alterations, redox regulation, or both? Addressing this issue will hold promise for a better understanding of the role of redox alterations in cancer initiation and progression.

ROS Harbor Multiple Signaling Entities with Diverse Spatiotemporal Functions

Many questions regarding the role of ROS in tumorigenesis still remain, largely stemming from the seemingly opposing roles of ROS, which on the one hand, can suppress cell growth through genotoxic stress and protein translational arrest; and on the other hand, can promote cell growth through activation of mitogenic signaling cascades. The role of ROS in cellular outcome is clearly more diverse than anticipated. Cellular responses to ROS reflect a complex integration of ROS type, location and levels. For example, mitochondrial ROS are reportedly central to promoting damage and death (Abramov et al., 2007; Adam-Vizi and Chinopoulos, 2006; Giulivi et al., 1995; Heales et al., 1999), while membrane generated ROS are more often described as contributing to proliferation, tumorigenicity, migration, and metastasis (Choi et al., 2005; Li et al., 2006; Ushio-Fukai, 2006; Vilhardt and van Deurs, 2004). However, these distinctions are not absolute, because mitochondrial ROS have also been shown to contribute to proliferation, tumorigenicity, migration and metastasis (Kwon et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2002; Porporato et al., 2014; Weinberg et al., 2010), while NOX-generated ROS at the membrane can also induce cell death via ferroptopsis and necrosis (Dixon et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2007). In this context, oxidized lipids at the membrane have also been to show to exhibit a variety of functions. For example, oxidized low density lipoprotein can induce cellular apoptosis in murine vascular smooth muscle cells (Hsieh et al., 2001) or activation of nfkb in bovine endothelial cells (Cominacini et al., 2000). The cell-compartmentalization of ROS functions is further exemplified by a recent study where inhibitors of mitochondrial ROS (mitoTEMPO, LAME, Allopurinol) increased proliferation in Tigar-deficient Adenomatous polyposis coli (Apc) mutant murine intestinal organoids (from ApcMin mutant mice), whereas inhibitors of NOX (DPI, ML171) inhibited proliferation (Cheung et al., 2016).

Collectively, these observations underline what may be the major conceptual and experimental limitation in the field of cancer redox biology; that is, our tendency to focus on the global effect of ROS as one single biochemical entity operating in a binary fashion. Indeed, ROS involvement in cancer is not confined to indiscriminate macromolecular damage. The regulation of ROS is both topological and temporal (Chandel and Tuveson, 2014). More importantly, ROS function as intracellular secondary messengers, with each reactive species temporally and spatially orchestrating unique signaling events much like kinases, ubiquitylases and acetyltransferases, among others. However, unlike these more familiar signaling events, target specificity in redox signaling occurs at the atomic level and not at the macromolecular level. Given this, the potential number of ROS-specific effectors is predicted to be massive and underexplored. Much like kinase signaling, the output of redox signaling is the integration of mechanisms governing the source, specificity and functional consequence of each oxidative post-translational modification. Since total phosphate levels cannot be used as a metric to decipher the biological consequence of kinase signaling events, standard approaches to quantify relative changes in global levels of ROS should not be expected to adequately reveal the biological consequence of specific redox signaling events. New techniques to better monitor the activity of specific redox couples with appropriate spatiotemporal resolution will be essential to defining the source and kinetics of redox signaling, which will be fundamental to resolving the ROS conundrum.

Advancing Forward: Strategies to Defining ROS

ROS have distinct intrinsic chemical properties including reactivity, half-life and lipid solubility, distinguishing them from other signaling molecules (Halliwell and Gutteridge, 1986), and allowing them to react with preferred biological targets. O2− exhibits high atomic reactivity with iron-sulfur (Fe-S) clusters at a rate that is almost diffusion-limited, releasing iron in the process of oxidation. Although O2− can also react with thiols in a cell-free system, the reaction occurs at a rate that is too low to be relevant intracellularly (Winterbourn and Metodiewa, 1999). The stability of O2− is also relatively low; and in conjunction with its inability to diffuse through membranes due to its negative charge, these properties render superoxide a poor signaling molecule (Halliwell and Gutteridge, 1986). By contrast, H2O2 is a relatively poor oxidant reacting mildly with Fe-S, and very slowly with glutathione and free cysteines (Winterbourn and Metodiewa, 1999). However, its reactivity towards cysteine residues in proteins can substantially vary depending upon the protein chemical environment (Poole, 2015). Moreover, H2O2 is relatively stable and diffuses readily through membranes or transport through aquaporins. These properties render H2O2 highly suitable for signaling (Bienert et al., 2006).

The best-described mechanism of redox signaling involves H2O2-mediated oxidation of cysteine residues within proteins (Rhee, 2006), which constitutes the main regulatory target of H2O2. The sulfur atom on cysteines can cycle between two oxidation states; oxidation of the free thiol leads to the formation of a sulfenic acid residue, which can either return to its native state through reduction by glutathione, or react with a neighboring free thiol to form a disulfide bond. Further oxidation will lead to the formation of sulfinic or sulfonic acids, which are irreversible modifications that will break the redox switch (Poole et al., 2004) (Figure 2). Importantly, cysteine residues are not equal in their ability to undergo the above redox modifications (Gilbert, 1990; Poole et al., 2004), providing a basis for selectivity and specificity. And, selective reactivity appears to be the reason why the cysteine residue is not a target of H2O2 toxicity. This is further supported by proteome-wide studies showing that H2O2 does not cause random protein thiol oxidation (Chio et al., 2016; Le Moan et al., 2006).

Analogous to other forms of protein post-translational modifications, covalent, oxidative modifications on cysteines represent a viable approach to transform an oxidant signal to cellular outcomes. Oxidative cysteine modifications are central to redox regulation of protein function but the impact of this transient post-translational modification remains under-explored, particularly in the context of cancer. The reversible nature of cysteine sulfenic acid, disulfide and S-glutathionylation render them as potential binary switches to mediate the crosstalk between mechanisms of redox control and signaling pathways. With the discovery of sulfiredoxin proteins (Srx) in mammals and yeast, which can reduce hyper-oxidized sulfinic acids on peroxiredoxins (Biteau et al., 2003; Chang et al., 2004), cysteine sulfinic acids have also emerged as a potential regulatory mechanism to reversibly regulate the activity of other proteins. The impact of oxidative cysteine modification is diverse. For example, while S-glutathionylation of certain enzymes such as fructose 1,6-bisphosphate can induce their enzymatic activity (Nakashima et al., 1970), but the same modification on other enzymes such as the cysteine protease caspase 3 (Huang et al., 2008) leads to functional inactivation. Oxidative modifications of cysteines in non-enzymatic sites have also been reported, influencing protein-DNA or protein-protein interactions. For instance, oxidation of cysteines at the dimer interface of p53 inhibits p53-DNA interaction in human cells (Velu et al., 2007). The diversity of redox-dependent events parallels that of kinase signaling and necessitates the use of biochemical approaches to detect cysteine oxidative changes with chemical specificity. Systematic identification followed by functional analysis of redox-sensitive proteins during different stages of tumorigenesis constitutes the first step in defining the role of ROS in cancer development.

Molecular Tools to Map and Quantify Oxidative Cysteine Modifications in Cancer Cells

Considerable effort has been placed into developing methods to study changes in post-translational oxidative modifications of cysteines. These include indirect methods to detect cysteine oxidation following loss of reactivity with thiol-modifying agents such as N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) or iodoacetamide (IAM) (Hill et al., 2009; Ying et al., 2007). To directly detect distinct oxidative cysteine modifications, small molecule and protein-based approaches have also been developed. This includes the OxICAT method to detect disulfides (Leichert et al., 2008) and biotinylated GSH ethyl ester (Eaton et al., 2002; Sullivan et al., 2000) or N,N-biotinyl glutathione disulfide (Brennan et al., 2006) to monitor protein S-glutathionylation in lysates, isolated cells and tissues. Unlike disulfides and S-glutathionylation, both of which are relatively stable modifications, sulfenic acids are highly reactive and are often deemed as labile intermediates en route to additional cysteine modifications. For this reason, sulfenic acid analysis has remained challenging. Emerging methods for sulfenic acid detection include the use of azido and alkyne-functionalized dimedone analogs such as DYn-2 (Paulsen et al., 2011) to trap and tag protein sulfenic acid modifications directly in living cells. The use of isotopically light and heavy derivatives of DYn-2 will further facilitate quantification of these modifications (Truong et al., 2011). Indeed, a chemoproteomics platform using DYn-2 to selectively label and detect protein S-sulfenylation accompanied with structural profiling revealed the presence of S-sulfenylated sites on the functional domains of protein kinases, phosphatases, acetyltransferases, deacetylases and deubiquitinases, highlighting the important regulatory crosstalk between redox signaling and other major post-translational modification events (Yang et al., 2014). In addition to chemical approaches, immunological methods to specifically detect protein sulfenic acid modifications and unrelated sulfinic or sulfonic acid modifications have been developed (Seo and Carroll, 2009). Similarly, immunological methods for the global proteomic assessment of the PTP redoxome that relies on perfomic acid hyperoxidation of cysteine oxyacids have also been reported (Karisch et al., 2011). With the advent of three-dimensional organoid models that support the ex-vivo culture and growth of normal, premalignant and malignant primary tissue (Cantrell and Kuo, 2015), these biochemical and immunological tools will provide a facile platform to interrogate the differences in sulfenic acid modifications in normal versus cancer cells. This will commence the identification of cancer-specific redox dependencies that may be therapeutically actionable. For readers interested in additional chemical proteomic strategies to study thiol redox modifications, please refer to a recent review from the Carroll laboratory (Yang et al., 2016).

Molecular Tools to Visualize Free Radicals In Space And Time

As critical secondary messengers in the cell, ROS-dependent signaling is expected to be regulated in a time- and space-dependent manner. Thus, to complement the above biochemical approaches to study target-specific consequences of redox signaling, development of redox-sensitive probes to track the dynamics of specific redox couples in real time will also be essential. Our knowledge of cysteine biochemistry has facilitated the development of tools in this regard. Redox sensitive yellow fluorescent protein (rxYFP) (Ostergaard et al., 2001) and green fluorescent protein (roGFP) (Dooley et al., 2004; Hanson et al., 2004) are developed by engineering each fluorescent protein to contain two cysteine residues that are present in adjacent beta-strands on the surface of the protein beta-barrel. As these cysteines are engineered in close proximity to the chromophore, oxidation-induced disulfide bond formation will bring about structural changes that will affect the protonation state of the chromophore, which is reflected by two clear excited maxima at 395nm (neutral) and 475nm (anionic). In other words, the redox state of the engineered thiol-disulfide pair is directly coupled to the relative intensity of the two fluorescence maxima, allowing for real time readout of the kinetic changes of the redox state of this thiol-disulfide pair (Meyer et al., 2007; Ostergaard et al., 2004; Schwarzlander et al., 2008).

To tailor these probes to specific redox couples, fusion probes have been generated. For example, genetic coupling of Grx1 to roGFP (Gutscher et al., 2008) increased the effective local concentration of Grx1 near roGFP by 3000 fold, thus leading to the specificity of these sensors to the glutathione redox couple. The development of the roGFP2-Orp1 H2O2 sensor (Gutscher et al., 2009) is based on the observation that redox relays exist between thiol peroxidases and specific target proteins (Delaunay et al., 2002; Sobotta et al., 2015). Thiol peroxidases, in this case, Orp1, rapidly react with H2O2, leading to the formation of a sulfenic acid and subsequently, a disulfide bond. By genetically fusing Orp1 to roGFP2, the oxidation state of Orp1 will be passed directly and preferentially to roGFP2 (as opposed to endogenous Trxs) through a thiol-disulfide exchange (Gutscher et al., 2009). As such, fluorescence emanating from the roGFP2 reporter will serve as a direct indication of cellular H2O2 levels.

In addition to providing dynamic information to specific redox couples, these probes can also be engineered such that they are targeted to specific cellular compartments to extract topological information about any redox change within the cell. Examples of this include the cytosol (Albrecht et al., 2011), mitochondria (Albrecht et al., 2011; Dooley et al., 2004), mitochondrial intermembrane space (Waypa et al., 2010), endoplasmic reticulum (van Lith et al., 2011), nucleus (Schnaubelt et al., 2015), and peroxisome (Rosenwasser et al., 2011). Application of these tools in plants, Drosophila and mammalian cell cultures have provided insights into the importance of specific pathways in redox balance, an endeavor that would be challenging using standard assays to measure net changes in global ROS levels. New insights that have been gained from the above redox sensors include the observation that GSH homeostasis in one subcellular compartment is unaffected by changes in another compartment (Hu et al., 2008; Kojer et al., 2012), even though GSSG can be transported between subcellular compartments such as the cytosol and the vacuole (Morgan et al., 2013). Consistently, the regulation of glutathione redox potentials and H2O2 levels in different cellular compartments are not always interdependent (Albrecht et al., 2011). These findings reveal that we are only beginning to understand the relationship between different redox species and cellular functions.

Recently, mouse models of redox sensors have emerged. A mouse line expressing a roGFP variant in the mitochondrial matrix was used to study Parkinson's disease (Goldberg et al., 2012; Guzman et al., 2010). Subsequently, cytosolic and mitochondrial roGFP1 lines were used for in vivo analysis of redox dynamics in mouse skin (Wolf et al., 2014). A mouse model expressing Grx1-roGFP2 in the mitochondrial matrix of neurons has also been established and used to study the redox physiology and pathology of axonal mitochondria of living mice (Breckwoldt et al., 2014). Application of these redox sensitive probes in different genetically engineered mouse models of cancer will be invaluable tools to define subcellular redox dynamics during the initiation and the progression of cancer. When used in combination with advanced imaging techniques such as two-photon live imaging through implanted optical windows in experimental animals (Weigert et al., 2013), these tools can also be used to study the dynamic response of cancer cells and/or the tumor microenvironment upon different environmental or pharmacological insults. These experimental approaches will offer the opportunity to study redox biology in live mammalian tissues and will undoubtedly open the door to novel biology. For readers interested in additional sensor variants to study redox biology in vivo, please refer to a recent review by Schwarzlander and colleagues (Schwarzlander et al., 2016).

Concluding Remarks

An emerging paradigm in the field of cancer redox biology is that ROS function as specific, intracellular secondary messengers and not binary, indiscriminate damaging molecules (Key Figure, Figure 3). This lies at the heart of much contention in the field of redox biology and accounts for conflicting clinical and preclinical studies on ROS (see Box 1). Although strategies to globally increase ROS to cytotoxic levels have shown promise in targeting cancer cells, such approaches will inevitably induce systemic toxicity much like standard chemotherapeutic regimens. To leverage cellular redox changes towards the development of a safe and effective therapeutic strategy necessitates experimental delineation of specific redox signaling pathways that are uniquely required by cancer cells to grow and to survive. In this regard, we are only beginning to appreciate the complexity of redox-signaling events. Novel molecular tools to study cysteine modifications have expanded our knowledge of proteins susceptible to cysteine oxidation and have illuminated the diverse nature of redox-mediated cell signaling events. Further elucidation of the functional consequences of individual oxidative cysteine modifications will be fundamental to advancing our understanding of complex diseases such as cancer. New molecular probes that detect redox species with temporal and spatial specificity will further shed light on the relationship between different redox couples and how they operate in different cellular compartments. Although many questions and technical challenges remain (see Outstanding Questions), the prospect of interdisciplinary collaborations between biologists, chemists and physicists towards the development of biochemical and optical platforms to define distinct redox signaling events hold promise in extinguishing the long-standing burning question in redox biology.

Key Figure, Figure 3. Redox and Cancer: Comprehensive Outlook.

In this review, we attempted to provide some insight into the diversity of redox signaling events in cancer. As cysteinyl thiol-based oxidative modifications do not exclusively mediate macromolecular damage, but also mediate intracellular signaling events, the field must advance towards investigating individual redox couples with spatial, temporal and chemical specificity. The advent of novel biochemical and biophysical tools will facilitate the elucidation of each oxidative modification in growth, viability and migration. This will move the field towards the goal of identifying cancer-specific redox vulnerabilities that can be targeted therapeutically.

Box 1. Clinician'S Corner.

Over the past decades, randomized control studies with antioxidants such as β-carotene, vitamin A and vitamin C have demonstrated no significant benefit, but rather a detrimental effect, in cancer prevention (Bjelakovic et al., 2007). Given that ROS production is a mechanism shared by most non-surgical therapeutic approaches for cancers, such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy and photodynamic therapy (Wang and Yi, 2008), clinicians should discourage supplementary antioxidant consumption by diagnosed patients based on the potential antagonistic impact of these agents to standard treatment regimens.

In contrast to studies on antioxidants, randomized control human trials with pro-oxidants for cancer therapy are still ongoing. Conceptually, a non-selective approach to globally increase oxidants in cancer as a form of therapy is expected to be suboptimal due to limited therapeutic index as a result of toxicity in sensitive tissues such as the liver and the nervous system.

However, there is promising evidence that raising ROS levels through small molecules may preferentially induce cancer cell death by disabling endogenous antioxidants (Chio et al., 2016; Glasauer et al., 2014; Raj et al., 2011; Shaw et al., 2011). High intravenous doses of the antioxidant vitamin C have also been shown to paradoxically function as pro-oxidant in certain tumors due to the local oxidation and conversion of ascorbate acid to dehydroascorbate, which then readily enters cells via the glucose transporter Glut1 to mediate metabolic and nuclear damage in Kras and Braf mutant colon cancer cells in mice (Yun et al., 2015). Previously, elevated levels of vitamin E had also been reported to exhibit pro-oxidant activity, but its role in cancer remains quite controversial (Rietjens et al., 2002). It is speculated that the differential response of cancer cells and normal cells to these treatments reflects a redox dependency associated with the transformation process that remains to be fully understood.

Outstanding Questions.

The concept that reactive oxygen species arbitrate unique signaling events inspires the following questions, both immediate and long term in the field:

On the horizon

In addition to the amino acid cysteine, methionine is another sulfur-containing amino acid that may be susceptible to oxidative modification. However, methods to bioconjugate methionines to study its oxidative changes are largely underdeveloped. A pending question is whether methionine oxidation mediates redox signaling? An innovative approach designed by Christopher Chang's team at UC Berkeley may shed light on this topic (Lin et al., 2017) and expand the scope of redox-dependent signaling mechanisms in the cell.

While this review focuses extensively on reactive oxygen species, reactive nitrogen species can also signal through S-nitrosation of cysteine residues (please refer to (Smith and Marletta, 2012) for an in depth discussion of this topic). While the soluble isoform of guanylate cyclase (sGC) is believed to be the primary effector of nitric oxide (NO) (Denninger and Marletta, 1999), a pending question is whether NO signaling involves protein targets other than sGC? If so, what are these targets and how is specificity of NO signaling conferred?

Given the ability of redox sensitive probes to reflect cellular redox changes, is it possible to marry this with intra-vital imaging and super resolution microscopy to monitor subcellular redox dynamics in real time? Obvious technical hurdles will involve the development of surgical procedures to allow exposure and proper positioning of the tissue of interest, as well as overcoming the nuance of endogenous tissue auto-fluorescence through the development of redox sensitive far-red wavelength probes. The possibility of coupling these tools with magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (Keshari et al., 2011) for in vivo measurements of redox alterations will also be of great interest.

In addition to monitoring H2O2 and glutathione redox systems, can we develop similar redox sensitive probes to assess other central redox couples such as NADPH/NADP, Thioredoxin systems or reactive nitrogen species?

Vitamin C is synthesized by a majority of vertebrate and invertebrate species including mice. Humans and other anthropoid primates, however, have lost the ability to synthesize vitamin C, due to mutations in the L-gulono-g-lactone (Gulo) gene, which codes for the enzyme responsible for catalyzing the last step of vitamin C biosynthesis. Does this difference between humans and experimental animals contribute to some of the disparities regarding the role of ROS in tumorigenesis? The Gulo knockout mouse should be evaluated in different murine experimental models of tumorigenesis to test this possibility.

The outlook

How do ROS and/or RNS initiate cell signaling? What are the dynamics of each event and how do they correlate with oncogenic insults in cancer cells?

How is specificity achieved in ROS/RNS signaling? What determines the reactivity of independent cysteine and/or methionine residues towards reactive species? Is specificity mediated through elevated local concentrations of unique reactive species or through intermediate sensors that pass on the oxidation state to target proteins through thiol-disulfide exchange?

What determines whether ROS/RNS act as deleterious oxidants versus signaling molecules? Is it a quantitative or qualitative difference of reactive species?

How do ROS/RNS mediated signaling events contribute to the process of tumorigenesis? Can these events be leveraged therapeutically?

Trends Box.

Dietary antioxidants are not prophylactic against cancer but rather increase the incidence of primary tumor formation and metastasis in experimental animal models.

Intravenous administration of high dose vitamin C worked as a pro-oxidant to suppress tumor formation in murine xenograft models of colon cancer.

Nrf2-dependent regulation of redox switches in the protein synthesis machinery promotes human and murine pancreatic tumor maintenance.

Many reactive oxygen species do not function as non-specific damaging agents in the cell, but rather, as secondary messengers with specific signaling outcomes.

Biochemical platforms to identify redox-sensitive cysteine residues are required to decipher the functional consequences of specific redox signaling events in cancer cells.

Redox-sensitive probes targeted to different cellular compartments will revolutionize our understanding of in vivo redox signaling in both time and space.

Acknowledgments

D.A.T. is a distinguished scholar of the Lustgarten Foundation and Director of the Lustgarten Foundation-designated Laboratory of Pancreatic Cancer Research. D.A.T. is also supported by the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Association, the NIH (5P30CA45508-26, 5P50CA101955-07, 1U10CA180944-03, 5U01CA168409-5, 1R01CA190092-03 and 1R01CA188134-01A1), the V Foundation, and the Thompson Family Foundation. In addition, we are grateful for support from the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation (Shirley Stein fellow, DRG-2165-13) and Human Frontier Science Program (LT000190/2013) for I.I.C.C.

Glossary

- Oxidative stress

imbalance between the production of free radicals and the ability of the cell to counteract their harmful effects (neutralization via antioxidants)

- NADPH oxidase complex

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase is a membrane bound enzyme complex that includes a cluster of proteins that donate an electron from NADPH to molecular oxygen to produce superoxide. Isoforms are designated NOX1, 2, 3 and 4. These proteins initiate a respiratory burst that constitutes a key step in immune defense against bacterial and fungal pathogens

- Metal catalysts

Transition metals and their compounds have electronic configurations enabling them to temporarily exchange electrons with reacting species. Examples include iron, titanium, vanadium, nickel, platinum and palladium. (Copper, Manganese, Zinc, Cobalt also in biology)

- Fenton chemical reaction

Metal catalyzed free radical chain reactions that are initiated by the byproducts of aerobic respiration such as hydrogen peroxide. Hydrogen peroxide can oxidize Fe2+ to produce hydroxide and the highly reactive hydroxyl radical

- Peroxiredoxins

A ubiquitous and highly conserved family of antioxidant enzymes that reduce peroxides, with a conserved cysteine residue serving as the site of oxidation by peroxides. Recycled by thioredoxin/Thioredoxin reductase

- Glutathione peroxidase

family of enzymes with peroxidase activity that reduce lipid hydroperoxides to their corresponding alcohols and free hydrogen peroxide to water

- Catalase

Enzyme found in nearly all living organisms exposed to oxygen. It catalyzes the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide to water and oxygen, and is spatially segregated in peroxisomes

- Thioredoxins

class of antioxidant proteins facilitating the reduction of other proteins by cysteine thiol-disulfide exchange

- Sulfiredoxin

Oxidoreductase enzyme that catalyzes the reactivation of the sulfinic acid forms of peroxiredoxins

- Glutathione

tri-peptide composed of cysteine, glutamic acid and glycine; functions as the major antioxidant in plants, animals, fungi, and some bacteria and archaea

- Glucose 6 phosphate dehydrogenase

Cytosolic enzyme catalyzing the oxidation of glucose 6 phosphate and the reduction of NADP+ to NADPH in the pentose phosphate pathway

- Pentose Phosphate Pathway

metabolic pathway that generates NADPH, 5-carbon sugars and ribose-5-phosphate, a precursor for nucleotide synthesis

- IDH1,2

Isocitrate dehydrogenase—enzyme that catalyzes the oxidative decarboxylation of isocitrate, producing alpha-ketoglutarate and carbon dioxide and NADPH. The isoform IDH1 is cytosolic whereas the isoform IDH2 is expressed in the mitochondria

- ME1,2,3

enzyme that catalyzes the oxidative decarboxylation of malate to pyruvate. In this process, malic enzymes reduce the dinucleotide cofactors NAD+/NADP+ to NADH/NADPH. The isoform ME1 is cytosolic, whereas ME2 and 3 are mitochondrial

- One-carbon metabolism

group of anabolic biochemical reactions (the folate cycle and the methionine cycle) during which one-carbon groups are transferred and certain amino acids and nucleotides are produced

- TIGAR

TP53-inducible glycolysis and apoptosis regulator, or fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase—enzyme that lower fructose-2,6-bisphosphate levels, resulting in inhibition of glycolysis, activation of the PPP, and decreased intracellular reactive oxygen species levels

- Mouse models of oncogenic Kras and Braf

Genetically engineered mouse models expressing endogenous oncogenic alleles of KrasG12D or BrafV600E, respectively

- NAC

N-acetylcysteine—prodrug for L-cysteine, one of the precursors of glutathione

- Trolox

6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid)—a water-soluble analog of vitamin E

- Cell basement membrane

Basal lamina—separates the epithelium from the stroma of any given tissue. Functions to provide structural support, compartmentalize tissues and regulates cell behavior

- FOXO

Class O of the forkhead box of transcription factors with important roles in metabolism, proliferation, stress response and apoptosis. Activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway leads to phosphorylation of FOXOs to regulate FOXO nuclear localization or degradation

- BRCA1

Breast cancer 1—E3 ubiquitin ligase that participates in mRNA transcription, repair of double-strand DNA breaks, and homologous recombination. Mutations of this gene account for approximately 40% of inherited breast cancers and more than 80% of inherited breast and ovarian cancers

- Anchorage independent growth

A hallmark of cancer cells that enables them to survive detachment from neighboring cells and continue proliferating. This property allows tumor cells to invade adjacent tissues and to disseminate through the body, giving rise to metastasis

- Growth factor independent growth

A property of tumor cells to proliferate in the absence of exogenous ligands of growth factor receptors

- Mitochondrial Complexes I-IV

The electron transport chain of the mitochondria is organized into 4 complexes, each of which containing several electron carriers. Electrons are removed from the reduced carrier NADH and transferred to oxygen to yield water. Complex I is also known as the NADH-coenzyme Q reductase or NADH dehydrogenase. Complex II is also known as succinate coenzyme Q reductase or succinate dehydrogenase. Complex III is known as coenzyme Q reductase. Complex IV is known as cytochrome c reductase

- MitoTEMPO

commercially available antioxidant targeted specifically to the mitochondria to scavenge mitochondrial superoxides. MitoTEMPO is a combination of the antioxidant piperidine nitroxide TEMPO with the lipophilic cation triphenylphosphonium, giving MitoTEMPO the ability to pass through lipid bilayers and accumulate in the mitochondria

- Mitochondrial transcription factor A

enzyme that is essential for mitochondrial DNA transcription and regulation of mitochondrial DNA copy number

- System Xc−

amino acid antiporter that mediates the exchange of extracellular L-cysteine and intracellular L-glutamate across cellular plasma membranes

- Ferroptosis

form of programmed cell death dependent on iron and characterized by the accumulation of lipid peroxides. It is initiated by the failure of glutathione-dependent antioxidant defenses, which can be prevented by lipophilic antioxidants and iron chelators

- Piperlongumine

atural product constituent of the fruit of Piper longum, a pepper plant found in southern India and southeast Asia. It is believed to exhibit inhibitory effect over glutathione S-transferase P, a member of a family of enzymes catalyzes the conjugation of hydrophobic and electrophilic compounds with reduced glutathione

- Necrosis

form of unprogrammed cell death involving the loss of cell membrane integrity and an uncontrolled release of products into the extracellular space

- Aquaporins

A family of integral membrane proteins that form pores in the plasma membrane and facilitate the transport of water

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.The effect of vitamin E and beta carotene on the incidence of lung cancer and other cancers in male smokers. The Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta Carotene Cancer Prevention Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1029–1035. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199404143301501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abramov AY, Scorziello A, Duchen MR. Three distinct mechanisms generate oxygen free radicals in neurons and contribute to cell death during anoxia and reoxygenation. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2007;27:1129–1138. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4468-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adam-Vizi V, Chinopoulos C. Bioenergetics and the formation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Trends in pharmacological sciences. 2006;27:639–645. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albrecht SC, Barata AG, Grosshans J, Teleman AA, Dick TP. In vivo mapping of hydrogen peroxide and oxidized glutathione reveals chemical and regional specificity of redox homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2011;14:819–829. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ames BN, Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM. Oxidants, antioxidants, and the degenerative diseases of aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:7915–7922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.7915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersen JK. Oxidative stress in neurodegeneration: cause or consequence? Nature medicine. 2004;(10 Suppl):S18–25. doi: 10.1038/nrn1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aruoma OI, Halliwell B, Hoey BM, Butler J. The antioxidant action of N-acetylcysteine: its reaction with hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radical, superoxide, and hypochlorous acid. Free Radic Biol Med. 1989;6:593–597. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(89)90066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bedard K, Krause KH. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiological reviews. 2007;87:245–313. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bensaad K, Tsuruta A, Selak MA, Vidal MN, Nakano K, Bartrons R, Gottlieb E, Vousden KH. TIGAR, a p53-inducible regulator of glycolysis and apoptosis. Cell. 2006;126:107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berndt C, Lillig CH, Holmgren A. Thiol-based mechanisms of the thioredoxin and glutaredoxin systems: implications for diseases in the cardiovascular system. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2007;292:H1227–1236. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01162.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bienert GP, Schjoerring JK, Jahn TP. Membrane transport of hydrogen peroxide. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2006;1758:994–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biteau B, Labarre J, Toledano MB. ATP-dependent reduction of cysteine-sulphinic acid by S. cerevisiae sulphiredoxin. Nature. 2003;425:980–984. doi: 10.1038/nature02075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Gluud LL, Simonetti RG, Gluud C. Mortality in randomized trials of antioxidant supplements for primary and secondary prevention: systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama. 2007;297:842–857. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.8.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breckwoldt MO, Pfister FM, Bradley PM, Marinkovic P, Williams PR, Brill MS, Plomer B, Schmalz A, St Clair DK, Naumann R, et al. Multiparametric optical analysis of mitochondrial redox signals during neuronal physiology and pathology in vivo. Nature medicine. 2014;20:555–560. doi: 10.1038/nm.3520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brennan JP, Miller JI, Fuller W, Wait R, Begum S, Dunn MJ, Eaton P. The utility of N,N-biotinyl glutathione disulfide in the study of protein S-glutathiolation. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP. 2006;5:215–225. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500212-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brunelle JK, Bell EL, Quesada NM, Vercauteren K, Tiranti V, Zeviani M, Scarpulla RC, Chandel NS. Oxygen sensing requires mitochondrial ROS but not oxidative phosphorylation. Cell Metab. 2005;1:409–414. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Budanov AV, Sablina AA, Feinstein E, Koonin EV, Chumakov PM. Regeneration of peroxiredoxins by p53-regulated sestrins, homologs of bacterial AhpD. Science. 2004;304:596–600. doi: 10.1126/science.1095569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cairns RA, Harris IS, Mak TW. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:85–95. doi: 10.1038/nrc2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cameron E, Pauling L. Supplemental ascorbate in the supportive treatment of cancer: Prolongation of survival times in terminal human cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976;73:3685–3689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.10.3685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cameron E, Pauling L. Supplemental ascorbate in the supportive treatment of cancer: reevaluation of prolongation of survival times in terminal human cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978;75:4538–4542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.9.4538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cantrell MA, Kuo CJ. Organoid modeling for cancer precision medicine. Genome medicine. 2015;7:32. doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0158-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cao L, Xu X, Cao LL, Wang RH, Coumoul X, Kim SS, Deng CX. Absence of full-length Brca1 sensitizes mice to oxidative stress and carcinogen-induced tumorigenesis in the esophagus and forestomach. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1401–1407. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chandel NS, Tuveson DA. The promise and perils of antioxidants for cancer patients. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:177–178. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1405701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang TS, Jeong W, Woo HA, Lee SM, Park S, Rhee SG. Characterization of mammalian sulfiredoxin and its reactivation of hyperoxidized peroxiredoxin through reduction of cysteine sulfinic acid in the active site to cysteine. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:50994–51001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409482200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen EI, Hewel J, Krueger JS, Tiraby C, Weber MR, Kralli A, Becker K, Yates JR, 3rd, Felding-Habermann B. Adaptation of energy metabolism in breast cancer brain metastases. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1472–1486. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen RS, Song YM, Zhou ZY, Tong T, Li Y, Fu M, Guo XL, Dong LJ, He X, Qiao HX, et al. Disruption of xCT inhibits cancer cell metastasis via the caveolin-1/beta-catenin pathway. Oncogene. 2009a;28:599–609. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Y, Azad MB, Gibson SB. Superoxide is the major reactive oxygen species regulating autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2009b;16:1040–1052. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]