Abstract

Background

Postpartum depression (PPD) can result in negative personal and child developmental outcomes. Only a few large population based studies of PPD have used clinical diagnoses of depression and no study has examined how a maternal depression history interacts with known risk factors. The objective of the study was to examine the impact of a depression history on PPD and pre- and perinatal risk factors.

Method

Nationwide prospective cohort study of all women with live singleton births in Sweden from 1997 through 2008. Relative risk of clinical depression within the first year postpartum and two-sided 95% confidence intervals.

Results

The relative risk of PPD in women with a history of depression was estimated at 21.03 (confidence interval: 19.72–22.42), compared to those without. Among all women, PPD risk increased with advanced age (1.25[1.13–1.37]) and with gestational diabetes (1.70[1.36–2.13]). Among women with a history of depression, pre-gestational diabetes (1.49[1.01–2.21]) and mild preterm delivery also increased risk (1.20[1.06–1.36]). Among women with no depression history, young age (2.14 [1.79–2.57]), those undergoing instrument assisted (1.23[1.09–1.38]) or cesarean (1.64[1.07–2.50]) delivery and moderate preterm delivery increased risk (1.36[1.05–1.75]). Rates of PPD decreased considerably after the first postpartum month (relative risk = 0.27).

Conclusion

In the largest population based study to date, the risk of PPD was more than 20 times higher for women with a depression history, compared to women without. Gestational diabetes was independently associated with a modestly increased PPD risk. Maternal depression history also had a modifying effect on pre- and perinatal PPD risk factors.

INTRODUCTION

Postpartum depression (PPD) is one of the most common non-obstetric complications associated with childbearing.1 PPD also constitutes a serious threat to the infant’s well-being as the period immediately surrounding birth is a critical window for many infant developmental events.2 Many reports have suggested that a history of depression is associated with increased PPD risk.3–5 Additional factors associated with PPD include age and other demographic characteristics,3 pregnancy complications,5 and obstetric factors.5

Research exploring risk factors associated with PPD has generally included important methodological limitations. First, the vast majority of studies have relied on clinical rather than epidemiological samples. Epidemiological samples are population-based, whereas clinical samples from care-based clinics, referral centers, and inpatient samples involve patient series, which may not represent the entire population of women with PPD.1 Second, past studies have tended to rely on PPD symptomatology rather than clinical depression diagnoses.6 Symptom based PPD inventories7 have a tendency to overestimate prevalence especially given the overlap between surveyed symptoms and common maternal discomforts of pregnancy and the postpartum.1,6 Third, while a history of depression is a strong predictor of depressive disorders throughout the lifespan, and could be an important predictor of PPD, studies to date have predominantly relied on retrospective self-report methods to determine psychiatric history.1–5 Such methods are prone to recall bias, experimenter bias, and most importantly lack clinical specificity, which may lead to further misclassification and poor estimation.1,6

This population-based, nationally inclusive, study therefore aimed to address each of these limitations by determining the extent to which a history of depression contributes to the risk of clinically recognized PPD and determining the degree to which a history of depression modifies the association between maternal obstetric and perinatal conditions and PPD. Using data on more than 700,000 deliveries in Sweden between 1997–2008, this is the largest study to date to characterize unipolar depression in the postpartum period in relation to a maternal depression history. We identified all recorded cases of PPD using national health registers with high reliability for mental health diagnoses8 and determined the clinical history of depression in all participants. We describe patterns of PPD in relation to depression history and previously identified demographic and behavioral risk factors.9 Finally, we adjusted for important confounders and multiple demographic characteristics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

Using the nationwide Swedish Medical Birth Register, which includes information on all births in Sweden, we identified a cohort comprising all Swedish born women who delivered a live singleton infant between January 1, 1997 and December 31, 2008. To avoid problems with correlated data, we included only information on the first childbirth during the study period for each woman. Since Sweden has a publically financed health system with universal access, the Medical Birth Register covers virtually all births in Sweden. The study protocol was approved by Icahn Medical School at Mount Sinai’s Program for the Protection of Human Subjects, The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare and The Ethical Review Board at Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm.

Outcomes

Since 1973, the nationwide Swedish National Patient Register has been prospectively capturing admission dates and clinical diagnoses for virtually all psychiatric hospitalizations. Since 2000, hospital outpatient care has been included in the registry as well. Diagnostic information is based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes. Dates of inclusion were selected to conform to the Swedish health system’s implementation of the ICD-10th Revision (ICD-10) in 1997. Data linkage between the Medical Birth Register and the Swedish National Patient Register was accomplished using the unique national identification number assigned to Swedish residents.10

For PPD we included diagnoses of postpartum depression, as well as major depressive disorder (single or recurrent), unspecified episodic mood disorder, or depressive disorder that occurred within the first year postpartum (Table 1). Contemporary diagnostic nosology characterizes PPD as a specifier of a major depressive disorder (unipolar) with an onset of symptoms within four weeks according to the American Psychiatric Association11 or six weeks according to the World Health Organization12 after delivery. Consistent with prior research9 and in agreement with the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology guidelines and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality,1 we defined PPD as a depression diagnosis within 12 months following the date of delivery. The additional diagnostic codes for unipolar depression reflect the range of classifications used by clinicians who diagnose depression. We defined lifetime depression history as a clinical diagnosis of depression anytime prior to the delivery date of the child using the same ICD-9/1012 codes (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

ICD diagnoses used to assess depression history and PPD within 12 months postpartum

| ICD system | Codes |

|---|---|

| ICD-9 | 296.20, 296.21, 296.22, 296.23, 296.3, 296.31, 296.32, 296.33, 296.34, 296.99, 301.1, 309.0, 311, 311.0, 648.40, 648.42, 648.44 |

| ICD-10 | F32, F320, F321, F322, F32.3*, F32.4, F32.8, F32.9, F33, F33.0, F33.1, F33.2, F33.3, F33.4, F33.8, F33.9, F34.0, F34.1, F34.8, F34.9, F38.0, F38.1, F38.8, F39, F53, F530, F53.1, F53.8, F53.9 |

Major depressive disorder, single episode, severe with psychotic features used only as a covariate

Covariates with high reliability and accuracy within the Swedish Medical Birth Register13 were selected based on previous PPD research9 and included history of depression (yes/no), year of delivery (1997–2002, 2003–2008), maternal age at delivery (15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, 40+), cohabitation with the father of the infant (yes/no), hypertensive diseases (no, preeclampsia, essential hypertension), diabetic diseases (no, pre-gestational type1 or type 2, gestational), prolonged labor (as defined by a documented ICD-code; yes/no), mode of delivery (vaginal non-instrumental, vaginal instrumental, emergency or elective cesarean section), gestational age (<32, 32–36, 37–41, >42 weeks), birth weight for gestational age (<3rd, 3rd to 14th, 15th to 84th, 85th to 97th, and >97th percentiles), congenital malformation (yes/no), and sphincter rupture (yes/no). Estimation of gestational age was based on early second trimester ultrasonic scan of fetal dimensions. If no early ultrasound investigation was available, information from the last menstrual period was used to calculate gestational age. Birth weight for gestational age was categorized into percentiles according to the Swedish reference curve for normal fetal growth.14 Information on delivery and gestational age is recorded at the time of delivery. Information on maternal and infant diagnoses are noted by the obstetrician and pediatrician, when the mother and infant are discharged from hospital.

Statistical Analysis

We estimated the relative risk (RR) of PPD with incidence rate ratios from Poisson regression models fitted to the data. Women were followed from the date of delivery until PPD, death, emigration or 12 months following the date of delivery, whichever came first. RRs of PPD were calculated for each of the covariates in the model. First, we calculated crude RRs by only including a categorical covariate for month since date of delivery and the covariate of interest. In adjusted models, we included the following covariates: maternal depression history, year of delivery, maternal age, cohabitation with father of the infant, hypertensive diseases, diabetic diseases, prolonged labor, mode of delivery, gestational age, birth weight for gestational age, congenital malformations, and sphincter rupture. Variables were categorized according to Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Cohort demographic and birth characteristics

| Characteristic | All Women (%) | Women With No Personal History of Depression (%) | Women With A Personal History of Depression (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Deliveries | 707,701 | 693,767 | 13,934 |

| Postpartum Depression | |||

| Year of Delivery | |||

| 1997–2002 | 398,691 (56) | 394,328 (57) | 4,363 (31) |

| 2003–2008 | 309,010 (44) | 299,439 (43) | 9,571 (69) |

| Maternal Age | |||

| 15–19 | 17,823 (2) | 17,215 (2) | 608 (5) |

| 20–24 | 113,432 (16) | 110,468 (16) | 2,964 (21) |

| 25–29 | 237,245 (34) | 233,248 (34) | 3,997 (29) |

| 30–34 | 223,132 (32) | 219,472 (32) | 3,660 (26) |

| 35–39 | 95,421 (13) | 93,316 (13) | 2,105 (15) |

| 40+ | 20,648 (3) | 20,048 (3) | 600 (4) |

| Cohabitation with Father | |||

| Yes | 665,793 (94) | 652,678 (94) | 13,115 (94) |

| No | 41,908 (6) | 41,089 (6) | 819 (6) |

| Hypertensive Disease | |||

| Normal | 681,746 (96) | 668,388 (96) | 13,358 (96) |

| Preeclampsia | 25,090 (4) | 24,549 (4) | 541 (4) |

| Essential hypertension | 865 (0) | 830 (0) | 35 (0) |

| Diabetes | |||

| None | 698,115 (99) | 684,497 (99) | 13,618 (98) |

| Pre-gestational | 6,297 (1) | 6,132 (1) | 165 (1) |

| Gestational | 3,289 (0) | 3,138 (0) | 151 (1) |

| Prolonged Labor | |||

| No | 699,734 (99) | 685,943 (99) | 13,791 (99) |

| Yes | 7,967 (1) | 7,824 (1) | 143 (1) |

| Mode of Delivery | |||

| Vaginal | 523,439 (74) | 513,715 (74) | 9,724 (70) |

| Vaginal instrument assisted | 73,262 (10) | 71,867 (10) | 1,395 (10) |

| Cesarean acute | 63,953 (9) | 62,480 (9) | 1,503 (11) |

| Cesarean elective | 47,047 (7) | 45,735 (7) | 1,312 (9) |

| Gestational Age (weeks) | |||

| <32 | 5,388 (1) | 5,218 (1) | 170 (1) |

| 32–36 | 33,094 (5) | 32,222 (5) | 872 (6) |

| 37–41 | 610,577 (86) | 598,697 (86) | 11,880 (86) |

| ≥42 | 58,642 (8) | 57,630 (8) | 1,012 (7) |

| Gestational Weight | |||

| <3rd percentile | 13,879 (2) | 13,496 (2) | 383 (3) |

| 3–14th percentile | 39,310 (6) | 38,388 (6) | 922 (7) |

| 15–84th percentile | 580,815 (82) | 569,636 (82) | 11,179 (80) |

| 85–97th percentile | 52,665 (7) | 51,649 (7) | 1,016 (7) |

| >97th percentile | 21,032 (3) | 20,598 (3) | 434 (3) |

| Congenital Malformation | |||

| No | 681,996 (96) | 668,574 (96) | 13,422 (96) |

| Yes | 25,705 (4) | 25,193 (4) | 512 (4) |

| Sphincter Rupture | |||

| No | 680,646 (96) | 667,109 (96) | 13,537 (97) |

| Yes | 27,055 (4) | 26,658 (4) | 397 (3) |

These models were repeated for women with and without a depression history. To facilitate the interpretation of the results, figures depicting rate of PPD (cases/10,000) by month were produced comparing women with and without a depression history; Using Kaplan-Meier techniques, log survival curves were calculated and plotted. Poisson regression models similar to above were fitted with the first month postpartum as a reference to calculate the RR of PPD in each month after delivery compared with the first month.

For all estimated RRs, the associated two-sided 95% Wald type confidence intervals (CI) were calculated, corresponding to a statistical test on the two-sided 5% level of significance. We tested for interaction between history of depression and each of the maternal obstetric and perinatal conditions in the two-sided 10% level of significance. Data management and all statistical models were conducted using SAS software (Poisson regression using proc glimmix) version 9.4 64-bit running Debian linux.

Sensitivity Analysis

As a check of robustness secondary to the inclusion of outpatient care, we repeated analyses for women who delivered an infant between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2008, while restricting the definition of history of depression to the period from January 1, 2003 to December 31, 2005. Because some outpatient diagnoses could have represented ongoing treatment for women previously diagnosed with depression, we restricted the definition of PPD to only include those diagnoses following hospitalization or coded in the register as an “acute visit” as opposed to “planned.” Information on when the visit was booked was not available in our data, but since “planned” visits scheduled one day in advance may include events of an “acute” nature, the RRs estimated using this restricted definition will, if anything, underestimate the true RR.

For all estimated RRs the associated two-sided 95% Wald type CIs were calculated, corresponding to a statistical test on the two-sided 5% level of significance.

RESULTS

Characteristics of study cohort

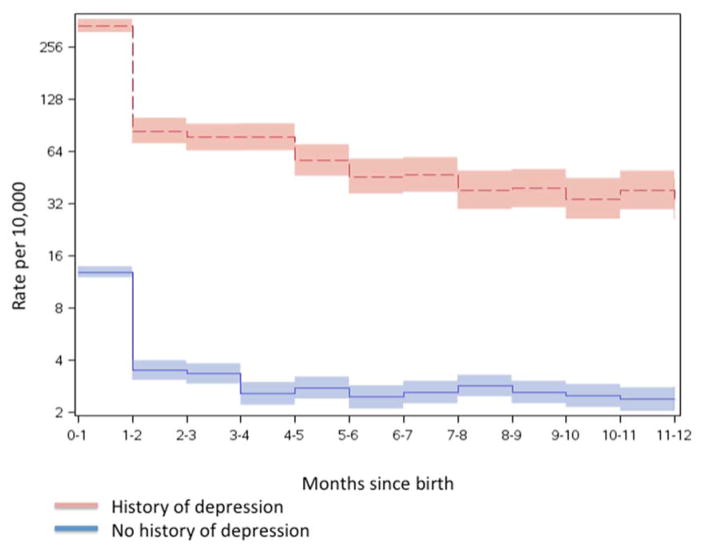

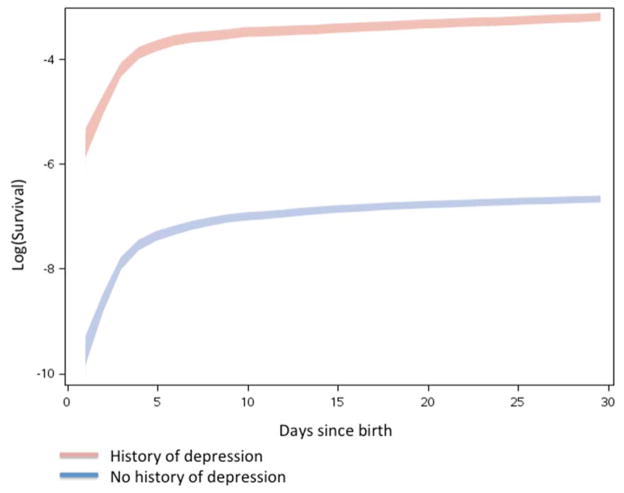

We identified at total of 707,701 unique women with a live singleton birth between 1997 and 2008. Table 2 presents the demographic and birth characteristics for the study cohort. Within the first year after delivery, there were 4,397 PPD cases (62 per 10,000; Table 2). Both among women with and without a history of depression, rates of PPD dropped dramatically one month after delivery (Figure 1), and especially after the first week (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Rates (cases/10,000 births) of PPD during the first 12 month following the date of birth of the child comparing women with (red) and without (blue) a history of depression.

Figure 2.

Survival curves for PPD during the first 30 days following the date of birth of the child comparing women with (red) and without (blue) a history of depression.

Compared with the first month after delivery, the risk of PPD rapidly decreased at the second month postpartum; RR=0.27(0.2 to 0.3) and thereafter decreased slowly for the remaining 10 postpartum months; RR=0.16(0.1 to 0.2) at month 12. As a consequence, 33% of all PPD cases were diagnosed within the first month following delivery, 50% within the first three months and 68% within the first 6 months postpartum (supplementary file, etable 1).

Maternal depression history and risk for PPD

Compared with women without a depression history, there was a statistically increased risk for PPD in women with a history of depression; RR=21.03(19.72 to 22.42).

Maternal obstetric and perinatal factors and risk for PPD

Independent of depression history, there was a statistically significant increase in PPD risk for women older than 35 years compared with women aged 25 to 29 years, RR=1.25(1.13 to 1.37), shorter gestational age, week <32 RR=1.36(1.05 to 1.75) and week 32 to 36 RR=1.20(1.06 to 1.36) compared with gestational week 37 to 41 and for women with gestational diabetes RR=1.70(1.36 to 2.13), compared with women without pre- or gestational diabetes (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Relative risk (RR) of postpartum depression (PPD) 0 to 12 months after date of delivery, for different risk factors, for all women and separately for women with and without a personal history of depression at date of delivery.

| All Women | Women With A Personal History of Depression | Women With No Personal History of Depression | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPDa Cases | Rate per 10,000 births | RRb (95% CI)c | PPDa Cases | PPDa Rate per 10,000 births | RRb (95% CI)c | PPDa Cases | PPDa Rate per 10,000 births | RRb (95% CI)c | |

| All Deliveries | 4,397 | 62 | 1,485 | 1,154 | 21.03 (19.72–22.42)** | 2,912 | 42 | 2.70 (2.60–3.00) | |

| Year of Delivery | |||||||||

| 1997–2002 | 1,164 | 29 | 249 | 595 | 915 | 23 | |||

| 2003–2008 | 3,233 | 105 | 1,236 | 1,423 | 1,997 | 67 | |||

| Maternal Age | |||||||||

| 15–19 | 184 | 104 | 1.48 (1.26–2.72)** | 45 | 781 | 0.73 (0.53–0.99)* | 139 | 81 | 2.14 (1.79–2.57)** |

| 20–24 | 785 | 70 | 1.12 (1.02–1.22)* | 253 | 905 | 0.83 (0.71–0.97)* | 532 | 48 | 1.31 (1.17–1.46)** |

| 25–29 | 1,244 | 53 | Referent | 399 | 1,078 | Referent | 845 | 36 | Referent |

| 30–34 | 1,304 | 59 | 1.11 (1.03–1.20)** | 455 | 1,367 | 1.28 (1.11–1.46)** | 849 | 39 | 1.04 (0.95–1.14) |

| 35–39 | 699 | 74 | 1.25 (1.13–1.37)** | 267 | 1,392 | 1.29 (1.10–1.50)** | 432 | 46 | 1.21 (1.08–1.36)** |

| ≥40 | 181 | 88 | 1.25 (1.07–1.47)** | 66 | 1,193 | 1.04 (0.80–1.36) | 115 | 58 | 1.38 (1.14–1.68)** |

| Cohabitation with Father | |||||||||

| Yes | 4,120 | 62 | 0.95 (0.84–1.07) | 1,397 | 1,153 | 0.99 (0.80–1.23) | 2,732 | 42 | 0.93 (0.80–1.07) |

| No | 277 | 66 | Referent | 88 | 1,162 | Referent | 189 | 46 | Referent |

| Hypertensive Disease | |||||||||

| Normal | 4,200 | 62 | Referent | 1,417 | 1,148 | Referent | 2,783 | 42 | Referent |

| Preeclampsia | 186 | 74 | 0.94 (0.81–1.10) | 61 | 1,215 | 0.87 (0.67–1.13) | 125 | 51 | 0.98 (0.82–1.19) |

| Essential hypertension | 11 | 128 | 0.92 (0.51–1.67) | 7 | 2,309 | 1.13 (0.53–2.40) | 4 | 48 | 0.70 (0.26–1.88) |

| Diabetic Disease | |||||||||

| None | 4,273 | 61 | Referent | 1,427 | 1,133 | Referent | 2,846 | 42 | Referent |

| Pre-gestational | 78 | 125 | 1.32 (0.98–1.78) | 31 | 2,179 | 1.49 (1.01–2.21)* | 47 | 77 | 1.16 (0.73–1.83) |

| Gestational | 46 | 141 | 1.70 (1.36–2.13)** | 27 | 2,036 | 1.69 (1.18–2.43)** | 19 | 61 | 1.67 (1.25–2.23)** |

| Prolonged Labor | |||||||||

| Yes | 58 | 73 | 1.08 (0.83–1.40) | 22 | 1,711 | 1.48 (0.97–2.27) | 36 | 46 | 0.92 (0.66–1.28) |

| No | 4,339 | 62 | Referent | 1,463 | 1,148 | Referent | 2,876 | 42 | Referent |

| Mode of Delivery | |||||||||

| Vaginal | 2,851 | 55 | Referent | 946 | 1,045 | Referent | 1,905 | 37 | Referent |

| Vaginal instrument assisted | 524 | 72 | 1.18 (1.08–1.30)** | 161 | 1,260 | 1.09 (0.92–1.29) | 363 | 51 | 1.23 (1.09–1.38)** |

| Caesarean Section | 1,052 | 92 | 1.37 (0.96–1.97) | 386 | 1,466 | 0.87 (0.43–1.76) | 666 | 59 | 1.64 (1.07–2.50)* |

| Caesarean Section | |||||||||

| Acute | 564 | 89 | 0.95 (0.84–1.08) | 194 | 1,421 | 1.00 (0.87–1.14) | 370 | 59 | 0.99 (0.84–1.16) |

| Elective | 458 | 98 | Referent | 184 | 1,566 | Referent | 274 | 60 | Referent |

| Gestational Age (weeks) | |||||||||

| Pregnancy Length: <32 | 65 | 122 | 1.36 (1.05–1.75)* | 22 | 1,425 | 1.12 (0.73–1.74) | 43 | 83 | 1.53 (1.12–2.10)** |

| Pregnancy Length: 32–36 | 290 | 88 | 1.20 (1.06–1.36)** | 131 | 1,690 | 1.41 (1.18–1.70)** | 159 | 50 | 1.07 (0.91–1.26) |

| Pregnancy Length: 37–41 | 3,725 | 61 | Referent | 1,244 | 1,132 | Referent | 2,481 | 42 | Referent |

| Pregnancy Length: ≥42 | 317 | 54 | 0.88 (0.78–0.99)* | 88 | 924 | 0.81 (0.65–1.00) | 229 | 40 | 0.91 (0.79–1.04) |

| Gestational Birth Weight | |||||||||

| <3rd percentile | 121 | 88 | 0.95 (0.77–1.18) | 48 | 1,382 | 0.99 (0.71–1.40) | 73 | 54 | 0.93 (0.71–1.22) |

| 3–14th percentile | 310 | 79 | 0.87 (0.77–0.98) | 113 | 1,344 | 0.86 (0.71–1.05) | 197 | 51 | 0.88 (0.76–1.01) |

| 15–84th percentile | 3,514 | 61 | Referent | 1,160 | 1,121 | Referent | 2,354 | 41 | Referent |

| 85–97th percentile | 311 | 59 | 0.87 (0.74–1.02) | 121 | 1,300 | 1.00 (0.77–1.29) | 190 | 37 | 0.82 (0.67–1.00)* |

| >97th percentile | 141 | 67 | 0.91 (0.74–1.11) | 43 | 1,069 | 0.76 (0.53–1.08) | 98 | 48 | 1.02 (0.79–1.30) |

| Congenital Malformation | |||||||||

| Yes | 166 | 65 | 0.95 (0.84–1.07) | 57 | 1,218 | 0.93 (0.71–1.22) | 109 | 43 | 0.95 (0.78–1.15) |

| No | 4,231 | 62 | Referent | 1,428 | 1,151 | Referent | 2,803 | 42 | Referent |

| Sphincter Rupture | |||||||||

| Yes | 178 | 62 | 1.14 (0.98–1.33) | 41 | 1,111 | 0.93 (0.68–1.28) | 137 | 52 | 1.22 (1.03–1.46)* |

| No | 4,219 | 66 | Referent | 1,444 | 1,155 | Referent | 2,775 | 42 | Referent |

Footnote:

p <.05;

p <.01;

Postpartum depression (PPD),

Relative risk of PPD (RR),

Two-sided 95% confidence interval (95% CI)

Modifying effect of maternal depression history on maternal obstetric and perinatal factors and risk for PPD

Depression history had a modifying effect on the risk for PPD associated with maternal age, mode of delivery, and presence of diabetic disease.

For women with a depression history, there was a statically significant lower risk for younger mothers, aged 15 to 19 and 20 to 24, but a statistically significant higher risk for mothers 30 to 34 and 35 to 39 years of age compared with mothers aged 25 to 29. There was also a statistically significant increase in PPD risk for women with pre-gestational diabetes compared with women without pre- or gestational diabetes, RR=1.49(1.01 to 2.21) in those women with a depression history.

For women without a depression history there was a statistically significant increase in PPD risk in younger mothers (aged 15 to 19 and 20 to 24 years) and in older mothers (aged 35 to 39 years and >40 years). Women without a depression history also had a statistically significant increased risk for PPD associated with mode of delivery; vaginal instrumental RR=1.23(1.09 to 1.38) and CS RR=1.64(1.07 to 2.50) compared with vaginal delivery. Tests of interactions between history of depression and each of the factors above revealed statistically significant interactions on the nominal 2-sided 10% level of significance for maternal age (p<0.001) and gestational age (p<0.05).

Sensitivity analyses

There was no evidence for bias due to time trends in diagnosed PPD, or changes in administrative reporting (supplementary file, eTables 2–7). Sensitivity analyses for visits registered as “acute” as opposed to “planned” also showed similar results, except that there was no longer an association between sphincter rupture and PPD in women without a history of depression (supplementary file, eTables 8–13). In this restricted sample of birth, only maternal age showed a statistically significant interaction with history of depression.

DISCUSSION

In the largest longitudinal population based PPD study to date with prospective follow-up using clinically ascertained rates of depression, we found a highly increased risk for PPD in women with a history of depression compared to women without a history of depression. Second, we clarify previously identified maternal perinatal and obstetric risk factors for PPD. Finally, for the first time, we show how maternal and obstetric risk factors for PPD may differ between new mothers with and without a history of depression.

The observed rate of PPD in the Swedish population (62/10,000) was within the range suggested by the few other population-based reports that also used the more stringent criteria of clinical diagnoses: United States9 (31/10,000), Denmark15 (51/10,000), and Finland16 (28/10,000). Notably, depressive disorders after pregnancy exist along a continuum of severity rather than as an all or none phenomenon1 and the vast majority of studies exploring PPD risk have relied on symptom based measures that are prone to producing higher prevalence estimates.1,6 This is in part due to their inability to differentiate between clinically significant symptoms of depression and commonly reported, non-pathological, postpartum discomforts including sleep disturbance, changes in appetite, decreased energy, and concentration difficulties.

Our findings show that a history of depression represents more than a 20-fold increased risk for PPD. Though the association between a history of depression and the risk for PPD has been recognized,1,3,5 the extent to which a history of depression confers and may modify PPD risk has not been rigorously examined nor quantified. Several other maternal characteristics and medical conditions have also been previously shown to be associated with PPD including maternal age,3 pregnancy complications,5 and obstetric factors.5 Our findings add to this body of work and for the first time detail the risk for PPD in relation to depression history potentially helping to clarify previously indeterminate results.

Maternal Age and PPD

Some studies have shown that adolescents are at higher risk for PPD17 while others show no increased risk for adolescents, but rather a five-fold increased risk for those over the age of 30.18 Our findings show that PPD risk is associated with maternal age, but also how this risk is modified by depression history. That is, among women with no history of depression, young mothers had an increased risk for PPD compared with mothers aged 25 to 29 years. Pregnancy during adolescence is well understood to pose additional challenges for new mothers as they seek to navigate both their own development and the responsibilities of caring for a newborn. However, because of their youth and the nature of depression as a disorder with increasing likelihood across the lifespan, younger women simply due to their age would presumably be less likely than their more mature counterparts to have received a diagnosis of depression prior to pregnancy. It is therefore intuitive that a larger proportion of younger mothers who experience PPD, would not only be free of a depression history, but might also receive their first diagnosis in the postpartum period. Conversely, among those mothers with a depression history, our findings showed an increased risk with advanced maternal age (>35 years) compared with mothers aged 25 to 29 years. Indeed, in those women with a depression history, trends in PPD risk in the later age ranges of 30–34 years and 35–39 years all conferred a significantly greater likelihood. Notably, this observation did not hold for women >40+ years of age and may be due to the comparatively lower number of women in this particular cohort.

Diabetes and PPD

Prior studies examining the relationship between diabetes and PPD have been indeterminate.19 Complicating the matter is that the differences between gestational and pre-gestational diabetes are not fully understood,20 and because gestational diabetes represents any degree of glucose intolerance identified during pregnancy, even if it existed before pregnancy (i.e., pre-gestational) and regardless of whether it persists or emerges after pregnancy, research exploring this relationship has generally suffered from incomplete diagnostic resolution. Not yet demonstrated before, our findings show that for those with a history of depression, diabetes adds an additional 1.5 fold increased risk for PPD. Further, our study shines new light on the relationship between diabetes and depression by showing that gestational diabetes was strongly associated with increased risk for PPD in women regardless of their depression history, while pre-gestational (type 1 or type 2) diabetes represented an increased risk only in those women with a history of depression. Given that pre-gestational diabetes is generally considered to be a more serious and life altering medical condition, this finding initially appears somewhat surprising. However, because diabetes and depression are highly correlated21 with bidirectional causality,22 it is possible that those with pre-gestational diabetes who have no history of depression represent a PPD resilient sub-group.23,24

Preterm Delivery

Previous studies into the association between gestational age and PPD have been inconclusive.25,26 Our results show that independent of depression history, preterm delivery was associated with an overall increased risk for PPD. A possible explanation for this finding relates to our methodology of following women for a full year after delivery,1,9 thereby potentially capturing later depression diagnoses. In line with current convention, we defined preterm delivery as a live birth that occurs before 37 weeks gestation. In an effort to potentially increase the resolution of the relationship we stratified prematurity into mild (32–36 weeks gestation) and moderate (<32 weeks gestation) categories. Further analysis revealed that women free of a depression history were at a 1.5-fold increased risk for PPD when their child was born moderately premature. While it is possible that this finding is closely associated with the separation of the mother from her newborn via admission to a prolonged intensive care stay, because women with a depression history were at a significantly increased PPD risk even with mild prematurity, it is possible that like diabetes22 the two factors share a bidirectional causal path.

Mechanistic Causes of PPD

This is the first study to clarify the role of a maternal history of depression with clinically ascertained risk factors for PPD in a nationally inclusive sample. The results of this study suggest the possibility of two major pathways into the development of PPD: one through a history of depression, and the other through specific pregnancy related risk factors. PPD in woman with a history of depression may represent the natural recurrence of depressive episodes,27 while PPD due to events surrounding pregnancy and delivery may represent a different mechanism. While the stress associated with the responsibilities of caring for a newborn represents a challenge for most, if not all, new mothers, a possible unifying biological mechanism for PPD includes abnormalities associated with the immune system.

The reproductive process is profoundly immunologic28 as well as hormonal29 and human studies have consistently demonstrated a role for inflammatory processes in the etiology of depression outside of pregnancy.30,31 Inflammatory dysregulation has also been demonstrated as a cause for preterm birth32 and adverse obstetric outcomes.33 Similarly, alterations in the immune system have been documented with aging34 as well as the pathophysiology of diabetic disease.30,35 While it remains unknown whether these systemic events share etiologic mechanisms with PPD,34 future studies should consider the possibility of neuroimmunological mechanisms of PPD along with other biological aspects of childbirth, such as fluctuations in reproductive hormone levels.34–36

Strengths and Limitations

This study was designed, in part, to directly address limitations of previous research on PPD. Strengths of this study include the use of a population-based cohort with complete national coverage ascertaining clinically significant instances of depression after childbirth. However, the results of the study should be interpreted in light of several potential limitations. Even though the Swedish registers have been repeatedly shown to have high validity with complete coverage of all psychiatric discharges10 and that the outcome of clinical depression is likely to have high specificity, there will be incomplete sensitivity if women did not seek medical care.37 It is therefore possible that the association between depression history and PPD is underestimated. However, due to Sweden’s nationwide perinatal health initiatives and universal health care provision mandating universal postpartum “in home” visits conducted by specialist clinicians, with near 100% participation,38 observed registry rates for PPD more likely represent treatment capture as opposed to merely reflecting self-initiated treatment behavior. Similarly, our method of following women for one year post-delivery circumvents the need for the depression diagnoses to be limited to the immediate postpartum or even a single practitioner visit. It should be noted that registry based clinical diagnoses do not only represent new incident cases, but also service utilization. However, a sensitivity analysis restricting PPD cases following only acute or inpatient visits revealed a comparably sized risk.

Finally, we observed an increased number of PPD cases in the later cohort years. Interestingly, this observation is consistent with a few other recent population-based studies of PPD, one from the United Kingdom4 and two others from the United States.9,.39 While we know of no study that has explored this time-trend phenomenon, possible explanations include the increased awareness of PPD as well as improved strategies aimed at identifying early maternal depression. Indeed, the importance of identifying depression after childbirth has gained considerable attention and universal postpartum screening programs have become an appealing option for many.40 Importantly, a sensitivity analysis restricting our model to the 2003–2008 cohort, in an effort to address the increase of diagnoses in the register due to the addition of outpatient data, verified our reported findings.

CONCLUSION

In the largest population based study to date, PPD risk was associated with a history of depression and with obstetric and perinatal factors. There is a highly elevated risk for PPD among women with a history of depression compared to women without a history of depression. Never shown before, some of the risks associated with obstetric and perinatal factors are modified by a history of depression, suggesting differences in the etiology of PPD between women with and without a personal history of depression.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health; Grant HD073010 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS

H Larsson has served as a speaker for Eli-Lilly and Shire and has received a research grant from Shire; all outside the submitted work.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Larsson has served as a speaker for Eli-Lilly and has received a research grant from Shire; both outside the submitted work.

Author Contributions: Dr. Silverman and Dr. Sandin had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: All authors.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Silverman, Sandin, Reichenberg, Savitz.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Sandin, Savitz

Obtained funding: Silverman.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Lichtenstein, Hultman, Cnattingius, Larsson

Study supervision: Lichtenstein, Larsson, Hultman, Reichenberg.

References

- 1.Gaynes BN, Gavin N, Meltzer-Brody S, et al. Perinatal Depression: Prevalence, Screening Accuracy, and Screening Outcomes. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Feb, 2005. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 119. (Prepared by the RTI-University of North Carolina Evidence-based Practice Center, under Contract No. 290-02-0016.) AHRQ Publication No. 05-E006-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Surkan PJ, Ettinger AK, Ahmed S, et al. Impact of maternal depressive symptoms on growth of preschool- and school-aged children. Pediatrics. 2012;130(4):847–855. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vesga-López O, Blanco C, Keyes K, et al. Psychiatric disorders in pregnant and postpartum women in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(7):805–815. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davé S, Petersen I, Sherr L, Nazareth I. Incidence of maternal and paternal depression in primary care: a cohort study using a primary care database. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(11):1038–44. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robertson E, Grace S, Wallington T, Stewart DE. Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: a synthesis of recent literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26(4):289–95. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gjerdingen DK, Yawn BP. Postpartum depression screening: importance, methods, barriers, and recommendations for practice. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20(3):280–8. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2007.03.060171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlsson AC, Wändell P, Ösby U, et al. High prevalence of diagnosis of diabetes, depression, anxiety, hypertension, asthma and COPD in the total population of Stockholm, Sweden - a challenge for public health. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):670. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Savitz D, Stein C, Yee F, et al. The epidemiology of hospitalized postpartum depression in New York State, 1995–2004. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21(6):399–406. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:450. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. Geneva: WHO; 1992. 10th Revision (ICD-10) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johansson S, Villamor E, Altman M, et al. Maternal overweight and obesity in early pregnancy and risk of infant mortality: a population based cohort study in Sweden. BMJ. 2014;349:g6572. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g6572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marsál K, Persson PH, Larsen T, et al. Intrauterine growth curves based on ultrasonically estimated foetal weights. Acta Paediatr. 1996;85:843–848. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1996.tb14164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munk-Olsen T, Laursen TM, Pedersen CB, et al. New parents and mental disorders: a population based register study. JAMA. 2006;296(21):2582-258-9. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.21.2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Räisänen S, Lehto SM, Nielsen HS, et al. Fear of childbirth predicts postpartum depression: a population-based analysis of 511 422 singleton births in Finland. BMJ Open. 2013 Nov 28;3(11):e004047. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lanzi RG, Bert SC, Jacobs BK. Depression among a sample of first-time adolescent and adult mothers. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2009;22:194–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2009.00199.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luke S, Salihu HM, Alio AP, et al. Risk factors for major antenatal depression among low-income African American women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009;18:1841–1846. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kozhimannil KB, Pereira MA, Harlow BL. Association between diabetes and perinatal depression among low-income mothers. JAMA. 2009;301(8):842–847. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fong A, Serra A, Herrero T, Pan D, et al. Pre-gestational versus gestational diabetes: a population based study on clinical and demographic differences. J Diabetes Complications. 2014;28(1):29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2013.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mezuk B, Eaton WW, Albrecht S, Golden SH. Depression and type 2 diabetes over the lifespan: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(12):2383–90. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pan A, Lucas M, Sun Q, et al. Bidirectional association between depression and type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(21):1884–91. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Santos FR, Bernardo V, Gabbay MA, et al. The impact of knowledge about diabetes, resilience and depression on glycemic control: a cross-sectional study among adolescents and young adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2013;5(1):55. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-5-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Son J, Nyklícek I, Pop VJ, et al. The effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on emotional distress, quality of life, and HbA(1c) in outpatients with diabetes (DiaMind): a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(4):823–30. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drewett R, Blair P, Emmett P, et al. Failure to thrive in the term and preterm infants of mothers depressed in the postnatal period: a population-based birth cohort study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45:359–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forman DN, Videbech P, Hedegaard M, et al. Postpartum depression: identification of women at risk. BJOG. 2000;107:1210–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb11609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Viktorin A, Meltzer-Brody S, Kuja-Halkola R, et al. Heritability of Perinatal Depression and Genetic Overlap With Nonperinatal Depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;173(2):158–165. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15010085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aagaard-Tillery KM, Silver R, Dalton J. Immunology of normal pregnancy. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;11(5):279–95. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steiner M, Dunn E, Born L. Hormones and mood: from menarche to menopause and beyond. J Affect Disord. 2003;74(1):67–83. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00432-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller AH, Maletic V, Raison CL. Inflammation and its discontents: the role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(9):732–741. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pollmächer T, Haack M, Schuld A, et al. Low levels of circulating inflammatory cytokines--do they affect human brain functions? Brain Behav Immun. 2002;16(5):525–532. doi: 10.1016/s0889-1591(02)00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Romero R, Dey SK, Fisher SJ. Preterm labor: one syndrome, many causes. Science. 2014;345(6198):760–765. doi: 10.1126/science.1251816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coussons-Read ME, Lobel M, Carey JC, et al. The occurrence of preterm delivery is linked to pregnancy-specific distress and elevated inflammatory markers across gestation. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26(4):650–659. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dantzer R, O’Connor JC, Freund GG, et al. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(1):46–56. doi: 10.1038/nrn2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Golden SH, Lazo M, Carnethon M, et al. Examining a bidirectional association between depressive symptoms and diabetes. JAMA. 2008;299(23):2751–2759. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.23.2751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bloch M, Schmidt PJ, Danaceau M, et al. Effects of gonadal steroids in women with a history of postpartum depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(6):924–930. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lecrubier Y. Widespread underrecognition and undertreatment of anxiety and mood disorders: results from 3 European studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(Suppl 2):36–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jansson A, Isacsson A, Nyberg P. Help-seeking patterns among parents with a newborn child. Public Health Nurs. 1998;15(5):319–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.1998.tb00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Do T, Hu Z, Otto J, Rohrbeck P. Depression and suicidality during the postpartum period after first time deliveries, active component service women and dependent spouses, U.S. Armed Forces, 2007–2012. MSMR. 2013;20(9):2–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Baumann LC, Davidson KW, et al. US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) Screening for Depression in Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2016;315(4):380–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]